After Shakespeare Lecture 5 Plan Romanticism in the

l5_after_shakepeare.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 49

After Shakespeare Lecture 5

After Shakespeare Lecture 5

Plan Romanticism in the English literature. Cultural background, main representatives, literary tendencies. Victorian era. Cultural background, literary tendencies. Modernism in the English literature. Cultural background, main representatives, literary tendencies. Post-war era. Cultural background, literary tendencies. Peter Ackroyd. Nick Hornby.

Plan Romanticism in the English literature. Cultural background, main representatives, literary tendencies. Victorian era. Cultural background, literary tendencies. Modernism in the English literature. Cultural background, main representatives, literary tendencies. Post-war era. Cultural background, literary tendencies. Peter Ackroyd. Nick Hornby.

Romanticism. Cultural background Late 18th- early 19th c. The Romantic Age - opposed to the Age of Reason: more daring, individual and imaginative approach to life and literature 1789 – the French Revolution began 1832 – the First Reform Bill (the right to vote given to the middle class, but not the working class) 1750 – 1850 – industrial revolution in England agricultural society → industrial society home manufacturing → factory production

Romanticism. Cultural background Late 18th- early 19th c. The Romantic Age - opposed to the Age of Reason: more daring, individual and imaginative approach to life and literature 1789 – the French Revolution began 1832 – the First Reform Bill (the right to vote given to the middle class, but not the working class) 1750 – 1850 – industrial revolution in England agricultural society → industrial society home manufacturing → factory production

Romantic outlook Attempt to go beyond ordinary reality into deeper, less obvious, and more elusive levels of individual human existence Belief in intuition Emphasis on individual emotion rather than common experience Interest in humble life Belief in the healing power of the natural world Uniqueness of the individual Sensuous delight in both common and exotic things of the world Blend of intensely lived joy and dejection Yearning for ideal states of being Probing interest in mysterious and mystical experience

Romantic outlook Attempt to go beyond ordinary reality into deeper, less obvious, and more elusive levels of individual human existence Belief in intuition Emphasis on individual emotion rather than common experience Interest in humble life Belief in the healing power of the natural world Uniqueness of the individual Sensuous delight in both common and exotic things of the world Blend of intensely lived joy and dejection Yearning for ideal states of being Probing interest in mysterious and mystical experience

1765 - Bishop Thomas Percy publishes “Reliques of Ancient English Poetry” (a collection of ballads dating back to medieval times) Medieval atmosphere Sense of mystery The supernatural Themes of courage and valor, hatred and revenge, love and death

1765 - Bishop Thomas Percy publishes “Reliques of Ancient English Poetry” (a collection of ballads dating back to medieval times) Medieval atmosphere Sense of mystery The supernatural Themes of courage and valor, hatred and revenge, love and death

In the British context, the OED gives the first usage of the word ‘Romantic’ as 1812, when H.C. Robinson comments in a journal entry: ‘Coleridge’s first lecture … . He spoke of … a classification of poetry into ancient and romantic’. In 1814, a reviewer in the Monthly Review writes of a ‘chapter [which] divides European poetry into two schools, the classical, and the romantic’. In the New Monthly Review in 1823, appears the first listed use of the word ‘Romanticism’: ‘the dramatic heresy of romanticism’. In 1827, Thomas Carlyle speaks of the ‘grand controversy … between the Classicists and Romanticists’.

In the British context, the OED gives the first usage of the word ‘Romantic’ as 1812, when H.C. Robinson comments in a journal entry: ‘Coleridge’s first lecture … . He spoke of … a classification of poetry into ancient and romantic’. In 1814, a reviewer in the Monthly Review writes of a ‘chapter [which] divides European poetry into two schools, the classical, and the romantic’. In the New Monthly Review in 1823, appears the first listed use of the word ‘Romanticism’: ‘the dramatic heresy of romanticism’. In 1827, Thomas Carlyle speaks of the ‘grand controversy … between the Classicists and Romanticists’.

General tendencies It exalts individual aspirations and values above those of society, and is personal and subjective in inclination. It turns for inspiration to the Middle Ages (regarded earlier as barbaric), to earlier forms of language (e.g. in Old English poetry), to folklore and folk-tales, to the supernatural as a means of expressing ‘strange states of mind’, and to Nature, celebrating both its specificity and the spiritual and moral bond between humanity and the natural world.

General tendencies It exalts individual aspirations and values above those of society, and is personal and subjective in inclination. It turns for inspiration to the Middle Ages (regarded earlier as barbaric), to earlier forms of language (e.g. in Old English poetry), to folklore and folk-tales, to the supernatural as a means of expressing ‘strange states of mind’, and to Nature, celebrating both its specificity and the spiritual and moral bond between humanity and the natural world.

It generally follows Rousseau’s belief in human goodness and the innocence of children and ‘primitive’ peoples (‘the noble savage’), and is optimistic about human progress, whilst also registering the potential anomie involved in sustaining a Romantic sensibility in modern urbanising and industrialising societies.

It generally follows Rousseau’s belief in human goodness and the innocence of children and ‘primitive’ peoples (‘the noble savage’), and is optimistic about human progress, whilst also registering the potential anomie involved in sustaining a Romantic sensibility in modern urbanising and industrialising societies.

Aesthetically, it is characterised by the privileging of the Imagination rather than canonic models, by freedom of subject, form and style, by the elevation of feeling (‘Sensibility’) over reason (‘Sense’), and in poetry – arguably the dominant literary genre in the British context at least – by rejecting Augustan poetic diction, by the use of traditional forms (e.g. lyrics, songs and ballads) and by the quest for a simpler, more direct style.

Aesthetically, it is characterised by the privileging of the Imagination rather than canonic models, by freedom of subject, form and style, by the elevation of feeling (‘Sensibility’) over reason (‘Sense’), and in poetry – arguably the dominant literary genre in the British context at least – by rejecting Augustan poetic diction, by the use of traditional forms (e.g. lyrics, songs and ballads) and by the quest for a simpler, more direct style.

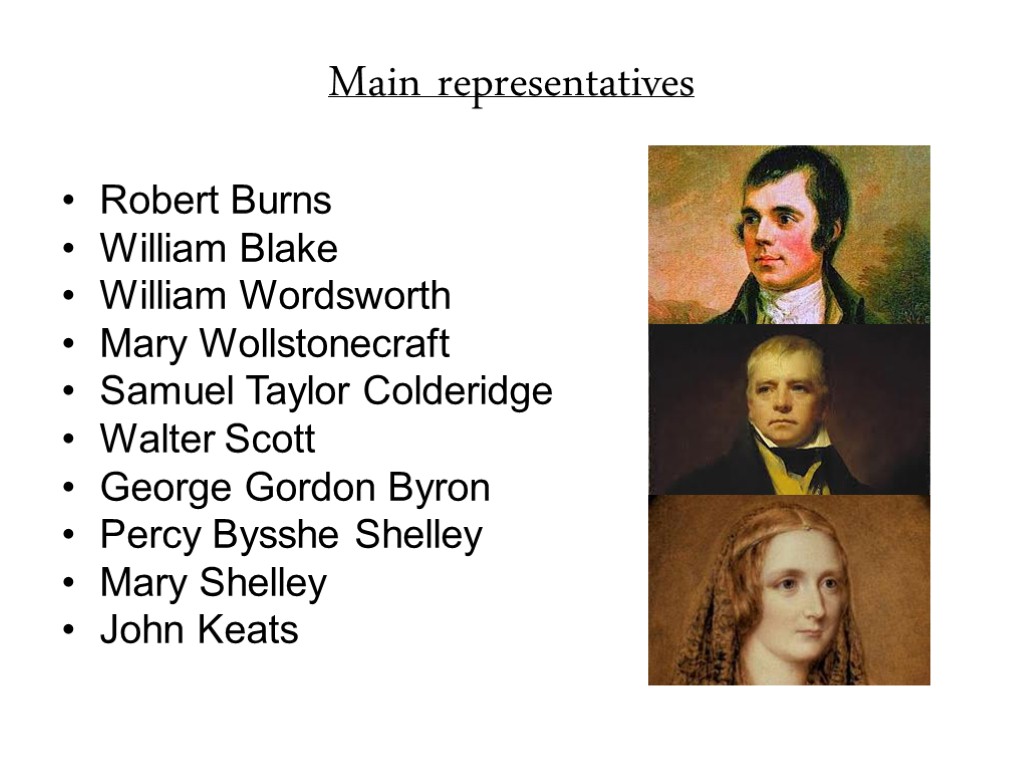

Main representatives Robert Burns William Blake William Wordsworth Mary Wollstonecraft Samuel Taylor Colderidge Walter Scott George Gordon Byron Percy Bysshe Shelley Mary Shelley John Keats

Main representatives Robert Burns William Blake William Wordsworth Mary Wollstonecraft Samuel Taylor Colderidge Walter Scott George Gordon Byron Percy Bysshe Shelley Mary Shelley John Keats

2 generations of Romantic poets: first: William Blake, Robert Burns, William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge; second: Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley, John Keats), but also the earlier poetry of Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning.

2 generations of Romantic poets: first: William Blake, Robert Burns, William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge; second: Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley, John Keats), but also the earlier poetry of Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning.

The period also contains: the ‘Gothic’ fiction of Ann Radcliffe, Matthew Lewis and Charles Maturin; the essays of Charles Lamb, William Hazlitt, Leigh Hunt and Thomas de Quincey; the fiction of Fanny Burney, Maria Edgeworth, Jane Austen, Sir Walter Scott, Mary Shelley, Thomas Love Peacock, but also, in its later years, novels by Edward Bulwer-Lytton and Benjamin Disraeli.

The period also contains: the ‘Gothic’ fiction of Ann Radcliffe, Matthew Lewis and Charles Maturin; the essays of Charles Lamb, William Hazlitt, Leigh Hunt and Thomas de Quincey; the fiction of Fanny Burney, Maria Edgeworth, Jane Austen, Sir Walter Scott, Mary Shelley, Thomas Love Peacock, but also, in its later years, novels by Edward Bulwer-Lytton and Benjamin Disraeli.

Victorian era. Cultural background Queen Victoria Queen of the United Kingdom Empress of India Mother of nine Her monarchy – a symbol of respectability, self-righteousness, conservatism, domestic virtues Britain controlled more of the earth than any other country in history 1780 – 1840: the British perfected the factory system for mass-producing goods, the practice of making interchangeable parts, the system of railroads Middle class dominated England commercially (self-made people, proud of their hard work, thrift, intensely religious)

Victorian era. Cultural background Queen Victoria Queen of the United Kingdom Empress of India Mother of nine Her monarchy – a symbol of respectability, self-righteousness, conservatism, domestic virtues Britain controlled more of the earth than any other country in history 1780 – 1840: the British perfected the factory system for mass-producing goods, the practice of making interchangeable parts, the system of railroads Middle class dominated England commercially (self-made people, proud of their hard work, thrift, intensely religious)

1832 – the First Reform Bill (the right to vote given to the middle class) 1867 – the Second Reform Bill (the right to vote given to some of the workers) Tension between financial growth and social instability Literary Developments New readers Legislation to protect writers’ copyright began to be introduced (1833, 1839, 1842 and so on) Love for nature + scientific precision Medieval past + social significance (Tennyson’s “The Passing of King Arthur”) Strong sense of public responsibility

1832 – the First Reform Bill (the right to vote given to the middle class) 1867 – the Second Reform Bill (the right to vote given to some of the workers) Tension between financial growth and social instability Literary Developments New readers Legislation to protect writers’ copyright began to be introduced (1833, 1839, 1842 and so on) Love for nature + scientific precision Medieval past + social significance (Tennyson’s “The Passing of King Arthur”) Strong sense of public responsibility

Literary tendencies close connection between Victorian literature and its historical background a constant awareness of the duty of the writer as interpreter, often as popularizer, of the intellectual issues of the times The typical progression of thought was that of Ruskin, moving from a purely artistic interest to awareness of a world unfit for art to an attempt to reform that world and make it a decent place for the joint habitation of man and art

Literary tendencies close connection between Victorian literature and its historical background a constant awareness of the duty of the writer as interpreter, often as popularizer, of the intellectual issues of the times The typical progression of thought was that of Ruskin, moving from a purely artistic interest to awareness of a world unfit for art to an attempt to reform that world and make it a decent place for the joint habitation of man and art

Prose fiction reached maturity in the widely-differing styles of Dickens, Thackeray, George Eliot, the Brontë sisters, Trollope, Meredith, Hardy, etc. Novel – the most popular form (“loose, baggy monsters” - Henry James) The Victorian era was the great age of the English novel - realistic, thickly plotted, crowded with characters, long. It was the ideal form to describe contemporary life and to entertain the middle class.

Prose fiction reached maturity in the widely-differing styles of Dickens, Thackeray, George Eliot, the Brontë sisters, Trollope, Meredith, Hardy, etc. Novel – the most popular form (“loose, baggy monsters” - Henry James) The Victorian era was the great age of the English novel - realistic, thickly plotted, crowded with characters, long. It was the ideal form to describe contemporary life and to entertain the middle class.

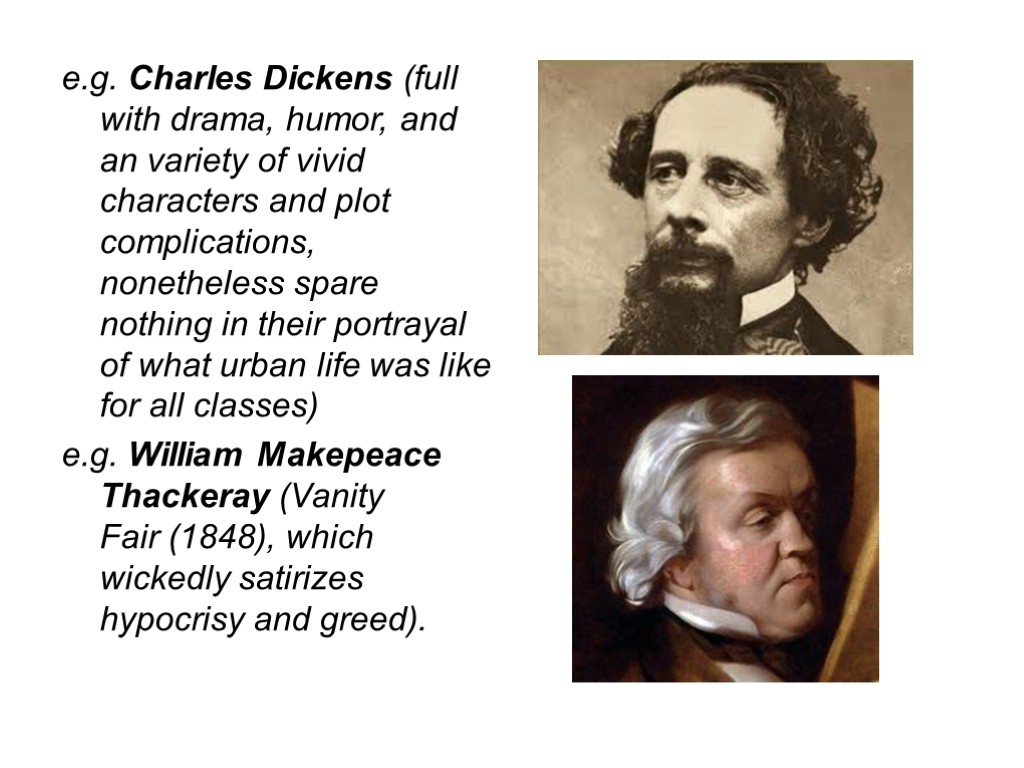

e.g. Charles Dickens (full with drama, humor, and an variety of vivid characters and plot complications, nonetheless spare nothing in their portrayal of what urban life was like for all classes) e.g. William Makepeace Thackeray (Vanity Fair (1848), which wickedly satirizes hypocrisy and greed).

e.g. Charles Dickens (full with drama, humor, and an variety of vivid characters and plot complications, nonetheless spare nothing in their portrayal of what urban life was like for all classes) e.g. William Makepeace Thackeray (Vanity Fair (1848), which wickedly satirizes hypocrisy and greed).

Emily Brontë - Wuthering Heights (1847), (elemental passions but controlled by an uncompromising artistic sense). Charlotte Brontë - Jane Eyre (1847) and Villette (1853), (more rooted in convention, but daring in their own ways). George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans) - appeared during the 1860s and 70s. (great erudition and moral fervor, ethical conflicts and social problems). George Meredith - novels noted for psychological perception.

Emily Brontë - Wuthering Heights (1847), (elemental passions but controlled by an uncompromising artistic sense). Charlotte Brontë - Jane Eyre (1847) and Villette (1853), (more rooted in convention, but daring in their own ways). George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans) - appeared during the 1860s and 70s. (great erudition and moral fervor, ethical conflicts and social problems). George Meredith - novels noted for psychological perception.

Anthony Trollope - famous for sequences of related novels that explore social, ecclesiastical, and political life in England Thomas Hardy - profoundly pessimistic novels are all set in the harsh, punishing midland county Wessex. Samuel Butler - novels satirizing the Victorian ethos Robert Louis Stevenson - arresting adventure fiction and children's verse. Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (Lewis Carroll) - complex and sophisticated children's classics Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking Glass (1871).

Anthony Trollope - famous for sequences of related novels that explore social, ecclesiastical, and political life in England Thomas Hardy - profoundly pessimistic novels are all set in the harsh, punishing midland county Wessex. Samuel Butler - novels satirizing the Victorian ethos Robert Louis Stevenson - arresting adventure fiction and children's verse. Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (Lewis Carroll) - complex and sophisticated children's classics Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking Glass (1871).

Lesser novelists of considerable merit include: Benjamin Disraeli, George Gissing, Elizabeth Gaskell, Wilkie Collins. By the end of the period, the novel was considered not only the premier form of entertainment but also a primary means of analyzing and offering solutions to social and political problems.

Lesser novelists of considerable merit include: Benjamin Disraeli, George Gissing, Elizabeth Gaskell, Wilkie Collins. By the end of the period, the novel was considered not only the premier form of entertainment but also a primary means of analyzing and offering solutions to social and political problems.

Nonfiction the great Whig historian Thomas Macaulay Thomas Carlyle, the historian, social critic, and prophet Influential thinkers included John Stuart Mill, the great liberal scholar and philosopher; Thomas Henry Huxley, a scientist and popularizer of Darwinian theory John Henry, Cardinal Newman, who wrote earnestly of religion, philosophy, and education founders of Communism, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels the great art historian and critic John Ruskin Matthew Arnold (his theories of literature and culture laid the foundations for modern literary criticism)

Nonfiction the great Whig historian Thomas Macaulay Thomas Carlyle, the historian, social critic, and prophet Influential thinkers included John Stuart Mill, the great liberal scholar and philosopher; Thomas Henry Huxley, a scientist and popularizer of Darwinian theory John Henry, Cardinal Newman, who wrote earnestly of religion, philosophy, and education founders of Communism, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels the great art historian and critic John Ruskin Matthew Arnold (his theories of literature and culture laid the foundations for modern literary criticism)

Poetry Alfred, Lord Tennyson - romantic in subject matter, his poetry was tempered by personal melancholy, in its mixture of social certitude and religious doubt it reflected the age. Robert Browning and his wife, Elizabeth Barrett Browning - immensely popular, though Elizabeth's was more venerated during their lifetimes. Browning is best remembered for his superb dramatic monologues. Rudyard Kipling, the poet of the empire triumphant, captured the quality of the life of the soldiers of British expansion. Some fine religious poetry was produced by Francis Thompson, Alice Meynell, Christina Rossetti, and Lionel Johnson. Pre-Raphaelites (William Morris, Christina Rossetti, Coventry Patmore), led by the painter-poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti - sought to revive what they judged to be the simple, natural values and techniques of medieval life and art. Their quest for a rich symbolic art led them away, however, from the mainstream.

Poetry Alfred, Lord Tennyson - romantic in subject matter, his poetry was tempered by personal melancholy, in its mixture of social certitude and religious doubt it reflected the age. Robert Browning and his wife, Elizabeth Barrett Browning - immensely popular, though Elizabeth's was more venerated during their lifetimes. Browning is best remembered for his superb dramatic monologues. Rudyard Kipling, the poet of the empire triumphant, captured the quality of the life of the soldiers of British expansion. Some fine religious poetry was produced by Francis Thompson, Alice Meynell, Christina Rossetti, and Lionel Johnson. Pre-Raphaelites (William Morris, Christina Rossetti, Coventry Patmore), led by the painter-poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti - sought to revive what they judged to be the simple, natural values and techniques of medieval life and art. Their quest for a rich symbolic art led them away, however, from the mainstream.

1890s - the decadents: Arthur Symons, Ernest Dowson, Oscar Wilde. - disgust with bourgeois complacency - extremes of behavior and expression. - pointed out the hypocrisies in Victorian values and institutions sparkling, witty style (comedies of Oscar Wilde, comic operettas of W. S. Gilbert and Sir Arthur Sullivan)

1890s - the decadents: Arthur Symons, Ernest Dowson, Oscar Wilde. - disgust with bourgeois complacency - extremes of behavior and expression. - pointed out the hypocrisies in Victorian values and institutions sparkling, witty style (comedies of Oscar Wilde, comic operettas of W. S. Gilbert and Sir Arthur Sullivan)

The Early Twentieth Century Irish drama (the Abbey Theatre in Dublin) William Butler Yeats (mythical themes) Sean O'Casey (political themes) George Bernard Shaw (social dramas)

The Early Twentieth Century Irish drama (the Abbey Theatre in Dublin) William Butler Yeats (mythical themes) Sean O'Casey (political themes) George Bernard Shaw (social dramas)

Early Victorian literature (Dickens, Thackeray, Bronte sisters) Later Victorian literature (Tennyson, Arnold, Browning, Hopkins, Eliot, Meredith, Hardy, Wilde, Shaw) satirical invective picturesqueness pronounced didacticism formation of mass culture move from revealing the social tendencies and outlining social types to creating a detailed psychological description of individuals (habits, clothes, diseases, occupation, inner life)

Early Victorian literature (Dickens, Thackeray, Bronte sisters) Later Victorian literature (Tennyson, Arnold, Browning, Hopkins, Eliot, Meredith, Hardy, Wilde, Shaw) satirical invective picturesqueness pronounced didacticism formation of mass culture move from revealing the social tendencies and outlining social types to creating a detailed psychological description of individuals (habits, clothes, diseases, occupation, inner life)

Modernism. Cultural background Reform bills – 1832, 1867, 1884 (+ 1928) House of Commons ← House of Lords “workshop of the world” negative aspects of factory system Education Act – 1870 Fin de siecle Modernism - ‘mental acceptance of modern values; to be of modern spirit or character’

Modernism. Cultural background Reform bills – 1832, 1867, 1884 (+ 1928) House of Commons ← House of Lords “workshop of the world” negative aspects of factory system Education Act – 1870 Fin de siecle Modernism - ‘mental acceptance of modern values; to be of modern spirit or character’

Literary tendencies Modernism - ‘mental acceptance of modern values; to be of modern spirit or character’ In the later part of the 19th Century, ‘modernism’ also defined a movement which sought to combine traditional beliefs with modern scientific and philosophical thought (Thomas Hardy used the word when he wrote of ‘the ache of modernism’ in Tess of the d’Urbervilles).

Literary tendencies Modernism - ‘mental acceptance of modern values; to be of modern spirit or character’ In the later part of the 19th Century, ‘modernism’ also defined a movement which sought to combine traditional beliefs with modern scientific and philosophical thought (Thomas Hardy used the word when he wrote of ‘the ache of modernism’ in Tess of the d’Urbervilles).

the principal period of Modernism was between 1900 and 1930 - ‘High Modernism’ – in literature between 1910 and 1930 - early initiatives of T. E. Hulme, Ezra Pound and the Imagist poets, - the production of major works by Henry James, Joseph Conrad, E. M. Forster, Eliot, W. B. Yeats, Joyce, Virginia Woolf, Dorothy Richardson, May Sinclair, D. H. Lawrence, Wyndham Lewis, Aldous Huxley

the principal period of Modernism was between 1900 and 1930 - ‘High Modernism’ – in literature between 1910 and 1930 - early initiatives of T. E. Hulme, Ezra Pound and the Imagist poets, - the production of major works by Henry James, Joseph Conrad, E. M. Forster, Eliot, W. B. Yeats, Joyce, Virginia Woolf, Dorothy Richardson, May Sinclair, D. H. Lawrence, Wyndham Lewis, Aldous Huxley

Anglo-American and Anglo-Irish nature of literary Modernism as indicated - international nature of the movement: very different nature in its different locales (for example, the reactionary ideology informing Anglo-American Modernism contra the revolutionary dynamics of Soviet Modernism) → transnational influences perceptible amongst many of the artists and writers

Anglo-American and Anglo-Irish nature of literary Modernism as indicated - international nature of the movement: very different nature in its different locales (for example, the reactionary ideology informing Anglo-American Modernism contra the revolutionary dynamics of Soviet Modernism) → transnational influences perceptible amongst many of the artists and writers

Modernism was not restricted to literature: all the major art forms (including the new medium of film) were involved in the movement. e.g. Eliot’s use of musical structure in The Waste Land e.g. Virginia Woolf’s experiments in the visual arts ↓ It is becoming customary to refer not to ‘Modernism’, but to ‘Modernisms’

Modernism was not restricted to literature: all the major art forms (including the new medium of film) were involved in the movement. e.g. Eliot’s use of musical structure in The Waste Land e.g. Virginia Woolf’s experiments in the visual arts ↓ It is becoming customary to refer not to ‘Modernism’, but to ‘Modernisms’

Modernists: seek to break with traditional forms and ideas, but are also hostile to the newly emerging ‘mass’ or ‘popular’ culture reject conventional forms of ‘realism’ in purporting to give an account of ‘things as they really are’ disruption of conventionally accepted forms of representation e.g. the novelists’ use of forms of ‘stream of consciousness’ to represent the workings of a character’s conscious and subconscious thoughtprocesses

Modernists: seek to break with traditional forms and ideas, but are also hostile to the newly emerging ‘mass’ or ‘popular’ culture reject conventional forms of ‘realism’ in purporting to give an account of ‘things as they really are’ disruption of conventionally accepted forms of representation e.g. the novelists’ use of forms of ‘stream of consciousness’ to represent the workings of a character’s conscious and subconscious thoughtprocesses

a concern with subject-matter which conveys ‘modern’ experience (often of living in an ‘alienating’ urban, industrial society and in the problematic dimension of Time), and which gives form to the interiority of such experience (the work of Freud and Jung especially is a central influence on many Modernists) they neverthess agree in the notion that there is a ‘reality’ to be grasped and represented, and that art is the medium in which this can most valuably be achieved. All these tendencies imply a humanistic sense of purpose and value which helps to distinguish Modernism from Postmodernism

a concern with subject-matter which conveys ‘modern’ experience (often of living in an ‘alienating’ urban, industrial society and in the problematic dimension of Time), and which gives form to the interiority of such experience (the work of Freud and Jung especially is a central influence on many Modernists) they neverthess agree in the notion that there is a ‘reality’ to be grasped and represented, and that art is the medium in which this can most valuably be achieved. All these tendencies imply a humanistic sense of purpose and value which helps to distinguish Modernism from Postmodernism

English Literary Modernism it was simultaneously highly innovative, not to say revolutionary, in its formal dimension, and reactionary in the ideology which underpinned it ideology of ‘cultural despair’ or ‘cultural pessimism’ the individual is profoundly alienated by and from the society to which s/he nevertheless is indissolubly tied

English Literary Modernism it was simultaneously highly innovative, not to say revolutionary, in its formal dimension, and reactionary in the ideology which underpinned it ideology of ‘cultural despair’ or ‘cultural pessimism’ the individual is profoundly alienated by and from the society to which s/he nevertheless is indissolubly tied

Henry James in 1896 wrote: ‘I have the imagination of disaster – and see life as ferocious and sinister’; Conrad thought in terms of the ‘darkness’ at the ‘heart’ of European civilisation and of modern life as ‘the destructive element’; Forster wrote of a world dominated by ‘panic and emptiness’, ‘telegrams and anger’; Lawrence saw artist as an exile who had to ‘fire his bombs’ into a corrupt world; Eliot presented post-war society as a sterile ‘Waste Land’ peopled by ‘Hollow Men’, Joyce had his artist-hero attempting to ‘fly by the nets’ which society ‘flings at his soul’ and to ‘escape the nightmare of history’; Woolf in To the Lighthouse has a section in which human achievements were destroyed as ‘Time Passes’

Henry James in 1896 wrote: ‘I have the imagination of disaster – and see life as ferocious and sinister’; Conrad thought in terms of the ‘darkness’ at the ‘heart’ of European civilisation and of modern life as ‘the destructive element’; Forster wrote of a world dominated by ‘panic and emptiness’, ‘telegrams and anger’; Lawrence saw artist as an exile who had to ‘fire his bombs’ into a corrupt world; Eliot presented post-war society as a sterile ‘Waste Land’ peopled by ‘Hollow Men’, Joyce had his artist-hero attempting to ‘fly by the nets’ which society ‘flings at his soul’ and to ‘escape the nightmare of history’; Woolf in To the Lighthouse has a section in which human achievements were destroyed as ‘Time Passes’

Imagist poets Ezra Pound, F. S. Flint, Richard Aldington, H. D. (Hilda Doolittle) and other Imagist poets promoted the idea of the ‘image’ (‘which presents an intellectual and emotional complex in an instant of time’) as the fundamental device in a poetry ‘that is hard and clear, never blurred or indefinite’, which seeks ‘concentration’, abjures ‘abstractions’ and ‘superfluous words’, and for the most part uses vers libre as its preferred verse form

Imagist poets Ezra Pound, F. S. Flint, Richard Aldington, H. D. (Hilda Doolittle) and other Imagist poets promoted the idea of the ‘image’ (‘which presents an intellectual and emotional complex in an instant of time’) as the fundamental device in a poetry ‘that is hard and clear, never blurred or indefinite’, which seeks ‘concentration’, abjures ‘abstractions’ and ‘superfluous words’, and for the most part uses vers libre as its preferred verse form

Ezra Pound In a Station of the Metro The apparition of these faces in the crowd; Petals on a wet, black bough. Alba As cool as the pale wet leaves of lily-of-the-valley She lay beside me in the dawn.

Ezra Pound In a Station of the Metro The apparition of these faces in the crowd; Petals on a wet, black bough. Alba As cool as the pale wet leaves of lily-of-the-valley She lay beside me in the dawn.

Techniques of modernist poetry (Pound, Eliot, Yeats) fragmentary images, symbols, motifs uses of myth ‘difficult’, highly allusive poetry experience of the ‘Modern City’ and the spiritual plight of contemporary Europe sought to give order and meaning to the ‘ruins’ of World War I and its aftermath

Techniques of modernist poetry (Pound, Eliot, Yeats) fragmentary images, symbols, motifs uses of myth ‘difficult’, highly allusive poetry experience of the ‘Modern City’ and the spiritual plight of contemporary Europe sought to give order and meaning to the ‘ruins’ of World War I and its aftermath

In the fiction (Joyce, Woolf, Sinclair, Richardson, Lawrence): a reaction against the realist concern with behaviour, action, dialogue and temporal narrative attempt to get below ‘the old stable ego of the character’ the extensive use of forms of ‘stream of consciouness’, ‘interior monologue’ and ‘free indirect speech’ in order at once to access characters’ mental processes and to give shape to their impressions and emotions. the principal focus was on the individual’s negotiations with a usually inimical social reality.

In the fiction (Joyce, Woolf, Sinclair, Richardson, Lawrence): a reaction against the realist concern with behaviour, action, dialogue and temporal narrative attempt to get below ‘the old stable ego of the character’ the extensive use of forms of ‘stream of consciouness’, ‘interior monologue’ and ‘free indirect speech’ in order at once to access characters’ mental processes and to give shape to their impressions and emotions. the principal focus was on the individual’s negotiations with a usually inimical social reality.

Post-war era. Cultural background The war cost upwards of 36 million lives worldwide (including six million Jews in the Holocaust, Hitler’s ‘ultimate solution’ for their extermination) the destructive capacity of the world’s super-powers had been immeasurably increased, especially by the invention of nuclear weapons; the balance of world power was now shared by America and the USSR (who dominated the whole of Eastern Europe); Germany (including Berlin) was divided into East and West, and occupied respectively by the Soviet Union and the Western Powers

Post-war era. Cultural background The war cost upwards of 36 million lives worldwide (including six million Jews in the Holocaust, Hitler’s ‘ultimate solution’ for their extermination) the destructive capacity of the world’s super-powers had been immeasurably increased, especially by the invention of nuclear weapons; the balance of world power was now shared by America and the USSR (who dominated the whole of Eastern Europe); Germany (including Berlin) was divided into East and West, and occupied respectively by the Soviet Union and the Western Powers

Although the term ‘post-war’ can be used to describe the period after any war, its contemporary currency is principally reserved for that following World War II It can define the entire subsequent period up to the present.

Although the term ‘post-war’ can be used to describe the period after any war, its contemporary currency is principally reserved for that following World War II It can define the entire subsequent period up to the present.

The arts - the ‘revolt into style’ of the emerging post-war youth culture: ‘bebop’ and ‘cool’ jazz (Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis); ‘rock and roll’ (Bill Haley, Fats Domino, Little Richard, Elvis Presley); Teddy Boys, Beatniks and so-called Angry Young Men (Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti; John Osborne, Kingsley Amis, Colin Wilson, John Wain); the first signs of ‘Pop Art’ in the visual arts (Eduardo Paolozzi, Jasper Johns, Peter Blake, Richard Hamilton, Jim Dine).

The arts - the ‘revolt into style’ of the emerging post-war youth culture: ‘bebop’ and ‘cool’ jazz (Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis); ‘rock and roll’ (Bill Haley, Fats Domino, Little Richard, Elvis Presley); Teddy Boys, Beatniks and so-called Angry Young Men (Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti; John Osborne, Kingsley Amis, Colin Wilson, John Wain); the first signs of ‘Pop Art’ in the visual arts (Eduardo Paolozzi, Jasper Johns, Peter Blake, Richard Hamilton, Jim Dine).

1960s The Swinging Sixties Pop-art Popular music (Beatles) boom in satire 1970s Terrorism Nuclear and Environmental Issues Punk’ counter-culture Visual Arts, development of Installation Art Theory and Criticism - rapid consolidation of Feminism, Marxism, Poststructuralism, Reader-Response theory, neo-Freudianism, and early essays in Deconstruction, Postmodernism and Postcolonialism.

1960s The Swinging Sixties Pop-art Popular music (Beatles) boom in satire 1970s Terrorism Nuclear and Environmental Issues Punk’ counter-culture Visual Arts, development of Installation Art Theory and Criticism - rapid consolidation of Feminism, Marxism, Poststructuralism, Reader-Response theory, neo-Freudianism, and early essays in Deconstruction, Postmodernism and Postcolonialism.

The Contemporary Period As Salman Rushdie, Midnight’s Children: ‘the further you get from the past, the more concrete and plausible it seems – but as you approach the present, it inevitably seems more and more incredible.’

The Contemporary Period As Salman Rushdie, Midnight’s Children: ‘the further you get from the past, the more concrete and plausible it seems – but as you approach the present, it inevitably seems more and more incredible.’

Peter Ackroyd Short Stories, Poetry, Non-Fiction, Fiction, Drama Biography a particular emphasis on exploring and chronicling the city of London, its history, literature, culture and people depicting the city's writers and artists as either fictional characters or biographical subjects: Charles Dickens, William Blake, Thomas More, Thomas Chatterton, John Milton, Oscar Wilde and T.S. Eliot. extensive, meticulous research, producing work that is extremely knowledgeable and scholarly combines intellectualism with a lively imaginative flair and an ability to present complex information and multi-faceted stories in an accessible, entertaining style

Peter Ackroyd Short Stories, Poetry, Non-Fiction, Fiction, Drama Biography a particular emphasis on exploring and chronicling the city of London, its history, literature, culture and people depicting the city's writers and artists as either fictional characters or biographical subjects: Charles Dickens, William Blake, Thomas More, Thomas Chatterton, John Milton, Oscar Wilde and T.S. Eliot. extensive, meticulous research, producing work that is extremely knowledgeable and scholarly combines intellectualism with a lively imaginative flair and an ability to present complex information and multi-faceted stories in an accessible, entertaining style

Ackroyd comments: 'London has always provided the landscape for my imagination. It becomes a character - a living being - within each of my books' (Peter Ackroyd profile, Guardian online: guardian.co.uk, 22 July 2008).

Ackroyd comments: 'London has always provided the landscape for my imagination. It becomes a character - a living being - within each of my books' (Peter Ackroyd profile, Guardian online: guardian.co.uk, 22 July 2008).

Nick Hornby English teacher Host for Samsung executives visiting the UK Journalist Pop Music Critic for the New Yorker 'Every English writer needs their corner that is forever England - but only a few brave men choose to make that corner Highbury. Who would have thought the square mile around Arsenal's stadium could be a suitable surrogate for the whole wide world?' Zadie Smith, Time

Nick Hornby English teacher Host for Samsung executives visiting the UK Journalist Pop Music Critic for the New Yorker 'Every English writer needs their corner that is forever England - but only a few brave men choose to make that corner Highbury. Who would have thought the square mile around Arsenal's stadium could be a suitable surrogate for the whole wide world?' Zadie Smith, Time

THE BIG BOOKS Nick's best-known books are the internationally bestselling novels High Fidelity, About A Boy, How To Be Good and A Long Way Down. Nick's non-fiction books include the football memoir Fever Pitch, a collection of essays on books and culture. He is also the author of Slam, which is vintage Hornby for teenagers. His latest book is Juliet, Naked, a novel about rock stars, relationships and last chances.

THE BIG BOOKS Nick's best-known books are the internationally bestselling novels High Fidelity, About A Boy, How To Be Good and A Long Way Down. Nick's non-fiction books include the football memoir Fever Pitch, a collection of essays on books and culture. He is also the author of Slam, which is vintage Hornby for teenagers. His latest book is Juliet, Naked, a novel about rock stars, relationships and last chances.

THE MOVIES Fever Pitch, High Fidelity and About A Boy have all been made into successful, and much-loved, films, starring Colin Firth, John Cusak and Hugh Grant. Fever Pitch was also released as a movie in 2005 starring Drew Barrymore. The filming of A Long Way Down is taking place, produced by Johnny Depp. Nick has also scripted the adaptation of Lynn Barber's memoir 'An Education'.

THE MOVIES Fever Pitch, High Fidelity and About A Boy have all been made into successful, and much-loved, films, starring Colin Firth, John Cusak and Hugh Grant. Fever Pitch was also released as a movie in 2005 starring Drew Barrymore. The filming of A Long Way Down is taking place, produced by Johnny Depp. Nick has also scripted the adaptation of Lynn Barber's memoir 'An Education'.

Writing as a job AN AVERAGE DAY: 'I have an office round the corner from my home. I arrive there between 9:30 and 10 a.m., smoke a lot, write in horrible little two-and-three sentence bursts, with five-minute breaks in between. Check for emails during each break, and get irritated if there aren't any. Go home for lunch. If I'm picking up my son I leave at 3:30. If not, I stay till six. It's all pretty grim! And so dull!'

Writing as a job AN AVERAGE DAY: 'I have an office round the corner from my home. I arrive there between 9:30 and 10 a.m., smoke a lot, write in horrible little two-and-three sentence bursts, with five-minute breaks in between. Check for emails during each break, and get irritated if there aren't any. Go home for lunch. If I'm picking up my son I leave at 3:30. If not, I stay till six. It's all pretty grim! And so dull!'