6d80a9a7188ff89a59752fefd3027bf1.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 18

Andreas A. Jobst Monetary and Capital Markets Dept. International Monetary Fund (IMF) Sukuk – Quo Vadis? Islamic Securitization After the Subprime Crisis 700 19 th Street, NW, Washington, DC 20431, USA E-mail: ajobst@imf. org © A. Jobst, 2008

Overview 1. Macroeconomic Situation and Effect on Islamic capital market instruments 2. Developments of the Sukuk Market 3. Islamic Securitization as the “Third Way” 4. Challenges and Outlook © A. Jobst, 2008

Monetary and Capital Markets Department © A. Jobst, 2008

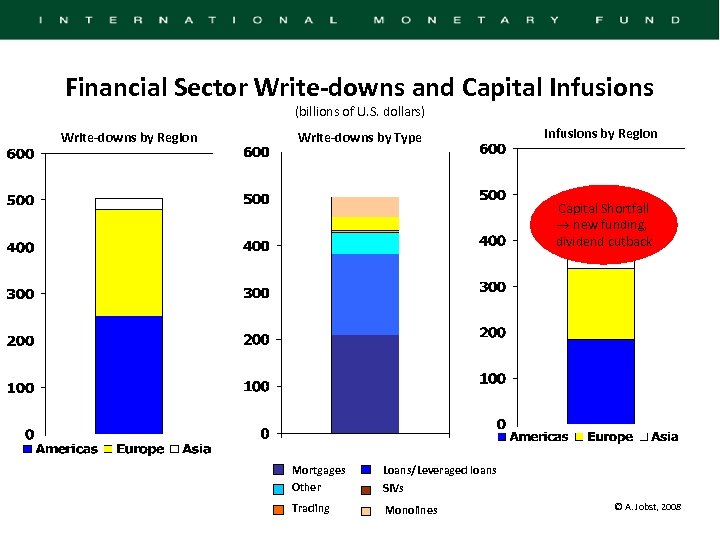

Financial Sector Write-downs and Capital Infusions (billions of U. S. dollars) Write-downs by Region Write-downs by Type Infusions by Region Capital Shortfall new funding, dividend cutback Mortgages Other Loans/Leveraged loans Trading Monolines SIVs © A. Jobst, 2008

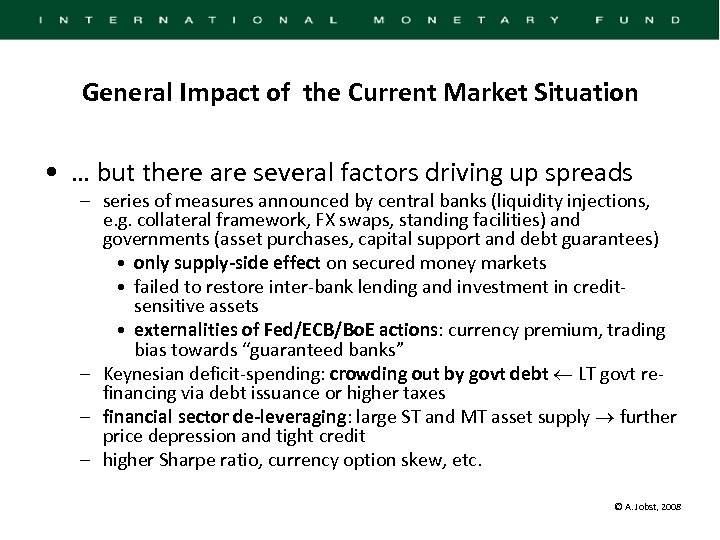

General Impact of the Current Market Situation • … but there are several factors driving up spreads – series of measures announced by central banks (liquidity injections, e. g. collateral framework, FX swaps, standing facilities) and governments (asset purchases, capital support and debt guarantees) • only supply-side effect on secured money markets • failed to restore inter-bank lending and investment in creditsensitive assets • externalities of Fed/ECB/Bo. E actions: currency premium, trading bias towards “guaranteed banks” – Keynesian deficit-spending: crowding out by govt debt LT govt refinancing via debt issuance or higher taxes – financial sector de-leveraging: large ST and MT asset supply further price depression and tight credit – higher Sharpe ratio, currency option skew, etc. © A. Jobst, 2008

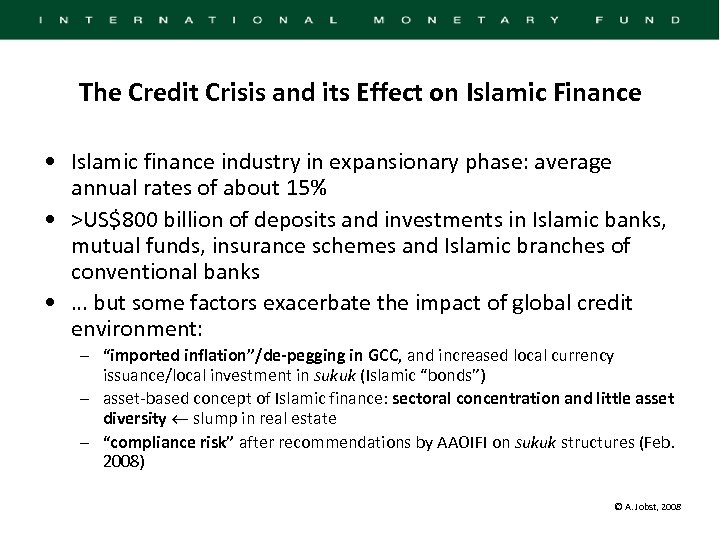

The Credit Crisis and its Effect on Islamic Finance • Islamic finance industry in expansionary phase: average annual rates of about 15% • >US$800 billion of deposits and investments in Islamic banks, mutual funds, insurance schemes and Islamic branches of conventional banks • … but some factors exacerbate the impact of global credit environment: – “imported inflation”/de-pegging in GCC, and increased local currency issuance/local investment in sukuk (Islamic “bonds”) – asset-based concept of Islamic finance: sectoral concentration and little asset diversity slump in real estate – “compliance risk” after recommendations by AAOIFI on sukuk structures (Feb. 2008) © A. Jobst, 2008

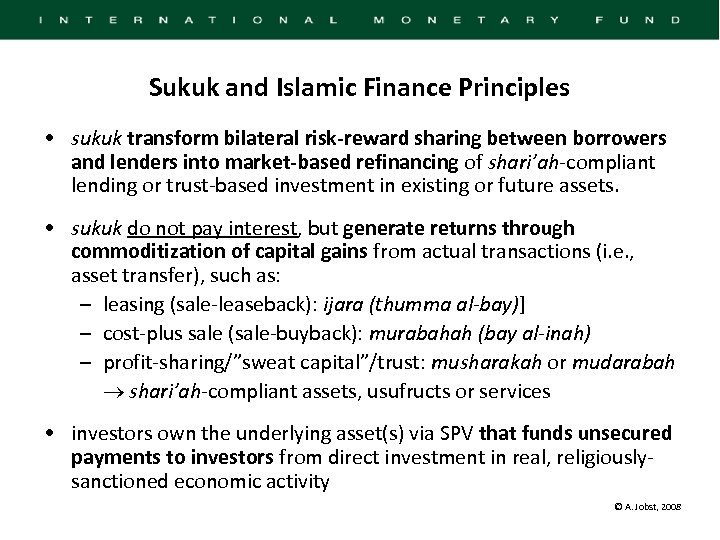

Sukuk and Islamic Finance Principles • sukuk transform bilateral risk-reward sharing between borrowers and lenders into market-based refinancing of shari’ah-compliant lending or trust-based investment in existing or future assets. • sukuk do not pay interest, but generate returns through commoditization of capital gains from actual transactions (i. e. , asset transfer), such as: – leasing (sale-leaseback): ijara (thumma al-bay)] – cost-plus sale (sale-buyback): murabahah (bay al-inah) – profit-sharing/”sweat capital”/trust: musharakah or mudarabah shari’ah-compliant assets, usufructs or services • investors own the underlying asset(s) via SPV that funds unsecured payments to investors from direct investment in real, religiouslysanctioned economic activity © A. Jobst, 2008

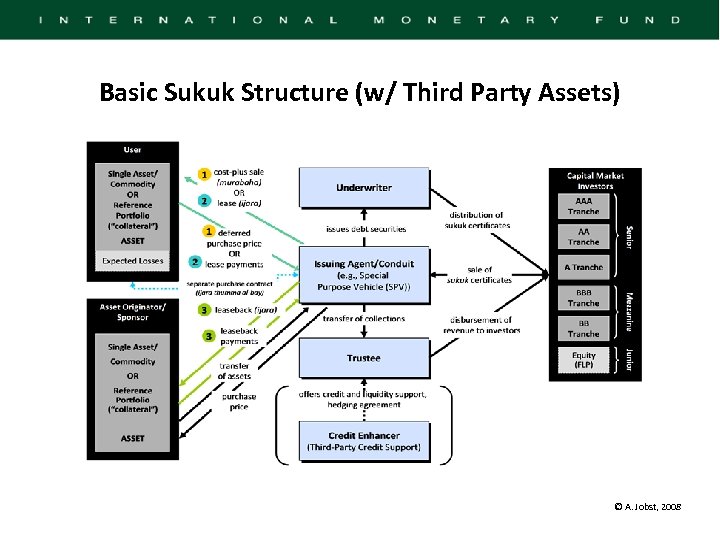

Basic Sukuk Structure (w/ Third Party Assets) © A. Jobst, 2008

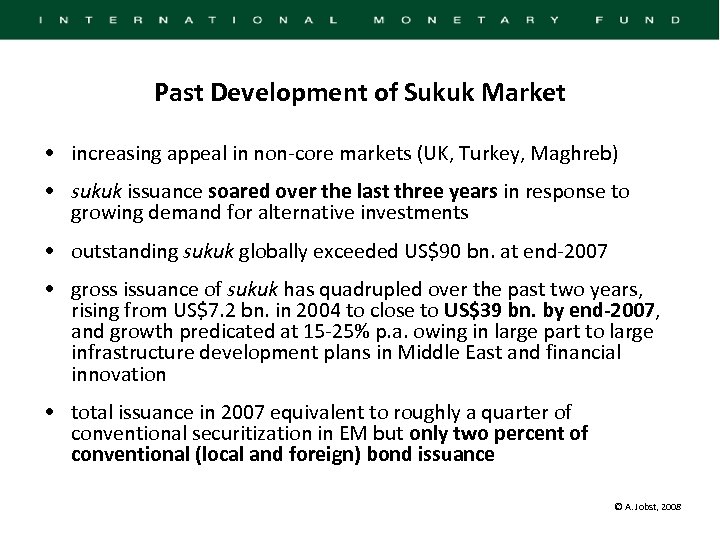

Past Development of Sukuk Market • increasing appeal in non-core markets (UK, Turkey, Maghreb) • sukuk issuance soared over the last three years in response to growing demand for alternative investments • outstanding sukuk globally exceeded US$90 bn. at end-2007 • gross issuance of sukuk has quadrupled over the past two years, rising from US$7. 2 bn. in 2004 to close to US$39 bn. by end-2007, and growth predicated at 15 -25% p. a. owing in large part to large infrastructure development plans in Middle East and financial innovation • total issuance in 2007 equivalent to roughly a quarter of conventional securitization in EM but only two percent of conventional (local and foreign) bond issuance © A. Jobst, 2008

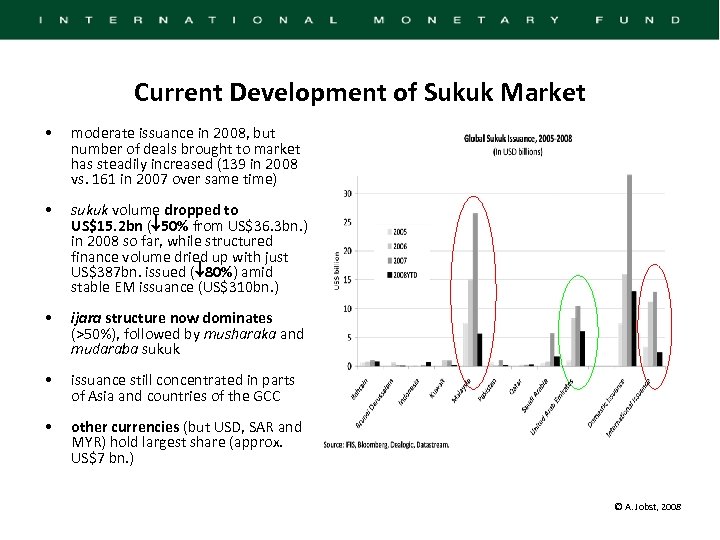

Current Development of Sukuk Market • moderate issuance in 2008, but number of deals brought to market has steadily increased (139 in 2008 vs. 161 in 2007 over same time) • sukuk volume dropped to US$15. 2 bn ( 50% from US$36. 3 bn. ) in 2008 so far, while structured finance volume dried up with just US$387 bn. issued ( 80%) amid stable EM issuance (US$310 bn. ) • ijara structure now dominates (>50%), followed by musharaka and mudaraba sukuk • issuance still concentrated in parts of Asia and countries of the GCC • other currencies (but USD, SAR and MYR) hold largest share (approx. US$7 bn. ) © A. Jobst, 2008

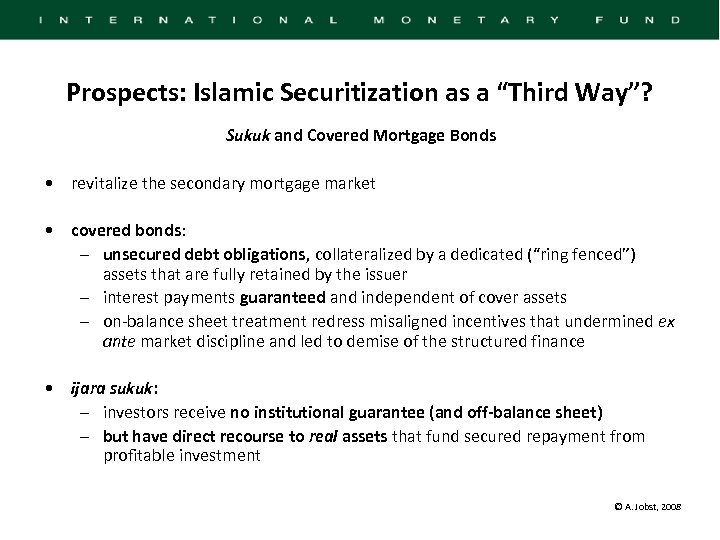

Prospects: Islamic Securitization as a “Third Way”? Sukuk and Covered Mortgage Bonds • revitalize the secondary mortgage market • covered bonds: – unsecured debt obligations, collateralized by a dedicated (“ring fenced”) assets that are fully retained by the issuer – interest payments guaranteed and independent of cover assets – on-balance sheet treatment redress misaligned incentives that undermined ex ante market discipline and led to demise of the structured finance • ijara sukuk: – investors receive no institutional guarantee (and off-balance sheet) – but have direct recourse to real assets that fund secured repayment from profitable investment © A. Jobst, 2008

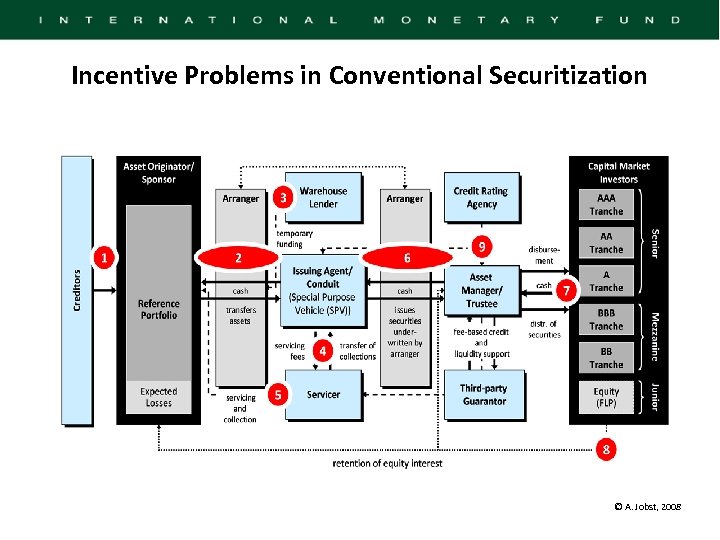

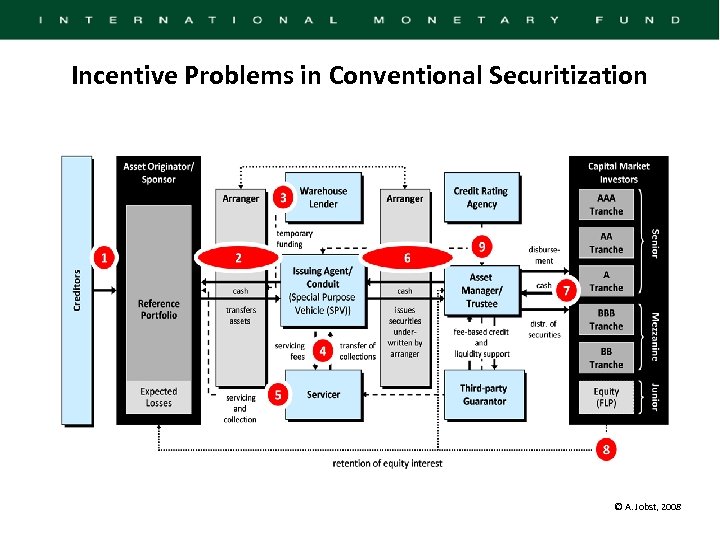

Incentive Problems in Conventional Securitization © A. Jobst, 2008

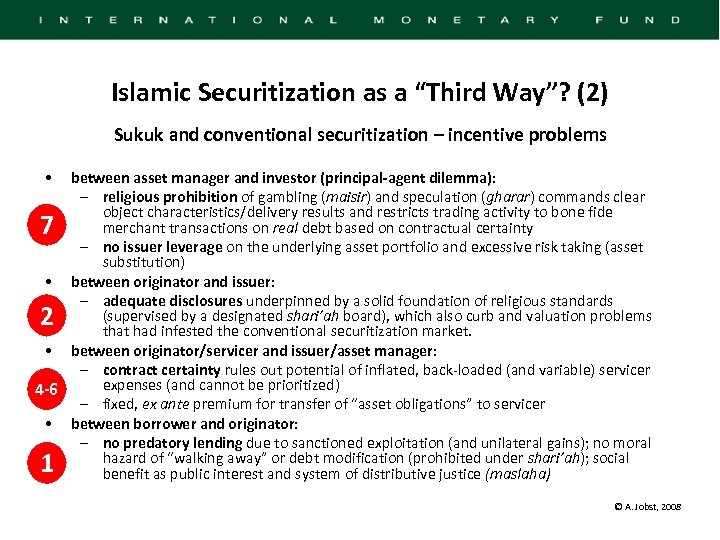

Islamic Securitization as a “Third Way”? (2) Sukuk and conventional securitization – incentive problems • between asset manager and investor (principal-agent dilemma): – religious prohibition of gambling (maisir) and speculation (gharar) commands clear object characteristics/delivery results and restricts trading activity to bone fide merchant transactions on real debt based on contractual certainty – no issuer leverage on the underlying asset portfolio and excessive risk taking (asset substitution) • between originator and issuer: – adequate disclosures underpinned by a solid foundation of religious standards (supervised by a designated shari’ah board), which also curb and valuation problems that had infested the conventional securitization market. • between originator/servicer and issuer/asset manager: – contract certainty rules out potential of inflated, back-loaded (and variable) servicer expenses (and cannot be prioritized) 4 -6 – fixed, ex ante premium for transfer of “asset obligations” to servicer • between borrower and originator: – no predatory lending due to sanctioned exploitation (and unilateral gains); no moral hazard of “walking away” or debt modification (prohibited under shari’ah); social benefit as public interest and system of distributive justice (maslaha) 7 2 1 © A. Jobst, 2008

Incentive Problems in Conventional Securitization © A. Jobst, 2008

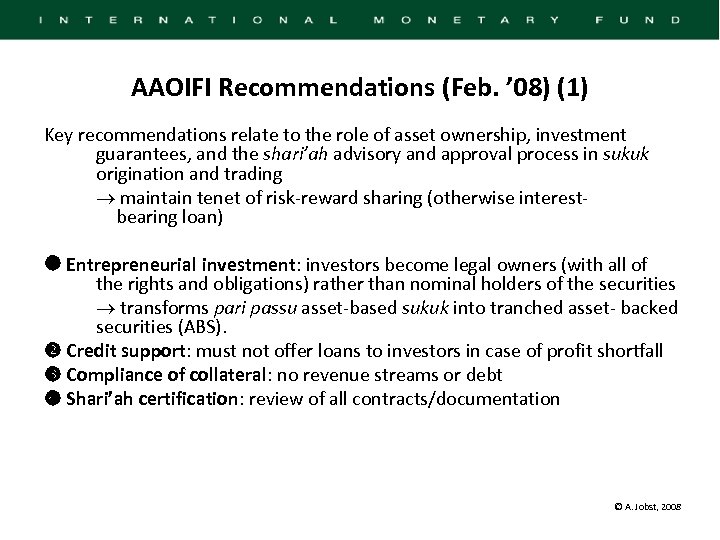

AAOIFI Recommendations (Feb. ’ 08) (1) Key recommendations relate to the role of asset ownership, investment guarantees, and the shari’ah advisory and approval process in sukuk origination and trading maintain tenet of risk-reward sharing (otherwise interestbearing loan) Entrepreneurial investment: investors become legal owners (with all of the rights and obligations) rather than nominal holders of the securities transforms pari passu asset-based sukuk into tranched asset- backed securities (ABS). Credit support: must not offer loans to investors in case of profit shortfall Compliance of collateral: no revenue streams or debt Shari’ah certification: review of all contracts/documentation © A. Jobst, 2008

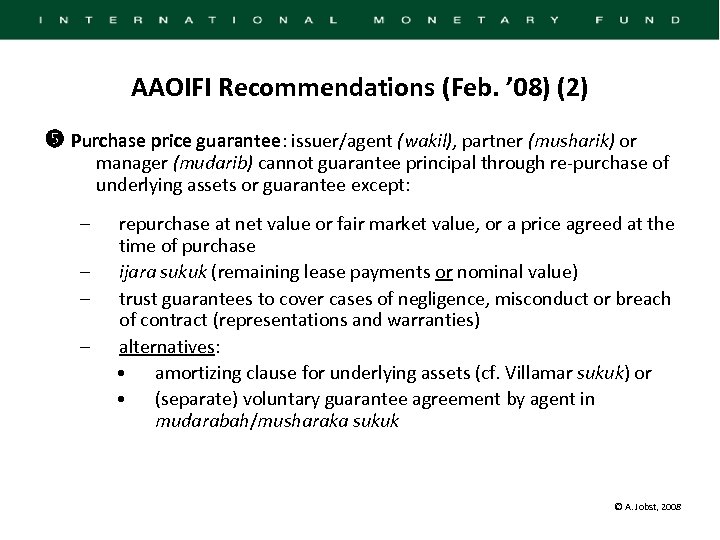

AAOIFI Recommendations (Feb. ’ 08) (2) Purchase price guarantee: issuer/agent (wakil), partner (musharik) or manager (mudarib) cannot guarantee principal through re-purchase of underlying assets or guarantee except: – – repurchase at net value or fair market value, or a price agreed at the time of purchase ijara sukuk (remaining lease payments or nominal value) trust guarantees to cover cases of negligence, misconduct or breach of contract (representations and warranties) alternatives: • amortizing clause for underlying assets (cf. Villamar sukuk) or • (separate) voluntary guarantee agreement by agent in mudarabah/musharaka sukuk © A. Jobst, 2008

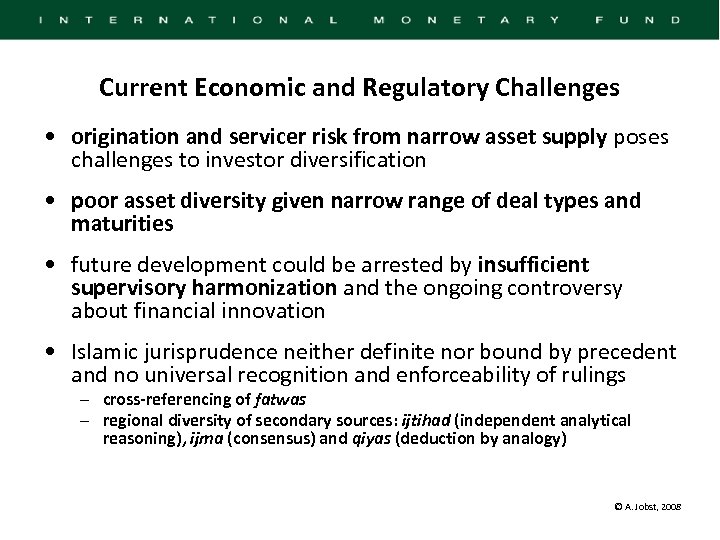

Current Economic and Regulatory Challenges • origination and servicer risk from narrow asset supply poses challenges to investor diversification • poor asset diversity given narrow range of deal types and maturities • future development could be arrested by insufficient supervisory harmonization and the ongoing controversy about financial innovation • Islamic jurisprudence neither definite nor bound by precedent and no universal recognition and enforceability of rulings – cross-referencing of fatwas – regional diversity of secondary sources: ijtihad (independent analytical reasoning), ijma (consensus) and qiyas (deduction by analogy) © A. Jobst, 2008

References Čihák, Martin and Heiko Hesse, 2008, “Islamic Banks and Financial Stability: An Empirical Analysis, ” IMF Working Paper 08/16 (Washington: International Monetary Fund). Hesse, Heiko, Andreas A. Jobst and Juan Solé, 2008, “Trends and Challenges in Islamic Finance, ” World Economics (April-June). Jobst, Andreas A. , Peter Kunzel, Paul Mills and Amadou Sy, 2008, “Islamic Bond Issuance – What Sovereign Debt Managers Need to Know, ” International Journal of Islamic & Middle East Finance and Management, Vol. 1, No. 4. Jobst, Andreas A. , 2007, “The Economics of Islamic Finance and Securitization, ” Journal of Structured Finance, Vol. 13, No. 1 (Spring), 1 -22. Solé, Juan, 2007, “Introducing Islamic Banks into Conventional Banking Systems”, IMF Working Paper 07/175 (Washington: International Monetary Fund). © A. Jobst, 2008

6d80a9a7188ff89a59752fefd3027bf1.ppt