4fad1060b83afcb08fb483559034732a.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 33

Applying Concepts from Cognitive Linguistics to Your Conlang

Applying Concepts from Cognitive Linguistics to Your Conlang

Overview • What this presentation will cover – Why you should know about cognitive linguistics – Specific concepts with implications for conlanging: • What this presentation will not cover – Detailed introduction to cognitive linguistics theory – Aspects of cognitive linguistics not immediately applicable to conlanging • History & Basic Premises of Cognitive Linguistics available in handout

Overview • What this presentation will cover – Why you should know about cognitive linguistics – Specific concepts with implications for conlanging: • What this presentation will not cover – Detailed introduction to cognitive linguistics theory – Aspects of cognitive linguistics not immediately applicable to conlanging • History & Basic Premises of Cognitive Linguistics available in handout

Why You Should Know About It • Obtain deeper understanding of sub-conscious and semi-conscious structures of language • Better ability to avoid inadvertently creating language structures which covertly parallel English (or your native language’s) structures • Opens up a whole new level of creativity in conlang design So, let’s explore some cognitive linguistics…

Why You Should Know About It • Obtain deeper understanding of sub-conscious and semi-conscious structures of language • Better ability to avoid inadvertently creating language structures which covertly parallel English (or your native language’s) structures • Opens up a whole new level of creativity in conlang design So, let’s explore some cognitive linguistics…

Spatial Conceptualization • Through sensory perception, bodily movement, and tactile interaction, infants learn to understand spatial relationships • This pre-linguistic, fundamental knowledge of space, motion, and the senses becomes the foundation for structuring and understanding more abstract conceptual domains • Spatial relationships are understood in terms of landmarks, trajectors, and image schemas

Spatial Conceptualization • Through sensory perception, bodily movement, and tactile interaction, infants learn to understand spatial relationships • This pre-linguistic, fundamental knowledge of space, motion, and the senses becomes the foundation for structuring and understanding more abstract conceptual domains • Spatial relationships are understood in terms of landmarks, trajectors, and image schemas

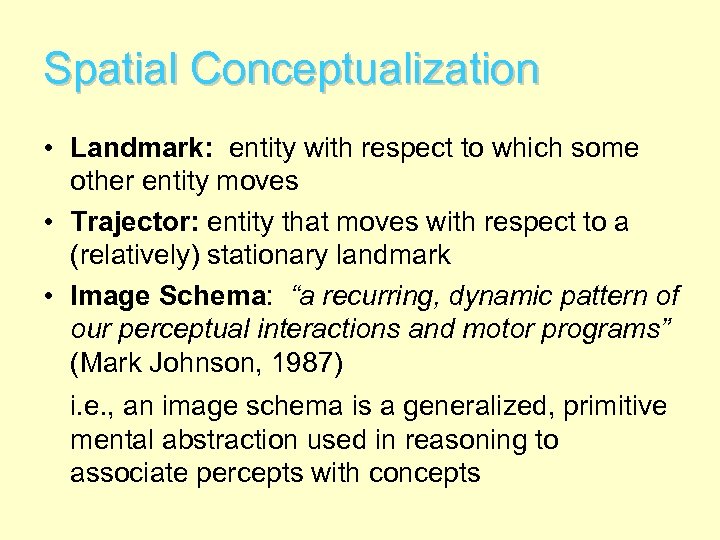

Spatial Conceptualization • Landmark: entity with respect to which some other entity moves • Trajector: entity that moves with respect to a (relatively) stationary landmark • Image Schema: “a recurring, dynamic pattern of our perceptual interactions and motor programs” (Mark Johnson, 1987) i. e. , an image schema is a generalized, primitive mental abstraction used in reasoning to associate percepts with concepts

Spatial Conceptualization • Landmark: entity with respect to which some other entity moves • Trajector: entity that moves with respect to a (relatively) stationary landmark • Image Schema: “a recurring, dynamic pattern of our perceptual interactions and motor programs” (Mark Johnson, 1987) i. e. , an image schema is a generalized, primitive mental abstraction used in reasoning to associate percepts with concepts

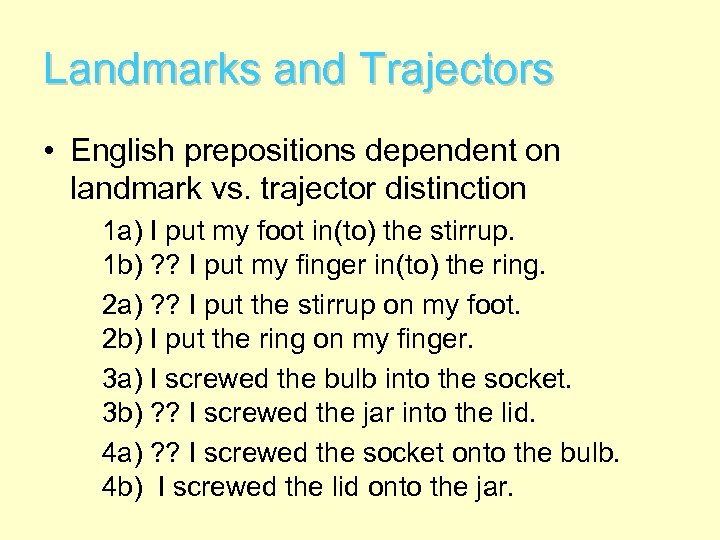

Landmarks and Trajectors • English prepositions dependent on landmark vs. trajector distinction 1 a) I put my foot in(to) the stirrup. 1 b) ? ? I put my finger in(to) the ring. 2 a) ? ? I put the stirrup on my foot. 2 b) I put the ring on my finger. 3 a) I screwed the bulb into the socket. 3 b) ? ? I screwed the jar into the lid. 4 a) ? ? I screwed the socket onto the bulb. 4 b) I screwed the lid onto the jar.

Landmarks and Trajectors • English prepositions dependent on landmark vs. trajector distinction 1 a) I put my foot in(to) the stirrup. 1 b) ? ? I put my finger in(to) the ring. 2 a) ? ? I put the stirrup on my foot. 2 b) I put the ring on my finger. 3 a) I screwed the bulb into the socket. 3 b) ? ? I screwed the jar into the lid. 4 a) ? ? I screwed the socket onto the bulb. 4 b) I screwed the lid onto the jar.

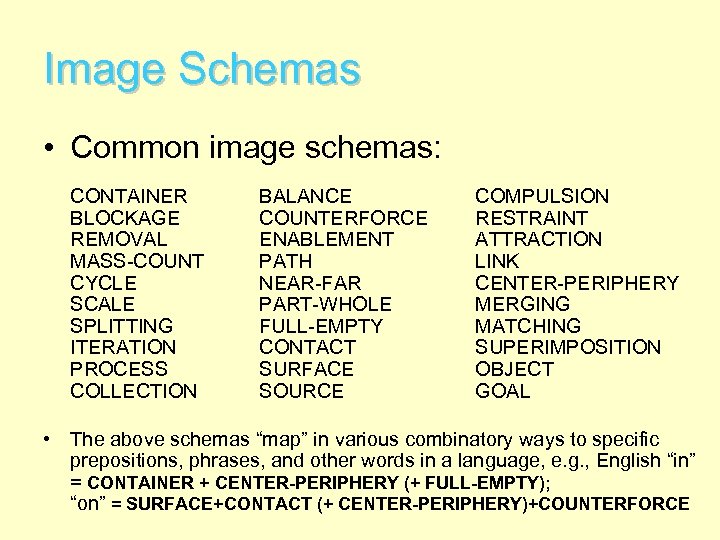

Image Schemas • Common image schemas: CONTAINER BLOCKAGE REMOVAL MASS-COUNT CYCLE SCALE SPLITTING ITERATION PROCESS COLLECTION BALANCE COUNTERFORCE ENABLEMENT PATH NEAR-FAR PART-WHOLE FULL-EMPTY CONTACT SURFACE SOURCE COMPULSION RESTRAINT ATTRACTION LINK CENTER-PERIPHERY MERGING MATCHING SUPERIMPOSITION OBJECT GOAL • The above schemas “map” in various combinatory ways to specific prepositions, phrases, and other words in a language, e. g. , English “in” = CONTAINER + CENTER-PERIPHERY (+ FULL-EMPTY); “on” = SURFACE+CONTACT (+ CENTER-PERIPHERY)+COUNTERFORCE

Image Schemas • Common image schemas: CONTAINER BLOCKAGE REMOVAL MASS-COUNT CYCLE SCALE SPLITTING ITERATION PROCESS COLLECTION BALANCE COUNTERFORCE ENABLEMENT PATH NEAR-FAR PART-WHOLE FULL-EMPTY CONTACT SURFACE SOURCE COMPULSION RESTRAINT ATTRACTION LINK CENTER-PERIPHERY MERGING MATCHING SUPERIMPOSITION OBJECT GOAL • The above schemas “map” in various combinatory ways to specific prepositions, phrases, and other words in a language, e. g. , English “in” = CONTAINER + CENTER-PERIPHERY (+ FULL-EMPTY); “on” = SURFACE+CONTACT (+ CENTER-PERIPHERY)+COUNTERFORCE

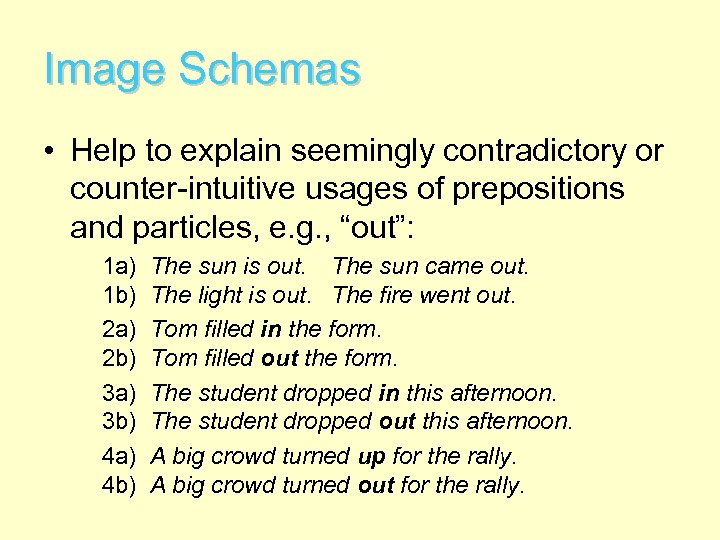

Image Schemas • Help to explain seemingly contradictory or counter-intuitive usages of prepositions and particles, e. g. , “out”: 1 a) 1 b) 2 a) 2 b) 3 a) 3 b) 4 a) 4 b) The sun is out. The sun came out. The light is out. The fire went out. Tom filled in the form. Tom filled out the form. The student dropped in this afternoon. The student dropped out this afternoon. A big crowd turned up for the rally. A big crowd turned out for the rally.

Image Schemas • Help to explain seemingly contradictory or counter-intuitive usages of prepositions and particles, e. g. , “out”: 1 a) 1 b) 2 a) 2 b) 3 a) 3 b) 4 a) 4 b) The sun is out. The sun came out. The light is out. The fire went out. Tom filled in the form. Tom filled out the form. The student dropped in this afternoon. The student dropped out this afternoon. A big crowd turned up for the rally. A big crowd turned out for the rally.

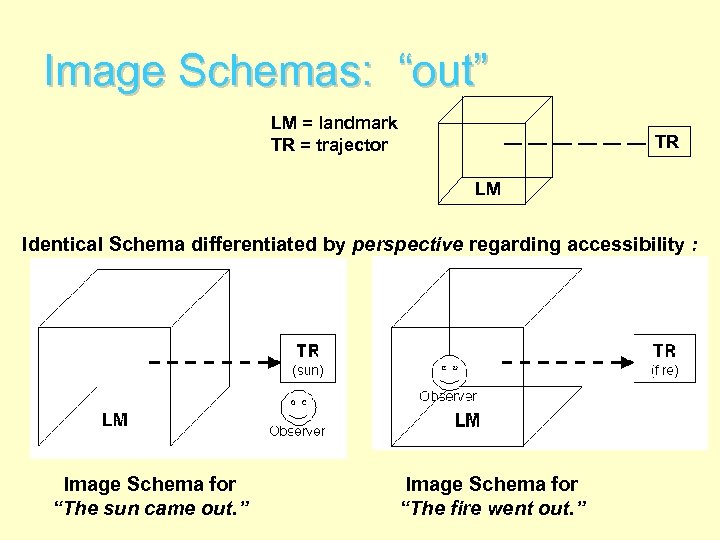

Image Schemas: “out” LM = landmark TR = trajector TR LM Identical Schema differentiated by perspective regarding accessibility : Image Schema for “The sun came out. ” Image Schema for “The fire went out. ”

Image Schemas: “out” LM = landmark TR = trajector TR LM Identical Schema differentiated by perspective regarding accessibility : Image Schema for “The sun came out. ” Image Schema for “The fire went out. ”

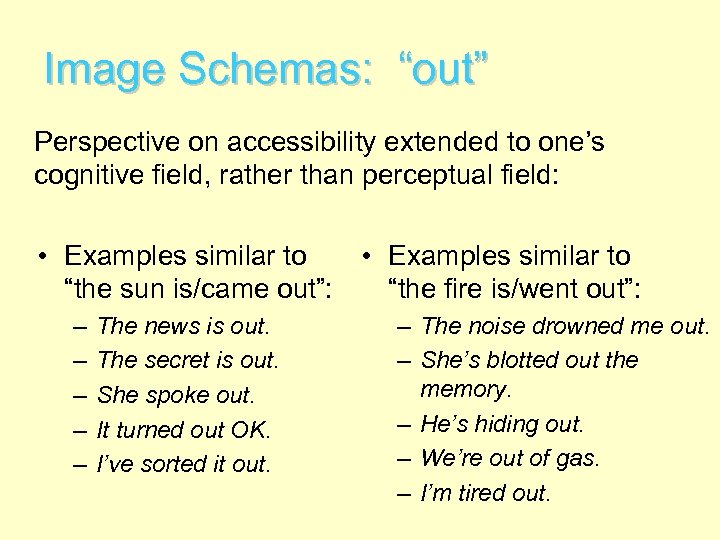

Image Schemas: “out” Perspective on accessibility extended to one’s cognitive field, rather than perceptual field: • Examples similar to “the sun is/came out”: “the fire is/went out”: – – – The news is out. The secret is out. She spoke out. It turned out OK. I’ve sorted it out. – The noise drowned me out. – She’s blotted out the memory. – He’s hiding out. – We’re out of gas. – I’m tired out.

Image Schemas: “out” Perspective on accessibility extended to one’s cognitive field, rather than perceptual field: • Examples similar to “the sun is/came out”: “the fire is/went out”: – – – The news is out. The secret is out. She spoke out. It turned out OK. I’ve sorted it out. – The noise drowned me out. – She’s blotted out the memory. – He’s hiding out. – We’re out of gas. – I’m tired out.

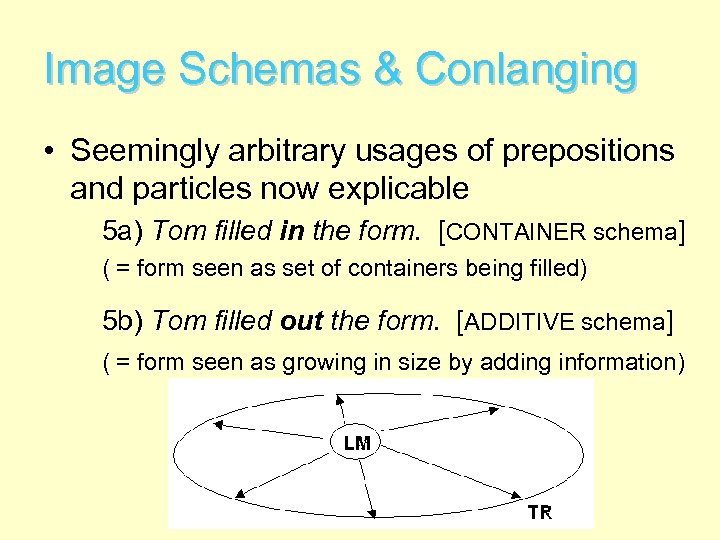

Image Schemas & Conlanging • Seemingly arbitrary usages of prepositions and particles now explicable 5 a) Tom filled in the form. [CONTAINER schema] ( = form seen as set of containers being filled) 5 b) Tom filled out the form. [ADDITIVE schema] ( = form seen as growing in size by adding information)

Image Schemas & Conlanging • Seemingly arbitrary usages of prepositions and particles now explicable 5 a) Tom filled in the form. [CONTAINER schema] ( = form seen as set of containers being filled) 5 b) Tom filled out the form. [ADDITIVE schema] ( = form seen as growing in size by adding information)

Image Schemas & Conlanging • So, should my conlang’s speakers say: – fill ‘in’ a form (CONTAINER + FULL/EMPTY schema), or fill ‘out’ a form (ADDITIVE schema) or some other schema(s) entirely? – Spots ‘on’ or ‘in’ a vase? How about ‘of’ a vase? Wrinkles ‘on’ or ‘in’ her skin? How about ‘at’ her skin? Bubbles ‘on’ or ‘at’ the surface? How about ‘in’? Pictures hanging ‘on’ or ‘from’ the wall? ‘Off’ the wall? • Determine what schema combinations can apply to various spatial and motion contexts, and how they map to your spatial-temporal lexemes

Image Schemas & Conlanging • So, should my conlang’s speakers say: – fill ‘in’ a form (CONTAINER + FULL/EMPTY schema), or fill ‘out’ a form (ADDITIVE schema) or some other schema(s) entirely? – Spots ‘on’ or ‘in’ a vase? How about ‘of’ a vase? Wrinkles ‘on’ or ‘in’ her skin? How about ‘at’ her skin? Bubbles ‘on’ or ‘at’ the surface? How about ‘in’? Pictures hanging ‘on’ or ‘from’ the wall? ‘Off’ the wall? • Determine what schema combinations can apply to various spatial and motion contexts, and how they map to your spatial-temporal lexemes

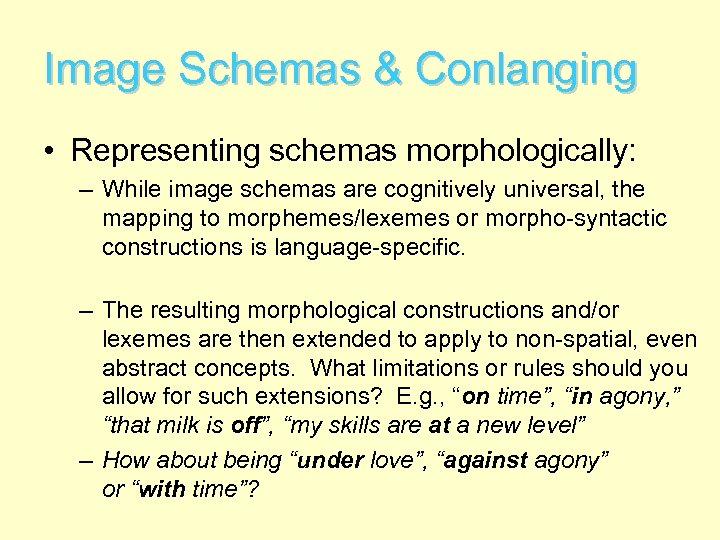

Image Schemas & Conlanging • Representing schemas morphologically: – While image schemas are cognitively universal, the mapping to morphemes/lexemes or morpho-syntactic constructions is language-specific. – The resulting morphological constructions and/or lexemes are then extended to apply to non-spatial, even abstract concepts. What limitations or rules should you allow for such extensions? E. g. , “on time”, “in agony, ” “that milk is off”, “my skills are at a new level” – How about being “under love”, “against agony” or “with time”?

Image Schemas & Conlanging • Representing schemas morphologically: – While image schemas are cognitively universal, the mapping to morphemes/lexemes or morpho-syntactic constructions is language-specific. – The resulting morphological constructions and/or lexemes are then extended to apply to non-spatial, even abstract concepts. What limitations or rules should you allow for such extensions? E. g. , “on time”, “in agony, ” “that milk is off”, “my skills are at a new level” – How about being “under love”, “against agony” or “with time”?

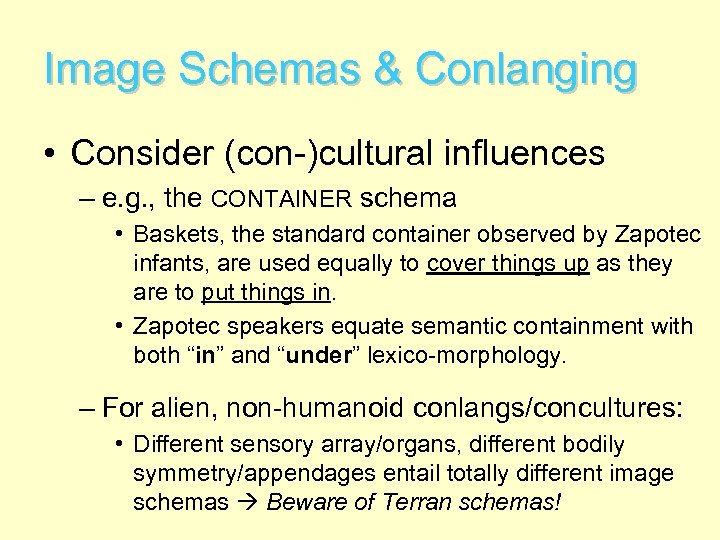

Image Schemas & Conlanging • Consider (con-)cultural influences – e. g. , the CONTAINER schema • Baskets, the standard container observed by Zapotec infants, are used equally to cover things up as they are to put things in. • Zapotec speakers equate semantic containment with both “in” and “under” lexico-morphology. – For alien, non-humanoid conlangs/concultures: • Different sensory array/organs, different bodily symmetry/appendages entail totally different image schemas Beware of Terran schemas!

Image Schemas & Conlanging • Consider (con-)cultural influences – e. g. , the CONTAINER schema • Baskets, the standard container observed by Zapotec infants, are used equally to cover things up as they are to put things in. • Zapotec speakers equate semantic containment with both “in” and “under” lexico-morphology. – For alien, non-humanoid conlangs/concultures: • Different sensory array/organs, different bodily symmetry/appendages entail totally different image schemas Beware of Terran schemas!

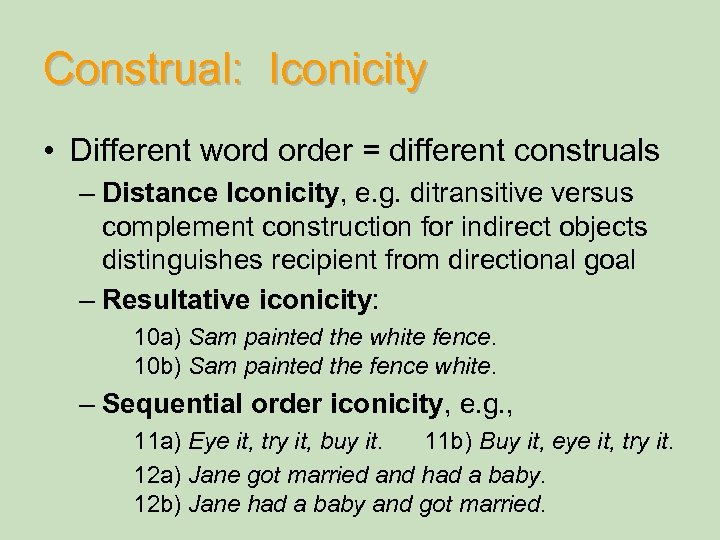

Construal: Iconicity • Different word order = different construals – Distance Iconicity, e. g. ditransitive versus complement construction for indirect objects distinguishes recipient from directional goal – Resultative iconicity: 10 a) Sam painted the white fence. 10 b) Sam painted the fence white. – Sequential order iconicity, e. g. , 11 a) Eye it, try it, buy it. 11 b) Buy it, eye it, try it. 12 a) Jane got married and had a baby. 12 b) Jane had a baby and got married.

Construal: Iconicity • Different word order = different construals – Distance Iconicity, e. g. ditransitive versus complement construction for indirect objects distinguishes recipient from directional goal – Resultative iconicity: 10 a) Sam painted the white fence. 10 b) Sam painted the fence white. – Sequential order iconicity, e. g. , 11 a) Eye it, try it, buy it. 11 b) Buy it, eye it, try it. 12 a) Jane got married and had a baby. 12 b) Jane had a baby and got married.

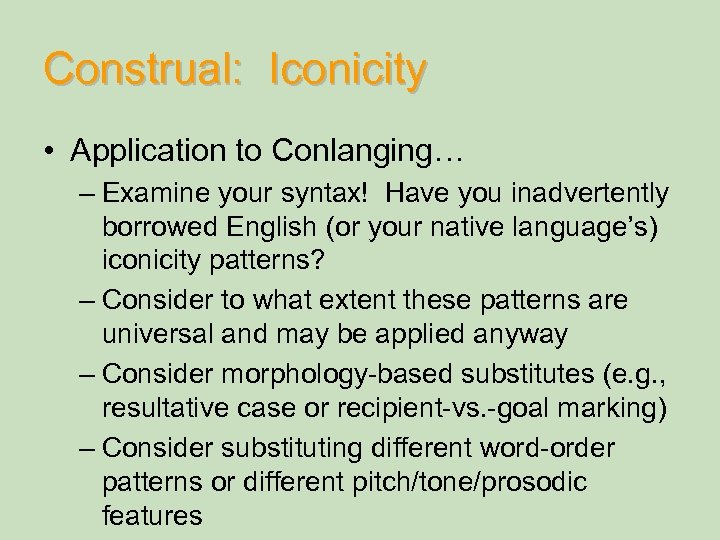

Construal: Iconicity • Application to Conlanging… – Examine your syntax! Have you inadvertently borrowed English (or your native language’s) iconicity patterns? – Consider to what extent these patterns are universal and may be applied anyway – Consider morphology-based substitutes (e. g. , resultative case or recipient-vs. -goal marking) – Consider substituting different word-order patterns or different pitch/tone/prosodic features

Construal: Iconicity • Application to Conlanging… – Examine your syntax! Have you inadvertently borrowed English (or your native language’s) iconicity patterns? – Consider to what extent these patterns are universal and may be applied anyway – Consider morphology-based substitutes (e. g. , resultative case or recipient-vs. -goal marking) – Consider substituting different word-order patterns or different pitch/tone/prosodic features

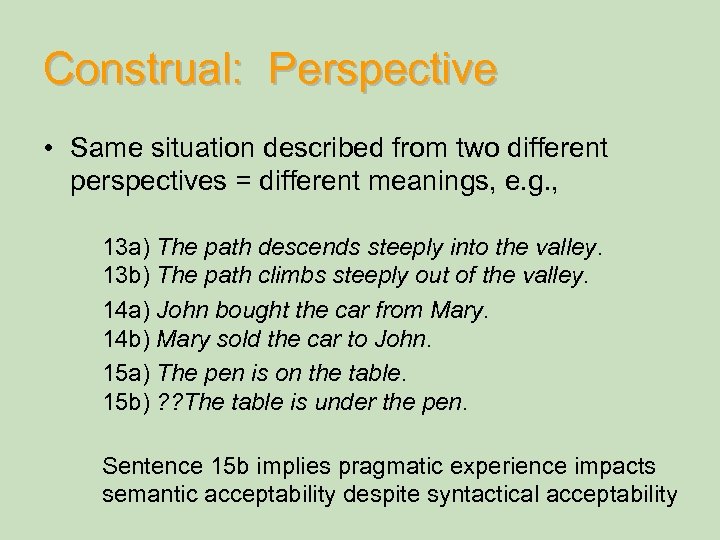

Construal: Perspective • Same situation described from two different perspectives = different meanings, e. g. , 13 a) The path descends steeply into the valley. 13 b) The path climbs steeply out of the valley. 14 a) John bought the car from Mary. 14 b) Mary sold the car to John. 15 a) The pen is on the table. 15 b) ? ? The table is under the pen. Sentence 15 b implies pragmatic experience impacts semantic acceptability despite syntactical acceptability

Construal: Perspective • Same situation described from two different perspectives = different meanings, e. g. , 13 a) The path descends steeply into the valley. 13 b) The path climbs steeply out of the valley. 14 a) John bought the car from Mary. 14 b) Mary sold the car to John. 15 a) The pen is on the table. 15 b) ? ? The table is under the pen. Sentence 15 b implies pragmatic experience impacts semantic acceptability despite syntactical acceptability

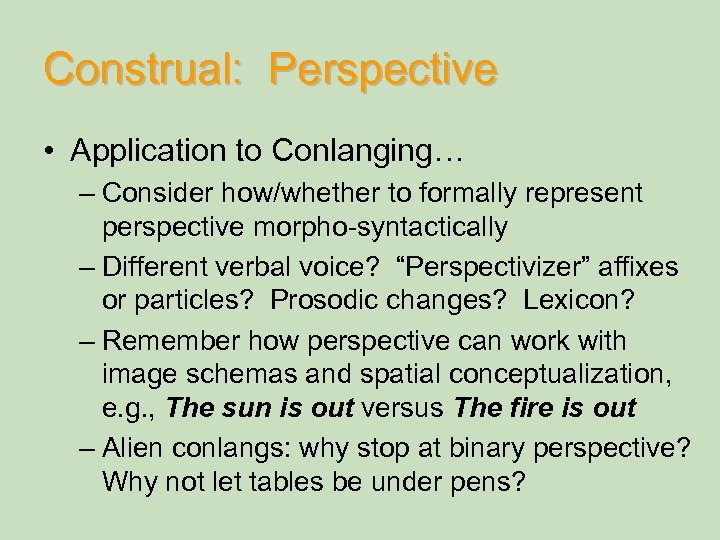

Construal: Perspective • Application to Conlanging… – Consider how/whether to formally represent perspective morpho-syntactically – Different verbal voice? “Perspectivizer” affixes or particles? Prosodic changes? Lexicon? – Remember how perspective can work with image schemas and spatial conceptualization, e. g. , The sun is out versus The fire is out – Alien conlangs: why stop at binary perspective? Why not let tables be under pens?

Construal: Perspective • Application to Conlanging… – Consider how/whether to formally represent perspective morpho-syntactically – Different verbal voice? “Perspectivizer” affixes or particles? Prosodic changes? Lexicon? – Remember how perspective can work with image schemas and spatial conceptualization, e. g. , The sun is out versus The fire is out – Alien conlangs: why stop at binary perspective? Why not let tables be under pens?

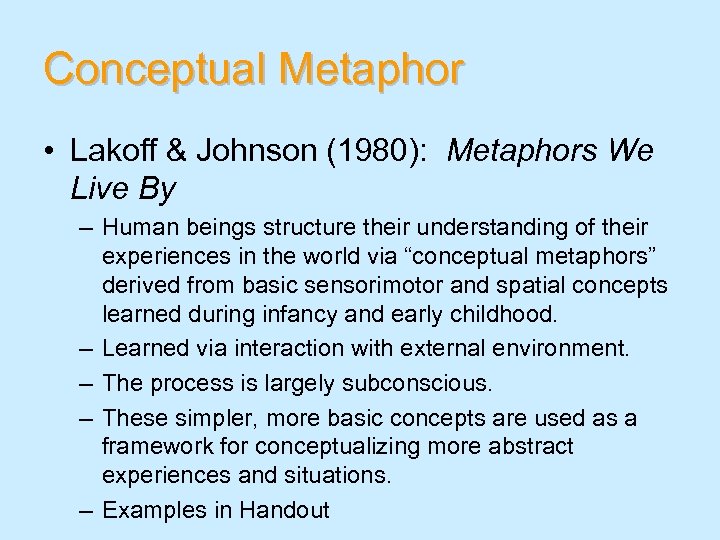

Conceptual Metaphor • Lakoff & Johnson (1980): Metaphors We Live By – Human beings structure their understanding of their experiences in the world via “conceptual metaphors” derived from basic sensorimotor and spatial concepts learned during infancy and early childhood. – Learned via interaction with external environment. – The process is largely subconscious. – These simpler, more basic concepts are used as a framework for conceptualizing more abstract experiences and situations. – Examples in Handout

Conceptual Metaphor • Lakoff & Johnson (1980): Metaphors We Live By – Human beings structure their understanding of their experiences in the world via “conceptual metaphors” derived from basic sensorimotor and spatial concepts learned during infancy and early childhood. – Learned via interaction with external environment. – The process is largely subconscious. – These simpler, more basic concepts are used as a framework for conceptualizing more abstract experiences and situations. – Examples in Handout

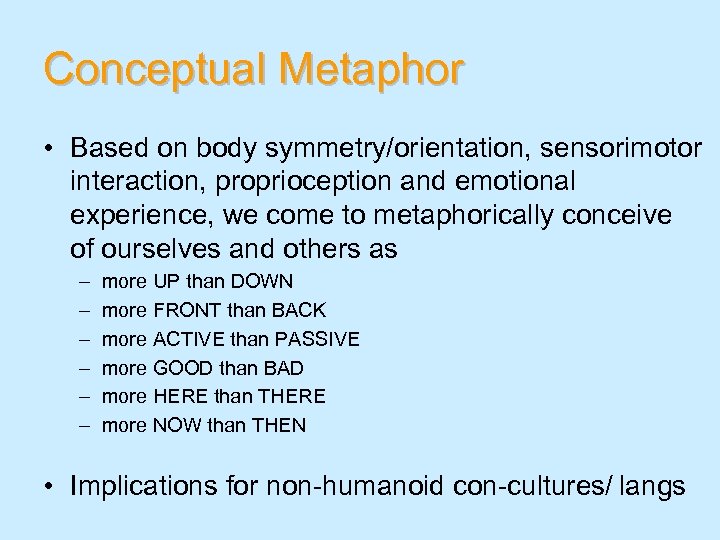

Conceptual Metaphor • Based on body symmetry/orientation, sensorimotor interaction, proprioception and emotional experience, we come to metaphorically conceive of ourselves and others as – – – more UP than DOWN more FRONT than BACK more ACTIVE than PASSIVE more GOOD than BAD more HERE than THERE more NOW than THEN • Implications for non-humanoid con-cultures/ langs

Conceptual Metaphor • Based on body symmetry/orientation, sensorimotor interaction, proprioception and emotional experience, we come to metaphorically conceive of ourselves and others as – – – more UP than DOWN more FRONT than BACK more ACTIVE than PASSIVE more GOOD than BAD more HERE than THERE more NOW than THEN • Implications for non-humanoid con-cultures/ langs

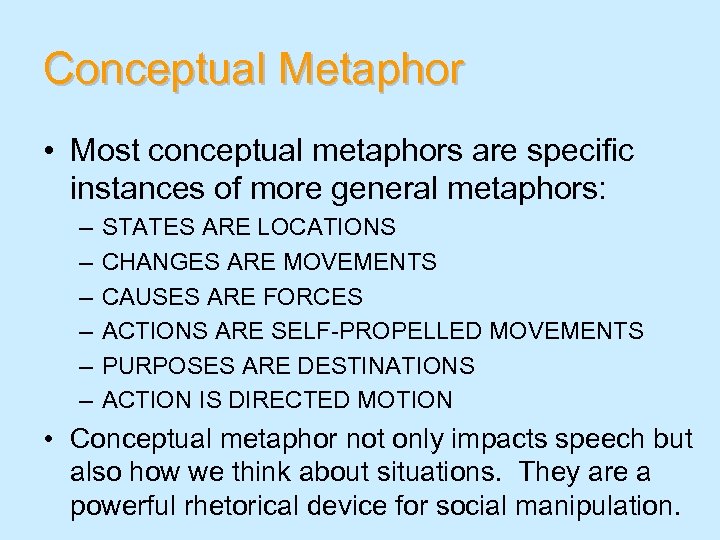

Conceptual Metaphor • Most conceptual metaphors are specific instances of more general metaphors: – – – STATES ARE LOCATIONS CHANGES ARE MOVEMENTS CAUSES ARE FORCES ACTIONS ARE SELF-PROPELLED MOVEMENTS PURPOSES ARE DESTINATIONS ACTION IS DIRECTED MOTION • Conceptual metaphor not only impacts speech but also how we think about situations. They are a powerful rhetorical device for social manipulation.

Conceptual Metaphor • Most conceptual metaphors are specific instances of more general metaphors: – – – STATES ARE LOCATIONS CHANGES ARE MOVEMENTS CAUSES ARE FORCES ACTIONS ARE SELF-PROPELLED MOVEMENTS PURPOSES ARE DESTINATIONS ACTION IS DIRECTED MOTION • Conceptual metaphor not only impacts speech but also how we think about situations. They are a powerful rhetorical device for social manipulation.

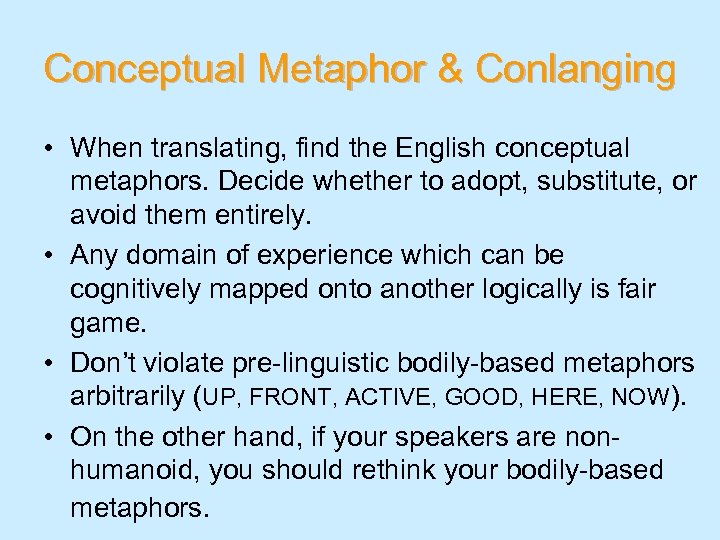

Conceptual Metaphor & Conlanging • When translating, find the English conceptual metaphors. Decide whether to adopt, substitute, or avoid them entirely. • Any domain of experience which can be cognitively mapped onto another logically is fair game. • Don’t violate pre-linguistic bodily-based metaphors arbitrarily (UP, FRONT, ACTIVE, GOOD, HERE, NOW). • On the other hand, if your speakers are nonhumanoid, you should rethink your bodily-based metaphors.

Conceptual Metaphor & Conlanging • When translating, find the English conceptual metaphors. Decide whether to adopt, substitute, or avoid them entirely. • Any domain of experience which can be cognitively mapped onto another logically is fair game. • Don’t violate pre-linguistic bodily-based metaphors arbitrarily (UP, FRONT, ACTIVE, GOOD, HERE, NOW). • On the other hand, if your speakers are nonhumanoid, you should rethink your bodily-based metaphors.

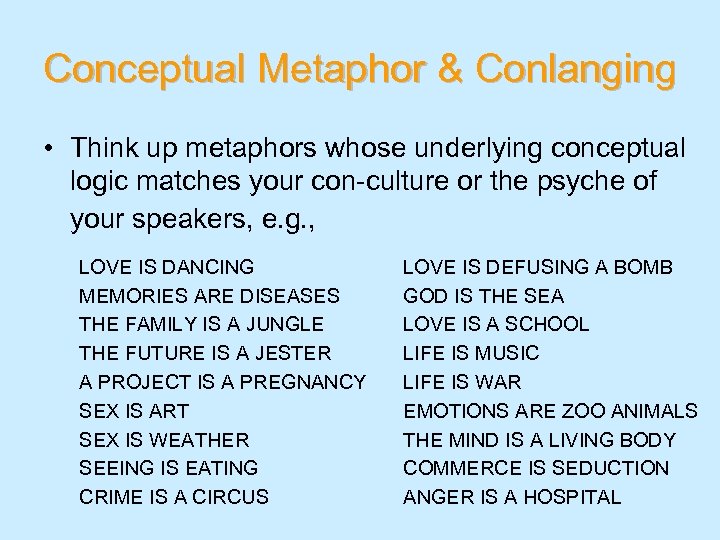

Conceptual Metaphor & Conlanging • Think up metaphors whose underlying conceptual logic matches your con-culture or the psyche of your speakers, e. g. , LOVE IS DANCING MEMORIES ARE DISEASES THE FAMILY IS A JUNGLE THE FUTURE IS A JESTER A PROJECT IS A PREGNANCY SEX IS ART SEX IS WEATHER SEEING IS EATING CRIME IS A CIRCUS LOVE IS DEFUSING A BOMB GOD IS THE SEA LOVE IS A SCHOOL LIFE IS MUSIC LIFE IS WAR EMOTIONS ARE ZOO ANIMALS THE MIND IS A LIVING BODY COMMERCE IS SEDUCTION ANGER IS A HOSPITAL

Conceptual Metaphor & Conlanging • Think up metaphors whose underlying conceptual logic matches your con-culture or the psyche of your speakers, e. g. , LOVE IS DANCING MEMORIES ARE DISEASES THE FAMILY IS A JUNGLE THE FUTURE IS A JESTER A PROJECT IS A PREGNANCY SEX IS ART SEX IS WEATHER SEEING IS EATING CRIME IS A CIRCUS LOVE IS DEFUSING A BOMB GOD IS THE SEA LOVE IS A SCHOOL LIFE IS MUSIC LIFE IS WAR EMOTIONS ARE ZOO ANIMALS THE MIND IS A LIVING BODY COMMERCE IS SEDUCTION ANGER IS A HOSPITAL

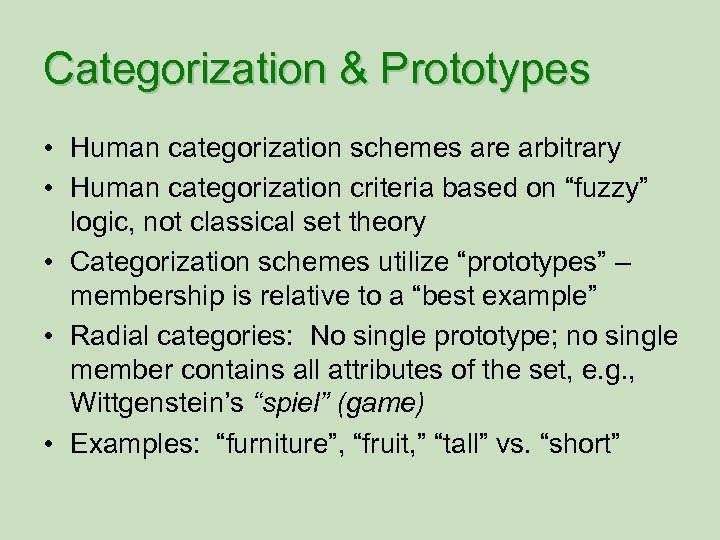

Categorization & Prototypes • Human categorization schemes are arbitrary • Human categorization criteria based on “fuzzy” logic, not classical set theory • Categorization schemes utilize “prototypes” – membership is relative to a “best example” • Radial categories: No single prototype; no single member contains all attributes of the set, e. g. , Wittgenstein’s “spiel” (game) • Examples: “furniture”, “fruit, ” “tall” vs. “short”

Categorization & Prototypes • Human categorization schemes are arbitrary • Human categorization criteria based on “fuzzy” logic, not classical set theory • Categorization schemes utilize “prototypes” – membership is relative to a “best example” • Radial categories: No single prototype; no single member contains all attributes of the set, e. g. , Wittgenstein’s “spiel” (game) • Examples: “furniture”, “fruit, ” “tall” vs. “short”

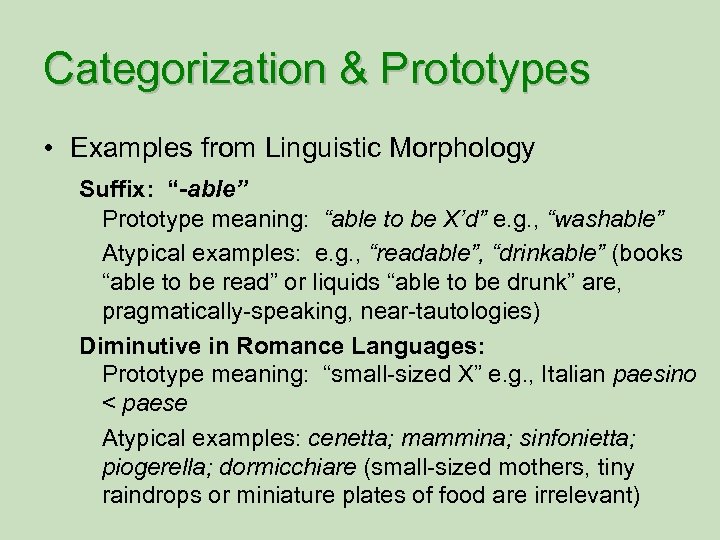

Categorization & Prototypes • Examples from Linguistic Morphology Suffix: “-able” Prototype meaning: “able to be X’d” e. g. , “washable” Atypical examples: e. g. , “readable”, “drinkable” (books “able to be read” or liquids “able to be drunk” are, pragmatically-speaking, near-tautologies) Diminutive in Romance Languages: Prototype meaning: “small-sized X” e. g. , Italian paesino < paese Atypical examples: cenetta; mammina; sinfonietta; piogerella; dormicchiare (small-sized mothers, tiny raindrops or miniature plates of food are irrelevant)

Categorization & Prototypes • Examples from Linguistic Morphology Suffix: “-able” Prototype meaning: “able to be X’d” e. g. , “washable” Atypical examples: e. g. , “readable”, “drinkable” (books “able to be read” or liquids “able to be drunk” are, pragmatically-speaking, near-tautologies) Diminutive in Romance Languages: Prototype meaning: “small-sized X” e. g. , Italian paesino < paese Atypical examples: cenetta; mammina; sinfonietta; piogerella; dormicchiare (small-sized mothers, tiny raindrops or miniature plates of food are irrelevant)

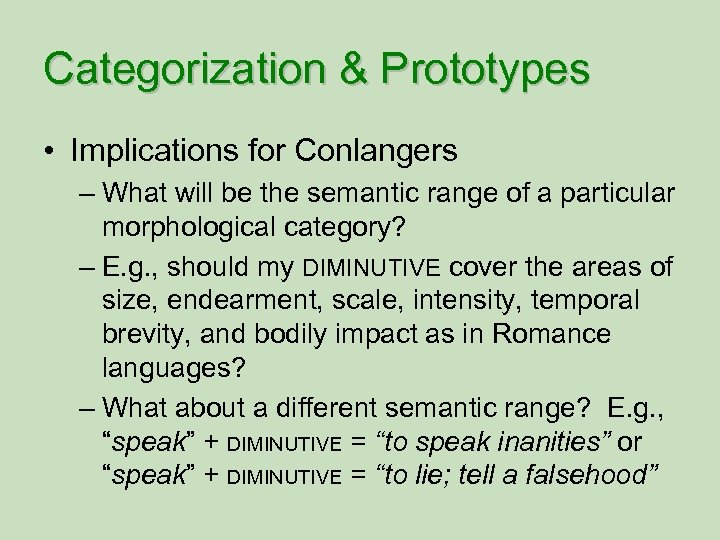

Categorization & Prototypes • Implications for Conlangers – What will be the semantic range of a particular morphological category? – E. g. , should my DIMINUTIVE cover the areas of size, endearment, scale, intensity, temporal brevity, and bodily impact as in Romance languages? – What about a different semantic range? E. g. , “speak” + DIMINUTIVE = “to speak inanities” or “speak” + DIMINUTIVE = “to lie; tell a falsehood”

Categorization & Prototypes • Implications for Conlangers – What will be the semantic range of a particular morphological category? – E. g. , should my DIMINUTIVE cover the areas of size, endearment, scale, intensity, temporal brevity, and bodily impact as in Romance languages? – What about a different semantic range? E. g. , “speak” + DIMINUTIVE = “to speak inanities” or “speak” + DIMINUTIVE = “to lie; tell a falsehood”

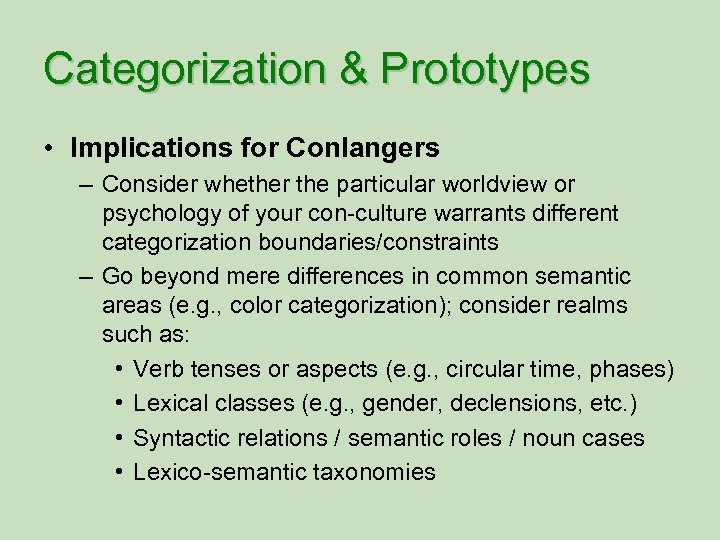

Categorization & Prototypes • Implications for Conlangers – Consider whether the particular worldview or psychology of your con-culture warrants different categorization boundaries/constraints – Go beyond mere differences in common semantic areas (e. g. , color categorization); consider realms such as: • Verb tenses or aspects (e. g. , circular time, phases) • Lexical classes (e. g. , gender, declensions, etc. ) • Syntactic relations / semantic roles / noun cases • Lexico-semantic taxonomies

Categorization & Prototypes • Implications for Conlangers – Consider whether the particular worldview or psychology of your con-culture warrants different categorization boundaries/constraints – Go beyond mere differences in common semantic areas (e. g. , color categorization); consider realms such as: • Verb tenses or aspects (e. g. , circular time, phases) • Lexical classes (e. g. , gender, declensions, etc. ) • Syntactic relations / semantic roles / noun cases • Lexico-semantic taxonomies

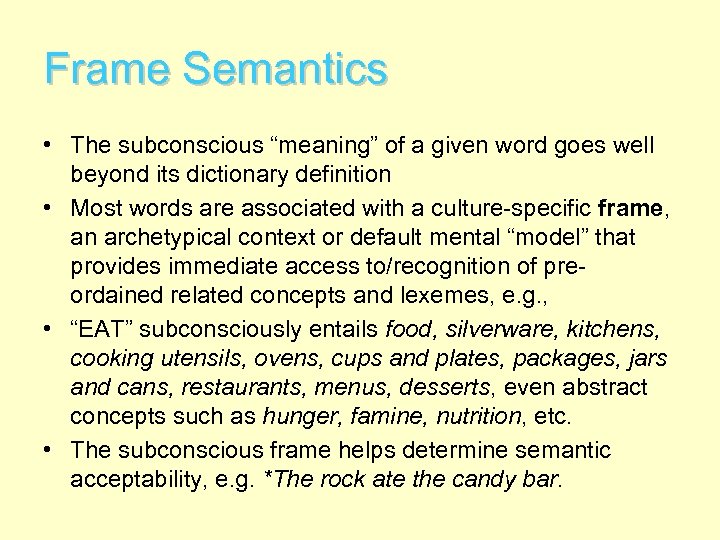

Frame Semantics • The subconscious “meaning” of a given word goes well beyond its dictionary definition • Most words are associated with a culture-specific frame, an archetypical context or default mental “model” that provides immediate access to/recognition of preordained related concepts and lexemes, e. g. , • “EAT” subconsciously entails food, silverware, kitchens, cooking utensils, ovens, cups and plates, packages, jars and cans, restaurants, menus, desserts, even abstract concepts such as hunger, famine, nutrition, etc. • The subconscious frame helps determine semantic acceptability, e. g. *The rock ate the candy bar.

Frame Semantics • The subconscious “meaning” of a given word goes well beyond its dictionary definition • Most words are associated with a culture-specific frame, an archetypical context or default mental “model” that provides immediate access to/recognition of preordained related concepts and lexemes, e. g. , • “EAT” subconsciously entails food, silverware, kitchens, cooking utensils, ovens, cups and plates, packages, jars and cans, restaurants, menus, desserts, even abstract concepts such as hunger, famine, nutrition, etc. • The subconscious frame helps determine semantic acceptability, e. g. *The rock ate the candy bar.

Frame Semantics • Frames demonstrate that meanings of words are not feature-based, e. g. , are the following persons bachelors? = [+MALE] [+ADULT][-MARRIED] – – The Pope Tarzan A man living with his longtime girlfriend A gay man living with his longtime boyfriend • Frames connote an entire network of cultural information – excellent opportunity for integration with your conculture

Frame Semantics • Frames demonstrate that meanings of words are not feature-based, e. g. , are the following persons bachelors? = [+MALE] [+ADULT][-MARRIED] – – The Pope Tarzan A man living with his longtime girlfriend A gay man living with his longtime boyfriend • Frames connote an entire network of cultural information – excellent opportunity for integration with your conculture

Frame Semantics • Frames involve interactional properties not inherent within the word itself, e. g. “fake” + “gun” – Must look like a real gun (you can’t use a dish-towel as a “fake gun”), i. e. , “fake” preserves a perceptual property – Purpose must allow it to be handled like a real gun (e. g. , as threat), i. e. “fake” preserves a motor-activity property – Must serve some purposes of a real gun (e. g. , threat, for display), i. e. “fake” preserves a purposive property – It can’t shoot bullets, i. e. , “fake” negates the primary functional property – It cannot have once been real (a broken gun is not a “fake gun”), i. e. , it negates a historical property

Frame Semantics • Frames involve interactional properties not inherent within the word itself, e. g. “fake” + “gun” – Must look like a real gun (you can’t use a dish-towel as a “fake gun”), i. e. , “fake” preserves a perceptual property – Purpose must allow it to be handled like a real gun (e. g. , as threat), i. e. “fake” preserves a motor-activity property – Must serve some purposes of a real gun (e. g. , threat, for display), i. e. “fake” preserves a purposive property – It can’t shoot bullets, i. e. , “fake” negates the primary functional property – It cannot have once been real (a broken gun is not a “fake gun”), i. e. , it negates a historical property

Frame Semantics • These interactional properties “emerge” from the juxtaposition of “fake” + “gun” • These five properties (perceptual, motor-activity, purposive, functional, and historical) operate as an experiential gestalt • Another example: “KILLING” entails… – CAUSE OF DEATH, INSTRUMENT, METHOD, PERPETRATOR, VICTIM, DEGREE, MANNER, PLACE, PURPOSE, REASON, RESULT • Frames for English listed on Frame. Net website http: //framenet. icsi. berkeley. edu/

Frame Semantics • These interactional properties “emerge” from the juxtaposition of “fake” + “gun” • These five properties (perceptual, motor-activity, purposive, functional, and historical) operate as an experiential gestalt • Another example: “KILLING” entails… – CAUSE OF DEATH, INSTRUMENT, METHOD, PERPETRATOR, VICTIM, DEGREE, MANNER, PLACE, PURPOSE, REASON, RESULT • Frames for English listed on Frame. Net website http: //framenet. icsi. berkeley. edu/

Frame Semantics & Conlanging • Determine scope of each word’s frame – Should it parallel English? – Should some elements be missing? (e. g. , historical property of “gun”) – Should I add some elements missing from English? e. g. , adding BODY PART to the “KILLING” frame to allow sentences translatable as “He stomached him to death” or “I throat-killed him. ” • Common frames lend themselves to conlangspecific creativity, e. g. , BUSINESS/COMMERCE, ROMANTIC RELATIONSHIPS, FOOD/EATING, FAMILY, EDUCATION, POLITICS, TRANSPORTATION

Frame Semantics & Conlanging • Determine scope of each word’s frame – Should it parallel English? – Should some elements be missing? (e. g. , historical property of “gun”) – Should I add some elements missing from English? e. g. , adding BODY PART to the “KILLING” frame to allow sentences translatable as “He stomached him to death” or “I throat-killed him. ” • Common frames lend themselves to conlangspecific creativity, e. g. , BUSINESS/COMMERCE, ROMANTIC RELATIONSHIPS, FOOD/EATING, FAMILY, EDUCATION, POLITICS, TRANSPORTATION

Questions?

Questions?