9481bad83e5d5d0252d1f32b46daf835.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 99

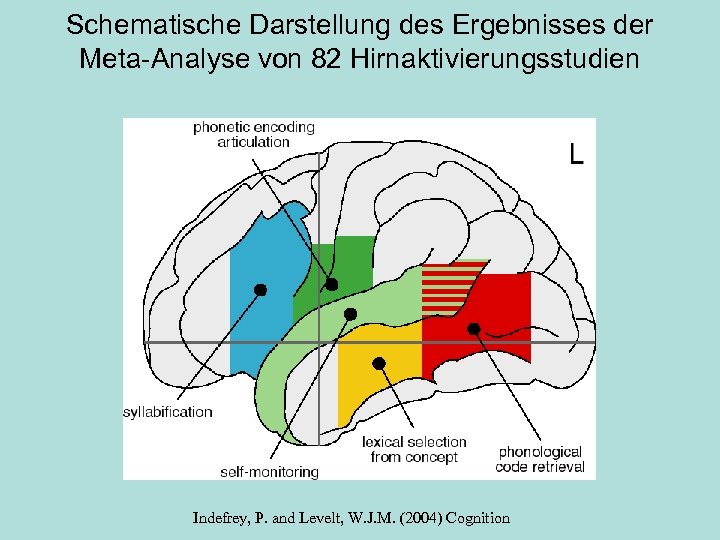

Analyse von 82 Hirnaktivierungsxperimenten mit vier verschiedenen Wortproduktionsaufgaben: l Bildbenennung l Wortgenerierung (z. B. Nennen Sie möglichst viele Tiere!) l Wortlesen (HUND) l Pseudowortlesen (HUNG)

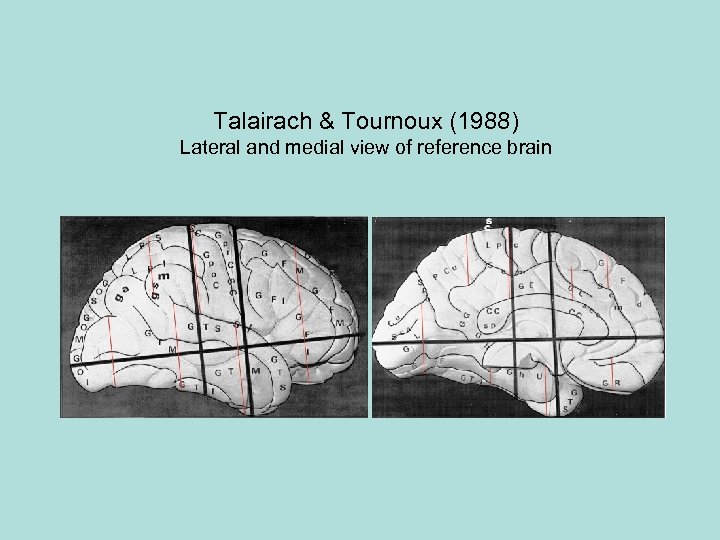

Talairach & Tournoux (1988) Lateral and medial view of reference brain

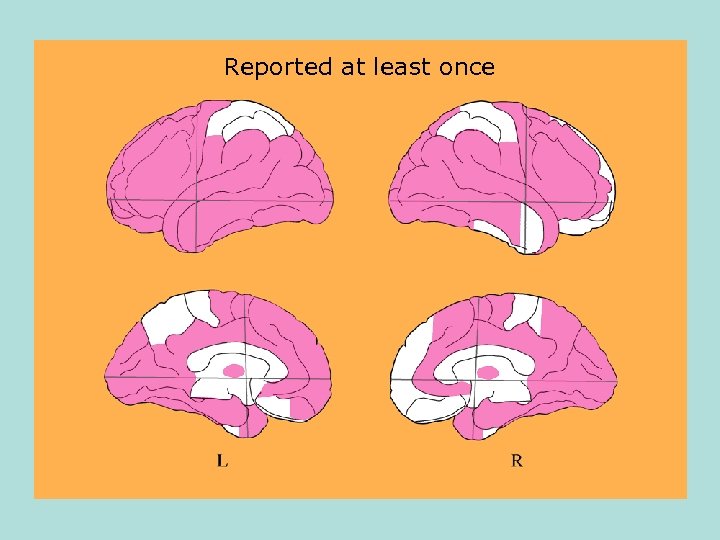

Reported at least once

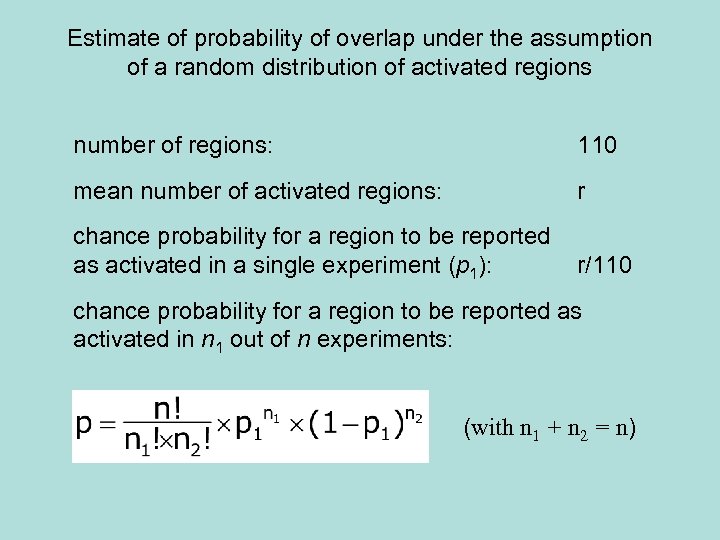

Estimate of probability of overlap under the assumption of a random distribution of activated regions number of regions: 110 mean number of activated regions: r chance probability for a region to be reported as activated in a single experiment (p 1): r/110 chance probability for a region to be reported as activated in n 1 out of n experiments: (with n 1 + n 2 = n)

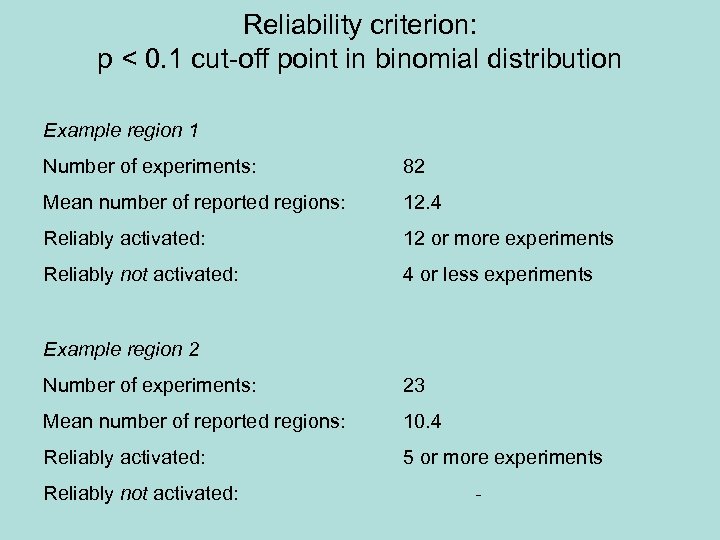

Reliability criterion: p < 0. 1 cut-off point in binomial distribution Example region 1 Number of experiments: 82 Mean number of reported regions: 12. 4 Reliably activated: 12 or more experiments Reliably not activated: 4 or less experiments Example region 2 Number of experiments: 23 Mean number of reported regions: 10. 4 Reliably activated: 5 or more experiments Reliably not activated: -

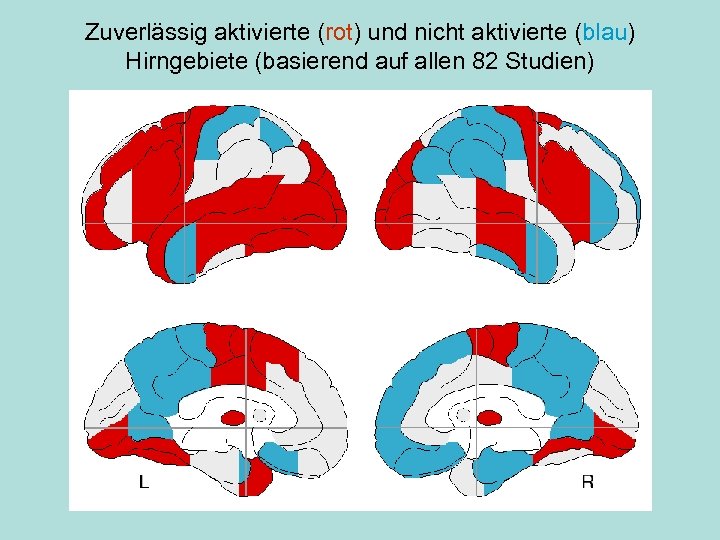

Zuverlässig aktivierte (rot) und nicht aktivierte (blau) Hirngebiete (basierend auf allen 82 Studien)

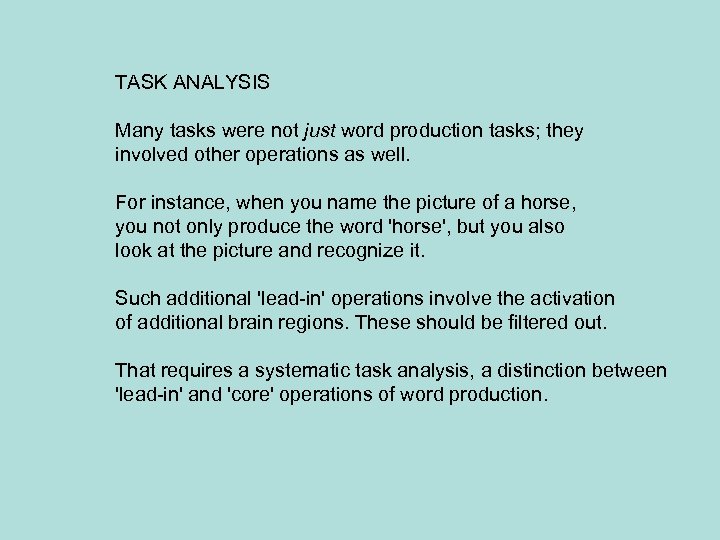

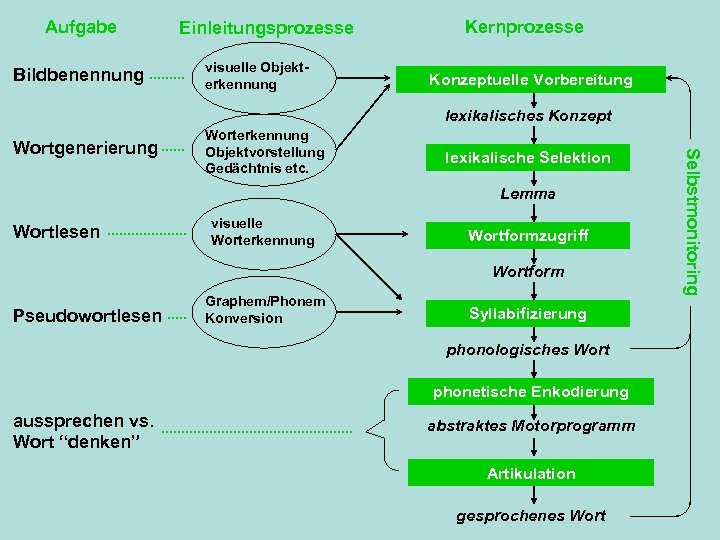

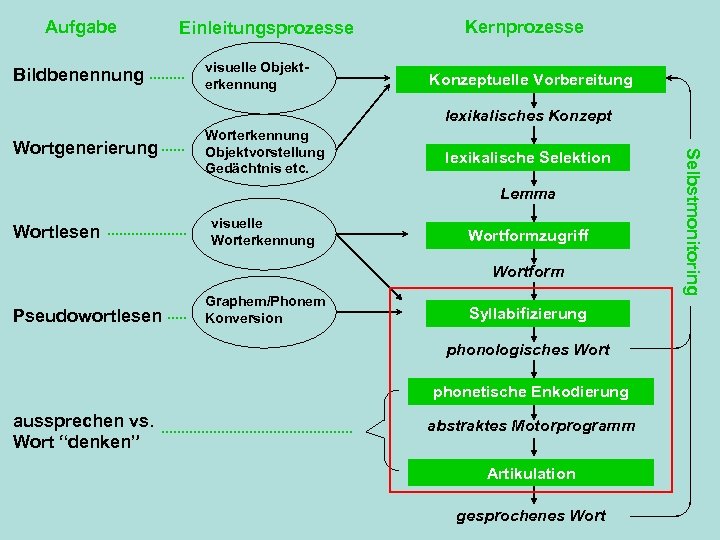

TASK ANALYSIS Many tasks were not just word production tasks; they involved other operations as well. For instance, when you name the picture of a horse, you not only produce the word 'horse', but you also look at the picture and recognize it. Such additional 'lead-in' operations involve the activation of additional brain regions. These should be filtered out. That requires a systematic task analysis, a distinction between 'lead-in' and 'core' operations of word production.

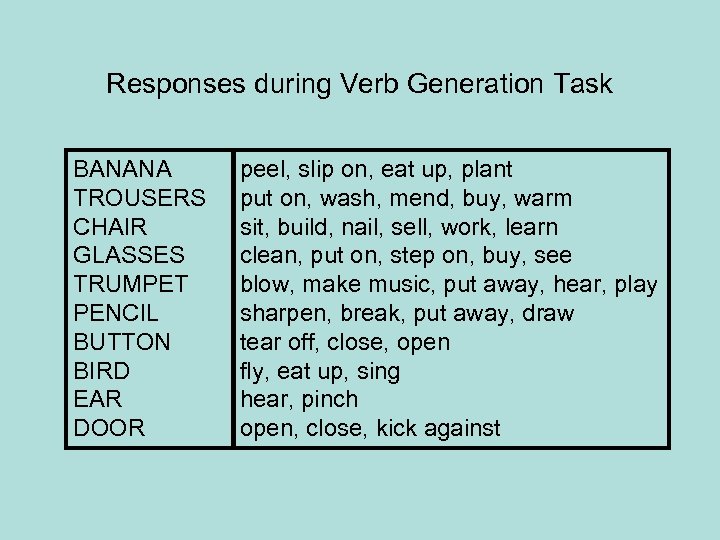

Responses during Verb Generation Task BANANA TROUSERS CHAIR GLASSES TRUMPET PENCIL BUTTON BIRD EAR DOOR peel, slip on, eat up, plant put on, wash, mend, buy, warm sit, build, nail, sell, work, learn clean, put on, step on, buy, see blow, make music, put away, hear, play sharpen, break, put away, draw tear off, close, open fly, eat up, sing hear, pinch open, close, kick against

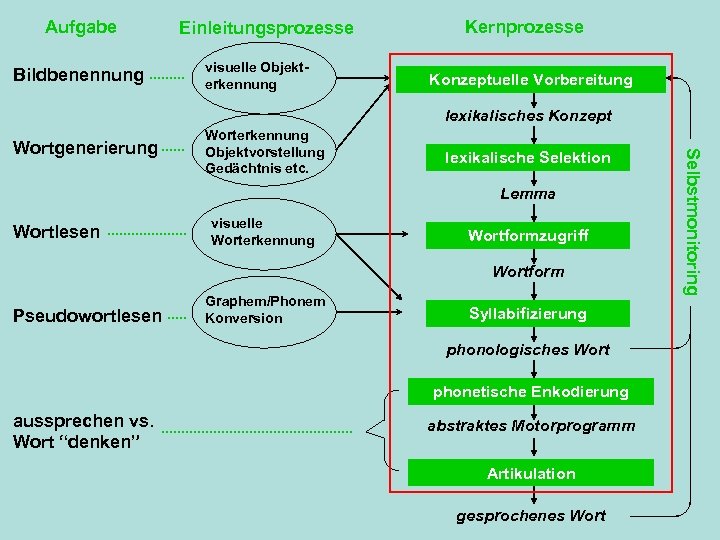

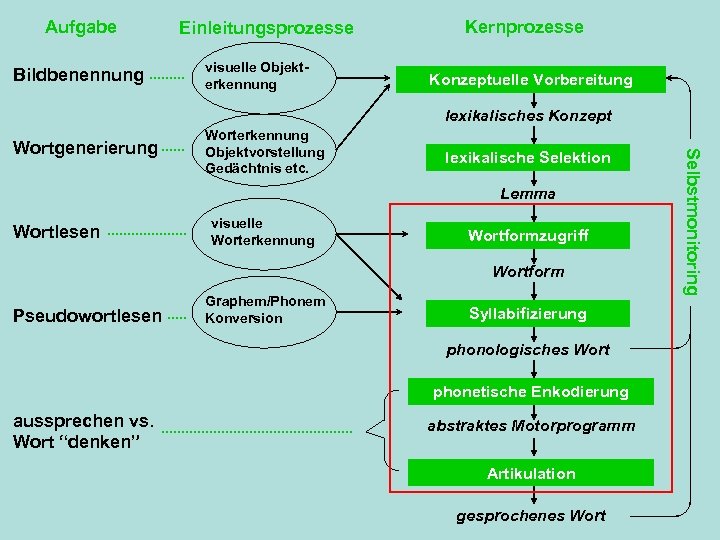

Aufgabe Bildbenennung Einleitungsprozesse visuelle Objekterkennung Kernprozesse Konzeptuelle Vorbereitung lexikalisches Konzept lexikalische Selektion Lemma Wortlesen visuelle Worterkennung Wortformzugriff Wortform Pseudowortlesen Graphem/Phonem Konversion Syllabifizierung phonologisches Wort phonetische Enkodierung aussprechen vs. Wort “denken” abstraktes Motorprogramm Artikulation gesprochenes Wort Selbstmonitoring Wortgenerierung Worterkennung Objektvorstellung Gedächtnis etc.

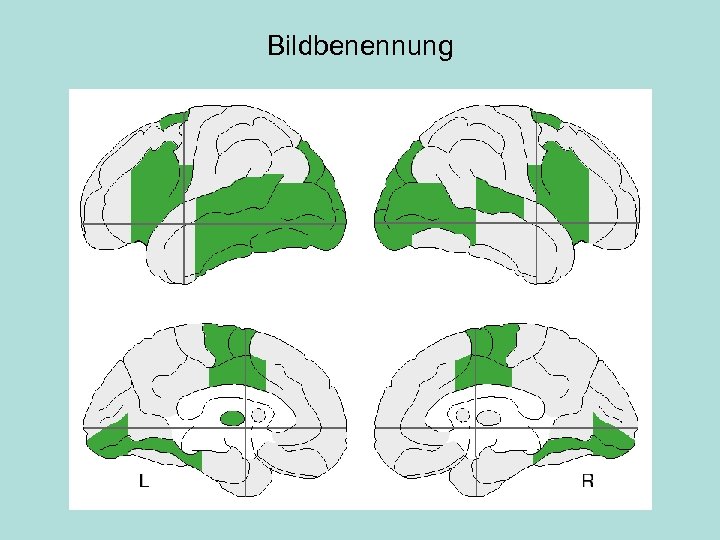

Bildbenennung

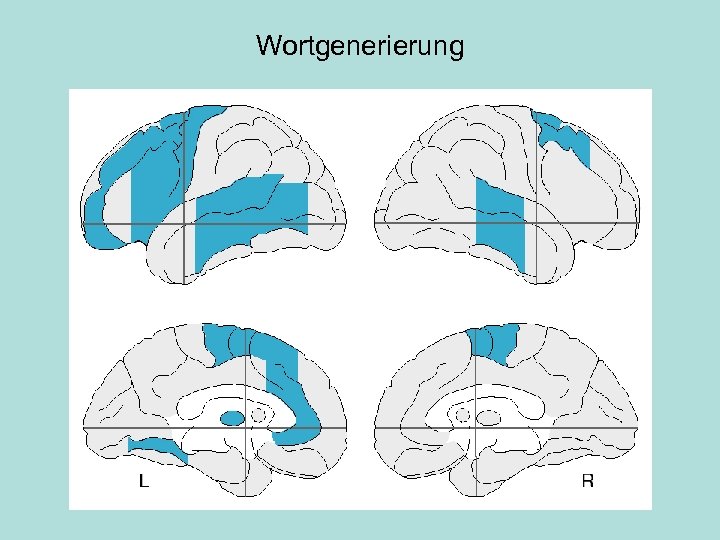

Wortgenerierung

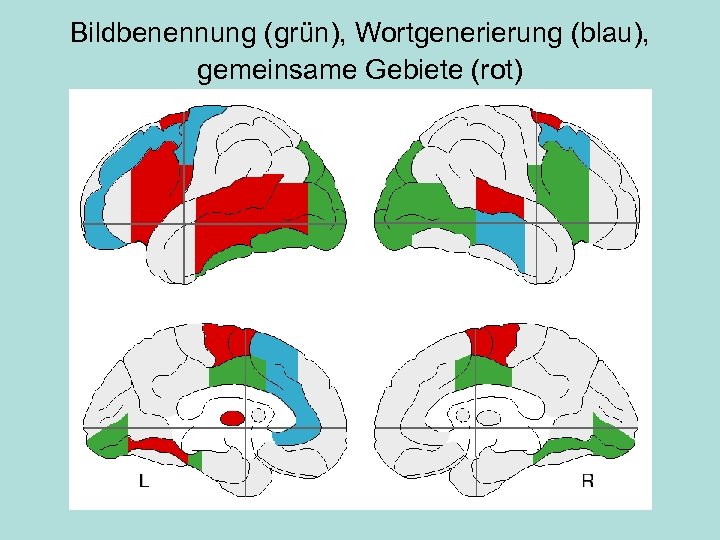

Bildbenennung (grün), Wortgenerierung (blau), gemeinsame Gebiete (rot)

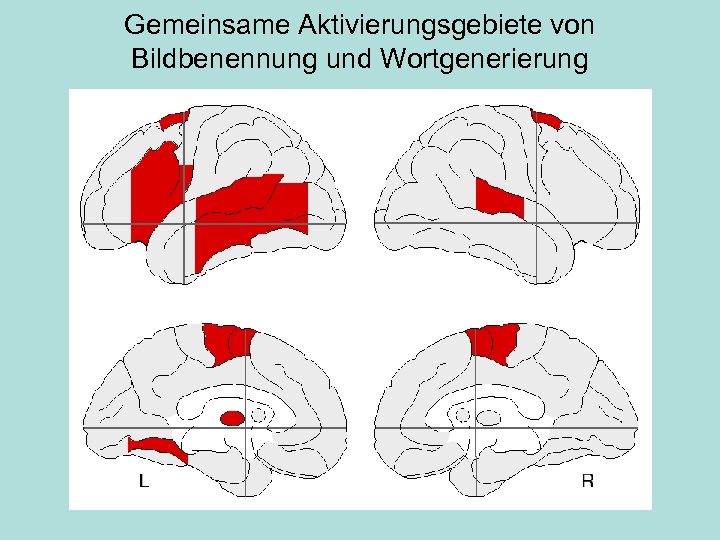

Gemeinsame Aktivierungsgebiete von Bildbenennung und Wortgenerierung

Aufgabe Bildbenennung Einleitungsprozesse visuelle Objekterkennung Kernprozesse Konzeptuelle Vorbereitung lexikalisches Konzept lexikalische Selektion Lemma Wortlesen visuelle Worterkennung Wortformzugriff Wortform Pseudowortlesen Graphem/Phonem Konversion Syllabifizierung phonologisches Wort phonetische Enkodierung aussprechen vs. Wort “denken” abstraktes Motorprogramm Artikulation gesprochenes Wort Selbstmonitoring Wortgenerierung Worterkennung Objektvorstellung Gedächtnis etc.

Aufgabe Bildbenennung Einleitungsprozesse visuelle Objekterkennung Kernprozesse Konzeptuelle Vorbereitung lexikalisches Konzept lexikalische Selektion Lemma Wortlesen visuelle Worterkennung Wortformzugriff Wortform Pseudowortlesen Graphem/Phonem Konversion Syllabifizierung phonologisches Wort phonetische Enkodierung aussprechen vs. Wort “denken” abstraktes Motorprogramm Artikulation gesprochenes Wort Selbstmonitoring Wortgenerierung Worterkennung Objektvorstellung Gedächtnis etc.

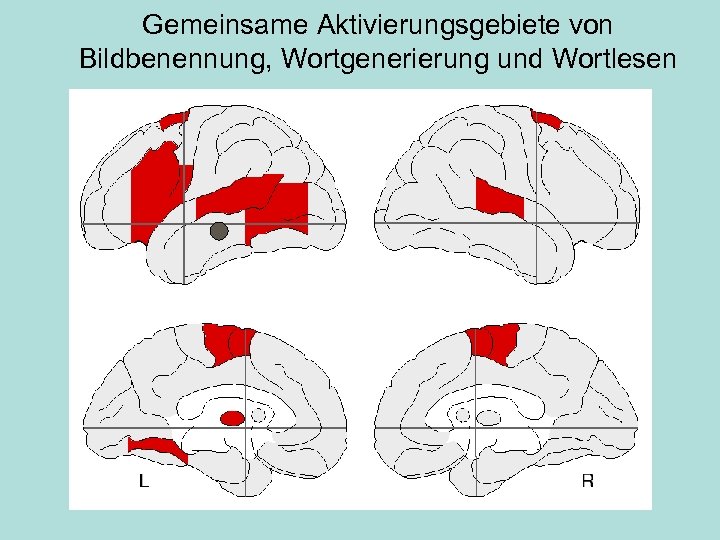

Gemeinsame Aktivierungsgebiete von Bildbenennung, Wortgenerierung und Wortlesen

Aufgabe Bildbenennung Einleitungsprozesse visuelle Objekterkennung Kernprozesse Konzeptuelle Vorbereitung lexikalisches Konzept lexikalische Selektion Lemma Wortlesen visuelle Worterkennung Wortformzugriff Wortform Pseudowortlesen Graphem/Phonem Konversion Syllabifizierung phonologisches Wort phonetische Enkodierung aussprechen vs. Wort “denken” abstraktes Motorprogramm Artikulation gesprochenes Wort Selbstmonitoring Wortgenerierung Worterkennung Objektvorstellung Gedächtnis etc.

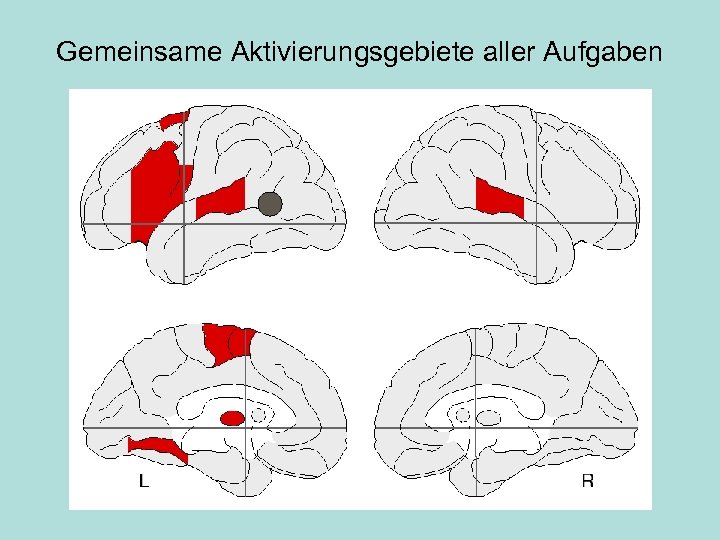

Gemeinsame Aktivierungsgebiete aller Aufgaben

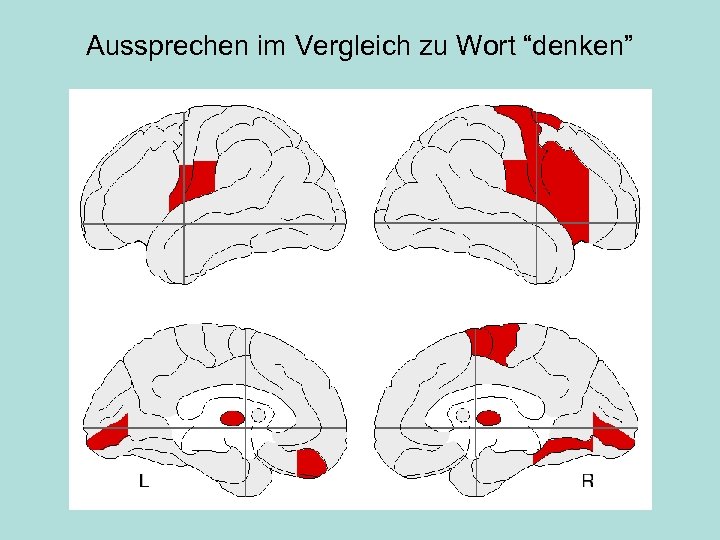

Aussprechen im Vergleich zu Wort “denken”

Schematische Darstellung des Ergebnisses der Meta-Analyse von 82 Hirnaktivierungsstudien Indefrey, P. and Levelt, W. J. M. (2004) Cognition

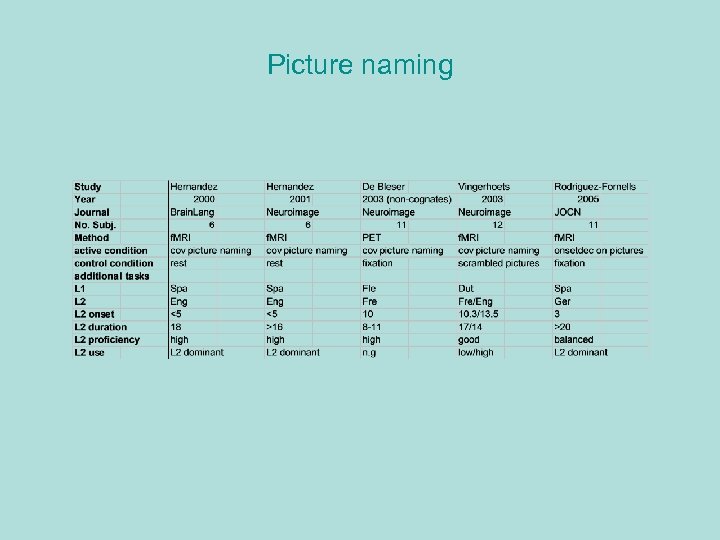

Picture naming

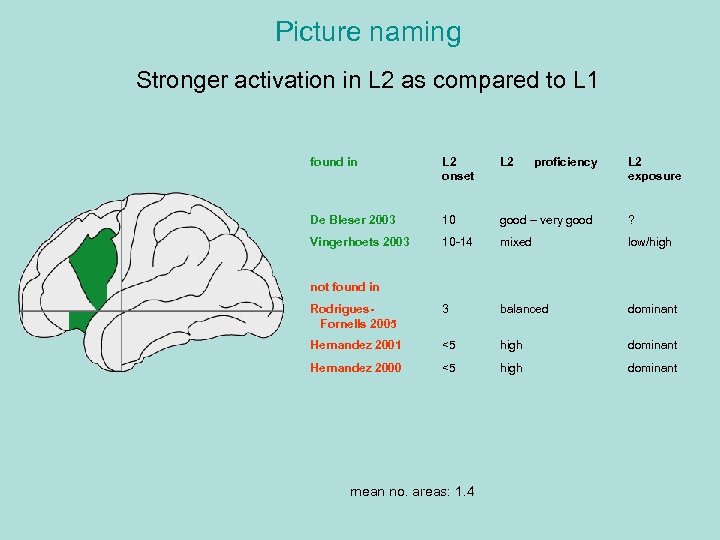

Picture naming Stronger activation in L 2 as compared to L 1 found in L 2 onset L 2 proficiency L 2 exposure De Bleser 2003 10 good – very good ? Vingerhoets 2003 10 -14 mixed low/high Rodrigues. Fornells 2005 3 balanced dominant Hernandez 2001 <5 high dominant Hernandez 2000 <5 high dominant not found in mean no. areas: 1. 4

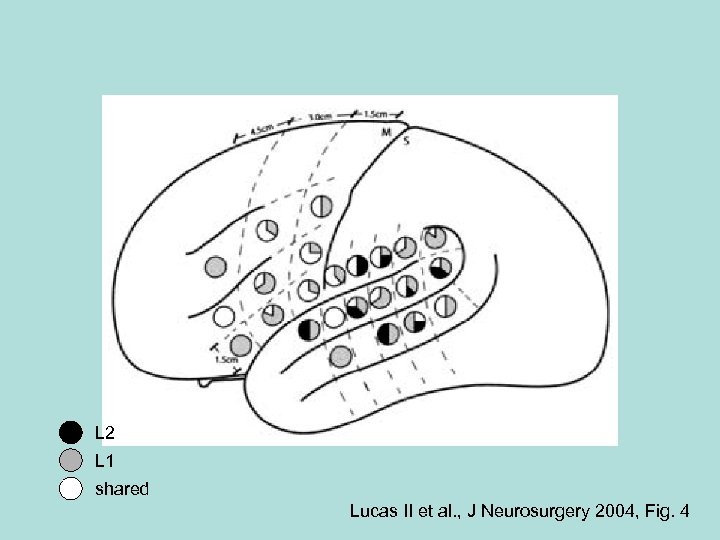

L 2 L 1 shared Lucas II et al. , J Neurosurgery 2004, Fig. 4

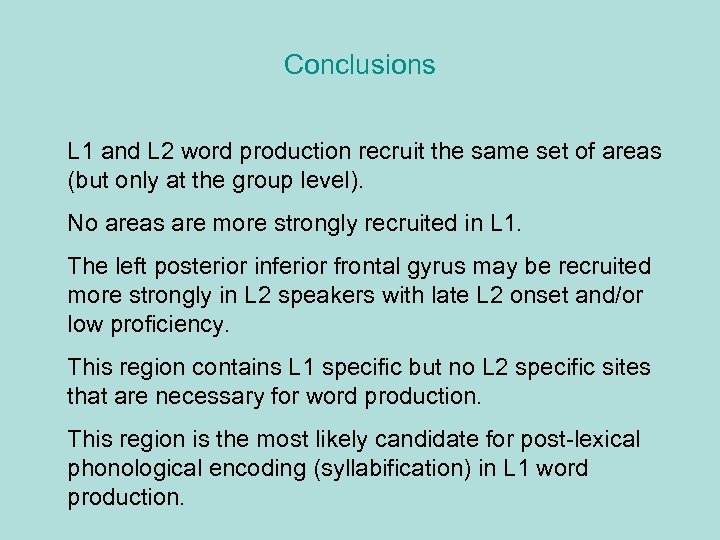

Conclusions L 1 and L 2 word production recruit the same set of areas (but only at the group level). No areas are more strongly recruited in L 1. The left posterior inferior frontal gyrus may be recruited more strongly in L 2 speakers with late L 2 onset and/or low proficiency. This region contains L 1 specific but no L 2 specific sites that are necessary for word production. This region is the most likely candidate for post-lexical phonological encoding (syllabification) in L 1 word production.

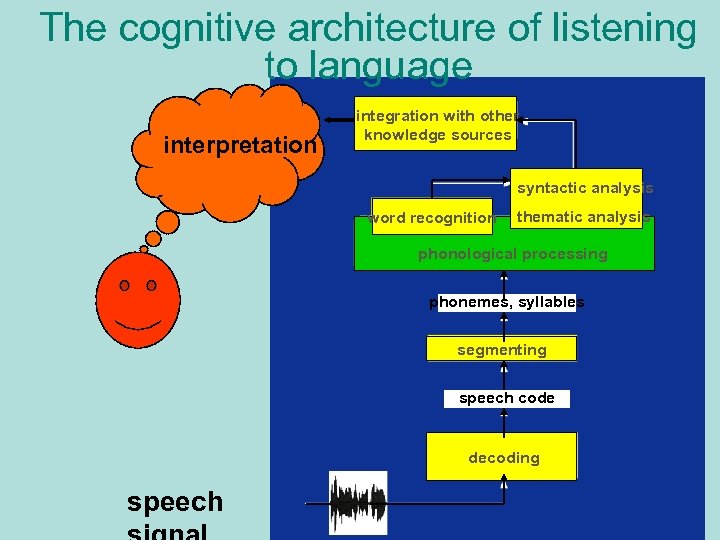

The cognitive architecture of listening to language interpretation integration with other knowledge sources syntactic analysis word recognition thematic analysis phonological processing phonemes, syllables segmenting speech code decoding speech

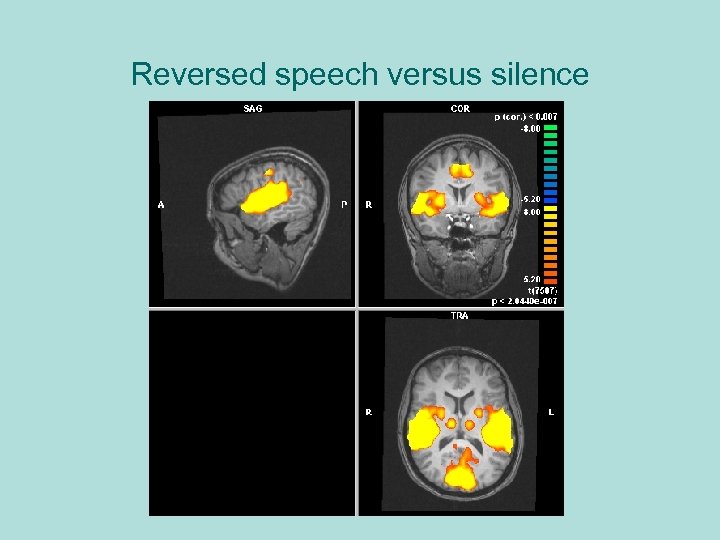

Reversed speech versus silence

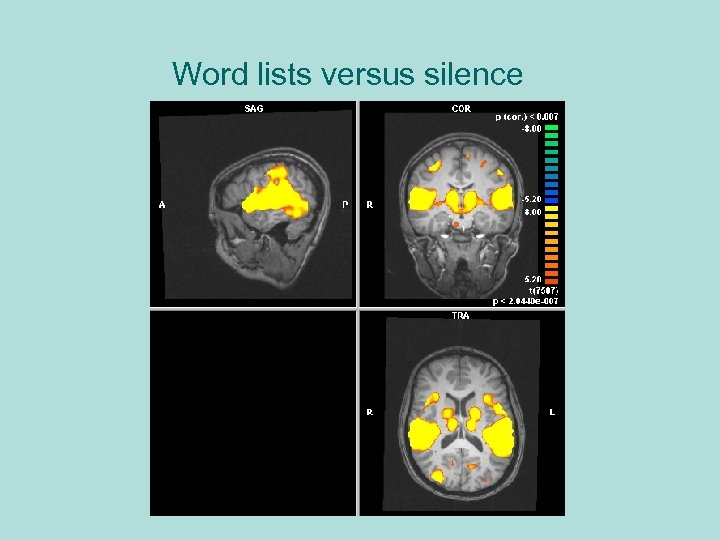

Word lists versus silence

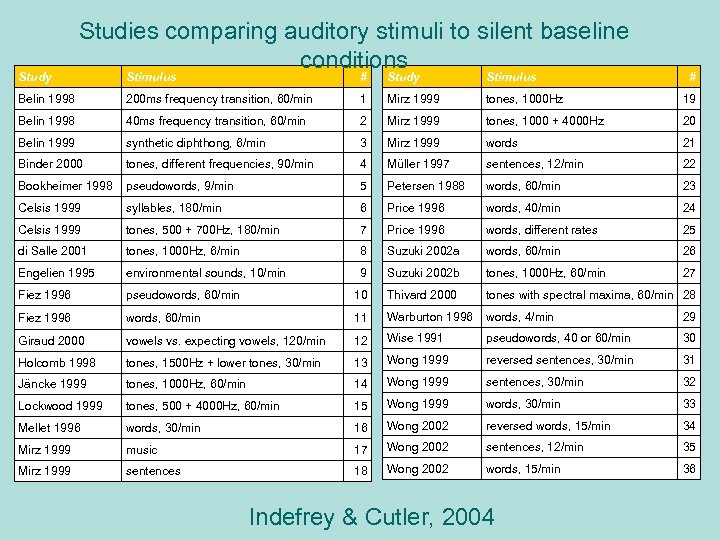

Studies comparing auditory stimuli to silent baseline conditions Stimulus # Study Stimulus Belin 1998 200 ms frequency transition, 60/min 1 Mirz 1999 tones, 1000 Hz 19 Belin 1998 40 ms frequency transition, 60/min 2 Mirz 1999 tones, 1000 + 4000 Hz 20 Belin 1999 synthetic diphthong, 6/min 3 Mirz 1999 words 21 Binder 2000 tones, different frequencies, 90/min 4 Müller 1997 sentences, 12/min 22 Bookheimer 1998 pseudowords, 9/min 5 Petersen 1988 words, 60/min 23 Celsis 1999 syllables, 180/min 6 Price 1996 words, 40/min 24 Celsis 1999 tones, 500 + 700 Hz, 180/min 7 Price 1996 words, different rates 25 di Salle 2001 tones, 1000 Hz, 6/min 8 Suzuki 2002 a words, 60/min 26 Engelien 1995 environmental sounds, 10/min 9 Suzuki 2002 b tones, 1000 Hz, 60/min 27 Fiez 1996 pseudowords, 60/min 10 Thivard 2000 tones with spectral maxima, 60/min 28 Fiez 1996 words, 60/min 11 Warburton 1996 words, 4/min 29 Giraud 2000 vowels vs. expecting vowels, 120/min 12 Wise 1991 pseudowords, 40 or 60/min 30 Holcomb 1998 tones, 1500 Hz + lower tones, 30/min 13 Wong 1999 reversed sentences, 30/min 31 Jäncke 1999 tones, 1000 Hz, 60/min 14 Wong 1999 sentences, 30/min 32 Lockwood 1999 tones, 500 + 4000 Hz, 60/min 15 Wong 1999 words, 30/min 33 Mellet 1996 words, 30/min 16 Wong 2002 reversed words, 15/min 34 Mirz 1999 music 17 Wong 2002 sentences, 12/min 35 Mirz 1999 sentences 18 Wong 2002 words, 15/min 36 Study Indefrey & Cutler, 2004 #

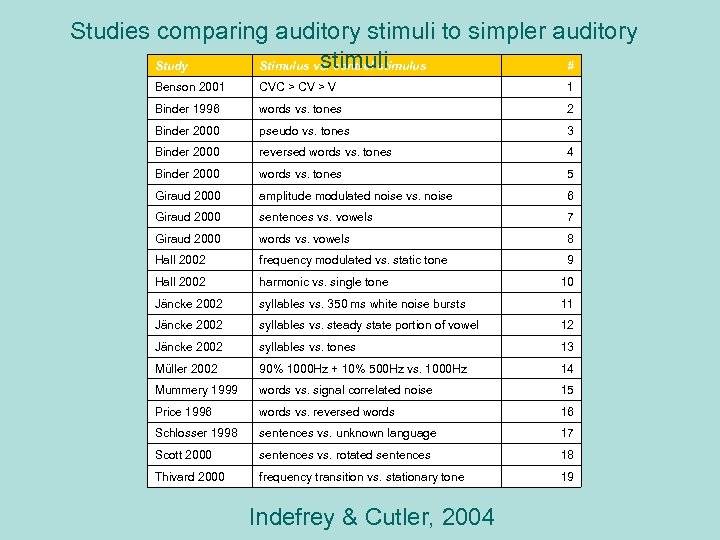

Studies comparing auditory stimuli to simpler auditory stimuli Study Stimulus vs. control stimulus # Benson 2001 CVC > CV > V 1 Binder 1996 words vs. tones 2 Binder 2000 pseudo vs. tones 3 Binder 2000 reversed words vs. tones 4 Binder 2000 words vs. tones 5 Giraud 2000 amplitude modulated noise vs. noise 6 Giraud 2000 sentences vs. vowels 7 Giraud 2000 words vs. vowels 8 Hall 2002 frequency modulated vs. static tone 9 Hall 2002 harmonic vs. single tone 10 Jäncke 2002 syllables vs. 350 ms white noise bursts 11 Jäncke 2002 syllables vs. steady state portion of vowel 12 Jäncke 2002 syllables vs. tones 13 Müller 2002 90% 1000 Hz + 10% 500 Hz vs. 1000 Hz 14 Mummery 1999 words vs. signal correlated noise 15 Price 1996 words vs. reversed words 16 Schlosser 1998 sentences vs. unknown language 17 Scott 2000 sentences vs. rotated sentences 18 Thivard 2000 frequency transition vs. stationary tone 19 Indefrey & Cutler, 2004

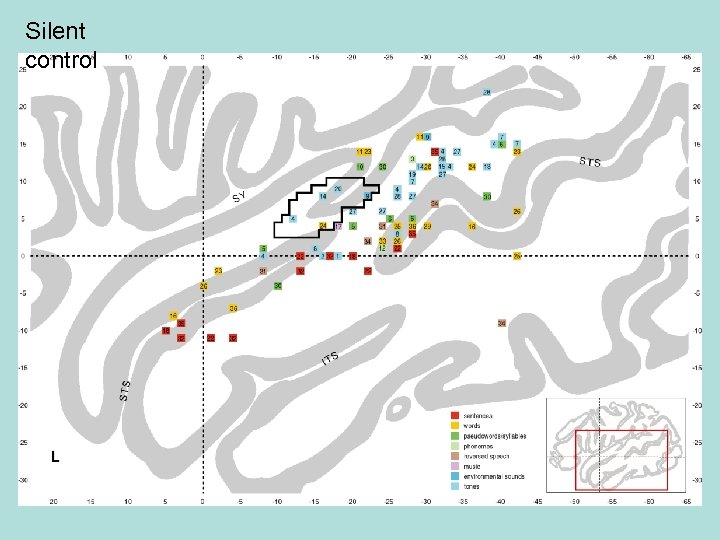

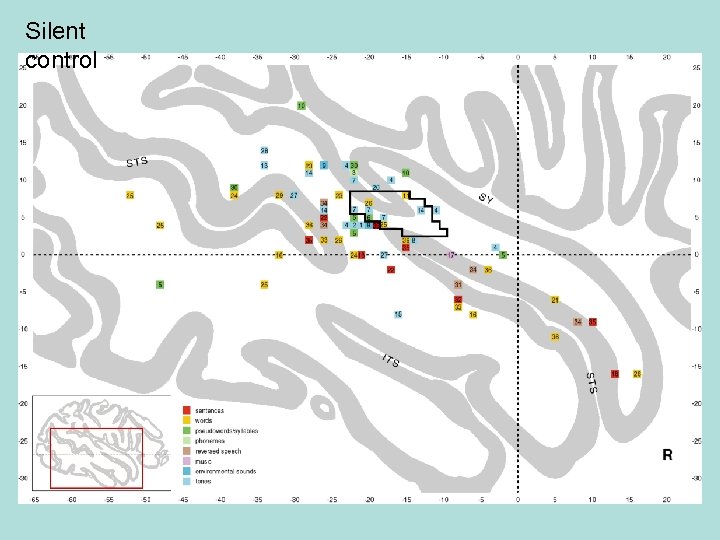

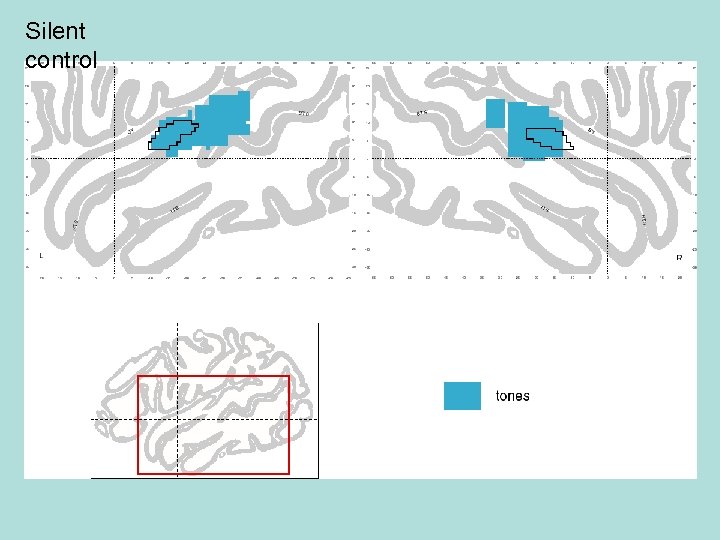

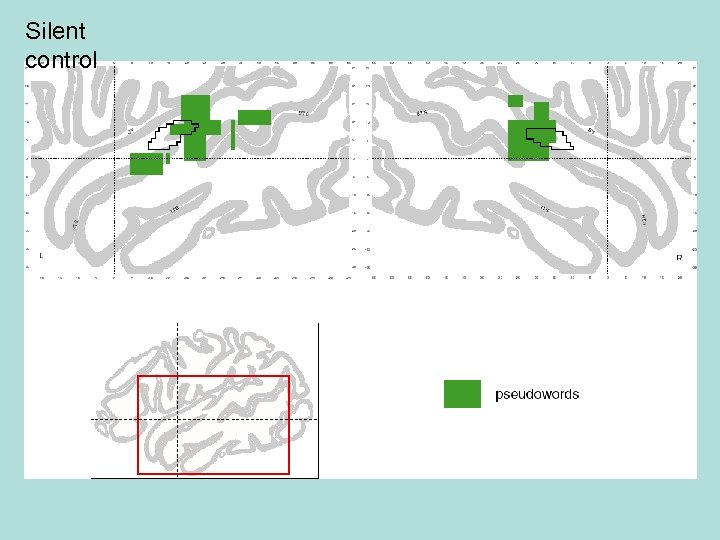

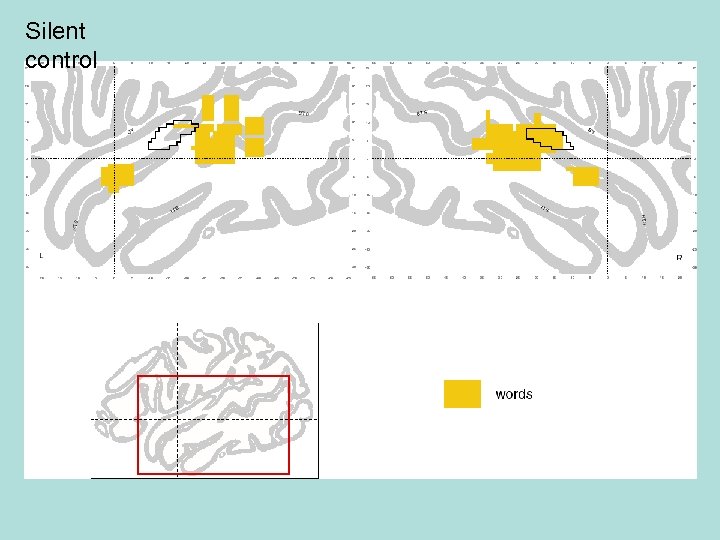

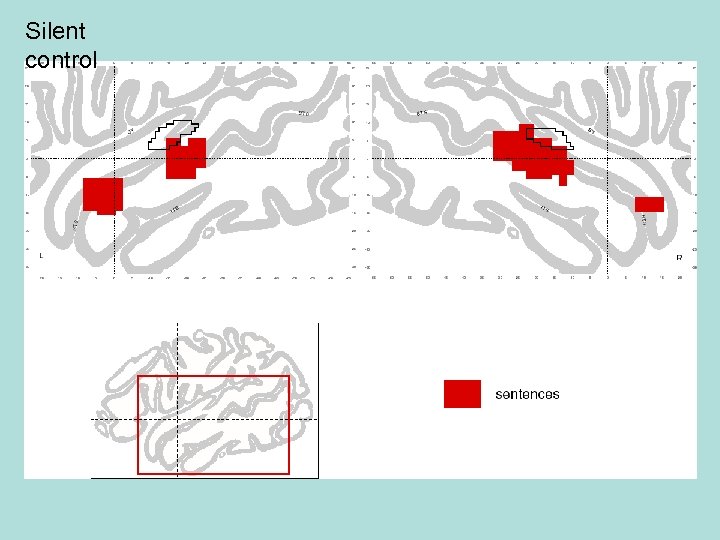

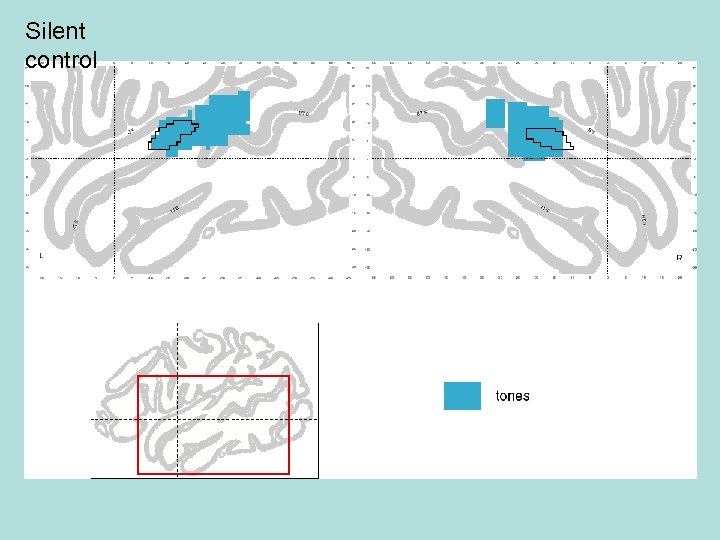

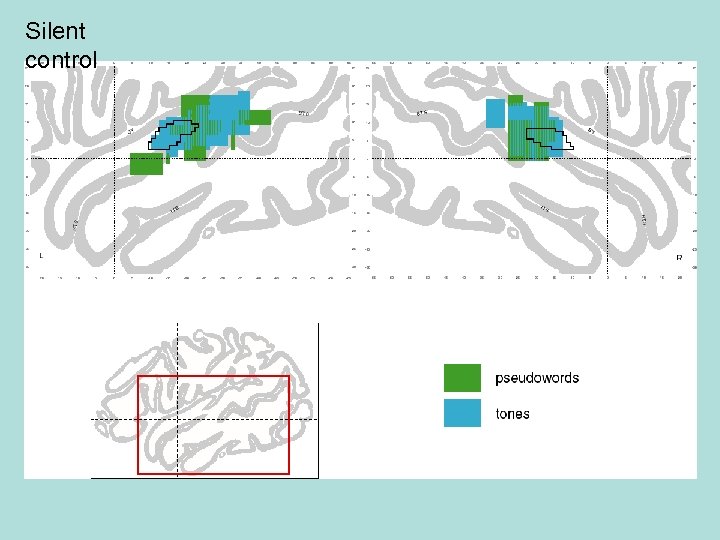

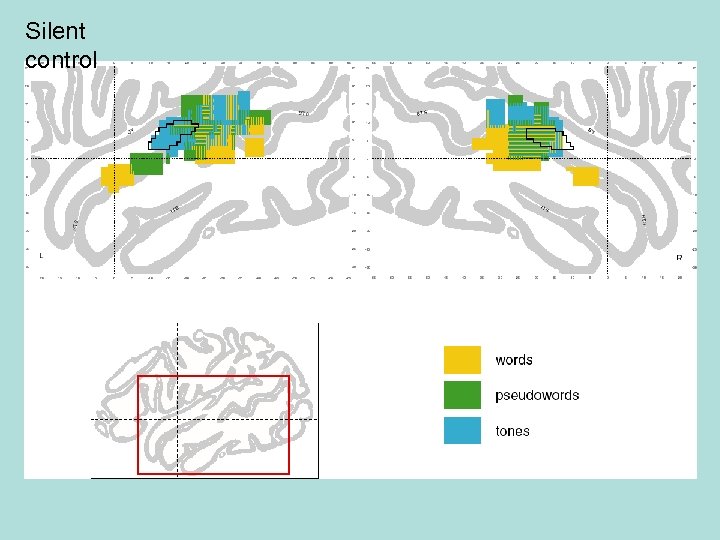

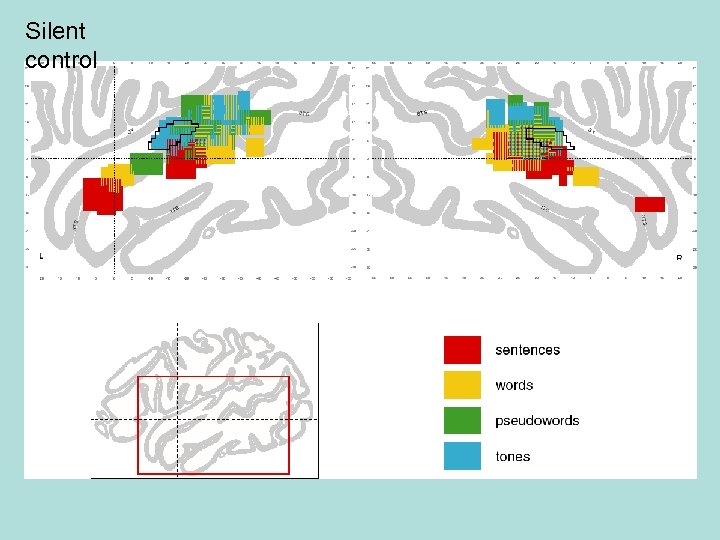

Silent control

Silent control

Silent control

Silent control

Silent control

Silent control

Silent control

Silent control

Silent control

Silent control

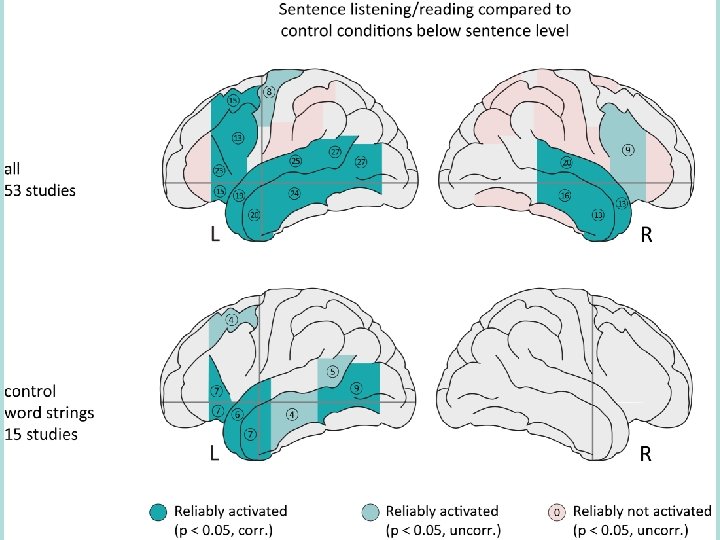

Summary Listening to speech without an additional task induces extensive bilateral temporal activation but no reliable activation of Broca’s area.

Summary With increasing linguistic complexity of stimuli, the distance of activation maxima from the primary auditory cortex increases; particularly in the left hemisphere. It seems to be the highest linguistic processing level that leads to the most significant activation difference compared to a silent control.

Summary The left hemisphere shows a clearer stimulus-specific differentiation of activation maxima. Areas that seem to be especially related to (post-) lexical and sentence level processing can be identified.

Summary bilateral posterior STG: phonology left posterior STS: lexical phonology left anterior STS: possibly lexical and sentential prosody, possibly lexical and sentential meaning

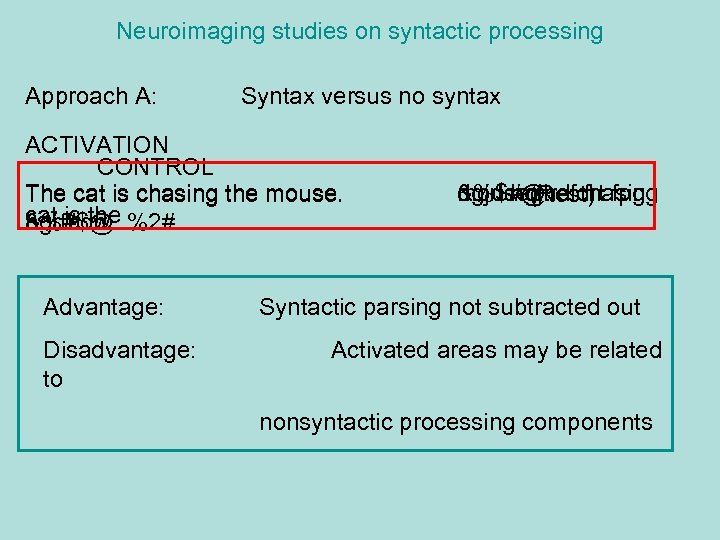

Neuroimaging studies on syntactic processing Approach A: Syntax versus no syntax ACTIVATION CONTROL The cat is chasing the mouse. cat is the %2# hgrfbdw &%#$@ Advantage: Disadvantage: to dgjrt hgjtrdf frt fpg &%$#@ chasing mouse(Rest) the Syntactic parsing not subtracted out Activated areas may be related nonsyntactic processing components

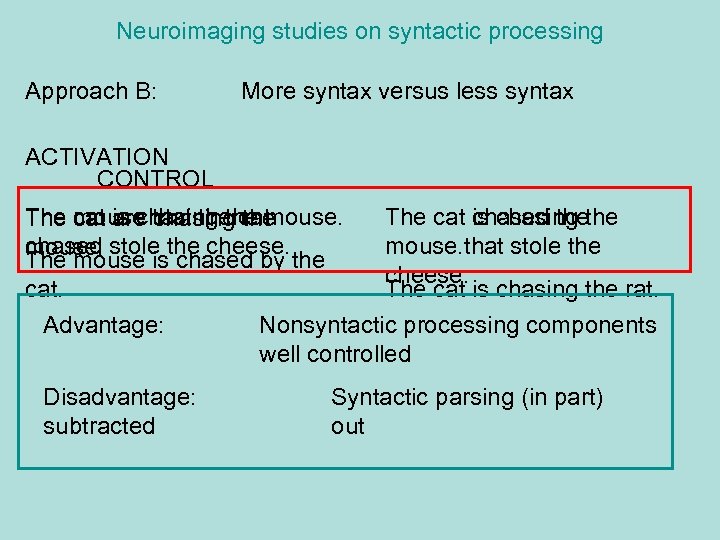

Neuroimaging studies on syntactic processing Approach B: More syntax versus less syntax ACTIVATION CONTROL The cat is chasing the mouse that the cat chased the are chasing the mouse. that stole the chased mouse. stole the cheese. The mouse is chased by the cheese. The cat is chasing the rat. cat. Advantage: Nonsyntactic processing components well controlled Disadvantage: subtracted Syntactic parsing (in part) out

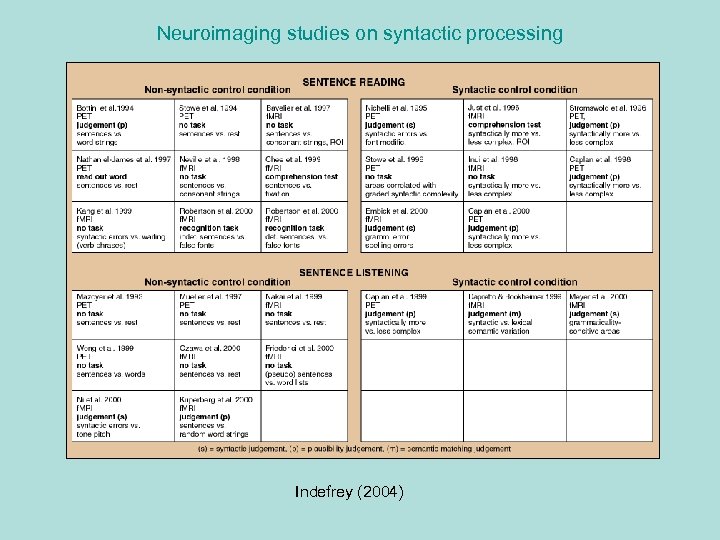

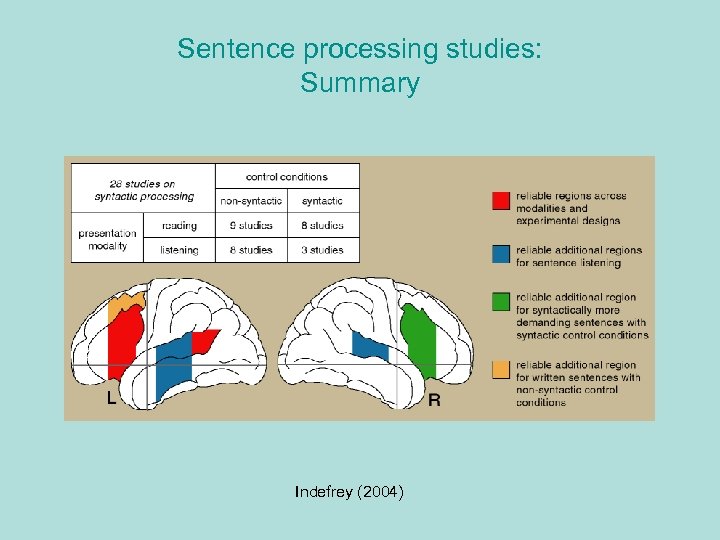

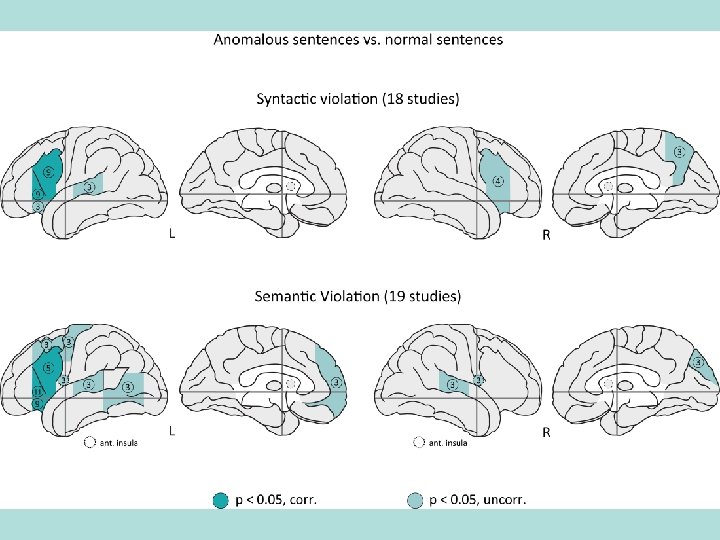

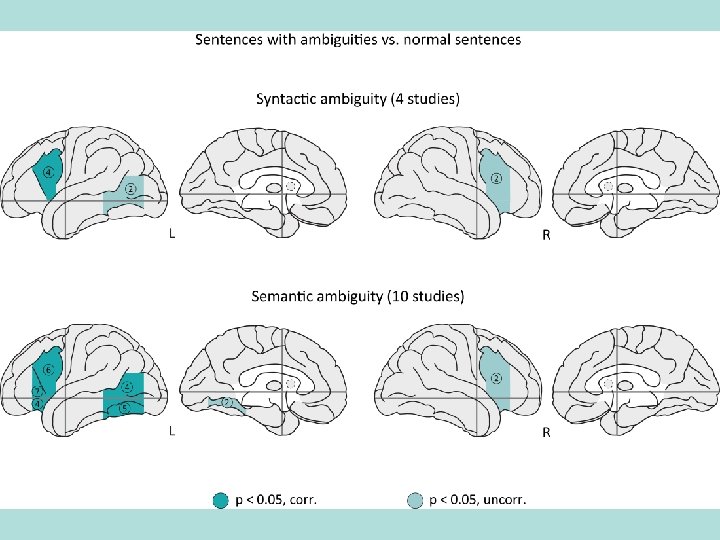

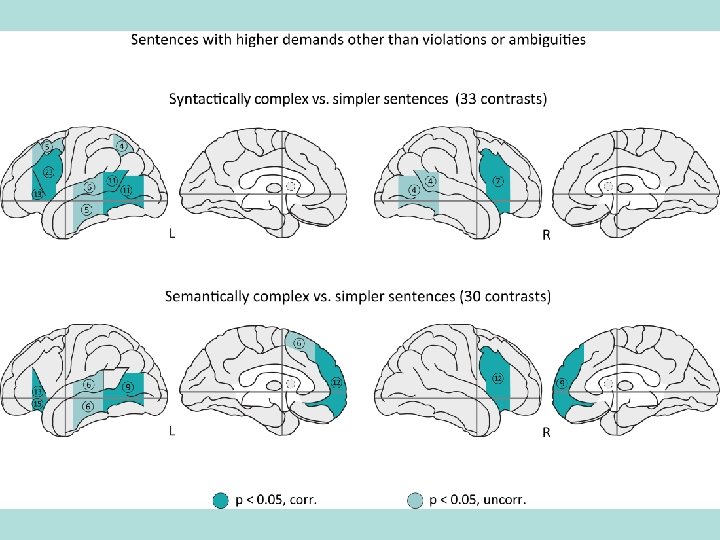

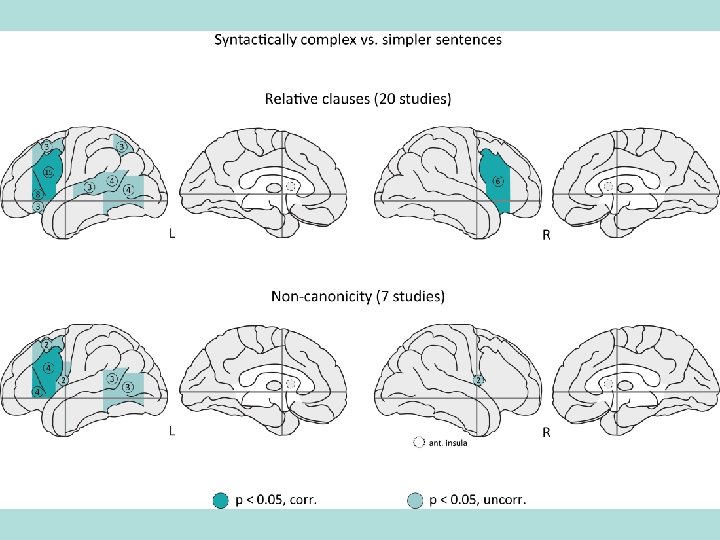

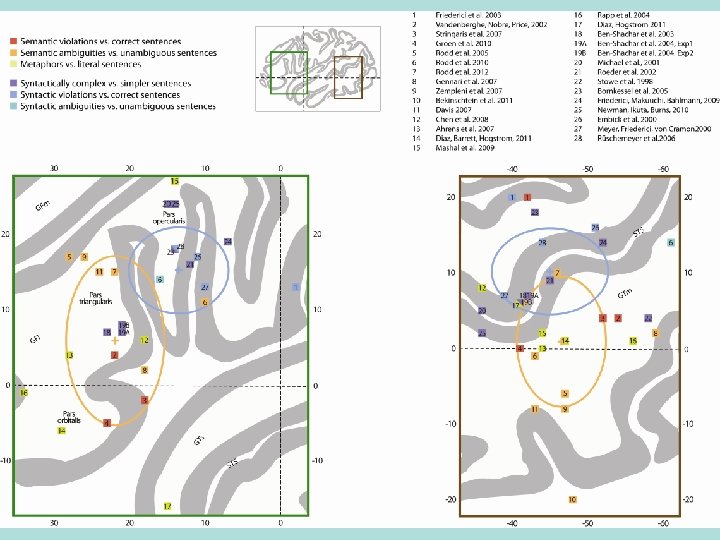

Neuroimaging studies on syntactic processing Indefrey (2004)

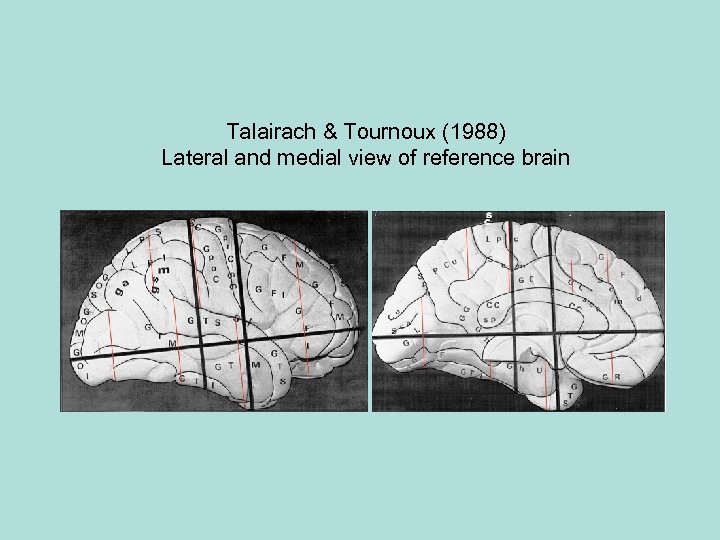

Talairach & Tournoux (1988) Lateral and medial view of reference brain

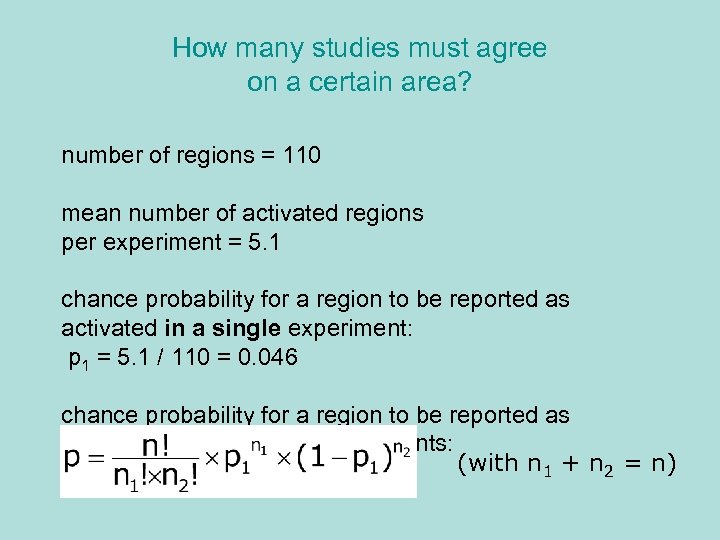

How many studies must agree on a certain area? number of regions = 110 mean number of activated regions per experiment = 5. 1 chance probability for a region to be reported as activated in a single experiment: p 1 = 5. 1 / 110 = 0. 046 chance probability for a region to be reported as activated in n 1 out of n experiments: (with n 1 + n 2 = n)

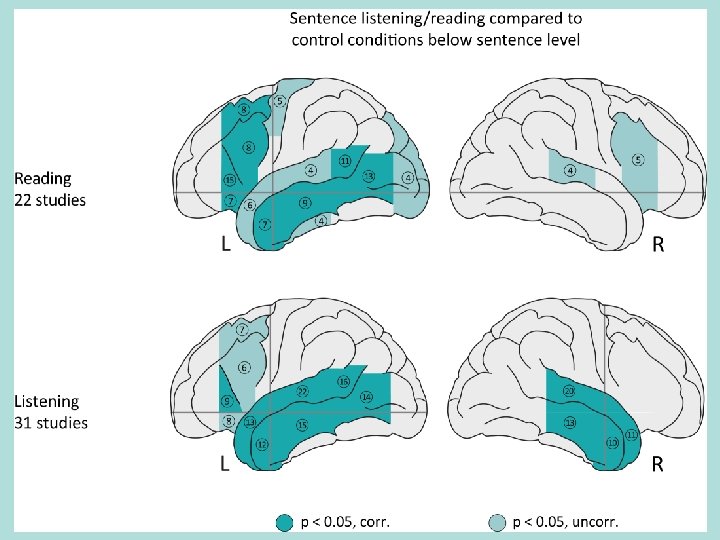

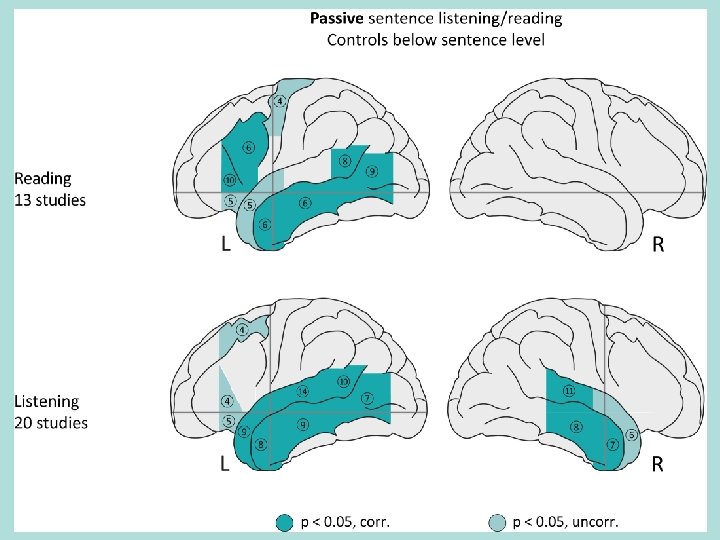

Sentence processing studies: Summary Indefrey (2004)

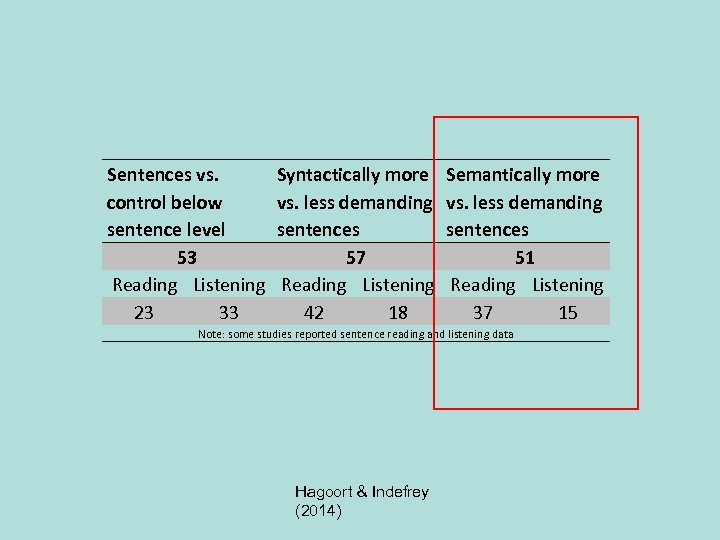

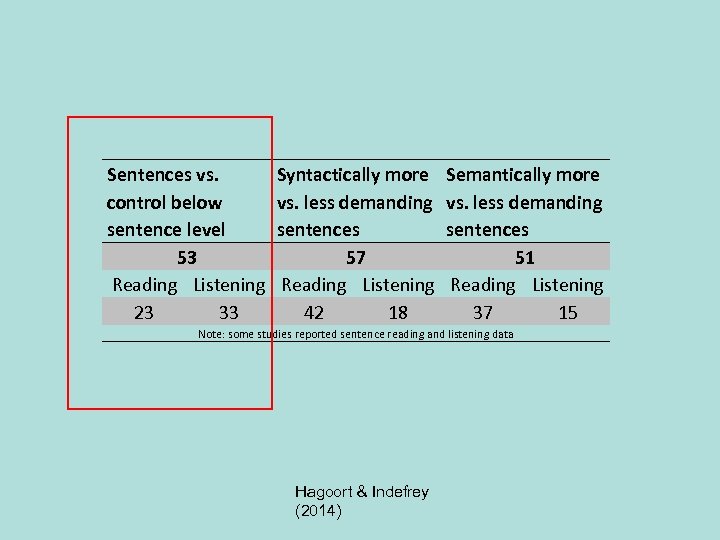

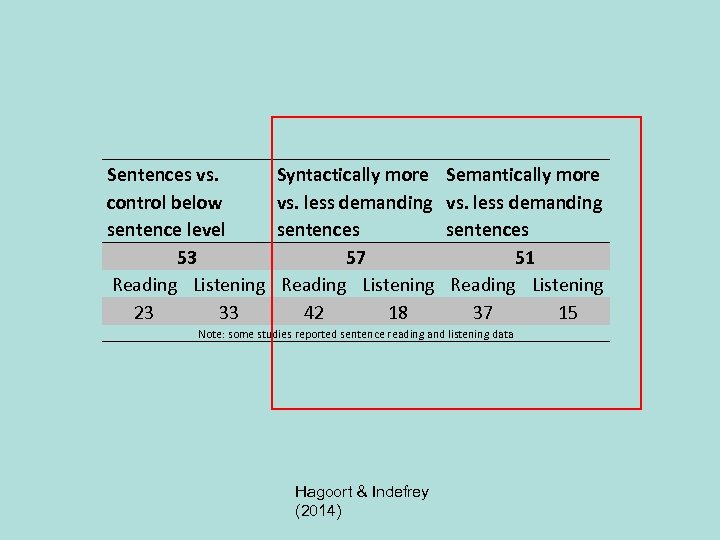

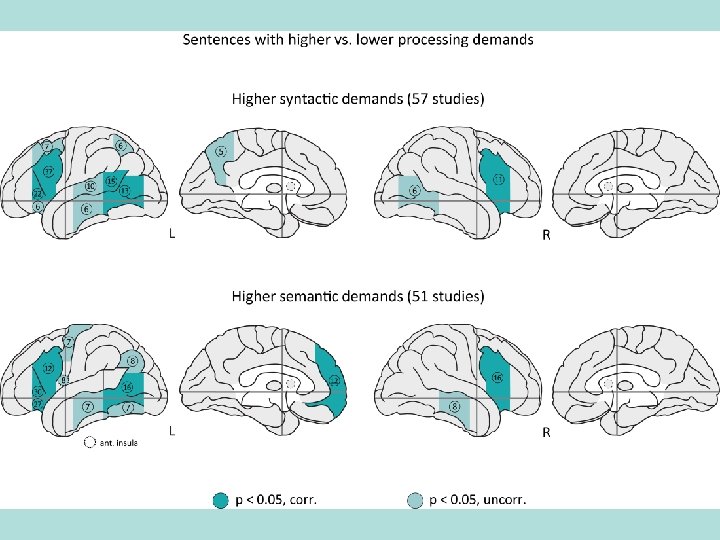

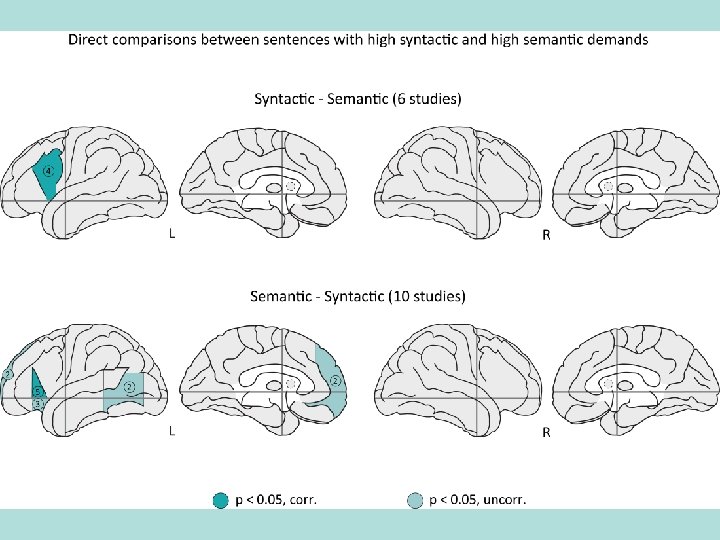

Sentences vs. control below sentence level 53 Reading Listening 23 33 Syntactically more vs. less demanding sentences 57 Reading Listening 42 18 Semantically more vs. less demanding sentences 51 Reading Listening 37 15 Note: some studies reported sentence reading and listening data Hagoort & Indefrey (2014)

Sentences vs. control below sentence level 53 Reading Listening 23 33 Syntactically more vs. less demanding sentences 57 Reading Listening 42 18 Semantically more vs. less demanding sentences 51 Reading Listening 37 15 Note: some studies reported sentence reading and listening data Hagoort & Indefrey (2014)

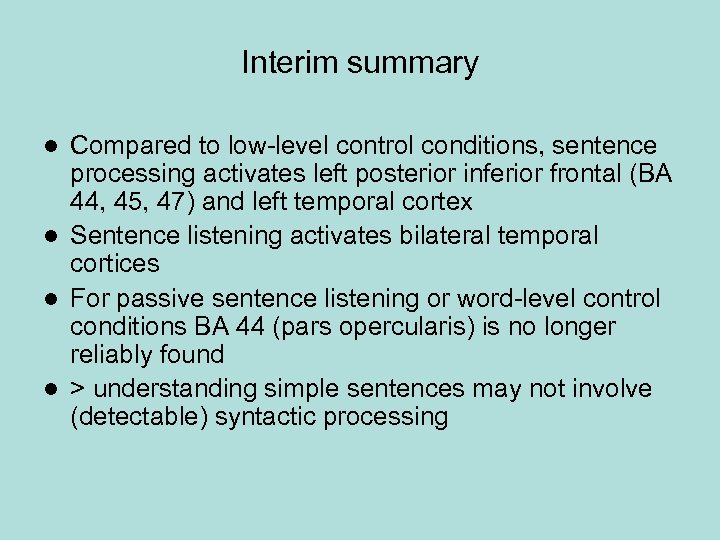

Interim summary Compared to low-level control conditions, sentence processing activates left posterior inferior frontal (BA 44, 45, 47) and left temporal cortex l Sentence listening activates bilateral temporal cortices l For passive sentence listening or word-level control conditions BA 44 (pars opercularis) is no longer reliably found l > understanding simple sentences may not involve (detectable) syntactic processing l

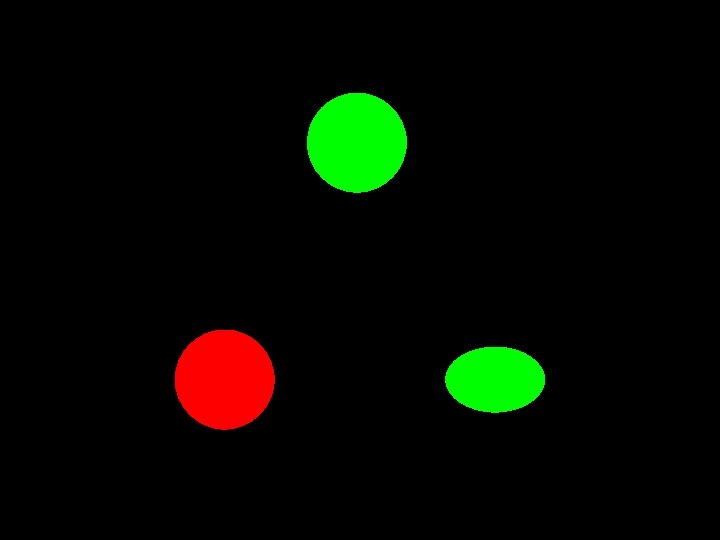

wegstossen-Animation(1)

wegstossen-Animation(2)

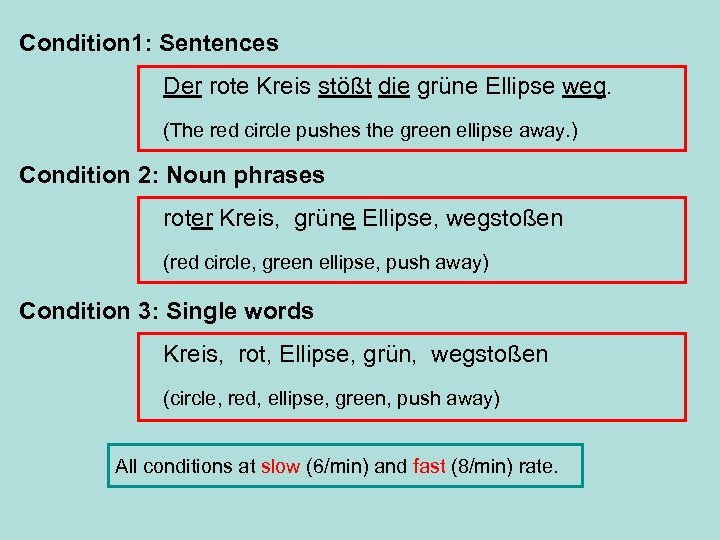

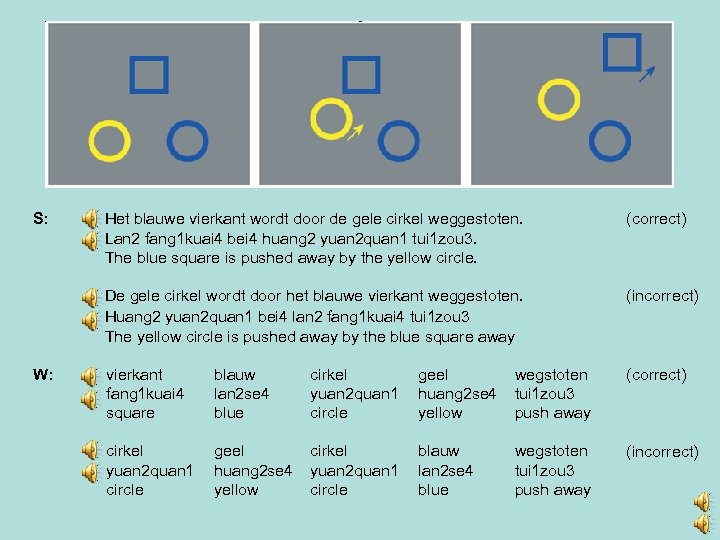

Condition 1: Sentences Der rote Kreis stößt die grüne Ellipse weg. (The red circle pushes the green ellipse away. ) Condition 2: Noun phrases roter Kreis, grüne Ellipse, wegstoßen (red circle, green ellipse, push away) Condition 3: Single words Kreis, rot, Ellipse, grün, wegstoßen (circle, red, ellipse, green, push away) All conditions at slow (6/min) and fast (8/min) rate.

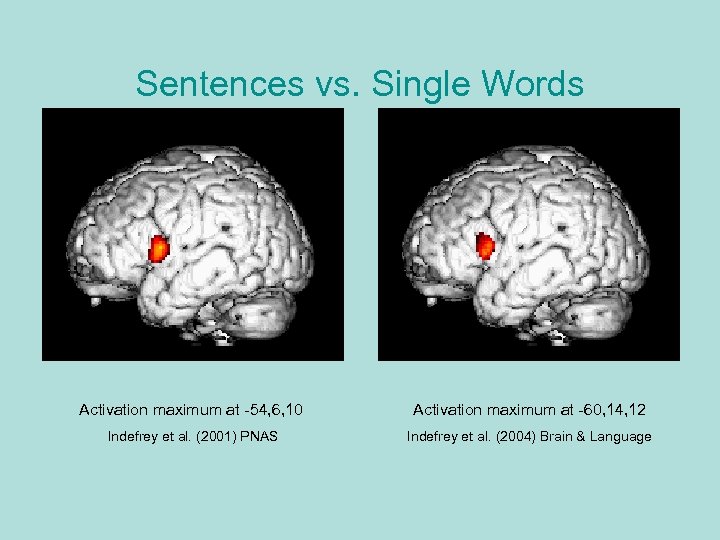

Sentences vs. Single Words Activation maximum at -54, 6, 10 Activation maximum at -60, 14, 12 Indefrey et al. (2001) PNAS Indefrey et al. (2004) Brain & Language

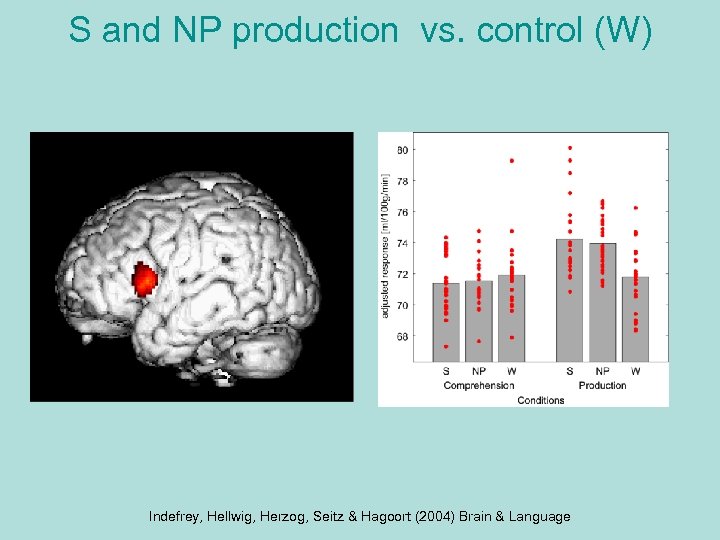

S and NP production vs. control (W) Indefrey, Hellwig, Herzog, Seitz & Hagoort (2004) Brain & Language

Sentences vs. control below sentence level 53 Reading Listening 23 33 Syntactically more vs. less demanding sentences 57 Reading Listening 42 18 Semantically more vs. less demanding sentences 51 Reading Listening 37 15 Note: some studies reported sentence reading and listening data Hagoort & Indefrey (2014)

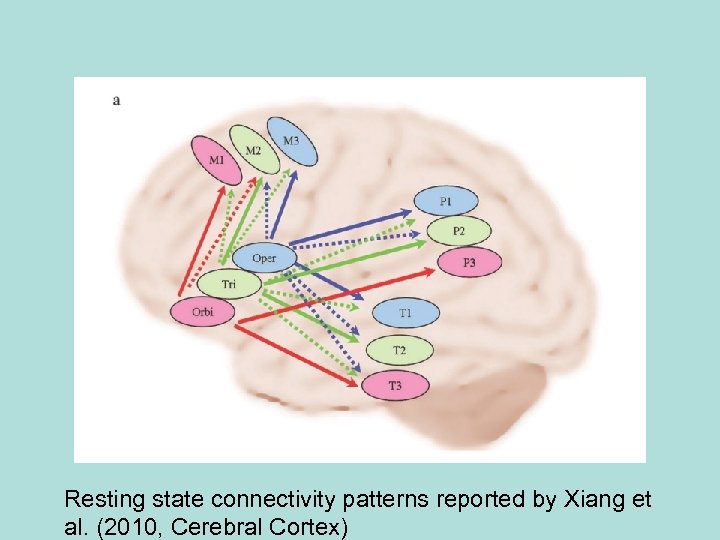

Resting state connectivity patterns reported by Xiang et al. (2010, Cerebral Cortex)

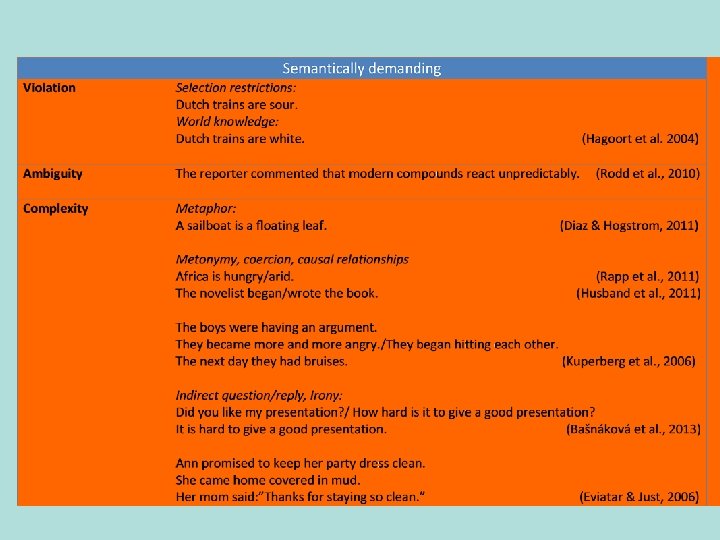

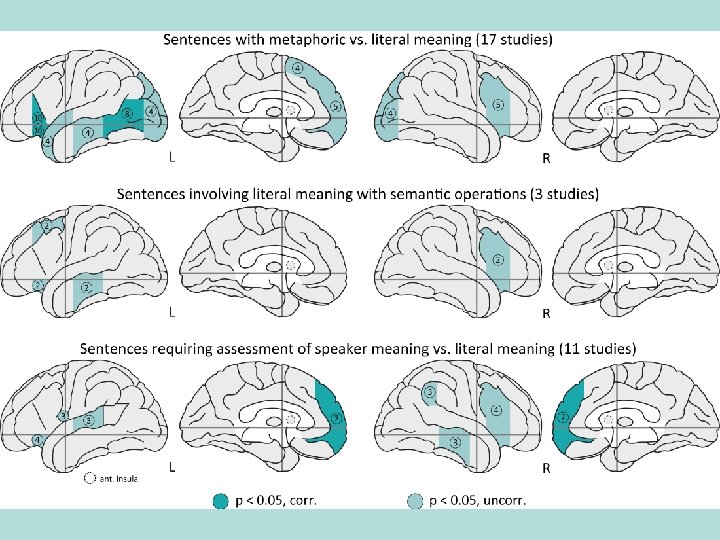

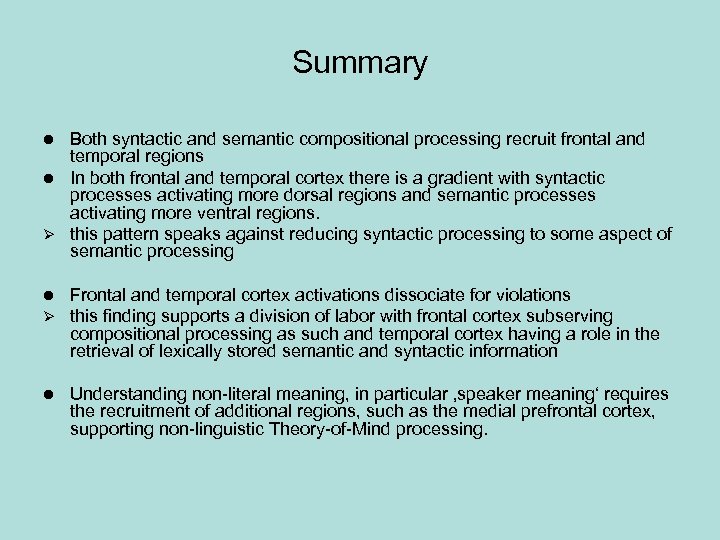

Summary Both syntactic and semantic compositional processing recruit frontal and temporal regions l In both frontal and temporal cortex there is a gradient with syntactic processes activating more dorsal regions and semantic processes activating more ventral regions. Ø this pattern speaks against reducing syntactic processing to some aspect of semantic processing l l Ø Frontal and temporal cortex activations dissociate for violations this finding supports a division of labor with frontal cortex subserving compositional processing as such and temporal cortex having a role in the retrieval of lexically stored semantic and syntactic information l Understanding non-literal meaning, in particular ‚speaker meaning‘ requires the recruitment of additional regions, such as the medial prefrontal cortex, supporting non-linguistic Theory-of-Mind processing.

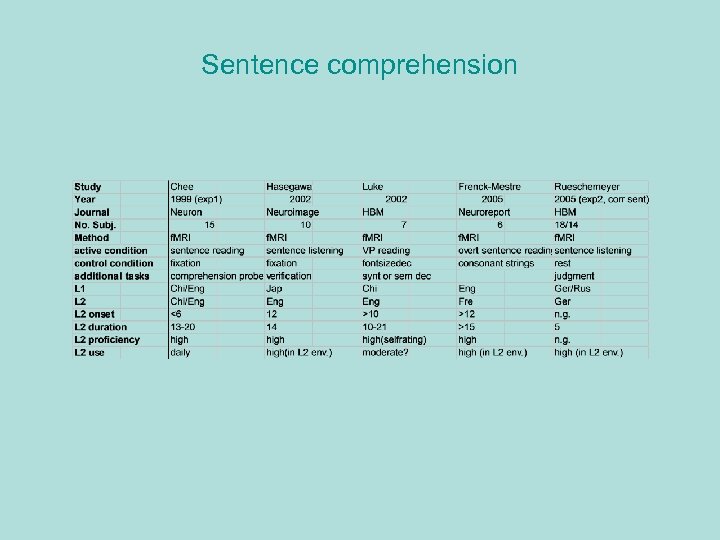

Sentence comprehension

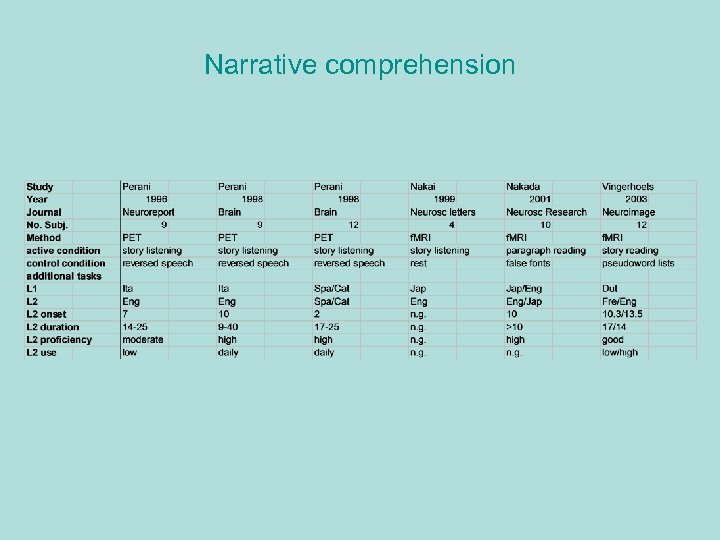

Narrative comprehension

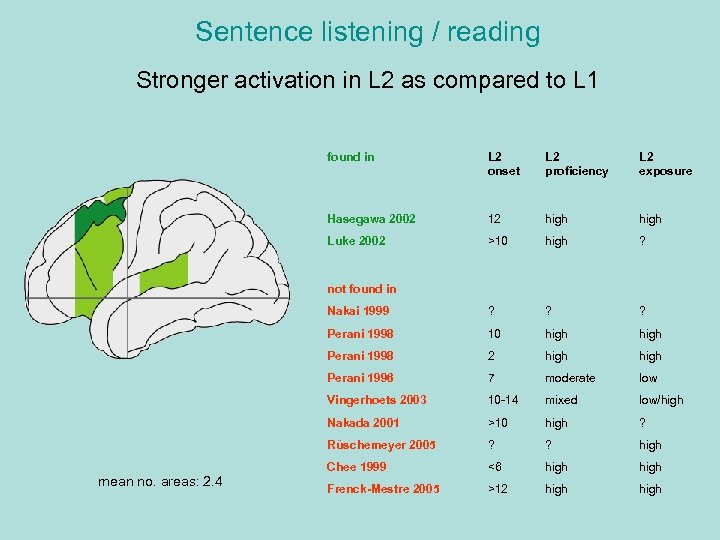

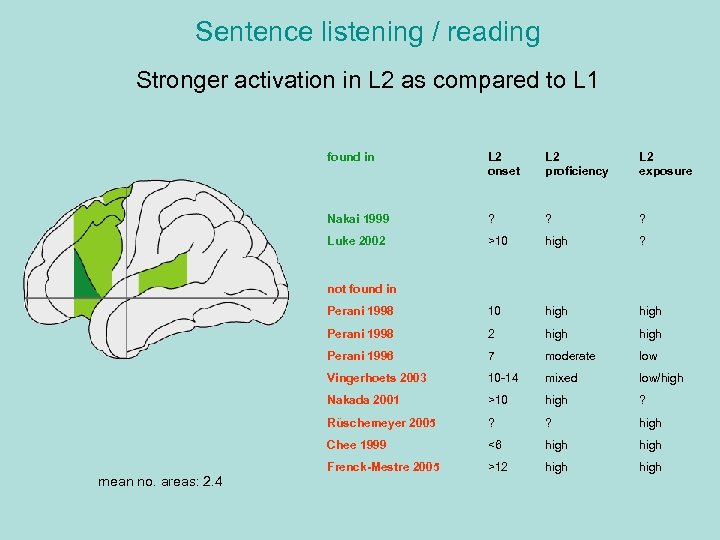

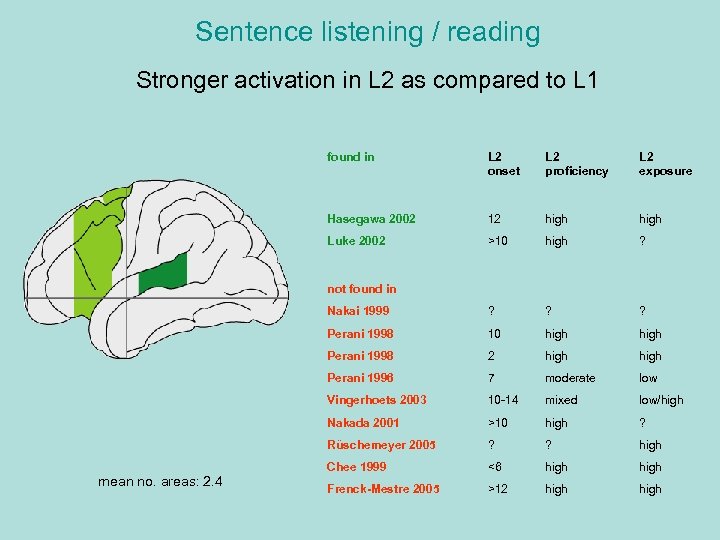

Sentence listening / reading Stronger activation in L 2 as compared to L 1 found in L 2 onset L 2 proficiency L 2 exposure Hasegawa 2002 12 high Luke 2002 >10 high ? Nakai 1999 ? ? ? Perani 1998 10 high Perani 1998 2 high Perani 1996 7 moderate low Vingerhoets 2003 10 -14 mixed low/high Nakada 2001 >10 high ? Rüschemeyer 2005 ? ? high Chee 1999 <6 high Frenck-Mestre 2005 >12 high not found in mean no. areas: 2. 4

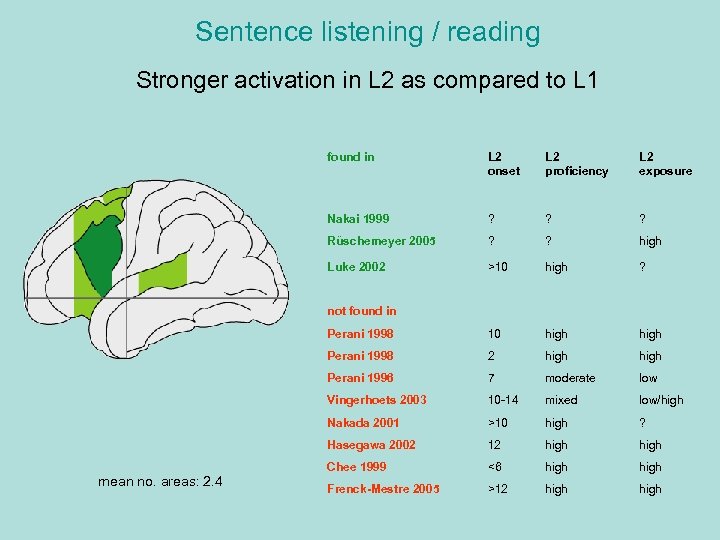

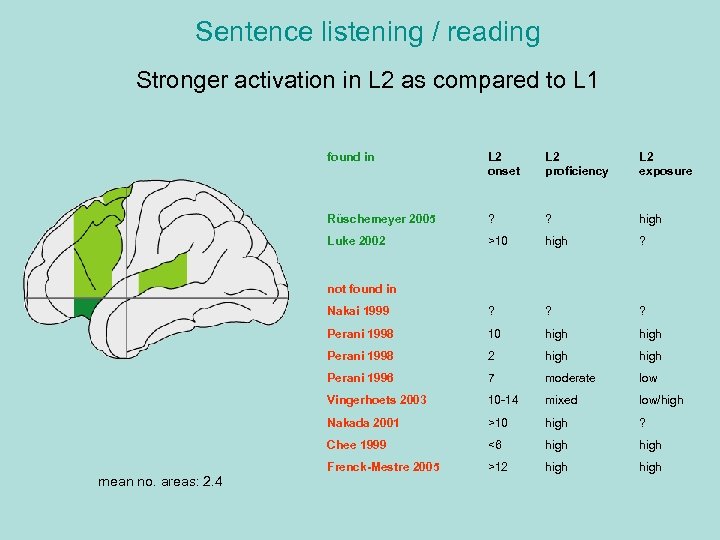

Sentence listening / reading Stronger activation in L 2 as compared to L 1 found in L 2 onset L 2 proficiency L 2 exposure Nakai 1999 ? ? ? Rüschemeyer 2005 ? ? high Luke 2002 >10 high ? Perani 1998 10 high Perani 1998 2 high Perani 1996 7 moderate low Vingerhoets 2003 10 -14 mixed low/high Nakada 2001 >10 high ? Hasegawa 2002 12 high Chee 1999 <6 high Frenck-Mestre 2005 >12 high not found in mean no. areas: 2. 4

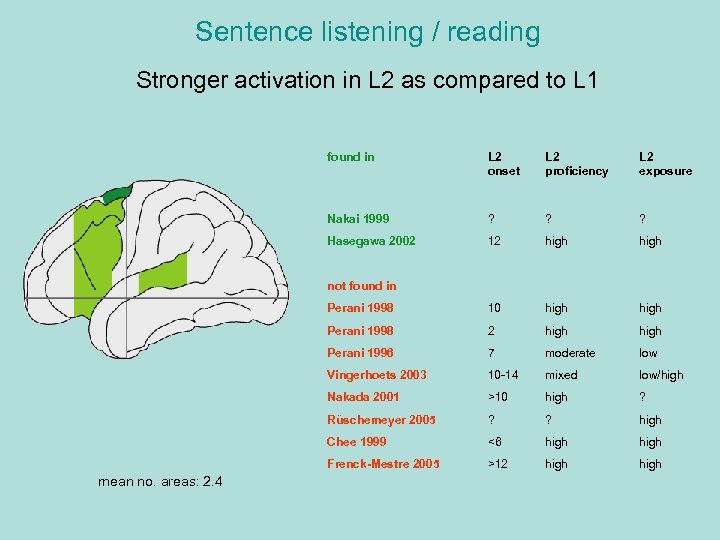

Sentence listening / reading Stronger activation in L 2 as compared to L 1 found in L 2 onset L 2 proficiency L 2 exposure Nakai 1999 ? ? ? Luke 2002 >10 high ? Perani 1998 10 high Perani 1998 2 high Perani 1996 7 moderate low Vingerhoets 2003 10 -14 mixed low/high Nakada 2001 >10 high ? Rüschemeyer 2005 ? ? high Chee 1999 <6 high Frenck-Mestre 2005 >12 high not found in mean no. areas: 2. 4

Sentence listening / reading Stronger activation in L 2 as compared to L 1 found in L 2 onset L 2 proficiency L 2 exposure Rüschemeyer 2005 ? ? high Luke 2002 >10 high ? Nakai 1999 ? ? ? Perani 1998 10 high Perani 1998 2 high Perani 1996 7 moderate low Vingerhoets 2003 10 -14 mixed low/high Nakada 2001 >10 high ? Chee 1999 <6 high Frenck-Mestre 2005 >12 high not found in mean no. areas: 2. 4

Sentence listening / reading Stronger activation in L 2 as compared to L 1 found in L 2 onset L 2 proficiency L 2 exposure Nakai 1999 ? ? ? Hasegawa 2002 12 high Perani 1998 10 high Perani 1998 2 high Perani 1996 7 moderate low Vingerhoets 2003 10 -14 mixed low/high Nakada 2001 >10 high ? Rüschemeyer 2005 ? ? high Chee 1999 <6 high Frenck-Mestre 2005 >12 high not found in mean no. areas: 2. 4

Sentence listening / reading Stronger activation in L 2 as compared to L 1 found in L 2 onset L 2 proficiency L 2 exposure Hasegawa 2002 12 high Luke 2002 >10 high ? Nakai 1999 ? ? ? Perani 1998 10 high Perani 1998 2 high Perani 1996 7 moderate low Vingerhoets 2003 10 -14 mixed low/high Nakada 2001 >10 high ? Rüschemeyer 2005 ? ? high Chee 1999 <6 high Frenck-Mestre 2005 >12 high not found in mean no. areas: 2. 4

Conclusions L 1 and L 2 sentence level comprehension recruit the same set of areas. Within this set of areas, there are to date no reliable activation level differences between L 1 and L 2 narrative comprehension. Stronger L 2 activation of the left posterior IFG may be found for speakers with late L 2 onset when additional judgment tasks are used. The left posterior IFG is the most likely candidate area for syntactic processing.

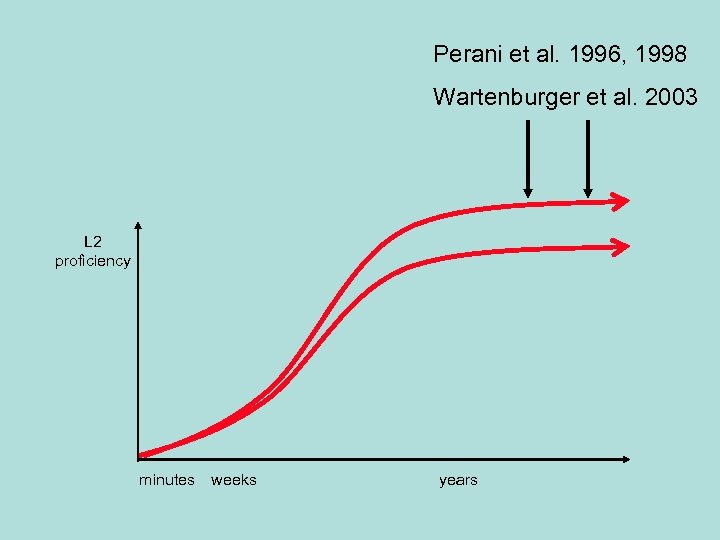

Perani et al. 1996, 1998 Wartenburger et al. 2003 L 2 proficiency minutes weeks years

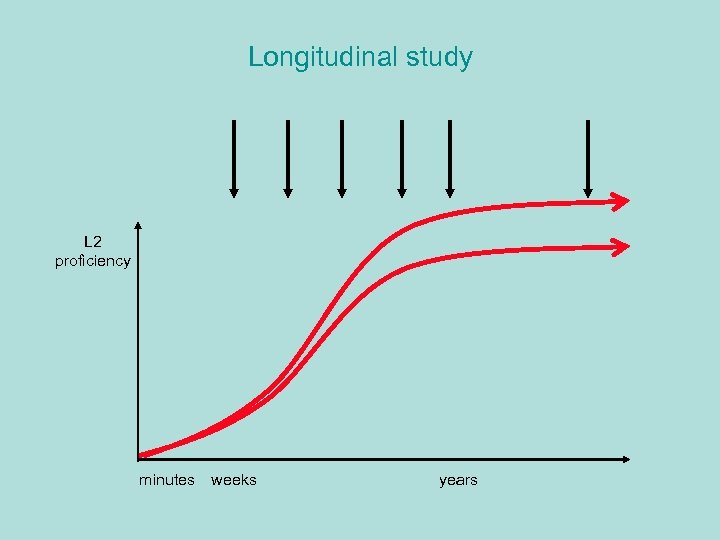

Longitudinal study L 2 proficiency minutes weeks years

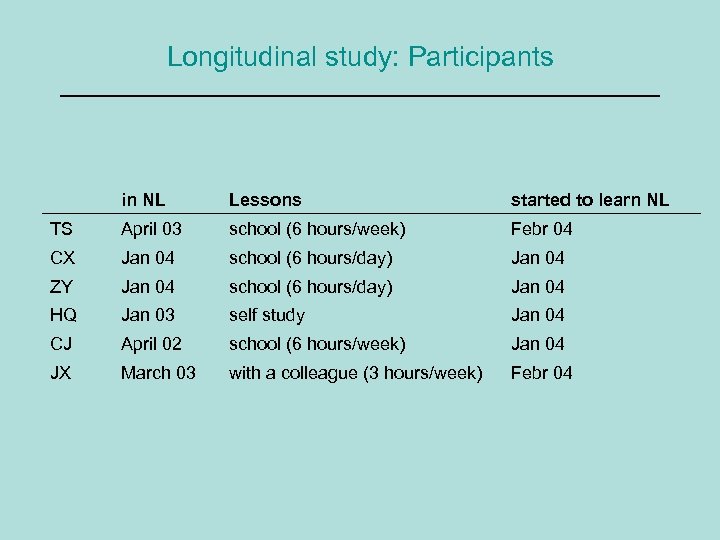

Longitudinal study: Participants in NL Lessons started to learn NL TS April 03 school (6 hours/week) Febr 04 CX Jan 04 school (6 hours/day) Jan 04 ZY Jan 04 school (6 hours/day) Jan 04 HQ Jan 03 self study Jan 04 CJ April 02 school (6 hours/week) Jan 04 JX March 03 with a colleague (3 hours/week) Febr 04

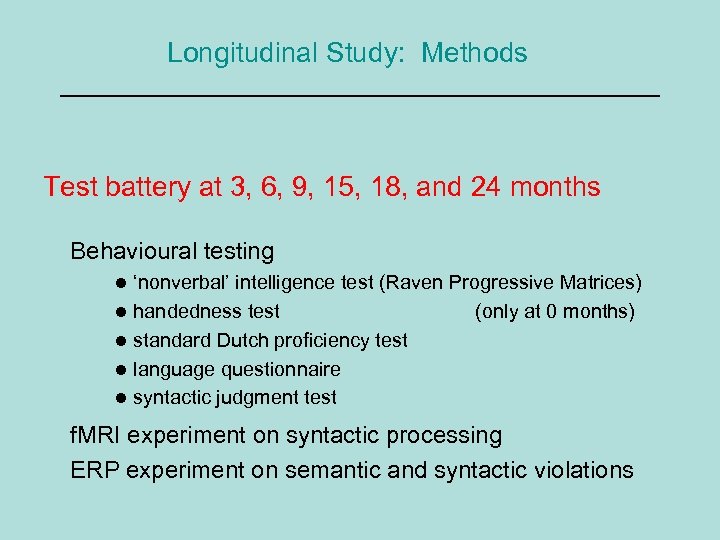

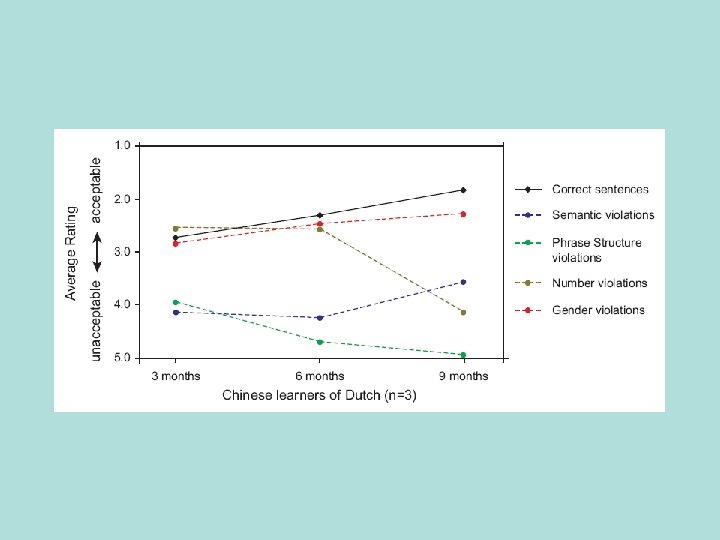

Longitudinal Study: Methods Test battery at 3, 6, 9, 15, 18, and 24 months Behavioural testing ‘nonverbal’ intelligence test (Raven Progressive Matrices) l handedness test (only at 0 months) l standard Dutch proficiency test l language questionnaire l syntactic judgment test l f. MRI experiment on syntactic processing ERP experiment on semantic and syntactic violations

S: (correct) De gele cirkel wordt door het blauwe vierkant weggestoten. Huang 2 yuan 2 quan 1 bei 4 lan 2 fang 1 kuai 4 tui 1 zou 3 The yellow circle is pushed away by the blue square away W: Het blauwe vierkant wordt door de gele cirkel weggestoten. Lan 2 fang 1 kuai 4 bei 4 huang 2 yuan 2 quan 1 tui 1 zou 3. The blue square is pushed away by the yellow circle. (incorrect) vierkant fang 1 kuai 4 square blauw lan 2 se 4 blue cirkel yuan 2 quan 1 circle geel huang 2 se 4 yellow wegstoten tui 1 zou 3 push away (correct) cirkel yuan 2 quan 1 circle geel huang 2 se 4 yellow cirkel yuan 2 quan 1 circle blauw lan 2 se 4 blue wegstoten tui 1 zou 3 push away (incorrect)

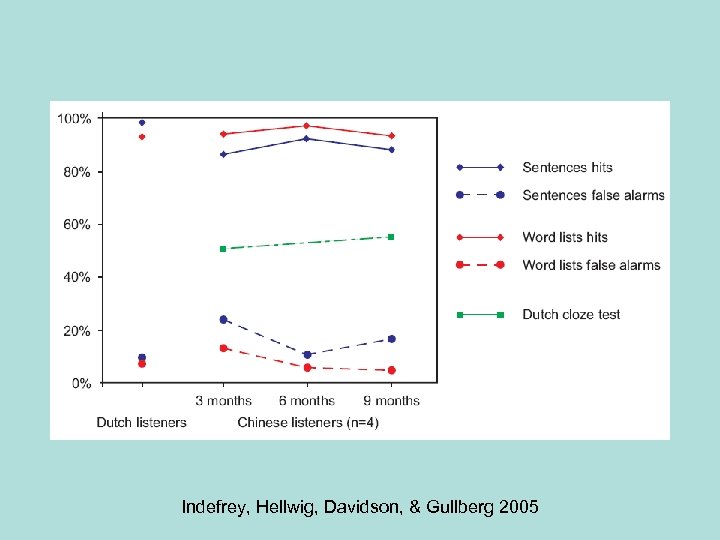

Indefrey, Hellwig, Davidson, & Gullberg 2005

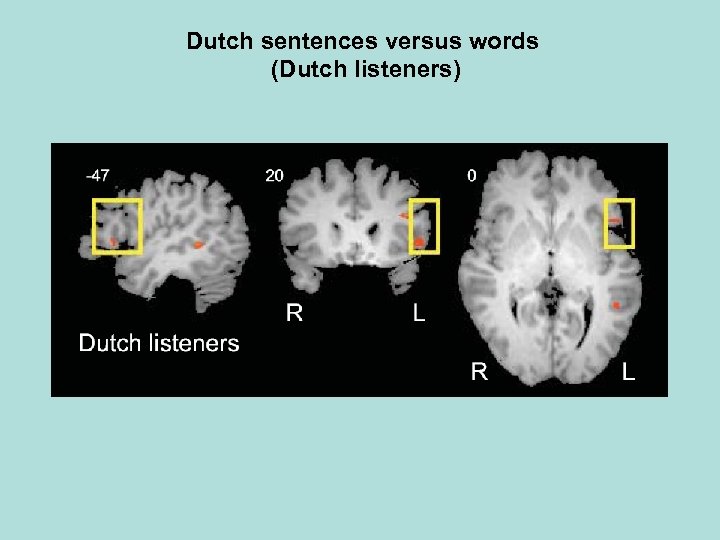

Dutch sentences versus words (Dutch listeners)

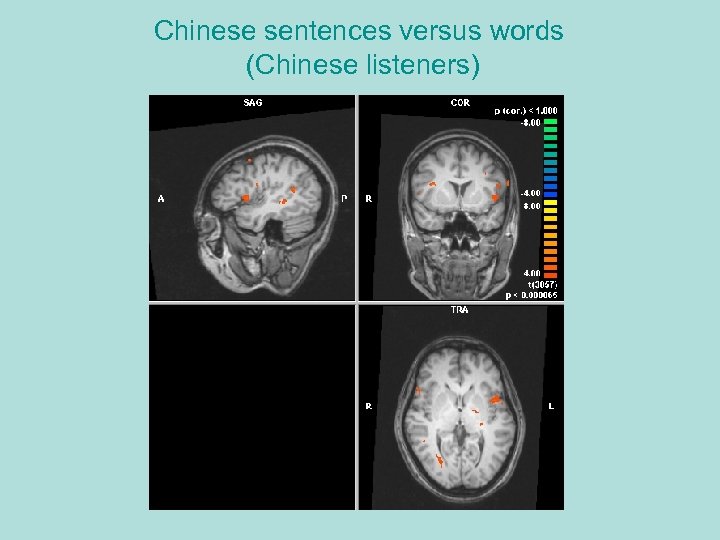

Chinese sentences versus words (Chinese listeners)

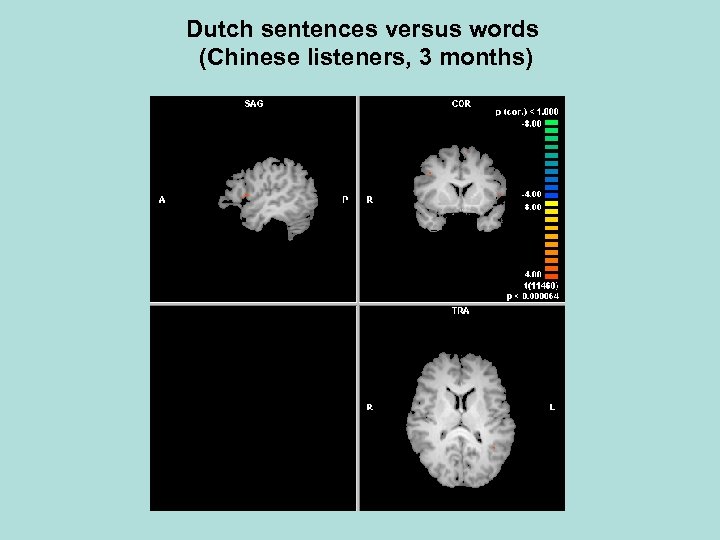

Dutch sentences versus words (Chinese listeners, 3 months)

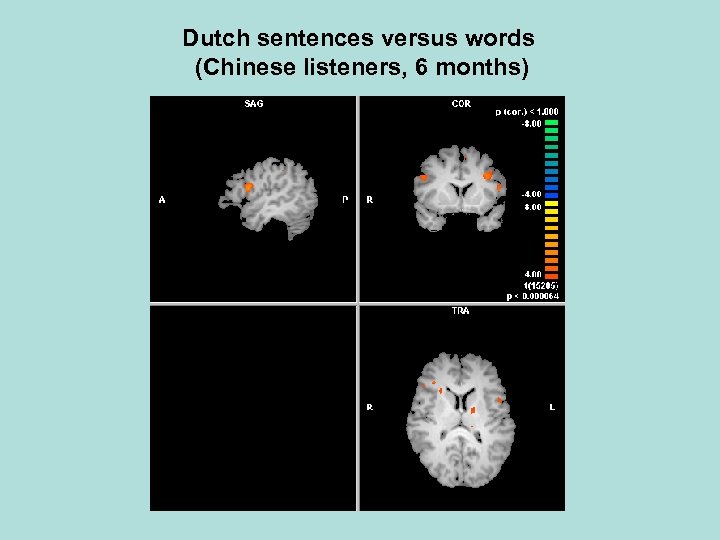

Dutch sentences versus words (Chinese listeners, 6 months)

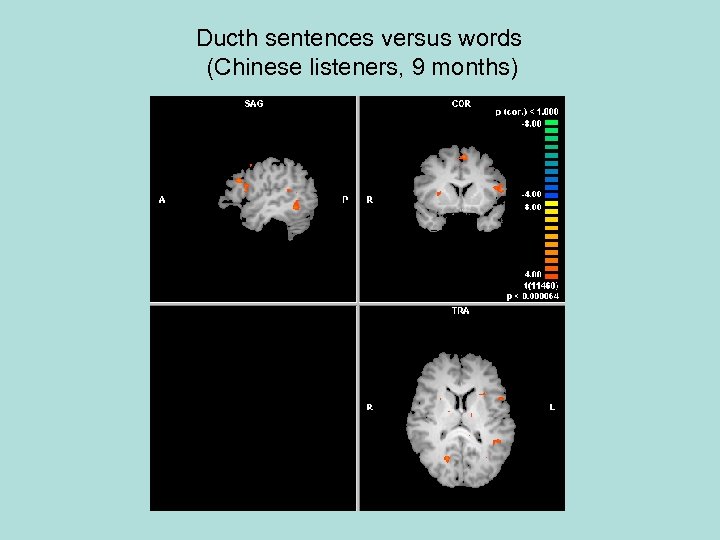

Ducth sentences versus words (Chinese listeners, 9 months)

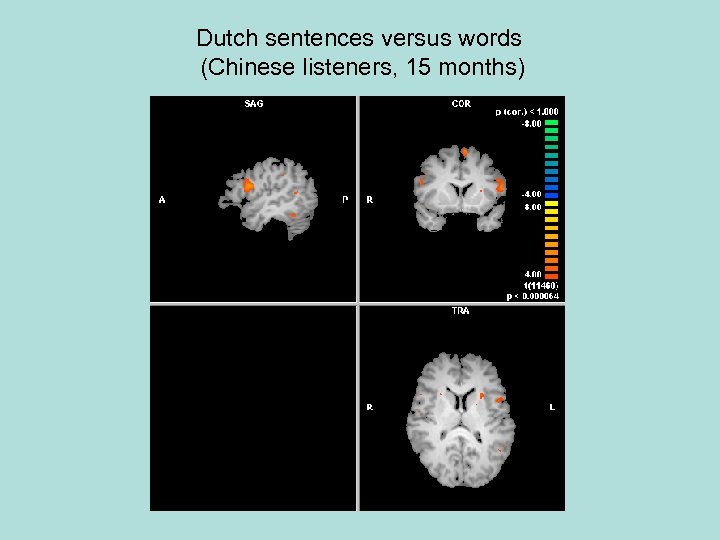

Dutch sentences versus words (Chinese listeners, 15 months)

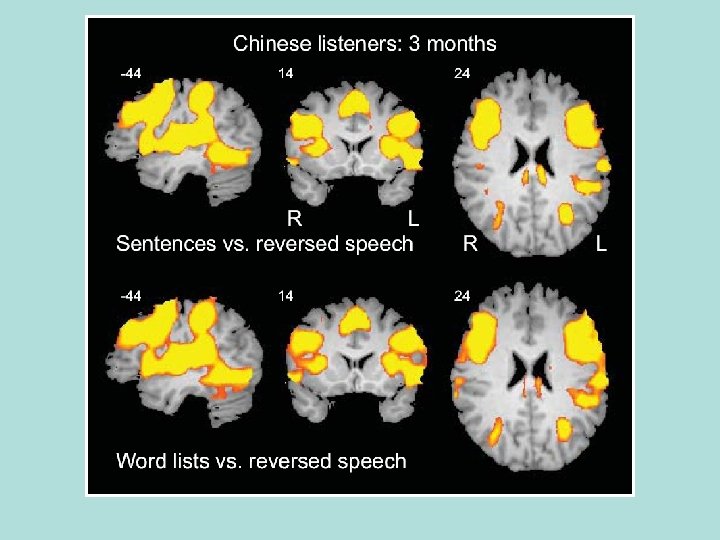

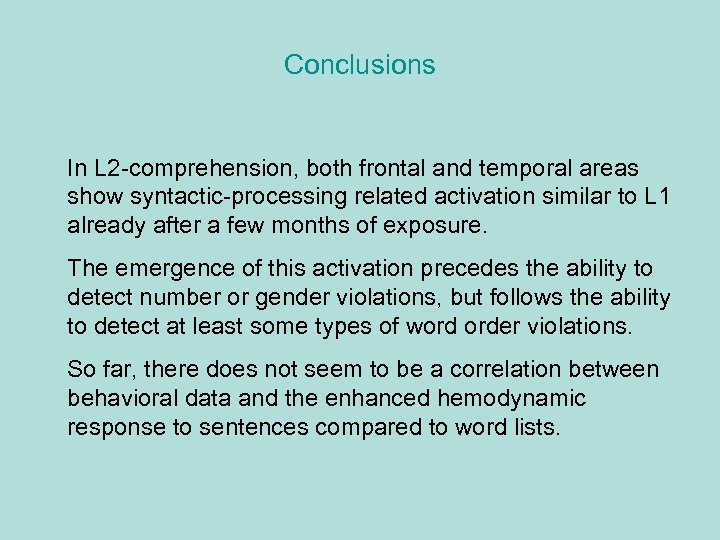

Conclusions In L 2 -comprehension, both frontal and temporal areas show syntactic-processing related activation similar to L 1 already after a few months of exposure. The emergence of this activation precedes the ability to detect number or gender violations, but follows the ability to detect at least some types of word order violations. So far, there does not seem to be a correlation between behavioral data and the enhanced hemodynamic response to sentences compared to word lists.

9481bad83e5d5d0252d1f32b46daf835.ppt