6f6812634fad1b01e94ff24d5008eef6.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 41

Automated Reasoning Systems For first order Predicate Logic

Automated Reasoning Systems For first order Predicate Logic

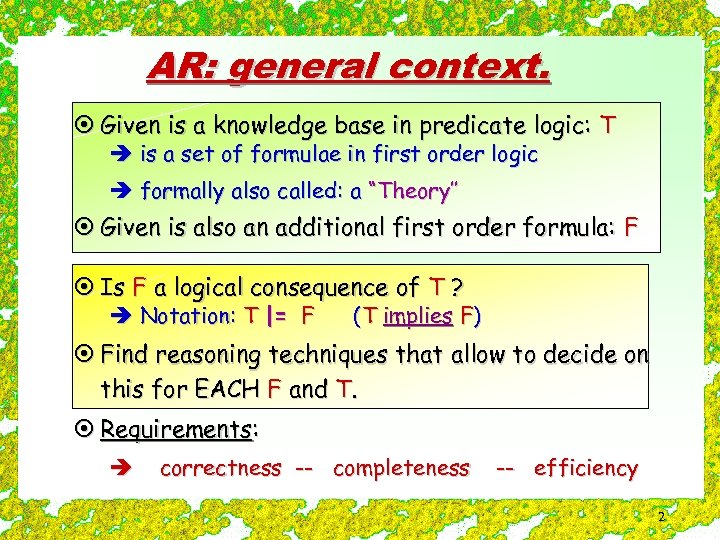

AR: general context. ¤ Given is a knowledge base in predicate logic: T è is a set of formulae in first order logic è formally also called: a “Theory’’ ¤ Given is also an additional first order formula: F ¤ Is F a logical consequence of T ? è Notation: T |= F (T implies F) ¤ Find reasoning techniques that allow to decide on this for EACH F and T. ¤ Requirements: è correctness -- completeness -- efficiency 2

AR: general context. ¤ Given is a knowledge base in predicate logic: T è is a set of formulae in first order logic è formally also called: a “Theory’’ ¤ Given is also an additional first order formula: F ¤ Is F a logical consequence of T ? è Notation: T |= F (T implies F) ¤ Find reasoning techniques that allow to decide on this for EACH F and T. ¤ Requirements: è correctness -- completeness -- efficiency 2

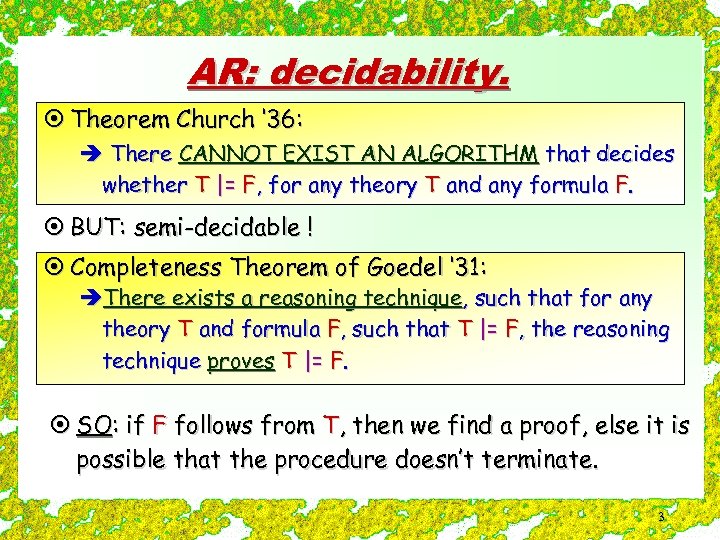

AR: decidability. ¤ Theorem Church ‘ 36: è There CANNOT EXIST AN ALGORITHM that decides whether T |= F, for any theory T and any formula F. ¤ BUT: semi-decidable ! ¤ Completeness Theorem of Goedel ‘ 31: èThere exists a reasoning technique, such that for any theory T and formula F, such that T |= F, the reasoning technique proves T |= F. ¤ SO: if F follows from T, then we find a proof, else it is possible that the procedure doesn’t terminate. 3

AR: decidability. ¤ Theorem Church ‘ 36: è There CANNOT EXIST AN ALGORITHM that decides whether T |= F, for any theory T and any formula F. ¤ BUT: semi-decidable ! ¤ Completeness Theorem of Goedel ‘ 31: èThere exists a reasoning technique, such that for any theory T and formula F, such that T |= F, the reasoning technique proves T |= F. ¤ SO: if F follows from T, then we find a proof, else it is possible that the procedure doesn’t terminate. 3

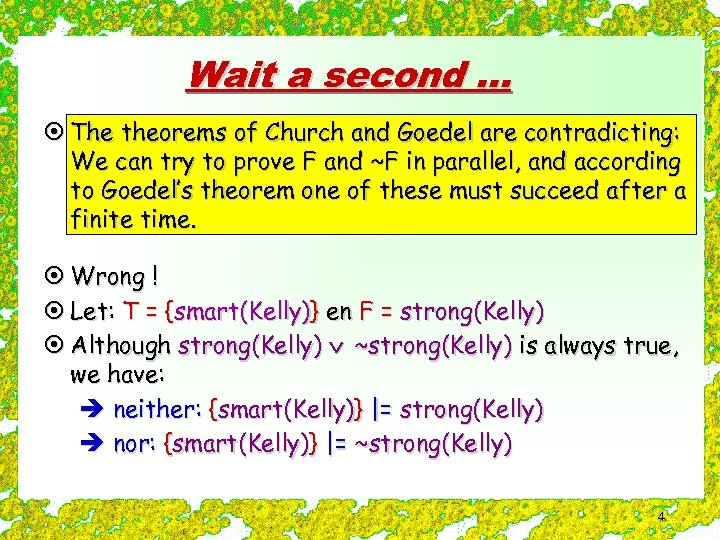

Wait a second. . . ¤ The theorems of Church and Goedel are contradicting: We can try to prove F and ~F in parallel, and according to Goedel’s theorem one of these must succeed after a finite time. ¤ Wrong ! ¤ Let: T = {smart(Kelly)} en F = strong(Kelly) ¤ Although strong(Kelly) ~strong(Kelly) is always true, we have: è neither: {smart(Kelly)} |= strong(Kelly) è nor: {smart(Kelly)} |= ~strong(Kelly) 4

Wait a second. . . ¤ The theorems of Church and Goedel are contradicting: We can try to prove F and ~F in parallel, and according to Goedel’s theorem one of these must succeed after a finite time. ¤ Wrong ! ¤ Let: T = {smart(Kelly)} en F = strong(Kelly) ¤ Although strong(Kelly) ~strong(Kelly) is always true, we have: è neither: {smart(Kelly)} |= strong(Kelly) è nor: {smart(Kelly)} |= ~strong(Kelly) 4

AR: general outline (1). ¤ First we sketch the most generally used approach for automated reasoning in first-order logic: è backward resolution ¤ The different technical components will only be explained in full detail in a second pass (outline (2)). 5

AR: general outline (1). ¤ First we sketch the most generally used approach for automated reasoning in first-order logic: è backward resolution ¤ The different technical components will only be explained in full detail in a second pass (outline (2)). 5

AR: general outline (2). ¤ We study different subsets of predicate logic: è ground Horn clause logic è Clausal logic è full predicate logic ¤ In each case we study semi-deciding procedures. ¤ Each extension requires the introduction of new techniques. 6

AR: general outline (2). ¤ We study different subsets of predicate logic: è ground Horn clause logic è Clausal logic è full predicate logic ¤ In each case we study semi-deciding procedures. ¤ Each extension requires the introduction of new techniques. 6

Backward Reasoning Resolution … in a nutshell

Backward Reasoning Resolution … in a nutshell

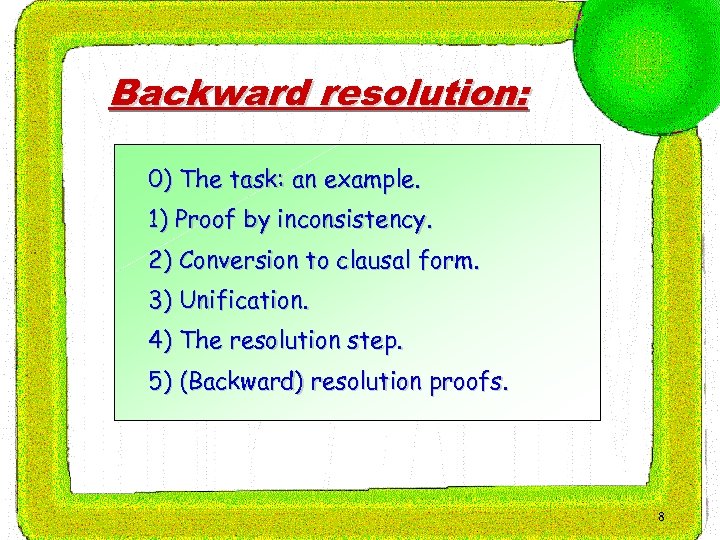

Backward resolution: 0) The task: an example. 1) Proof by inconsistency. 2) Conversion to clausal form. 3) Unification. 4) The resolution step. 5) (Backward) resolution proofs. 8

Backward resolution: 0) The task: an example. 1) Proof by inconsistency. 2) Conversion to clausal form. 3) Unification. 4) The resolution step. 5) (Backward) resolution proofs. 8

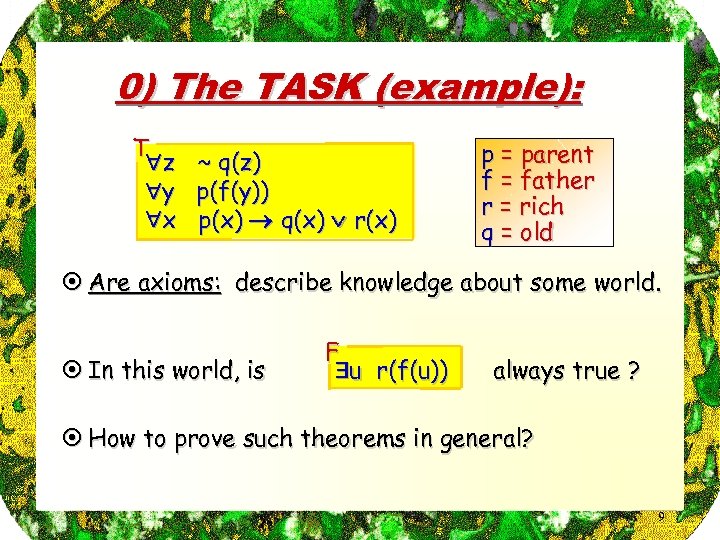

0) The TASK (example): T z y x ~ q(z) p(f(y)) p(x) q(x) r(x) p = parent f = father r = rich q = old ¤ Are axioms: describe knowledge about some world. ¤ In this world, is F u r(f(u)) always true ? ¤ How to prove such theorems in general? 9

0) The TASK (example): T z y x ~ q(z) p(f(y)) p(x) q(x) r(x) p = parent f = father r = rich q = old ¤ Are axioms: describe knowledge about some world. ¤ In this world, is F u r(f(u)) always true ? ¤ How to prove such theorems in general? 9

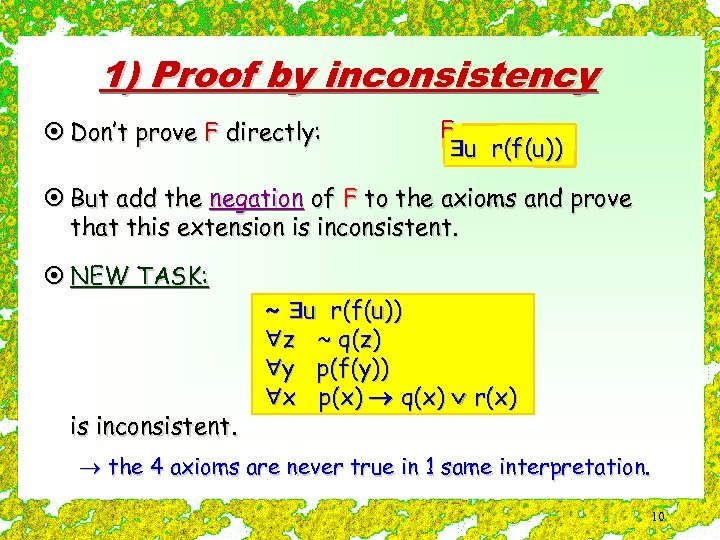

1) Proof by inconsistency ¤ Don’t prove F directly: F u r(f(u)) ¤ But add the negation of F to the axioms and prove that this extension is inconsistent. ¤ NEW TASK: is inconsistent. ~ u r(f(u)) z ~ q(z) y p(f(y)) x p(x) q(x) r(x) ® the 4 axioms are never true in 1 same interpretation. 10

1) Proof by inconsistency ¤ Don’t prove F directly: F u r(f(u)) ¤ But add the negation of F to the axioms and prove that this extension is inconsistent. ¤ NEW TASK: is inconsistent. ~ u r(f(u)) z ~ q(z) y p(f(y)) x p(x) q(x) r(x) ® the 4 axioms are never true in 1 same interpretation. 10

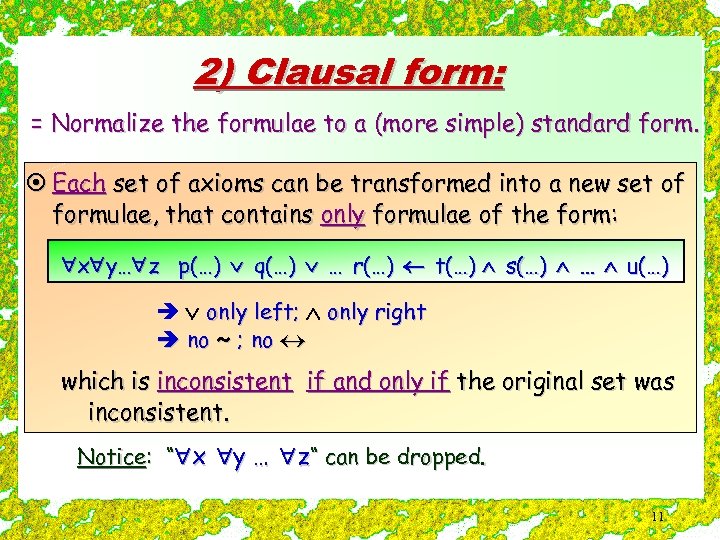

2) Clausal form: = Normalize the formulae to a (more simple) standard form. ¤ Each set of axioms can be transformed into a new set of formulae, that contains only formulae of the form: x y… z p(…) q(…) … r(…) t(…) s(…) … u(…) è only left; only right è no ~ ; no which is inconsistent if and only if the original set was inconsistent. Notice: “ x y … z“ can be dropped. 11

2) Clausal form: = Normalize the formulae to a (more simple) standard form. ¤ Each set of axioms can be transformed into a new set of formulae, that contains only formulae of the form: x y… z p(…) q(…) … r(…) t(…) s(…) … u(…) è only left; only right è no ~ ; no which is inconsistent if and only if the original set was inconsistent. Notice: “ x y … z“ can be dropped. 11

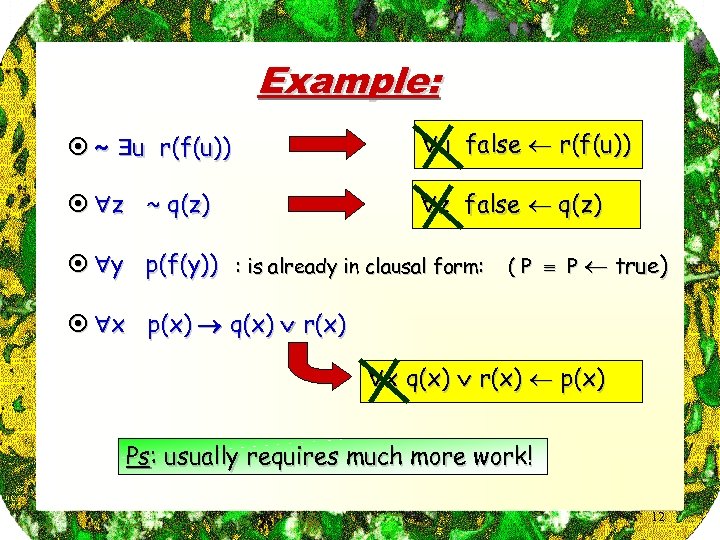

Example: ¤ ~ u r(f(u)) u false r(f(u)) ¤ z ~ q(z) z false q(z) ¤ y p(f(y)) : is already in clausal form: ( P P true) ¤ x p(x) q(x) r(x) x q(x) r(x) p(x) Ps: usually requires much more work! 12

Example: ¤ ~ u r(f(u)) u false r(f(u)) ¤ z ~ q(z) z false q(z) ¤ y p(f(y)) : is already in clausal form: ( P P true) ¤ x p(x) q(x) r(x) x q(x) r(x) p(x) Ps: usually requires much more work! 12

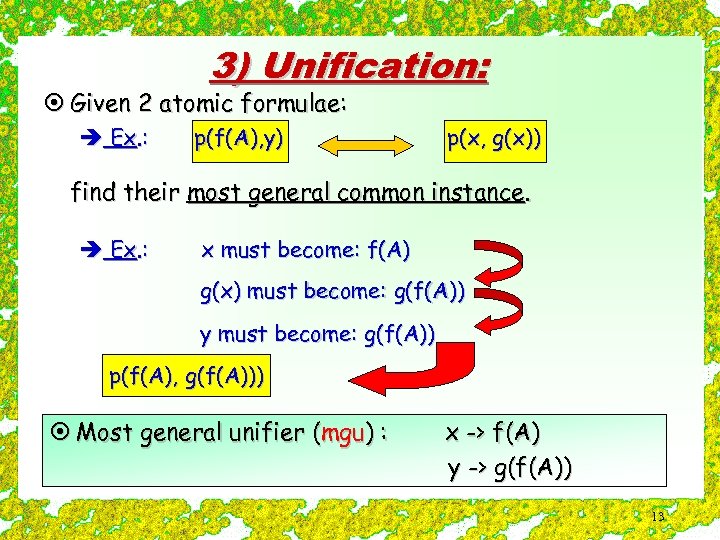

3) Unification: ¤ Given 2 atomic formulae: è Ex. : p(f(A), y) p(x, g(x)) find their most general common instance. è Ex. : x must become: f(A) g(x) must become: g(f(A)) y must become: g(f(A)) p(f(A), g(f(A))) ¤ Most general unifier (mgu) : x -> f(A) y -> g(f(A)) 13

3) Unification: ¤ Given 2 atomic formulae: è Ex. : p(f(A), y) p(x, g(x)) find their most general common instance. è Ex. : x must become: f(A) g(x) must become: g(f(A)) y must become: g(f(A)) p(f(A), g(f(A))) ¤ Most general unifier (mgu) : x -> f(A) y -> g(f(A)) 13

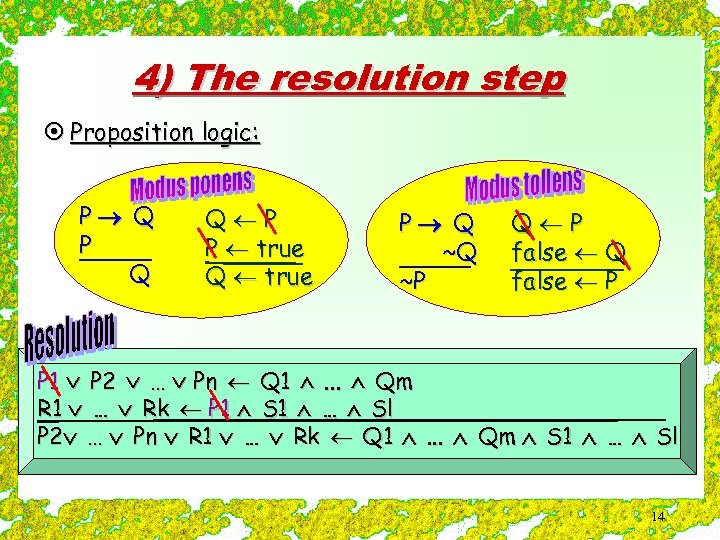

4) The resolution step ¤ Proposition logic: P Q Q P P true Q true P Q ~Q ~P Q P false Q false P P 1 P 2 … Pn Q 1 . . . Qm R 1 … Rk P 1 S 1 … Sl P 2 … Pn R 1 … Rk Q 1 . . . Qm S 1 … Sl 14

4) The resolution step ¤ Proposition logic: P Q Q P P true Q true P Q ~Q ~P Q P false Q false P P 1 P 2 … Pn Q 1 . . . Qm R 1 … Rk P 1 S 1 … Sl P 2 … Pn R 1 … Rk Q 1 . . . Qm S 1 … Sl 14

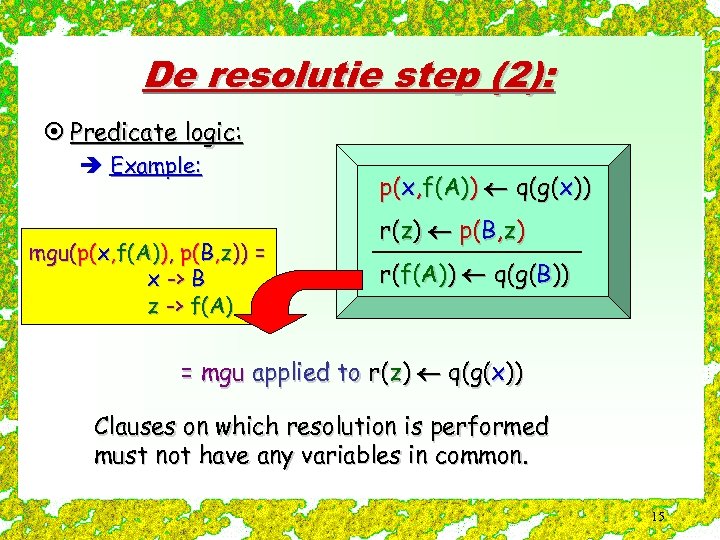

De resolutie step (2): ¤ Predicate logic: è Example: mgu(p(x, f(A)), p(B, z)) = x -> B z -> f(A) p(x, f(A)) q(g(x)) r(z) p(B, z) r(f(A)) q(g(B)) = mgu applied to r(z) q(g(x)) Clauses on which resolution is performed must not have any variables in common. 15

De resolutie step (2): ¤ Predicate logic: è Example: mgu(p(x, f(A)), p(B, z)) = x -> B z -> f(A) p(x, f(A)) q(g(x)) r(z) p(B, z) r(f(A)) q(g(B)) = mgu applied to r(z) q(g(x)) Clauses on which resolution is performed must not have any variables in common. 15

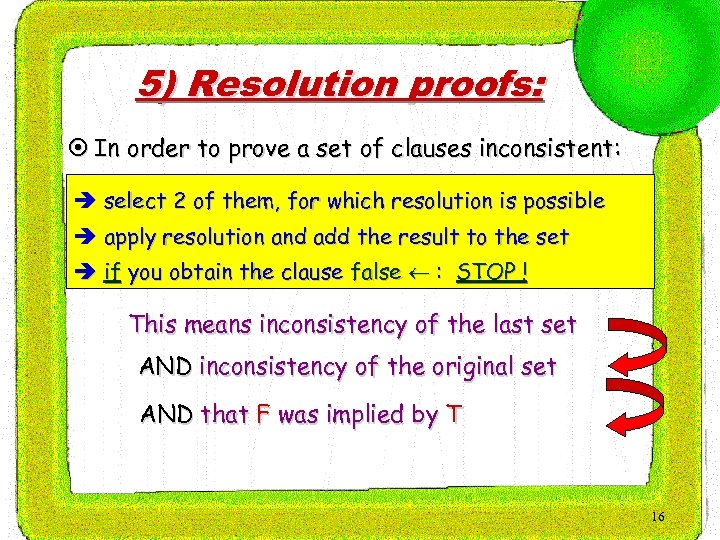

5) Resolution proofs: ¤ In order to prove a set of clauses inconsistent: è select 2 of them, for which resolution is possible è apply resolution and add the result to the set è if you obtain the clause false : STOP ! This means inconsistency of the last set AND inconsistency of the original set AND that F was implied by T 16

5) Resolution proofs: ¤ In order to prove a set of clauses inconsistent: è select 2 of them, for which resolution is possible è apply resolution and add the result to the set è if you obtain the clause false : STOP ! This means inconsistency of the last set AND inconsistency of the original set AND that F was implied by T 16

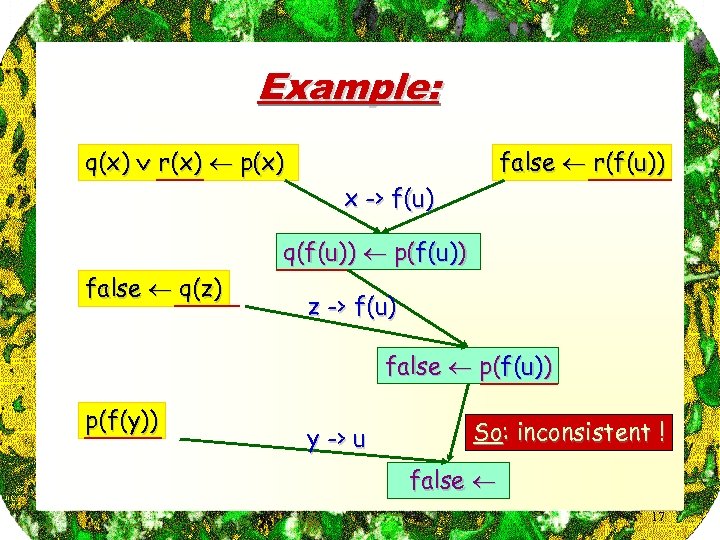

Example: q(x) r(x) p(x) false r(f(u)) x -> f(u) q(f(u)) p(f(u)) false q(z) z -> f(u) false p(f(u)) p(f(y)) y -> u So: inconsistent ! false 17

Example: q(x) r(x) p(x) false r(f(u)) x -> f(u) q(f(u)) p(f(u)) false q(z) z -> f(u) false p(f(u)) p(f(y)) y -> u So: inconsistent ! false 17

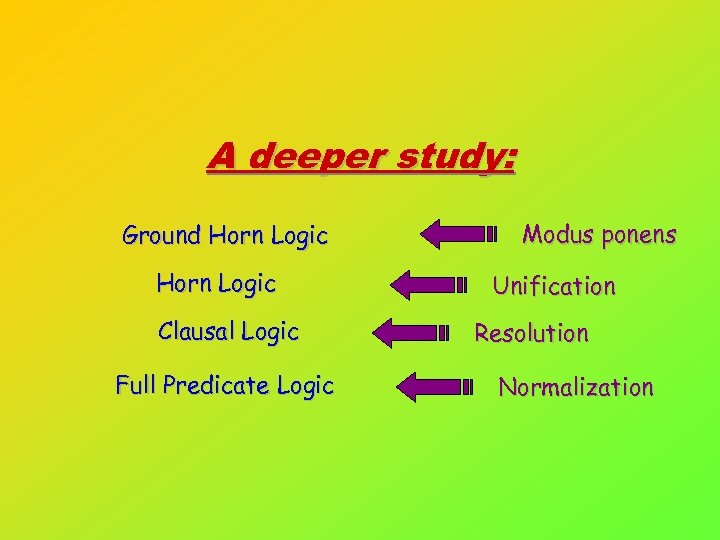

A deeper study: Ground Horn Logic Clausal Logic Full Predicate Logic Modus ponens Unification Resolution Normalization

A deeper study: Ground Horn Logic Clausal Logic Full Predicate Logic Modus ponens Unification Resolution Normalization

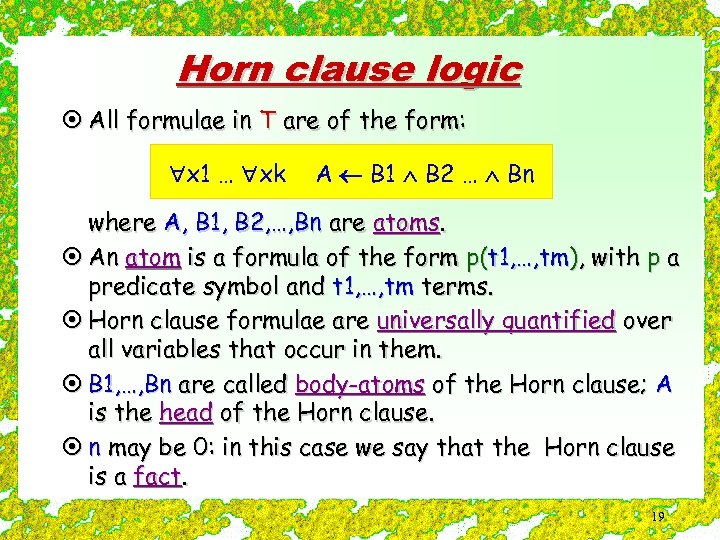

Horn clause logic ¤ All formulae in T are of the form: x 1 … xk A B 1 B 2 … Bn where A, B 1, B 2, …, Bn are atoms. ¤ An atom is a formula of the form p(t 1, …, tm), with p a predicate symbol and t 1, …, tm terms. ¤ Horn clause formulae are universally quantified over all variables that occur in them. ¤ B 1, …, Bn are called body-atoms of the Horn clause; A is the head of the Horn clause. ¤ n may be 0: in this case we say that the Horn clause is a fact. 19

Horn clause logic ¤ All formulae in T are of the form: x 1 … xk A B 1 B 2 … Bn where A, B 1, B 2, …, Bn are atoms. ¤ An atom is a formula of the form p(t 1, …, tm), with p a predicate symbol and t 1, …, tm terms. ¤ Horn clause formulae are universally quantified over all variables that occur in them. ¤ B 1, …, Bn are called body-atoms of the Horn clause; A is the head of the Horn clause. ¤ n may be 0: in this case we say that the Horn clause is a fact. 19

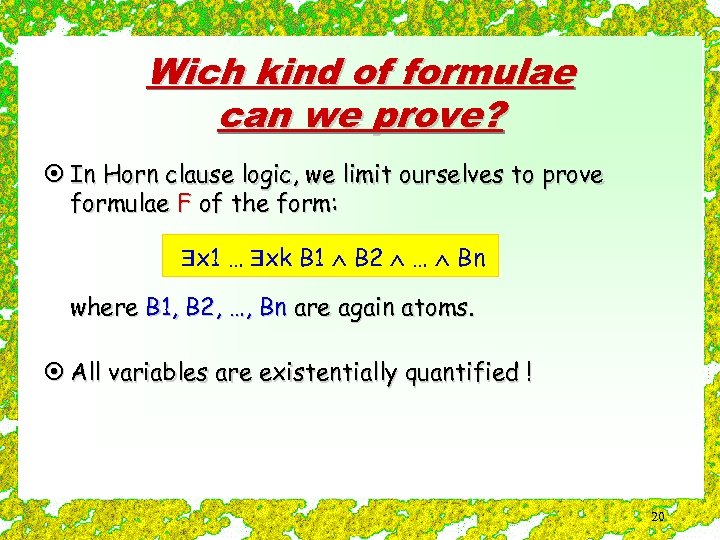

Wich kind of formulae can we prove? ¤ In Horn clause logic, we limit ourselves to prove formulae F of the form: x 1 … xk B 1 B 2 … Bn where B 1, B 2, …, Bn are again atoms. ¤ All variables are existentially quantified ! 20

Wich kind of formulae can we prove? ¤ In Horn clause logic, we limit ourselves to prove formulae F of the form: x 1 … xk B 1 B 2 … Bn where B 1, B 2, …, Bn are again atoms. ¤ All variables are existentially quantified ! 20

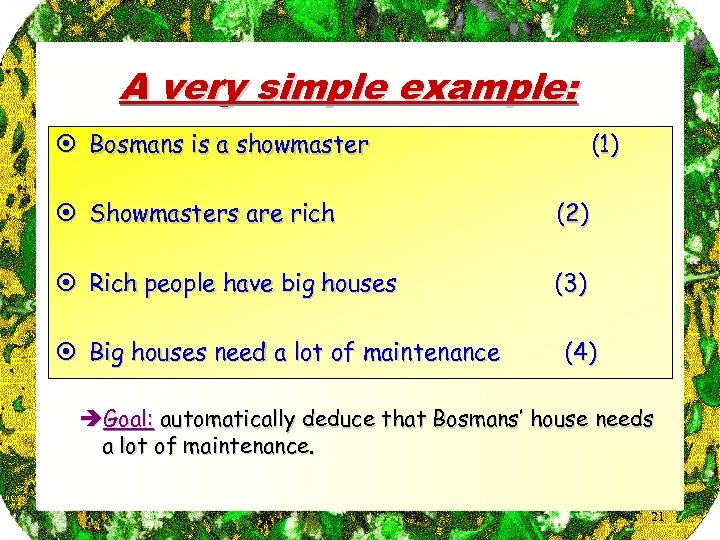

A very simple example: ¤ Bosmans is a showmaster (1) ¤ Showmasters are rich (2) ¤ Rich people have big houses (3) ¤ Big houses need a lot of maintenance (4) èGoal: automatically deduce that Bosmans’ house needs a lot of maintenance. 21

A very simple example: ¤ Bosmans is a showmaster (1) ¤ Showmasters are rich (2) ¤ Rich people have big houses (3) ¤ Big houses need a lot of maintenance (4) èGoal: automatically deduce that Bosmans’ house needs a lot of maintenance. 21

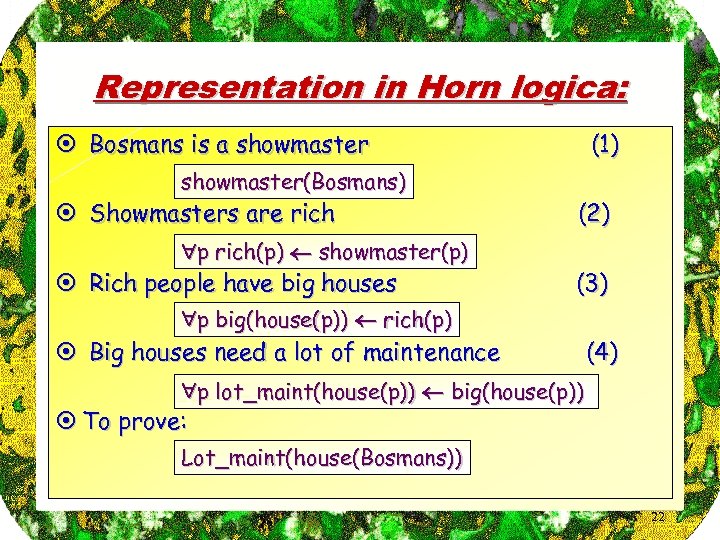

Representation in Horn logica: ¤ Bosmans is a showmaster(Bosmans) ¤ Showmasters are rich p rich(p) showmaster(p) ¤ Rich people have big houses (1) (2) (3) p big(house(p)) rich(p) ¤ Big houses need a lot of maintenance (4) p lot_maint(house(p)) big(house(p)) ¤ To prove: Lot_maint(house(Bosmans)) 22

Representation in Horn logica: ¤ Bosmans is a showmaster(Bosmans) ¤ Showmasters are rich p rich(p) showmaster(p) ¤ Rich people have big houses (1) (2) (3) p big(house(p)) rich(p) ¤ Big houses need a lot of maintenance (4) p lot_maint(house(p)) big(house(p)) ¤ To prove: Lot_maint(house(Bosmans)) 22

AR for ground Horn clause logic Backward reasoning proof procedures based on generalized Modus Ponens

AR for ground Horn clause logic Backward reasoning proof procedures based on generalized Modus Ponens

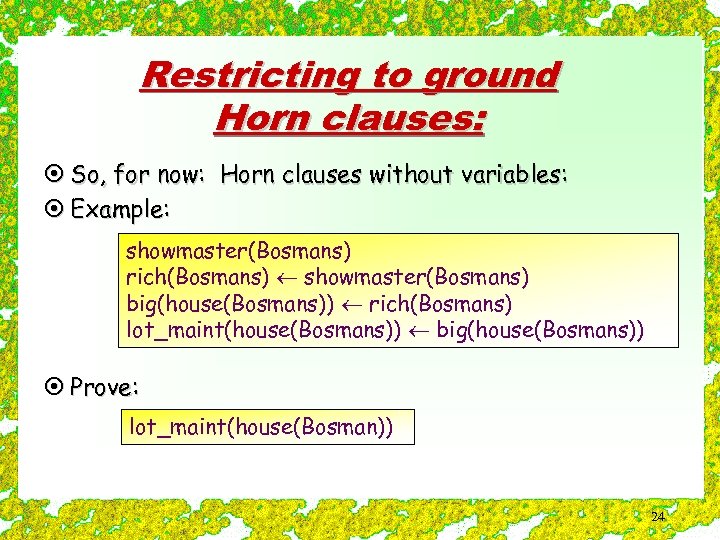

Restricting to ground Horn clauses: ¤ So, for now: Horn clauses without variables: ¤ Example: showmaster(Bosmans) rich(Bosmans) showmaster(Bosmans) big(house(Bosmans)) rich(Bosmans) lot_maint(house(Bosmans)) big(house(Bosmans)) ¤ Prove: lot_maint(house(Bosman)) 24

Restricting to ground Horn clauses: ¤ So, for now: Horn clauses without variables: ¤ Example: showmaster(Bosmans) rich(Bosmans) showmaster(Bosmans) big(house(Bosmans)) rich(Bosmans) lot_maint(house(Bosmans)) big(house(Bosmans)) ¤ Prove: lot_maint(house(Bosman)) 24

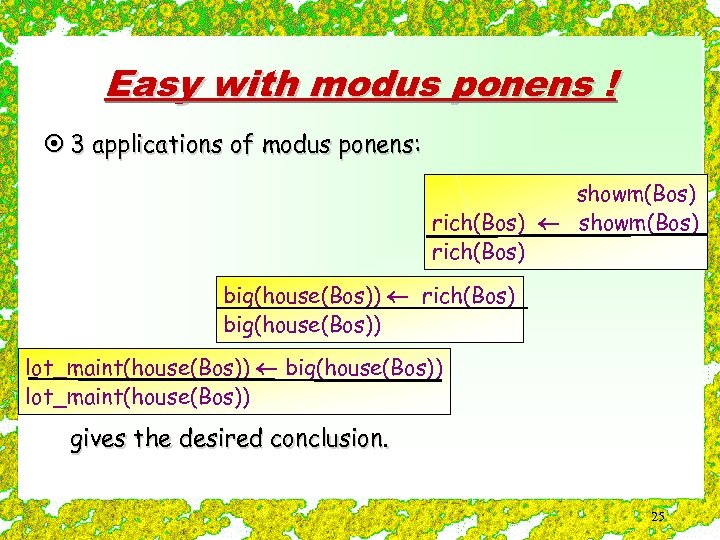

Easy with modus ponens ! ¤ 3 applications of modus ponens: showm(Bos) rich(Bos) big(house(Bos)) lot_maint(house(Bos)) gives the desired conclusion. 25

Easy with modus ponens ! ¤ 3 applications of modus ponens: showm(Bos) rich(Bos) big(house(Bos)) lot_maint(house(Bos)) gives the desired conclusion. 25

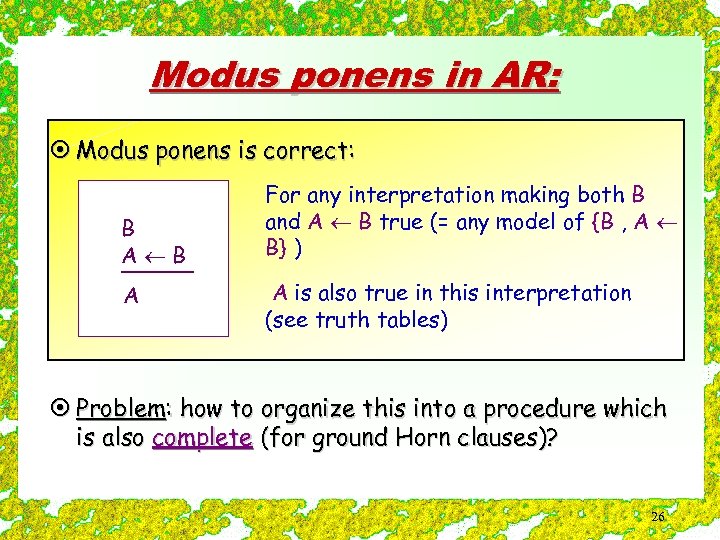

Modus ponens in AR: ¤ Modus ponens is correct: B A For any interpretation making both B and A B true (= any model of {B , A B} ) A is also true in this interpretation (see truth tables) ¤ Problem: how to organize this into a procedure which is also complete (for ground Horn clauses)? 26

Modus ponens in AR: ¤ Modus ponens is correct: B A For any interpretation making both B and A B true (= any model of {B , A B} ) A is also true in this interpretation (see truth tables) ¤ Problem: how to organize this into a procedure which is also complete (for ground Horn clauses)? 26

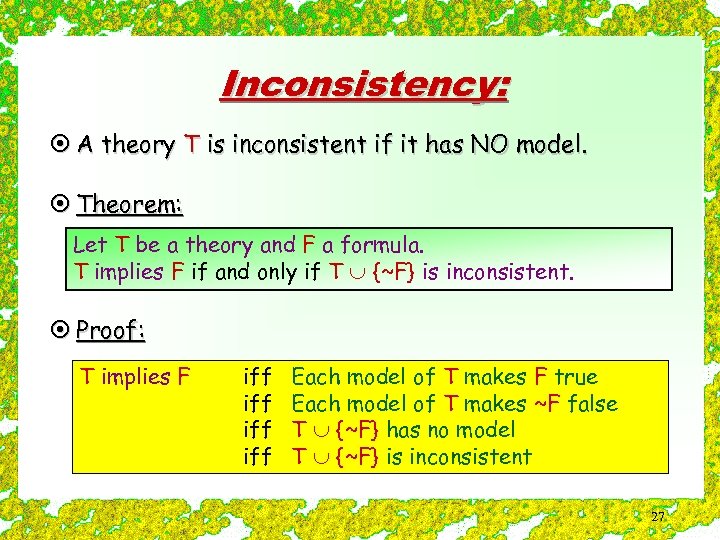

Inconsistency: ¤ A theory T is inconsistent if it has NO model. ¤ Theorem: Let T be a theory and F a formula. T implies F if and only if T {~F} is inconsistent. ¤ Proof: T implies F iff iff Each model of T makes F true Each model of T makes ~F false T {~F} has no model T {~F} is inconsistent 27

Inconsistency: ¤ A theory T is inconsistent if it has NO model. ¤ Theorem: Let T be a theory and F a formula. T implies F if and only if T {~F} is inconsistent. ¤ Proof: T implies F iff iff Each model of T makes F true Each model of T makes ~F false T {~F} has no model T {~F} is inconsistent 27

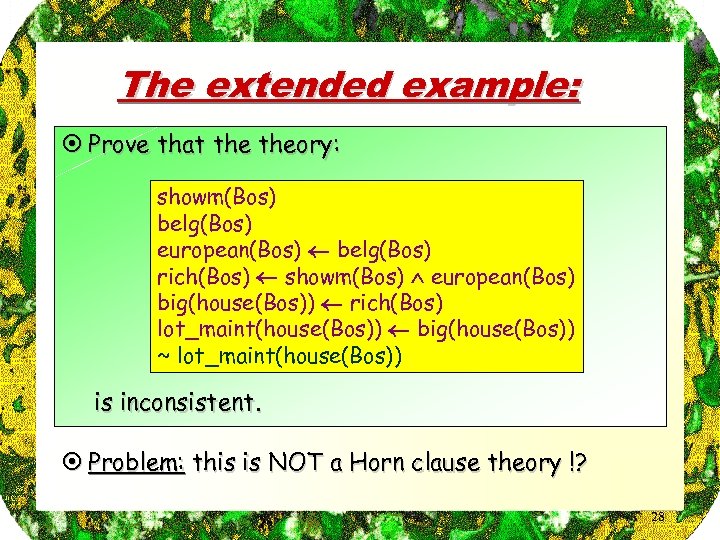

The extended example: ¤ Prove that theory: showm(Bos) belg(Bos) european(Bos) belg(Bos) rich(Bos) showm(Bos) european(Bos) big(house(Bos)) rich(Bos) lot_maint(house(Bos)) big(house(Bos)) ~ lot_maint(house(Bos)) is inconsistent. ¤ Problem: this is NOT a Horn clause theory !? 28

The extended example: ¤ Prove that theory: showm(Bos) belg(Bos) european(Bos) belg(Bos) rich(Bos) showm(Bos) european(Bos) big(house(Bos)) rich(Bos) lot_maint(house(Bos)) big(house(Bos)) ~ lot_maint(house(Bos)) is inconsistent. ¤ Problem: this is NOT a Horn clause theory !? 28

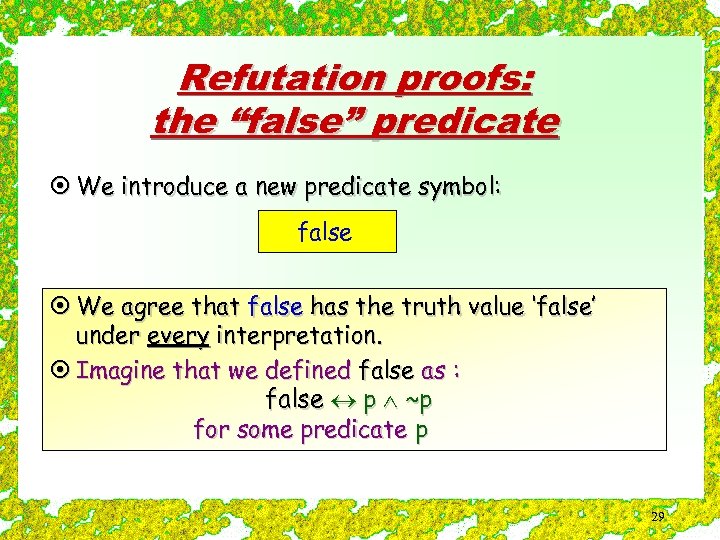

Refutation proofs: the “false” predicate ¤ We introduce a new predicate symbol: false ¤ We agree that false has the truth value ‘false’ under every interpretation. ¤ Imagine that we defined false as : false p ~p for some predicate p 29

Refutation proofs: the “false” predicate ¤ We introduce a new predicate symbol: false ¤ We agree that false has the truth value ‘false’ under every interpretation. ¤ Imagine that we defined false as : false p ~p for some predicate p 29

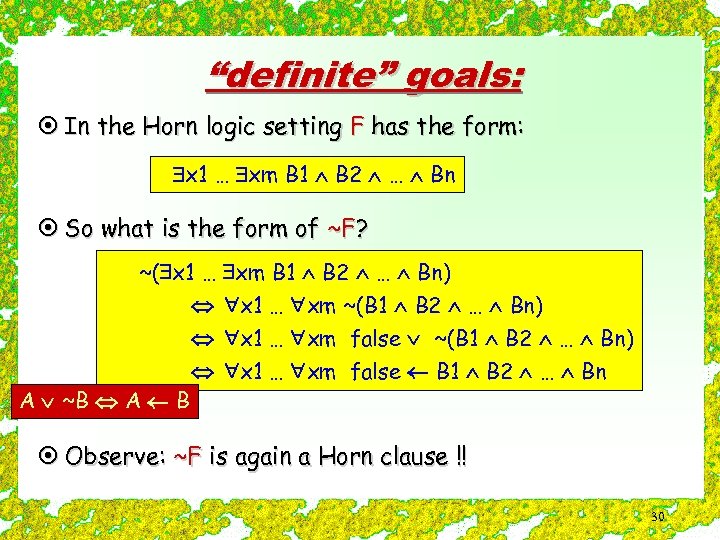

“definite” goals: ¤ In the Horn logic setting F has the form: x 1 … xm B 1 B 2 … Bn ¤ So what is the form of ~F? ~( x 1 … xm B 1 B 2 … Bn) x 1 … xm ~(B 1 B 2 … Bn) A ~B A B x 1 … xm false ~(B 1 B 2 … Bn) x 1 … xm false B 1 B 2 … Bn ¤ Observe: ~F is again a Horn clause !! 30

“definite” goals: ¤ In the Horn logic setting F has the form: x 1 … xm B 1 B 2 … Bn ¤ So what is the form of ~F? ~( x 1 … xm B 1 B 2 … Bn) x 1 … xm ~(B 1 B 2 … Bn) A ~B A B x 1 … xm false ~(B 1 B 2 … Bn) x 1 … xm false B 1 B 2 … Bn ¤ Observe: ~F is again a Horn clause !! 30

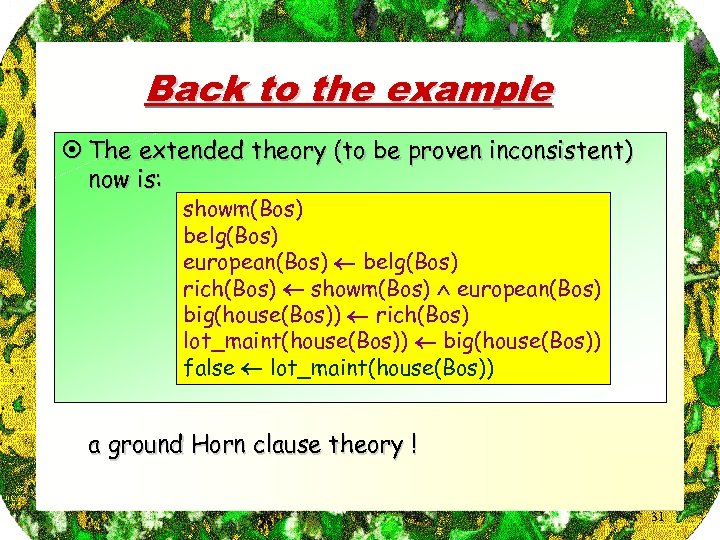

Back to the example ¤ The extended theory (to be proven inconsistent) now is: showm(Bos) belg(Bos) european(Bos) belg(Bos) rich(Bos) showm(Bos) european(Bos) big(house(Bos)) rich(Bos) lot_maint(house(Bos)) big(house(Bos)) false lot_maint(house(Bos)) a ground Horn clause theory ! 31

Back to the example ¤ The extended theory (to be proven inconsistent) now is: showm(Bos) belg(Bos) european(Bos) belg(Bos) rich(Bos) showm(Bos) european(Bos) big(house(Bos)) rich(Bos) lot_maint(house(Bos)) big(house(Bos)) false lot_maint(house(Bos)) a ground Horn clause theory ! 31

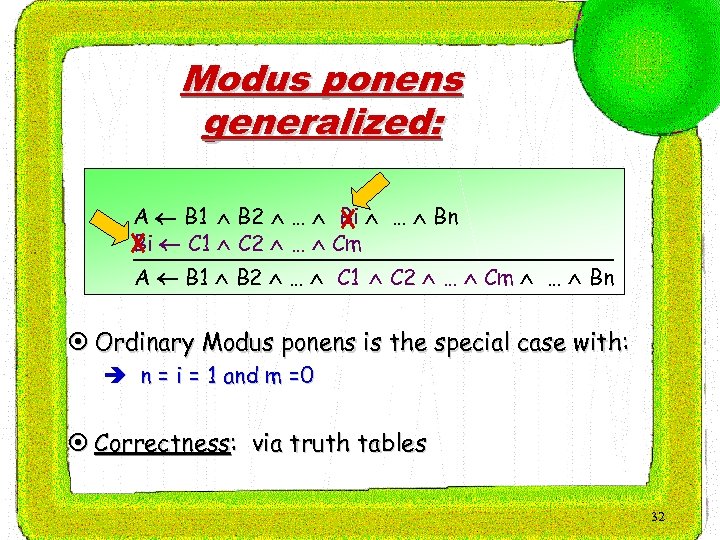

Modus ponens generalized: A B 1 B 2 … Bi … Bn Bi C 1 C 2 … Cm A B 1 B 2 … C 1 C 2 … Cm … Bn ¤ Ordinary Modus ponens is the special case with: è n = i = 1 and m =0 ¤ Correctness: via truth tables 32

Modus ponens generalized: A B 1 B 2 … Bi … Bn Bi C 1 C 2 … Cm A B 1 B 2 … C 1 C 2 … Cm … Bn ¤ Ordinary Modus ponens is the special case with: è n = i = 1 and m =0 ¤ Correctness: via truth tables 32

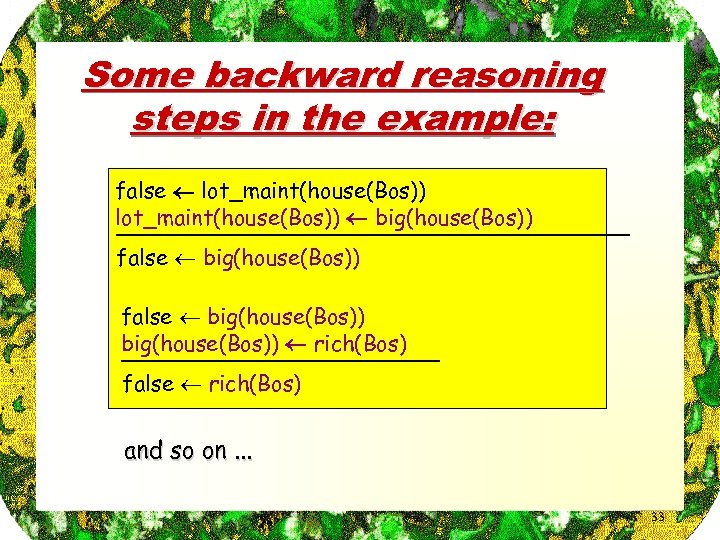

Some backward reasoning steps in the example: false lot_maint(house(Bos)) big(house(Bos)) false big(house(Bos)) rich(Bos) false rich(Bos) and so on. . . 33

Some backward reasoning steps in the example: false lot_maint(house(Bos)) big(house(Bos)) false big(house(Bos)) rich(Bos) false rich(Bos) and so on. . . 33

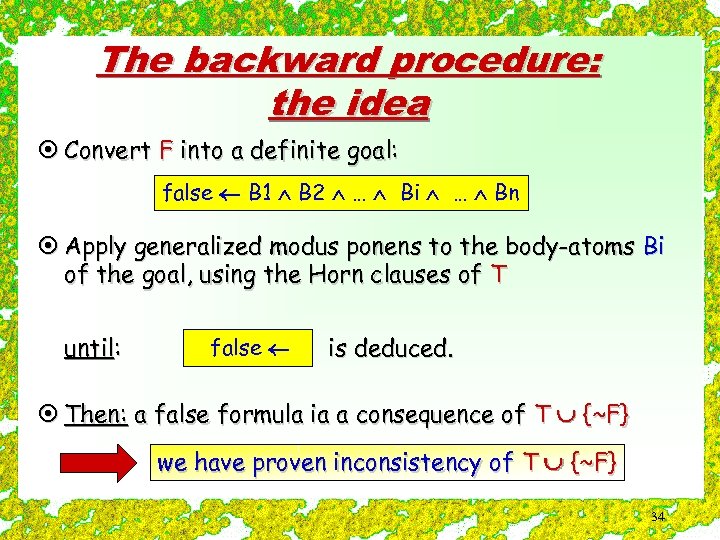

The backward procedure: the idea ¤ Convert F into a definite goal: false B 1 B 2 … Bi … Bn ¤ Apply generalized modus ponens to the body-atoms Bi of the goal, using the Horn clauses of T until: false is deduced. ¤ Then: a false formula ia a consequence of T {~F} we have proven inconsistency of T {~F} 34

The backward procedure: the idea ¤ Convert F into a definite goal: false B 1 B 2 … Bi … Bn ¤ Apply generalized modus ponens to the body-atoms Bi of the goal, using the Horn clauses of T until: false is deduced. ¤ Then: a false formula ia a consequence of T {~F} we have proven inconsistency of T {~F} 34

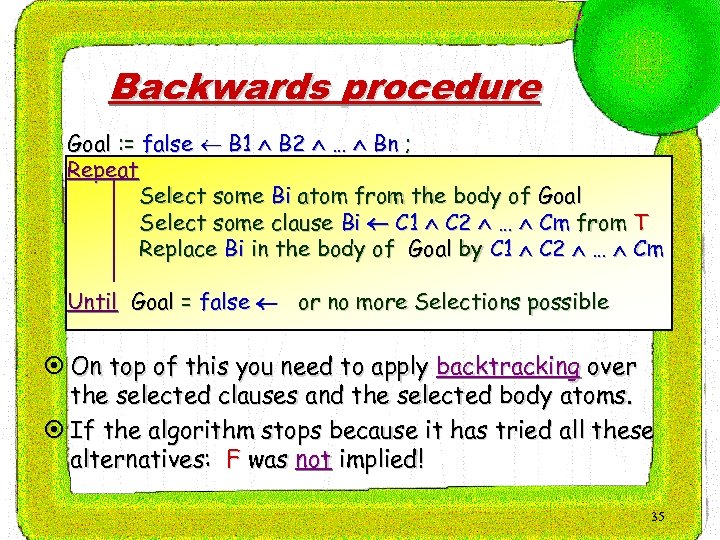

Backwards procedure Goal : = false B 1 B 2 … Bn ; Repeat Select some Bi atom from the body of Goal Select some clause Bi C 1 C 2 … Cm from T Replace Bi in the body of Goal by C 1 C 2 … Cm Until Goal = false or no more Selections possible ¤ On top of this you need to apply backtracking over the selected clauses and the selected body atoms. ¤ If the algorithm stops because it has tried all these alternatives: F was not implied! 35

Backwards procedure Goal : = false B 1 B 2 … Bn ; Repeat Select some Bi atom from the body of Goal Select some clause Bi C 1 C 2 … Cm from T Replace Bi in the body of Goal by C 1 C 2 … Cm Until Goal = false or no more Selections possible ¤ On top of this you need to apply backtracking over the selected clauses and the selected body atoms. ¤ If the algorithm stops because it has tried all these alternatives: F was not implied! 35

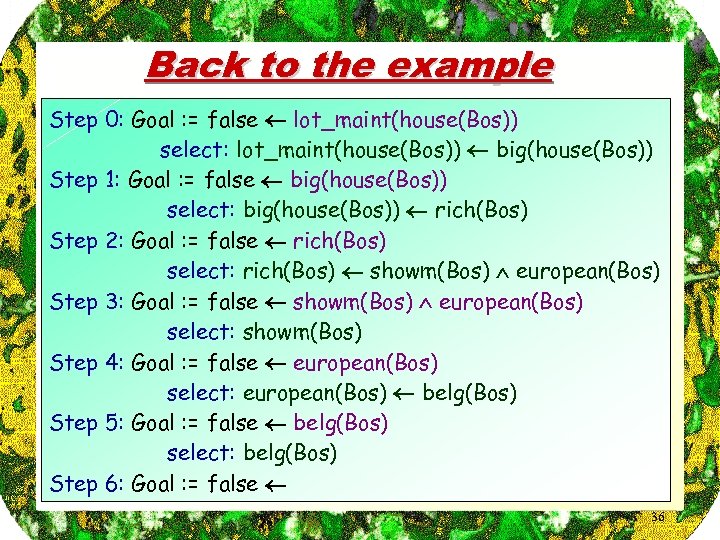

Back to the example Step 0: Goal : = false lot_maint(house(Bos)) select: lot_maint(house(Bos)) big(house(Bos)) Step 1: Goal : = false big(house(Bos)) select: big(house(Bos)) rich(Bos) Step 2: Goal : = false rich(Bos) select: rich(Bos) showm(Bos) european(Bos) Step 3: Goal : = false showm(Bos) european(Bos) select: showm(Bos) Step 4: Goal : = false european(Bos) select: european(Bos) belg(Bos) Step 5: Goal : = false belg(Bos) select: belg(Bos) Step 6: Goal : = false 36

Back to the example Step 0: Goal : = false lot_maint(house(Bos)) select: lot_maint(house(Bos)) big(house(Bos)) Step 1: Goal : = false big(house(Bos)) select: big(house(Bos)) rich(Bos) Step 2: Goal : = false rich(Bos) select: rich(Bos) showm(Bos) european(Bos) Step 3: Goal : = false showm(Bos) european(Bos) select: showm(Bos) Step 4: Goal : = false european(Bos) select: european(Bos) belg(Bos) Step 5: Goal : = false belg(Bos) select: belg(Bos) Step 6: Goal : = false 36

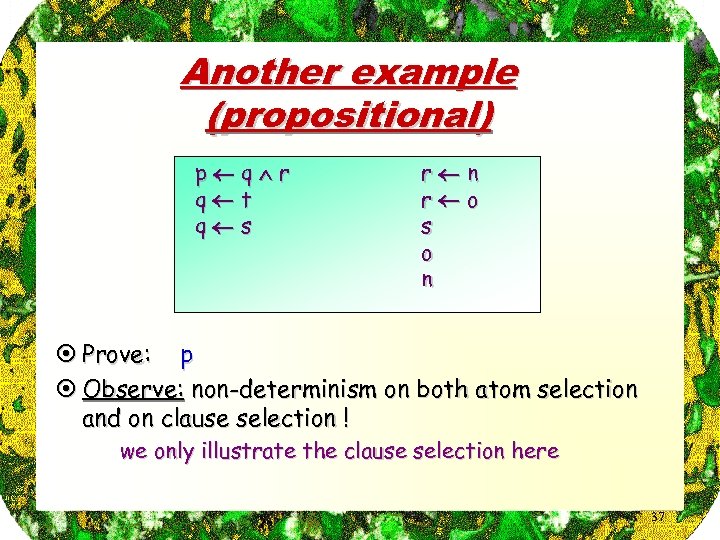

Another example (propositional) p q r q t q s r n r o s o n ¤ Prove: p ¤ Observe: non-determinism on both atom selection and on clause selection ! we only illustrate the clause selection here 37

Another example (propositional) p q r q t q s r n r o s o n ¤ Prove: p ¤ Observe: non-determinism on both atom selection and on clause selection ! we only illustrate the clause selection here 37

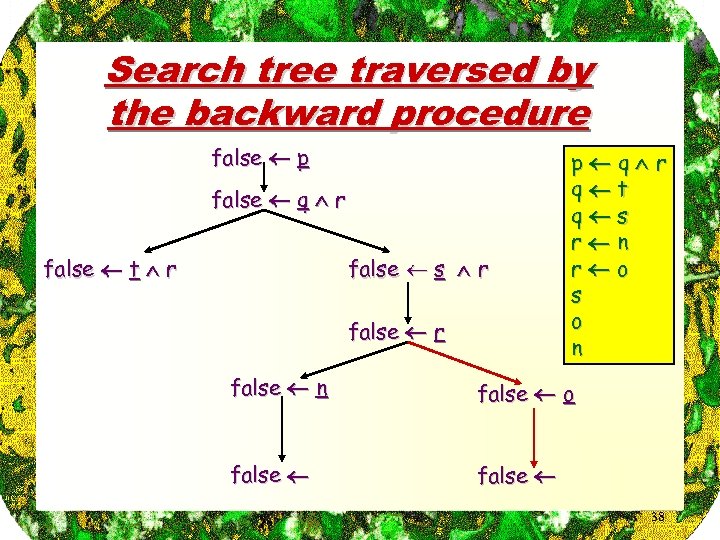

Search tree traversed by the backward procedure false p false q r false t r false s r false r p q r q t q s r n r o s o n false o false 38

Search tree traversed by the backward procedure false p false q r false t r false s r false r p q r q t q s r n r o s o n false o false 38

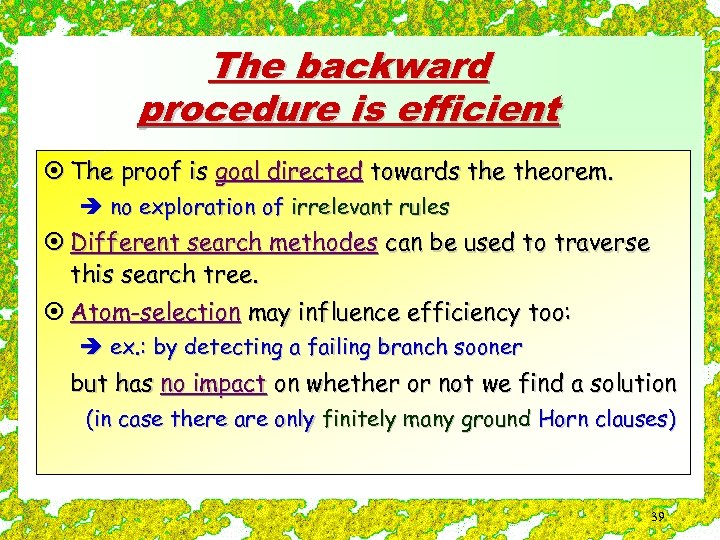

The backward procedure is efficient ¤ The proof is goal directed towards theorem. è no exploration of irrelevant rules ¤ Different search methodes can be used to traverse this search tree. ¤ Atom-selection may influence efficiency too: è ex. : by detecting a failing branch sooner but has no impact on whether or not we find a solution (in case there are only finitely many ground Horn clauses) 39

The backward procedure is efficient ¤ The proof is goal directed towards theorem. è no exploration of irrelevant rules ¤ Different search methodes can be used to traverse this search tree. ¤ Atom-selection may influence efficiency too: è ex. : by detecting a failing branch sooner but has no impact on whether or not we find a solution (in case there are only finitely many ground Horn clauses) 39

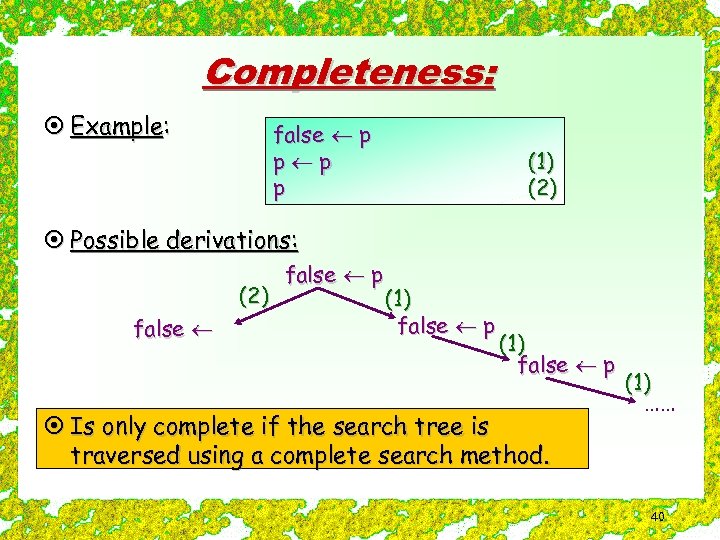

Completeness: ¤ Example: false p p (1) (2) ¤ Possible derivations: (2) false p (1) false p ¤ Is only complete if the search tree is traversed using a complete search method. (1) …… 40

Completeness: ¤ Example: false p p (1) (2) ¤ Possible derivations: (2) false p (1) false p ¤ Is only complete if the search tree is traversed using a complete search method. (1) …… 40

Representation-power of ground Horn clauses ¤ Is a subset of propositional logic. ¤ Example: showm(Bos) showm_Bos big(house(Bos)) big_house_Bos ¤ In general, more expressive logics are needed. è Essence: with variables, one formula may be equivalent to a very large number of propositional formulae. 41

Representation-power of ground Horn clauses ¤ Is a subset of propositional logic. ¤ Example: showm(Bos) showm_Bos big(house(Bos)) big_house_Bos ¤ In general, more expressive logics are needed. è Essence: with variables, one formula may be equivalent to a very large number of propositional formulae. 41