de5c8c1d29f3bda71a123eeca7df6c6e.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 22

A Privacy-Preserving Defense Mechanism Against Request Forgery Attacks Ben S. Y. Fung and Patrick P. C. Lee The Chinese University of Hong Kong Trust. Com’ 11 1

A Privacy-Preserving Defense Mechanism Against Request Forgery Attacks Ben S. Y. Fung and Patrick P. C. Lee The Chinese University of Hong Kong Trust. Com’ 11 1

Motivation Ø HTTP session state management is important in modern web applications • State includes authentication credentials • Clients insert state into HTTP requests • Web servers use state to identify clients’ privileges Ø Examples of state: • Cookies • Authentication header • Data embedded GET/PUT requests 2

Motivation Ø HTTP session state management is important in modern web applications • State includes authentication credentials • Clients insert state into HTTP requests • Web servers use state to identify clients’ privileges Ø Examples of state: • Cookies • Authentication header • Data embedded GET/PUT requests 2

Motivation Ø HTTP session state management is subject to various security risks Ø One top risk: Cross-site request forgery (CSRF) • An attacker triggers an HTTP request that carries session state of a client, without client’s knowledge • OWASP Top 10 Application Security Risks in 2010 3

Motivation Ø HTTP session state management is subject to various security risks Ø One top risk: Cross-site request forgery (CSRF) • An attacker triggers an HTTP request that carries session state of a client, without client’s knowledge • OWASP Top 10 Application Security Risks in 2010 3

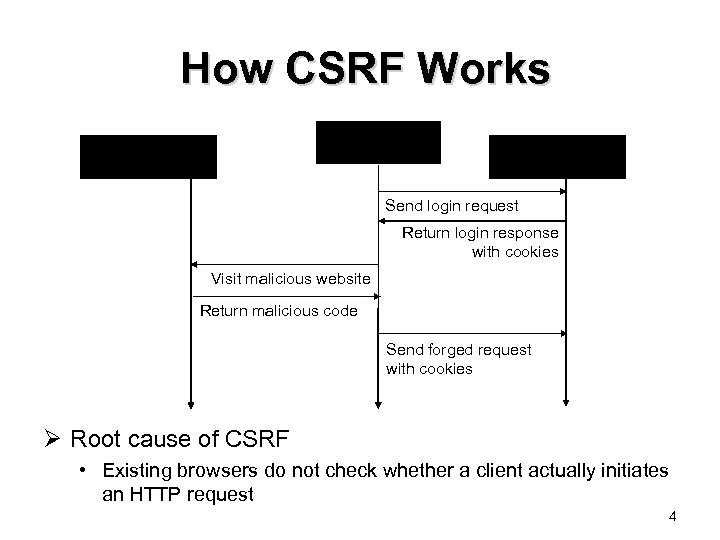

How CSRF Works Browser Malicious Website Target Website Send login request Return login response with cookies Visit malicious website Return malicious code Send forged request with cookies Ø Root cause of CSRF • Existing browsers do not check whether a client actually initiates an HTTP request 4

How CSRF Works Browser Malicious Website Target Website Send login request Return login response with cookies Visit malicious website Return malicious code Send forged request with cookies Ø Root cause of CSRF • Existing browsers do not check whether a client actually initiates an HTTP request 4

General Request Forgery Ø Variants of CSRF • Login CSRF [Barth et al. , 08] • Trigger forged login requests without active sessions • Clickjacking [Hansen and Grossman, 08] • Put an invisible frame of target website on malicious website Ø Same site request forgery (SSRF) • Target and malicious websites on same domain (origin) but maintained by different owners • http: //www. aaa. com/~alice • http: //www. aaa. com/~trudy • Cross-origin checking no longer works 5

General Request Forgery Ø Variants of CSRF • Login CSRF [Barth et al. , 08] • Trigger forged login requests without active sessions • Clickjacking [Hansen and Grossman, 08] • Put an invisible frame of target website on malicious website Ø Same site request forgery (SSRF) • Target and malicious websites on same domain (origin) but maintained by different owners • http: //www. aaa. com/~alice • http: //www. aaa. com/~trudy • Cross-origin checking no longer works 5

Related Work Ø Header checking • Checks origin header [Barth et al. , CCS 08]. Can’t defend SSRF Ø Token validation • Insert secure tokens in form [CSRFGuard, 10]. Token protected by same origin policy. Can’t defend SSRF. Ø Client-side defense • e. g. , BEAP [Mao et al. , FC 09] • Behavioral inference. Can generate high false alarms. 6

Related Work Ø Header checking • Checks origin header [Barth et al. , CCS 08]. Can’t defend SSRF Ø Token validation • Insert secure tokens in form [CSRFGuard, 10]. Token protected by same origin policy. Can’t defend SSRF. Ø Client-side defense • e. g. , BEAP [Mao et al. , FC 09] • Behavioral inference. Can generate high false alarms. 6

Related Work Ø Fine-grained access control • E. g. , SOMA [Oda et al. , CCS 08], Csfire [De Ryck et al. , ESSOS 10] • Servers configure access scopes where requests can be initiated. Browsers enforce access control • Can defend both CSRF and SSRF attacks • W 3 C drafts specs on fine-grained configuration Ø Limitation: • Access scope policies carry sensitive information Ø Question: Can we limit disclosure of sensitive information while allowing access control? 7

Related Work Ø Fine-grained access control • E. g. , SOMA [Oda et al. , CCS 08], Csfire [De Ryck et al. , ESSOS 10] • Servers configure access scopes where requests can be initiated. Browsers enforce access control • Can defend both CSRF and SSRF attacks • W 3 C drafts specs on fine-grained configuration Ø Limitation: • Access scope policies carry sensitive information Ø Question: Can we limit disclosure of sensitive information while allowing access control? 7

Our Work Ø Build De. Ref, a practical system that can defend different variants of CSRF and SSRF attacks Ø Enable fine-grained access configurations Ø Identify forged requests in privacy-preserving manner, without disclosing private information of both browser and website Ø Implement a proof-of-concept prototype atop Firefox and Word. Press feasible deployment 8

Our Work Ø Build De. Ref, a practical system that can defend different variants of CSRF and SSRF attacks Ø Enable fine-grained access configurations Ø Identify forged requests in privacy-preserving manner, without disclosing private information of both browser and website Ø Implement a proof-of-concept prototype atop Firefox and Word. Press feasible deployment 8

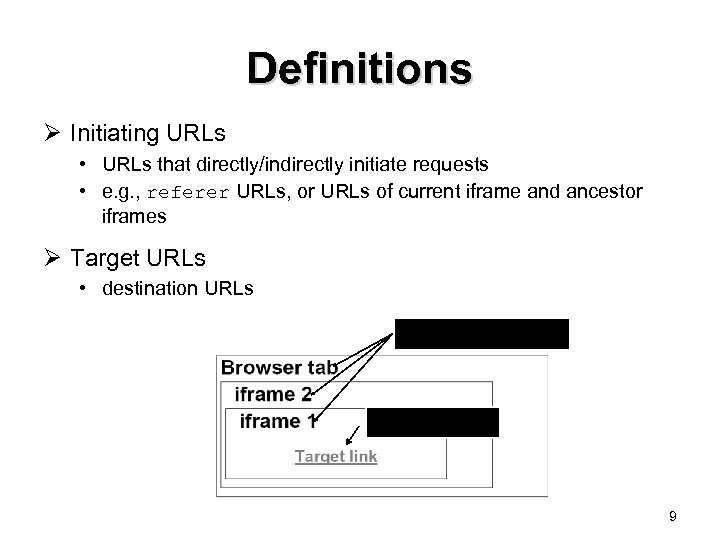

Definitions Ø Initiating URLs • URLs that directly/indirectly initiate requests • e. g. , referer URLs, or URLs of current iframe and ancestor iframes Ø Target URLs • destination URLs Initiating URLs Target URL 9

Definitions Ø Initiating URLs • URLs that directly/indirectly initiate requests • e. g. , referer URLs, or URLs of current iframe and ancestor iframes Ø Target URLs • destination URLs Initiating URLs Target URL 9

Threat Model Ø Websites can configure • target URLs to be protected • initiating URLs that are legitimate to send requests to protected target URLs Ø A request is forged if target URL is protected, but initiated URLs are not legitimate • Strip authentication credentials (including cookies and authentication headers) from forged requests Ø Aim to defend both CSRF and SSRF attacks 10

Threat Model Ø Websites can configure • target URLs to be protected • initiating URLs that are legitimate to send requests to protected target URLs Ø A request is forged if target URL is protected, but initiated URLs are not legitimate • Strip authentication credentials (including cookies and authentication headers) from forged requests Ø Aim to defend both CSRF and SSRF attacks 10

Fine-Grained Access Control in De. Ref Ø De. Ref is built on two access control lists (ACLs): • I-ACL: legitimate initiating URLs • T-ACL: protected target URLs Ø ACLs are configured with scopes • Based on scheme: //domain/path • e. g. , http: //. foo. com/dir Ø ACLs are transformed to “privacy-preserving” lists and stored in a policy file, which is publicized on website Ø De. Ref’s browser plugin checks scopes defined in the policy file, and caches recently checked scopes 11

Fine-Grained Access Control in De. Ref Ø De. Ref is built on two access control lists (ACLs): • I-ACL: legitimate initiating URLs • T-ACL: protected target URLs Ø ACLs are configured with scopes • Based on scheme: //domain/path • e. g. , http: //. foo. com/dir Ø ACLs are transformed to “privacy-preserving” lists and stored in a policy file, which is publicized on website Ø De. Ref’s browser plugin checks scopes defined in the policy file, and caches recently checked scopes 11

Privacy-Preserving Goals Ø Protect client’s private information • When browser checks if a URL is defined by a ACL, it does not reveal the URL to the website Ø Protect website’s private information • Browser does not know website’s configured scopes unless the scope matches the URL Ø De. Ref’s approach: two-phase checking • Hash checking: checks if a scope potentially matches ACLs • Blind checking: checks if a scope actually matches ACLs 12

Privacy-Preserving Goals Ø Protect client’s private information • When browser checks if a URL is defined by a ACL, it does not reveal the URL to the website Ø Protect website’s private information • Browser does not know website’s configured scopes unless the scope matches the URL Ø De. Ref’s approach: two-phase checking • Hash checking: checks if a scope potentially matches ACLs • Blind checking: checks if a scope actually matches ACLs 12

Hash Checking Ø Let • x 1 … x. L be a list of L configured scopes • s be a random salt • h(. ) be a k-bit one-way hash function Ø Website sends h(s, x 1), h(s, x 2), …, h(s, x. L) to browser 13

Hash Checking Ø Let • x 1 … x. L be a list of L configured scopes • s be a random salt • h(. ) be a k-bit one-way hash function Ø Website sends h(s, x 1), h(s, x 2), …, h(s, x. L) to browser 13

Hash Checking Ø To check if a URL y is defined in the configured scopes, we enumerate all possible scopes associated with y Ø For example, we have y = http: //abc. com/a. html Ø We need to check • • http: //. com/a. html http: //. com/ http: //abc. cm/a. html http: //abc. com/ 14

Hash Checking Ø To check if a URL y is defined in the configured scopes, we enumerate all possible scopes associated with y Ø For example, we have y = http: //abc. com/a. html Ø We need to check • • http: //. com/a. html http: //. com/ http: //abc. cm/a. html http: //abc. com/ 14

Hash Checking Ø Hash length k determines the degree of privacy of the website’s configured scope • Large k attacker more likely find configured scopes • e. g. , by offline dictionary attack with popular URLs • Small k have many false positives • e. g. , if k = 4, 1/24 = 1/16 of URLs in entire web will match Ø Good value of k • Filter out invalid scopes • Preserve the privacy of configured scopes Ø k is tunable depending on application needs 15

Hash Checking Ø Hash length k determines the degree of privacy of the website’s configured scope • Large k attacker more likely find configured scopes • e. g. , by offline dictionary attack with popular URLs • Small k have many false positives • e. g. , if k = 4, 1/24 = 1/16 of URLs in entire web will match Ø Good value of k • Filter out invalid scopes • Preserve the privacy of configured scopes Ø k is tunable depending on application needs 15

Blind Checking Ø Built on privacy-preserving matching protocol [R. Nojima et al. , Trans. on Data Privacy 09] • Based on Chaum’s RSA blind signature [Chaum, Crypto 83] Ø Idea (details in paper): • In bootstrap phase, website sends a list of signed hashes, which “hide” the configured scopes • Browser sends blinded hash for scope that passes hash checking • Website signs blinded hash and returns to browser • Browser unblinds signed hash and checks against a list of signed hashes 16

Blind Checking Ø Built on privacy-preserving matching protocol [R. Nojima et al. , Trans. on Data Privacy 09] • Based on Chaum’s RSA blind signature [Chaum, Crypto 83] Ø Idea (details in paper): • In bootstrap phase, website sends a list of signed hashes, which “hide” the configured scopes • Browser sends blinded hash for scope that passes hash checking • Website signs blinded hash and returns to browser • Browser unblinds signed hash and checks against a list of signed hashes 16

Two-Phase Privacy-Preserving Checking Ø Phase 1: hash checking • Filter out scopes that are not configured in ACLs • Reduce blind checking steps • Hash checking does not produce false negative Ø Phase 2: blind checking • Eliminate the false positives from hash checking 17

Two-Phase Privacy-Preserving Checking Ø Phase 1: hash checking • Filter out scopes that are not configured in ACLs • Reduce blind checking steps • Hash checking does not produce false negative Ø Phase 2: blind checking • Eliminate the false positives from hash checking 17

Implementation Ø Client-side: • Implement a Firefox plugin in Javascript • Intercepts HTTP/HTTPS messages • Enforces two-phase checking • Strips session information from forged requests Ø Server-side: • Implement a plugin in Word. Press 2. 0 in PHP Ø Backward compatible if only one side supports De. Ref allows incremental deployment 18

Implementation Ø Client-side: • Implement a Firefox plugin in Javascript • Intercepts HTTP/HTTPS messages • Enforces two-phase checking • Strips session information from forged requests Ø Server-side: • Implement a plugin in Word. Press 2. 0 in PHP Ø Backward compatible if only one side supports De. Ref allows incremental deployment 18

Evaluation Ø Goal: study response time overhead of De. Ref in real deployment compared to without De. Ref • Deploy three machines in a LAN: client (Firefox), target website (Word. Press), malicious website Ø Three scenarios: • #1: Browsing insensitive webpages (normal usage) • #2: Browsing sensitive webpages (e. g. , logins) • #3: Browsing malicious webpages that trigger CSRF attacks 19

Evaluation Ø Goal: study response time overhead of De. Ref in real deployment compared to without De. Ref • Deploy three machines in a LAN: client (Firefox), target website (Word. Press), malicious website Ø Three scenarios: • #1: Browsing insensitive webpages (normal usage) • #2: Browsing sensitive webpages (e. g. , logins) • #3: Browsing malicious webpages that trigger CSRF attacks 19

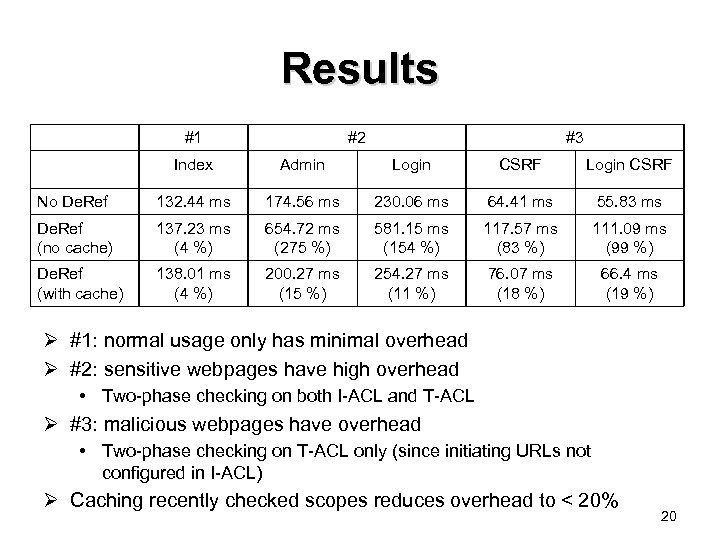

Results #1 #2 #3 Index Admin Login CSRF No De. Ref 132. 44 ms 174. 56 ms 230. 06 ms 64. 41 ms 55. 83 ms De. Ref (no cache) 137. 23 ms (4 %) 654. 72 ms (275 %) 581. 15 ms (154 %) 117. 57 ms (83 %) 111. 09 ms (99 %) De. Ref (with cache) 138. 01 ms (4 %) 200. 27 ms (15 %) 254. 27 ms (11 %) 76. 07 ms (18 %) 66. 4 ms (19 %) Ø #1: normal usage only has minimal overhead Ø #2: sensitive webpages have high overhead • Two-phase checking on both I-ACL and T-ACL Ø #3: malicious webpages have overhead • Two-phase checking on T-ACL only (since initiating URLs not configured in I-ACL) Ø Caching recently checked scopes reduces overhead to < 20% 20

Results #1 #2 #3 Index Admin Login CSRF No De. Ref 132. 44 ms 174. 56 ms 230. 06 ms 64. 41 ms 55. 83 ms De. Ref (no cache) 137. 23 ms (4 %) 654. 72 ms (275 %) 581. 15 ms (154 %) 117. 57 ms (83 %) 111. 09 ms (99 %) De. Ref (with cache) 138. 01 ms (4 %) 200. 27 ms (15 %) 254. 27 ms (11 %) 76. 07 ms (18 %) 66. 4 ms (19 %) Ø #1: normal usage only has minimal overhead Ø #2: sensitive webpages have high overhead • Two-phase checking on both I-ACL and T-ACL Ø #3: malicious webpages have overhead • Two-phase checking on T-ACL only (since initiating URLs not configured in I-ACL) Ø Caching recently checked scopes reduces overhead to < 20% 20

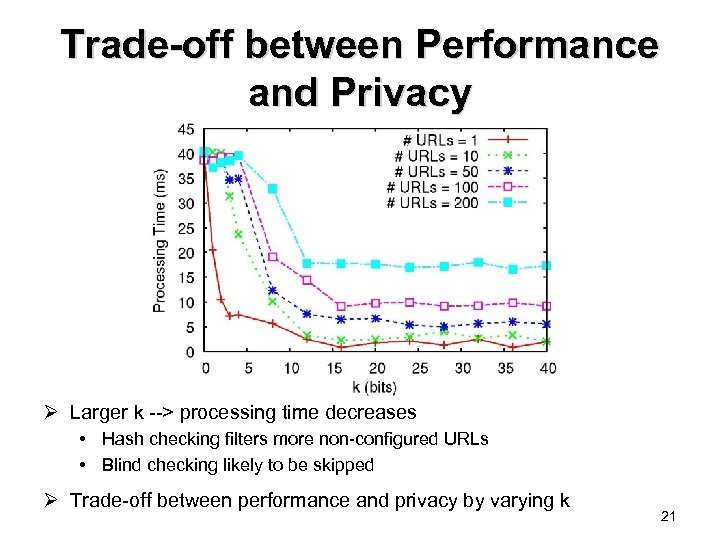

Trade-off between Performance and Privacy Ø Larger k --> processing time decreases • Hash checking filters more non-configured URLs • Blind checking likely to be skipped Ø Trade-off between performance and privacy by varying k 21

Trade-off between Performance and Privacy Ø Larger k --> processing time decreases • Hash checking filters more non-configured URLs • Blind checking likely to be skipped Ø Trade-off between performance and privacy by varying k 21

Conclusions Ø De. Ref: a practical system that defends a general class of request forgery attacks • Enable fine-grained access control in a privacypreserving manner • Use tunable two-phase checking to trade-off between performance privacy • Implement a proof-of-concept prototype atop Firefox and Word. Press Ø Source code: • http: //ansrlab. cse. cuhk. edu. hk/software/deref 22

Conclusions Ø De. Ref: a practical system that defends a general class of request forgery attacks • Enable fine-grained access control in a privacypreserving manner • Use tunable two-phase checking to trade-off between performance privacy • Implement a proof-of-concept prototype atop Firefox and Word. Press Ø Source code: • http: //ansrlab. cse. cuhk. edu. hk/software/deref 22