f932a305a5031f1a5933debed9b28f83.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 106

Android Architecture

Android Architecture

Android Operating System

Android Operating System

OS Components • Linux Kernel Android relies on Linux version 2. 6 for core system services such as security, memory management, process management, network stack, and driver model. The kernel also acts as an abstraction layer between the hardware and the rest of the software stack.

OS Components • Linux Kernel Android relies on Linux version 2. 6 for core system services such as security, memory management, process management, network stack, and driver model. The kernel also acts as an abstraction layer between the hardware and the rest of the software stack.

OS Components Android Runtime • Android includes a set of core libraries that provides most of the functionality available in the core libraries of the Java programming language. • Every Android application runs in its own process, with its own instance of the Dalvik virtual machine. • Dalvik has been written so that a device can run multiple VMs efficiently.

OS Components Android Runtime • Android includes a set of core libraries that provides most of the functionality available in the core libraries of the Java programming language. • Every Android application runs in its own process, with its own instance of the Dalvik virtual machine. • Dalvik has been written so that a device can run multiple VMs efficiently.

OS Components Android Runtime • The Dalvik VM executes files in the Dalvik Executable (. dex) format which is optimized for minimal memory footprint. • The VM is register-based, and runs classes compiled by a Java language compiler that have been transformed into the. dex format by the included "dx" tool. • The Dalvik VM relies on the Linux kernel for underlying functionality such as threading and low-level memory management.

OS Components Android Runtime • The Dalvik VM executes files in the Dalvik Executable (. dex) format which is optimized for minimal memory footprint. • The VM is register-based, and runs classes compiled by a Java language compiler that have been transformed into the. dex format by the included "dx" tool. • The Dalvik VM relies on the Linux kernel for underlying functionality such as threading and low-level memory management.

OS Components Libraries • Android includes a set of C/C++ libraries used by various components of the Android system. These capabilities are exposed to developers through the Android application framework. Some of the core libraries are listed below: • System C library - a BSD-derived implementation of the standard C system library (libc), tuned for embedded Linux-based devices • Media Libraries - based on Packet. Video's Open. CORE; the libraries support playback and recording of many popular audio and video formats, as well as static image files, including MPEG 4, H. 264, MP 3, AAC, AMR, JPG, and PNG • Surface Manager - manages access to the display subsystem and seamlessly composites 2 D and 3 D graphic layers from multiple applications

OS Components Libraries • Android includes a set of C/C++ libraries used by various components of the Android system. These capabilities are exposed to developers through the Android application framework. Some of the core libraries are listed below: • System C library - a BSD-derived implementation of the standard C system library (libc), tuned for embedded Linux-based devices • Media Libraries - based on Packet. Video's Open. CORE; the libraries support playback and recording of many popular audio and video formats, as well as static image files, including MPEG 4, H. 264, MP 3, AAC, AMR, JPG, and PNG • Surface Manager - manages access to the display subsystem and seamlessly composites 2 D and 3 D graphic layers from multiple applications

OS Components Libraries • Lib. Web. Core - a modern web browser engine which powers both the Android browser and an embeddable web view • SGL - the underlying 2 D graphics engine • 3 D libraries - an implementation based on Open. GL ES 1. 0 APIs; the libraries use either hardware 3 D acceleration (where available) or the included, highly optimized 3 D software rasterizer • Free. Type - bitmap and vector font rendering • SQLite - a powerful and lightweight relational database engine available to all applications

OS Components Libraries • Lib. Web. Core - a modern web browser engine which powers both the Android browser and an embeddable web view • SGL - the underlying 2 D graphics engine • 3 D libraries - an implementation based on Open. GL ES 1. 0 APIs; the libraries use either hardware 3 D acceleration (where available) or the included, highly optimized 3 D software rasterizer • Free. Type - bitmap and vector font rendering • SQLite - a powerful and lightweight relational database engine available to all applications

OS Components Application Framework • Developers are free to take advantage of the device hardware, access location information, run background services, set alarms, add notifications to the status bar, and much, much more. • Developers have full access to the same framework APIs used by the core applications. The application architecture is designed to simplify the reuse of components; any application can publish its capabilities and any other application may then make use of those capabilities (subject to security constraints enforced by the framework). This same mechanism allows components to be replaced by the user.

OS Components Application Framework • Developers are free to take advantage of the device hardware, access location information, run background services, set alarms, add notifications to the status bar, and much, much more. • Developers have full access to the same framework APIs used by the core applications. The application architecture is designed to simplify the reuse of components; any application can publish its capabilities and any other application may then make use of those capabilities (subject to security constraints enforced by the framework). This same mechanism allows components to be replaced by the user.

OS Components Application Framework • Underlying all applications is a set of services and systems, including: • A rich and extensible set of Views that can be used to build an application, including lists, grids, text boxes, buttons, and even an embeddable web browser • Content Providers that enable applications to access data from other applications (such as Contacts), or to share their own data • A Resource Manager, providing access to non-code resources such as localized strings, graphics, and layout files • A Notification Manager that enables all applications to display custom alerts in the status bar • An Activity Manager that manages the lifecycle of applications and provides a common navigation backstack

OS Components Application Framework • Underlying all applications is a set of services and systems, including: • A rich and extensible set of Views that can be used to build an application, including lists, grids, text boxes, buttons, and even an embeddable web browser • Content Providers that enable applications to access data from other applications (such as Contacts), or to share their own data • A Resource Manager, providing access to non-code resources such as localized strings, graphics, and layout files • A Notification Manager that enables all applications to display custom alerts in the status bar • An Activity Manager that manages the lifecycle of applications and provides a common navigation backstack

Application Fundamentals • Android applications are written in the Java programming language. • The compiled Java code — along with any data and resource files required by the application — is bundled by the aapt tool into an Android package, an archive file marked by an. apk suffix. • This file is the vehicle for distributing the application and installing it on mobile devices; it's the file users download to their devices. All the code in a single. apk file is considered to be one application.

Application Fundamentals • Android applications are written in the Java programming language. • The compiled Java code — along with any data and resource files required by the application — is bundled by the aapt tool into an Android package, an archive file marked by an. apk suffix. • This file is the vehicle for distributing the application and installing it on mobile devices; it's the file users download to their devices. All the code in a single. apk file is considered to be one application.

Application Fundamentals • By default, every application runs in its own Linux process. Android starts the process when any of the application's code needs to be executed, and shuts down the process when it's no longer needed and system resources are required by other applications. • Each process has its own virtual machine (VM), so application code runs in isolation from the code of all other applications.

Application Fundamentals • By default, every application runs in its own Linux process. Android starts the process when any of the application's code needs to be executed, and shuts down the process when it's no longer needed and system resources are required by other applications. • Each process has its own virtual machine (VM), so application code runs in isolation from the code of all other applications.

Application Fundamentals • By default, each application is assigned a unique Linux user ID. Permissions are set so that the application's files are visible only to that user and only to the application itself — although there are ways to export them to other applications as well. • It's possible to arrange for two applications to share the same user ID, in which case they will be able to see each other's files. To conserve system resources, applications with the same ID can also arrange to run in the same Linux process, sharing the same VM.

Application Fundamentals • By default, each application is assigned a unique Linux user ID. Permissions are set so that the application's files are visible only to that user and only to the application itself — although there are ways to export them to other applications as well. • It's possible to arrange for two applications to share the same user ID, in which case they will be able to see each other's files. To conserve system resources, applications with the same ID can also arrange to run in the same Linux process, sharing the same VM.

Application Components • An Android application can make use of elements of other applications. If your application needs to display a scrolling list of images and another application has developed a suitable scroller and made it available to others, you can call upon that scroller to do the work. • Your application simply starts up that piece of the other application when the need arises.

Application Components • An Android application can make use of elements of other applications. If your application needs to display a scrolling list of images and another application has developed a suitable scroller and made it available to others, you can call upon that scroller to do the work. • Your application simply starts up that piece of the other application when the need arises.

Application Components • The system must start an application process when any part of it is needed, and instantiate the Java objects for that part. Android applications don't have a single entry point (no main() function). • Android applications have essential components that the system can instantiate and run as needed.

Application Components • The system must start an application process when any part of it is needed, and instantiate the Java objects for that part. Android applications don't have a single entry point (no main() function). • Android applications have essential components that the system can instantiate and run as needed.

Four Component Types Activities • • • Present a visual user interface for one focused endeavor the user can undertake. Example - Present a list of menu items users can choose from or it might display photographs along with their captions. Example - A text messaging application might have one activity that shows a list of contacts to send messages to, a second activity to write the message to the chosen contact, and other activities to review old messages or change settings.

Four Component Types Activities • • • Present a visual user interface for one focused endeavor the user can undertake. Example - Present a list of menu items users can choose from or it might display photographs along with their captions. Example - A text messaging application might have one activity that shows a list of contacts to send messages to, a second activity to write the message to the chosen contact, and other activities to review old messages or change settings.

Activities • • Each activity is independent of the others. Each one is implemented as a subclass of the Activity base class. Typically, one of the activities is marked as the first one that should be presented to the user when the application is launched. Moving from one activity to another is accomplished by having the current activity start the next one.

Activities • • Each activity is independent of the others. Each one is implemented as a subclass of the Activity base class. Typically, one of the activities is marked as the first one that should be presented to the user when the application is launched. Moving from one activity to another is accomplished by having the current activity start the next one.

Four Component Types Activities • The visual content of the window is provided by a hierarchy of views — objects derived from the base View class. • Each view controls a particular rectangular space within the window. Parent views contain and organize the layout of their children. • Leaf views (those at the bottom of the hierarchy) draw in the rectangles they control and respond to user actions directed at that space.

Four Component Types Activities • The visual content of the window is provided by a hierarchy of views — objects derived from the base View class. • Each view controls a particular rectangular space within the window. Parent views contain and organize the layout of their children. • Leaf views (those at the bottom of the hierarchy) draw in the rectangles they control and respond to user actions directed at that space.

Activity Views • Views are where the activity's interaction with the user takes place. A view might display a small image and respond when the user taps that image. • Android has a number of ready-made views that you can use — including buttons, text fields, scroll bars, menu items, check boxes, and more. • A view hierarchy is placed within an activity's window by the Activity. set. Content. View() method. • The content view is the View object at the root of the hierarchy.

Activity Views • Views are where the activity's interaction with the user takes place. A view might display a small image and respond when the user taps that image. • Android has a number of ready-made views that you can use — including buttons, text fields, scroll bars, menu items, check boxes, and more. • A view hierarchy is placed within an activity's window by the Activity. set. Content. View() method. • The content view is the View object at the root of the hierarchy.

Four Component Types Services • A service doesn't have a visual user interface, but rather runs in the background for an indefinite period of time. • Each service extends the Service base class. • A good example of a service is a media player playing songs. One or more player activities would allow the user to choose songs and start playing them. The music playback itself would not be handled by an activity (users will expect the music to keep playing ). The media player activity could start a service to run in the background.

Four Component Types Services • A service doesn't have a visual user interface, but rather runs in the background for an indefinite period of time. • Each service extends the Service base class. • A good example of a service is a media player playing songs. One or more player activities would allow the user to choose songs and start playing them. The music playback itself would not be handled by an activity (users will expect the music to keep playing ). The media player activity could start a service to run in the background.

Services • It's possible to connect to (bind to) an ongoing service (and start the service if it's not already running). While connected, you can communicate with the service through an interface that the service exposes. For the music service, this interface might allow users to pause, rewind, stop, and restart the playback. • Like activities and the other components, services run in the main thread of the application process. So that they won't block other components or the user interface, they often spawn another thread for time-consuming tasks (like music playback).

Services • It's possible to connect to (bind to) an ongoing service (and start the service if it's not already running). While connected, you can communicate with the service through an interface that the service exposes. For the music service, this interface might allow users to pause, rewind, stop, and restart the playback. • Like activities and the other components, services run in the main thread of the application process. So that they won't block other components or the user interface, they often spawn another thread for time-consuming tasks (like music playback).

Four Component Types Broadcast receivers • A broadcast receiver is a component that does nothing but receive and react to broadcast announcements. • Many broadcasts originate in system code — for example, announcements that the timezone has changed, that the battery is low, that a picture has been taken, or that the user changed a language preference. • Applications can also initiate broadcasts — for example, to let other applications know that some data has been downloaded to the device and is available for them to use.

Four Component Types Broadcast receivers • A broadcast receiver is a component that does nothing but receive and react to broadcast announcements. • Many broadcasts originate in system code — for example, announcements that the timezone has changed, that the battery is low, that a picture has been taken, or that the user changed a language preference. • Applications can also initiate broadcasts — for example, to let other applications know that some data has been downloaded to the device and is available for them to use.

Broadcast Receiver • An application can have any number of broadcast receivers to respond to any announcements it considers important. All receivers extend the Broadcast. Receiver base class. • Broadcast receivers do not display a user interface. However, they may start an activity in response to the information they receive, or they may use the Notification. Manager to alert the user. • Notifications can get the user's attention in various ways — flashing the backlight, vibrating the device, playing a sound, and so on. They typically place a persistent icon in the status bar, which users can open to get the message.

Broadcast Receiver • An application can have any number of broadcast receivers to respond to any announcements it considers important. All receivers extend the Broadcast. Receiver base class. • Broadcast receivers do not display a user interface. However, they may start an activity in response to the information they receive, or they may use the Notification. Manager to alert the user. • Notifications can get the user's attention in various ways — flashing the backlight, vibrating the device, playing a sound, and so on. They typically place a persistent icon in the status bar, which users can open to get the message.

Four Component Types Content providers • A content provider makes a specific set of the application's data available to other applications. The data can be stored in the file system, in an SQLite database, or in any other manner that makes sense. • The content provider extends the Content. Provider base class to implement a standard set of methods that enable other applications to retrieve and store data of the type it controls. • Applications do not call these methods directly. Rather they use a Content. Resolver object and call its methods instead. A Content. Resolver can talk to any content provider; it cooperates with the provider to manage any interprocess communication that's involved.

Four Component Types Content providers • A content provider makes a specific set of the application's data available to other applications. The data can be stored in the file system, in an SQLite database, or in any other manner that makes sense. • The content provider extends the Content. Provider base class to implement a standard set of methods that enable other applications to retrieve and store data of the type it controls. • Applications do not call these methods directly. Rather they use a Content. Resolver object and call its methods instead. A Content. Resolver can talk to any content provider; it cooperates with the provider to manage any interprocess communication that's involved.

Activating components: intents • Content providers are activated when they're targeted by a request from a Content. Resolver. • Activities, services, and broadcast receivers — are activated by asynchronous messages called intents. • An intent is an Intent object that holds the content of the message.

Activating components: intents • Content providers are activated when they're targeted by a request from a Content. Resolver. • Activities, services, and broadcast receivers — are activated by asynchronous messages called intents. • An intent is an Intent object that holds the content of the message.

Intents • For activities and services, the Intent names the action being requested and specifies the URI of the data to act on. For example, it might convey a request for an activity to present an image to the user or let the user edit some text. • For broadcast receivers, the Intent object names the action being announced. For example, it might announce to interested parties that the camera button has been pressed.

Intents • For activities and services, the Intent names the action being requested and specifies the URI of the data to act on. For example, it might convey a request for an activity to present an image to the user or let the user edit some text. • For broadcast receivers, the Intent object names the action being announced. For example, it might announce to interested parties that the camera button has been pressed.

Methods for Activating an Activity • An activity is launched (or given something new to do) by passing an Intent object to Context. start. Activity() or Activity. start. Activity. For. Result(). • The responding activity can look at the initial intent that caused it to be launched by calling its get. Intent() method. • Android calls the activity's on. New. Intent() method to pass it any subsequent intents.

Methods for Activating an Activity • An activity is launched (or given something new to do) by passing an Intent object to Context. start. Activity() or Activity. start. Activity. For. Result(). • The responding activity can look at the initial intent that caused it to be launched by calling its get. Intent() method. • Android calls the activity's on. New. Intent() method to pass it any subsequent intents.

Methods for Activating an Activity • One activity often starts the next one. If it expects a result back from the activity it's starting, it calls start. Activity. For. Result() instead of start. Activity(). For example, if it starts an activity that lets the user pick a photo, it might expect to be returned the chosen photo. The result is returned in an Intent object that's passed to the calling activity's on. Activity. Result() method.

Methods for Activating an Activity • One activity often starts the next one. If it expects a result back from the activity it's starting, it calls start. Activity. For. Result() instead of start. Activity(). For example, if it starts an activity that lets the user pick a photo, it might expect to be returned the chosen photo. The result is returned in an Intent object that's passed to the calling activity's on. Activity. Result() method.

Methods for Activating a Service • A service is started (or new instructions are given to an ongoing service) by passing an Intent object to Context. start. Service(). • Android calls the service's on. Start() method and passes it the Intent object. • Similarly, an intent can be passed to Context. bind. Service() to establish an ongoing connection between the calling component and a target service. The service receives the Intent object in an on. Bind() call. (If the service is not already running, bind. Service() can optionally start it. )

Methods for Activating a Service • A service is started (or new instructions are given to an ongoing service) by passing an Intent object to Context. start. Service(). • Android calls the service's on. Start() method and passes it the Intent object. • Similarly, an intent can be passed to Context. bind. Service() to establish an ongoing connection between the calling component and a target service. The service receives the Intent object in an on. Bind() call. (If the service is not already running, bind. Service() can optionally start it. )

Methods for Activating a Service • For example, an activity might establish a connection with the music playback service mentioned earlier so that it can provide the user with the means (a user interface) for controlling the playback. The activity would call bind. Service() to set up that connection, and then call methods defined by the service to affect the playback. • An application can initiate a broadcast by passing an Intent object to methods like Context. send. Broadcast(), Context. send. Ordered. Broadcast(), and Context. send. Sticky. Broadcast() in any of their variations. • Android delivers the intent to all interested broadcast receivers by calling their on. Receive() methods.

Methods for Activating a Service • For example, an activity might establish a connection with the music playback service mentioned earlier so that it can provide the user with the means (a user interface) for controlling the playback. The activity would call bind. Service() to set up that connection, and then call methods defined by the service to affect the playback. • An application can initiate a broadcast by passing an Intent object to methods like Context. send. Broadcast(), Context. send. Ordered. Broadcast(), and Context. send. Sticky. Broadcast() in any of their variations. • Android delivers the intent to all interested broadcast receivers by calling their on. Receive() methods.

Shutting down components • Content providers and broadcast receivers don’t need to be explicitly shut down. • A content provider is active only while it's responding to a request from a Content. Resolver. • A broadcast receiver is active only while it's responding to a broadcast message. • Activities, on the other hand, provide the user interface. They're in a long-running conversation with the user and may remain active, even when idle, as long as the conversation continues. • Services may also remain running for a long time. Android has methods to shut down activities and services in an orderly way.

Shutting down components • Content providers and broadcast receivers don’t need to be explicitly shut down. • A content provider is active only while it's responding to a request from a Content. Resolver. • A broadcast receiver is active only while it's responding to a broadcast message. • Activities, on the other hand, provide the user interface. They're in a long-running conversation with the user and may remain active, even when idle, as long as the conversation continues. • Services may also remain running for a long time. Android has methods to shut down activities and services in an orderly way.

Shutting down components • An activity can be shut down by calling its finish() method. One activity can shut down another activity (one it started with start. Activity. For. Result()) by calling finish. Activity(). • A service can be stopped by calling its stop. Self() method, or by calling Context. stop. Service(). • Components might also be shut down by the system when they are no longer being used or when Android must reclaim memory for more active components.

Shutting down components • An activity can be shut down by calling its finish() method. One activity can shut down another activity (one it started with start. Activity. For. Result()) by calling finish. Activity(). • A service can be stopped by calling its stop. Self() method, or by calling Context. stop. Service(). • Components might also be shut down by the system when they are no longer being used or when Android must reclaim memory for more active components.

The Manifest File • Before Android can start an application component, it must learn that the component exists. Therefore, applications declare their components in a manifest file that's bundled into the Android package, the. apk file that also holds the application's code, files, and resources. • The manifest is a structured XML file and is always named Android. Manifest. xml for all applications. • It does a number of things in addition to declaring the application's components, such as naming any libraries the application needs to be linked against (besides the default Android library) and identifying any permissions the application expects to be granted.

The Manifest File • Before Android can start an application component, it must learn that the component exists. Therefore, applications declare their components in a manifest file that's bundled into the Android package, the. apk file that also holds the application's code, files, and resources. • The manifest is a structured XML file and is always named Android. Manifest. xml for all applications. • It does a number of things in addition to declaring the application's components, such as naming any libraries the application needs to be linked against (besides the default Android library) and identifying any permissions the application expects to be granted.

Intent Filters • An Intent object can explicitly name a target component. If it does, Android finds that component (based on the declarations in the manifest file) and activates it. • If a target is not explicitly named, Android must locate the best component to respond to the intent. • Android does so by comparing the Intent object to the intent filters of potential targets. • A component's intent filters inform Android of the kinds of intents the component is able to handle. Like other essential information about the component, they're declared in the manifest file.

Intent Filters • An Intent object can explicitly name a target component. If it does, Android finds that component (based on the declarations in the manifest file) and activates it. • If a target is not explicitly named, Android must locate the best component to respond to the intent. • Android does so by comparing the Intent object to the intent filters of potential targets. • A component's intent filters inform Android of the kinds of intents the component is able to handle. Like other essential information about the component, they're declared in the manifest file.

" src="https://present5.com/presentation/f932a305a5031f1a5933debed9b28f83/image-37.jpg" alt="Intent Filters in a Manifest • • • " />

Intent Filters in a Manifest • • •

" src="https://present5.com/presentation/f932a305a5031f1a5933debed9b28f83/image-38.jpg" alt="Intent Filters in a Manifest • • • " />

Intent Filters in a Manifest • • •

Activities and Tasks • One activity can start another, including one defined in a different application. • Your activity can build an Intent object with the required information and pass it to start. Activity() (say a map viewer) in a different application. The map viewer will display the map. When the user hits the BACK key, your activity will reappear on screen. • Users are unaware that the activities are in different applications. • Android maintains this user experience by keeping both activities in the same task.

Activities and Tasks • One activity can start another, including one defined in a different application. • Your activity can build an Intent object with the required information and pass it to start. Activity() (say a map viewer) in a different application. The map viewer will display the map. When the user hits the BACK key, your activity will reappear on screen. • Users are unaware that the activities are in different applications. • Android maintains this user experience by keeping both activities in the same task.

Activities and Tasks • A task is a group of related activities, arranged in a stack. The root activity in the stack is the one that began the task — typically, it's an activity the user selected in the application launcher. • The activity at the top of the stack is one that's currently running — the one that is the focus for user actions. When one activity starts another, the new activity is pushed on the stack; it becomes the running activity. The previous activity remains in the stack. When the user presses the BACK key, the current activity is popped from the stack, and the previous one resumes as the running activity.

Activities and Tasks • A task is a group of related activities, arranged in a stack. The root activity in the stack is the one that began the task — typically, it's an activity the user selected in the application launcher. • The activity at the top of the stack is one that's currently running — the one that is the focus for user actions. When one activity starts another, the new activity is pushed on the stack; it becomes the running activity. The previous activity remains in the stack. When the user presses the BACK key, the current activity is popped from the stack, and the previous one resumes as the running activity.

Activities and Tasks • The stack contains objects, so if a task has more than one instance of the same Activity subclass open — multiple map viewers, for example — the stack has a separate entry for each instance. Activities in the stack are never rearranged, only pushed and popped. • A task is a stack of activities, not a class or an element in the manifest file. So there's no way to set values for a task independently of its activities. • Values for the task as a whole are set in the root activity.

Activities and Tasks • The stack contains objects, so if a task has more than one instance of the same Activity subclass open — multiple map viewers, for example — the stack has a separate entry for each instance. Activities in the stack are never rearranged, only pushed and popped. • A task is a stack of activities, not a class or an element in the manifest file. So there's no way to set values for a task independently of its activities. • Values for the task as a whole are set in the root activity.

Activities and Tasks • • All the activities in a task move together as a unit. The entire task (the entire activity stack) can be brought to the foreground or sent to the background. Senario: – The current task has four activities in its stack — three under the current activity. – The user presses the HOME key, goes to the application launcher, and selects a new application (actually, a new task). – The current task goes into the background and the root activity for the new task is displayed. Then, after a short period, the user goes back to the home screen and again selects the previous application (the previous task). – That task, with all four activities in the stack, comes forward. When the user presses the BACK key, the screen does not display the activity the user just left (the root activity of the previous task). Rather, the activity on the top of the stack is removed and the previous activity in the same task is displayed. • The behavior just described is the default behavior for activities and tasks. But there are ways to modify almost all aspects of it. The association of activities with tasks, and the behavior of an activity within a task, is controlled by the interaction between flags set in the Intent object that started the activity and attributes set in the activity's

Activities and Tasks • • All the activities in a task move together as a unit. The entire task (the entire activity stack) can be brought to the foreground or sent to the background. Senario: – The current task has four activities in its stack — three under the current activity. – The user presses the HOME key, goes to the application launcher, and selects a new application (actually, a new task). – The current task goes into the background and the root activity for the new task is displayed. Then, after a short period, the user goes back to the home screen and again selects the previous application (the previous task). – That task, with all four activities in the stack, comes forward. When the user presses the BACK key, the screen does not display the activity the user just left (the root activity of the previous task). Rather, the activity on the top of the stack is removed and the previous activity in the same task is displayed. • The behavior just described is the default behavior for activities and tasks. But there are ways to modify almost all aspects of it. The association of activities with tasks, and the behavior of an activity within a task, is controlled by the interaction between flags set in the Intent object that started the activity and attributes set in the activity's

Intent Flags The principal Intent flags are: • FLAG_ACTIVITY_NEW_TASK • FLAG_ACTIVITY_CLEAR_TOP • FLAG_ACTIVITY_RESET_TASK_IF_NEEDED • FLAG_ACTIVITY_SINGLE_TOP The principal

Intent Flags The principal Intent flags are: • FLAG_ACTIVITY_NEW_TASK • FLAG_ACTIVITY_CLEAR_TOP • FLAG_ACTIVITY_RESET_TASK_IF_NEEDED • FLAG_ACTIVITY_SINGLE_TOP The principal

Affinities and New Tasks • By default, all the activities in an application have an affinity for each other — that is, there's a preference for them all to belong to the same task. • An individual affinity can be set for each activity with the task. Affinity attribute of the

Affinities and New Tasks • By default, all the activities in an application have an affinity for each other — that is, there's a preference for them all to belong to the same task. • An individual affinity can be set for each activity with the task. Affinity attribute of the

FLAG_ACTIVITY_NEW_TASK • A new activity is, by default, launched into the task of the activity that called start. Activity(). It's pushed onto the same stack as the caller. • If the Intent object passed to start. Activity() contains the FLAG_ACTIVITY_NEW_TASK flag, the system looks for a different task to house the new activity. Often, as the name of the flag implies, it's a new task. However, it doesn't have to be. • If there's already an existing task with the same affinity as the new activity, the activity is launched into that task. If not, it begins a new task.

FLAG_ACTIVITY_NEW_TASK • A new activity is, by default, launched into the task of the activity that called start. Activity(). It's pushed onto the same stack as the caller. • If the Intent object passed to start. Activity() contains the FLAG_ACTIVITY_NEW_TASK flag, the system looks for a different task to house the new activity. Often, as the name of the flag implies, it's a new task. However, it doesn't have to be. • If there's already an existing task with the same affinity as the new activity, the activity is launched into that task. If not, it begins a new task.

allow. Task. Reparenting Attribute • If an activity has its allow. Task. Reparenting attribute set to "true", it can move from the task it starts in to the task it has an affinity for when that task comes to the fore. • Scenario: – An activity that reports weather conditions in selected cities is defined as part of a travel application. It has the same affinity as other activities in the same application (the default affinity) and it allows reparenting. – One of your activities starts the weather reporter, so it initially belongs to the same task as your activity. However, when the travel application next comes forward, the weather reporter will be reassigned to and displayed with that task. – If an. apk file contains more than one "application" from the user's point of view, you will probably want to assign different affinities to the activities associated with each of them.

allow. Task. Reparenting Attribute • If an activity has its allow. Task. Reparenting attribute set to "true", it can move from the task it starts in to the task it has an affinity for when that task comes to the fore. • Scenario: – An activity that reports weather conditions in selected cities is defined as part of a travel application. It has the same affinity as other activities in the same application (the default affinity) and it allows reparenting. – One of your activities starts the weather reporter, so it initially belongs to the same task as your activity. However, when the travel application next comes forward, the weather reporter will be reassigned to and displayed with that task. – If an. apk file contains more than one "application" from the user's point of view, you will probably want to assign different affinities to the activities associated with each of them.

Launch modes • There are four different launch modes that can be assigned to an

Launch modes • There are four different launch modes that can be assigned to an

Launch modes The modes differ from each other on these four points: • Which task will hold the activity that responds to the intent. For the "standard" and "single. Top" modes, it's the task that originated the intent (and called start. Activity()) — unless the Intent object contains the FLAG_ACTIVITY_NEW_TASK flag. In that case, a different task is chosen. In contrast, the "single. Task" and "single. Instance" modes mark activities that are always at the root of a task. They define a task; they're never launched into another task. • Whethere can be multiple instances of the activity. A "standard" or "single. Top" activity can be instantiated many times. They can belong to multiple tasks, and a given task can have multiple instances of the same activity. In contrast, "single. Task" and "single. Instance" activities are limited to just one instance. Since these activities are at the root of a task, this limitation means that there is never more than a single instance of the task on the device at one time.

Launch modes The modes differ from each other on these four points: • Which task will hold the activity that responds to the intent. For the "standard" and "single. Top" modes, it's the task that originated the intent (and called start. Activity()) — unless the Intent object contains the FLAG_ACTIVITY_NEW_TASK flag. In that case, a different task is chosen. In contrast, the "single. Task" and "single. Instance" modes mark activities that are always at the root of a task. They define a task; they're never launched into another task. • Whethere can be multiple instances of the activity. A "standard" or "single. Top" activity can be instantiated many times. They can belong to multiple tasks, and a given task can have multiple instances of the same activity. In contrast, "single. Task" and "single. Instance" activities are limited to just one instance. Since these activities are at the root of a task, this limitation means that there is never more than a single instance of the task on the device at one time.

Launch modes • Whether the instance can have other activities in its task. A "single. Instance" activity stands alone as the only activity in its task. If it starts another activity, that activity will be launched into a different task regardless of its launch mode — as if FLAG_ACTIVITY_NEW_TASK was in the intent. In all other respects, the "single. Instance" mode is identical to "single. Task". The other three modes permit multiple activities to belong to the task. A "single. Task" activity will always be the root activity of the task, but it can start other activities that will be assigned to its task. Instances of "standard" and "single. Top" activities can appear anywhere in a stack.

Launch modes • Whether the instance can have other activities in its task. A "single. Instance" activity stands alone as the only activity in its task. If it starts another activity, that activity will be launched into a different task regardless of its launch mode — as if FLAG_ACTIVITY_NEW_TASK was in the intent. In all other respects, the "single. Instance" mode is identical to "single. Task". The other three modes permit multiple activities to belong to the task. A "single. Task" activity will always be the root activity of the task, but it can start other activities that will be assigned to its task. Instances of "standard" and "single. Top" activities can appear anywhere in a stack.

Launch modes • • • Whether a new instance of the class will be launched to handle a new intent. For the default "standard" mode, a new instance is created to respond to every new intent. Each instance handles just one intent. For the "single. Top" mode, an existing instance of the class is re-used to handle a new intent if it resides at the top of the activity stack of the target task. If it does not reside at the top, it is not re-used. Instead, a new instance is created for the new intent and pushed on the stack. For example, suppose a task's activity stack consists of root activity A with activities B, C, and D on top in that order, so the stack is A-B-C-D. An intent arrives for an activity of type D. If D has the default "standard" launch mode, a new instance of the class is launched and the stack becomes A-B-C-D-D. However, if D's launch mode is "single. Top", the existing instance is expected to handle the new intent (since it's at the top of the stack) and the stack remains A-B-C-D. If, on the other hand, the arriving intent is for an activity of type B, a new instance of B would be launched no matter whether B's mode is "standard" or "single. Top" (since B is not at the top of the stack), so the resulting stack would be A-B-C-D-B.

Launch modes • • • Whether a new instance of the class will be launched to handle a new intent. For the default "standard" mode, a new instance is created to respond to every new intent. Each instance handles just one intent. For the "single. Top" mode, an existing instance of the class is re-used to handle a new intent if it resides at the top of the activity stack of the target task. If it does not reside at the top, it is not re-used. Instead, a new instance is created for the new intent and pushed on the stack. For example, suppose a task's activity stack consists of root activity A with activities B, C, and D on top in that order, so the stack is A-B-C-D. An intent arrives for an activity of type D. If D has the default "standard" launch mode, a new instance of the class is launched and the stack becomes A-B-C-D-D. However, if D's launch mode is "single. Top", the existing instance is expected to handle the new intent (since it's at the top of the stack) and the stack remains A-B-C-D. If, on the other hand, the arriving intent is for an activity of type B, a new instance of B would be launched no matter whether B's mode is "standard" or "single. Top" (since B is not at the top of the stack), so the resulting stack would be A-B-C-D-B.

Launch modes • There's never more than one instance of a "single. Task" or "single. Instance" activity, so that instance is expected to handle all new intents. A "single. Instance" activity is always at the top of the stack (since it is the only activity in the task), so it is always in position to handle the intent. • A "single. Task" activity may or may not have other activities above it in the stack. If it does, it is not in position to handle the intent, and the intent is dropped. (Even though the intent is dropped, its arrival would have caused the task to come to the foreground, where it would remain. ) • When an existing activity is asked to handle a new intent, the Intent object is passed to the activity in an on. New. Intent() call. (The intent object that originally started the activity can be retrieved by calling get. Intent(). ) • When a new instance of an Activity is created to handle a new intent, the user can always press the BACK key to return to the previous state (to the previous activity). But when an existing instance of an Activity handles a new intent, the user cannot press the BACK key to return to what that instance was doing before the new intent arrived.

Launch modes • There's never more than one instance of a "single. Task" or "single. Instance" activity, so that instance is expected to handle all new intents. A "single. Instance" activity is always at the top of the stack (since it is the only activity in the task), so it is always in position to handle the intent. • A "single. Task" activity may or may not have other activities above it in the stack. If it does, it is not in position to handle the intent, and the intent is dropped. (Even though the intent is dropped, its arrival would have caused the task to come to the foreground, where it would remain. ) • When an existing activity is asked to handle a new intent, the Intent object is passed to the activity in an on. New. Intent() call. (The intent object that originally started the activity can be retrieved by calling get. Intent(). ) • When a new instance of an Activity is created to handle a new intent, the user can always press the BACK key to return to the previous state (to the previous activity). But when an existing instance of an Activity handles a new intent, the user cannot press the BACK key to return to what that instance was doing before the new intent arrived.

Clearing the stack • If the user leaves a task for a long time, the system clears the task of all activities except the root activity. When the user returns to the task again, it's as the user left it, except that only the initial activity is present. • The idea is that, after a time, users will likely have abandoned what they were doing before and are returning to the task to begin something new.

Clearing the stack • If the user leaves a task for a long time, the system clears the task of all activities except the root activity. When the user returns to the task again, it's as the user left it, except that only the initial activity is present. • The idea is that, after a time, users will likely have abandoned what they were doing before and are returning to the task to begin something new.

Clearing the stack There are some activity attributes that can be used to control this behavior and modify it: • The always. Retain. Task. State attribute – If this attribute is set to "true" in the root activity of a task, the default behavior does not happen. The task retains all activities in its stack even after a long period. • The clear. Task. On. Launch attribute – If this attribute is set to "true" in the root activity of a task, the stack is cleared down to the root activity whenever the user leaves the task and returns to it. In other words, it's the polar opposite of always. Retain. Task. State. The user always returns to the task in its initial state, even after a momentary absence.

Clearing the stack There are some activity attributes that can be used to control this behavior and modify it: • The always. Retain. Task. State attribute – If this attribute is set to "true" in the root activity of a task, the default behavior does not happen. The task retains all activities in its stack even after a long period. • The clear. Task. On. Launch attribute – If this attribute is set to "true" in the root activity of a task, the stack is cleared down to the root activity whenever the user leaves the task and returns to it. In other words, it's the polar opposite of always. Retain. Task. State. The user always returns to the task in its initial state, even after a momentary absence.

Clearing the stack • The finish. On. Task. Launch attribute – This attribute is like clear. Task. On. Launch, but it operates on a single activity, not an entire task. And it can cause any activity to go away, including the root activity. When it's set to "true", the activity remains part of the task only for the current session. If the user leaves and then returns to the task, it no longer is present. • • There's another way to force activities to be removed from the stack. If an Intent object includes the FLAG_ACTIVITY_CLEAR_TOP flag, and the target task already has an instance of the type of activity that should handle the intent in its stack, all activities above that instance are cleared away so that it stands at the top of the stack and can respond to the intent. If the launch mode of the designated activity is "standard", it too will be removed from the stack, and a new instance will be launched to handle the incoming intent. That's because a new instance is always created for a new intent when the launch mode is "standard". FLAG_ACTIVITY_CLEAR_TOP is most often used in conjunction with FLAG_ACTIVITY_NEW_TASK. When used together, these flags are a way of locating an existing activity in another task and putting it in a position where it can respond to the intent.

Clearing the stack • The finish. On. Task. Launch attribute – This attribute is like clear. Task. On. Launch, but it operates on a single activity, not an entire task. And it can cause any activity to go away, including the root activity. When it's set to "true", the activity remains part of the task only for the current session. If the user leaves and then returns to the task, it no longer is present. • • There's another way to force activities to be removed from the stack. If an Intent object includes the FLAG_ACTIVITY_CLEAR_TOP flag, and the target task already has an instance of the type of activity that should handle the intent in its stack, all activities above that instance are cleared away so that it stands at the top of the stack and can respond to the intent. If the launch mode of the designated activity is "standard", it too will be removed from the stack, and a new instance will be launched to handle the incoming intent. That's because a new instance is always created for a new intent when the launch mode is "standard". FLAG_ACTIVITY_CLEAR_TOP is most often used in conjunction with FLAG_ACTIVITY_NEW_TASK. When used together, these flags are a way of locating an existing activity in another task and putting it in a position where it can respond to the intent.

Starting tasks • An activity is set up as the entry point for a task by giving it an intent filter with "android. intent. action. MAIN" as the specified action and "android. intent. category. LAUNCHER" as the specified category. • A filter of this kind causes an icon and label for the activity to be displayed in the application launcher, giving users a way both to launch the task and to return to it at any time after it has been launched.

Starting tasks • An activity is set up as the entry point for a task by giving it an intent filter with "android. intent. action. MAIN" as the specified action and "android. intent. category. LAUNCHER" as the specified category. • A filter of this kind causes an icon and label for the activity to be displayed in the application launcher, giving users a way both to launch the task and to return to it at any time after it has been launched.

Starting tasks • Icon access is important: Users must be able to leave a task and then come back to it later. • For this reason, the two launch modes that mark activities as always initiating a task, "single. Task" and "single. Instance", should be used only when the activity has a MAIN and LAUNCHER filter. • Scenario - Assume the filter is missing : – An intent launches a "single. Task" activity, initiating a new task, and the user spends some time working in that task. – The user then presses the HOME key. – The task is now ordered behind and obscured by the home screen. Because it is not represented in the application launcher, the user has no way to return to it.

Starting tasks • Icon access is important: Users must be able to leave a task and then come back to it later. • For this reason, the two launch modes that mark activities as always initiating a task, "single. Task" and "single. Instance", should be used only when the activity has a MAIN and LAUNCHER filter. • Scenario - Assume the filter is missing : – An intent launches a "single. Task" activity, initiating a new task, and the user spends some time working in that task. – The user then presses the HOME key. – The task is now ordered behind and obscured by the home screen. Because it is not represented in the application launcher, the user has no way to return to it.

Starting tasks • A similar difficulty attends the FLAG_ACTIVITY_NEW_TASK flag. If this flag causes an activity to begin a new task and the user presses the HOME key to leave it, there must be some way for the user to navigate back to it again. Some entities (such as the notification manager) always start activities in an external task, never as part of their own, so they always put FLAG_ACTIVITY_NEW_TASK in the intents they pass to start. Activity(). If you have an activity that can be invoked by an external entity that might use this flag, take care that the user has a independent way to get back to the task that's started. • For those cases where you don't want the user to be able to return to an activity, set the

Starting tasks • A similar difficulty attends the FLAG_ACTIVITY_NEW_TASK flag. If this flag causes an activity to begin a new task and the user presses the HOME key to leave it, there must be some way for the user to navigate back to it again. Some entities (such as the notification manager) always start activities in an external task, never as part of their own, so they always put FLAG_ACTIVITY_NEW_TASK in the intents they pass to start. Activity(). If you have an activity that can be invoked by an external entity that might use this flag, take care that the user has a independent way to get back to the task that's started. • For those cases where you don't want the user to be able to return to an activity, set the

Processes and Threads • When the first of an application's components needs to be run, Android starts a Linux process for it with a single thread of execution. • By default, all components of the application run in that process and thread. • You can arrange for components to run in other processes. • You can spawn additional threads for any process.

Processes and Threads • When the first of an application's components needs to be run, Android starts a Linux process for it with a single thread of execution. • By default, all components of the application run in that process and thread. • You can arrange for components to run in other processes. • You can spawn additional threads for any process.

Processes • The process where a component runs is controlled by the manifest file. • The component elements —

Processes • The process where a component runs is controlled by the manifest file. • The component elements —

Processes • All components are instantiated in the main thread of the specified process, and system calls to the component are dispatched from that thread. Separate threads are not created for each instance. • No component should perform long or blocking operations (such as networking operations or computation loops) when called by the system, since this will block any other components also in the process. • You can spawn separate threads for long operations.

Processes • All components are instantiated in the main thread of the specified process, and system calls to the component are dispatched from that thread. Separate threads are not created for each instance. • No component should perform long or blocking operations (such as networking operations or computation loops) when called by the system, since this will block any other components also in the process. • You can spawn separate threads for long operations.

Processes • Android may decide to shut down a process at some point, when memory is low and required by other processes that are more immediately serving the user. • Application components running in the process are consequently destroyed. • A process is restarted for those components when there's again work for them to do.

Processes • Android may decide to shut down a process at some point, when memory is low and required by other processes that are more immediately serving the user. • Application components running in the process are consequently destroyed. • A process is restarted for those components when there's again work for them to do.

Processes • When deciding which processes to terminate, Android weighs their relative importance to the user. • For example, it more readily shuts down a process with activities that are no longer visible on screen than a process with visible activities. • The decision whether to terminate a process, therefore, depends on the state of the components running in that process.

Processes • When deciding which processes to terminate, Android weighs their relative importance to the user. • For example, it more readily shuts down a process with activities that are no longer visible on screen than a process with visible activities. • The decision whether to terminate a process, therefore, depends on the state of the components running in that process.

Threads • There will likely be times when you will need to spawn a thread to do some background work. • Since the user interface must always be quick to respond to user actions, the thread that hosts an activity should not also host time-consuming operations like network downloads. • Anything that may not be completed quickly should be assigned to a different thread.

Threads • There will likely be times when you will need to spawn a thread to do some background work. • Since the user interface must always be quick to respond to user actions, the thread that hosts an activity should not also host time-consuming operations like network downloads. • Anything that may not be completed quickly should be assigned to a different thread.

Threads • Threads are created in code using standard Java Thread objects. • Android provides a number of convenience classes for managing threads: – Looper for running a message loop within a thread, – Handler for processing messages – Handler. Thread for setting up a thread with a message loop.

Threads • Threads are created in code using standard Java Thread objects. • Android provides a number of convenience classes for managing threads: – Looper for running a message loop within a thread, – Handler for processing messages – Handler. Thread for setting up a thread with a message loop.

Component Lifecycles • Application components have a lifecycle — a beginning when Android instantiates them to respond to intents through to an end when the instances are destroyed. • In between, they may sometimes be active or inactive, or, in the case of activities, visible to the user or invisible.

Component Lifecycles • Application components have a lifecycle — a beginning when Android instantiates them to respond to intents through to an end when the instances are destroyed. • In between, they may sometimes be active or inactive, or, in the case of activities, visible to the user or invisible.

Component Lifecycles - Active • An activity has essentially three states: 1) It is active or running when it is in the foreground of the screen (at the top of the activity stack for the current task). This is the activity that is the focus for the user's actions.

Component Lifecycles - Active • An activity has essentially three states: 1) It is active or running when it is in the foreground of the screen (at the top of the activity stack for the current task). This is the activity that is the focus for the user's actions.

Component Lifecycles - Paused • An activity has essentially three states: 2) It is paused if it has lost focus but is still visible to the user. That is, another activity lies on top of it and that activity either is transparent or doesn't cover the full screen, so some of the paused activity can show through. A paused activity is completely alive (it maintains all state and member information and remains attached to the window manager), but can be killed by the system in extreme low memory situations.

Component Lifecycles - Paused • An activity has essentially three states: 2) It is paused if it has lost focus but is still visible to the user. That is, another activity lies on top of it and that activity either is transparent or doesn't cover the full screen, so some of the paused activity can show through. A paused activity is completely alive (it maintains all state and member information and remains attached to the window manager), but can be killed by the system in extreme low memory situations.

Component Lifecycles - Paused • An activity has essentially three states: 3) It is stopped if it is completely obscured by another activity. It still retains all state and member information. However, it is no longer visible to the user so its window is hidden and it will often be killed by the system when memory is needed elsewhere.

Component Lifecycles - Paused • An activity has essentially three states: 3) It is stopped if it is completely obscured by another activity. It still retains all state and member information. However, it is no longer visible to the user so its window is hidden and it will often be killed by the system when memory is needed elsewhere.

Component Lifecycles • If an activity is paused or stopped, the system can drop it from memory either by asking it to finish (calling its finish() method), or simply killing its process. When it is displayed again to the user, it must be completely restarted and restored to its previous state.

Component Lifecycles • If an activity is paused or stopped, the system can drop it from memory either by asking it to finish (calling its finish() method), or simply killing its process. When it is displayed again to the user, it must be completely restarted and restored to its previous state.

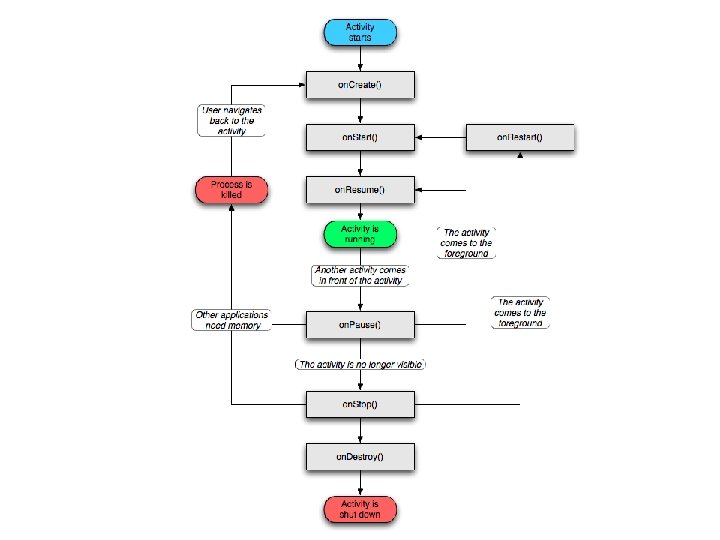

Lifecycles Notifications • As an activity transitions from state to state, it is notified of the change by calls to the following protected methods: • void on. Create(Bundle saved. Instance. State) void on. Start() void on. Resume() void on. Pause() void on. Stop() void on. Destroy()

Lifecycles Notifications • As an activity transitions from state to state, it is notified of the change by calls to the following protected methods: • void on. Create(Bundle saved. Instance. State) void on. Start() void on. Resume() void on. Pause() void on. Stop() void on. Destroy()

Lifecycles Notifications • All of these methods are hooks that you can override to do appropriate work when the state changes. • All activities must implement on. Create() to do the initial setup when the object is first instantiated. • Many will also implement on. Pause() to commit data changes and otherwise prepare to stop interacting with the user.

Lifecycles Notifications • All of these methods are hooks that you can override to do appropriate work when the state changes. • All activities must implement on. Create() to do the initial setup when the object is first instantiated. • Many will also implement on. Pause() to commit data changes and otherwise prepare to stop interacting with the user.

Activity Lifetime • The entire lifetime of an activity happens between the first call to on. Create() through to a single final call to on. Destroy(). • An activity does all its initial setup of "global" state in on. Create(), and releases all remaining resources in on. Destroy(). • For example, if it has a thread running in the background to download data from the network, it may create that thread in on. Create() and then stop the thread in on. Destroy().

Activity Lifetime • The entire lifetime of an activity happens between the first call to on. Create() through to a single final call to on. Destroy(). • An activity does all its initial setup of "global" state in on. Create(), and releases all remaining resources in on. Destroy(). • For example, if it has a thread running in the background to download data from the network, it may create that thread in on. Create() and then stop the thread in on. Destroy().

Visible Lifetime • The visible lifetime of an activity happens between a call to on. Start() until a corresponding call to on. Stop(). During this time, the user can see the activity on-screen, though it may not be in the foreground and interacting with the user. • Between these two methods, you can maintain resources that are needed to show the activity to the user. For example, you can register a Broadcast. Receiver in on. Start() to monitor for changes that impact your UI, and unregister it in on. Stop() when the user can no longer see what you are displaying. • The on. Start() and on. Stop() methods can be called multiple times, as the activity alternates between being visible and hidden to the user.

Visible Lifetime • The visible lifetime of an activity happens between a call to on. Start() until a corresponding call to on. Stop(). During this time, the user can see the activity on-screen, though it may not be in the foreground and interacting with the user. • Between these two methods, you can maintain resources that are needed to show the activity to the user. For example, you can register a Broadcast. Receiver in on. Start() to monitor for changes that impact your UI, and unregister it in on. Stop() when the user can no longer see what you are displaying. • The on. Start() and on. Stop() methods can be called multiple times, as the activity alternates between being visible and hidden to the user.

Foreground Lifetime • The foreground lifetime of an activity happens between a call to on. Resume() until a corresponding call to on. Pause(). • During this time, the activity is in front of all other activities on screen and is interacting with the user. • An activity can frequently transition between the resumed and paused states — for example, on. Pause() is called when the device goes to sleep or when a new activity is started, on. Resume() is called when an activity result or a new intent is delivered. • Therefore, the code in these two methods should be fairly lightweight.

Foreground Lifetime • The foreground lifetime of an activity happens between a call to on. Resume() until a corresponding call to on. Pause(). • During this time, the activity is in front of all other activities on screen and is interacting with the user. • An activity can frequently transition between the resumed and paused states — for example, on. Pause() is called when the device goes to sleep or when a new activity is started, on. Resume() is called when an activity result or a new intent is delivered. • Therefore, the code in these two methods should be fairly lightweight.

on. Create() • Called when the activity is first created. • This is where you should do all of your normal static set up — create views, bind data to lists, and so on. • Passed a Bundle object containing the activity's previous state, if that state was captured. • Always followed by on. Start(). • Not killable.

on. Create() • Called when the activity is first created. • This is where you should do all of your normal static set up — create views, bind data to lists, and so on. • Passed a Bundle object containing the activity's previous state, if that state was captured. • Always followed by on. Start(). • Not killable.

on. Restart() • Called after the activity has been stopped, just prior to it being started again. • Always followed by on. Start(). • Not killable.

on. Restart() • Called after the activity has been stopped, just prior to it being started again. • Always followed by on. Start(). • Not killable.

on. Resume() • Called just before the activity starts interacting with the user. At this point the activity is at the top of the activity stack, with user input going to it. • Always followed by on. Pause(). • Not killable.

on. Resume() • Called just before the activity starts interacting with the user. At this point the activity is at the top of the activity stack, with user input going to it. • Always followed by on. Pause(). • Not killable.

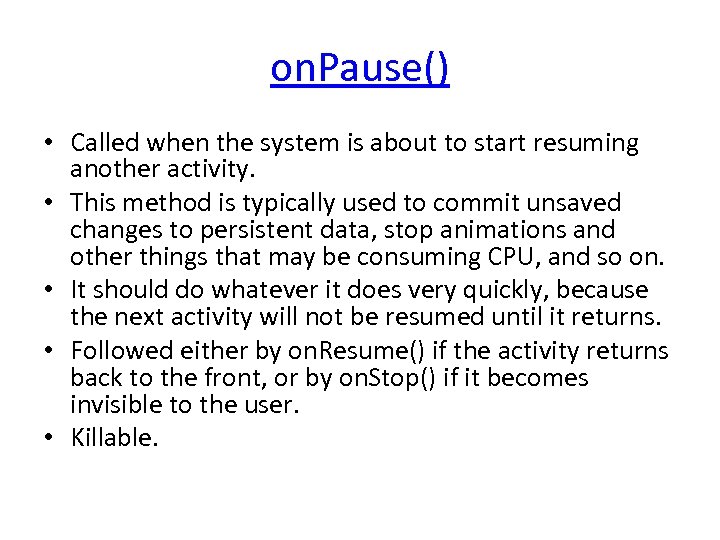

on. Pause() • Called when the system is about to start resuming another activity. • This method is typically used to commit unsaved changes to persistent data, stop animations and other things that may be consuming CPU, and so on. • It should do whatever it does very quickly, because the next activity will not be resumed until it returns. • Followed either by on. Resume() if the activity returns back to the front, or by on. Stop() if it becomes invisible to the user. • Killable.

on. Pause() • Called when the system is about to start resuming another activity. • This method is typically used to commit unsaved changes to persistent data, stop animations and other things that may be consuming CPU, and so on. • It should do whatever it does very quickly, because the next activity will not be resumed until it returns. • Followed either by on. Resume() if the activity returns back to the front, or by on. Stop() if it becomes invisible to the user. • Killable.

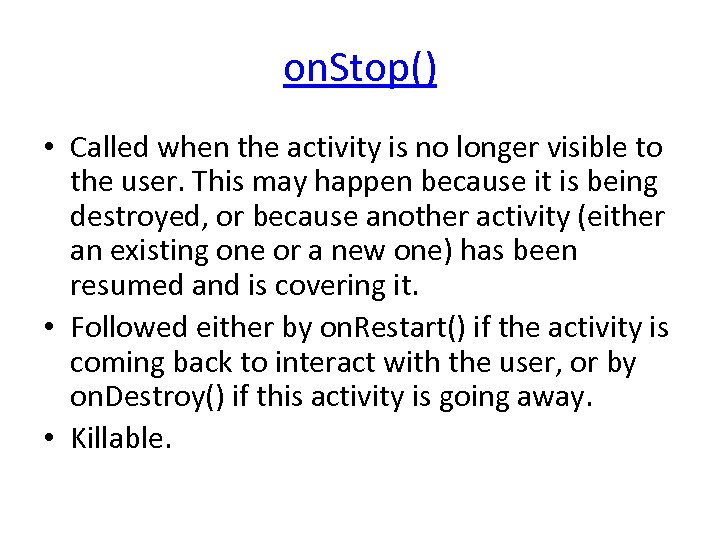

on. Stop() • Called when the activity is no longer visible to the user. This may happen because it is being destroyed, or because another activity (either an existing one or a new one) has been resumed and is covering it. • Followed either by on. Restart() if the activity is coming back to interact with the user, or by on. Destroy() if this activity is going away. • Killable.

on. Stop() • Called when the activity is no longer visible to the user. This may happen because it is being destroyed, or because another activity (either an existing one or a new one) has been resumed and is covering it. • Followed either by on. Restart() if the activity is coming back to interact with the user, or by on. Destroy() if this activity is going away. • Killable.

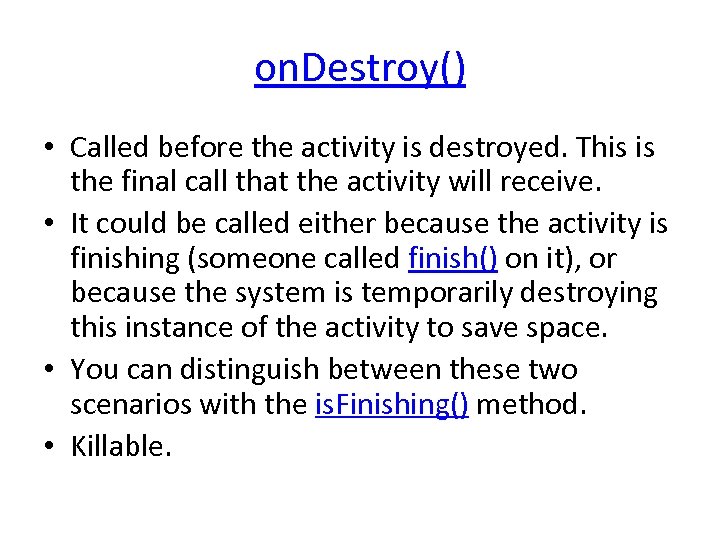

on. Destroy() • Called before the activity is destroyed. This is the final call that the activity will receive. • It could be called either because the activity is finishing (someone called finish() on it), or because the system is temporarily destroying this instance of the activity to save space. • You can distinguish between these two scenarios with the is. Finishing() method. • Killable.

on. Destroy() • Called before the activity is destroyed. This is the final call that the activity will receive. • It could be called either because the activity is finishing (someone called finish() on it), or because the system is temporarily destroying this instance of the activity to save space. • You can distinguish between these two scenarios with the is. Finishing() method. • Killable.

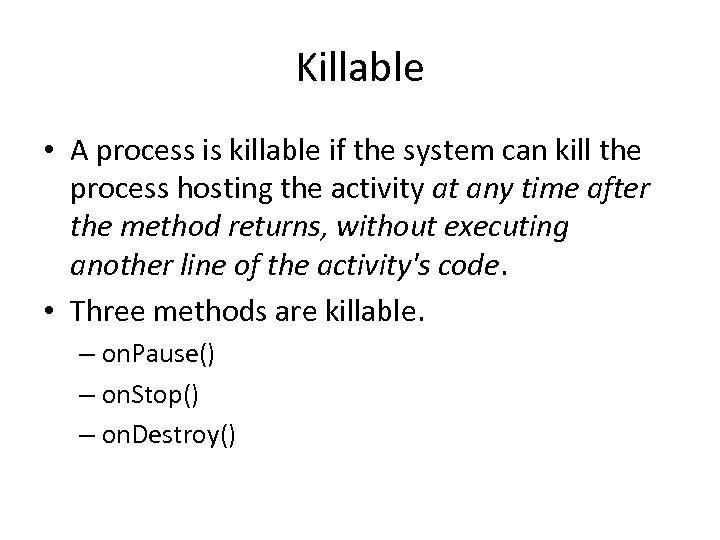

Killable • A process is killable if the system can kill the process hosting the activity at any time after the method returns, without executing another line of the activity's code. • Three methods are killable. – on. Pause() – on. Stop() – on. Destroy()

Killable • A process is killable if the system can kill the process hosting the activity at any time after the method returns, without executing another line of the activity's code. • Three methods are killable. – on. Pause() – on. Stop() – on. Destroy()

Killable • Because on. Pause() is the first of the three, it's the only one that's guaranteed to be called before the process is killed. • You should use on. Pause() to write any persistent data (such as user edits) to storage. • An activity is in a killable state from the time on. Pause() returns to the time on. Resume() is called. It will not again be killable until on. Pause() again returns. • An activity that's not technically "killable" by this definition might still be killed by the system — but that would happen only in extreme and dire circumstances when there is no other recourse.

Killable • Because on. Pause() is the first of the three, it's the only one that's guaranteed to be called before the process is killed. • You should use on. Pause() to write any persistent data (such as user edits) to storage. • An activity is in a killable state from the time on. Pause() returns to the time on. Resume() is called. It will not again be killable until on. Pause() again returns. • An activity that's not technically "killable" by this definition might still be killed by the system — but that would happen only in extreme and dire circumstances when there is no other recourse.

Saving activity state • When the system, rather than the user, shuts down an activity to conserve memory, the user may expect to return to the activity and find it in its previous state. • To capture that state you can implement an on. Save. Instance. State() method for the activity. • Android calls this method before making the activity vulnerable to being destroyed— that is, before on. Pause() is called.

Saving activity state • When the system, rather than the user, shuts down an activity to conserve memory, the user may expect to return to the activity and find it in its previous state. • To capture that state you can implement an on. Save. Instance. State() method for the activity. • Android calls this method before making the activity vulnerable to being destroyed— that is, before on. Pause() is called.

Saving activity state • Android passes the method a Bundle object where you can record the dynamic state of the activity as name-value pairs. • When the activity is again started, the Bundle is passed both to on. Create() and to a method that's called after on. Start(), on. Restore. Instance. State(), so that either or both of them can recreate the captured state. • Methods on. Save. Instance. State() and on. Restore. Instance. State() are not lifecycle methods. They are not always called.

Saving activity state • Android passes the method a Bundle object where you can record the dynamic state of the activity as name-value pairs. • When the activity is again started, the Bundle is passed both to on. Create() and to a method that's called after on. Start(), on. Restore. Instance. State(), so that either or both of them can recreate the captured state. • Methods on. Save. Instance. State() and on. Restore. Instance. State() are not lifecycle methods. They are not always called.