диалекты в америке.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 32

American English

American English

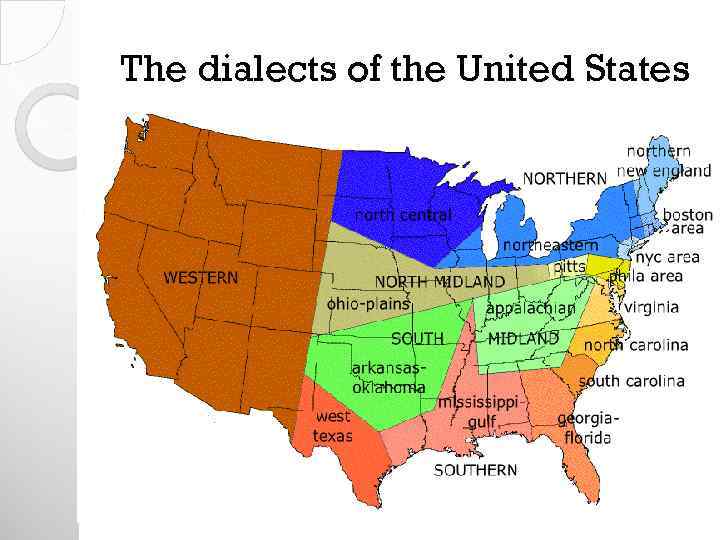

The dialects of the United States

The dialects of the United States

American English derives from 17 th century British English. Virginia and Massachusetts, the “original” colonies, were settled mostly by people from the south of England, especially London. The mid Atlantic area - Pennsylvania in particular - was settled by people from the north and west of England by the Scots -Irish (descendents of Scottish people who settled in Northern Ireland). These sources resulted in three dialect areas - northern, southern, and midland. Over time, further dialects would develop.

American English derives from 17 th century British English. Virginia and Massachusetts, the “original” colonies, were settled mostly by people from the south of England, especially London. The mid Atlantic area - Pennsylvania in particular - was settled by people from the north and west of England by the Scots -Irish (descendents of Scottish people who settled in Northern Ireland). These sources resulted in three dialect areas - northern, southern, and midland. Over time, further dialects would develop.

The Boston area and the Richmond and Charleston areas maintained strong commercial -- and cultural -- ties to England, and looked to London for guidance So, as the London dialect of the upper classes changed, so did the dialects of the upper class Americans in these areas. For example, in the late 1700’s and early 1800’s, r-dropping spread from London to much of southern England, and to places like Boston and Virginia. New Yorkers, who looked to Boston for the latest fashion trends, adopted it early, and in the south, it spread to wherever the plantation system was. On the other hand, in Pennsylvania, the Scots. Irish, and the Germans as well, kept their heavy r’s.

The Boston area and the Richmond and Charleston areas maintained strong commercial -- and cultural -- ties to England, and looked to London for guidance So, as the London dialect of the upper classes changed, so did the dialects of the upper class Americans in these areas. For example, in the late 1700’s and early 1800’s, r-dropping spread from London to much of southern England, and to places like Boston and Virginia. New Yorkers, who looked to Boston for the latest fashion trends, adopted it early, and in the south, it spread to wherever the plantation system was. On the other hand, in Pennsylvania, the Scots. Irish, and the Germans as well, kept their heavy r’s.

New York City became the door to the United States in the 1800’s, and we see the impact of other immigrants, such as Jews and Italians There is also a western dialect, which developed in the late 1800’s. It is literally a blend of all the dialects, although it is most influenced by the northern midland dialect. Out west, there were also the influences of non-English speaking people, notably the original Spanish speaking populations and the immigrant Chinese (mostly Cantonese).

New York City became the door to the United States in the 1800’s, and we see the impact of other immigrants, such as Jews and Italians There is also a western dialect, which developed in the late 1800’s. It is literally a blend of all the dialects, although it is most influenced by the northern midland dialect. Out west, there were also the influences of non-English speaking people, notably the original Spanish speaking populations and the immigrant Chinese (mostly Cantonese).

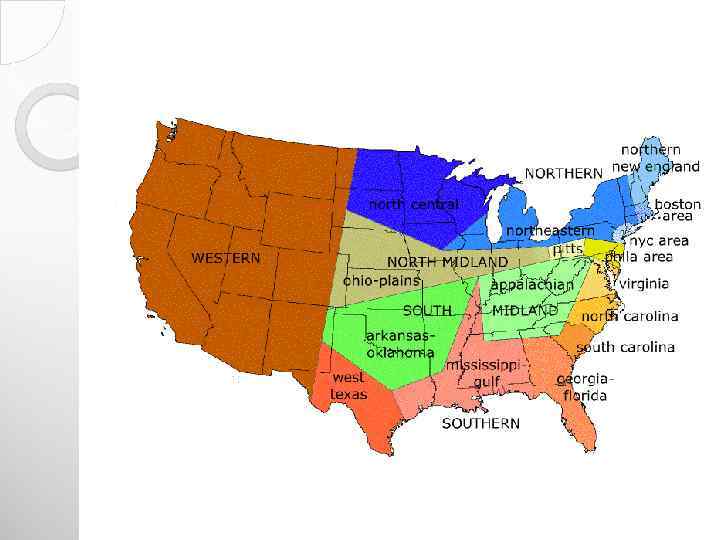

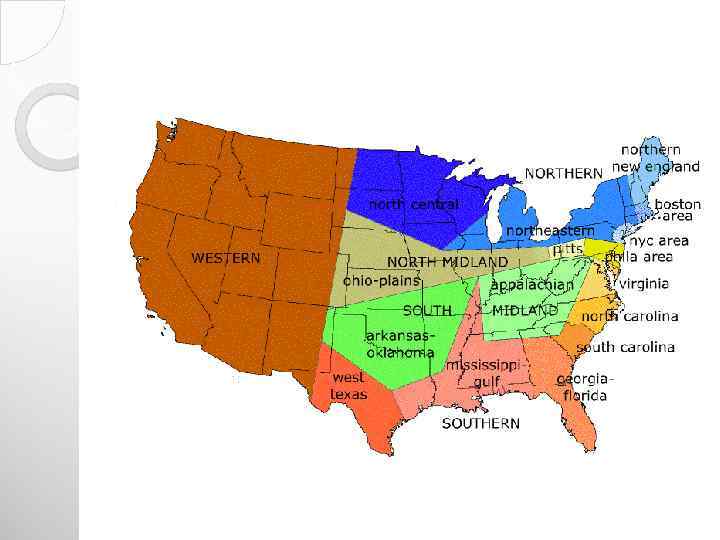

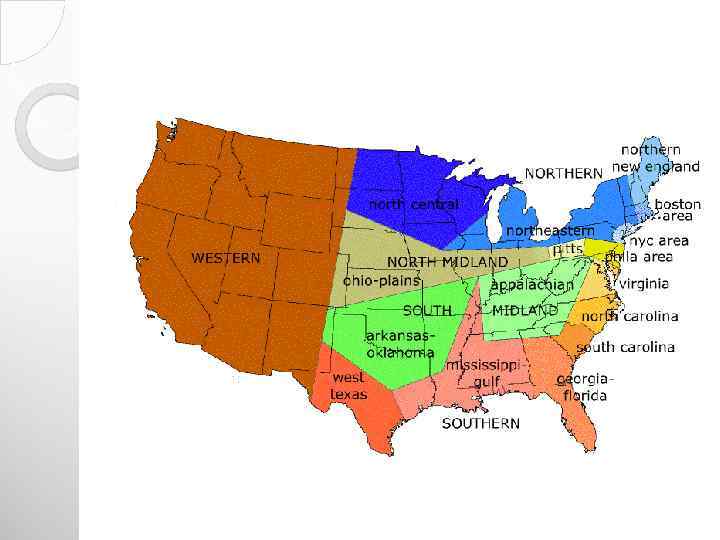

The dialects of the United States (with approximate areas): Northern Inland North central (upper Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, the Dakotas) Northern New England (Maine and New Hampshire) Western New England

The dialects of the United States (with approximate areas): Northern Inland North central (upper Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, the Dakotas) Northern New England (Maine and New Hampshire) Western New England

Northern North American English is more homogeneous. Most North American speech is rhotic

Northern North American English is more homogeneous. Most North American speech is rhotic

Inland North The Inland North dialect region was once considered the "standard Midwestern" speech that was the basis for General American in the mid-20 th century. the main feature of this dialect region is Northern Cities Vowel Shift The Inland North is centered on the area south of the Great Lakes, and consists of two components: to the east, central and western New York State; and to the west, much of Michigan's Lower Peninsula (Detroit, Grand Rapids), Toledo, Cleveland, Chicago, Gary, and Southeastern Wisconsin (Milwaukee, Racine, Kenosha).

Inland North The Inland North dialect region was once considered the "standard Midwestern" speech that was the basis for General American in the mid-20 th century. the main feature of this dialect region is Northern Cities Vowel Shift The Inland North is centered on the area south of the Great Lakes, and consists of two components: to the east, central and western New York State; and to the west, much of Michigan's Lower Peninsula (Detroit, Grand Rapids), Toledo, Cleveland, Chicago, Gary, and Southeastern Wisconsin (Milwaukee, Racine, Kenosha).

Northern Cities Vowel Shift The first stage is the raising, tensing, and diphthongization of /æ/ towards [ɪə]. "cat" = "kyat. " The second stage is the fronting of /ɑ/ to [aː] or even /æ thus block = black. In the third stage, /ɔ/ lowers towards [ɑ] The fourth stage is the backing and sometimes lowering of /ɛ/, toward either [ə] or [æ]. In the fifth stage, /ʌ/ is backed towards [ɔ] In the sixth stage, /ɪ/ is lowered and backed. However, it is kept distinct from [ɛ] in all contexts

Northern Cities Vowel Shift The first stage is the raising, tensing, and diphthongization of /æ/ towards [ɪə]. "cat" = "kyat. " The second stage is the fronting of /ɑ/ to [aː] or even /æ thus block = black. In the third stage, /ɔ/ lowers towards [ɑ] The fourth stage is the backing and sometimes lowering of /ɛ/, toward either [ə] or [æ]. In the fifth stage, /ʌ/ is backed towards [ɔ] In the sixth stage, /ɪ/ is lowered and backed. However, it is kept distinct from [ɛ] in all contexts

North Central The North Central dialect region extends from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan westward across northern Minnesota and North Dakota and into eastern Montana. The North Central is a linguistically conservative region; it participates in few of the major ongoing sound changes of North American English. The North Central region is stereotypically associated with a "sing-songy" intonation(the pitch accent pattern of the Scandinavian languages) Older speakers in the region may merge /w/ and /v/, making well sound like "vell“ Older and rural speakers may also merge /ð/ into /d/ and /θ/ into /t/.

North Central The North Central dialect region extends from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan westward across northern Minnesota and North Dakota and into eastern Montana. The North Central is a linguistically conservative region; it participates in few of the major ongoing sound changes of North American English. The North Central region is stereotypically associated with a "sing-songy" intonation(the pitch accent pattern of the Scandinavian languages) Older speakers in the region may merge /w/ and /v/, making well sound like "vell“ Older and rural speakers may also merge /ð/ into /d/ and /θ/ into /t/.

Western New England Western New England, encompassing most of Connecticut, western Massachusetts, and Vermont, has close historical ties to the Inland North: it is from Western New England that the westward migration began that led to the settlement of most upstate New York and the rest of the Inland North. some speakers show a general tendency in the direction of the Northern Cities Vowel Shift(/æ/ that is somewhat higher and tenser than average, an /ɑ/ that is fronter than /ʌ/, ) cot-caught merger - A phonemic merger in which the vowels in words such as "hot" and "doll" and in words such as "law" and "talk" are pronounced identically, making the words "cot" and "caught" homophones. In Connecticut /ɑ/ and /ɔ/ remain distinct

Western New England Western New England, encompassing most of Connecticut, western Massachusetts, and Vermont, has close historical ties to the Inland North: it is from Western New England that the westward migration began that led to the settlement of most upstate New York and the rest of the Inland North. some speakers show a general tendency in the direction of the Northern Cities Vowel Shift(/æ/ that is somewhat higher and tenser than average, an /ɑ/ that is fronter than /ʌ/, ) cot-caught merger - A phonemic merger in which the vowels in words such as "hot" and "doll" and in words such as "law" and "talk" are pronounced identically, making the words "cot" and "caught" homophones. In Connecticut /ɑ/ and /ɔ/ remain distinct

Northeastern dialects Eastern New England Rhode Island New York City New Jersey Pennsylvania (Philadelphia and the Delaware Valley, Other parts of Pennsylvania) Baltimore, Maryland

Northeastern dialects Eastern New England Rhode Island New York City New Jersey Pennsylvania (Philadelphia and the Delaware Valley, Other parts of Pennsylvania) Baltimore, Maryland

Northeastern dialects non-rhoticity a split of /æ/ into two separate phonemes. dialects retain a distinction between historical short o and long o before intervocalic /r/ orange, Florida different from story and chorus.

Northeastern dialects non-rhoticity a split of /æ/ into two separate phonemes. dialects retain a distinction between historical short o and long o before intervocalic /r/ orange, Florida different from story and chorus.

Eastern New England The Eastern New England dialect area encompasses Maine, New Hampshire, and eastern Massachusetts (including Greater Boston). Canadian raising of /aɪ/ minimal fronting of /aʊ/ and /oʊ/ had more contact with British varieties of English (being nearer to the Atlantic coast) and looked to England as a standard of prestige for their speech. non-rhotic. have a class of words with "broad A"—that is, /aː/ as in father /æ/, such as bath, half, and can't.

Eastern New England The Eastern New England dialect area encompasses Maine, New Hampshire, and eastern Massachusetts (including Greater Boston). Canadian raising of /aɪ/ minimal fronting of /aʊ/ and /oʊ/ had more contact with British varieties of English (being nearer to the Atlantic coast) and looked to England as a standard of prestige for their speech. non-rhotic. have a class of words with "broad A"—that is, /aː/ as in father /æ/, such as bath, half, and can't.

Rhode Island non-rhoticity A key linguistic difference is that Rhode Island is subject to the father –bother merger A phonemic merger in English of the vowels /ɑː/ (as in father) and /ɒ/ (as in bother).

Rhode Island non-rhoticity A key linguistic difference is that Rhode Island is subject to the father –bother merger A phonemic merger in English of the vowels /ɑː/ (as in father) and /ɒ/ (as in bother).

New York City non-rhotic the highest realizations of /ɔ/ in North American English, approaching [oə] or even [ʊə] The accent is well attested in American movies and television shows

New York City non-rhotic the highest realizations of /ɔ/ in North American English, approaching [oə] or even [ʊə] The accent is well attested in American movies and television shows

Pennsylvania Philadelphia and the Delaware Valley rhotic /or/ of hoarse, mourning =/ɔr/ of horse, morning. "Water" is sometimes pronounced [wʊɾər], that is, with the vowel of wood orange, horrible are pronounced with /ɑr/ eight = eat, snake = sneak, slave = sleeve.

Pennsylvania Philadelphia and the Delaware Valley rhotic /or/ of hoarse, mourning =/ɔr/ of horse, morning. "Water" is sometimes pronounced [wʊɾər], that is, with the vowel of wood orange, horrible are pronounced with /ɑr/ eight = eat, snake = sneak, slave = sleeve.

The Midland North Midland South Midland St. Louis and vicinity Western Pennsylvania The region of the Midwestern United States west of the Appalachian Mountains begins the broad zone of what is generally called "Midland" speech. In older and traditional dialectological research, this is divided into two discrete subdivisions: the "North Midland" that begins north of the Ohio River valley area and the "South Midland" dialect area. In more recent work such as the Atlas of North American English, the former is designated simply "Midland" and the latter is reckoned as part of the South. The (North) Midland is arguably the major region whose dialect most closely approximates "General American".

The Midland North Midland South Midland St. Louis and vicinity Western Pennsylvania The region of the Midwestern United States west of the Appalachian Mountains begins the broad zone of what is generally called "Midland" speech. In older and traditional dialectological research, this is divided into two discrete subdivisions: the "North Midland" that begins north of the Ohio River valley area and the "South Midland" dialect area. In more recent work such as the Atlas of North American English, the former is designated simply "Midland" and the latter is reckoned as part of the South. The (North) Midland is arguably the major region whose dialect most closely approximates "General American".

The Midland distinctly fronter realization of the /oʊ/ phoneme (as in boat) than many other American accents the word on contains the phoneme /ɔ/ (as in caught) rather than /ɑ/ (as in cot). one of the names for the North-Midland boundary is the "'On' line". In some areas of the Midland, words like "roof" and "root“ = "book" and "hoof“

The Midland distinctly fronter realization of the /oʊ/ phoneme (as in boat) than many other American accents the word on contains the phoneme /ɔ/ (as in caught) rather than /ɑ/ (as in cot). one of the names for the North-Midland boundary is the "'On' line". In some areas of the Midland, words like "roof" and "root“ = "book" and "hoof“

St. Louis and vicinity /ɔr/ (as in for) = /ɑr/ (as in far) measure is pronounced /ˈmeɪʒ. ɚ/. Wash (as well as Washington) gains a /r/, becoming /wɔrʃ/ ("warsh"). "oil" and "joint" = awyul and jawynt /ð/ is often replaced with /d/ Get in that car over there sounds like Get in dat car over dere.

St. Louis and vicinity /ɔr/ (as in for) = /ɑr/ (as in far) measure is pronounced /ˈmeɪʒ. ɚ/. Wash (as well as Washington) gains a /r/, becoming /wɔrʃ/ ("warsh"). "oil" and "joint" = awyul and jawynt /ð/ is often replaced with /d/ Get in that car over there sounds like Get in dat car over dere.

![The city of Pittsburgh the monophthongization of /aʊ/ to [aː] downtown as The city of Pittsburgh the monophthongization of /aʊ/ to [aː] downtown as](https://present5.com/presentation/32523966_139311557/image-24.jpg) The city of Pittsburgh the monophthongization of /aʊ/ to [aː] downtown as "dahntahn“ /ʌ/ (as in cut); it approaches [ɑ]

The city of Pittsburgh the monophthongization of /aʊ/ to [aː] downtown as "dahntahn“ /ʌ/ (as in cut); it approaches [ɑ]

Southern American English as we know it today began to take its current shape only after World War II. Some generalizations include: The conditional merger of [ɛ] and [ɪ] before nasal consonants pin–pen merger. The diphthong /aɪ/ becomes monophthongized to /aː/. "I" → "Ah" Lax and tense vowels often merge before /l/ raising of initial vowel of [au] to [æu]; the initial vowel is often lengthened and prolonged, yielding [æːw]. nasalization of vowels, esp. diphthongs, before [n]. raising of [æ] to [e]; can't → cain't, etc. South Midlands speech is rhotic.

Southern American English as we know it today began to take its current shape only after World War II. Some generalizations include: The conditional merger of [ɛ] and [ɪ] before nasal consonants pin–pen merger. The diphthong /aɪ/ becomes monophthongized to /aː/. "I" → "Ah" Lax and tense vowels often merge before /l/ raising of initial vowel of [au] to [æu]; the initial vowel is often lengthened and prolonged, yielding [æːw]. nasalization of vowels, esp. diphthongs, before [n]. raising of [æ] to [e]; can't → cain't, etc. South Midlands speech is rhotic.

The Southern Drawl, or the diphthongization/triphthongization of the traditional short front vowels as in the words pat, pet, and pit: these develop a glide up from their original starting position to [j], and then in some cases back down to schwa. /æ/ → [æjə] /ɛ/ → [ɛjə] /ɪ/ → [ɪjə]

The Southern Drawl, or the diphthongization/triphthongization of the traditional short front vowels as in the words pat, pet, and pit: these develop a glide up from their original starting position to [j], and then in some cases back down to schwa. /æ/ → [æjə] /ɛ/ → [ɛjə] /ɪ/ → [ɪjə]

Southern vowel shift The back vowels /u/ in "boon" and /o/ in "code" shift considerably forward. The open back unrounded vowel /ɑr/ "card" =/ɔ/ "board", =/u/ in "boon".

Southern vowel shift The back vowels /u/ in "boon" and /o/ in "code" shift considerably forward. The open back unrounded vowel /ɑr/ "card" =/ɔ/ "board", =/u/ in "boon".

![New Orleans cot and caught as [kɑt] and [kɔt] curl–coil merger greeting New Orleans cot and caught as [kɑt] and [kɔt] curl–coil merger greeting](https://present5.com/presentation/32523966_139311557/image-29.jpg) New Orleans cot and caught as [kɑt] and [kɔt] curl–coil merger greeting "Where y'at" ("Where are you at? ", meaning "How are you? ") Miami accent contains a rhythm and pronunciation heavily influenced by Spanish

New Orleans cot and caught as [kɑt] and [kɔt] curl–coil merger greeting "Where y'at" ("Where are you at? ", meaning "How are you? ") Miami accent contains a rhythm and pronunciation heavily influenced by Spanish

Western Dialect California English Pacific Northwest English The Western United States is the largest dialect region in the United States, and the one with the fewest distinctive phonological features

Western Dialect California English Pacific Northwest English The Western United States is the largest dialect region in the United States, and the one with the fewest distinctive phonological features

![California English California vowel shift: Before /ŋ/, /ɪ/ is raised to [i], so California English California vowel shift: Before /ŋ/, /ɪ/ is raised to [i], so](https://present5.com/presentation/32523966_139311557/image-31.jpg) California English California vowel shift: Before /ŋ/, /ɪ/ is raised to [i], so "king" has the same vowel of "keen" rather than "kin“ /æ/ = [eə] or [ɪə] before nasal consonants. "ban" = /beən/. "thank" is pronounced "thaynk". "cat" sounds closer to "caht". "put" sounds more like "putt" can sound slightly similar to "pet“ "kettle" sounds like "cattle". "cot" and "caught" are moving closer to General American "caught".

California English California vowel shift: Before /ŋ/, /ɪ/ is raised to [i], so "king" has the same vowel of "keen" rather than "kin“ /æ/ = [eə] or [ɪə] before nasal consonants. "ban" = /beən/. "thank" is pronounced "thaynk". "cat" sounds closer to "caht". "put" sounds more like "putt" can sound slightly similar to "pet“ "kettle" sounds like "cattle". "cot" and "caught" are moving closer to General American "caught".

Pacific Northwest English "leg" and "lag" pronounced [leɪɡ]; "tang" pronounced [teɪŋ]. "egg" and "leg" are pronounced "ayg" and "layg". The Pacific Northwest also has some of the features of the California vowel shift and the Canadian vowel shift: /æ/ is raised and diphthongized to [eə] before nasals by some speaker (man) /æ/ is lowered in the direction of [a]

Pacific Northwest English "leg" and "lag" pronounced [leɪɡ]; "tang" pronounced [teɪŋ]. "egg" and "leg" are pronounced "ayg" and "layg". The Pacific Northwest also has some of the features of the California vowel shift and the Canadian vowel shift: /æ/ is raised and diphthongized to [eə] before nasals by some speaker (man) /æ/ is lowered in the direction of [a]