e56a22beb1607417098d5b236d52dd63.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 51

Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers Kip Irvine Chapter 4: Data Transfers, Addressing, and Arithmetic

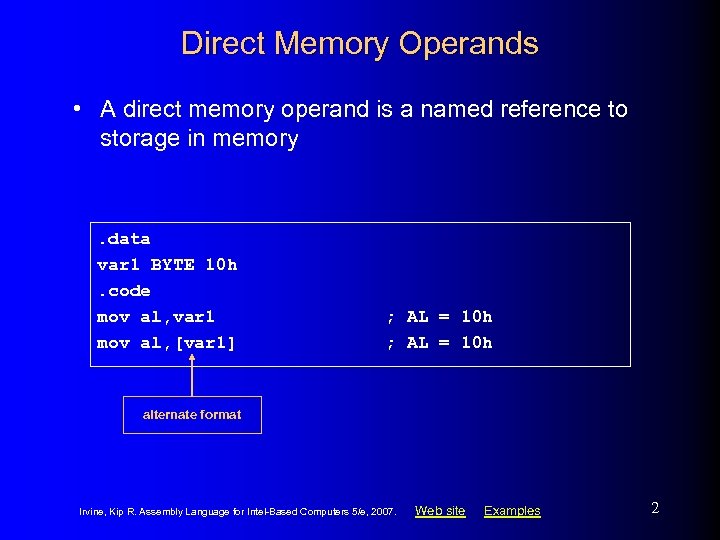

Direct Memory Operands • A direct memory operand is a named reference to storage in memory . data var 1 BYTE 10 h. code mov al, var 1 mov al, [var 1] ; AL = 10 h alternate format Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 2

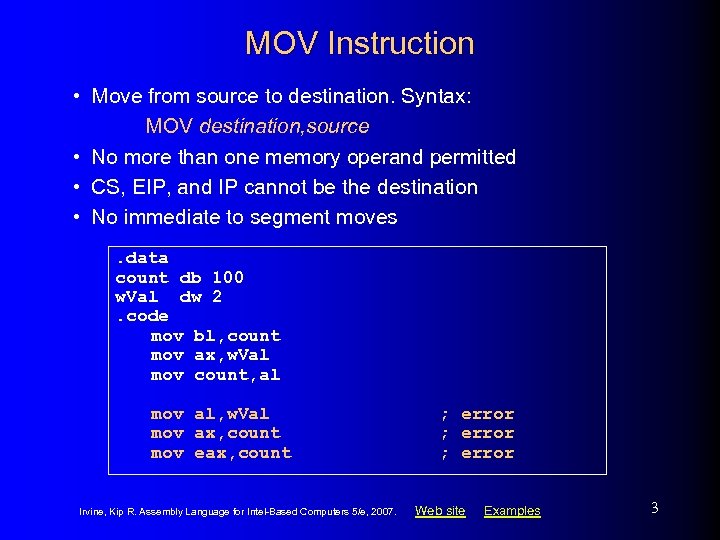

MOV Instruction • Move from source to destination. Syntax: MOV destination, source • No more than one memory operand permitted • CS, EIP, and IP cannot be the destination • No immediate to segment moves. data count db 100 w. Val dw 2. code mov bl, count mov ax, w. Val mov count, al mov al, w. Val mov ax, count mov eax, count Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. ; error Web site Examples 3

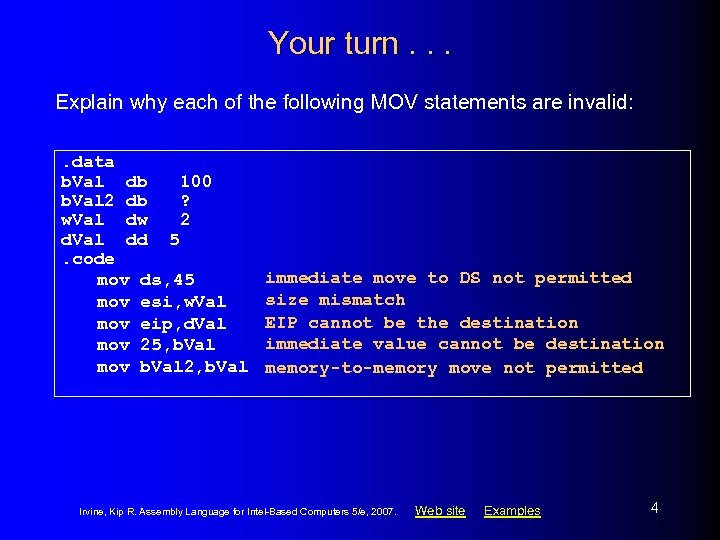

Your turn. . . Explain why each of the following MOV statements are invalid: . data b. Val db 100 b. Val 2 db ? w. Val dw 2 d. Val dd 5. code mov ds, 45 mov esi, w. Val mov eip, d. Val mov 25, b. Val mov b. Val 2, b. Val immediate move to DS not permitted size mismatch EIP cannot be the destination immediate value cannot be destination memory-to-memory move not permitted Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 4

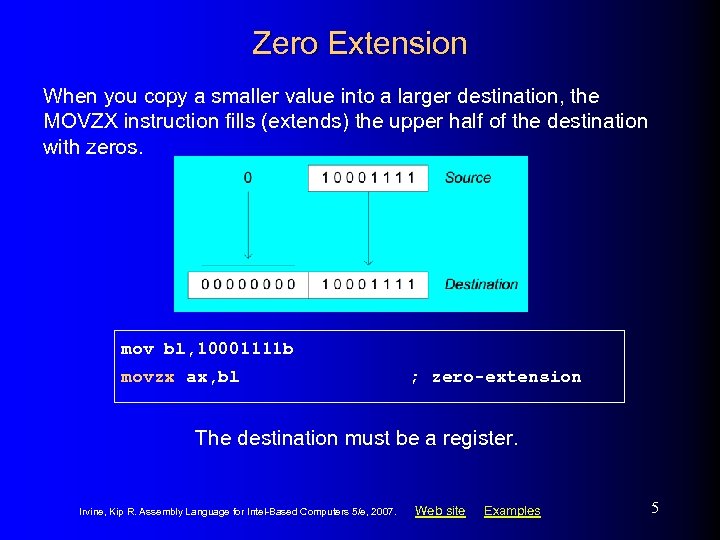

Zero Extension When you copy a smaller value into a larger destination, the MOVZX instruction fills (extends) the upper half of the destination with zeros. mov bl, 10001111 b movzx ax, bl ; zero-extension The destination must be a register. Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 5

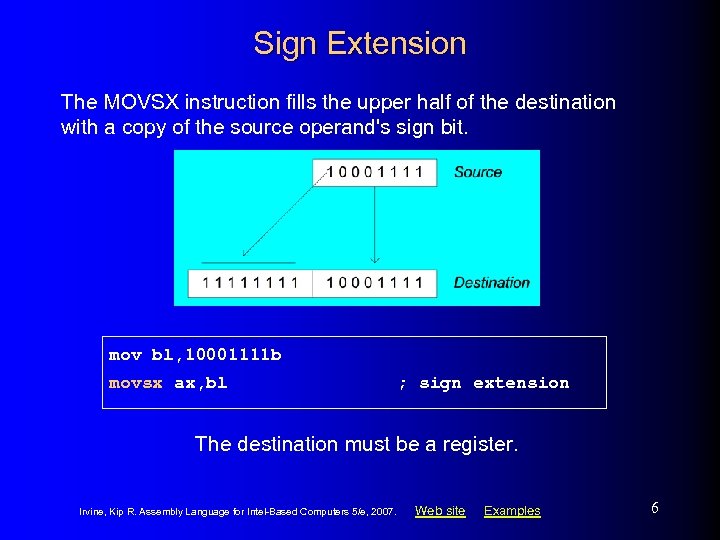

Sign Extension The MOVSX instruction fills the upper half of the destination with a copy of the source operand's sign bit. mov bl, 10001111 b movsx ax, bl ; sign extension The destination must be a register. Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 6

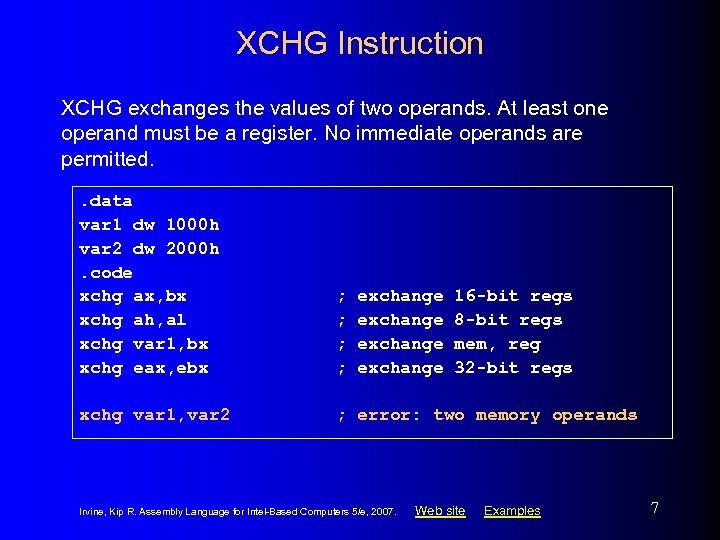

XCHG Instruction XCHG exchanges the values of two operands. At least one operand must be a register. No immediate operands are permitted. . data var 1 dw 1000 h var 2 dw 2000 h. code xchg ax, bx xchg ah, al xchg var 1, bx xchg eax, ebx ; ; xchg var 1, var 2 ; error: two memory operands exchange Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. 16 -bit regs 8 -bit regs mem, reg 32 -bit regs Web site Examples 7

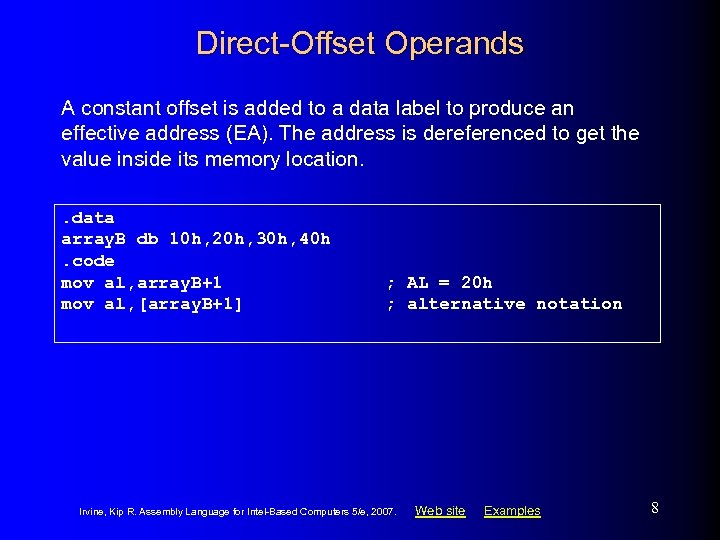

Direct-Offset Operands A constant offset is added to a data label to produce an effective address (EA). The address is dereferenced to get the value inside its memory location. . data array. B db 10 h, 20 h, 30 h, 40 h. code mov al, array. B+1 mov al, [array. B+1] ; AL = 20 h ; alternative notation Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 8

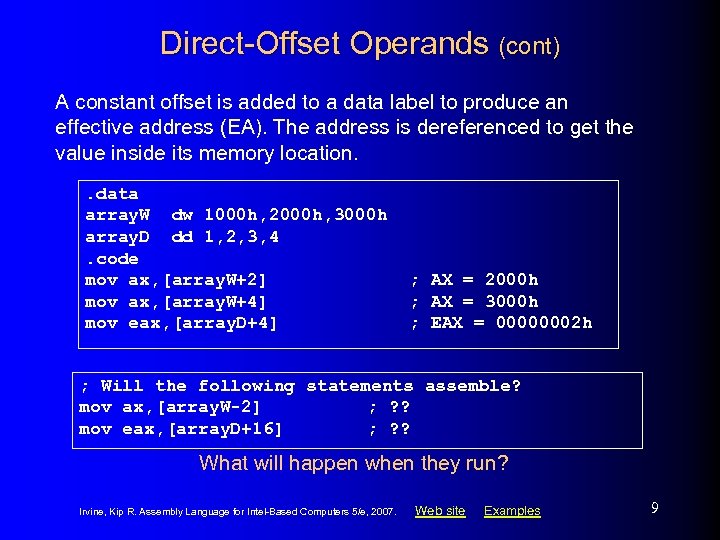

Direct-Offset Operands (cont) A constant offset is added to a data label to produce an effective address (EA). The address is dereferenced to get the value inside its memory location. . data array. W dw 1000 h, 2000 h, 3000 h array. D dd 1, 2, 3, 4. code mov ax, [array. W+2] mov ax, [array. W+4] mov eax, [array. D+4] ; AX = 2000 h ; AX = 3000 h ; EAX = 00000002 h ; Will the following statements assemble? mov ax, [array. W-2] ; ? ? mov eax, [array. D+16] ; ? ? What will happen when they run? Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 9

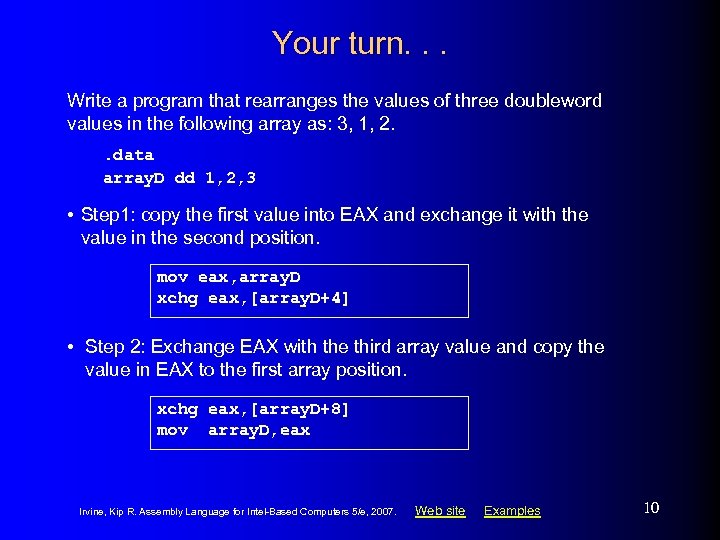

Your turn. . . Write a program that rearranges the values of three doubleword values in the following array as: 3, 1, 2. . data array. D dd 1, 2, 3 • Step 1: copy the first value into EAX and exchange it with the value in the second position. mov eax, array. D xchg eax, [array. D+4] • Step 2: Exchange EAX with the third array value and copy the value in EAX to the first array position. xchg eax, [array. D+8] mov array. D, eax Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 10

Addition and Subtraction • • • INC and DEC Instructions ADD and SUB Instructions NEG Instruction Implementing Arithmetic Expressions Flags Affected by Arithmetic • • Zero Sign Carry Overflow Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 11

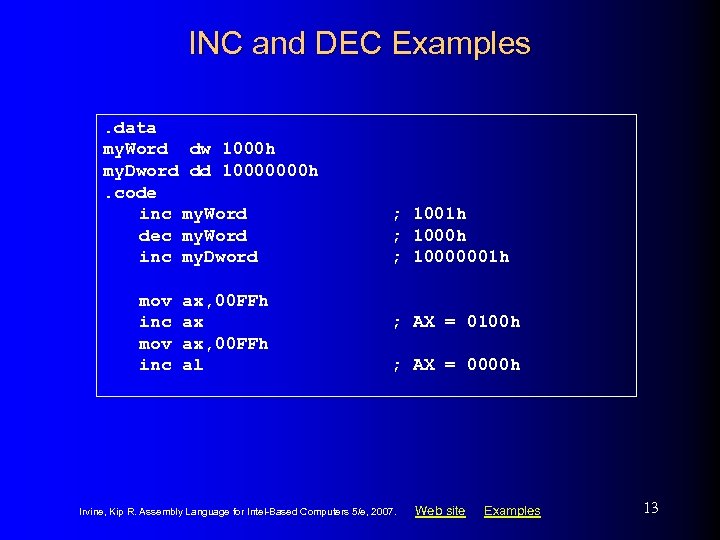

INC and DEC Instructions • Add 1, subtract 1 from destination operand • operand may be register or memory • INC destination • destination + 1 • DEC destination • destination – 1 Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 12

INC and DEC Examples. data my. Word dw 1000 h my. Dword dd 10000000 h. code inc my. Word dec my. Word inc my. Dword mov inc ax, 00 FFh ax ax, 00 FFh al ; 1001 h ; 10000001 h ; AX = 0100 h ; AX = 0000 h Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 13

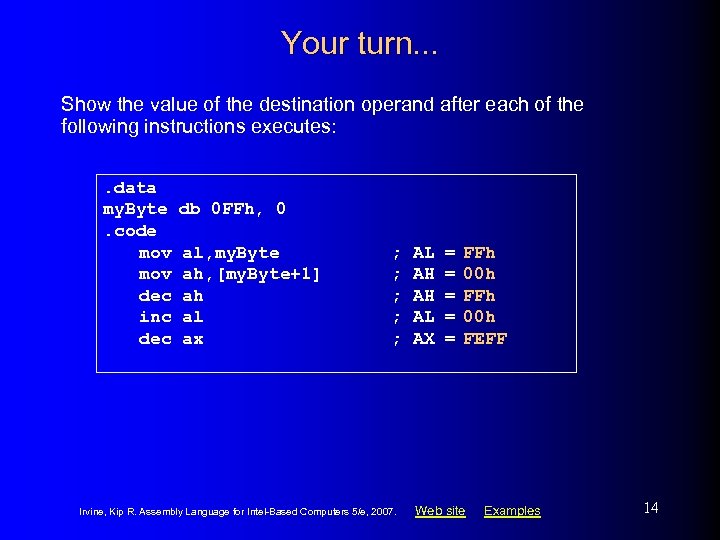

Your turn. . . Show the value of the destination operand after each of the following instructions executes: . data my. Byte. code mov dec inc dec db 0 FFh, 0 al, my. Byte ah, [my. Byte+1] ah al ax ; ; ; Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. AL AH AH AL AX = = = FFh 00 h FEFF Web site Examples 14

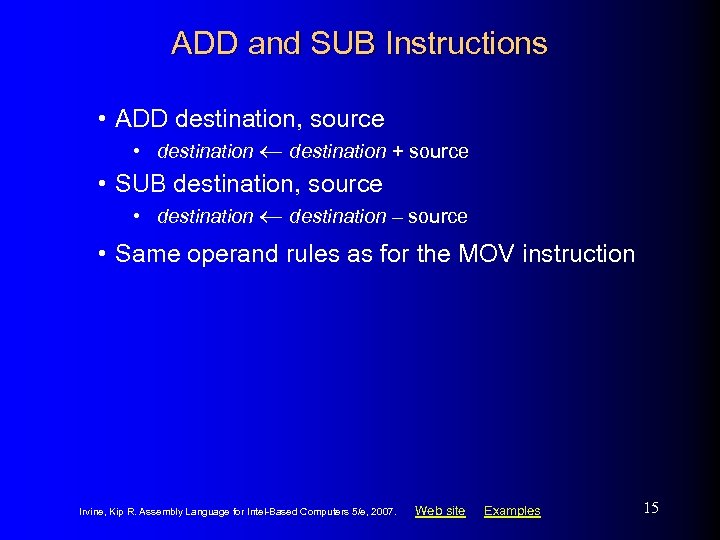

ADD and SUB Instructions • ADD destination, source • destination + source • SUB destination, source • destination – source • Same operand rules as for the MOV instruction Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 15

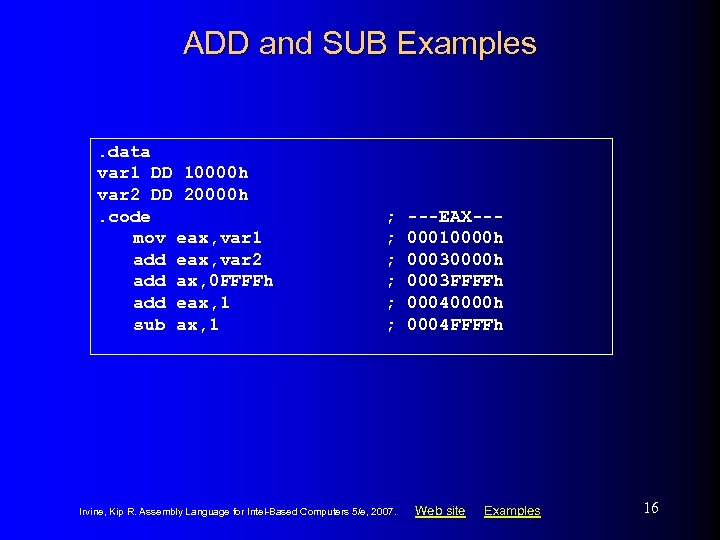

ADD and SUB Examples. data var 1 DD 10000 h var 2 DD 20000 h. code mov eax, var 1 add eax, var 2 add ax, 0 FFFFh add eax, 1 sub ax, 1 ; ; ; Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. ---EAX--00010000 h 0003 FFFFh 00040000 h 0004 FFFFh Web site Examples 16

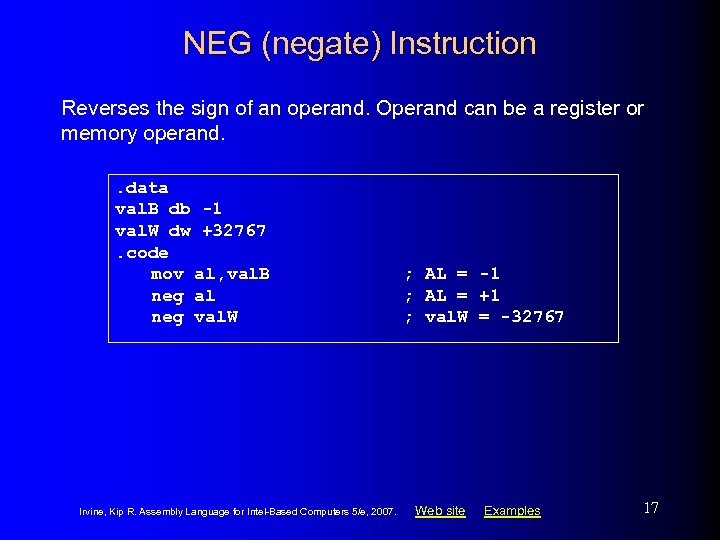

NEG (negate) Instruction Reverses the sign of an operand. Operand can be a register or memory operand. . data val. B db -1 val. W dw +32767. code mov al, val. B neg al neg val. W Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. ; AL = -1 ; AL = +1 ; val. W = -32767 Web site Examples 17

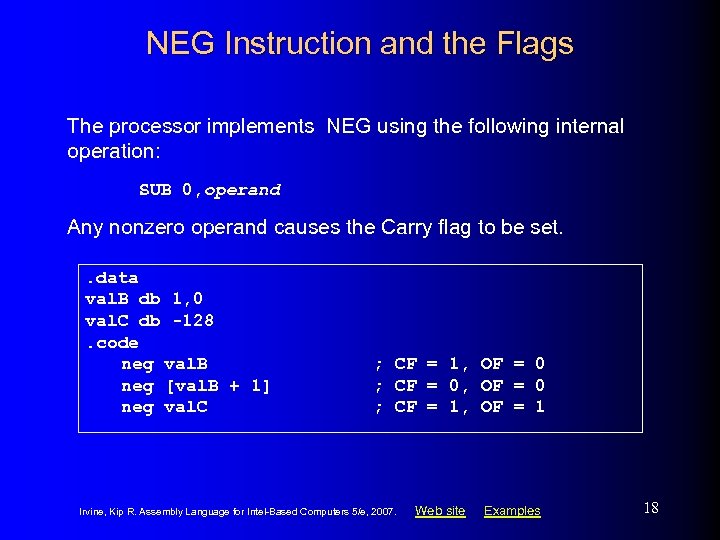

NEG Instruction and the Flags The processor implements NEG using the following internal operation: SUB 0, operand Any nonzero operand causes the Carry flag to be set. . data val. B db 1, 0 val. C db -128. code neg val. B neg [val. B + 1] neg val. C ; CF = 1, OF = 0 ; CF = 0, OF = 0 ; CF = 1, OF = 1 Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 18

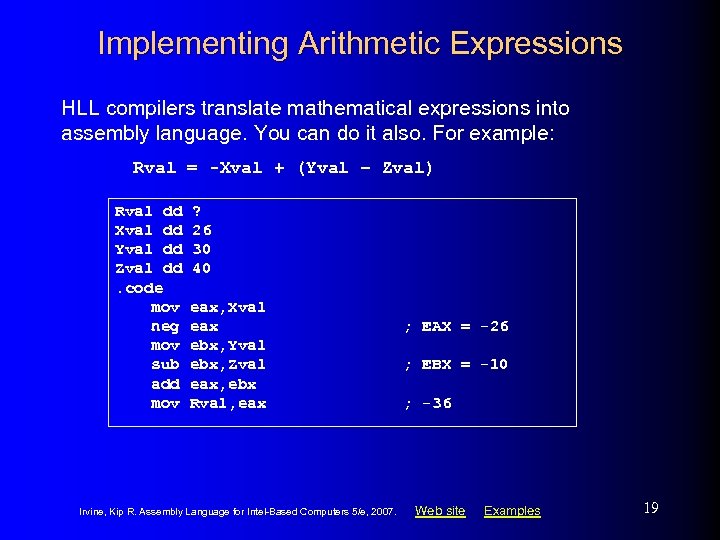

Implementing Arithmetic Expressions HLL compilers translate mathematical expressions into assembly language. You can do it also. For example: Rval = -Xval + (Yval – Zval) Rval dd Xval dd Yval dd Zval dd. code mov neg mov sub add mov ? 26 30 40 eax, Xval eax ebx, Yval ebx, Zval eax, ebx Rval, eax Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. ; EAX = -26 ; EBX = -10 ; -36 Web site Examples 19

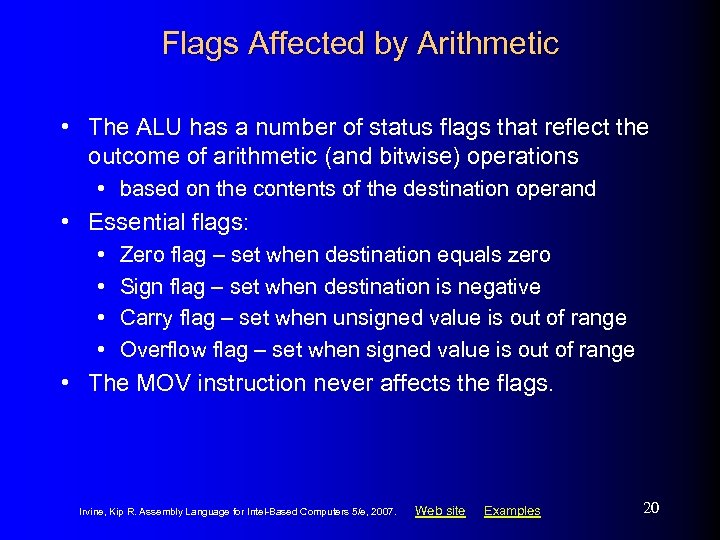

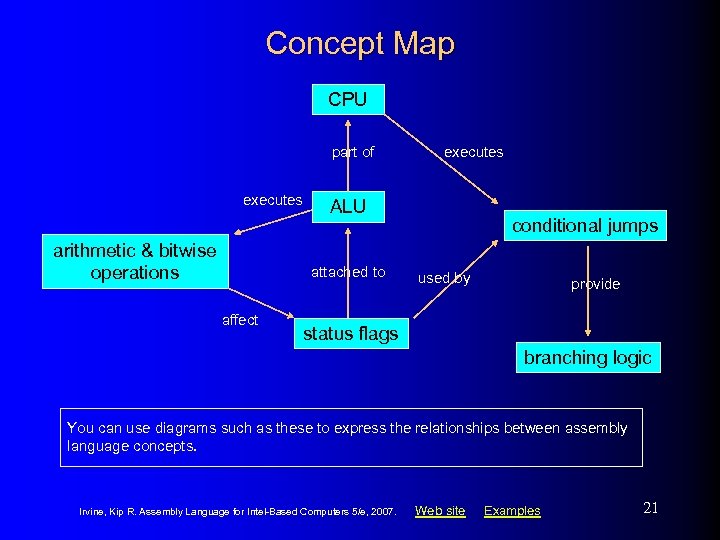

Flags Affected by Arithmetic • The ALU has a number of status flags that reflect the outcome of arithmetic (and bitwise) operations • based on the contents of the destination operand • Essential flags: • • Zero flag – set when destination equals zero Sign flag – set when destination is negative Carry flag – set when unsigned value is out of range Overflow flag – set when signed value is out of range • The MOV instruction never affects the flags. Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 20

Concept Map CPU part of executes arithmetic & bitwise operations ALU attached to affect executes conditional jumps used by provide status flags branching logic You can use diagrams such as these to express the relationships between assembly language concepts. Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 21

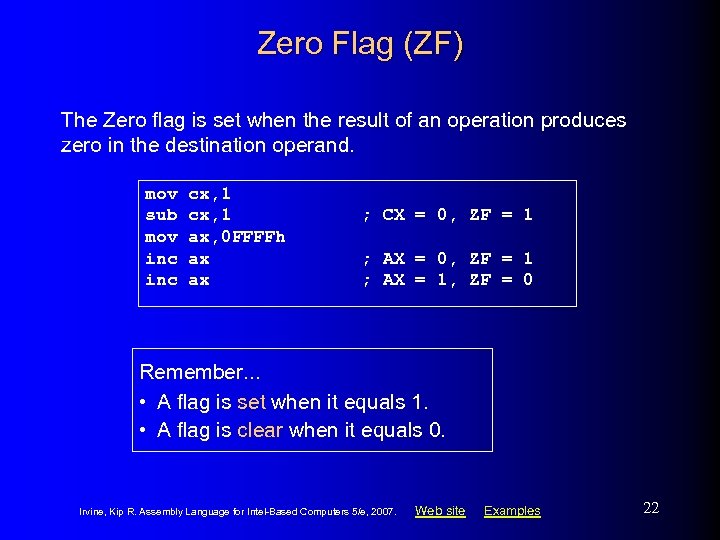

Zero Flag (ZF) The Zero flag is set when the result of an operation produces zero in the destination operand. mov sub mov inc cx, 1 ax, 0 FFFFh ax ax ; CX = 0, ZF = 1 ; AX = 1, ZF = 0 Remember. . . • A flag is set when it equals 1. • A flag is clear when it equals 0. Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 22

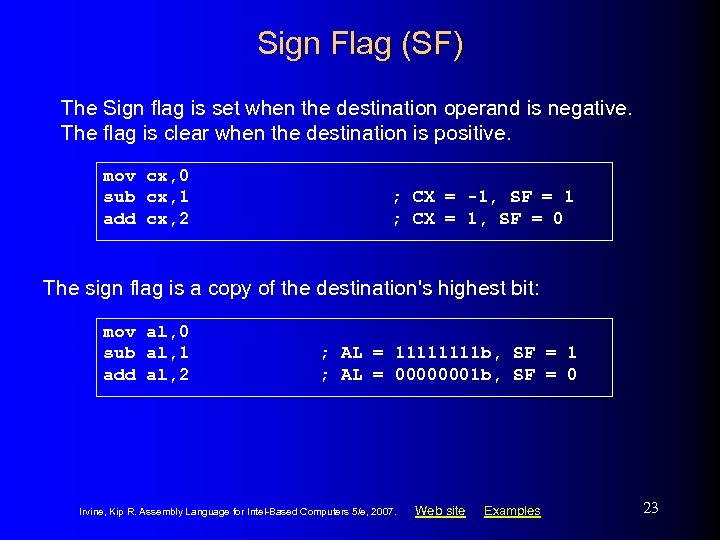

Sign Flag (SF) The Sign flag is set when the destination operand is negative. The flag is clear when the destination is positive. mov cx, 0 sub cx, 1 add cx, 2 ; CX = -1, SF = 1 ; CX = 1, SF = 0 The sign flag is a copy of the destination's highest bit: mov al, 0 sub al, 1 add al, 2 ; AL = 1111 b, SF = 1 ; AL = 00000001 b, SF = 0 Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 23

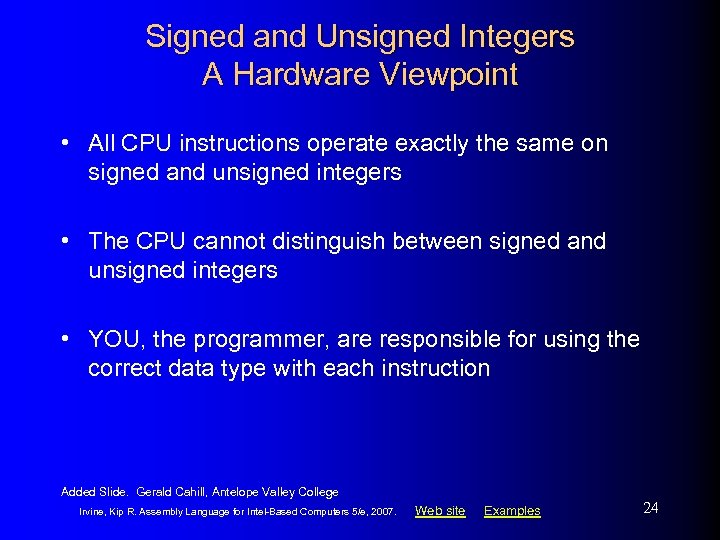

Signed and Unsigned Integers A Hardware Viewpoint • All CPU instructions operate exactly the same on signed and unsigned integers • The CPU cannot distinguish between signed and unsigned integers • YOU, the programmer, are responsible for using the correct data type with each instruction Added Slide. Gerald Cahill, Antelope Valley College Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 24

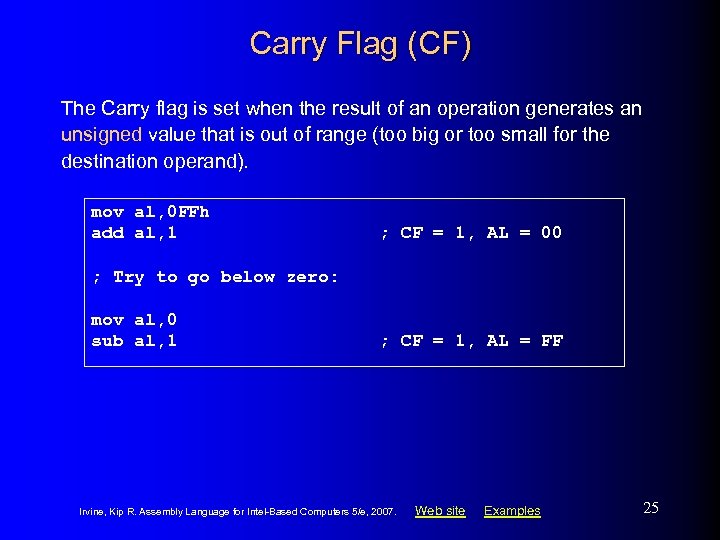

Carry Flag (CF) The Carry flag is set when the result of an operation generates an unsigned value that is out of range (too big or too small for the destination operand). mov al, 0 FFh add al, 1 ; CF = 1, AL = 00 ; Try to go below zero: mov al, 0 sub al, 1 ; CF = 1, AL = FF Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 25

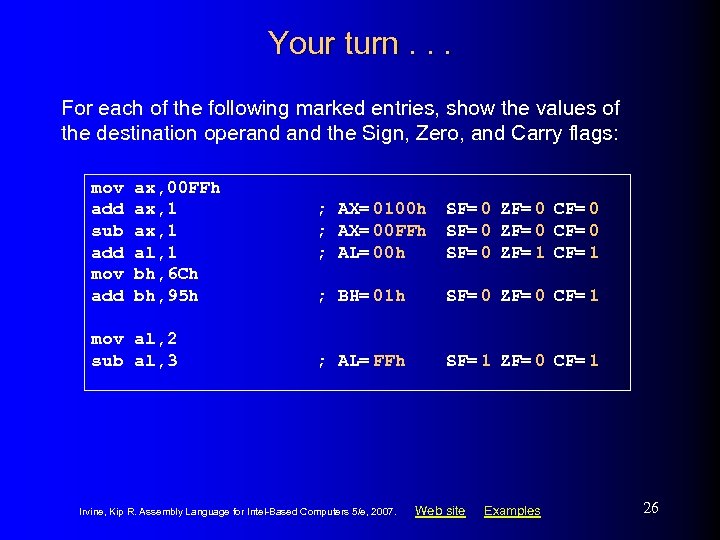

Your turn. . . For each of the following marked entries, show the values of the destination operand the Sign, Zero, and Carry flags: mov add sub add mov add ax, 00 FFh ax, 1 al, 1 bh, 6 Ch bh, 95 h mov al, 2 sub al, 3 ; AX= 0100 h ; AX= 00 FFh ; AL= 00 h SF= 0 ZF= 0 CF= 0 SF= 0 ZF= 1 CF= 1 ; BH= 01 h SF= 0 ZF= 0 CF= 1 ; AL= FFh SF= 1 ZF= 0 CF= 1 Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 26

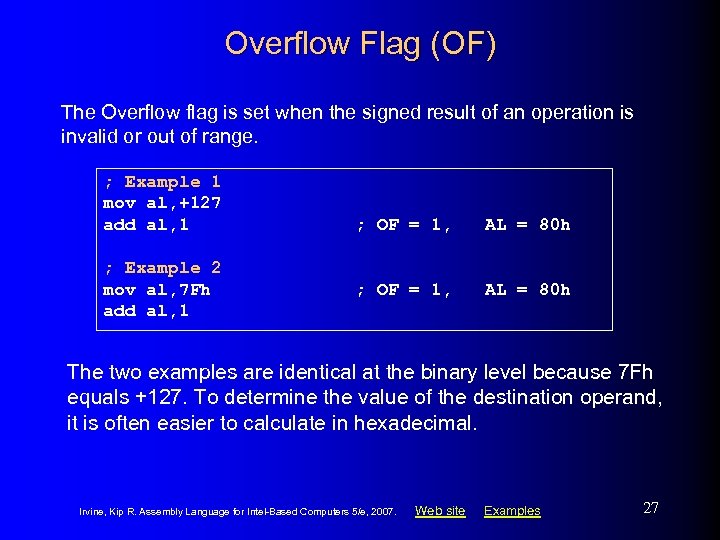

Overflow Flag (OF) The Overflow flag is set when the signed result of an operation is invalid or out of range. ; Example 1 mov al, +127 add al, 1 ; Example 2 mov al, 7 Fh add al, 1 ; OF = 1, AL = 80 h The two examples are identical at the binary level because 7 Fh equals +127. To determine the value of the destination operand, it is often easier to calculate in hexadecimal. Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 27

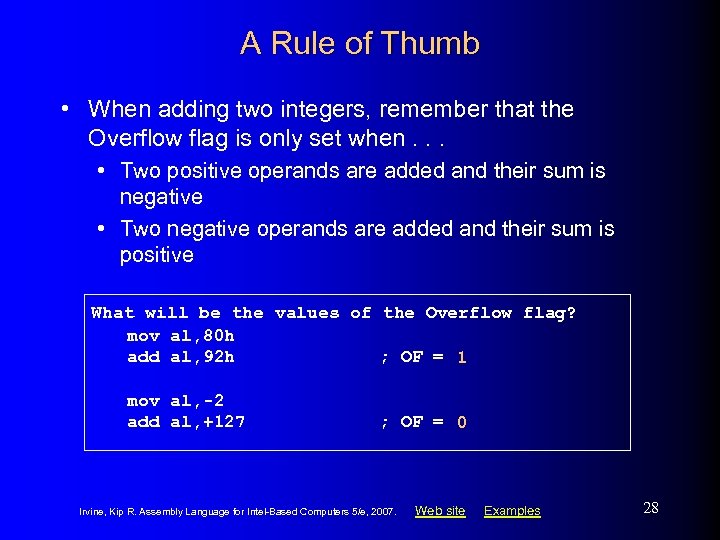

A Rule of Thumb • When adding two integers, remember that the Overflow flag is only set when. . . • Two positive operands are added and their sum is negative • Two negative operands are added and their sum is positive What will be the values of the Overflow flag? mov al, 80 h add al, 92 h ; OF = 1 mov al, -2 add al, +127 ; OF = 0 Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 28

Data-Related Operators and Directives • OFFSET Operator • PTR Operator Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 29

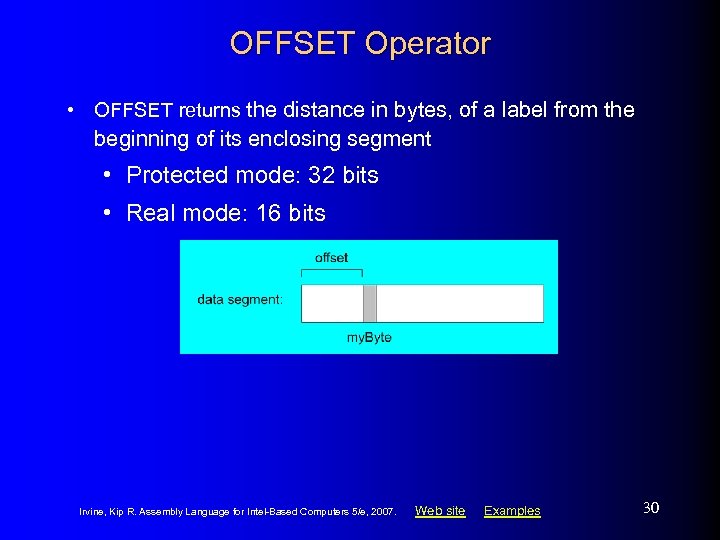

OFFSET Operator • OFFSET returns the distance in bytes, of a label from the beginning of its enclosing segment • Protected mode: 32 bits • Real mode: 16 bits Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 30

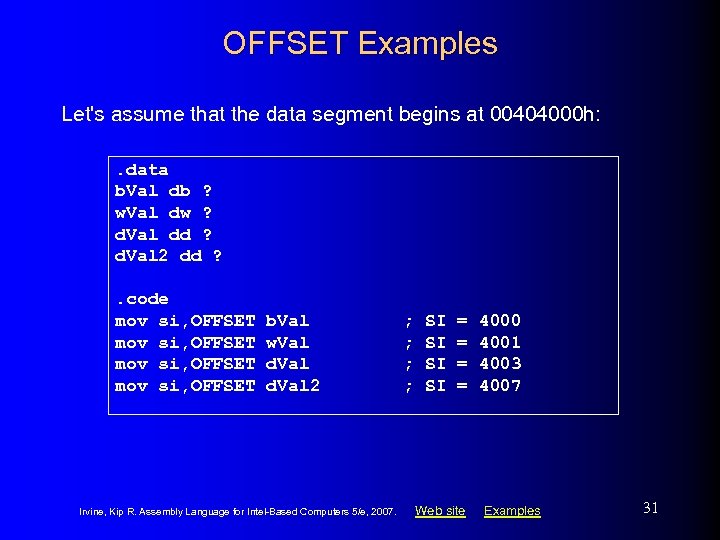

OFFSET Examples Let's assume that the data segment begins at 00404000 h: . data b. Val db ? w. Val dw ? d. Val dd ? d. Val 2 dd ? . code mov si, OFFSET b. Val w. Val d. Val 2 Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. ; ; SI SI = = Web site 4000 4001 4003 4007 Examples 31

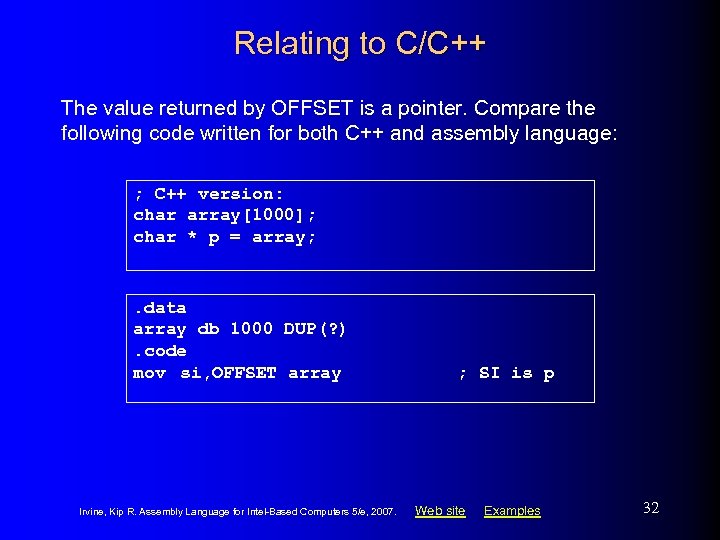

Relating to C/C++ The value returned by OFFSET is a pointer. Compare the following code written for both C++ and assembly language: ; C++ version: char array[1000]; char * p = array; . data array db 1000 DUP(? ). code mov si, OFFSET array Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. ; SI is p Web site Examples 32

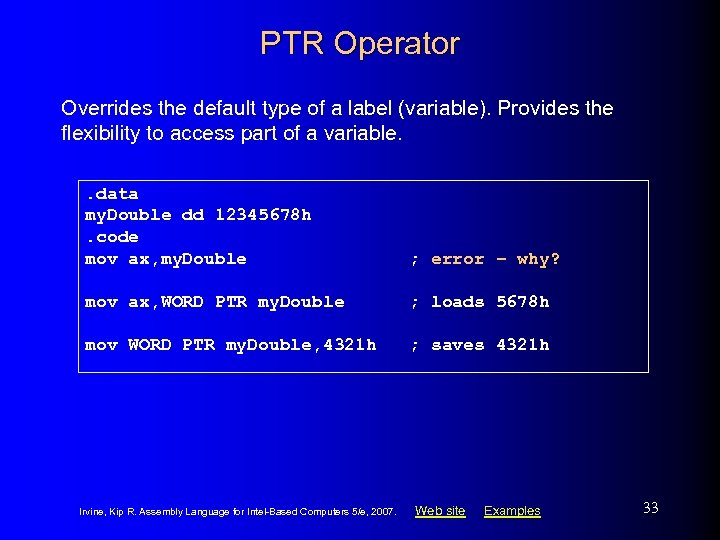

PTR Operator Overrides the default type of a label (variable). Provides the flexibility to access part of a variable. . data my. Double dd 12345678 h. code mov ax, my. Double ; error – why? mov ax, WORD PTR my. Double ; loads 5678 h mov WORD PTR my. Double, 4321 h ; saves 4321 h Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 33

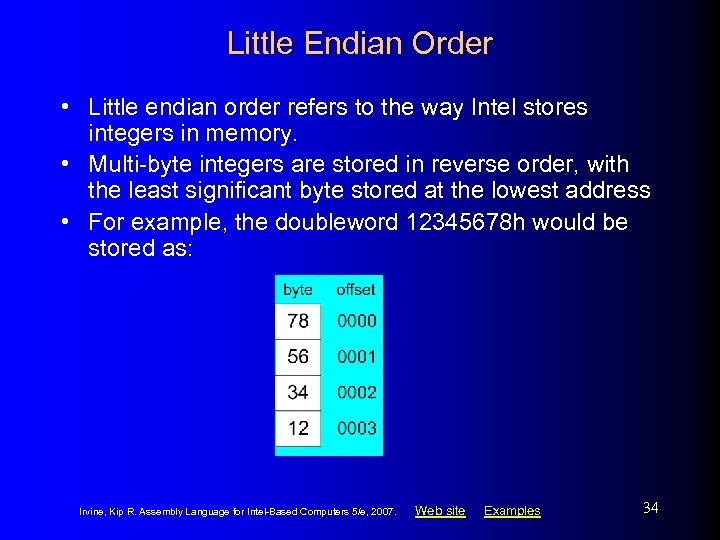

Little Endian Order • Little endian order refers to the way Intel stores integers in memory. • Multi-byte integers are stored in reverse order, with the least significant byte stored at the lowest address • For example, the doubleword 12345678 h would be stored as: Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 34

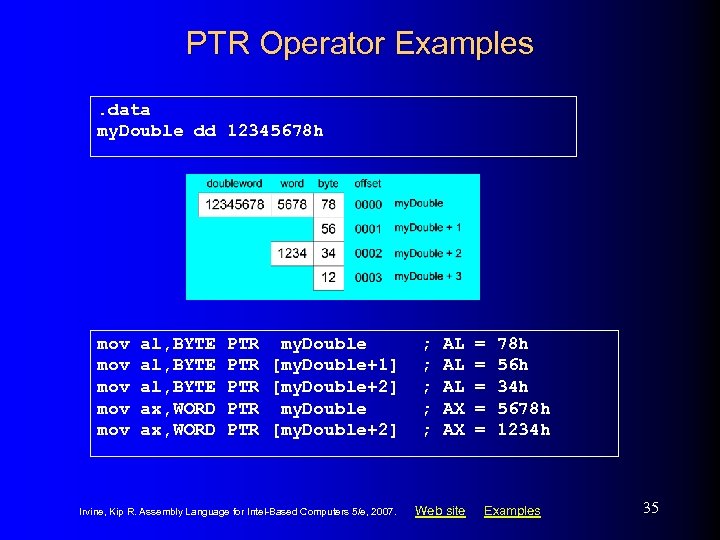

PTR Operator Examples. data my. Double dd 12345678 h mov mov mov al, BYTE ax, WORD PTR my. Double PTR [my. Double+1] PTR [my. Double+2] PTR my. Double PTR [my. Double+2] Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. ; ; ; AL AL AL AX AX Web site = = = 78 h 56 h 34 h 5678 h 1234 h Examples 35

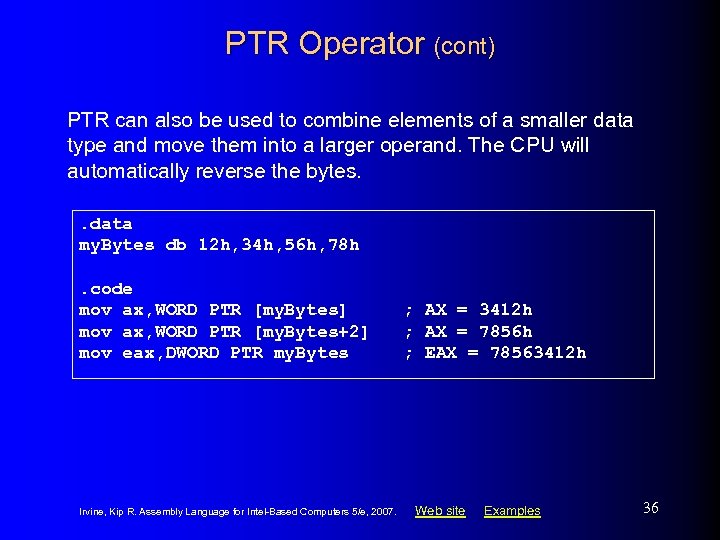

PTR Operator (cont) PTR can also be used to combine elements of a smaller data type and move them into a larger operand. The CPU will automatically reverse the bytes. . data my. Bytes db 12 h, 34 h, 56 h, 78 h. code mov ax, WORD PTR [my. Bytes] mov ax, WORD PTR [my. Bytes+2] mov eax, DWORD PTR my. Bytes Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. ; AX = 3412 h ; AX = 7856 h ; EAX = 78563412 h Web site Examples 36

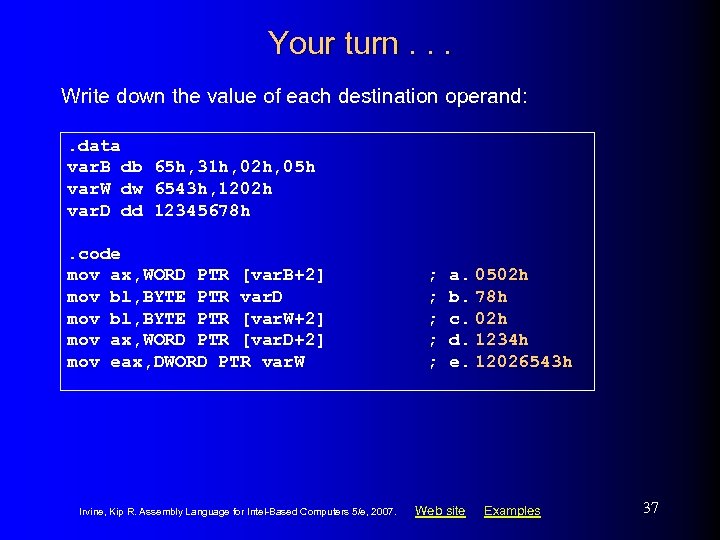

Your turn. . . Write down the value of each destination operand: . data var. B db 65 h, 31 h, 02 h, 05 h var. W dw 6543 h, 1202 h var. D dd 12345678 h. code mov ax, WORD PTR [var. B+2] mov bl, BYTE PTR var. D mov bl, BYTE PTR [var. W+2] mov ax, WORD PTR [var. D+2] mov eax, DWORD PTR var. W Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. ; ; ; a. 0502 h b. 78 h c. 02 h d. 1234 h e. 12026543 h Web site Examples 37

Indirect Addressing • • Indirect Operands Array Sum Example Indexed Operands Pointers Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 38

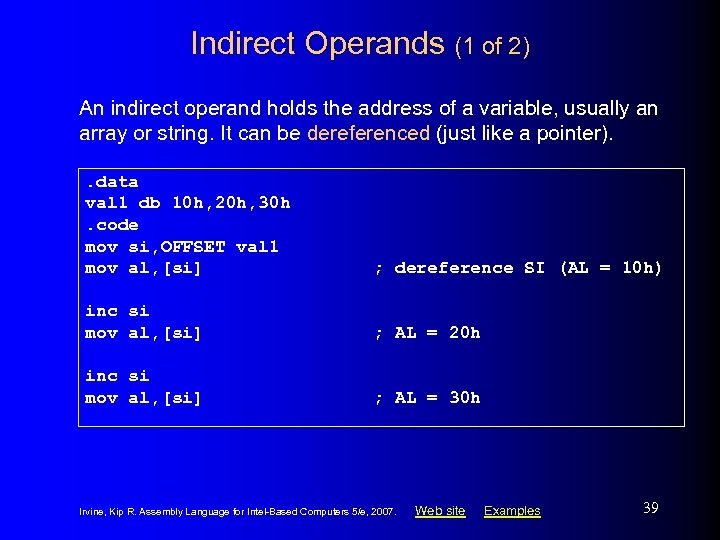

Indirect Operands (1 of 2) An indirect operand holds the address of a variable, usually an array or string. It can be dereferenced (just like a pointer). . data val 1 db 10 h, 20 h, 30 h. code mov si, OFFSET val 1 mov al, [si] ; dereference SI (AL = 10 h) inc si mov al, [si] ; AL = 20 h inc si mov al, [si] ; AL = 30 h Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 39

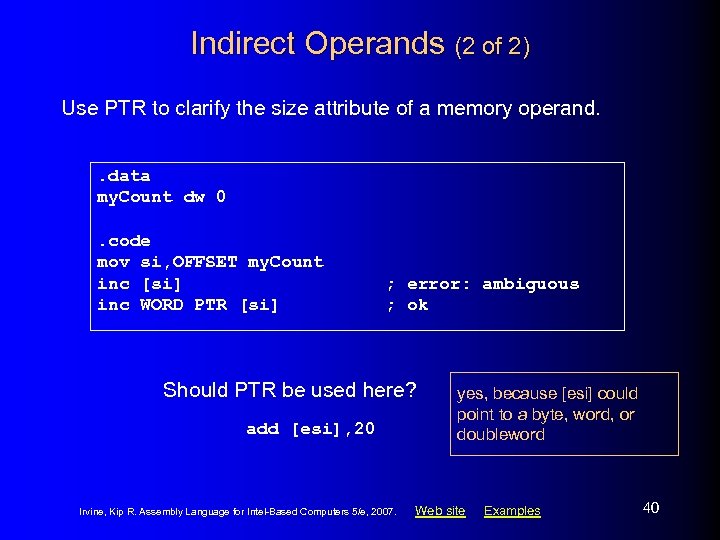

Indirect Operands (2 of 2) Use PTR to clarify the size attribute of a memory operand. . data my. Count dw 0. code mov si, OFFSET my. Count inc [si] inc WORD PTR [si] ; error: ambiguous ; ok Should PTR be used here? add [esi], 20 Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. yes, because [esi] could point to a byte, word, or doubleword Web site Examples 40

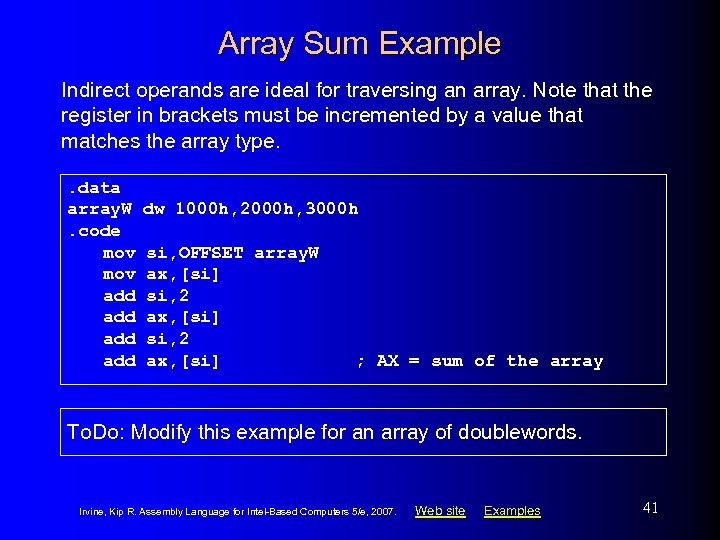

Array Sum Example Indirect operands are ideal for traversing an array. Note that the register in brackets must be incremented by a value that matches the array type. . data array. W. code mov add add dw 1000 h, 2000 h, 3000 h si, OFFSET array. W ax, [si] si, 2 ax, [si] ; AX = sum of the array To. Do: Modify this example for an array of doublewords. Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 41

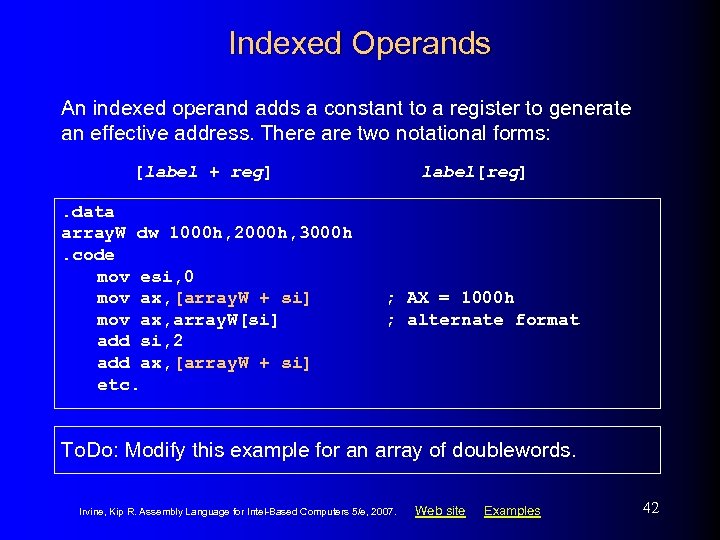

Indexed Operands An indexed operand adds a constant to a register to generate an effective address. There are two notational forms: [label + reg]. data array. W dw 1000 h, 2000 h, 3000 h. code mov esi, 0 mov ax, [array. W + si] mov ax, array. W[si] add si, 2 add ax, [array. W + si] etc. label[reg] ; AX = 1000 h ; alternate format To. Do: Modify this example for an array of doublewords. Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 42

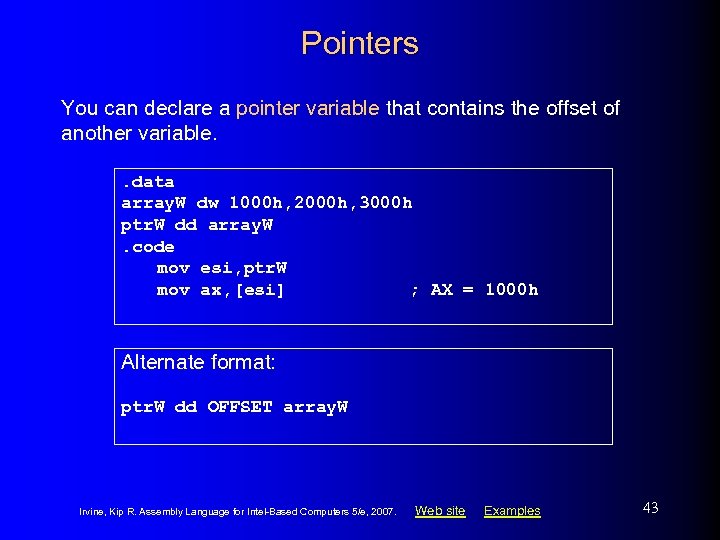

Pointers You can declare a pointer variable that contains the offset of another variable. . data array. W dw 1000 h, 2000 h, 3000 h ptr. W dd array. W. code mov esi, ptr. W mov ax, [esi] ; AX = 1000 h Alternate format: ptr. W dd OFFSET array. W Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 43

JMP and LOOP Instructions • • • JMP Instruction LOOP Example Summing an Integer Array Copying a String Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 44

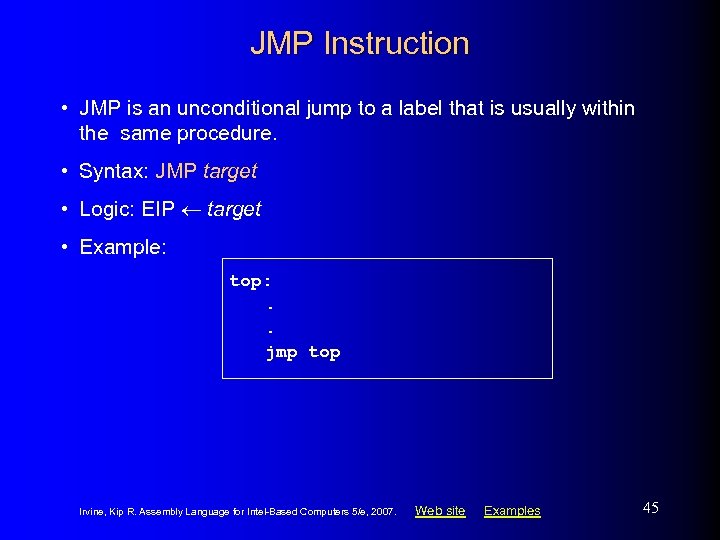

JMP Instruction • JMP is an unconditional jump to a label that is usually within the same procedure. • Syntax: JMP target • Logic: EIP target • Example: top: . . jmp top Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 45

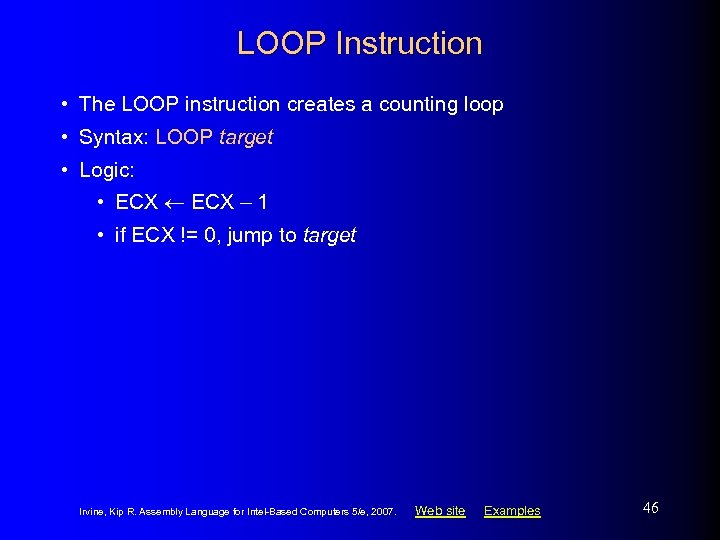

LOOP Instruction • The LOOP instruction creates a counting loop • Syntax: LOOP target • Logic: • ECX – 1 • if ECX != 0, jump to target Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 46

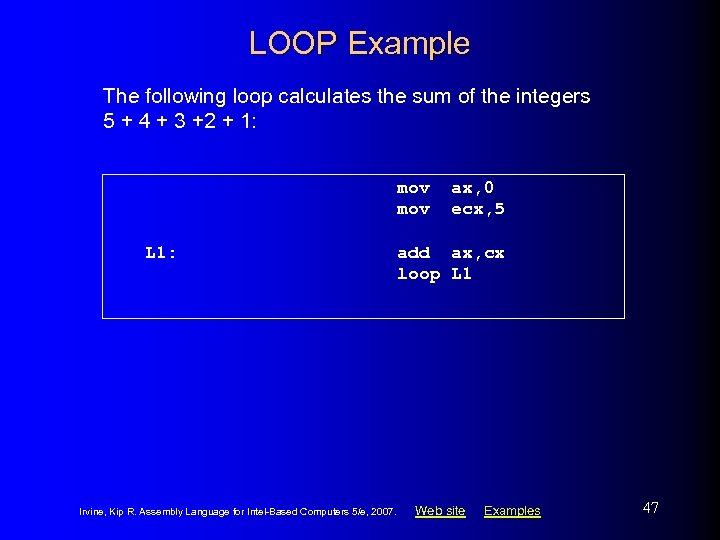

LOOP Example The following loop calculates the sum of the integers 5 + 4 + 3 +2 + 1: mov L 1: Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. ax, 0 ecx, 5 add ax, cx loop L 1 Web site Examples 47

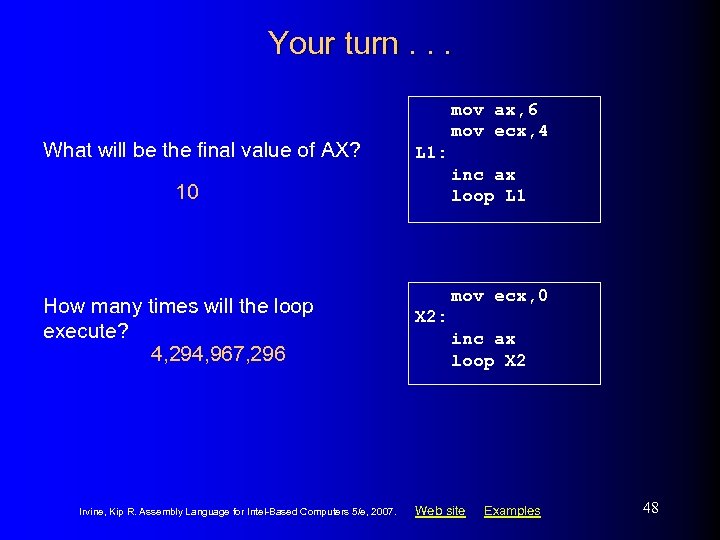

Your turn. . . What will be the final value of AX? mov ax, 6 mov ecx, 4 L 1: inc ax loop L 1 10 How many times will the loop execute? 4, 294, 967, 296 Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. mov ecx, 0 X 2: inc ax loop X 2 Web site Examples 48

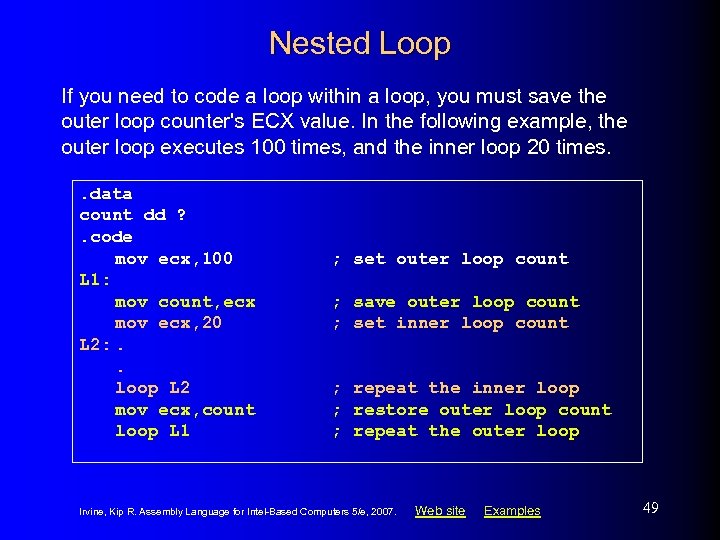

Nested Loop If you need to code a loop within a loop, you must save the outer loop counter's ECX value. In the following example, the outer loop executes 100 times, and the inner loop 20 times. . data count dd ? . code mov ecx, 100 L 1: mov count, ecx mov ecx, 20 L 2: . . loop L 2 mov ecx, count loop L 1 ; set outer loop count ; save outer loop count ; set inner loop count ; repeat the inner loop ; restore outer loop count ; repeat the outer loop Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. Web site Examples 49

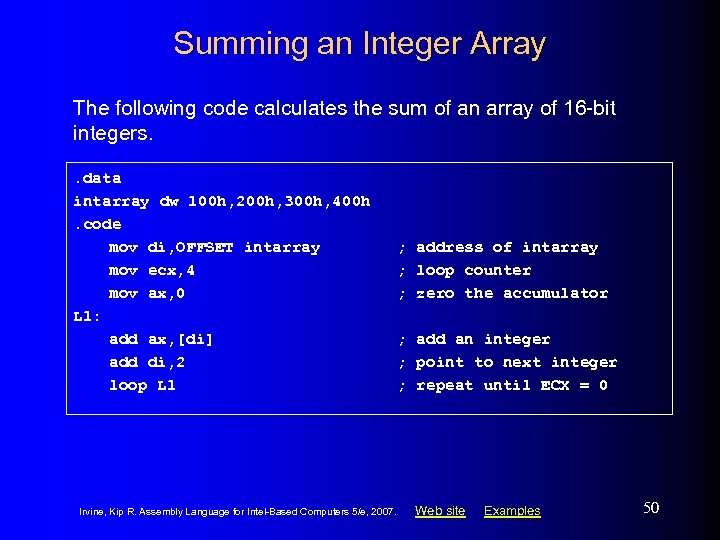

Summing an Integer Array The following code calculates the sum of an array of 16 -bit integers. . data intarray dw 100 h, 200 h, 300 h, 400 h. code mov di, OFFSET intarray mov ecx, 4 mov ax, 0 L 1: add ax, [di] add di, 2 loop L 1 Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. ; address of intarray ; loop counter ; zero the accumulator ; add an integer ; point to next integer ; repeat until ECX = 0 Web site Examples 50

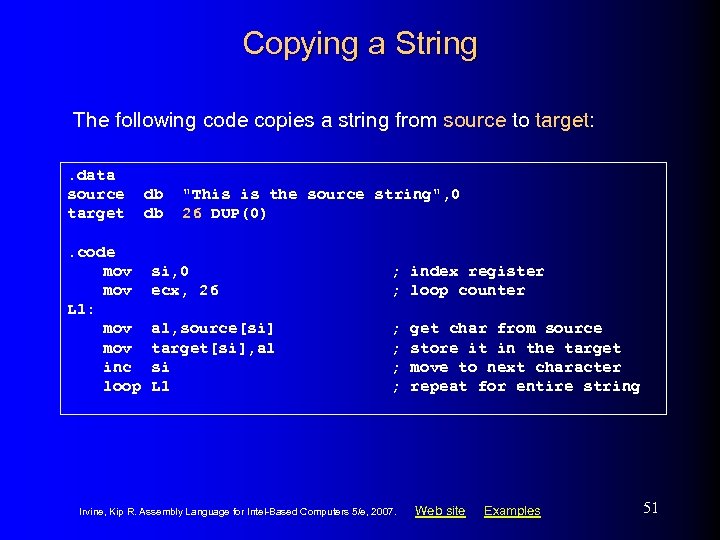

Copying a String The following code copies a string from source to target: . data source target. code mov L 1: mov inc loop db db "This is the source string", 0 26 DUP(0) si, 0 ecx, 26 ; index register ; loop counter al, source[si] target[si], al si L 1 ; ; Irvine, Kip R. Assembly Language for Intel-Based Computers 5/e, 2007. get char from source store it in the target move to next character repeat for entire string Web site Examples 51

e56a22beb1607417098d5b236d52dd63.ppt