3eec7efd41332237d99fa7c3f1a2c53d.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 15

Advertising, Competition and Brand Names Chapter 21: Advertising, Competition and Brand Names 1

Introduction • Advertising is a weapon in the competition between firms • Creating & securing a brand identity can be helpful to consumers – Consumers may have a taste for variety; each consumer may like a different version of a particular product – Advertising can match consumers with the version they most prefer – But advertising can also be an uninformative and wasteful form of competition • Evaluation of advertising’s competitive role requires an understanding or clear model of how advertising works • Consider a simple model where firms can either spend a little or a lot on advertising • If advertising by one firm largely cancels the advertising of its rival, then this can result in an “advertising” war with both firms spending excessively on advertising Chapter 21: Advertising, Competition and Brand Names 2

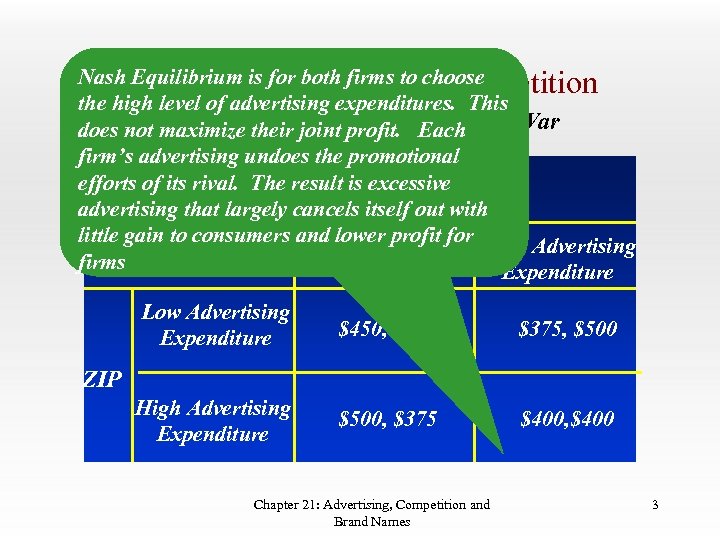

Nash Equilibrium is for both firms to choose Advertising as Wasteful Competition the high level of advertising expenditures. This Example of a Wasteful Each does not maximize their joint profit. Advertising War firm’s advertising undoes the promotional Gamma efforts of its rival. The result is excessive advertising that largely cancels itself out with little gain to consumers and lower profit for High Advertising Low Advertising firms Expenditure Low Advertising Expenditure $450, $450 $375, $500 High Advertising Expenditure $500, $375 $400, $400 ZIP Chapter 21: Advertising, Competition and Brand Names 3

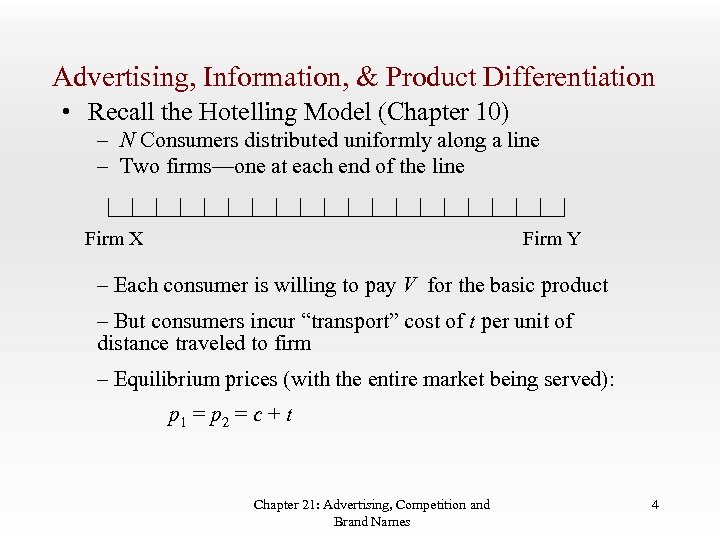

Advertising, Information, & Product Differentiation • Recall the Hotelling Model (Chapter 10) – N Consumers distributed uniformly along a line – Two firms—one at each end of the line Firm X Firm Y – Each consumer is willing to pay V for the basic product – But consumers incur “transport” cost of t per unit of distance traveled to firm – Equilibrium prices (with the entire market being served): p 1 = p 2 = c + t Chapter 21: Advertising, Competition and Brand Names 4

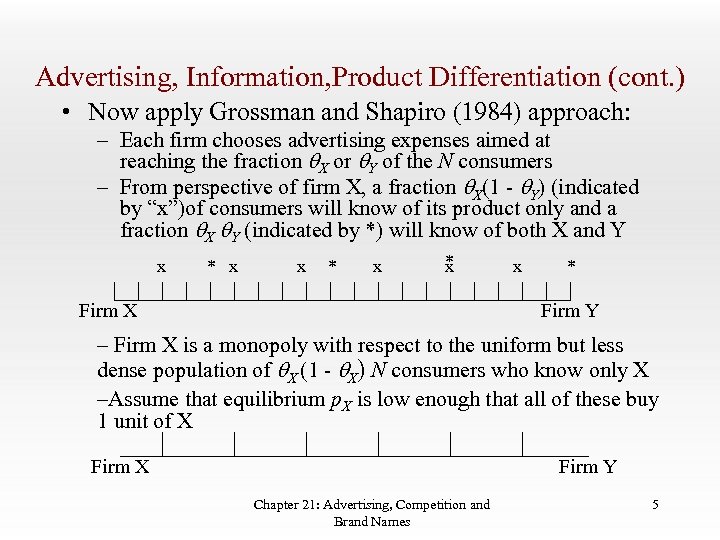

Advertising, Information, Product Differentiation (cont. ) • Now apply Grossman and Shapiro (1984) approach: – Each firm chooses advertising expenses aimed at reaching the fraction X or Y of the N consumers – From perspective of firm X, a fraction X(1 - Y) (indicated by “x”)of consumers will know of its product only and a fraction X Y (indicated by *) will know of both X and Y x * x * x Firm X x * Firm Y – Firm X is a monopoly with respect to the uniform but less dense population of X (1 - X) N consumers who know only X –Assume that equilibrium p. X is low enough that all of these buy 1 unit of X Firm Y Chapter 21: Advertising, Competition and Brand Names 5

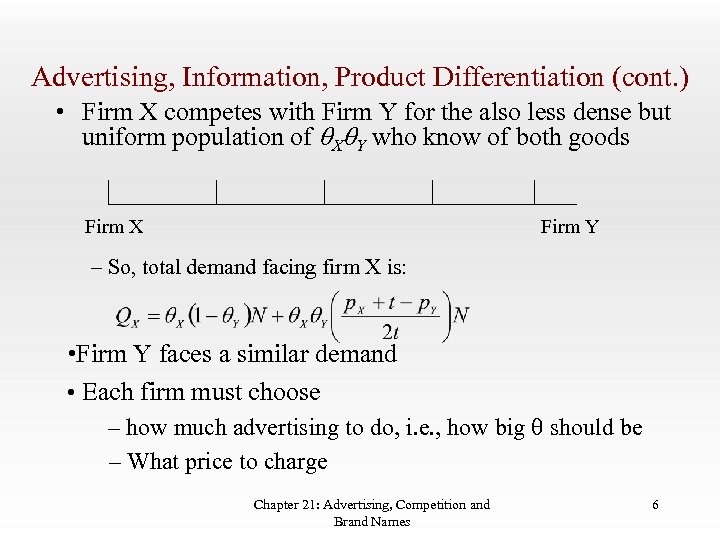

Advertising, Information, Product Differentiation (cont. ) • Firm X competes with Firm Y for the also less dense but uniform population of X Y who know of both goods Firm X Firm Y – So, total demand facing firm X is: • Firm Y faces a similar demand • Each firm must choose – how much advertising to do, i. e. , how big should be – What price to charge Chapter 21: Advertising, Competition and Brand Names 6

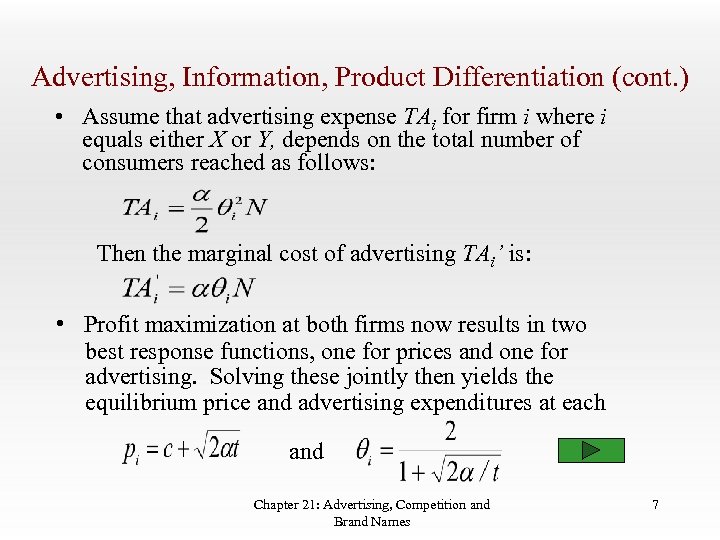

Advertising, Information, Product Differentiation (cont. ) • Assume that advertising expense TAi for firm i where i equals either X or Y, depends on the total number of consumers reached as follows: Then the marginal cost of advertising TAi’ is: • Profit maximization at both firms now results in two best response functions, one for prices and one for advertising. Solving these jointly then yields the equilibrium price and advertising expenditures at each and Chapter 21: Advertising, Competition and Brand Names 7

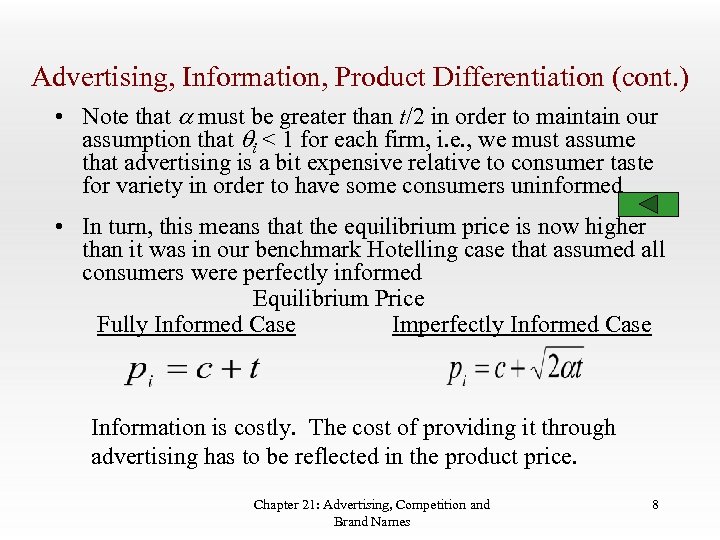

Advertising, Information, Product Differentiation (cont. ) • Note that must be greater than t/2 in order to maintain our assumption that i < 1 for each firm, i. e. , we must assume that advertising is a bit expensive relative to consumer taste for variety in order to have some consumers uninformed • In turn, this means that the equilibrium price is now higher than it was in our benchmark Hotelling case that assumed all consumers were perfectly informed Equilibrium Price Fully Informed Case Imperfectly Informed Case Information is costly. The cost of providing it through advertising has to be reflected in the product price. Chapter 21: Advertising, Competition and Brand Names 8

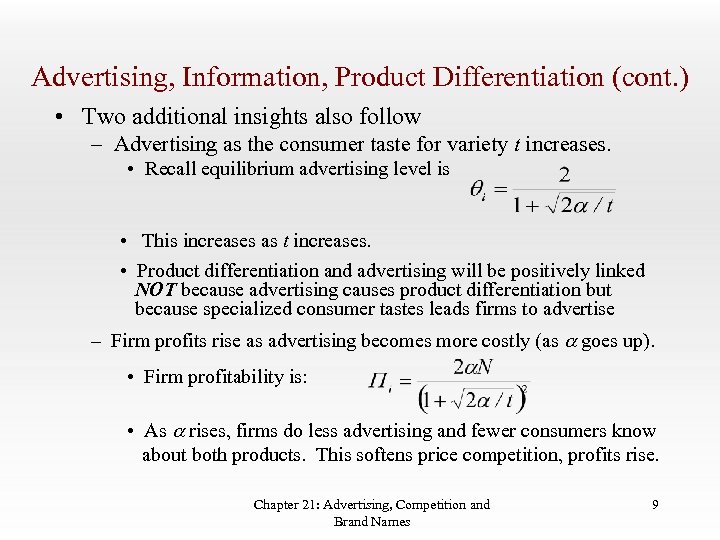

Advertising, Information, Product Differentiation (cont. ) • Two additional insights also follow – Advertising as the consumer taste for variety t increases. • Recall equilibrium advertising level is • This increases as t increases. • Product differentiation and advertising will be positively linked NOT because advertising causes product differentiation but because specialized consumer tastes leads firms to advertise – Firm profits rise as advertising becomes more costly (as goes up). • Firm profitability is: • As rises, firms do less advertising and fewer consumers know about both products. This softens price competition, profits rise. Chapter 21: Advertising, Competition and Brand Names 9

Building Brand Value vs Extending Brand Reach • Advertising in the Grossman and Shapiro model is pure information. This begs the question as to how advertising precisely works • Becker and Murphy (1993) argue that advertising works as a complement to the product, i. e. , it enhances consumer valuation of the good or service • Two ways complementary advertising can work – Consumers prefer to purchase brands that are well known, i. e. , advertising builds brand value in that consumers are willing to pay more for a well-known brand. This is close to an “advertising as persuasion” view – Advertising provides information that enhances product value, e. g. , where to go for related services such as hotels advertising nearby tourist sites. Here, advertising is truly informative and works therefore to bring in new customers, that is, to extend the brand’s market reach Chapter 21: Advertising, Competition and Brand Names 10

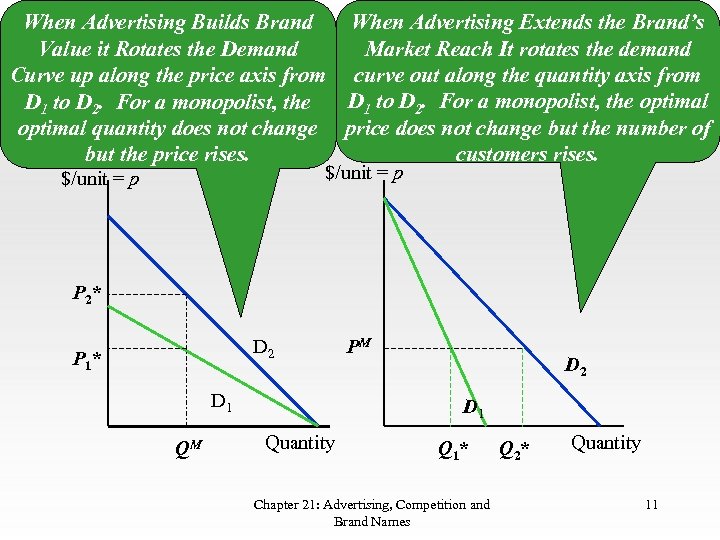

When Advertising Extends the Brand’s When Advertising Builds Brand Market Reach It rotates the demand Value it Rotates the Demand Curve up along the price axis from. Extending Reach (cont. ) from Building Value vs curve out along the quantity axis D 1 to D 2. For a monopolist, the optimal quantity does not change price does not change but the number of customers rises. but the price rises. $/unit = p P 2 * D 2 P 1 * D 1 QM PM D 2 D 1 Quantity Q 1 * Chapter 21: Advertising, Competition and Brand Names Q 2 * Quantity 11

Building Value vs Extending Reach (cont. ) • The evaluation of advertising efforts from a social welfare or efficiency point of view requires that we understand whether advertising predominantly builds value or extends market reach • This is even more true when we add in some competition. – When there is more than one firm and advertising extends market reach advertising may well be excessive • Now advertising works by stealing customers from rivals • Much greater possibility that game is like the wasteful advertising game described at start of chapter – When advertising works to build value, excessive advertising is less likely because advertising now works to permit charging existing customers a higher price— not by taking customers from rivals. Chapter 21: Advertising, Competition and Brand Names 12

Building Value vs Extending Reach (cont. ) • Amount of advertising is also likely to depend critically on nature of price competition and number of firms – When price competition is naturally fierce, firms may advertise a lot to differentiate their product and soften price competition – When the number of firms is small, firms may again advertise more because most of the gains of a firm’s advertising flow to that firm itself and not to its rivals – Note the potential interaction of these two effects. • Since advertising is largely a sunk cost, the need to do a lot of advertising to soften price competition may limit the equilibrium number of firms • As number of firms falls, each one is induced to advertise more • Advertising/sales ratio may be high in concentrated industries but again causality is not from advertising to concentration • Rea. Lemmon Case Chapter 21: Advertising, Competition and Brand Names 13

Cooperative Advertising • In contrast to analysis so far, much advertising and promotion is done by retailer on manufacturer’s behalf • Manufacturer and retailer may therefore wish to act cooperatively so as to avoid problems of underprovision of services discussed in Chapter 18 – Retailer may try to free ride on promotional efforts of other retailers – Retailer may substitute less-costly brands for manufacturer’s product • These cooperative arrangements take a variety of forms such as slotting fees, “pay-to-stay” fees, and failure fees • However, they all result in the manufacturer paying part of the retailer’s promotional expense Chapter 21: Advertising, Competition and Brand Names 14

Cooperative Advertising (cont. ) • Because cooperative advertising contracts can resolve many of the manufacturer/retailer conflicts they have the potential to promote economic welfare. • But, cooperative advertising can also be used to suppress or weaken competition – Mc. Cormick Spice company may have used slotting fees to buy shelf space preemptively and foreclose it to rival spice firms – Slotting and promotional fees can be offered on different terms to retailers (price discrimination) • usually large retailers will get a quantity discount • Large retailers (Wal. Mart, Borders) then gain competitive advantage over small ones (independent retailers and bookstores) – Slotting fees may be paid to retailer in return for keeping retail price high (Resale Price Maintenace) Chapter 21: Advertising, Competition and Brand Names 15

3eec7efd41332237d99fa7c3f1a2c53d.ppt