2983d1feb09484aa666f7e9d47b8f471.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 30

An Introduction to Bundling and Tying Eric Emch, OECD eric. emch@oecd. org 1

Overview of Talk I. Definitions: their use and abuse II. Procompetitive or neutral stories of tying/bundling III. Anticompetitive stories of tying/bundling IV. An example: U. S. v. Microsoft 2

Definitions • Tying: A firm conditioning purchase of its “tying” good on purchase of the “tied” good. • In a foreclosure story, the firm generally has market power in the “tying” good • Bundling: A firm offering a package of goods for sale as a single unit. • “Pure” bundling: Individual components not available separately • “Mixed” bundling: Individual components available separately, but package is discounted 3

Difference in Definitions • Tying can be seen as a requirements contract with variable proportions • Consumer must purchase all of its product B (tied good) from the firm if it wishes to purchase product A (tying good) from the firm. • Example: purchase of a cell phone often requires subsequent purchase of cell phone minutes from a single network. • Bundling can be seen as a requirements contract with fixed proportions, where the ratio of the two products is defined by the seller. • Example: Sales of car and car radio; sales of jet airplanes and SFE (seller furnished equipment, such as certain avionics equipment) 4

Difference in Economic Analysis • From the perspective of economics, the particular label: “tying” or “bundling, ” is not important. What is important is the economic theory of harm related to the behaviour, whatever it is labelled. 5

Difference in Economic Analysis (2) • • • An important point that should be remembered in all abuse of dominance cases is that, from the perspective of economics at least, it is more important to identify and develop an economic theory of harm that to categorize the form of the behaviour. Deciding which “box” the behaviour fits in: tying or bundling, fidelity rebates, predation or exclusive dealing may be important for legal reasons, but not for determining the effects of the behaviour. Economic analysis should focus on effects more than form. – Behaviours of similar form may have much different effects • For instance, tying as a price discrimination device compared to as a foreclosure device. – Behaviours of different forms may have similar effects • For instance, bundled discounts as a predatory device compared to pure price predation. Good reference on this point: Report by the EC Economic Advisory Group on Competition Policy: “An economic approach to Article 82” July 2005. Available at http: //ec. europa. eu/comm/competition/publications/studies/eagcp_july_21_05. pdf 6

Overview of Tying/Bundling • Bundling and tying are ubiquitous, and usually competitively innocuous – Defining a “product” for sale inherently involves bundling a set of components which may in theory be sold separately. A “car” is generally sold as a bundle of body, tires, radio, engine, etc. Each could in theory be sold separately. – The decision of how to define a product will depend on economies on the production and distribution side, as well as on the demand side. An “airplane” sold by Airbus or Boeing, for instance, often does not bundle a particular engine. That choice is made by the buyer. • Competition authorities generally should not intervene absent a compelling story of harm to competition 7

Types of Tying/Bundling • Contractual: An explicit or implied contract that requires use of a certain good B if good A is purchased. – For example, a contract that voids the warranty of a printer if non-manufacturer toner is used • Technical: Tie or bundle that is incorporated into the design of a product. – For example, technical incompatibility between Boeing 737 and non-Snecma engines Some commentators (e. g. , Carlton and Waldman 2007) have argued that competition enforcers should be more lenient towards technical tying than contractual tying, since the latter is more easily undone. 8

Procompetitive Motivations • Economies of scope in production or distribution – For instance, computer components are more efficiently assembled into working package by the manufacturer, who gives discount on “bundle” relative to buying components separately. • Demand-side economies of scope – Consumers may want “one stop shopping” – Rather than having to buy separately a car and the stereo system, for instance, they may prefer the convenience of driving home with both. • Preservation of quality/brand name – Apple has with one brief exception in its history made purchase of its operating system conditional on purchase of its hardware. It has monopoly power in neither. Allows it to keep tight control of design and protect the Apple brand image. 9

Procompetitive Motivations (2) • Preserves efficient product mix – In variable proportions context, the ability to mark up both components in parallel prevents inefficient (deadweight-loss-inducing) substitution – For instance, if a manufacturer sells both printers and printer service, and the latter is sold in a competitive market, any markups must come on the printer itself, which will induce consumers to inefficiently substitute service for new printers. The same total markup could be more efficiently distributed across both components if the manufacturer tied the two. 10

Procompetitive Motivations (3) • “Cournot effect”/non-strategic discounts – In the vertical context, this is generally known as a “reduction in double marginalization, ” referring to a drop in total markup after two monopoly stages in a vertical chain merge. – In the horizontal context, consider classic example from Antoine Cournot (1838). What would happen to pricing after a merger of producers of two complementary goods: copper and zinc for the production of brass? – When the two producers are separate, neither takes into account the impact of its price on the other producer. If they did take this impact into account, they would have an extra incentive to lower price to increase sales of the complement. Thus, the two producers each price higher than they would if they merged. – In the context of bundling, this may be a source of non-strategic “mixed bundling” – offering a discount if the consumer also purchases the other component from your firm. These bundled discounts might hurt competitors, but they are non-strategic: they are motivated by internalizing a pricing externality, which is a positive both for consumers and the firms. – For a detailed economic model of this phenomenon, see Economides and Salop (1992) 11

Tying/Bundling as Price Discrimination • Tying and bundling can be used as mechanisms by which a firm can better sort consumers by their type, allowing them to extract more money from consumers, but also bringing more consumers into the market. • Form #1: Bundling can be a way of “smoothing” demand for the product, allowing the firm to charge a higher average price. • Form #2: Tying an aftermarket good to can be used as a way of “metering” the usage of the foremarket good. • While perhaps not explicitly “procompetitive, ” this use of tying/bundling is at least competitively neutral. Generally, price discrimination has ambiguous welfare consequences. Unless it has a clear impact on competition, probably not in the purview of competition enforcement. 12

Bundling as Price Discrimination, via Smoothing Demand • Bundling can create more uniform demand (see, e. g. , Bakos and Brynjolfsson 1999) – Imagine 1, 000 products, consumers having uniform independent [0, 1] distribution of willingness to pay for each good (assume zero production costs). • Firm pricing each good individually will price each at. 5. Many consumers will not buy. Firm is limited in the rents it can extract and deadweight loss results. • A monopolist of all goods will sell a bundle at price of 500. All consumers buy and the monopolist will make more money. No deadweight loss at all. – Demand for bundle is 500 via law of large numbers • Even with much smaller number of products, bundling reduces dispersion of demand. Given some market power and some dispersion of demand, a firm might bundle to allow it to make more money by reducing somewhat the dispersion of demand 13

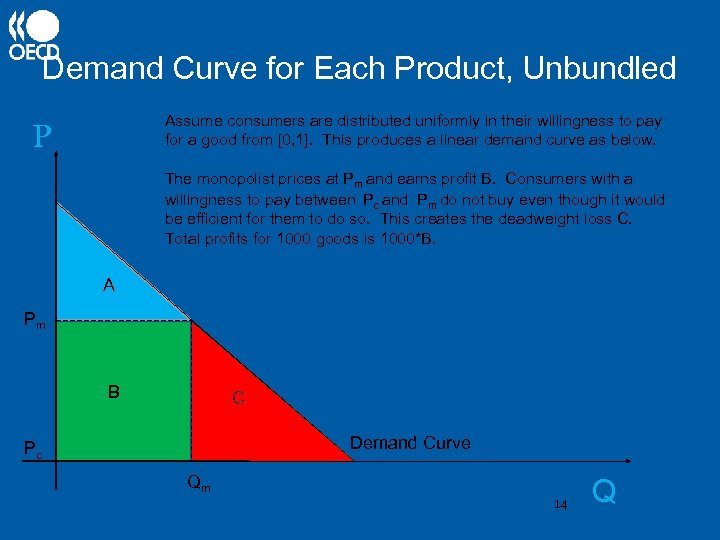

Demand Curve for Each Product, Unbundled Assume consumers are distributed uniformly in their willingness to pay for a good from [0, 1]. This produces a linear demand curve as below. P The monopolist prices at Pm and earns profit B. Consumers with a willingness to pay between Pc and Pm do not buy even though it would be efficient for them to do so. This creates the deadweight loss C. Total profits for 1000 goods is 1000*B. A Pm B C Demand Curve Pc Qm 14 Q

Demand Curve for All Products, Bundled P Demand curve becomes flat at the monopoly price for the bundled product Even though “per component” price is identical, firm increases profit by both eliminating deadweight loss and capturing consumer surplus Total profits roughly double in this example, incorporating former deadweight loss and former consumer surplus. Society is better off via elimination of DWL, be we’ve also lost all consumer surplus. Pm Demand Curve B Pc Qm 15 Q

Bundling with Correlation of Demand • Suppose demand is perfectly positively correlated: – Then, in above example, bundling brings no benefits over individual pricing – In general, positive correlation of demand works against this price discrimination aspect of bundling • Suppose demand is perfectly negatively correlated: – Then, only need two goods to extract all consumer surplus via bundling (demand for 2 -good bundle is uniform at. 5) – In general, negative correlation of demand promotes this price discrimination aspect of bundling 16

Tying as Metering Device • Imagine a package of foremarket and aftermarket goods, like printer and toner, or copiers and service. • A firm might want to price discriminate based on a consumer’s usage of the good. In many cases, however, it can’t achieve this sort of price discrimination directly in the foremarket. • An indirect way of price discriminating by usage may be to tie the products and raise price on the aftermarket good. • This may be the cause of some low foremarket + high aftermarket price patterns. See, e. g. , Emch (2003). 17

Anticompetitive Stories • Tying/bundling as a way to soften competition by increasing product differentiation • Tying/bundling as “foreclosure” – Committing to compete more aggressively – Denying competitors access to critical scale/scope economies 18

Tying/Bundling to Increase Product Differentiation • Tying competitive product (B) to monopoly product (A) can increase differentiation – Consumers that like A will purchase AB bundle from tying firm – Consumers do not want the A product will buy product B from rival firm, not from monopoly firm – Reduces competition in B good relative to no tying – May be profitable for monopolist under certain circumstances – Benefits both firms, probably may not actionable under competition laws if done unilaterally. May be more actionable if it represents a coordinated strategy to segment the market. • References: Carbajo, De Meza, and Seidman (1990) 19

Tying/Bundling as Foreclosure • Prime concern of antitrust enforcers • Tie or bundle denies critical scale/scope to competitor in a way that reduces competition and consumer welfare (will be explained in more detail below) • Be careful of naïve acceptance of competitor accusations of foreclosure. Several of the procompetitive/neutral stories of tying/bundling would hurt competitors, but are not considered “foreclosure” of competitors in a competition policy sense. 20

One Monopoly Rent Critique (1) • • Any credible story of tying must overcome the so-called one monopoly rent critique, which argues that a monopolist cannot increase its profits by using its monopoly power in one market to force consumers in a related, competitive market to take another of its goods. It is only literally true under a particular set of circumstances, but its basic logic provides a useful reality check that can reveal flaws in poorly defined tying stories. Consider the following setting: – Firm A is a monopolist in good A and also sells complementary good B in fixed proportions – Assume that market for good B is perfectly competitive with no entry costs and the consumers have uniform willingness to pay, U, for the pair of goods. In this circumstance, non-tying monopolist can charge U minus price (cost) of B Tying does not increase profits. Any increase in the price of B after the tie has to be compensated with a decrease in the price of A. 21

One Monopoly Rent Logic • Assume a competitive computer industry but a monopolist of operating systems • Consumers buy one of each in a package and value the package at V. Assume production cost per computer is C and production cost per OS is zero • Why would the operating system monopolist want to bundle? – Non-bundling outcome: Computer industry charges its cost C. OS seller can charge up to (V-C), and makes profit (V-C). – Bundling outcome: OS seller, assuming it has same costs C for producing computers, can charge V and makes profit (V-C). – No benefit to tying/bundling – there is one monopoly rent to extract. 22

One Monopoly Rent Critique (2) • Stepping away from the abstraction for a moment, the general idea illustrates why firms often do not tie complementary goods in practice, even when they are perfectly able to do so. • In fact, in many settings, a producer with market power will benefit from competition in the complement bringing variety and innovation and thus value to the package • Divergent strategies of Microsoft and Apple in operating systems. Microsoft benefitted from competition on the hardware side, which increased its market penetration relative to Apple in the 1990 s. 23

Limits of One Monopoly Rent Logic (1) • Fixed entry costs and alternative uses for the competitive good – Whinston (1990) shows that a monopolist might tie in order to commit itself to compete aggressively in the tied good. It cannot make profits unless it sells the package, so it will more aggressively take profits from the entrant. This may profitably deter entry. • Dynamic R&D expenditures – Choi (2002) adds an R&D stage to Winston model. Commitment to aggressive competition reduces incentives of other firms to stay in the market by investing in R&D • Note that in both of these models, competitive good is not complementary, but used by same group of consumers as monopoly good. 24

Limits of One Monopoly Rent Logic (2) • A more complete leveraging story with pure complementary goods is developed in Carlton and Waldman (2002) • An example of an important general idea: – if there are economies of scale in complementary good B, and economies of scope between good B and a third market C, then monopolization of good B may provide a route by which a monopolist of A can extend its monopoly to a new market C • Denying scale in an industry where scale is needed to be an effective competitor is a common theme behind foreclosure stories. Along with entry barriers. 25

Carlton/Waldman Model of Foreclosure • Two periods, two markets. Period 1 participation in complementary market (B) facilitates period 2 entry into monopoly market (A) • Monopolist benefits from complementary good in period 1, since it is able to extract some of the value consumer benefit from that entry. Thus would never tie if market A were impregnable • BUT, if period 1 entry into complementary market facilitates period 2 entry into monopoly market, may tie to protect market position in A • An example of economies of scale (in B) and scope (between A and B) being critical to foreclosure story 26

Application to U. S. v. Microsoft • U. S. alleged that Microsoft monopoly market (operating systems) protected by “applications barrier to entry” – No competing operating system could compete because would have few applications written to it, little value to consumer • Applications barrier to entry threatened by possibility of “middleware” that would run on top of operating system, facilitate cross-platform applications – Netscape browser / Java applications language was seen by Microsoft as a “middleware” threat. • Tie of operating system (A) to browser (B) was accomplished through various contractual and technical means (OEM contracts, OS default settings) 27

Application to U. S. v. Microsoft • Though Microsoft allows and extracts value from many complementary programs running on its operating system, this particular complement (B) was a potential future threat to its monopoly (A) • Tying helped to reduce market share of Netscape dramatically. Scale economies in developing complex software meant that in time Netscape could no longer keep up with Internet Explorer. Scale economies in A and scope economies between A & B are critical to the story of harm. 28

Final Thoughts • Tying and bundling is ubiquitous, and most often motivated by efficiencies. • Can often be used as a price discrimination device, but welfare implications are unclear. • True foreclosure stories are possible, but logic must be rigorously checked • Foreclosure, when it does occur, will often involve denying scale or scope economies to actual or potential competitors. This denial comes not through offering a superior product, but through denying critical scale or inputs to competitor via tying or bundling. 29

Some References • • Carlton, Dennis and Waldman, Michael, “Theories of Tying and Implications for Antitrust, ” in Wayne Dale Collins (ed. ), Economics of Antitrust, American Bar Association, (Forthcoming). Carlton, Dennis and Waldman, Michael, 2002, “The Strategic Use of Tying to Preserve and Create Market Power in Evolving Industries, 33 RAND Journal of Economics 194. Bakos, Y. and Brynjolfsson, 1999, "Bundling Information Goods: Pricing, Profits and Efficiency, " Management Science 45 (12), 1613. Carbajo, J. De Meza, D. and D. Seidman, 1990, “A Strategic Motivation for Commodity Bundling. 38 Journal of Industrial Economics 283. Choi , J. P. , 2004, “Tying and Innovation: A Dynamic Analysis of Tying Arrangements, ” 114 Econ. J. 102. Economides, Nicholas, and Salop, Steve, 1992, “Competition and Integration among Complements, and Network Market Structure, ” Journal of Industrial Economics, vol. XL, no. 1, pp. 105 -123. Emch, Eric, 2003, “Price Discrimination via Proprietary Aftermarkets, ” Contributions to Economic Analysis and Policy, Berkeley Electronic Press, vol. 2(1) Whinston, Michael, 1990, “Tying, Foreclosure, and Exclusion, ” 80 American Economic Review 837. 30

2983d1feb09484aa666f7e9d47b8f471.ppt