L4.Architecture_of_Mesopotamia.pptx

- Количество слайдов: 33

ARCHITECTURE OF MESOPOTAMIA LECTURE 4

ARCHITECTURE OF MESOPOTAMIA LECTURE 4

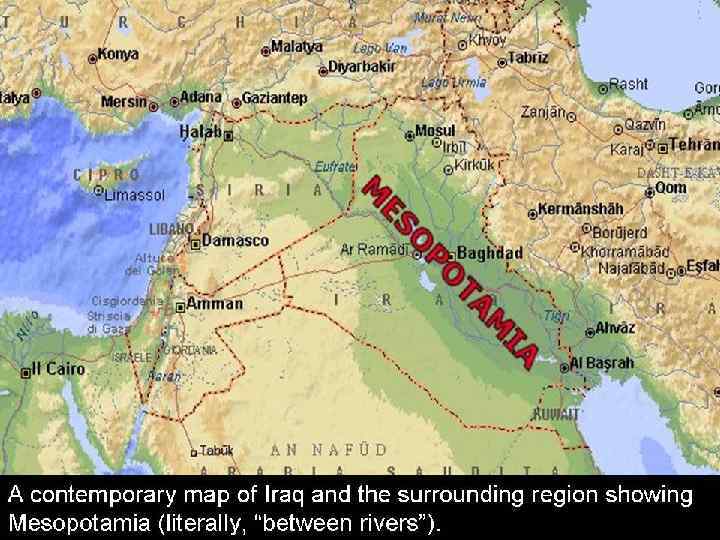

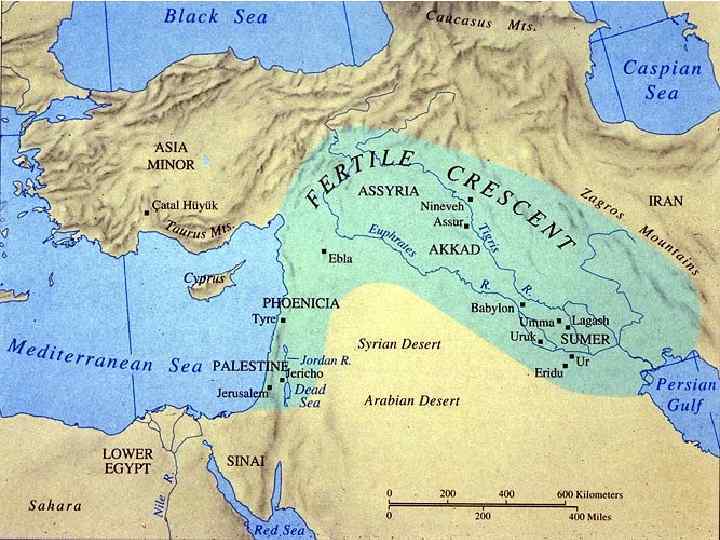

ARCHITECTURE OF MESOPOTAMIA • The architecture of Mesopotamia is the ancient architecture of the region of the Tigris–Euphrates river system • encompassing several distinct cultures • spanning a period from the 10 th millennium BC, when the first permanent structures were built, to the 6 th century BC. • Among the Mesopotamian architectural accomplishments are the development of urban planning, the courtyard house, and ziggurats.

ARCHITECTURE OF MESOPOTAMIA • The architecture of Mesopotamia is the ancient architecture of the region of the Tigris–Euphrates river system • encompassing several distinct cultures • spanning a period from the 10 th millennium BC, when the first permanent structures were built, to the 6 th century BC. • Among the Mesopotamian architectural accomplishments are the development of urban planning, the courtyard house, and ziggurats.

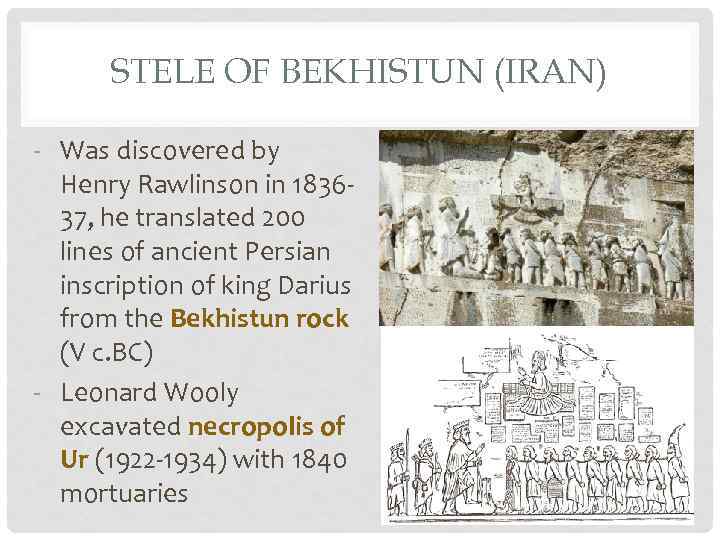

STELE OF BEKHISTUN (IRAN) - Was discovered by Henry Rawlinson in 183637, he translated 200 lines of ancient Persian inscription of king Darius from the Bekhistun rock (V c. BC) - Leonard Wooly excavated necropolis of Ur (1922 -1934) with 1840 mortuaries

STELE OF BEKHISTUN (IRAN) - Was discovered by Henry Rawlinson in 183637, he translated 200 lines of ancient Persian inscription of king Darius from the Bekhistun rock (V c. BC) - Leonard Wooly excavated necropolis of Ur (1922 -1934) with 1840 mortuaries

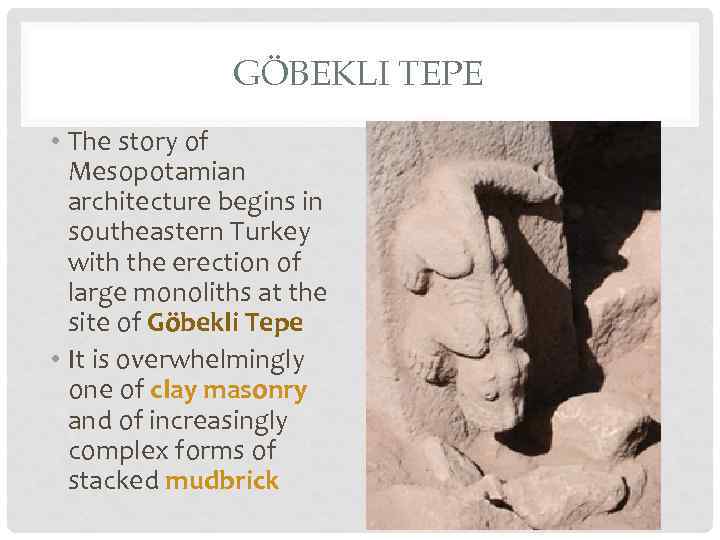

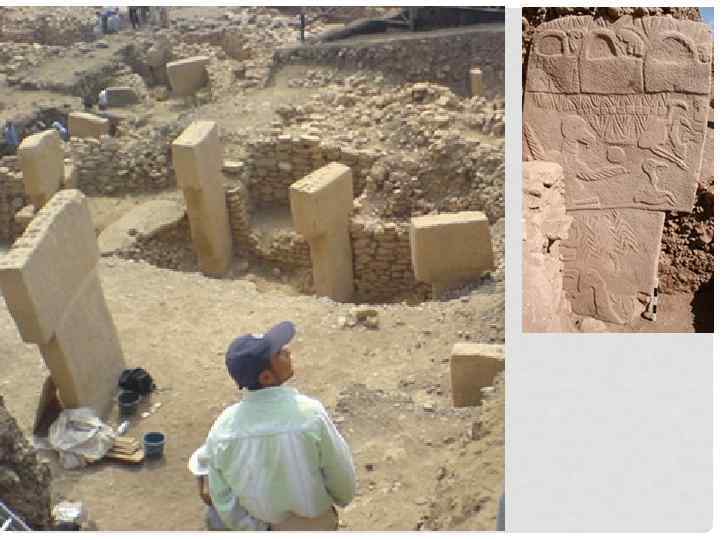

GÖBEKLI TEPE • The story of Mesopotamian architecture begins in southeastern Turkey with the erection of large monoliths at the site of Göbekli Tepe • It is overwhelmingly one of clay masonry and of increasingly complex forms of stacked mudbrick

GÖBEKLI TEPE • The story of Mesopotamian architecture begins in southeastern Turkey with the erection of large monoliths at the site of Göbekli Tepe • It is overwhelmingly one of clay masonry and of increasingly complex forms of stacked mudbrick

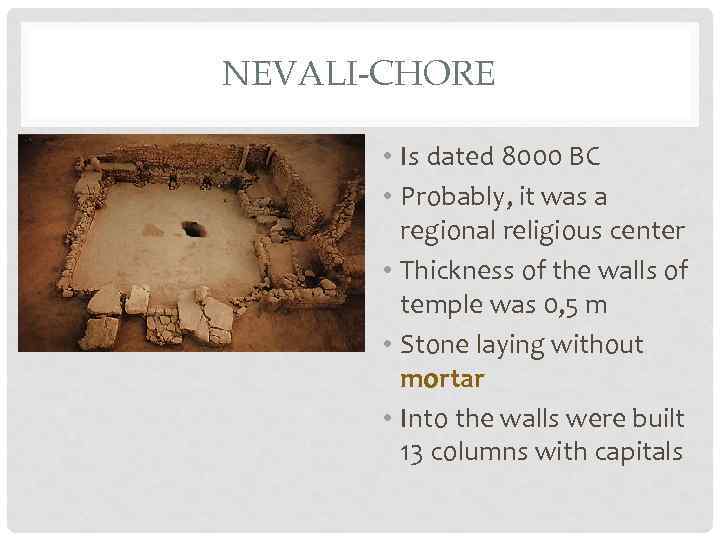

NEVALI-CHORE • Is dated 8000 BC • Probably, it was a regional religious center • Thickness of the walls of temple was 0, 5 m • Stone laying without mortar • Into the walls were built 13 columns with capitals

NEVALI-CHORE • Is dated 8000 BC • Probably, it was a regional religious center • Thickness of the walls of temple was 0, 5 m • Stone laying without mortar • Into the walls were built 13 columns with capitals

MATERIALS • Adobe-brick was preferred over vitreous brick because of its superior thermal properties and lower manufacturing costs. • Red brick was used in small applications involving water, decoration, and monumental construction. • A late innovation was glazed vitreous. Sumerian masonry was usually mortarless although bitumen was sometimes used. Brick styles, which varied greatly over time, are categorized by period. • Specially prized were imported building materials such as cedar from Lebanon, diorite from Arabia, and lapis lazuli from India

MATERIALS • Adobe-brick was preferred over vitreous brick because of its superior thermal properties and lower manufacturing costs. • Red brick was used in small applications involving water, decoration, and monumental construction. • A late innovation was glazed vitreous. Sumerian masonry was usually mortarless although bitumen was sometimes used. Brick styles, which varied greatly over time, are categorized by period. • Specially prized were imported building materials such as cedar from Lebanon, diorite from Arabia, and lapis lazuli from India

URBAN DEVELOPMENT • The typical city divided space into residential, mixed use, commercial, and civic spaces. • The residential areas were grouped by profession. • At the core of the city was a high temple complex always sited slightly off of the geographical center. • This high temple usually predated the founding of the city and was the nucleus around which the urban form grew. • The districts adjacent to gates had a special religious and economic function

URBAN DEVELOPMENT • The typical city divided space into residential, mixed use, commercial, and civic spaces. • The residential areas were grouped by profession. • At the core of the city was a high temple complex always sited slightly off of the geographical center. • This high temple usually predated the founding of the city and was the nucleus around which the urban form grew. • The districts adjacent to gates had a special religious and economic function

URBAN DEVELOPMENT • The city always included a belt of irrigated agricultural land including small hamlets. • A network of roads and canals • The transportation network was organized in three tiers: wide processional streets (Akkadian: sūqu ilāni u šarri), public through streets (Akkadian: sūqu nišī), and private blind alleys (Akkadian: mūṣû). • The public streets that defined a block varied little over time while the blind-alleys were much more fluid. • The current estimate is 10% of the city area was streets and 90% buildings. The canals were more important than roads for transportation

URBAN DEVELOPMENT • The city always included a belt of irrigated agricultural land including small hamlets. • A network of roads and canals • The transportation network was organized in three tiers: wide processional streets (Akkadian: sūqu ilāni u šarri), public through streets (Akkadian: sūqu nišī), and private blind alleys (Akkadian: mūṣû). • The public streets that defined a block varied little over time while the blind-alleys were much more fluid. • The current estimate is 10% of the city area was streets and 90% buildings. The canals were more important than roads for transportation

DWELLINGS • House called e (Sumerian: e; Akkadian: bītu) faced inward toward an open courtyard which provided a cooling effect by creating convection currents. • This courtyard called tarbaṣu (Akkadian) was the primary organizing feature of the house, all the rooms opened into it. • Movement between the house and street required a 90° turn through a small antechamber. • The Sumerians had a strict division of public and private spaces. The typical size for a Sumerian house was 90 m 2

DWELLINGS • House called e (Sumerian: e; Akkadian: bītu) faced inward toward an open courtyard which provided a cooling effect by creating convection currents. • This courtyard called tarbaṣu (Akkadian) was the primary organizing feature of the house, all the rooms opened into it. • Movement between the house and street required a 90° turn through a small antechamber. • The Sumerians had a strict division of public and private spaces. The typical size for a Sumerian house was 90 m 2

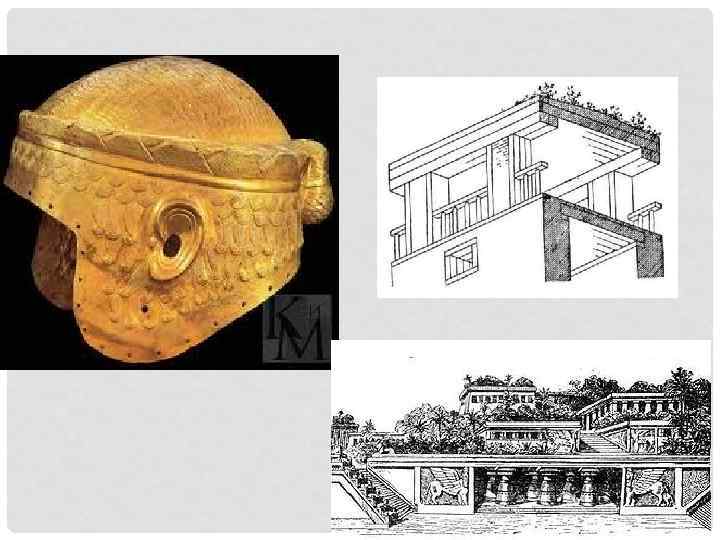

PALACES • Earliest known examples are from the Diyala River valley sites such as Khafajah and Tell Asmar. • These III millennium BC palaces functioned as large-scale socio-economic institutions, and therefore, along with residential and private functions, they housed craftsmen workshops, food storehouses, ceremonial courtyards, and are often associated with shrines. • “Giparu" (or Gig-Par-Ku in Sumerian) at Ur where the Moon god Nanna's priestesses resided was a major complex with multiple courtyards, a number of sanctuaries, burial chambers for dead priestesses, and a ceremonial banquet hall.

PALACES • Earliest known examples are from the Diyala River valley sites such as Khafajah and Tell Asmar. • These III millennium BC palaces functioned as large-scale socio-economic institutions, and therefore, along with residential and private functions, they housed craftsmen workshops, food storehouses, ceremonial courtyards, and are often associated with shrines. • “Giparu" (or Gig-Par-Ku in Sumerian) at Ur where the Moon god Nanna's priestesses resided was a major complex with multiple courtyards, a number of sanctuaries, burial chambers for dead priestesses, and a ceremonial banquet hall.

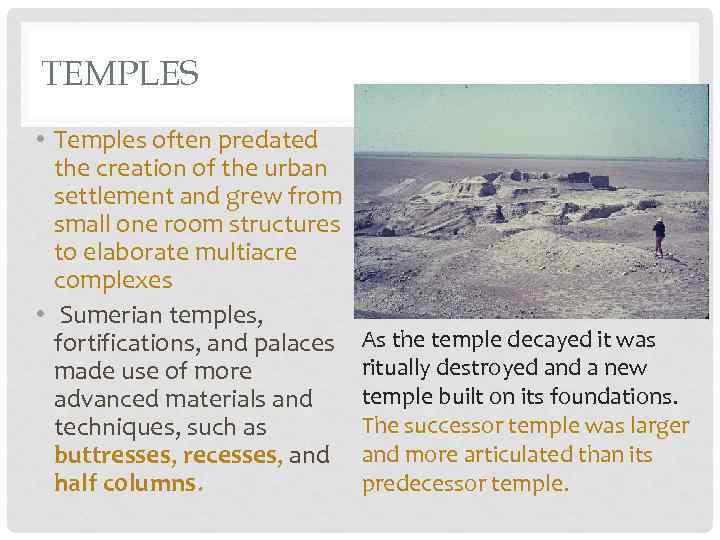

TEMPLES • Temples often predated the creation of the urban settlement and grew from small one room structures to elaborate multiacre complexes • Sumerian temples, fortifications, and palaces made use of more advanced materials and techniques, such as buttresses, recesses, and half columns. As the temple decayed it was ritually destroyed and a new temple built on its foundations. The successor temple was larger and more articulated than its predecessor temple.

TEMPLES • Temples often predated the creation of the urban settlement and grew from small one room structures to elaborate multiacre complexes • Sumerian temples, fortifications, and palaces made use of more advanced materials and techniques, such as buttresses, recesses, and half columns. As the temple decayed it was ritually destroyed and a new temple built on its foundations. The successor temple was larger and more articulated than its predecessor temple.

URUK (6000 BC) • Temples and palaces from the Early Dynastic period sites in the Diyala River valley such as Khafajah and Tell Asmar, the Third Dynasty of Ur remains at Nippur (Sanctuary of Enlil) and Ur (Sanctuary of Nanna), Middle Bronze Age remains at Syrian-Turkish sites of Ebla, Mari, Alalakh, Aleppo and Kultepe, Late Bronze Age palaces at Bogazkoy (Hattusha), Ugarit, Ashur and Nuzi, Iron Age palaces and temples at Assyrian (Kalhu/Nimrud, Khorsabad, Nineveh), Babylonian (Babylon), Urartian (Tushpa/Van Kalesi, Cavustepe, Ayanis, Armavir, Erebuni, Bastam) and Neo-Hittite sites (Karkamis, Tell Halaf, Karatepe).

URUK (6000 BC) • Temples and palaces from the Early Dynastic period sites in the Diyala River valley such as Khafajah and Tell Asmar, the Third Dynasty of Ur remains at Nippur (Sanctuary of Enlil) and Ur (Sanctuary of Nanna), Middle Bronze Age remains at Syrian-Turkish sites of Ebla, Mari, Alalakh, Aleppo and Kultepe, Late Bronze Age palaces at Bogazkoy (Hattusha), Ugarit, Ashur and Nuzi, Iron Age palaces and temples at Assyrian (Kalhu/Nimrud, Khorsabad, Nineveh), Babylonian (Babylon), Urartian (Tushpa/Van Kalesi, Cavustepe, Ayanis, Armavir, Erebuni, Bastam) and Neo-Hittite sites (Karkamis, Tell Halaf, Karatepe).

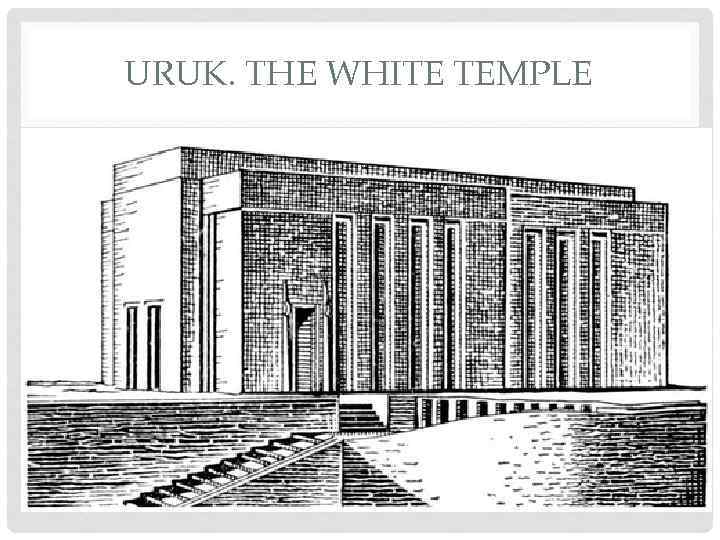

URUK. THE WHITE TEMPLE

URUK. THE WHITE TEMPLE

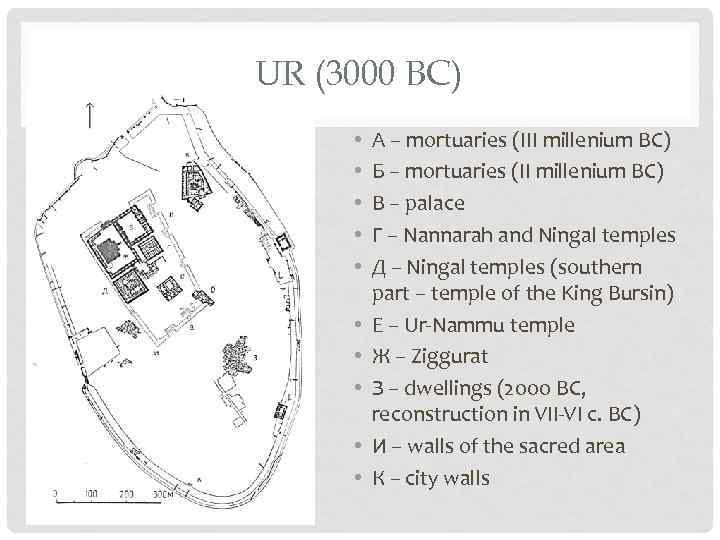

UR (3000 BC) • • • А – mortuaries (III millenium BC) Б – mortuaries (II millenium BC) В – palace Г – Nannarah and Ningal temples Д – Ningal temples (southern part – temple of the King Bursin) Е – Ur-Nammu temple Ж – Ziggurat З – dwellings (2000 BC, reconstruction in VII-VI c. BC) И – walls of the sacred area К – city walls

UR (3000 BC) • • • А – mortuaries (III millenium BC) Б – mortuaries (II millenium BC) В – palace Г – Nannarah and Ningal temples Д – Ningal temples (southern part – temple of the King Bursin) Е – Ur-Nammu temple Ж – Ziggurat З – dwellings (2000 BC, reconstruction in VII-VI c. BC) И – walls of the sacred area К – city walls

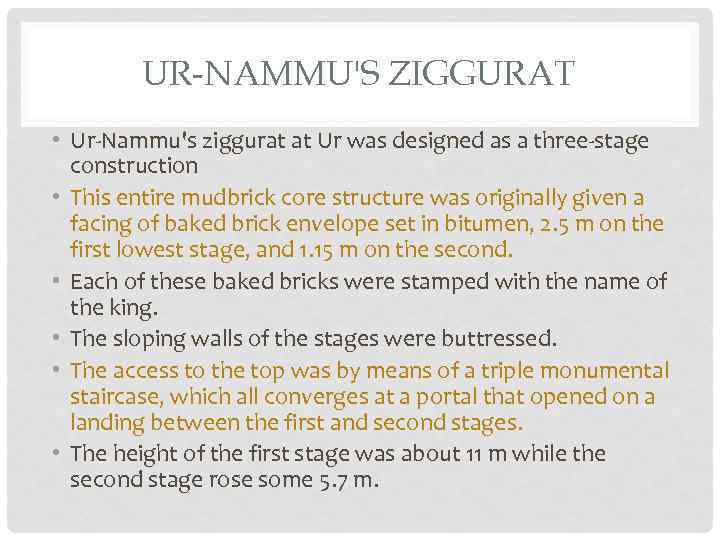

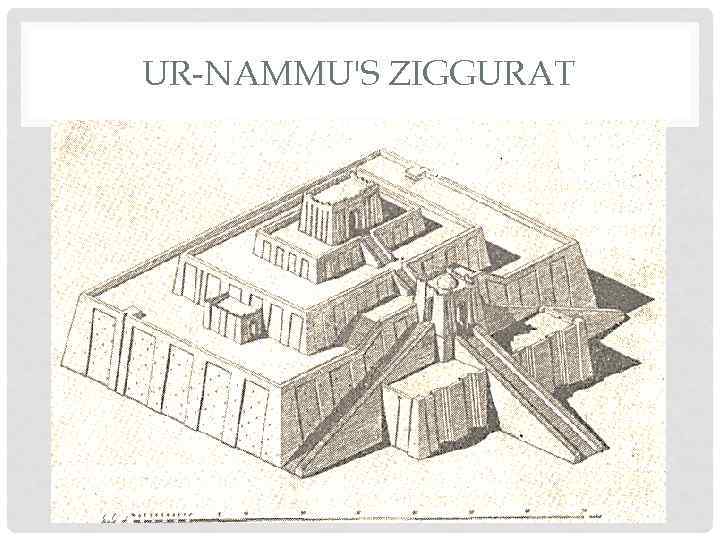

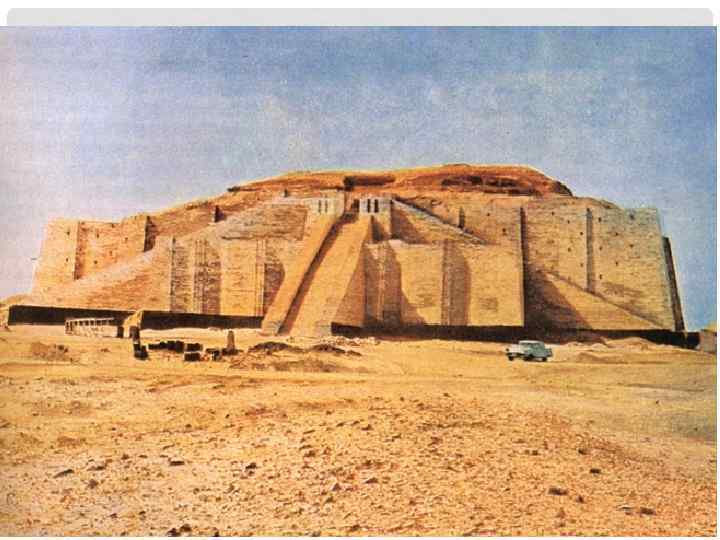

UR-NAMMU'S ZIGGURAT • Ur-Nammu's ziggurat at Ur was designed as a three-stage construction • This entire mudbrick core structure was originally given a facing of baked brick envelope set in bitumen, 2. 5 m on the first lowest stage, and 1. 15 m on the second. • Each of these baked bricks were stamped with the name of the king. • The sloping walls of the stages were buttressed. • The access to the top was by means of a triple monumental staircase, which all converges at a portal that opened on a landing between the first and second stages. • The height of the first stage was about 11 m while the second stage rose some 5. 7 m.

UR-NAMMU'S ZIGGURAT • Ur-Nammu's ziggurat at Ur was designed as a three-stage construction • This entire mudbrick core structure was originally given a facing of baked brick envelope set in bitumen, 2. 5 m on the first lowest stage, and 1. 15 m on the second. • Each of these baked bricks were stamped with the name of the king. • The sloping walls of the stages were buttressed. • The access to the top was by means of a triple monumental staircase, which all converges at a portal that opened on a landing between the first and second stages. • The height of the first stage was about 11 m while the second stage rose some 5. 7 m.

UR-NAMMU'S ZIGGURAT

UR-NAMMU'S ZIGGURAT

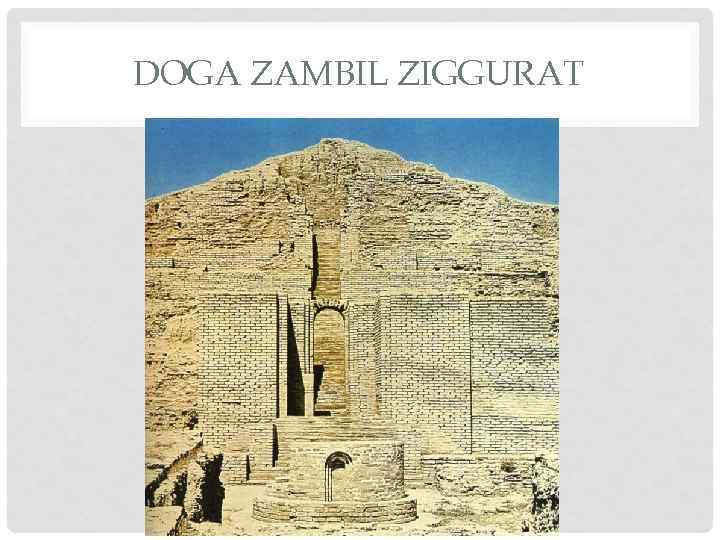

DOGA ZAMBIL ZIGGURAT

DOGA ZAMBIL ZIGGURAT

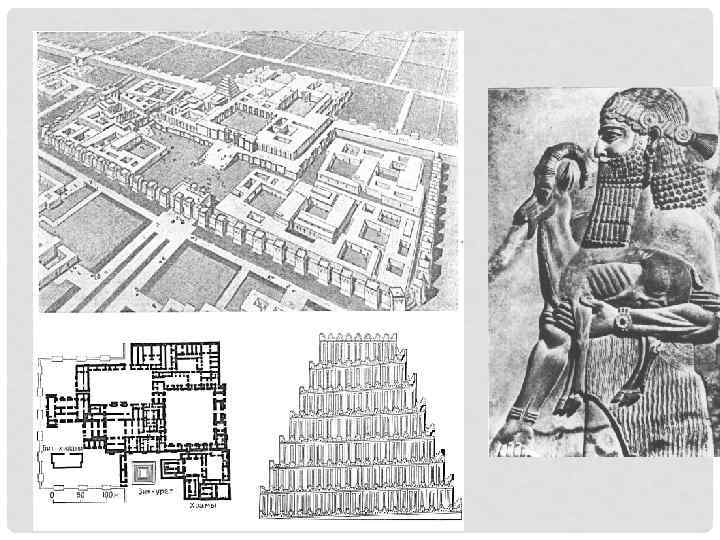

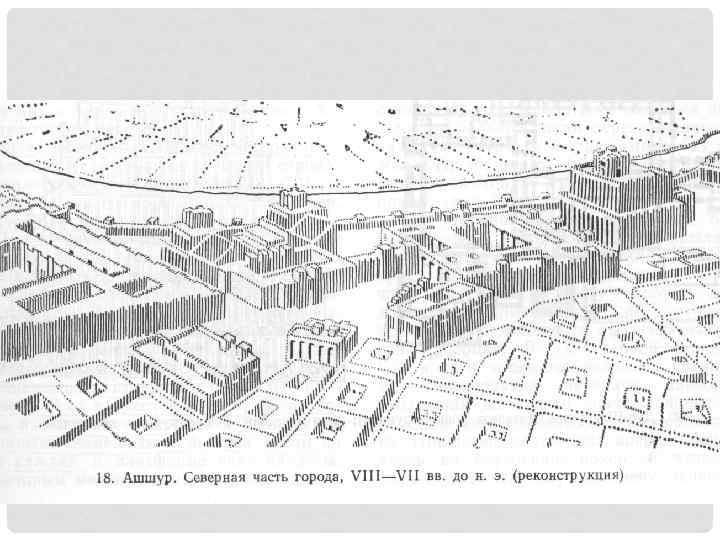

ASSIRIAN ARCHITECTURE • Rectangular plans • Eastern architects used this outline almost invariably, and upon it reared some of the most lovely and varied forms ever devised. • They gather over the angles by graceful curves, and on the basis of an ordinary square hall carry up a minaret or a dome, an octagon or a circle. • That this was sometimes done in Assyria is shown by the sculptures. • Slabs from Kouyunjik show domes of varied form, and tower-like structures, each rising from a square base.

ASSIRIAN ARCHITECTURE • Rectangular plans • Eastern architects used this outline almost invariably, and upon it reared some of the most lovely and varied forms ever devised. • They gather over the angles by graceful curves, and on the basis of an ordinary square hall carry up a minaret or a dome, an octagon or a circle. • That this was sometimes done in Assyria is shown by the sculptures. • Slabs from Kouyunjik show domes of varied form, and tower-like structures, each rising from a square base.

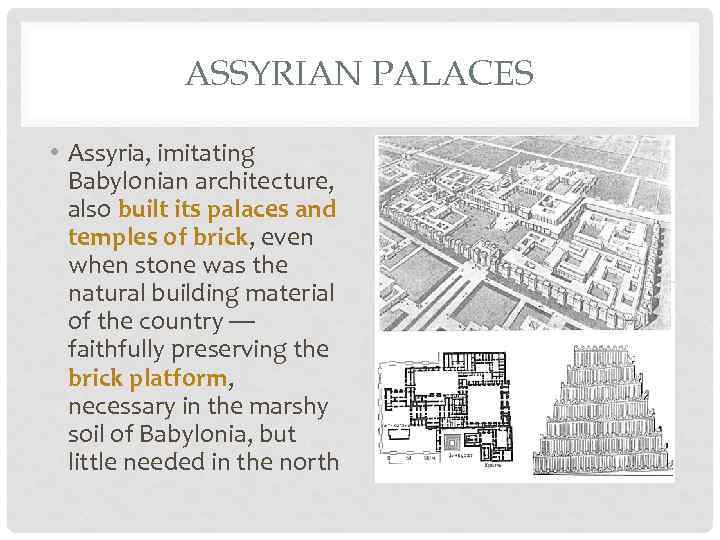

ASSYRIAN PALACES • Assyria, imitating Babylonian architecture, also built its palaces and temples of brick, even when stone was the natural building material of the country — faithfully preserving the brick platform, necessary in the marshy soil of Babylonia, but little needed in the north

ASSYRIAN PALACES • Assyria, imitating Babylonian architecture, also built its palaces and temples of brick, even when stone was the natural building material of the country — faithfully preserving the brick platform, necessary in the marshy soil of Babylonia, but little needed in the north

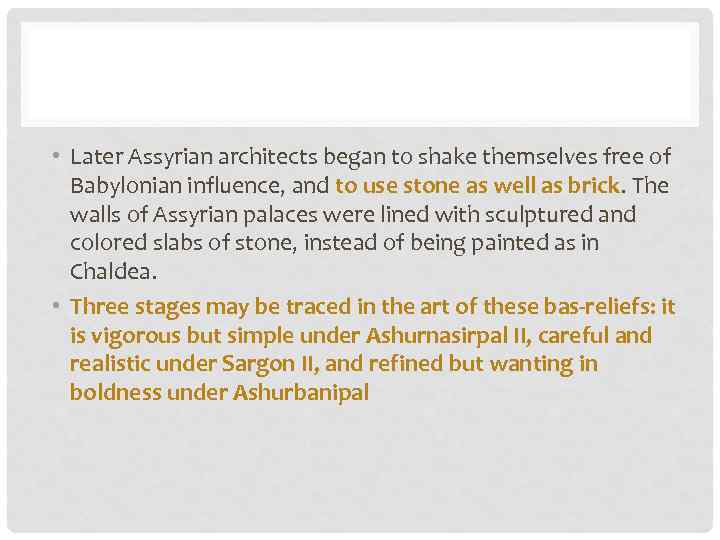

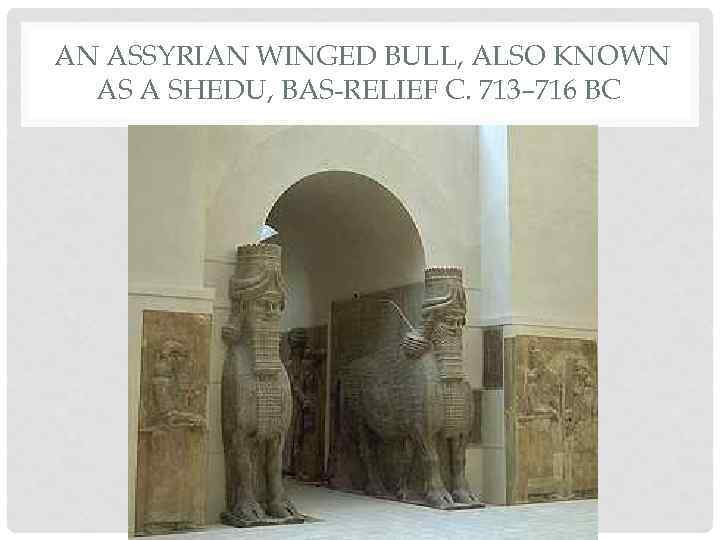

• Later Assyrian architects began to shake themselves free of Babylonian influence, and to use stone as well as brick. The walls of Assyrian palaces were lined with sculptured and colored slabs of stone, instead of being painted as in Chaldea. • Three stages may be traced in the art of these bas-reliefs: it is vigorous but simple under Ashurnasirpal II, careful and realistic under Sargon II, and refined but wanting in boldness under Ashurbanipal

• Later Assyrian architects began to shake themselves free of Babylonian influence, and to use stone as well as brick. The walls of Assyrian palaces were lined with sculptured and colored slabs of stone, instead of being painted as in Chaldea. • Three stages may be traced in the art of these bas-reliefs: it is vigorous but simple under Ashurnasirpal II, careful and realistic under Sargon II, and refined but wanting in boldness under Ashurbanipal

AN ASSYRIAN WINGED BULL, ALSO KNOWN AS A SHEDU, BAS-RELIEF C. 713– 716 BC

AN ASSYRIAN WINGED BULL, ALSO KNOWN AS A SHEDU, BAS-RELIEF C. 713– 716 BC

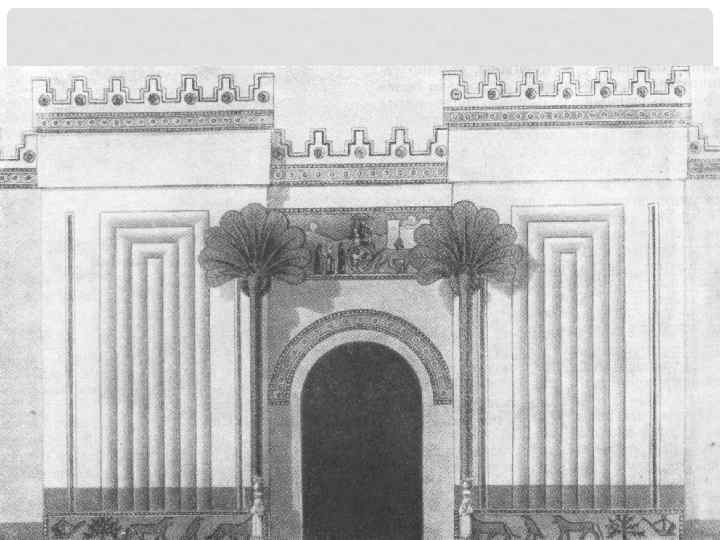

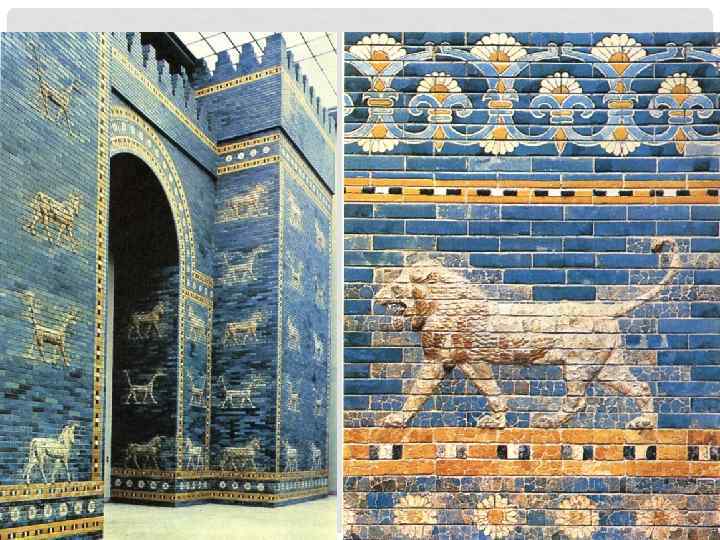

BABYLONIAN TEMPLES • Babylonian temples are massive structures of crude brick, supported by buttresses, the rain being carried off by drains. • The use of brick led to the early development of the pilaster and column, and of frescoes and enamelled tiles. • The walls were brilliantly colored, and sometimes plated with zinc or gold, as well as with tiles. • Painted terra-cotta cones for torches were also embedded in the plaster.

BABYLONIAN TEMPLES • Babylonian temples are massive structures of crude brick, supported by buttresses, the rain being carried off by drains. • The use of brick led to the early development of the pilaster and column, and of frescoes and enamelled tiles. • The walls were brilliantly colored, and sometimes plated with zinc or gold, as well as with tiles. • Painted terra-cotta cones for torches were also embedded in the plaster.

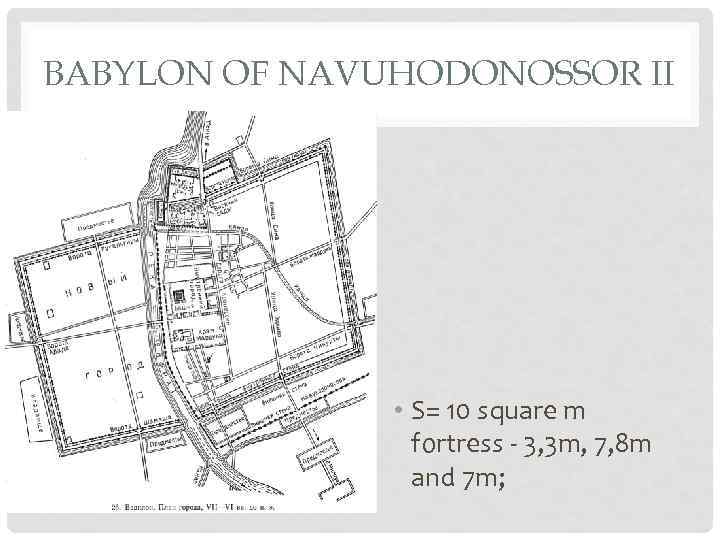

BABYLON OF NAVUHODONOSSOR II • S= 10 square m fortress - 3, 3 m, 7, 8 m and 7 m;

BABYLON OF NAVUHODONOSSOR II • S= 10 square m fortress - 3, 3 m, 7, 8 m and 7 m;

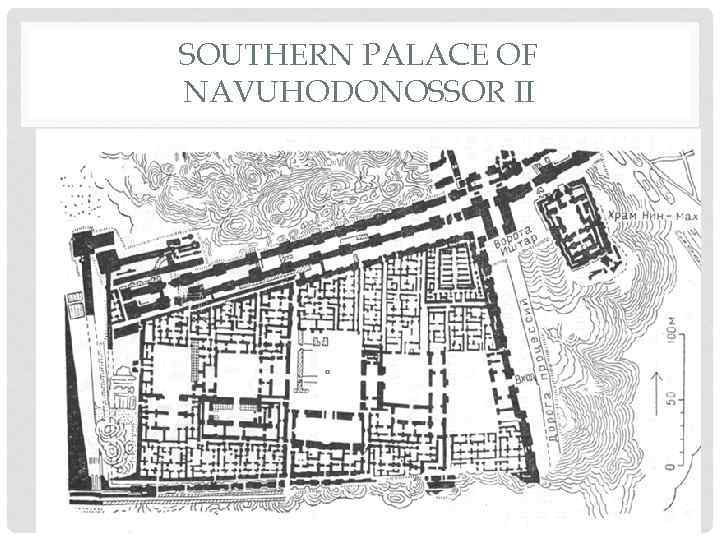

SOUTHERN PALACE OF NAVUHODONOSSOR II

SOUTHERN PALACE OF NAVUHODONOSSOR II