01a7d87101bdda97ae539154928f58a3.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 115

Abscisic Acid: A Seed Maturation and Antistress Signal

Contents Occurrence, Chemical Structure, and Measurement of ABA Biosynthesis, Metabolism, and Transport of ABA Developmental and Physiological Effect of ABA

Abscisic Acid (ABA) Physiologists suspected that the phenomena of seed & bud dormancy were caused by inhibitory compounds. The experiments led to the identification of a group of growthinhibiting compounds, including dormin

Upon discovery that dormin was chemically identical to a substance that promotes the abscission of cotton fruits, abscissin II The compound was renamed abscisic acid (ABA)

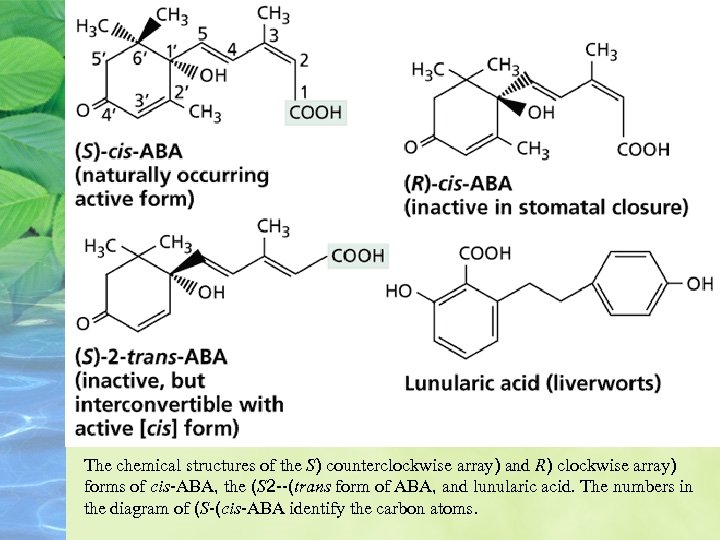

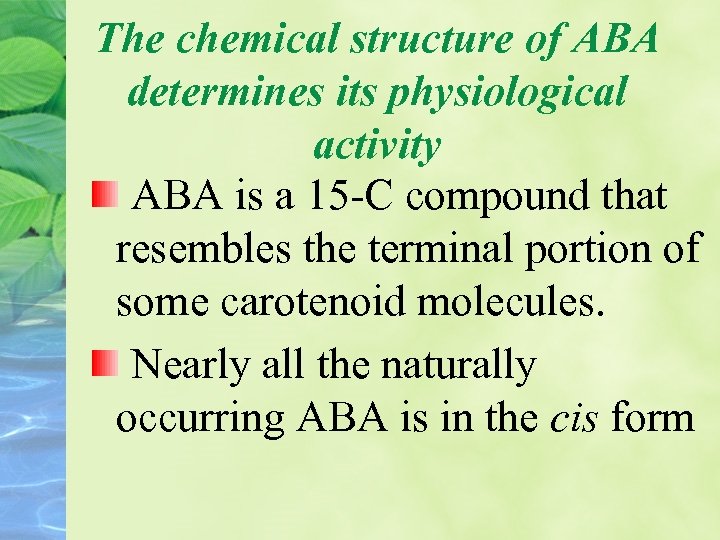

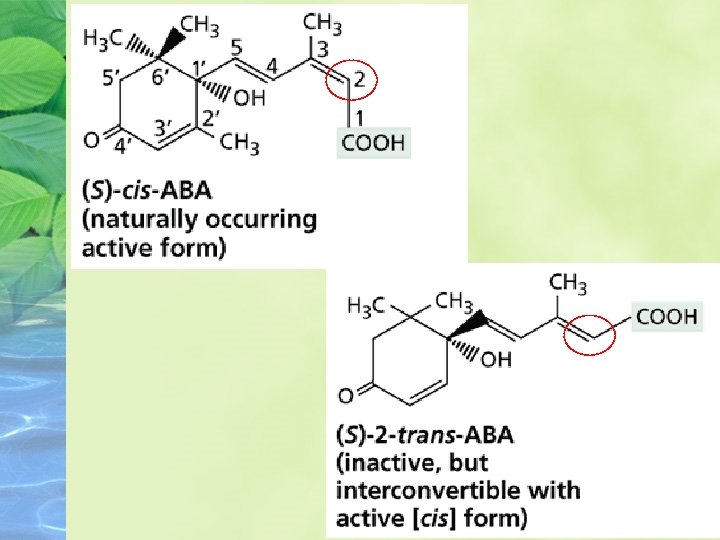

The chemical structures of the S) counterclockwise array) and R) clockwise array) forms of cis-ABA, the (S 2 --(trans form of ABA, and lunularic acid. The numbers in the diagram of (S-(cis-ABA identify the carbon atoms.

Occurrence, Chemical Structure, and Measurement of ABA is a ubiquitous plant hormone in vascular plants.

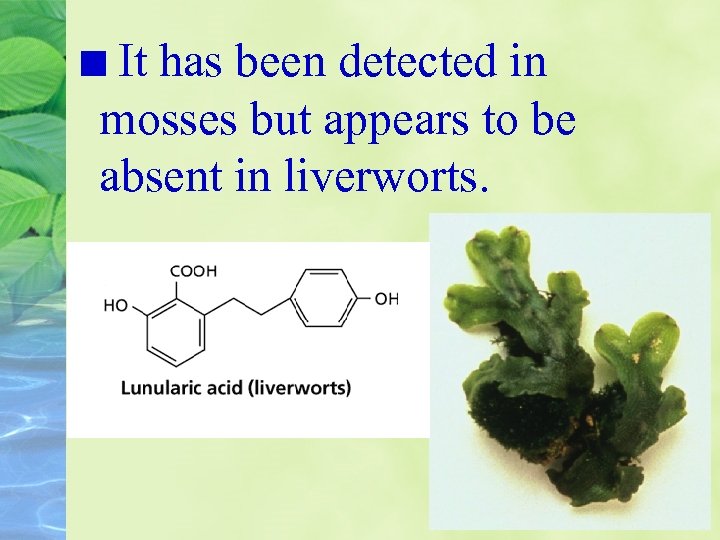

It has been detected in mosses but appears to be absent in liverworts.

ABA has been detected in living tissues from the root cap to the apical bud. It is synthesized in almost all cells that contain chloroplasts or amyloplasts.

Chloroplasts in Leaf Cells Potato Amyloplasts

The chemical structure of ABA determines its physiological activity ABA is a 15 -C compound that resembles the terminal portion of some carotenoid molecules. Nearly all the naturally occurring ABA is in the cis form

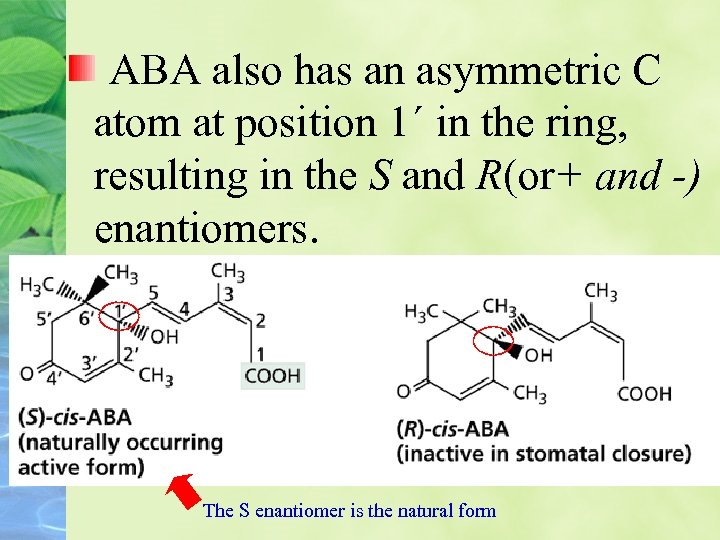

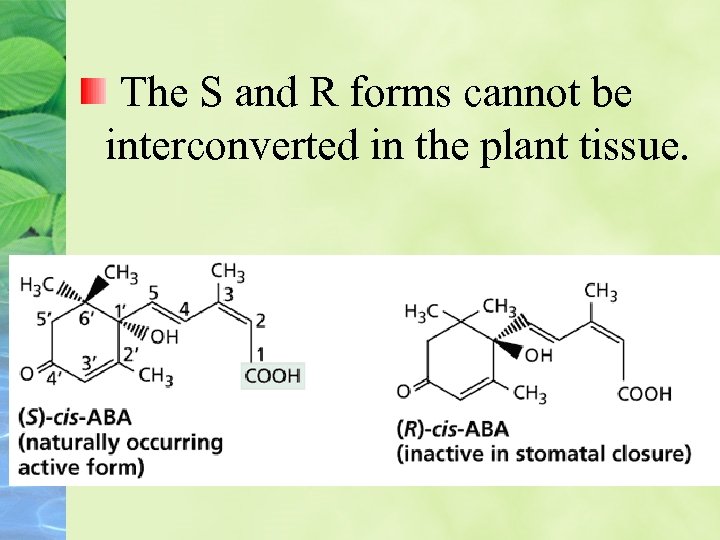

ABA also has an asymmetric C atom at position 1´ in the ring, resulting in the S and R(or+ and -) enantiomers. The S enantiomer is the natural form

The S and R forms cannot be interconverted in the plant tissue.

ABA is assayed by biological, physical, and chemical methods Avariety of bioassays have been used for ABA inhibition of coleoptile growth germination GA-induced α-amylase synthesis

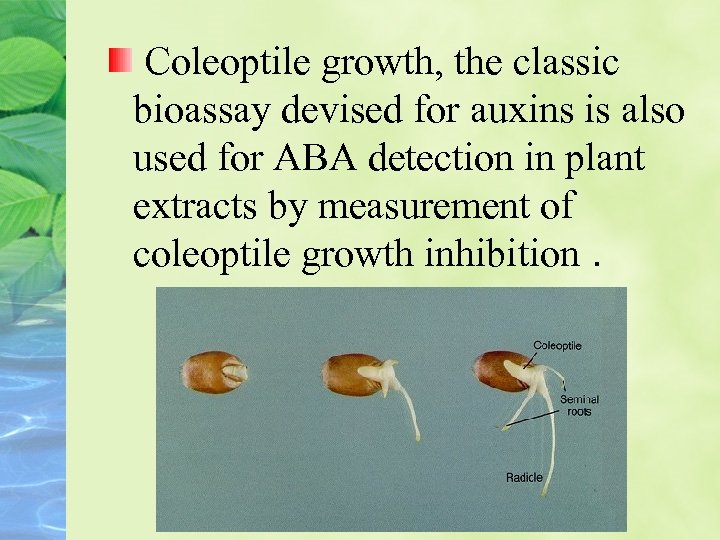

Coleoptile growth, the classic bioassay devised for auxins is also used for ABA detection in plant extracts by measurement of coleoptile growth inhibition.

This bioassay has adequate sensitivity (minimum detectable level is 10– 7 M) and shows a linear response in the range of 10– 7 to 10– 5 M, but it has some disadvantages.

Physical methods of detection are much more reliable than bioassay. The most widely used techniques are those based on gas chromatography or HPLC.

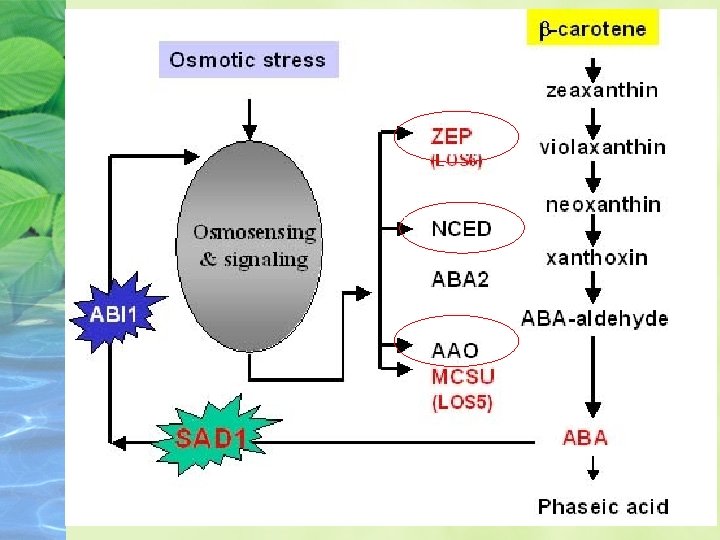

Biosynthesis, Metabolism, and Transport of ABA is synthesized from a carotenoid intermediate Biosynthesis takes place in chloroplasts and other plastids.

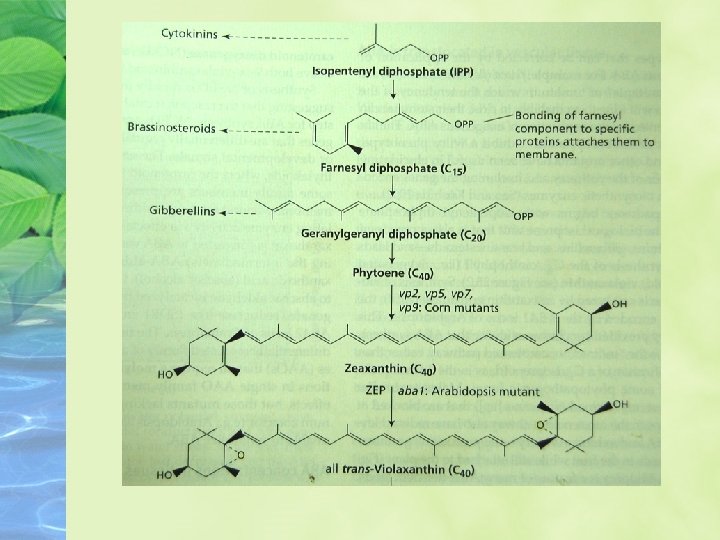

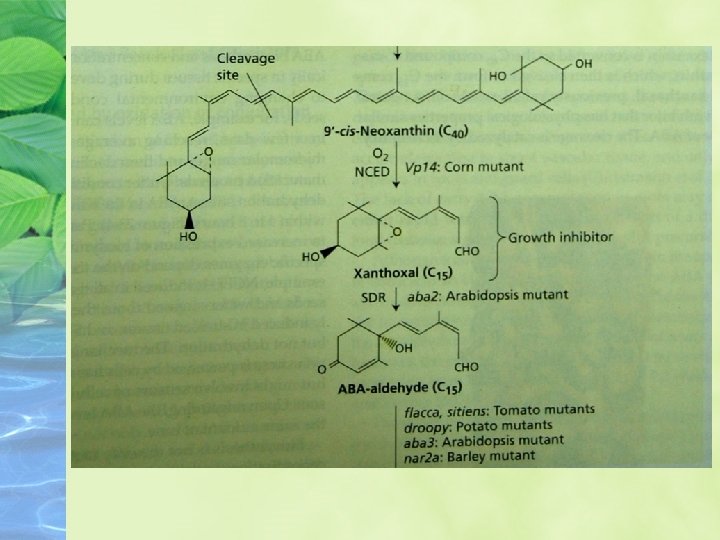

The pathway begins with isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and leads to the synthesis of the C 40 xanthophyll violaxanthin.

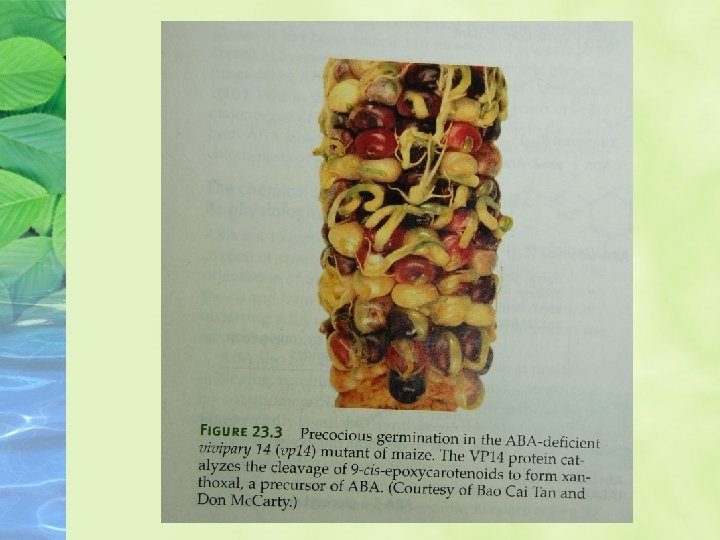

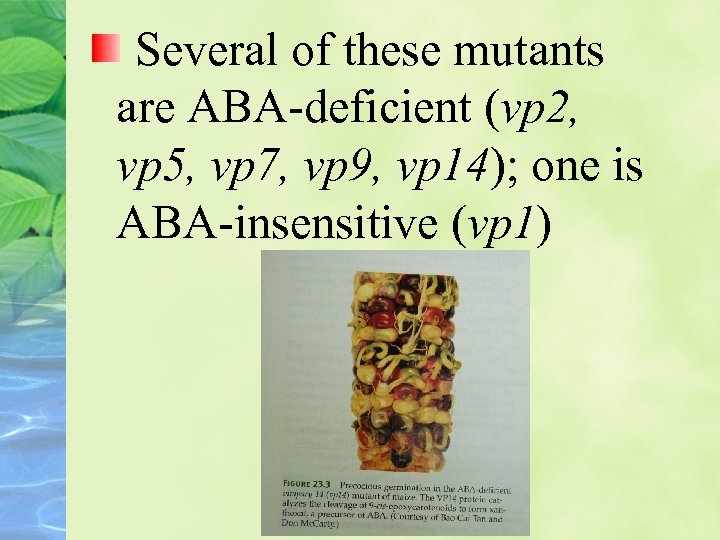

Maize mutants (viviparous; vp) that are blocked at other steps in the carotenoid pathway also have reduced levels of ABA and exhibit vivipary.

Synthesis of NCED is rapidly induced by water stress.

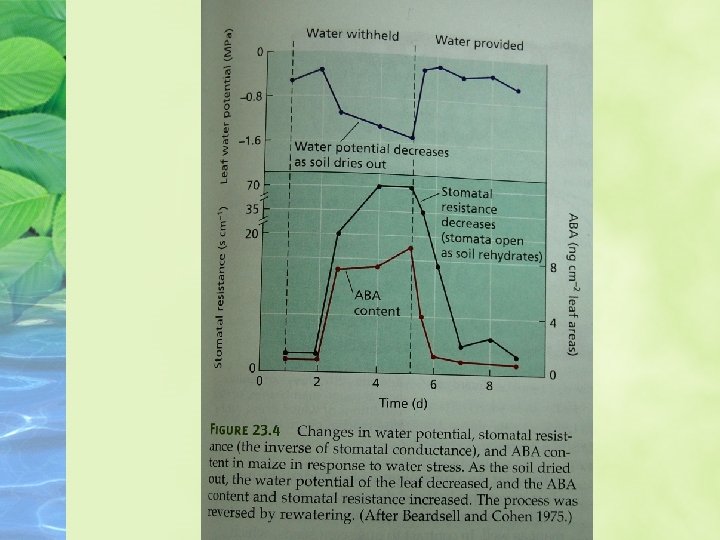

ABA concentrations in tissues are highly variable ABA biosynthesis and concentrations can fluctuate dramatically in specific tissues during development or in response to changing environmental conditions. of ABA and exhibit vivipary.

Part of this increase is due to increased expression of biosynthetic enzymes, but the specific enzymes depend on the tissue and the signal.

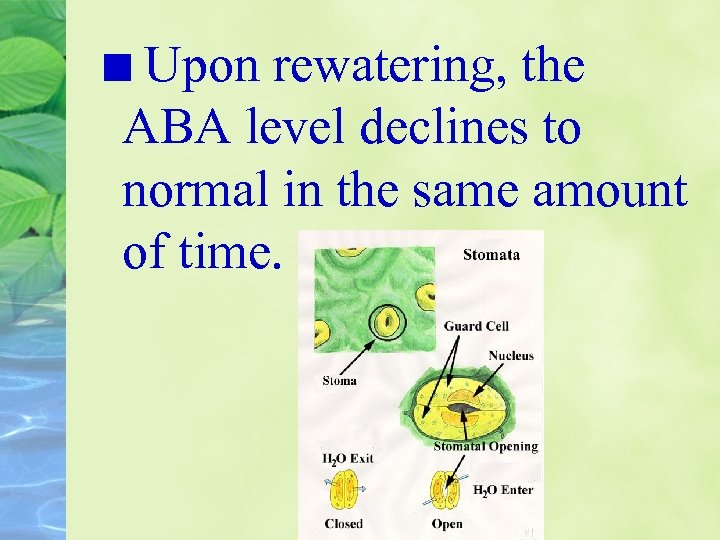

Upon rewatering, the ABA level declines to normal in the same amount of time.

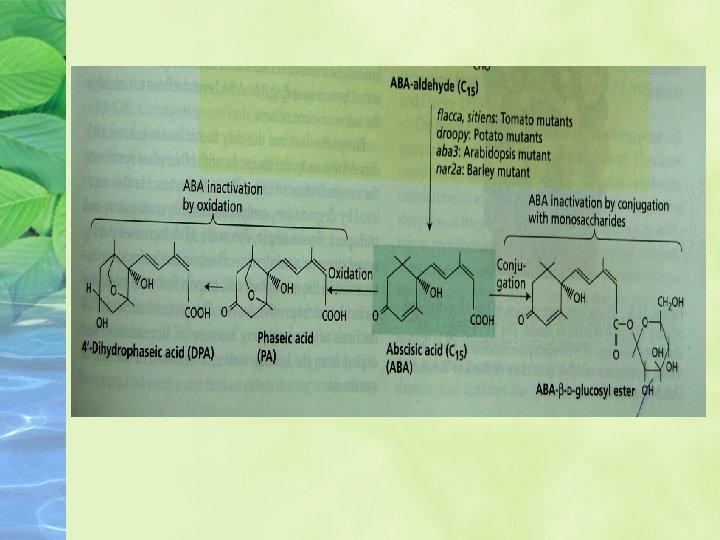

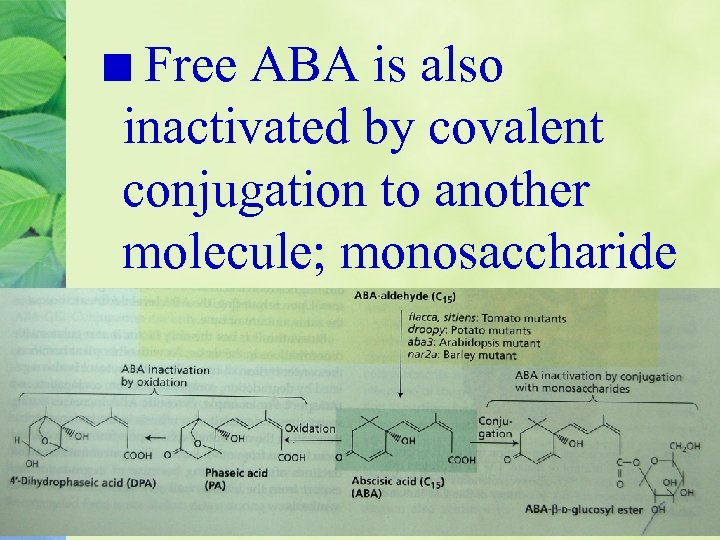

ABA can be inactivated by oxidation or conjugation A major cause of the inactivation of free ABA is oxidation

Free ABA is also inactivated by covalent conjugation to another molecule; monosaccharide

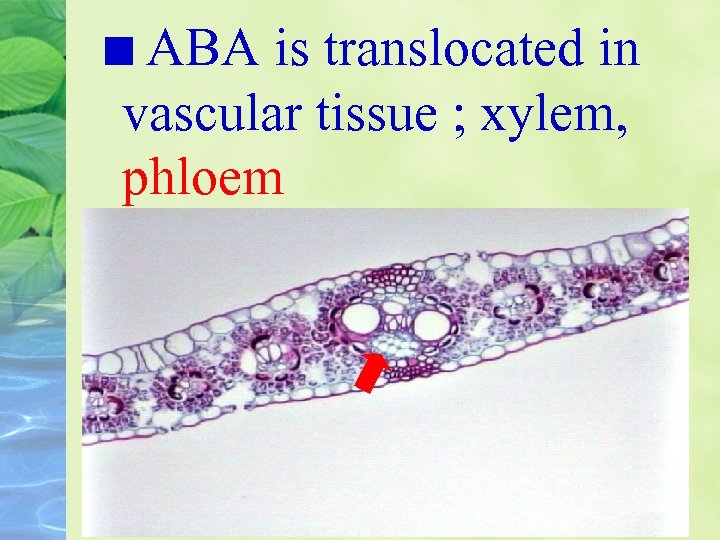

ABA is translocated in vascular tissue ; xylem, phloem

As water stress begins, some of the ABA carried by the xylem stream may be synthesized in roots that are indirect contract with the drying soil.

The lack of early ABA accumulation in roots may reflect either rapid transport of ABA or transport of a distinct long-distrance signal, possible even an ABA precursor.

Although a concentration of 0. 3 μM ABA in the apoplast is sufficient to close stomata, not all of the ABA in the xylem stream reaches the guardcells.

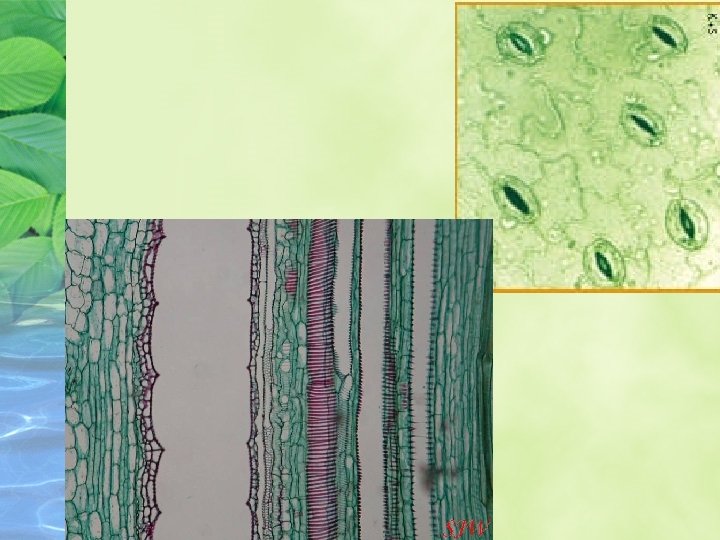

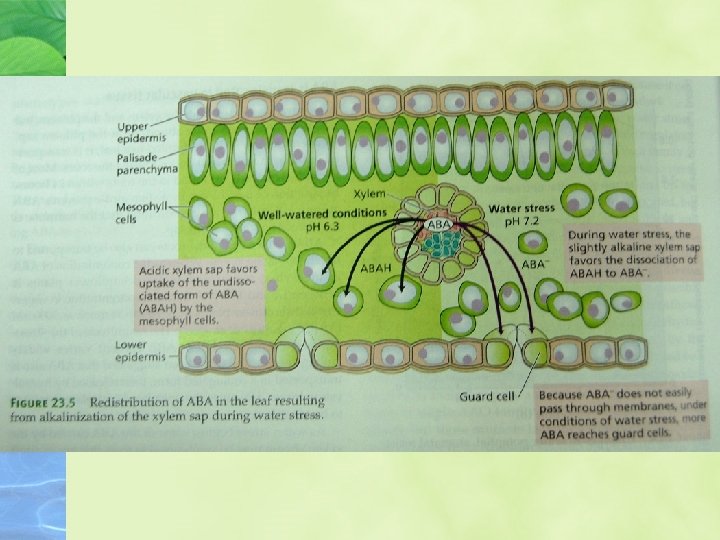

The major control of ABA distribution among plant cell compartments follows the “anion trap” concept.

The dissociated (anion) form this weak acid accumulates in alkaline compartments and may be redistributed according to the steepness of the p. H gradients across membranes.

Stress-induced alkalinization of the apoplast favors formation of the dissociated form of -, which abscisic acid, ABA does not readily cross membranes.

That ABA is redistributed in the leaf in this way without any increase in the total ABA level. Therefore, the increas in xylem sap p. H may function as a root signal that promotes early closure of the stomata.

Developmental and Physiological Effects of ABA plays primary regulatory roles in the initiation and maintenance of seed and bud dormancy and in plant’s response to stress.

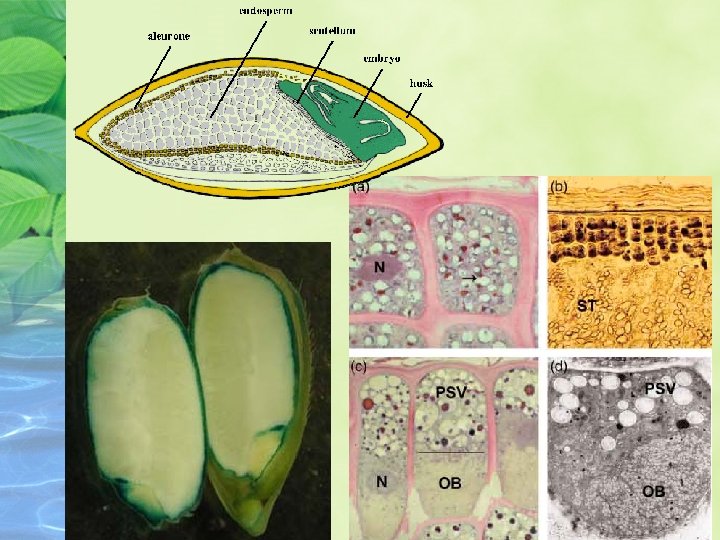

ABA regulates seed maturation Seed can be divided into three phases of approximately equal duration:

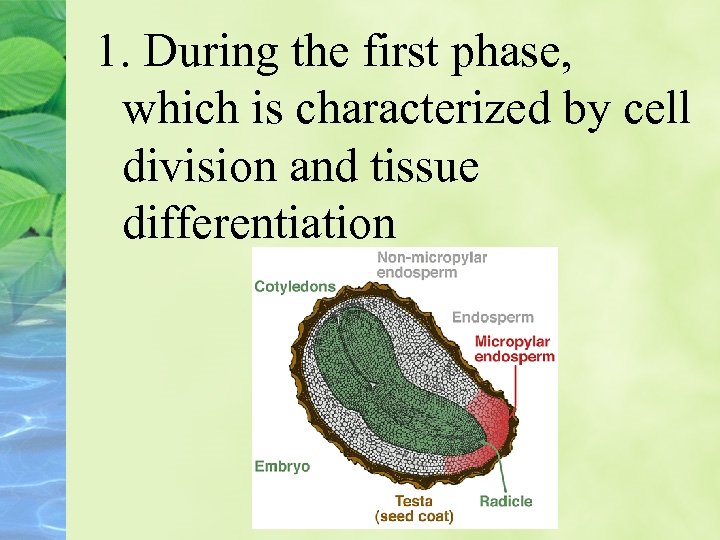

1. During the first phase, which is characterized by cell division and tissue differentiation

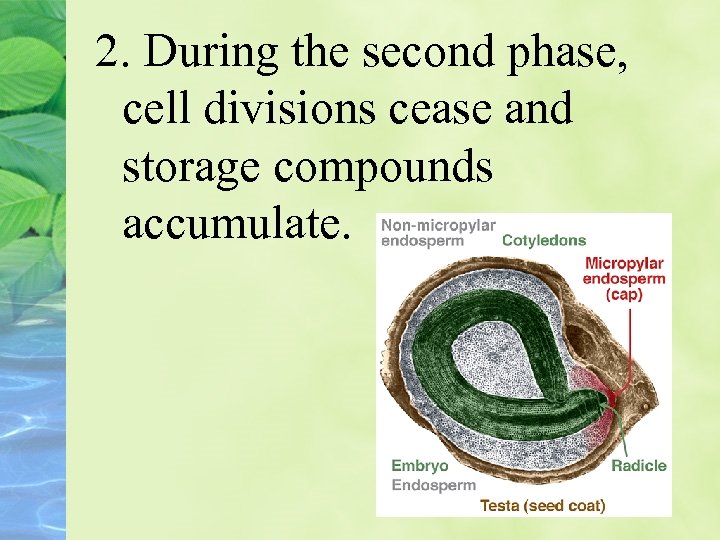

2. During the second phase, cell divisions cease and storage compounds accumulate.

3. During the final phase, the embryo becomes tolerant to dessication, and the seed dehydrates, losing up to 90% of it water.

As a consequence of dehydration, metabolism comes to a halt and enters a quiescent (resting) state.

The latter two phases result in the production of viable seeds with adequate resources to support germination and the capacity to wait weeks to years before resuming growth.

ABA inhibits precocious germination and vivipary ABA added to the culture medium inhibits precocious germination.

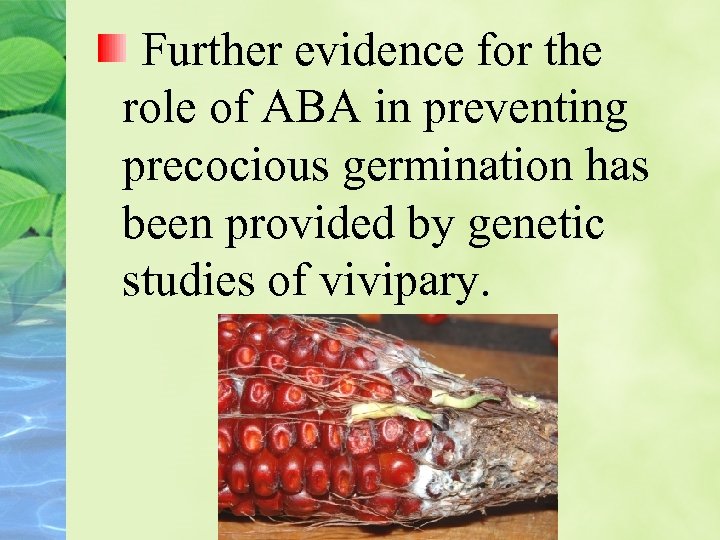

Further evidence for the role of ABA in preventing precocious germination has been provided by genetic studies of vivipary.

In maize, several viviparous mutants have been selected in which the embryos germinate directly on the cob while still attached plant.

Several of these mutants are ABA-deficient (vp 2, vp 5, vp 7, vp 9, vp 14); one is ABA-insensitive (vp 1)

ABA promotes seed storage reserve accumulation and desiccation tolerance During mid – to late embryogenesis, when seed ABA levels are highest, seeds accumulate storage compounds that will support seedling growth at germination.

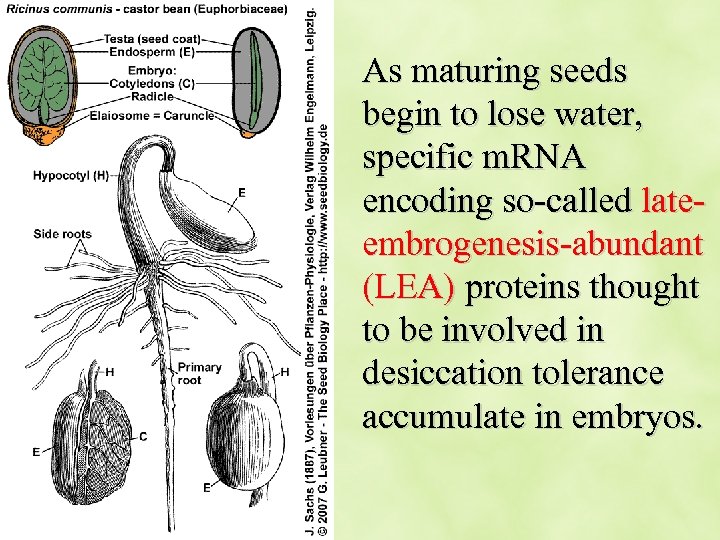

As maturing seeds begin to lose water, specific m. RNA encoding so-called lateembrogenesis-abundant (LEA) proteins thought to be involved in desiccation tolerance accumulate in embryos.

ABA not only regulates the accumulation of storage proteins and desiccation protectants during embryogenesis It can also maintain the mature embryo in a dormant state until environment are optimum for growth.

The seed coat or the embryo can cause dormancy During seed maturation, the embryo enters a quiescent phase in response to desiccation. Seed germination can be defined as the resumption of growth of the embryo of the mature seed.

In many cases a viable seed will not germinate even if all the necessary environmental conditions for growth are satisfied. This phenomenon is termed seed dormancy.

COAT-IMPOSED DORMANCY There are five basic mechanisms of coat-imposed dormancy. 1. Prevention of water uptake. 2. Mechanical conatraint. 3. Interference with gas exchange. 4. Retention of inhibitors. 5. Inhibitor production.

EMBRYO DORMANCY A dormancy that is intrinsic to the embryo and is not due to any influence of the seed coat or other surrounding tissues. In some cases, embryo dormancy can be relieved by amputation of the cotyledons

Embryo dormancy is thought to be due to the presence of inhibitors, especially ABA, as well as the absence of growth promoters, such as GA.

PRIMARY VERSUS SECONDARY SEED DORMANCY Different types of seed dormancy also can be distinguished on the basis of the timing of dormancy onset rather than the cause of dormancy.

Seeds that are released from the plant in a dormant state are said to exhibit primary dormancy. Seeds that are released from the plant in a nondormant state, but that become dormant if the conditions for germination are unfavorable, exhibit secondary dormancy.

Environmental factors control the release from seed dormancy 1. Afterripening 2. Chilling 3. Light

Seed dormancy is controlled by the ratio of ABA to GA ABA mutants have been useful in demonstrating the role of ABA in seed primary dormancy.

Dormancy of Arabidopsis seeds can be overcome with period of afterripening and/ or cold treatment. ABA-deficient (aba) mutants of Arabidopsis have been shown to be nondormant at maturity.

An elegant demonstration of the importance of the ratio of ABA to GA in seeds was provided by the genetic screen that led to isolation of the first ABAdeficient mutant of Arabidopsis.

Revertants were isolated, and they turned out to be mutants of abscisic acid synthesis. The revertants germinated because dormancy had not been induced.

ABA inhibits GA-induced enzyme production ABA inhibits the GA-induced synthesis of hydrolytic enzymes that are essential for the breakdown of storage reserves in germinating seeds.

ABA exerts this inhibitory effect via at least two mechanisms one direct and indirect: 1. VP 1, a protein originally identified as an activator of ABA-induced gene expression, acts as a transcriptional repressor of some GA-regulated genes. 2. ABA repression the GA-induced expression of GAMYB, a transcription factor that mediates the GA induction of α-amylase expression.

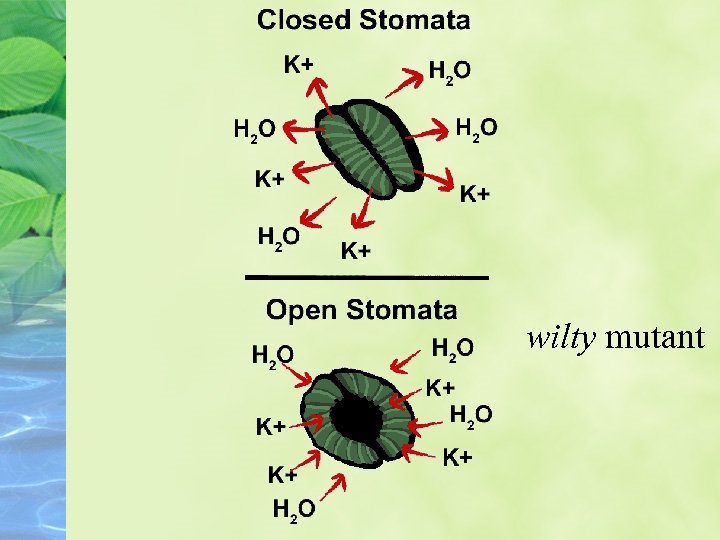

ABA closes stomata in response to water stress Elucidation of the roles of ABA in freezing, salt, and water stress led to the characterization of ABA as a stress hormone.

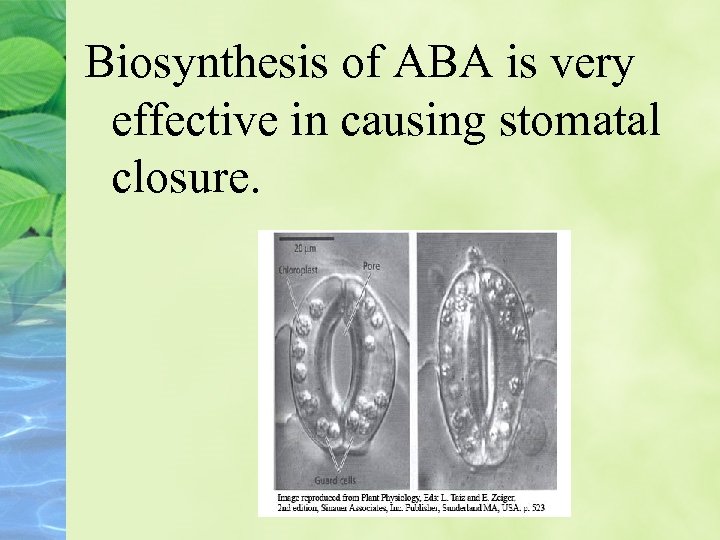

Biosynthesis of ABA is very effective in causing stomatal closure.

wilty mutant

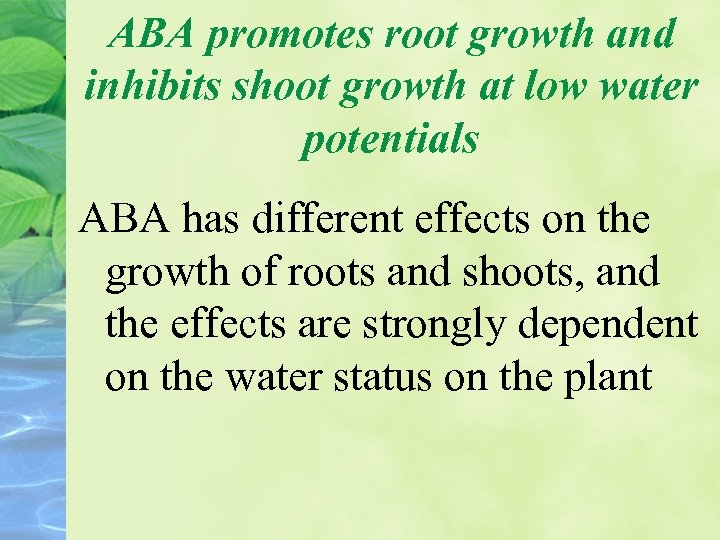

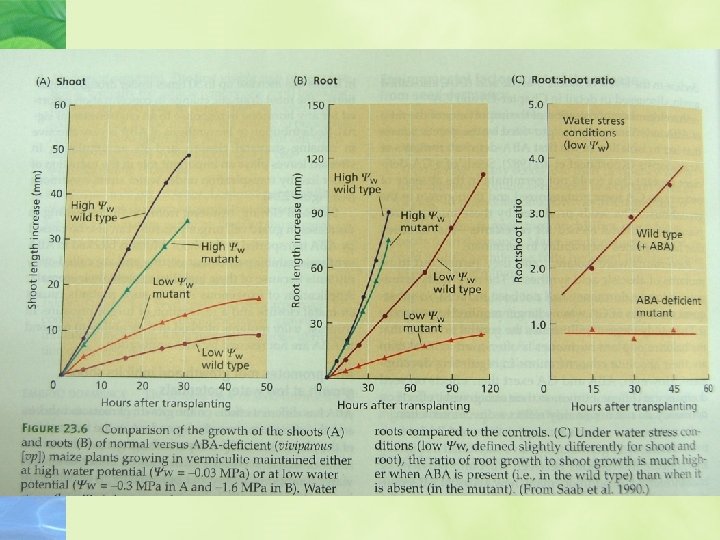

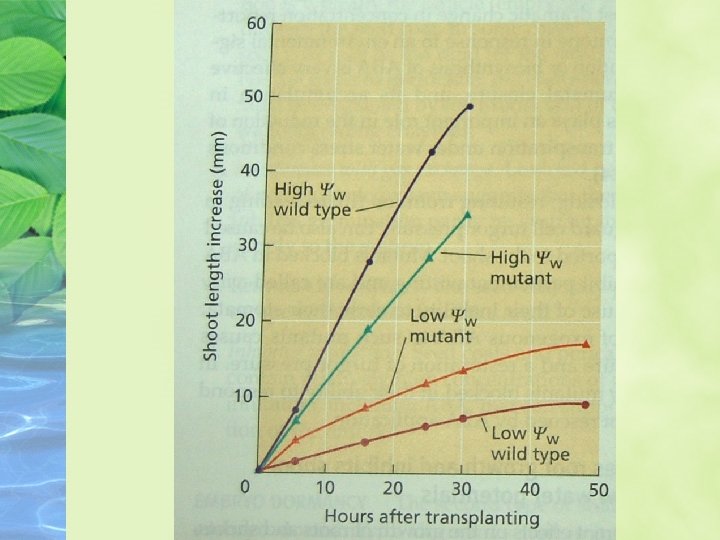

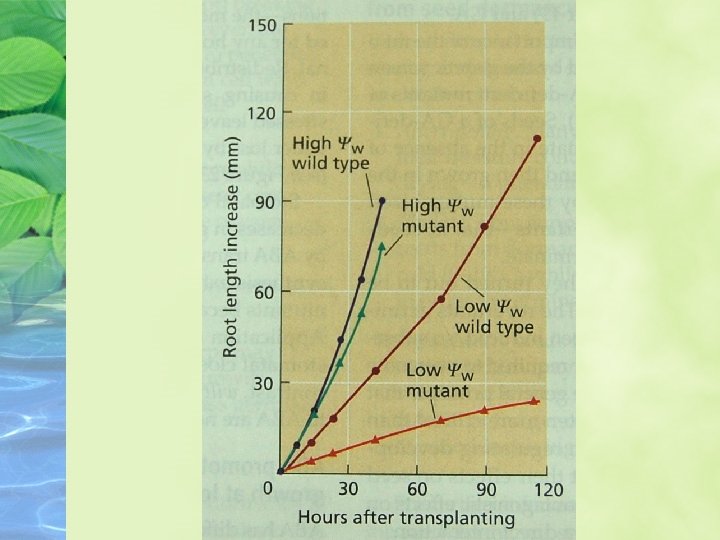

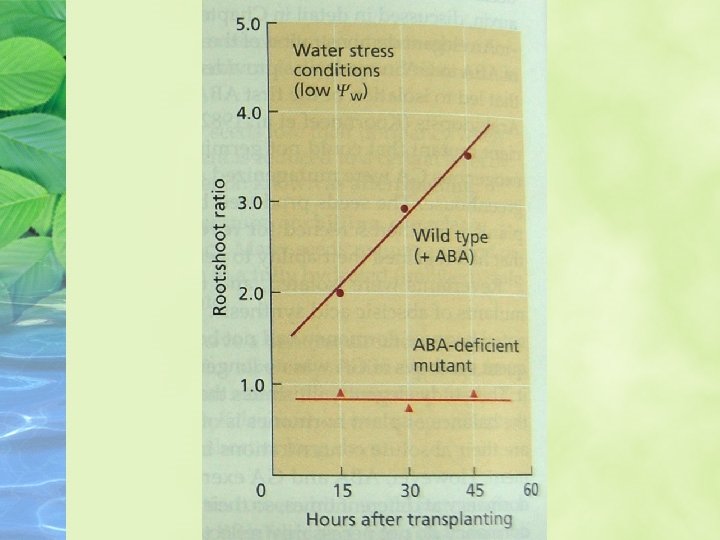

ABA promotes root growth and inhibits shoot growth at low water potentials ABA has different effects on the growth of roots and shoots, and the effects are strongly dependent on the water status on the plant

ABA promotes leaf senescence independently of ethylene ABA is clearly involved in leaf senescence, and through its promotion of senescence it might indirectly increase ethylene formation and stimulate abscission.

Leaf segments senesce faster in darkness than in light, and turn yellow as a result of chlorophyll breakdown.

ABA greatly accelerates the senescence of both leaf segments and attached leaves.

ABA accumulates in dormant buds ABA was originally suggested as the dormancy-inducing hormone because it accumulates in dormant buds and decrease after tissue exposed to low temperatures.

Later studies showed that the ABA content of buds does not always correlate with degree of dormancy.

Although much progress has been achieved in elucidating the role of ABA in seed dormancy by the use of ABA-deficient mutants, progress on the role of ABA in bud dormancy has lagged because of the lack of a convenient genetic system.

Analyses of traits such as dormancy are complicated by the fact that they are often controlled by the combined action of several genes, resulting in a gradation of phenotypes refereed to as quantitative traits.

ABA Signal Transduction Pathway

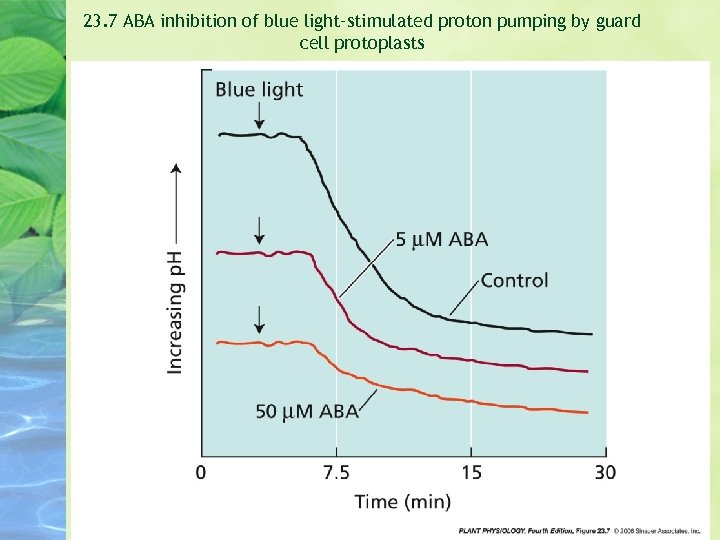

ABA regulates ion channels and the PM-ATPase in guard cell Stomatal close by the cell itself turgor pressure Triggered by two factors * ABA-induced plasma membrane depolarization * Increase [Ca 2+] in cytosol • Anathor factor contribute the depolrization is the • Plasma membrane H+-ATPase (PMATPase)

23. 7 ABA inhibition of blue light–stimulated proton pumping by guard cell protoplasts

![K+ channel is keep opening where plasma membrane is hyperpolarized Thus, [Ca 2+] and K+ channel is keep opening where plasma membrane is hyperpolarized Thus, [Ca 2+] and](https://present5.com/presentation/01a7d87101bdda97ae539154928f58a3/image-96.jpg)

K+ channel is keep opening where plasma membrane is hyperpolarized Thus, [Ca 2+] and p. H affect guard cell plasma membrane in two ways (1) Inhibiting inward of K+ channel and proton pump on plasma membrane (2) Activation the K+ efflux channel

ABA may be percesived by both cell surface intracellular receptor • Efforts to identify ABA receptors have employed both • biochemical and genetic approach

Three experiments support an intracellular location for the ABA receptor ABA supplied directly and continuously to the cytosol via a “patch pipette” inhibited both inward K+ channels and S-type anion channels, which are required for stomatal opening (Schwartz et al. 1994; schroeder et al. 2001)

Extracellar application of ABA was nearly twice as effective at inhibiting stomatal opening at p. H 6. 15, when it is fully protonated and readily taken up by guard cells, as it was at p. H 8, when it is largely dissociated to the anionic form that does not readily cross membranes(Anderson et al. 1994)

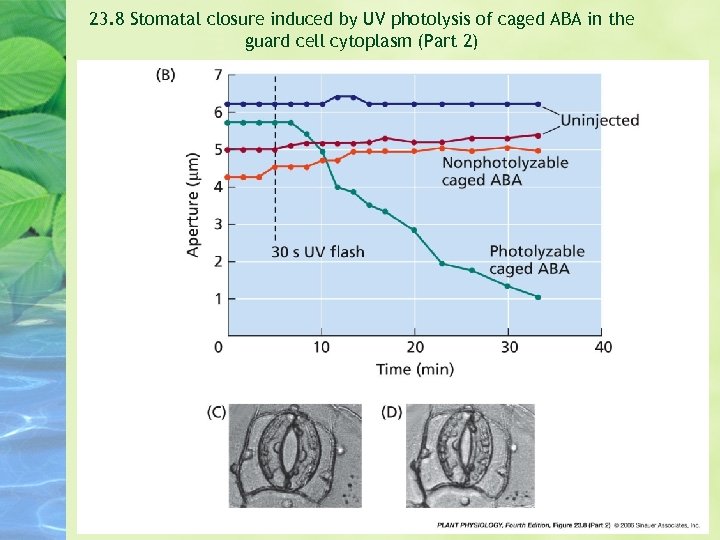

Microinjection of an inactive, “caged” form of ABA into guard cells of Commelina resulted in stomatal closure after the stomata were treated briefly with UV irradiation to activate the hormone --- that is, release it from its molecular cage. (Allen et al. 1994) Contral guard cells injected with a nonphotolyzable form of the caged ABA did not close after UV irrdiation.

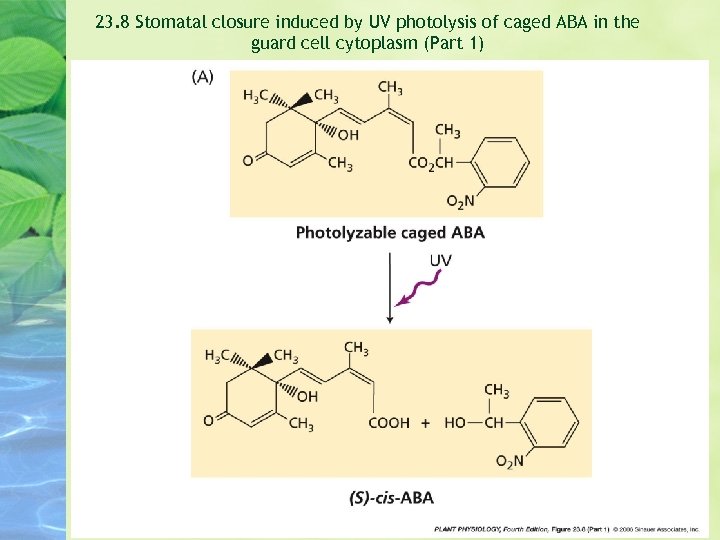

23. 8 Stomatal closure induced by UV photolysis of caged ABA in the guard cell cytoplasm (Part 1)

23. 8 Stomatal closure induced by UV photolysis of caged ABA in the guard cell cytoplasm (Part 2)

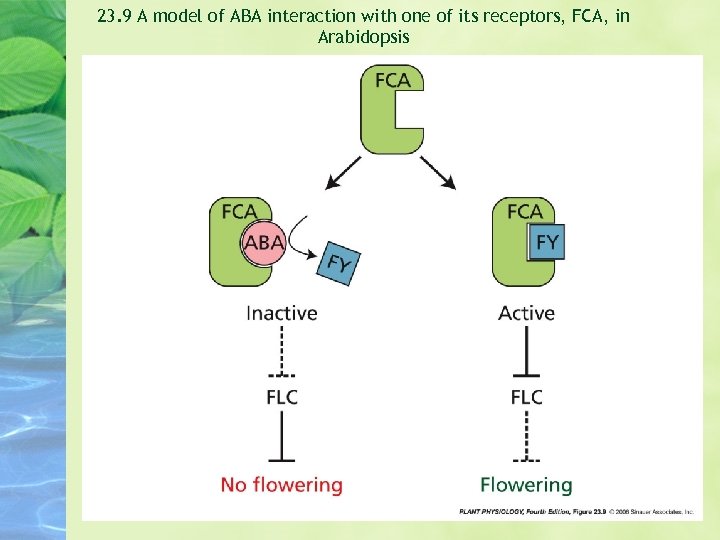

Determine the ABA-bind proteins with ABA itself or anti-idiotypic antibodies * Flowering Time Control Protein A (FCA) / ABA , Flowing Locus Y (FY) mechanism

23. 9 A model of ABA interaction with one of its receptors, FCA, in Arabidopsis

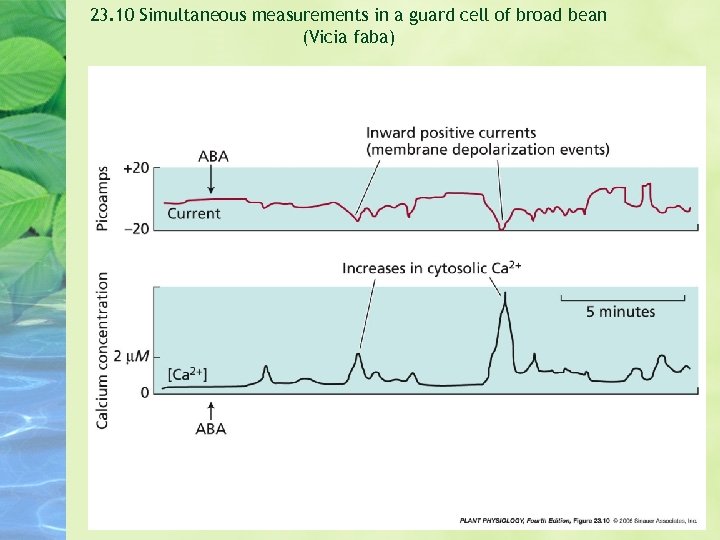

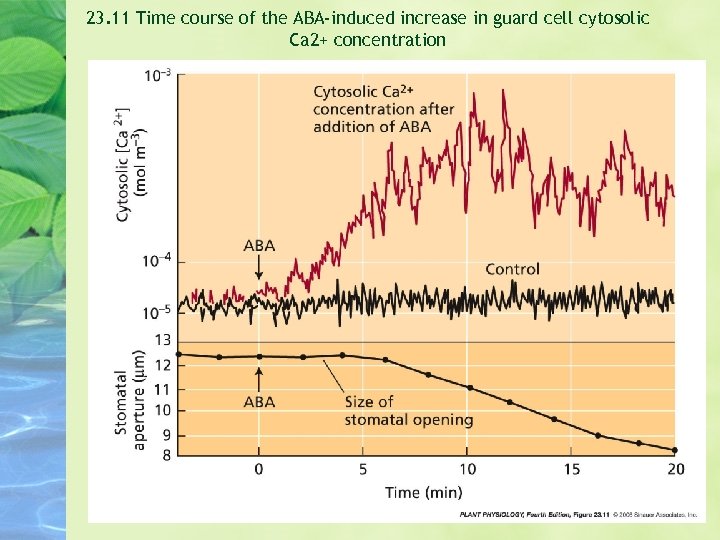

ABA signaling involves both calciumdependent and calcium-independent pathway ABA are transient membrane depolarization caused by the net influx of positive charge and transient increases in the cytosolic calcium concentration. ABA stimulates elevation in the concentration of cytosolic Ca 2+ by inducing both membrane channel and internal compartments, such as vacuole.

23. 10 Simultaneous measurements in a guard cell of broad bean (Vicia faba)

23. 11 Time course of the ABA-induced increase in guard cell cytosolic Ca 2+ concentration

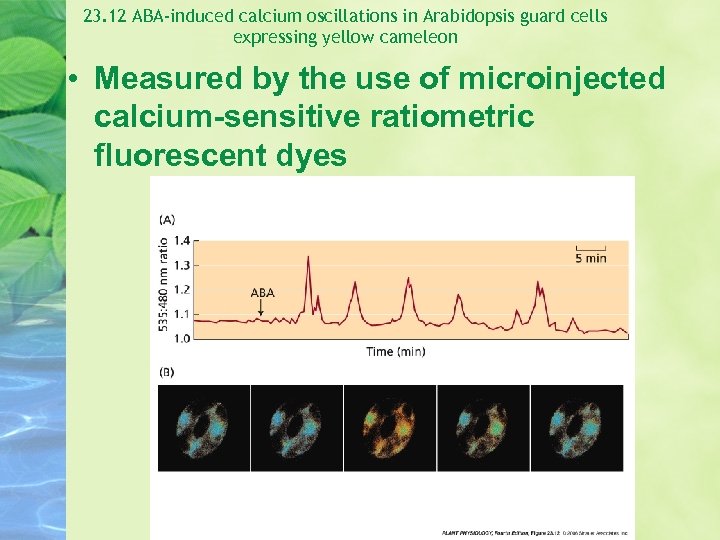

23. 12 ABA-induced calcium oscillations in Arabidopsis guard cells expressing yellow cameleon • Measured by the use of microinjected calcium-sensitive ratiometric fluorescent dyes

In addition to increasing the cytosolic calcium concentration, ABA caused an alkalinization of the cytosol from about p. H 7. 67 to p. H 7. 94. The increase in cytosolic p. H has been shown to increase the activity of the K+ efflux channels

ABA seems to be able to act via one or more calcium-independent pathways. A raise in cytosolic p. H can lead to the activation of outward K+ channels, and one effectof the abi 1 mutation is to render these K+ channels insensitive to p. H.

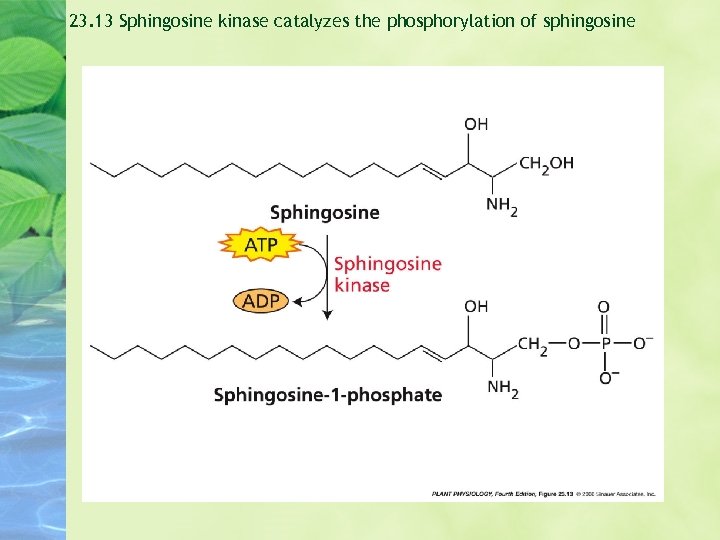

23. 13 Sphingosine kinase catalyzes the phosphorylation of sphingosine

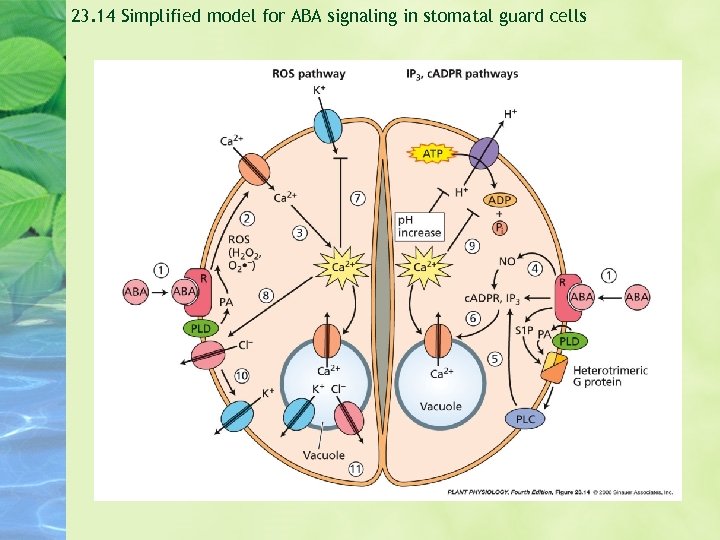

23. 14 Simplified model for ABA signaling in stomatal guard cells

ABA signaling involves ATP concentration Protein kinase inhibitors also block ABA-induced stomatal closing.

Other regulators also influence the ABA response Phosphatase, Gene Expression, Secondary messenger, Ethylene (so as other plant hormone), Stress, RNA regulator (such as mi. RNA) and so on.

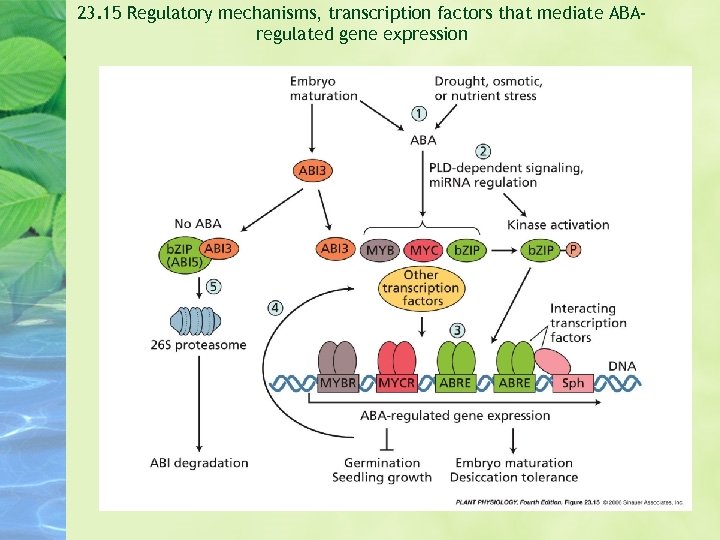

23. 15 Regulatory mechanisms, transcription factors that mediate ABAregulated gene expression

01a7d87101bdda97ae539154928f58a3.ppt