d3fefeb60f087f12f334fa7dc2f19f8a.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 66

8 IMPORT TARIFFS AND QUOTAS UNDER PERFECT COMPETITION 1 A Brief History of the World Trade Organization 2 The Gains from Trade 3 Import Tariffs for a Small Country 4 Import Tariffs for a Large Country 5 Import Quotas 6 Conclusions

8 IMPORT TARIFFS AND QUOTAS UNDER PERFECT COMPETITION 1 A Brief History of the World Trade Organization 2 The Gains from Trade 3 Import Tariffs for a Small Country 4 Import Tariffs for a Large Country 5 Import Quotas 6 Conclusions

Introduction • During the 2000 presidential campaign, President George W. Bush promised to consider implementing a tariff on the imports of steel. • This was a political move to secure votes in large steel-producing states as the tariffs would “protect” the domestic producers of steel. • The steel tariff is an example of a trade policy—a government action meant to influence the amount of international trade. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 2 of 136

Introduction • During the 2000 presidential campaign, President George W. Bush promised to consider implementing a tariff on the imports of steel. • This was a political move to secure votes in large steel-producing states as the tariffs would “protect” the domestic producers of steel. • The steel tariff is an example of a trade policy—a government action meant to influence the amount of international trade. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 2 of 136

Introduction • Because gains from trade are unevenly spread, producers often feel the government should help them limit losses due to competition from trade. • Trade policy can include the use of import tariffs (taxes on imports), import quotas (limits on imports), and subsidies for exports. • We will assume that firms are perfectly competitive. They produce a homogeneous good and are small compared to the market. w Firms are price takers © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 3 of 136

Introduction • Because gains from trade are unevenly spread, producers often feel the government should help them limit losses due to competition from trade. • Trade policy can include the use of import tariffs (taxes on imports), import quotas (limits on imports), and subsidies for exports. • We will assume that firms are perfectly competitive. They produce a homogeneous good and are small compared to the market. w Firms are price takers © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 3 of 136

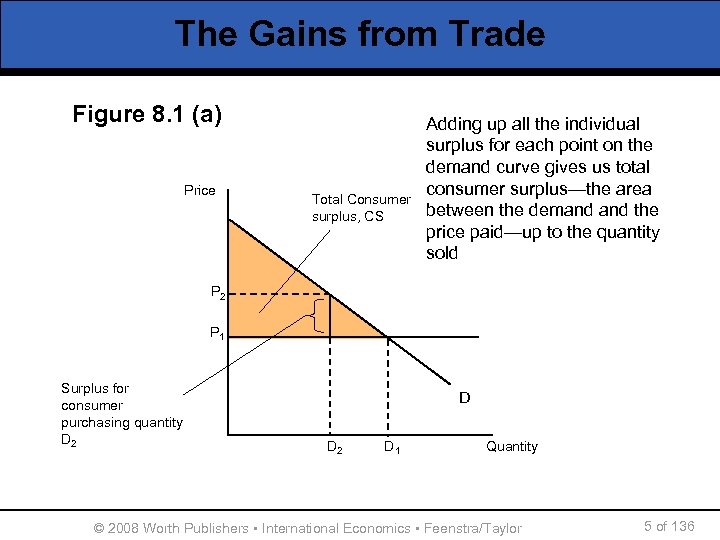

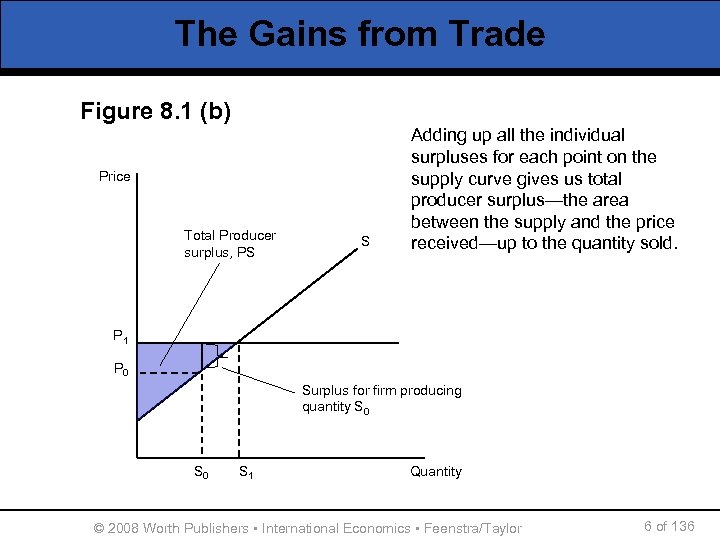

The Gains from Trade • We will now demonstrate the gains from trade using Home demand supply curves, together with the concepts of consumer surplus and producer surplus. • Consumer and Producer Surplus w Figure 8. 1 (a) shows the Home demand curve D where consumers face a price of P 1. w Remember, CS is the difference between the price the consumer is willing to pay and the actual price. w Part (b) of figure 8. 1 illustrates producer surplus. w Remember that PS is the difference between MC and price, where the supply curve represents a firm’s MC. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 4 of 136

The Gains from Trade • We will now demonstrate the gains from trade using Home demand supply curves, together with the concepts of consumer surplus and producer surplus. • Consumer and Producer Surplus w Figure 8. 1 (a) shows the Home demand curve D where consumers face a price of P 1. w Remember, CS is the difference between the price the consumer is willing to pay and the actual price. w Part (b) of figure 8. 1 illustrates producer surplus. w Remember that PS is the difference between MC and price, where the supply curve represents a firm’s MC. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 4 of 136

The Gains from Trade Figure 8. 1 (a) Price Total Consumer surplus, CS Adding up all curve gives us the The demand the individual surplus for each pointeach unit of consumer’s value for on the A consumer who purchases demand curve gives consumers the good. Given P 1, us total D 2 has a value of of but consumer total P 2, D 1. only has will buy a surplus—the area to pay P – that gives surplus between 1 the demand the equal to (P 2 -P to price paid—up 1) the quantity sold P 2 P 1 Surplus for consumer purchasing quantity D 2 D 1 Quantity © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 5 of 136

The Gains from Trade Figure 8. 1 (a) Price Total Consumer surplus, CS Adding up all curve gives us the The demand the individual surplus for each pointeach unit of consumer’s value for on the A consumer who purchases demand curve gives consumers the good. Given P 1, us total D 2 has a value of of but consumer total P 2, D 1. only has will buy a surplus—the area to pay P – that gives surplus between 1 the demand the equal to (P 2 -P to price paid—up 1) the quantity sold P 2 P 1 Surplus for consumer purchasing quantity D 2 D 1 Quantity © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 5 of 136

The Gains from Trade Figure 8. 1 (b) Price Total Producer surplus, PS S The up who sells S 0 has A producerall the individual a Addingsupply curve gives us the consumer’s value for on MC of P 0, but each P 1. That the of surpluses for gets pointeach unit the good. Given 1, (P 1 -P gives surplus gives Pto total 0) supply curve equal us producers will sell a total of S 1. producer surplus—the area between the supply and the price received—up to the quantity sold. P 1 P 0 Surplus for firm producing quantity S 0 S 1 Quantity © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 6 of 136

The Gains from Trade Figure 8. 1 (b) Price Total Producer surplus, PS S The up who sells S 0 has A producerall the individual a Addingsupply curve gives us the consumer’s value for on MC of P 0, but each P 1. That the of surpluses for gets pointeach unit the good. Given 1, (P 1 -P gives surplus gives Pto total 0) supply curve equal us producers will sell a total of S 1. producer surplus—the area between the supply and the price received—up to the quantity sold. P 1 P 0 Surplus for firm producing quantity S 0 S 1 Quantity © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 6 of 136

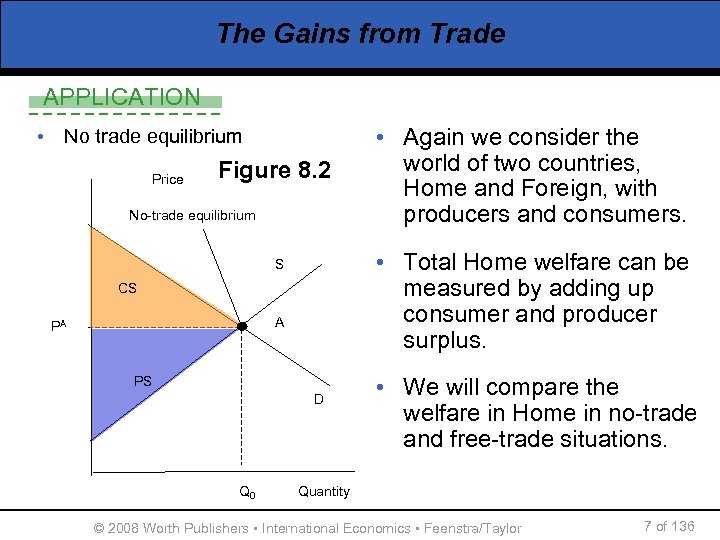

The Gains from Trade APPLICATION • No trade equilibrium Price Figure 8. 2 No-trade equilibrium • Total Home welfare can be measured by adding up consumer and producer surplus. S CS A PA PS D Q 0 • Again we consider the world of two countries, Home and Foreign, with producers and consumers. • We will compare the welfare in Home in no-trade and free-trade situations. Quantity © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 7 of 136

The Gains from Trade APPLICATION • No trade equilibrium Price Figure 8. 2 No-trade equilibrium • Total Home welfare can be measured by adding up consumer and producer surplus. S CS A PA PS D Q 0 • Again we consider the world of two countries, Home and Foreign, with producers and consumers. • We will compare the welfare in Home in no-trade and free-trade situations. Quantity © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 7 of 136

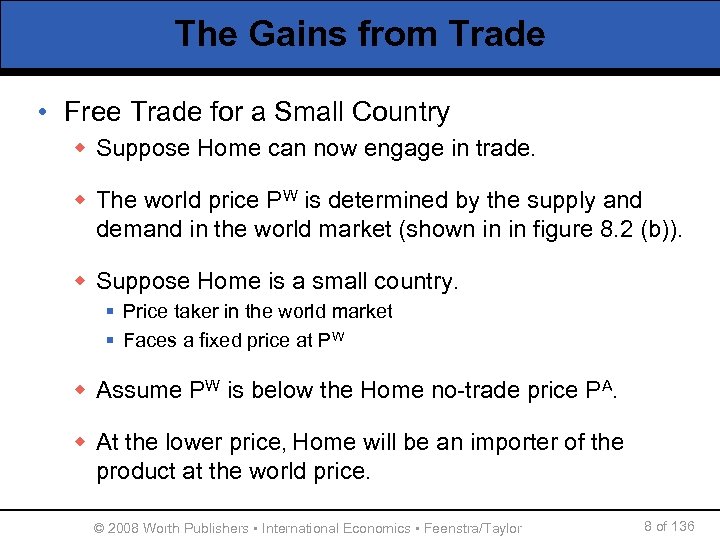

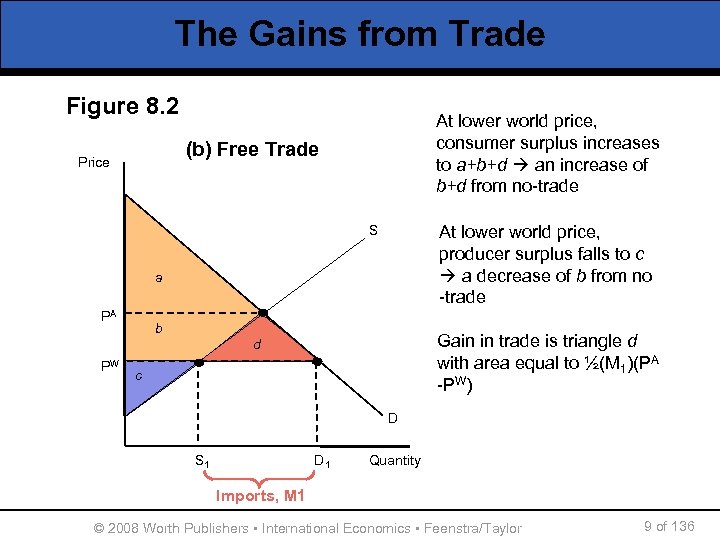

The Gains from Trade • Free Trade for a Small Country w Suppose Home can now engage in trade. w The world price PW is determined by the supply and demand in the world market (shown in in figure 8. 2 (b)). w Suppose Home is a small country. § Price taker in the world market § Faces a fixed price at PW w Assume PW is below the Home no-trade price PA. w At the lower price, Home will be an importer of the product at the world price. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 8 of 136

The Gains from Trade • Free Trade for a Small Country w Suppose Home can now engage in trade. w The world price PW is determined by the supply and demand in the world market (shown in in figure 8. 2 (b)). w Suppose Home is a small country. § Price taker in the world market § Faces a fixed price at PW w Assume PW is below the Home no-trade price PA. w At the lower price, Home will be an importer of the product at the world price. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 8 of 136

The Gains from Trade Figure 8. 2 At lower world price, consumer surplus increases to a+b+d an increase of b+d from no-trade (b) Free Trade Price S At lower world price, producer surplus falls to c a decrease of b from no -trade a PA b Gain in trade is triangle d with area equal to ½(M 1)(PA -PW) d PW c D S 1 D 1 Quantity Imports, M 1 © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 9 of 136

The Gains from Trade Figure 8. 2 At lower world price, consumer surplus increases to a+b+d an increase of b+d from no-trade (b) Free Trade Price S At lower world price, producer surplus falls to c a decrease of b from no -trade a PA b Gain in trade is triangle d with area equal to ½(M 1)(PA -PW) d PW c D S 1 D 1 Quantity Imports, M 1 © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 9 of 136

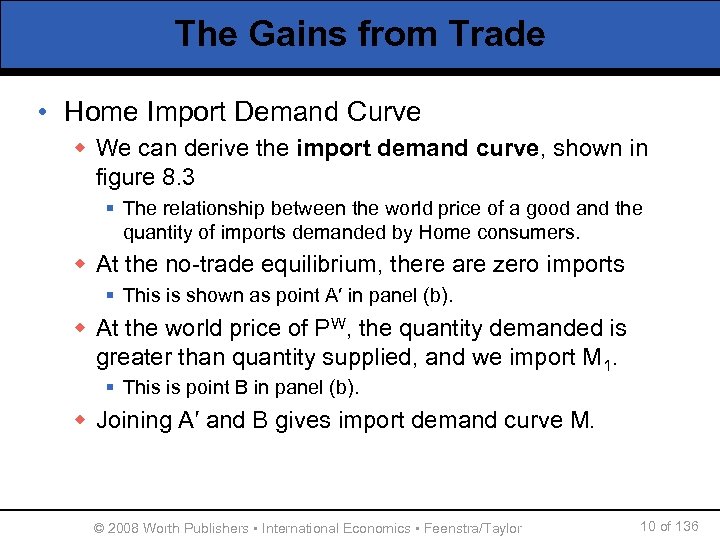

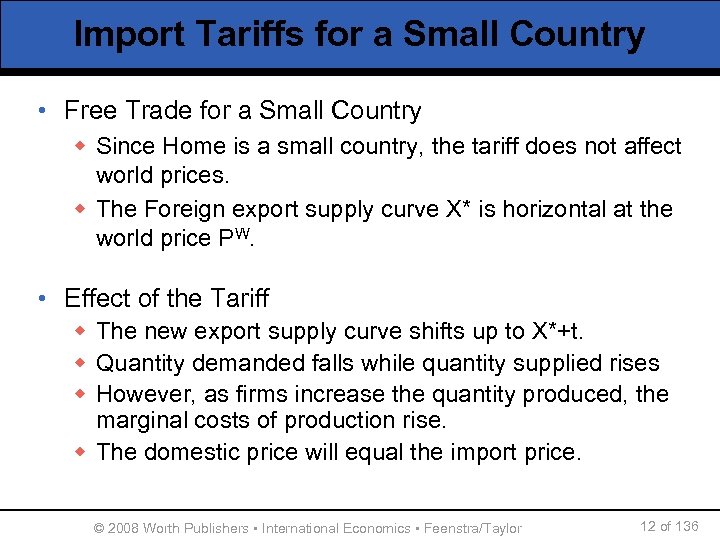

The Gains from Trade • Home Import Demand Curve w We can derive the import demand curve, shown in figure 8. 3 § The relationship between the world price of a good and the quantity of imports demanded by Home consumers. w At the no-trade equilibrium, there are zero imports § This is shown as point A′ in panel (b). w At the world price of PW, the quantity demanded is greater than quantity supplied, and we import M 1. § This is point B in panel (b). w Joining A′ and B gives import demand curve M. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 10 of 136

The Gains from Trade • Home Import Demand Curve w We can derive the import demand curve, shown in figure 8. 3 § The relationship between the world price of a good and the quantity of imports demanded by Home consumers. w At the no-trade equilibrium, there are zero imports § This is shown as point A′ in panel (b). w At the world price of PW, the quantity demanded is greater than quantity supplied, and we import M 1. § This is point B in panel (b). w Joining A′ and B gives import demand curve M. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 10 of 136

The Gains from Trade Figure 8. 3 (b) (a) Price No-trade equilibrium Price S A' PA Each point on the import demand curve is a point that corresponds to Home imports at a given Home price A B PW Import demand curve, M D S 1 Q 0 D 1 Quantity M 1 Imports, M 1 © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 11 of 136

The Gains from Trade Figure 8. 3 (b) (a) Price No-trade equilibrium Price S A' PA Each point on the import demand curve is a point that corresponds to Home imports at a given Home price A B PW Import demand curve, M D S 1 Q 0 D 1 Quantity M 1 Imports, M 1 © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 11 of 136

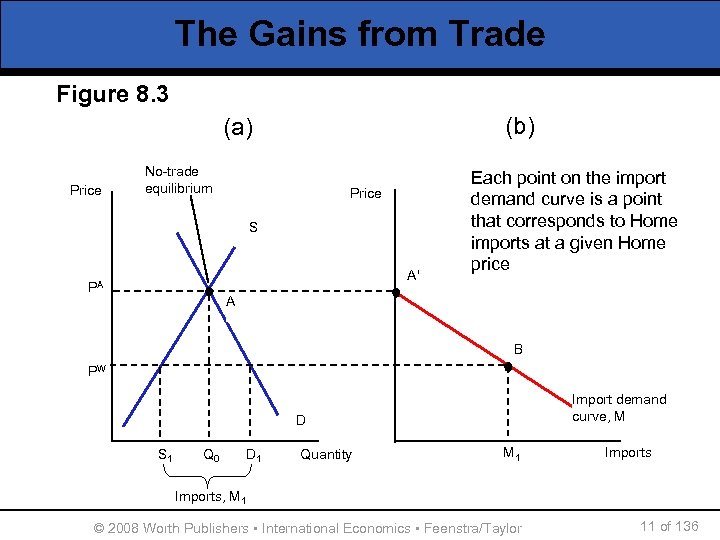

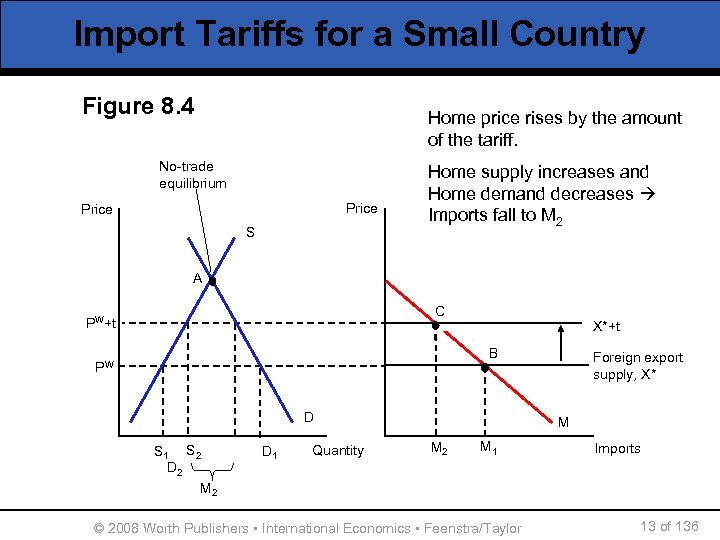

Import Tariffs for a Small Country • Free Trade for a Small Country w Since Home is a small country, the tariff does not affect world prices. w The Foreign export supply curve X* is horizontal at the world price PW. • Effect of the Tariff w The new export supply curve shifts up to X*+t. w Quantity demanded falls while quantity supplied rises w However, as firms increase the quantity produced, the marginal costs of production rise. w The domestic price will equal the import price. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 12 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Small Country • Free Trade for a Small Country w Since Home is a small country, the tariff does not affect world prices. w The Foreign export supply curve X* is horizontal at the world price PW. • Effect of the Tariff w The new export supply curve shifts up to X*+t. w Quantity demanded falls while quantity supplied rises w However, as firms increase the quantity produced, the marginal costs of production rise. w The domestic price will equal the import price. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 12 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Small Country Figure 8. 4 Home price rises by the amount of the tariff. No-trade equilibrium Price S Home supply increases and Home demand decreases Imports fall to M 2 A C PW+t X*+t B PW D S 1 S 2 D 2 M 2 D 1 Quantity Foreign export supply, X* M M 2 M 1 © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor Imports 13 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Small Country Figure 8. 4 Home price rises by the amount of the tariff. No-trade equilibrium Price S Home supply increases and Home demand decreases Imports fall to M 2 A C PW+t X*+t B PW D S 1 S 2 D 2 M 2 D 1 Quantity Foreign export supply, X* M M 2 M 1 © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor Imports 13 of 136

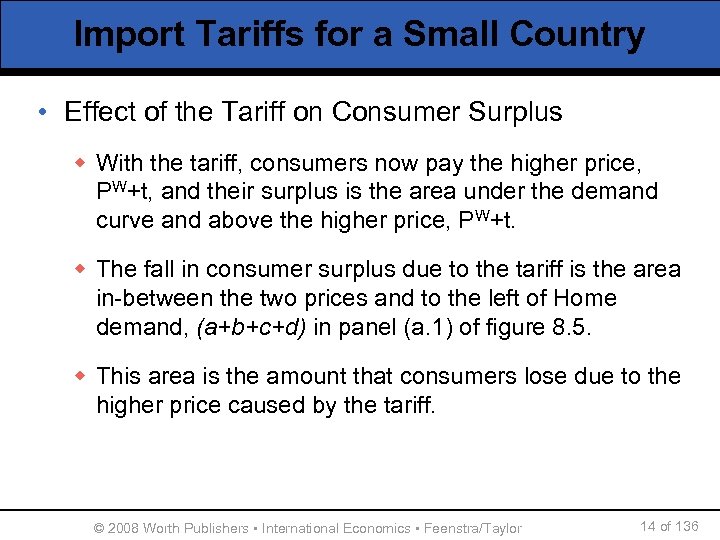

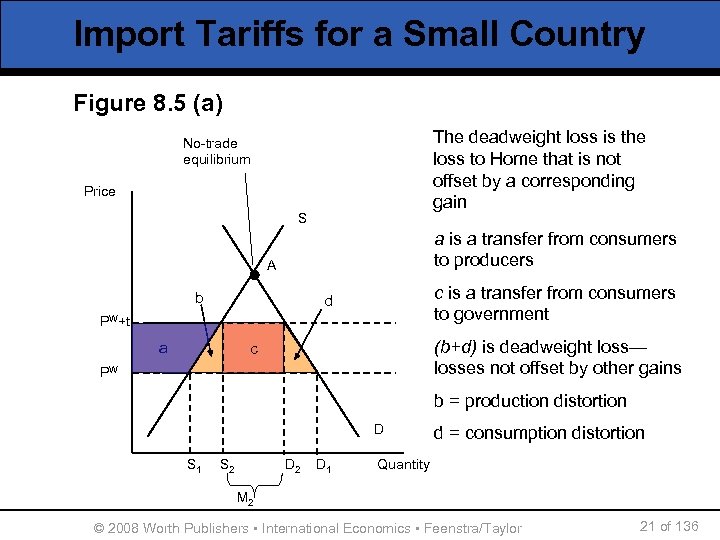

Import Tariffs for a Small Country • Effect of the Tariff on Consumer Surplus w With the tariff, consumers now pay the higher price, PW+t, and their surplus is the area under the demand curve and above the higher price, PW+t. w The fall in consumer surplus due to the tariff is the area in-between the two prices and to the left of Home demand, (a+b+c+d) in panel (a. 1) of figure 8. 5. w This area is the amount that consumers lose due to the higher price caused by the tariff. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 14 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Small Country • Effect of the Tariff on Consumer Surplus w With the tariff, consumers now pay the higher price, PW+t, and their surplus is the area under the demand curve and above the higher price, PW+t. w The fall in consumer surplus due to the tariff is the area in-between the two prices and to the left of Home demand, (a+b+c+d) in panel (a. 1) of figure 8. 5. w This area is the amount that consumers lose due to the higher price caused by the tariff. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 14 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Small Country Figure 8. 5 (a. 1) No-trade equilibrium Lost consumer surplus due to the higher price with the tariff is equal to the shaded area (a+b+c+d) Price S A b d PW+t a c PW D S 1 S 2 D 1 Quantity M 2 © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 15 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Small Country Figure 8. 5 (a. 1) No-trade equilibrium Lost consumer surplus due to the higher price with the tariff is equal to the shaded area (a+b+c+d) Price S A b d PW+t a c PW D S 1 S 2 D 1 Quantity M 2 © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 15 of 136

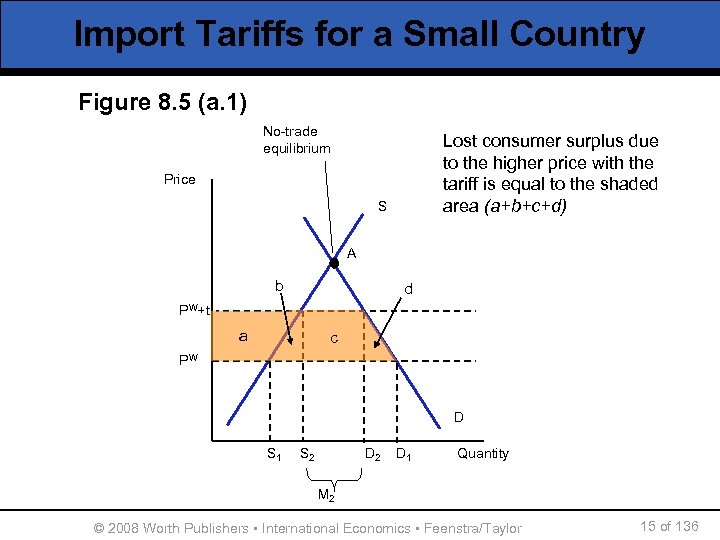

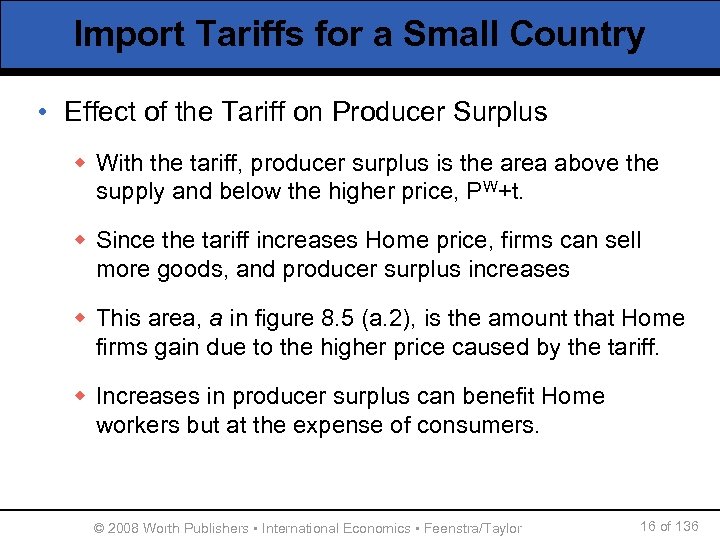

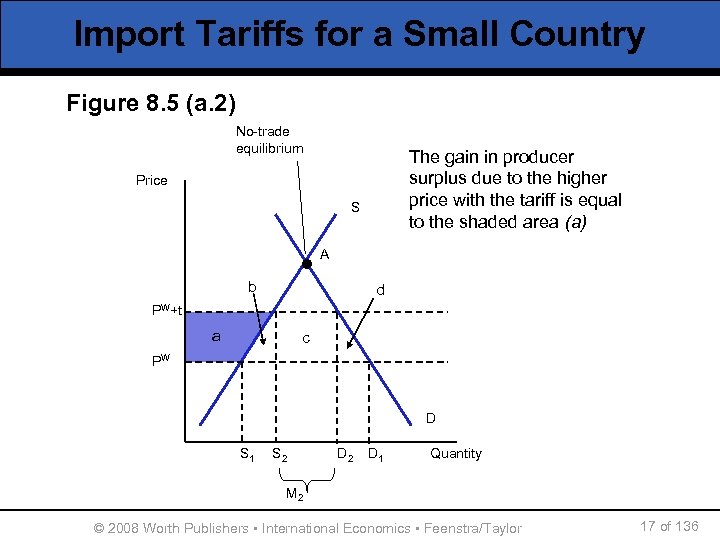

Import Tariffs for a Small Country • Effect of the Tariff on Producer Surplus w With the tariff, producer surplus is the area above the supply and below the higher price, PW+t. w Since the tariff increases Home price, firms can sell more goods, and producer surplus increases w This area, a in figure 8. 5 (a. 2), is the amount that Home firms gain due to the higher price caused by the tariff. w Increases in producer surplus can benefit Home workers but at the expense of consumers. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 16 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Small Country • Effect of the Tariff on Producer Surplus w With the tariff, producer surplus is the area above the supply and below the higher price, PW+t. w Since the tariff increases Home price, firms can sell more goods, and producer surplus increases w This area, a in figure 8. 5 (a. 2), is the amount that Home firms gain due to the higher price caused by the tariff. w Increases in producer surplus can benefit Home workers but at the expense of consumers. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 16 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Small Country Figure 8. 5 (a. 2) No-trade equilibrium The gain in producer surplus due to the higher price with the tariff is equal to the shaded area (a) Price S A b d PW+t a c PW D S 1 S 2 D 1 Quantity M 2 © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 17 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Small Country Figure 8. 5 (a. 2) No-trade equilibrium The gain in producer surplus due to the higher price with the tariff is equal to the shaded area (a) Price S A b d PW+t a c PW D S 1 S 2 D 1 Quantity M 2 © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 17 of 136

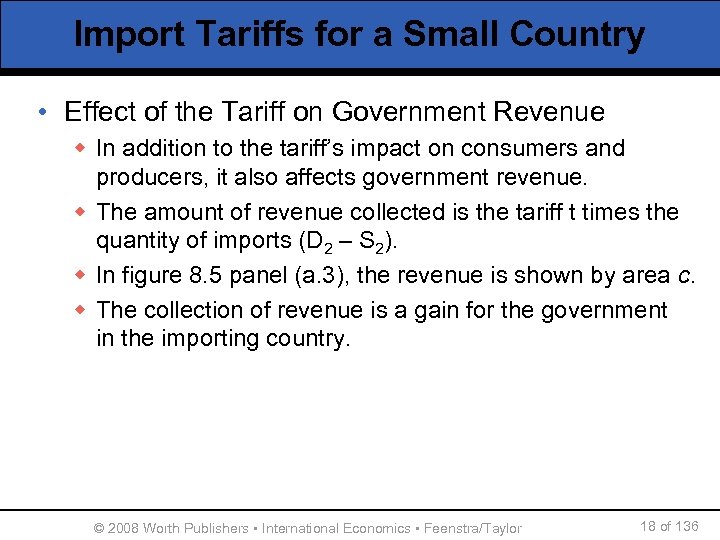

Import Tariffs for a Small Country • Effect of the Tariff on Government Revenue w In addition to the tariff’s impact on consumers and producers, it also affects government revenue. w The amount of revenue collected is the tariff t times the quantity of imports (D 2 – S 2). w In figure 8. 5 panel (a. 3), the revenue is shown by area c. w The collection of revenue is a gain for the government in the importing country. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 18 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Small Country • Effect of the Tariff on Government Revenue w In addition to the tariff’s impact on consumers and producers, it also affects government revenue. w The amount of revenue collected is the tariff t times the quantity of imports (D 2 – S 2). w In figure 8. 5 panel (a. 3), the revenue is shown by area c. w The collection of revenue is a gain for the government in the importing country. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 18 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Small Country Figure 8. 5 (a. 3) The gain in government revenue due to the tariff is equal to the shaded area (c) No-trade equilibrium Price S A b d This equals the tariff, t, times the quantity of imports, M 2 PW+t a c PW D S 1 S 2 D 1 Quantity M 2 © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 19 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Small Country Figure 8. 5 (a. 3) The gain in government revenue due to the tariff is equal to the shaded area (c) No-trade equilibrium Price S A b d This equals the tariff, t, times the quantity of imports, M 2 PW+t a c PW D S 1 S 2 D 1 Quantity M 2 © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 19 of 136

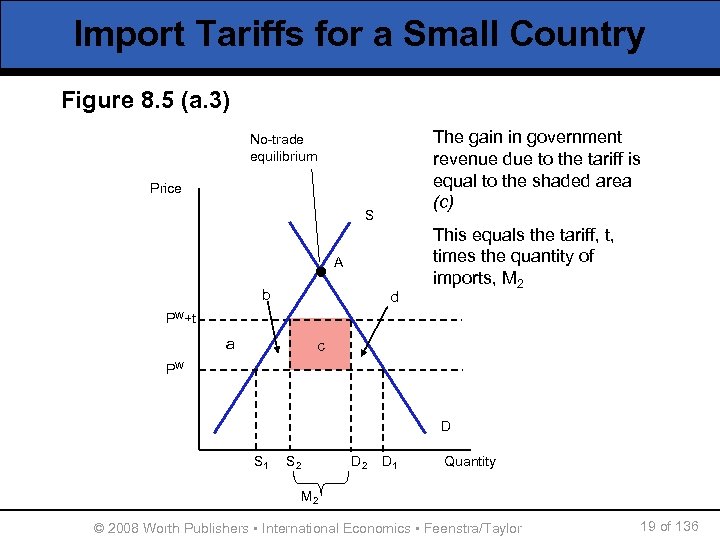

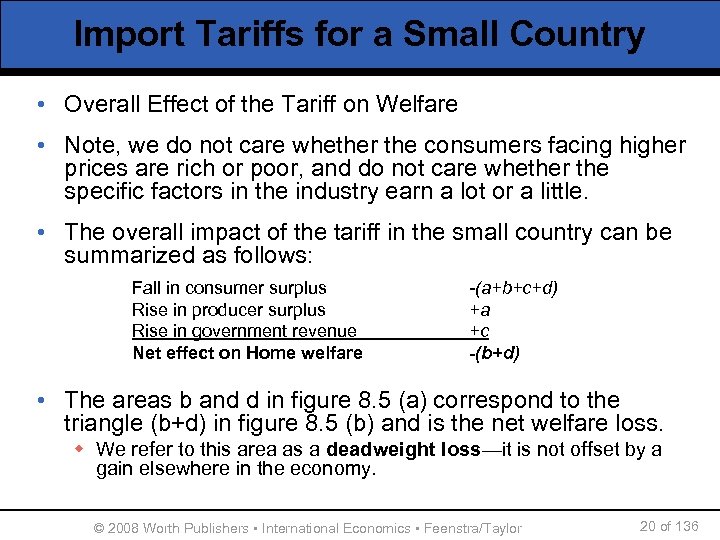

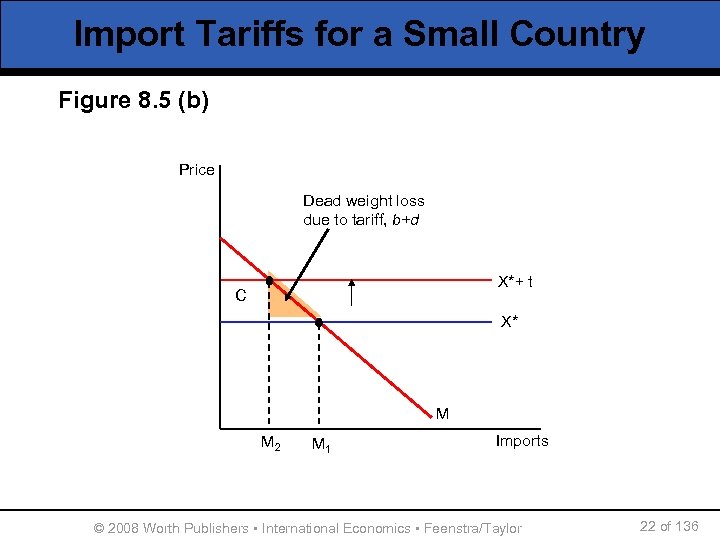

Import Tariffs for a Small Country • Overall Effect of the Tariff on Welfare • Note, we do not care whether the consumers facing higher prices are rich or poor, and do not care whether the specific factors in the industry earn a lot or a little. • The overall impact of the tariff in the small country can be summarized as follows: Fall in consumer surplus Rise in producer surplus Rise in government revenue Net effect on Home welfare -(a+b+c+d) +a +c -(b+d) • The areas b and d in figure 8. 5 (a) correspond to the triangle (b+d) in figure 8. 5 (b) and is the net welfare loss. w We refer to this area as a deadweight loss—it is not offset by a gain elsewhere in the economy. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 20 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Small Country • Overall Effect of the Tariff on Welfare • Note, we do not care whether the consumers facing higher prices are rich or poor, and do not care whether the specific factors in the industry earn a lot or a little. • The overall impact of the tariff in the small country can be summarized as follows: Fall in consumer surplus Rise in producer surplus Rise in government revenue Net effect on Home welfare -(a+b+c+d) +a +c -(b+d) • The areas b and d in figure 8. 5 (a) correspond to the triangle (b+d) in figure 8. 5 (b) and is the net welfare loss. w We refer to this area as a deadweight loss—it is not offset by a gain elsewhere in the economy. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 20 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Small Country Figure 8. 5 (a) The deadweight loss is the loss to Home that is not offset by a corresponding gain No-trade equilibrium Price S a is a transfer from consumers to producers A b c is a transfer from consumers to government d PW+t a (b+d) is deadweight loss— losses not offset by other gains c PW b = production distortion D S 1 S 2 D 1 d = consumption distortion Quantity M 2 © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 21 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Small Country Figure 8. 5 (a) The deadweight loss is the loss to Home that is not offset by a corresponding gain No-trade equilibrium Price S a is a transfer from consumers to producers A b c is a transfer from consumers to government d PW+t a (b+d) is deadweight loss— losses not offset by other gains c PW b = production distortion D S 1 S 2 D 1 d = consumption distortion Quantity M 2 © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 21 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Small Country Figure 8. 5 (b) Price Dead weight loss due to tariff, b+d X*+ t C X* M M 2 M 1 Imports © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 22 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Small Country Figure 8. 5 (b) Price Dead weight loss due to tariff, b+d X*+ t C X* M M 2 M 1 Imports © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 22 of 136

Why are Tariffs Used? • Why do so many countries use tariffs if they always lead to deadweight losses? w One idea is that developing countries do not have any other source of revenue. § Import tariffs are “easy-to-collect” relative to income taxes. § However, to the extent that developing countries recognize that tariffs have a higher deadweight loss, we would expect that over time they will shift away from such “easy-to-collect” taxes. w A second reason is politics. § The might government care more about producer surplus than consumer surplus. § The benefits to producers (and their workers) are typically more concentrated on specific firms and states than the costs to consumers, which are spread nationwide. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 23 of 136

Why are Tariffs Used? • Why do so many countries use tariffs if they always lead to deadweight losses? w One idea is that developing countries do not have any other source of revenue. § Import tariffs are “easy-to-collect” relative to income taxes. § However, to the extent that developing countries recognize that tariffs have a higher deadweight loss, we would expect that over time they will shift away from such “easy-to-collect” taxes. w A second reason is politics. § The might government care more about producer surplus than consumer surplus. § The benefits to producers (and their workers) are typically more concentrated on specific firms and states than the costs to consumers, which are spread nationwide. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 23 of 136

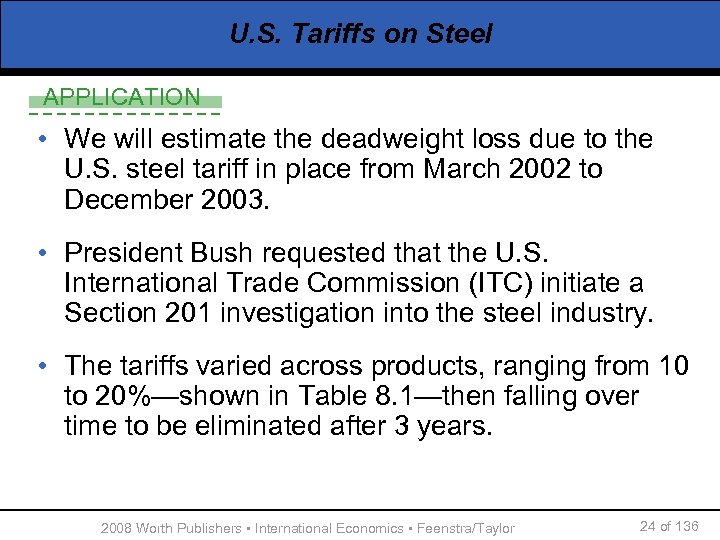

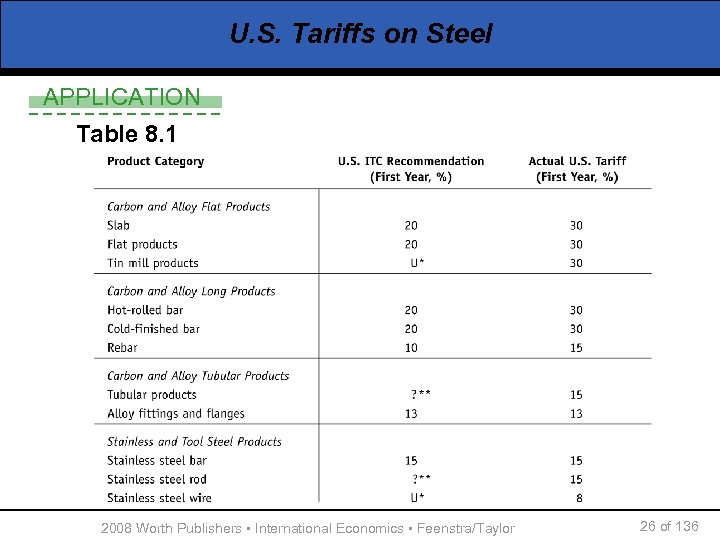

U. S. Tariffs on Steel APPLICATION • We will estimate the deadweight loss due to the U. S. steel tariff in place from March 2002 to December 2003. • President Bush requested that the U. S. International Trade Commission (ITC) initiate a Section 201 investigation into the steel industry. • The tariffs varied across products, ranging from 10 to 20%—shown in Table 8. 1—then falling over time to be eliminated after 3 years. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 24 of 136

U. S. Tariffs on Steel APPLICATION • We will estimate the deadweight loss due to the U. S. steel tariff in place from March 2002 to December 2003. • President Bush requested that the U. S. International Trade Commission (ITC) initiate a Section 201 investigation into the steel industry. • The tariffs varied across products, ranging from 10 to 20%—shown in Table 8. 1—then falling over time to be eliminated after 3 years. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 24 of 136

U. S. Tariffs on Steel APPLICATION • President Bush took the recommendation of the ITC but applied even higher tariffs, ranging from 8% to 30%. • Knowing the U. S. trading partners would be upset by this, President Bush exempted some countries from the tariffs. w These included Canada, Mexico, Jordan, and Israel, which all have free trade agreements with the U. S. , and 100 small developing countries that were exporting only a very small amount of steel to the U. S. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 25 of 136

U. S. Tariffs on Steel APPLICATION • President Bush took the recommendation of the ITC but applied even higher tariffs, ranging from 8% to 30%. • Knowing the U. S. trading partners would be upset by this, President Bush exempted some countries from the tariffs. w These included Canada, Mexico, Jordan, and Israel, which all have free trade agreements with the U. S. , and 100 small developing countries that were exporting only a very small amount of steel to the U. S. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 25 of 136

U. S. Tariffs on Steel APPLICATION Table 8. 1 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 26 of 136

U. S. Tariffs on Steel APPLICATION Table 8. 1 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 26 of 136

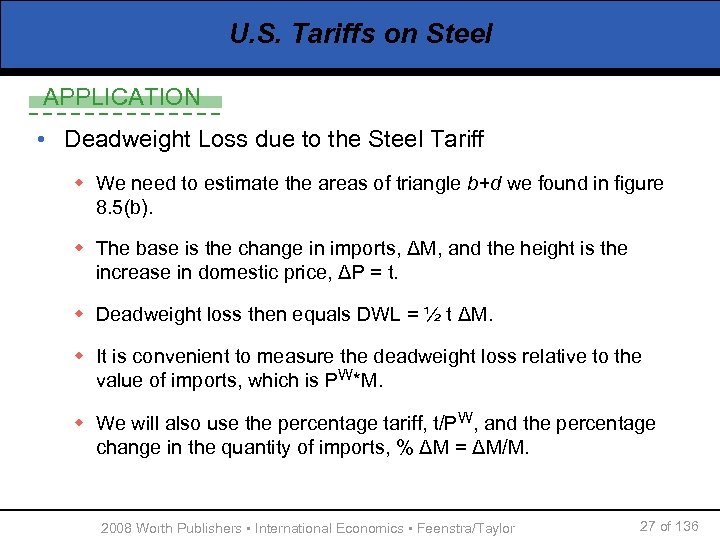

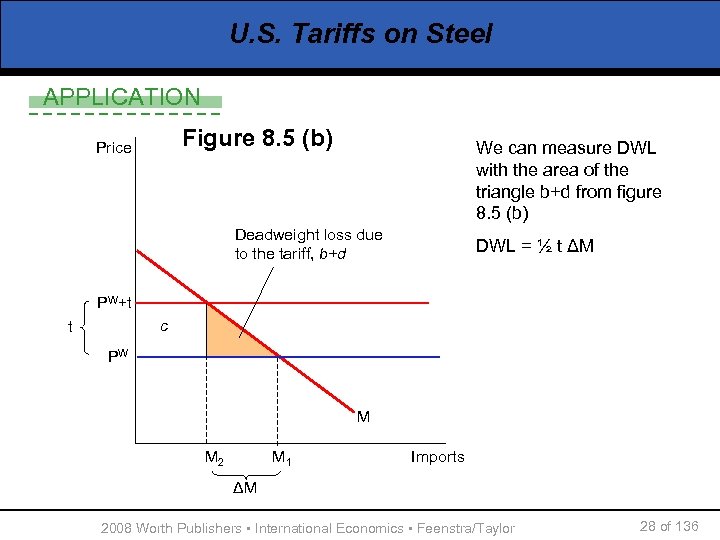

U. S. Tariffs on Steel APPLICATION • Deadweight Loss due to the Steel Tariff w We need to estimate the areas of triangle b+d we found in figure 8. 5(b). w The base is the change in imports, ΔM, and the height is the increase in domestic price, ΔP = t. w Deadweight loss then equals DWL = ½ t ΔM. w It is convenient to measure the deadweight loss relative to the value of imports, which is PW*M. w We will also use the percentage tariff, t/PW, and the percentage change in the quantity of imports, % ΔM = ΔM/M. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 27 of 136

U. S. Tariffs on Steel APPLICATION • Deadweight Loss due to the Steel Tariff w We need to estimate the areas of triangle b+d we found in figure 8. 5(b). w The base is the change in imports, ΔM, and the height is the increase in domestic price, ΔP = t. w Deadweight loss then equals DWL = ½ t ΔM. w It is convenient to measure the deadweight loss relative to the value of imports, which is PW*M. w We will also use the percentage tariff, t/PW, and the percentage change in the quantity of imports, % ΔM = ΔM/M. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 27 of 136

U. S. Tariffs on Steel APPLICATION Figure 8. 5 (b) Price We can measure DWL with the area of the triangle b+d from figure 8. 5 (b) Deadweight loss due to the tariff, b+d DWL = ½ t ΔM PW+t c t PW M M 2 M 1 Imports ΔM 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 28 of 136

U. S. Tariffs on Steel APPLICATION Figure 8. 5 (b) Price We can measure DWL with the area of the triangle b+d from figure 8. 5 (b) Deadweight loss due to the tariff, b+d DWL = ½ t ΔM PW+t c t PW M M 2 M 1 Imports ΔM 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 28 of 136

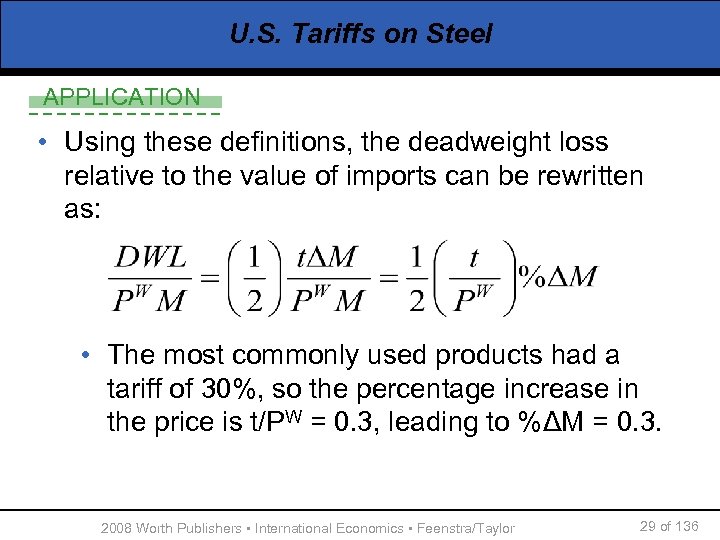

U. S. Tariffs on Steel APPLICATION • Using these definitions, the deadweight loss relative to the value of imports can be rewritten as: • The most commonly used products had a tariff of 30%, so the percentage increase in the price is t/PW = 0. 3, leading to %ΔM = 0. 3. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 29 of 136

U. S. Tariffs on Steel APPLICATION • Using these definitions, the deadweight loss relative to the value of imports can be rewritten as: • The most commonly used products had a tariff of 30%, so the percentage increase in the price is t/PW = 0. 3, leading to %ΔM = 0. 3. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 29 of 136

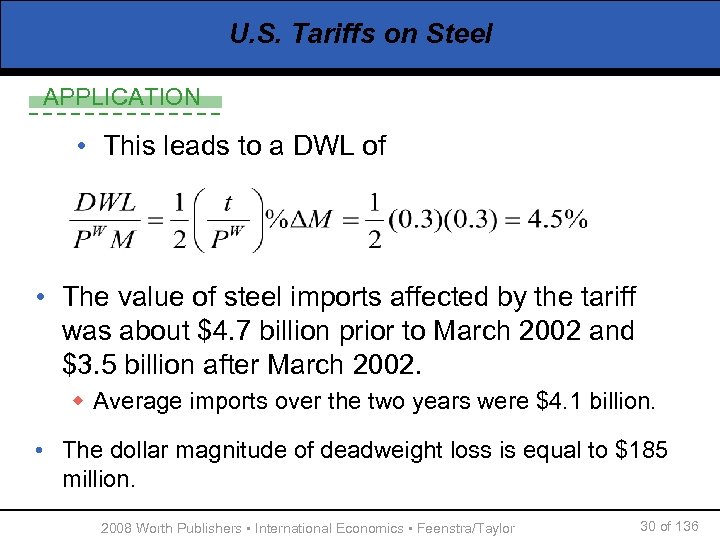

U. S. Tariffs on Steel APPLICATION • This leads to a DWL of • The value of steel imports affected by the tariff was about $4. 7 billion prior to March 2002 and $3. 5 billion after March 2002. w Average imports over the two years were $4. 1 billion. • The dollar magnitude of deadweight loss is equal to $185 million. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 30 of 136

U. S. Tariffs on Steel APPLICATION • This leads to a DWL of • The value of steel imports affected by the tariff was about $4. 7 billion prior to March 2002 and $3. 5 billion after March 2002. w Average imports over the two years were $4. 1 billion. • The dollar magnitude of deadweight loss is equal to $185 million. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 30 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Large Country • Under the small country assumption that we have used so far, the importing country is always harmed due to the tariff. w The small country is a world price taker. • If we consider a large enough importing country or a large country, however, then we might expect that its tariff will change the world price. w Its imports are large enough that it can affect world price with a change in its imports. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 31 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Large Country • Under the small country assumption that we have used so far, the importing country is always harmed due to the tariff. w The small country is a world price taker. • If we consider a large enough importing country or a large country, however, then we might expect that its tariff will change the world price. w Its imports are large enough that it can affect world price with a change in its imports. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 31 of 136

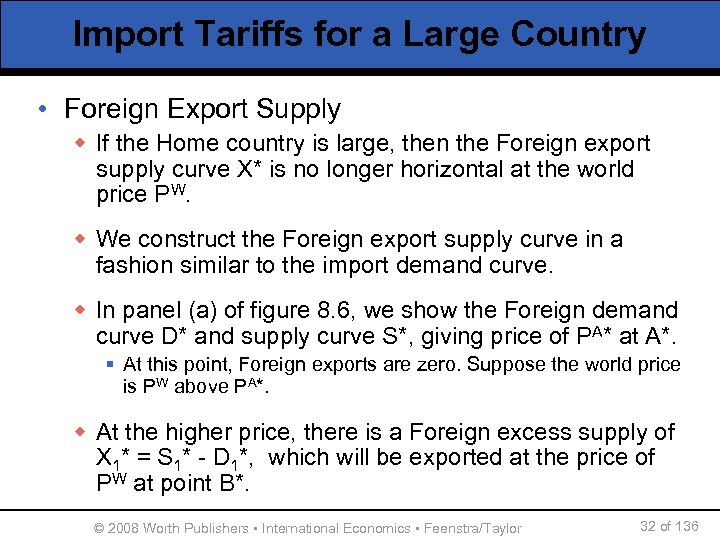

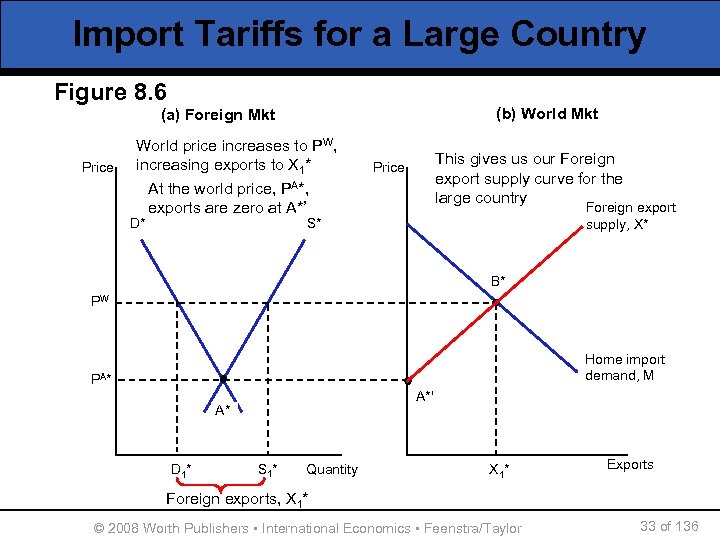

Import Tariffs for a Large Country • Foreign Export Supply w If the Home country is large, then the Foreign export supply curve X* is no longer horizontal at the world price PW. w We construct the Foreign export supply curve in a fashion similar to the import demand curve. w In panel (a) of figure 8. 6, we show the Foreign demand curve D* and supply curve S*, giving price of PA* at A*. § At this point, Foreign exports are zero. Suppose the world price is PW above PA*. w At the higher price, there is a Foreign excess supply of X 1* = S 1* - D 1*, which will be exported at the price of PW at point B*. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 32 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Large Country • Foreign Export Supply w If the Home country is large, then the Foreign export supply curve X* is no longer horizontal at the world price PW. w We construct the Foreign export supply curve in a fashion similar to the import demand curve. w In panel (a) of figure 8. 6, we show the Foreign demand curve D* and supply curve S*, giving price of PA* at A*. § At this point, Foreign exports are zero. Suppose the world price is PW above PA*. w At the higher price, there is a Foreign excess supply of X 1* = S 1* - D 1*, which will be exported at the price of PW at point B*. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 32 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Large Country Figure 8. 6 (b) World Mkt (a) Foreign Mkt Price World price increases to PW, increasing exports to X 1* D* This gives us our Foreign export supply curve for the large country Price At the world price, PA*, exports are zero at A*’ Foreign export supply, X* S* B* PW Home import demand, M PA* A*' A* D 1* S 1* Quantity X 1* Exports Foreign exports, X 1* © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 33 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Large Country Figure 8. 6 (b) World Mkt (a) Foreign Mkt Price World price increases to PW, increasing exports to X 1* D* This gives us our Foreign export supply curve for the large country Price At the world price, PA*, exports are zero at A*’ Foreign export supply, X* S* B* PW Home import demand, M PA* A*' A* D 1* S 1* Quantity X 1* Exports Foreign exports, X 1* © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 33 of 136

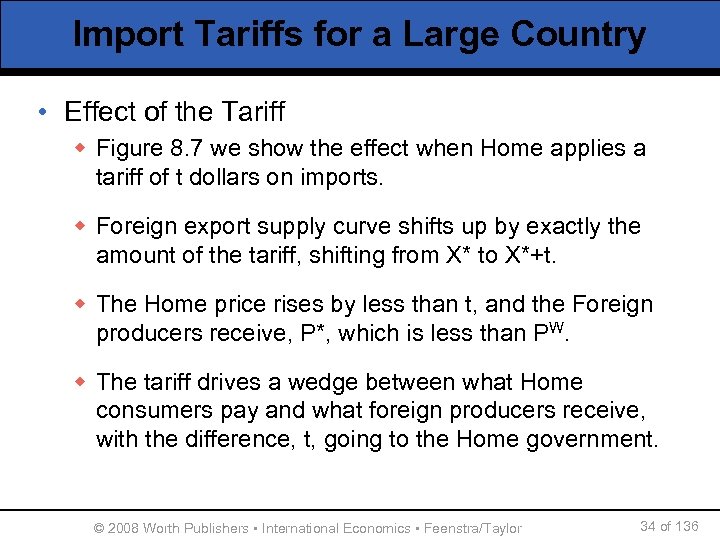

Import Tariffs for a Large Country • Effect of the Tariff w Figure 8. 7 we show the effect when Home applies a tariff of t dollars on imports. w Foreign export supply curve shifts up by exactly the amount of the tariff, shifting from X* to X*+t. w The Home price rises by less than t, and the Foreign producers receive, P*, which is less than PW. w The tariff drives a wedge between what Home consumers pay and what foreign producers receive, with the difference, t, going to the Home government. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 34 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Large Country • Effect of the Tariff w Figure 8. 7 we show the effect when Home applies a tariff of t dollars on imports. w Foreign export supply curve shifts up by exactly the amount of the tariff, shifting from X* to X*+t. w The Home price rises by less than t, and the Foreign producers receive, P*, which is less than PW. w The tariff drives a wedge between what Home consumers pay and what foreign producers receive, with the difference, t, going to the Home government. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 34 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Large Country Figure 8. 7 (without welfare effects) (a) Home market Price (b) Foreign market Price No-trade equilibrium X*+t S A X* t C P*+t t t PW P* B* C* D M S 1 S 2 D 1 Quantity M 2 M 1 Imports M 2 M 1 © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 35 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Large Country Figure 8. 7 (without welfare effects) (a) Home market Price (b) Foreign market Price No-trade equilibrium X*+t S A X* t C P*+t t t PW P* B* C* D M S 1 S 2 D 1 Quantity M 2 M 1 Imports M 2 M 1 © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 35 of 136

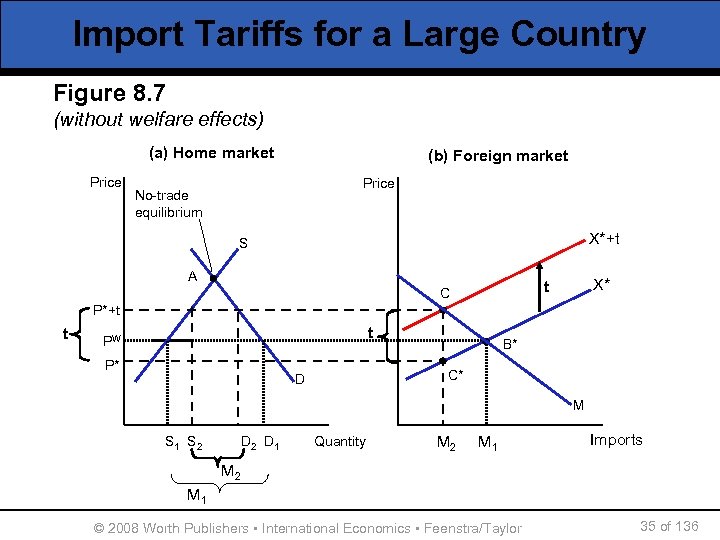

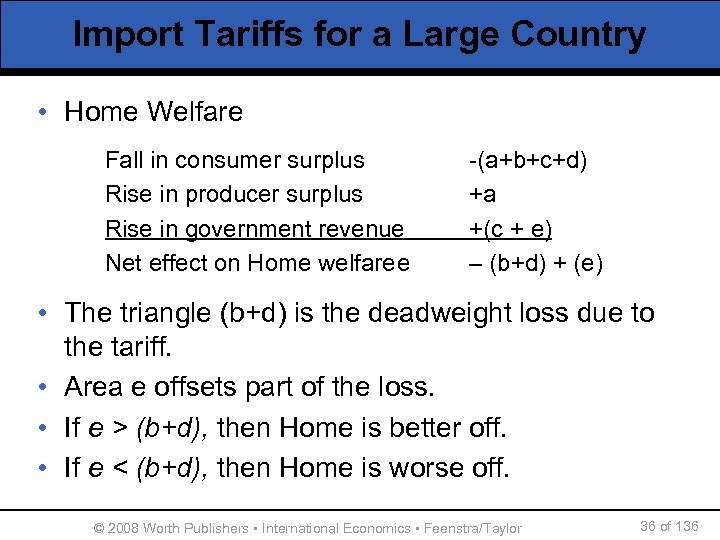

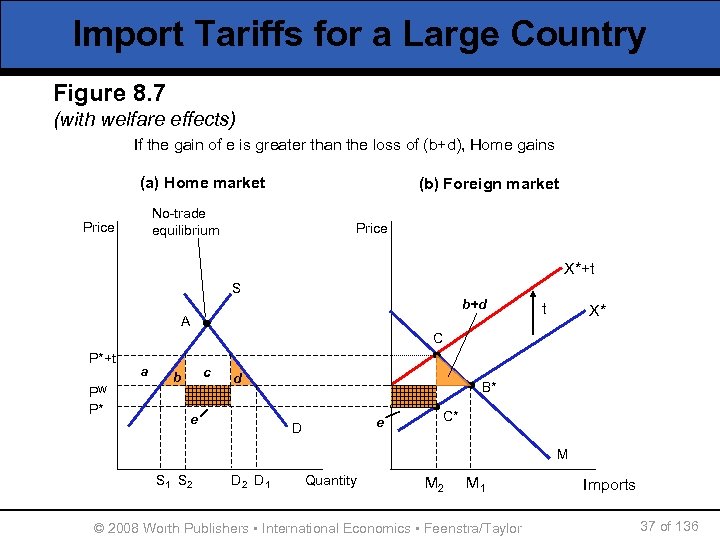

Import Tariffs for a Large Country • Home Welfare Fall in consumer surplus Rise in producer surplus Rise in government revenue Net effect on Home welfaree -(a+b+c+d) +a +(c + e) – (b+d) + (e) • The triangle (b+d) is the deadweight loss due to the tariff. • Area e offsets part of the loss. • If e > (b+d), then Home is better off. • If e < (b+d), then Home is worse off. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 36 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Large Country • Home Welfare Fall in consumer surplus Rise in producer surplus Rise in government revenue Net effect on Home welfaree -(a+b+c+d) +a +(c + e) – (b+d) + (e) • The triangle (b+d) is the deadweight loss due to the tariff. • Area e offsets part of the loss. • If e > (b+d), then Home is better off. • If e < (b+d), then Home is worse off. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 36 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Large Country Figure 8. 7 (with welfare effects) If the gain of e is greater than the loss of (b+d), Home gains (a) Home market (b) Foreign market No-trade equilibrium Price X*+t S b+d A t X* C P*+t PW P* a c b d e B* e D C* M S 1 S 2 D 1 Quantity M 2 M 1 © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor Imports 37 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Large Country Figure 8. 7 (with welfare effects) If the gain of e is greater than the loss of (b+d), Home gains (a) Home market (b) Foreign market No-trade equilibrium Price X*+t S b+d A t X* C P*+t PW P* a c b d e B* e D C* M S 1 S 2 D 1 Quantity M 2 M 1 © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor Imports 37 of 136

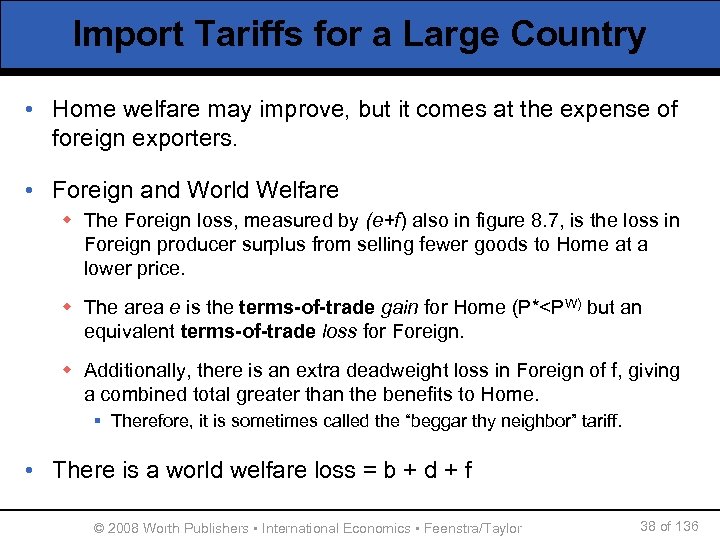

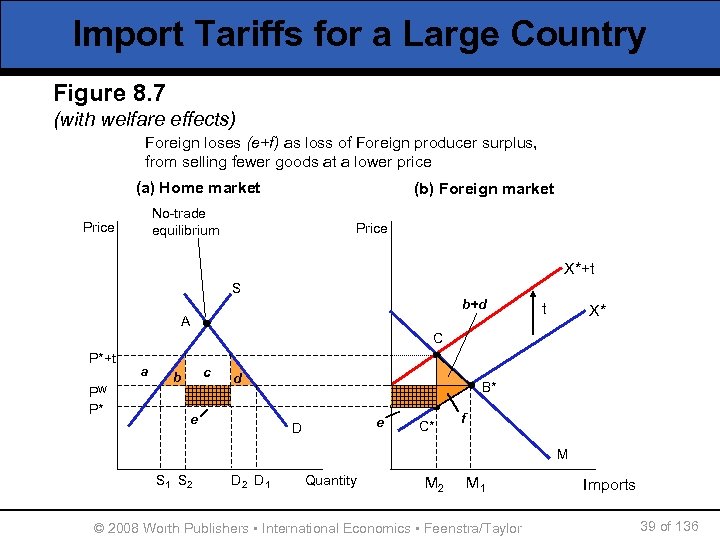

Import Tariffs for a Large Country • Home welfare may improve, but it comes at the expense of foreign exporters. • Foreign and World Welfare w The Foreign loss, measured by (e+f) also in figure 8. 7, is the loss in Foreign producer surplus from selling fewer goods to Home at a lower price. w The area e is the terms-of-trade gain for Home (P*

Import Tariffs for a Large Country • Home welfare may improve, but it comes at the expense of foreign exporters. • Foreign and World Welfare w The Foreign loss, measured by (e+f) also in figure 8. 7, is the loss in Foreign producer surplus from selling fewer goods to Home at a lower price. w The area e is the terms-of-trade gain for Home (P*

Import Tariffs for a Large Country Figure 8. 7 (with welfare effects) Foreign loses (e+f) as loss of Foreign producer surplus, from selling fewer goods at a lower price (a) Home market (b) Foreign market No-trade equilibrium Price X*+t S b+d A t X* C P*+t PW P* a c b d e B* e D C* f M S 1 S 2 D 1 Quantity M 2 M 1 © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor Imports 39 of 136

Import Tariffs for a Large Country Figure 8. 7 (with welfare effects) Foreign loses (e+f) as loss of Foreign producer surplus, from selling fewer goods at a lower price (a) Home market (b) Foreign market No-trade equilibrium Price X*+t S b+d A t X* C P*+t PW P* a c b d e B* e D C* f M S 1 S 2 D 1 Quantity M 2 M 1 © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor Imports 39 of 136

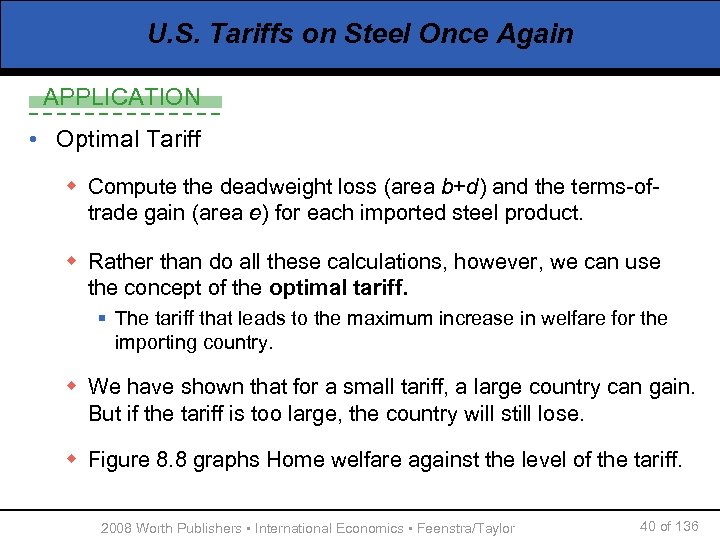

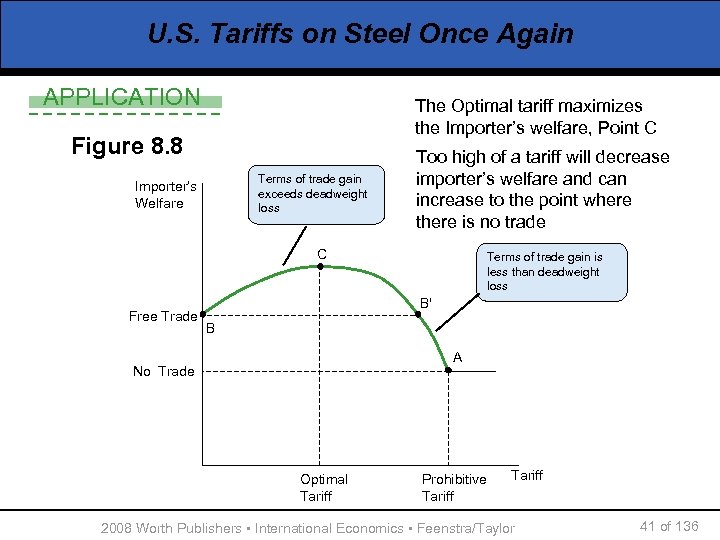

U. S. Tariffs on Steel Once Again APPLICATION • Optimal Tariff w Compute the deadweight loss (area b+d) and the terms-oftrade gain (area e) for each imported steel product. w Rather than do all these calculations, however, we can use the concept of the optimal tariff. § The tariff that leads to the maximum increase in welfare for the importing country. w We have shown that for a small tariff, a large country can gain. But if the tariff is too large, the country will still lose. w Figure 8. 8 graphs Home welfare against the level of the tariff. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 40 of 136

U. S. Tariffs on Steel Once Again APPLICATION • Optimal Tariff w Compute the deadweight loss (area b+d) and the terms-oftrade gain (area e) for each imported steel product. w Rather than do all these calculations, however, we can use the concept of the optimal tariff. § The tariff that leads to the maximum increase in welfare for the importing country. w We have shown that for a small tariff, a large country can gain. But if the tariff is too large, the country will still lose. w Figure 8. 8 graphs Home welfare against the level of the tariff. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 40 of 136

U. S. Tariffs on Steel Once Again APPLICATION The Optimal tariff maximizes the Importer’s welfare, Point C Figure 8. 8 Terms of trade gain exceeds deadweight loss Importer’s Welfare Too high of a tariff will decrease importer’s welfare and can increase to the point where there is no trade C Free Trade Terms of trade gain is less than deadweight loss B' B A No Trade Optimal Tariff Prohibitive Tariff 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 41 of 136

U. S. Tariffs on Steel Once Again APPLICATION The Optimal tariff maximizes the Importer’s welfare, Point C Figure 8. 8 Terms of trade gain exceeds deadweight loss Importer’s Welfare Too high of a tariff will decrease importer’s welfare and can increase to the point where there is no trade C Free Trade Terms of trade gain is less than deadweight loss B' B A No Trade Optimal Tariff Prohibitive Tariff 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 41 of 136

U. S. Tariffs on Steel Once Again APPLICATION • Optimal Tariff Formula w The optimal tariff depends on the elasticity of Foreign export supply, EX*. • Optimal Tariff Formula Optimal Tariff = 1/EX*. w For a small importing country, the elasticity of Foreign export supply is infinite, and so the optimal tariff is zero. w As the elasticity of Foreign export supply decreases, Foreign export supply curve is steeper, the optimal tariff is higher. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 42 of 136

U. S. Tariffs on Steel Once Again APPLICATION • Optimal Tariff Formula w The optimal tariff depends on the elasticity of Foreign export supply, EX*. • Optimal Tariff Formula Optimal Tariff = 1/EX*. w For a small importing country, the elasticity of Foreign export supply is infinite, and so the optimal tariff is zero. w As the elasticity of Foreign export supply decreases, Foreign export supply curve is steeper, the optimal tariff is higher. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 42 of 136

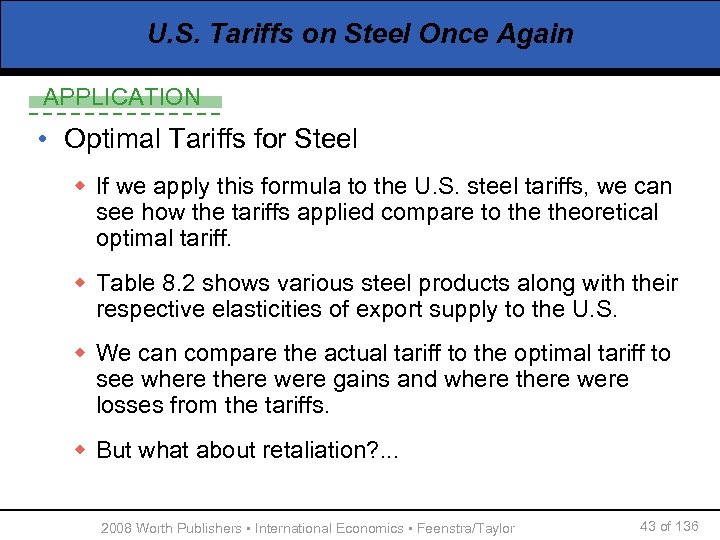

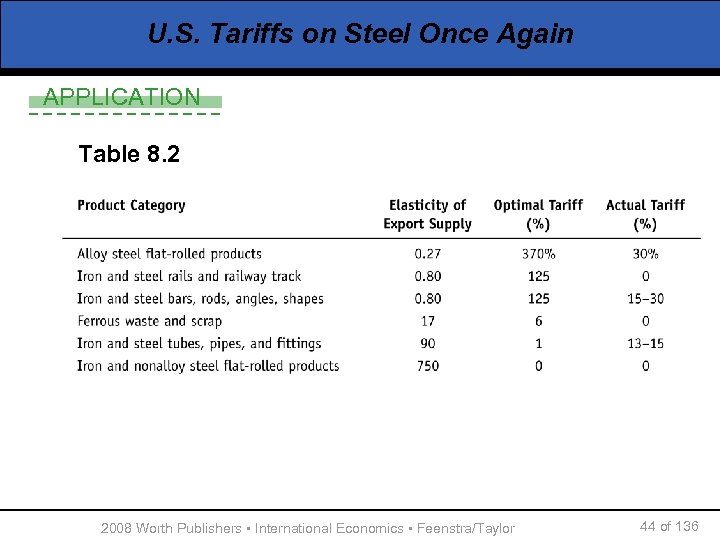

U. S. Tariffs on Steel Once Again APPLICATION • Optimal Tariffs for Steel w If we apply this formula to the U. S. steel tariffs, we can see how the tariffs applied compare to theoretical optimal tariff. w Table 8. 2 shows various steel products along with their respective elasticities of export supply to the U. S. w We can compare the actual tariff to the optimal tariff to see where there were gains and where there were losses from the tariffs. w But what about retaliation? . . . 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 43 of 136

U. S. Tariffs on Steel Once Again APPLICATION • Optimal Tariffs for Steel w If we apply this formula to the U. S. steel tariffs, we can see how the tariffs applied compare to theoretical optimal tariff. w Table 8. 2 shows various steel products along with their respective elasticities of export supply to the U. S. w We can compare the actual tariff to the optimal tariff to see where there were gains and where there were losses from the tariffs. w But what about retaliation? . . . 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 43 of 136

U. S. Tariffs on Steel Once Again APPLICATION Table 8. 2 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 44 of 136

U. S. Tariffs on Steel Once Again APPLICATION Table 8. 2 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 44 of 136

Import Quotas • On January 1, 2005, China was poised to become the world’s largest exporter of textiles and apparel. w On that date, the Multifibre Arrangement (MFA) was abolished. w Under the MFA, import quotas restricted the amount of nearly every textile and apparel product that was imported to Canada, Europe, and the U. S. w The quotas were to protect their own domestic firms producing those products. w The threat of import competition from China led the U. S. and Europe to negotiate new quotas with China. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 45 of 136

Import Quotas • On January 1, 2005, China was poised to become the world’s largest exporter of textiles and apparel. w On that date, the Multifibre Arrangement (MFA) was abolished. w Under the MFA, import quotas restricted the amount of nearly every textile and apparel product that was imported to Canada, Europe, and the U. S. w The quotas were to protect their own domestic firms producing those products. w The threat of import competition from China led the U. S. and Europe to negotiate new quotas with China. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 45 of 136

Import Quotas • Import Quota in a Small Country w Suppose the import quota of M 2

Import Quotas • Import Quota in a Small Country w Suppose the import quota of M 2

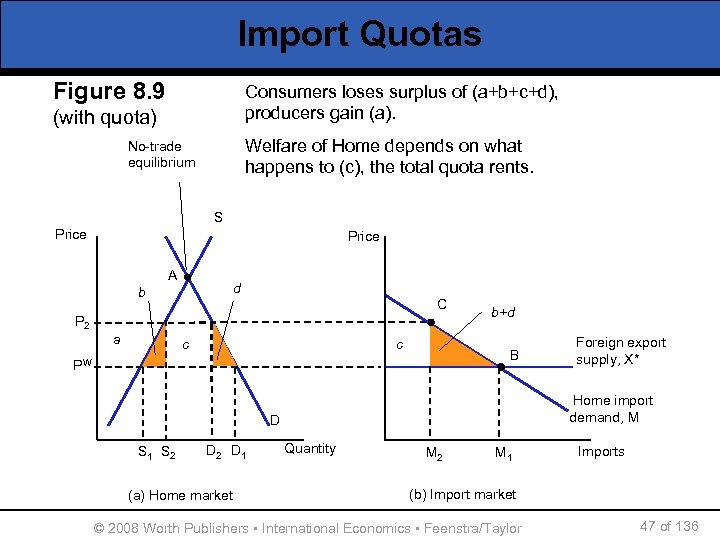

Import Quotas Figure 8. 9 Consumers new higher price (a+b+c+d), surplus of P The At the loses. Supply curve 2, Withnew Quota, the Export Always have a (a). Foreign export deadweight producers gain Home Supply increases to crosses the like the tariffat curve at supply becomes vertical loss of (b+d)Import Demandthe quota S a new 2 price and quantity onto Welfare, of Home dependsof imports quantity. Demand decreases what D 2 to imports fall quota happensand(c), the total to M 2 rents. (with quota) No-trade equilibrium S Price A d b C P 2 a c c b+d B PW Home import demand, M D S 1 S 2 D 1 (a) Home market Foreign export supply, X* Quantity M 2 M 1 Imports (b) Import market © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 47 of 136

Import Quotas Figure 8. 9 Consumers new higher price (a+b+c+d), surplus of P The At the loses. Supply curve 2, Withnew Quota, the Export Always have a (a). Foreign export deadweight producers gain Home Supply increases to crosses the like the tariffat curve at supply becomes vertical loss of (b+d)Import Demandthe quota S a new 2 price and quantity onto Welfare, of Home dependsof imports quantity. Demand decreases what D 2 to imports fall quota happensand(c), the total to M 2 rents. (with quota) No-trade equilibrium S Price A d b C P 2 a c c b+d B PW Home import demand, M D S 1 S 2 D 1 (a) Home market Foreign export supply, X* Quantity M 2 M 1 Imports (b) Import market © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 47 of 136

Import Quotas • There are four possible ways these rents can be allocated. 1. Giving the Quota to Home Firms: w Quota licenses can be given to Home firms § Permits to import the quantity allowed under the quota system. w The net effects on Home welfare due to the quota are then as follows: Fall in consumer surplus -(a+b+c+d) Rise in producer surplus +a Quota rents earned at Home +c Net effect on Home welfare: -(b+d) w w This is the same loss we saw with a tariff. (b+d) is still a deadweight loss associated with the quota. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 48 of 136

Import Quotas • There are four possible ways these rents can be allocated. 1. Giving the Quota to Home Firms: w Quota licenses can be given to Home firms § Permits to import the quantity allowed under the quota system. w The net effects on Home welfare due to the quota are then as follows: Fall in consumer surplus -(a+b+c+d) Rise in producer surplus +a Quota rents earned at Home +c Net effect on Home welfare: -(b+d) w w This is the same loss we saw with a tariff. (b+d) is still a deadweight loss associated with the quota. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 48 of 136

Import Quotas 2. Rent Seeking w Because of the gains associated with owning a quota license, firms have an incentive to engage in inefficient activities in order to obtain them. w How licenses are allocated matters. a. If licenses are allocated in proportion to each firm’s production, Home firms will likely produce more than they can sell just to obtain the import licenses for the following year. b. Firms might engage in bribery or other lobbying activities to obtain the licenses. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 49 of 136

Import Quotas 2. Rent Seeking w Because of the gains associated with owning a quota license, firms have an incentive to engage in inefficient activities in order to obtain them. w How licenses are allocated matters. a. If licenses are allocated in proportion to each firm’s production, Home firms will likely produce more than they can sell just to obtain the import licenses for the following year. b. Firms might engage in bribery or other lobbying activities to obtain the licenses. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 49 of 136

Import Quotas w Some suggest that the waste of resources devoted to rent seeking could be as large as the value of the rents themselves, c. w If rent seeking occurs, welfare loss of quota is: Fall in consumer surplus Rise in producer surplus Net effect on Home welfare: -(a+b+c+d) +a -(b+c+d) w This loss is larger than a tariff. w It is thought rent seeking is worse in developing countries. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 50 of 136

Import Quotas w Some suggest that the waste of resources devoted to rent seeking could be as large as the value of the rents themselves, c. w If rent seeking occurs, welfare loss of quota is: Fall in consumer surplus Rise in producer surplus Net effect on Home welfare: -(a+b+c+d) +a -(b+c+d) w This loss is larger than a tariff. w It is thought rent seeking is worse in developing countries. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 50 of 136

Import Quotas 3. Auctioning the Quota w The government of the importing country to auction off the quota licenses. w In a well-organized, competitive auction, the revenue collected should exactly equal the value of the rents. Fall in consumer surplus Rise in producer surplus Auction revenue earned at Home Net effect on Home welfare: w -(a+b+c+d) +a +c -(b+d) This is the same loss as the tariff. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 51 of 136

Import Quotas 3. Auctioning the Quota w The government of the importing country to auction off the quota licenses. w In a well-organized, competitive auction, the revenue collected should exactly equal the value of the rents. Fall in consumer surplus Rise in producer surplus Auction revenue earned at Home Net effect on Home welfare: w -(a+b+c+d) +a +c -(b+d) This is the same loss as the tariff. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 51 of 136

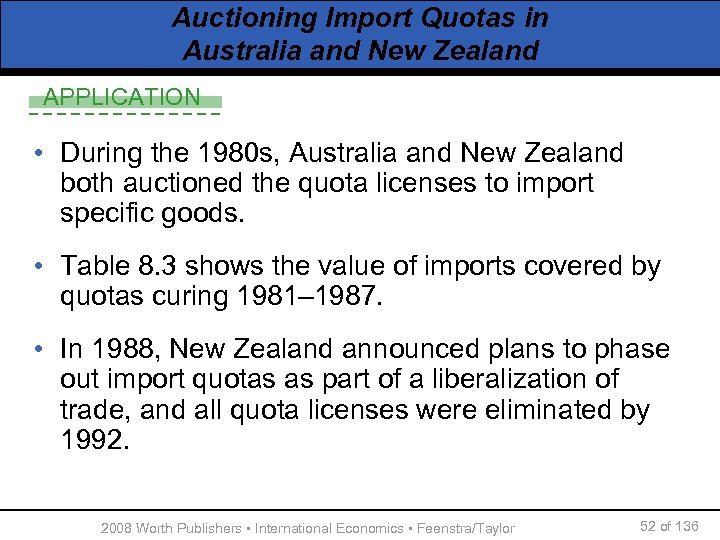

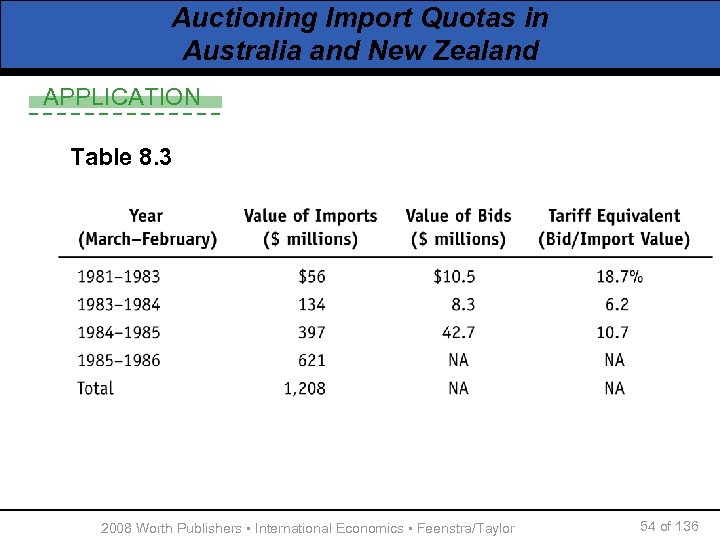

Auctioning Import Quotas in Australia and New Zealand APPLICATION • During the 1980 s, Australia and New Zealand both auctioned the quota licenses to import specific goods. • Table 8. 3 shows the value of imports covered by quotas curing 1981– 1987. • In 1988, New Zealand announced plans to phase out import quotas as part of a liberalization of trade, and all quota licenses were eliminated by 1992. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 52 of 136

Auctioning Import Quotas in Australia and New Zealand APPLICATION • During the 1980 s, Australia and New Zealand both auctioned the quota licenses to import specific goods. • Table 8. 3 shows the value of imports covered by quotas curing 1981– 1987. • In 1988, New Zealand announced plans to phase out import quotas as part of a liberalization of trade, and all quota licenses were eliminated by 1992. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 52 of 136

Auctioning Import Quotas in Australia and New Zealand APPLICATION • Table 8. 3 also shows the value of bids for the quota licenses. w These are estimates of rents. • If we take the ratio of the value of bids to the value of imports covered by the quota, we obtain an estimate of the tariff equivalent to the quota. w These are shown in the final column of table 8. 3 • Since there was no penalty from not following through, some firms decided not to purchase the licenses after all. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 53 of 136

Auctioning Import Quotas in Australia and New Zealand APPLICATION • Table 8. 3 also shows the value of bids for the quota licenses. w These are estimates of rents. • If we take the ratio of the value of bids to the value of imports covered by the quota, we obtain an estimate of the tariff equivalent to the quota. w These are shown in the final column of table 8. 3 • Since there was no penalty from not following through, some firms decided not to purchase the licenses after all. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 53 of 136

Auctioning Import Quotas in Australia and New Zealand APPLICATION Table 8. 3 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 54 of 136

Auctioning Import Quotas in Australia and New Zealand APPLICATION Table 8. 3 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 54 of 136

Auctioning Import Quotas in Australia and New Zealand APPLICATION • The government therefore did not collect all the winning bids as revenue. • For those that did buy their licenses, they could be resold and some were at much higher prices. • This makes it appear that the government was not collecting all of the rents in area c. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 55 of 136

Auctioning Import Quotas in Australia and New Zealand APPLICATION • The government therefore did not collect all the winning bids as revenue. • For those that did buy their licenses, they could be resold and some were at much higher prices. • This makes it appear that the government was not collecting all of the rents in area c. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 55 of 136

Import Quotas 4. “Voluntary” Export Restraint w The importing country can give authority for implementing the quota to the exporting government. w This is often called a “voluntary” export restraint (VER) or a “voluntary” restraint agreement (VRA). w In the 1980 s the U. S. used this type of arrangement to restrict imports of Japanese automobiles. § The Japanese government told each Japanese firm how much it could export to the U. S. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 56 of 136

Import Quotas 4. “Voluntary” Export Restraint w The importing country can give authority for implementing the quota to the exporting government. w This is often called a “voluntary” export restraint (VER) or a “voluntary” restraint agreement (VRA). w In the 1980 s the U. S. used this type of arrangement to restrict imports of Japanese automobiles. § The Japanese government told each Japanese firm how much it could export to the U. S. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 56 of 136

Import Quotas • With VERs, quota rents are earned by foreign producers, making Home welfare: Fall in consumer surplus Rise in producer surplus Net effect on Home welfare: -(a+b+c+d) +a -(b+c+d) • This is a higher net loss than with a tariff. • Why would an importing country do this? w It is typically political—the exporting country is less likely to retaliate since they gain the area c. w This can often avoid a tariff or quota war. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 57 of 136

Import Quotas • With VERs, quota rents are earned by foreign producers, making Home welfare: Fall in consumer surplus Rise in producer surplus Net effect on Home welfare: -(a+b+c+d) +a -(b+c+d) • This is a higher net loss than with a tariff. • Why would an importing country do this? w It is typically political—the exporting country is less likely to retaliate since they gain the area c. w This can often avoid a tariff or quota war. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 57 of 136

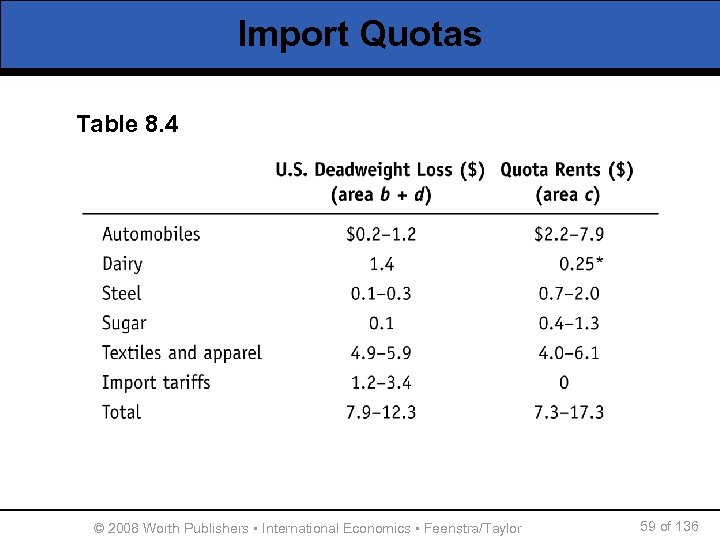

Import Quotas • Costs of Import Quotas in the U. S. w Table 8. 4 presents some estimates of Home deadweight losses and quota rents for some major U. S. quotas in the 1980’s. w In all cases except Dairy, the rents were earned by Foreign exporters. w Adding up the costs in the table, the total U. S. deadweight loss due to these quotas ranged from $8– $12 billion annually. w Quota rents transferred another $7–$17 billion to foreigners. w Some, but not all, of these costs are relevant today since many of the quotas are no longer in place. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 58 of 136

Import Quotas • Costs of Import Quotas in the U. S. w Table 8. 4 presents some estimates of Home deadweight losses and quota rents for some major U. S. quotas in the 1980’s. w In all cases except Dairy, the rents were earned by Foreign exporters. w Adding up the costs in the table, the total U. S. deadweight loss due to these quotas ranged from $8– $12 billion annually. w Quota rents transferred another $7–$17 billion to foreigners. w Some, but not all, of these costs are relevant today since many of the quotas are no longer in place. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 58 of 136

Import Quotas Table 8. 4 © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 59 of 136

Import Quotas Table 8. 4 © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 59 of 136

China and the Multifibre Arrangement APPLICATION • One of the principles of GATT was that countries should not use quotas to restrict imports. • The MFA was a major exception to that which allowed the industrialized countries to restrict imports of textile and apparel products from the developing countries. • Organized under GATT, importing countries could join the MFA and arrange quotas bilaterally or unilaterally. • Under the Uruguay round of WTO, developing countries were able to negotiate an end to this system of import quotas. • Some developing countries and large producers in importing countries were concerned with the potential of Chinese exports on their economies. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 60 of 136

China and the Multifibre Arrangement APPLICATION • One of the principles of GATT was that countries should not use quotas to restrict imports. • The MFA was a major exception to that which allowed the industrialized countries to restrict imports of textile and apparel products from the developing countries. • Organized under GATT, importing countries could join the MFA and arrange quotas bilaterally or unilaterally. • Under the Uruguay round of WTO, developing countries were able to negotiate an end to this system of import quotas. • Some developing countries and large producers in importing countries were concerned with the potential of Chinese exports on their economies. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 60 of 136

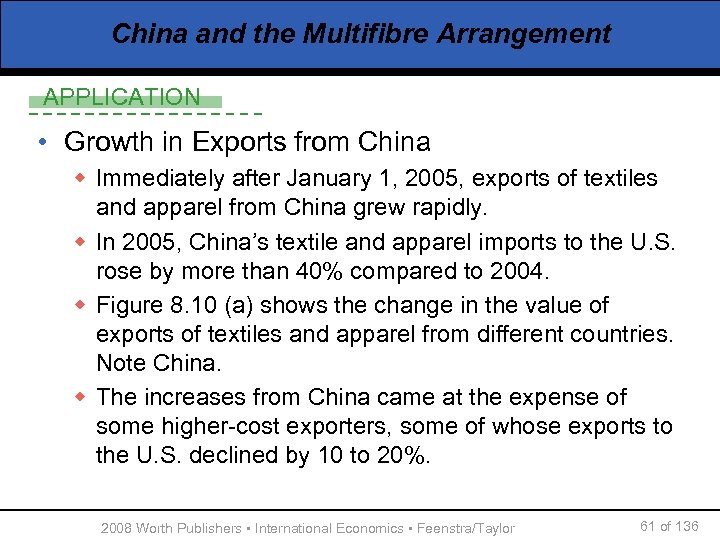

China and the Multifibre Arrangement APPLICATION • Growth in Exports from China w Immediately after January 1, 2005, exports of textiles and apparel from China grew rapidly. w In 2005, China’s textile and apparel imports to the U. S. rose by more than 40% compared to 2004. w Figure 8. 10 (a) shows the change in the value of exports of textiles and apparel from different countries. Note China. w The increases from China came at the expense of some higher-cost exporters, some of whose exports to the U. S. declined by 10 to 20%. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 61 of 136

China and the Multifibre Arrangement APPLICATION • Growth in Exports from China w Immediately after January 1, 2005, exports of textiles and apparel from China grew rapidly. w In 2005, China’s textile and apparel imports to the U. S. rose by more than 40% compared to 2004. w Figure 8. 10 (a) shows the change in the value of exports of textiles and apparel from different countries. Note China. w The increases from China came at the expense of some higher-cost exporters, some of whose exports to the U. S. declined by 10 to 20%. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 61 of 136

China and the Multifibre Arrangement APPLICATION Figure 8. 10 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 62 of 136

China and the Multifibre Arrangement APPLICATION Figure 8. 10 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 62 of 136

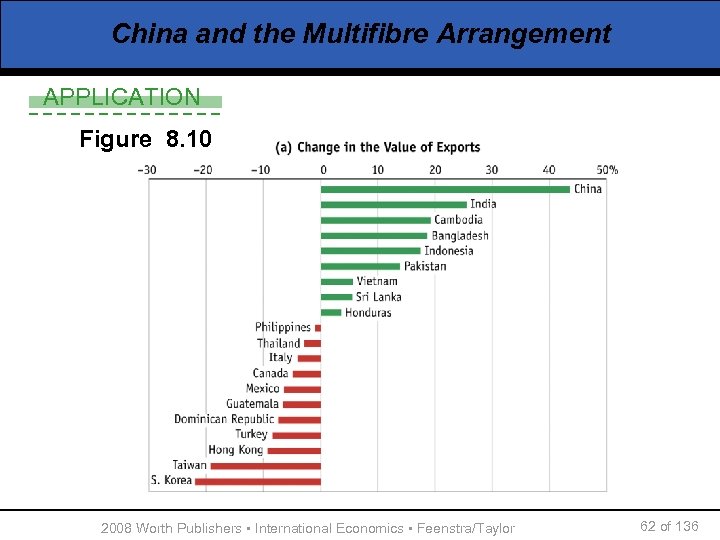

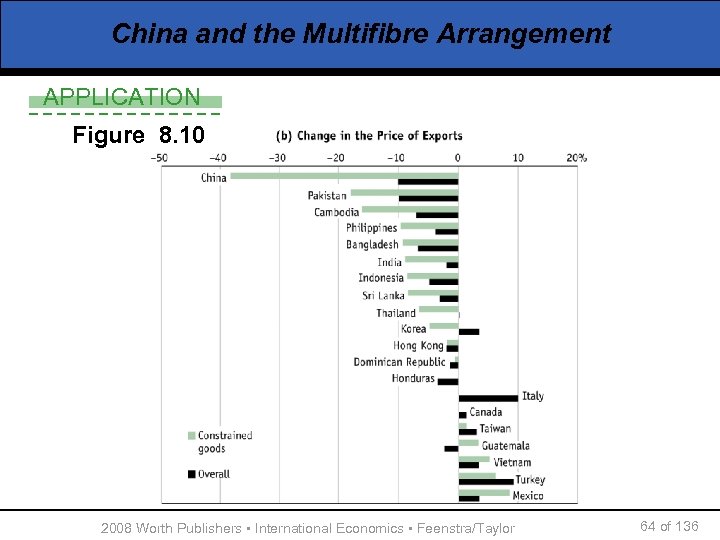

China and the Multifibre Arrangement APPLICATION • Panel (b) of figure 8. 10 shows the percentage change in the prices of textiles and apparel products from each country, depending on whether the products were subject to the MFA quota before January 1, 2005, or not. • China had the largest drop in the prices from 2004 to 2005. • Many other countries had a substantial fall in their prices due to the end of the MFA quota. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 63 of 136

China and the Multifibre Arrangement APPLICATION • Panel (b) of figure 8. 10 shows the percentage change in the prices of textiles and apparel products from each country, depending on whether the products were subject to the MFA quota before January 1, 2005, or not. • China had the largest drop in the prices from 2004 to 2005. • Many other countries had a substantial fall in their prices due to the end of the MFA quota. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 63 of 136

China and the Multifibre Arrangement APPLICATION Figure 8. 10 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 64 of 136

China and the Multifibre Arrangement APPLICATION Figure 8. 10 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 64 of 136

China and the Multifibre Arrangement APPLICATION • Welfare Cost of the MFA w Given the drop in prices in 2005, it is possible to estimate the welfare loss due to the MFA. w Using the price drops from figure 8. 10, the welfare loss for the U. S. (b+c+d), is estimated at $6. 5 to $16. 2 billion in 2005 from the MFA. w Averaging out all losses and dividing among households gives an estimate of $100 per household, or 7% of total annual spending on apparel. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 65 of 136

China and the Multifibre Arrangement APPLICATION • Welfare Cost of the MFA w Given the drop in prices in 2005, it is possible to estimate the welfare loss due to the MFA. w Using the price drops from figure 8. 10, the welfare loss for the U. S. (b+c+d), is estimated at $6. 5 to $16. 2 billion in 2005 from the MFA. w Averaging out all losses and dividing among households gives an estimate of $100 per household, or 7% of total annual spending on apparel. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 65 of 136

China and the Multifibre Arrangement APPLICATION • Import Quality w Quotas are set on the quantity, not the quality of items imported. w Selling a higher value good for the same quantity will still meet the quota limit but will bring more money back home. § Incentive to export higher quality products. w Prices dropped the most for the lower- priced items. § An inexpensive T-shirt had a greater drop in price than a more expensively priced item. w U. S. demand shifted towards the lower-priced items imported from China: there was “quality downgrading” in the exports from China. w When a quota like the MFA is applied, there is an effect on quality. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 66 of 136

China and the Multifibre Arrangement APPLICATION • Import Quality w Quotas are set on the quantity, not the quality of items imported. w Selling a higher value good for the same quantity will still meet the quota limit but will bring more money back home. § Incentive to export higher quality products. w Prices dropped the most for the lower- priced items. § An inexpensive T-shirt had a greater drop in price than a more expensively priced item. w U. S. demand shifted towards the lower-priced items imported from China: there was “quality downgrading” in the exports from China. w When a quota like the MFA is applied, there is an effect on quality. 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 66 of 136