f1f352f526145bb030fbb2302436a52c.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 58

6. 0 PROLOG LAB Using visual PROLOG version 5. 2 Example 1: Assume the following “likes” facts knowledge base likes (ali, football). likes (ali, tennis). likes (ahmad, handball). likes (samir, swimming). likes (khaled, horseriding).

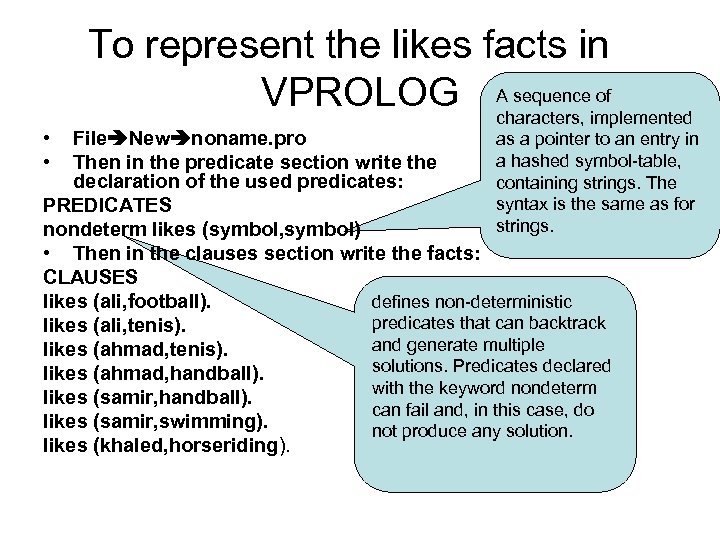

• • To represent the likes facts in of VPROLOG A sequenceimplemented characters, File New noname. pro as a pointer to an entry in a hashed symbol-table, Then in the predicate section write the declaration of the used predicates: containing strings. The syntax is the same as for PREDICATES strings. nondeterm likes (symbol, symbol) • Then in the clauses section write the facts: CLAUSES defines non-deterministic likes (ali, football). predicates that can backtrack likes (ali, tenis). and generate multiple likes (ahmad, tenis). solutions. Predicates declared likes (ahmad, handball). with the keyword nondeterm likes (samir, handball). can fail and, in this case, do likes (samir, swimming). not produce any solution. likes (khaled, horseriding).

1. Queries as goals in PROLOG • To supply a query in PROLOG put it in the goal section as follows: GOAL likes (ali, football). • Then press Cntrl+G The output will be Yes or No for concrete questions 1. Concrete questions: (queries without variables) Example: GOAL likes(samir, handball). Yes Likes (samir, football). No

2. Queries with variables • To know all sports that ali likes: likes(ali, What). • To know which person likes teniss likes (Who, tenis). • To know who likes what (i. e all likes facts) likes (Who, What)

3. Compound queries with one variable 1. To list persons who likes tennis and football, the goal will be likes( Person, tennis ), likes (Person, football). Person=ali 2. To list games liked by ali and ahmad likes (ali, Game), likes (ahmad, Game). Game=tennis

4 -Compound queries with multiple variables • To find persons who like more than one game: likes(Person, G 1), likes (Person, G 2), G 1<>G 2. • To find games liked by more than one person: likes (P 1, Game), likes(P 2, Game), P 1<>P 2.

5. Facts containing variables • Assume we add the drinks facts to the likes database as follows: PREDICATES drinks(symbol, symbol) CLAUSES drinks(ali, pepsi). drinks (samir, lemonada). drinks (ahmad, milk). • To add the fact that all persons drink water: drinks (Everyone, water). • If we put a goal like: drinks (samy, water). The answer will be: drinks (ahmad, water). yes

6. Rules • Rules are used to infer new facts from existing ones. • A rule consists of two parts: head and body separated by the symbol (: -). • To represent the rule that express the facts that two persons are friends if they both like the same game: Rule’s symbol friends( P 1, P 2): likes (P 1, G), likes (P 2, G), P 1<>P 2. The head of the rule The body of the rule

7. Backtracking in PROLOG • For PROLOG to answer the query : friends (ali, P 2). PROLOG will do the following matches and backtracking to the friends rule: P 1 G P 2 P 1<>P 2 friends (ali, P 2) ali football ali false fail ali tennis ahmad true succeed

8. The domains section in VPROLOG • It is used to define domains other than the builtin ones, also to give suitable meanings to predicate arguments. • For example to express the likes relation: likes(person, game) Person and game are unknown domains (error) We should first declare person in the domains section as follows: This declaration will allow prolog to detect type errors. domains Example: the query person, game= symbol likes(X, Y), likes(Y, Z) will result in a type error, because Y will be predicates matched to a game constant and can not likes (person, game) replace a person variable in the second sub goal.

9. Built-in domains domain short ushort long Number of bits 16 bits 32 bits range -32768. . 32767 0. . 65535 -2147483648. . 2147483648 ulong 32 bits 0. . 4294967295 integer 16 bit platform 32 bit platform byte word dword 8 bits 16 bit 32 bit -32768. . 32767 -2147483648. . 2147483648 0. . 255 0. . 65535 0. . 4294967295

10. Basic standard domains Domain description char 8 -bits surrounded by single quotation: ‘a’ Floating point number: 42705, 9999, 86. 72, 911. 98 e 237 Range 1 e-307. . 1 e+308 Pointer to 0 -terminated byte arraey telephone, “Telephone”, t 2, ”T 2” As strings but implemented as a pointer to hashed symbol table faster than strings real string symbol

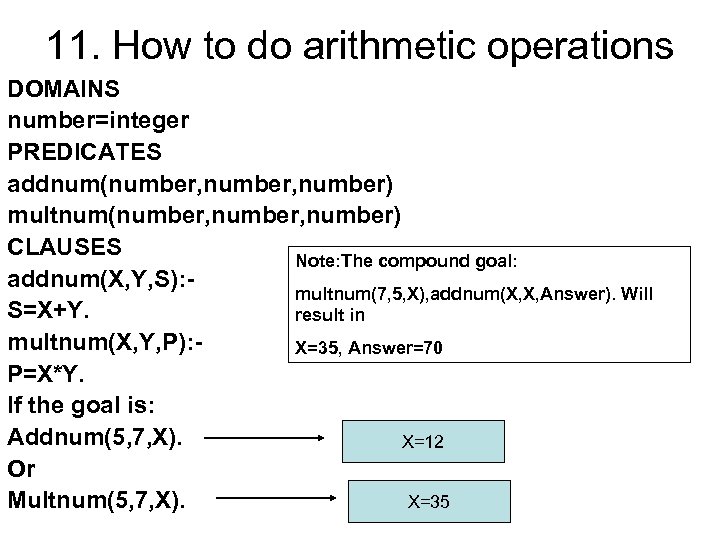

11. How to do arithmetic operations DOMAINS number=integer PREDICATES addnum(number, number) multnum(number, number) CLAUSES Note: The compound goal: addnum(X, Y, S): multnum(7, 5, X), addnum(X, X, Answer). Will S=X+Y. result in multnum(X, Y, P): X=35, Answer=70 P=X*Y. If the goal is: Addnum(5, 7, X). X=12 Or X=35 Multnum(5, 7, X).

12. More programs to test domains • The isletter(X) predicate gives yes if X is a letter: PREDICATES isletter(char) CLAUSES isletter(Ch): - To test this program, give it the following goals: aisletter(‘x’). yes ‘a’<=Ch, bisletter(‘ 2’). no cisletter(“hallo”). type error Ch<=‘z’. disletter(a). Type error isletter(Ch): - eisletter(X) free variable message ‘A’<=Ch, Ch<=‘Z’.

13. Multiple arity predicates overloading • The arity of a predicate is the number of arguments that it takes. • You can have two predicates with the same name but with different arities. • You must group different arity versions of a given predicate name in both the predicate and clauses sections. • The different arities predicates are treated as different predicates.

14. Example: for multiple arity predicates DOMAINS person=symbol PREDICATES nondeterm father (person) nondeterm father (person, person) CLAUSES father (Man): father (Man, _). father (ali, ahmad). father (samy, khaled). Anonymous variable can match anything. A person is said to be a father if he is a father of any one.

15. A complete expert system that decides how a person can buy a car. • Assuming – A person is described by the two relations: salary (person, money) savings (person, money) – A car for sale is described by the two relations: cash (cartype, money) takseet(cartype, money)

• A person can buy a car -with cash money if one third of his savings is greater or equal to the cash price of the car. -with takseet if one third of his salary is greater or equal to the price of the car in case of cash divided by 30. - If the person can buy a car using cash or takseet the system will advice him to buy with cash

The VPROLOG program DOMAINS person, car =symbol money=real way=string PREDICATES salary (person, money) savings (person, money) cash (car, money) takseet (car, money) canbuy (person, car, way) howcanbuy (person, car, way)

CLAUSES cash (cressida, 15000). cash (camri, 55000). cash (caprise 82, 5000). cash (caprise 90, 8000). cash (landcruizer 2003, 100000). takseet (Car, TPrice): cash (Car, Price), TPrice=Price*1. 2. canbuy ( Person, Car, “cash”): savings (Person, M), cash( Car, N), M/3>=N. canbuy ( Person, Car, “takseet”): salary (Person, M), takseet(Car, T), M/3>=T/30.

OR howcanbuy (Person, Car, Way): canbuy (Person, Car, Way), Way="cash"; canbuy (Person, Car, Way), Way="takseet", NOT(canbuy (Person, Car, "cash")). Should be placed around expressions which include only constants and /or bounded variables. These variables will be bounded before reaching the “not” expression containing them

16. Controlling Backtracking • The fail Predicate: • V Prolog begins backtracking when a call fails. • The fail predicate is used to force backtracking. • The following program uses fail to get all solutions. • Without fail we will get only one solution. DOMAINS name=symbol PREDICATES nondeterm father(name, name) everybody CLAUSES father (ali, salem). father (ahmad, ibrahim). father (ahmad, zaynab). everybody: father (X, Y), write (X, ” is ” , Y, ”’s fathern” ), fail. To make the goal everybody. succeed at the end GOAL everybody.

• Preventing backtracking by the cut (!) • It is impossible to backtrack across a cut. • Green cut: it is a cut used to prevent solutions which does not give meaningful solutions. • Red cut : it is a cut used to prevent alternate subgoals. • Example: to prevent backtracking to previous subgoals: Only first solution to a and b is r 1: - a, b, !, c. considered with many solutions for c r 1: -d. this clause for r 1 will not be considered if a solution is found in the above rule.

17. Highway Map modelling and recursive rules • To represent the shown map we use the predicate link ( node, distance) • To find a path from s to d – get it from mentioned facts : path (S, D, TDist): -link (S, D, TDist). – Or find a node x which has a link from S to X and a path from X to D Total distance as follows: path (S, D, TDist): link (S, X, DS 1), path (X, D, DS 2), TDist=DS 1+DS 2. a 4 b 2 c 5 6 5 d 3 link(a, b, 4). link (a, c, 2). link (b, g, 5). link (c , g, 6). link (c, d, 5). link (d, g, 3). g

DOMAINS The complete path distance finder program node=symbol distance= integer PREDICATES nondeterm link (node, distance) nondeterm path ( node, distance) CLAUSES link(a, b, 4). link (a, c, 2). link (b, g, 5). Facts that model the road map link (c , g, 6). link (c, d, 5). Recursive link (d, g, 3). rule path (S, D, TDist): -link (S, D, TDist). path (S, D, TDist): link (S, X, TD 1 ), path (X, D, TD 2), TDist=TD 1+TD 2. GOAL Total. Distance=9 output path (a, g, Total. Distance). Total. Distance=8 Total. Distance=10 3 Solutions

18. Rules which behave like procedures greet: • A rule that when its write(“ASalamo Alykom”), n 1. head is found in a goal will print something. PREDICATES nondeterm action (integer) • Rules used like CLAUSES case statements: action(1): - nl, write (“N=1”), nl. action(2): - nl, write (“N=2”), nl. action(3): - nl, write (“N=3”), nl. Only rules with action (N): - nl, matching arguments N<>1, N<>2, N<>3, write (“N=? ”), nl. will be executed, GOAL write (“Type a number 1 ->3”), readint (N) , others will be testedaction(N). but will fail.

• Since rules that PREDICATES has unmatched nondeterm action (integer) arguments will CLAUSES be tested and action(1): -!, nl, write (“N=1”), nl. will fail. This will action(2): - !, nl, write (“N=2”), nl. slow the action(3): - !, nl, write (“N=3”), nl. program. To speed up the action (_): - nl, system use the , write (“unknown number ? ”), nl. cut as shown. GOAL write (“Type a number 1 ->3”), readint (N) , action(N). • If you want to test a range x>5 and <9 place the cut after the test sub goals. Action(X): - X>5, X<9, !, write(“ 5<N<9”), n 1.

To make a rule return a value • To define a rule which classifies a number either positive, negative or zero: PREDICATES nondeterm classify (integer, symbol). CLAUSES classify( X, pos): - X>0. What carries classify( X, neg): - X<0. the returned result classify( X, zero): - X=0. Goal What=pos Classify ( 5, What) What=nig Classify (-4, What) error Classify (X, What)

19. Compound data objects • Compound data objects allow you to treat several pieces of information as a single item (like structures in c, c+, or c#). • Example: to represent a date object: called : functor DOMAINS date_cmp= date(string, unsigned) Hence in a rule or goal you can write: . . , D=date(“March”, 1, 1960). Here D will be treated as a single item.

• The arguments of a compound object can themselves be compound: Example : to represent the information for the birthday of a person: BIRTHDAY PERSON Ahamd Ali DATE 1 March 1960 DOMAINS birthday= birthday (person, date) person = person (name, name) date= date (day, month, year) name, month =string day, year= unsigned birthday(person(“ahmad”, ”ali”), date(1, ”march”, 1960))

19. 1 A family birthday program DOMAINS person = person (name, name) Compound birthdate= bdate (day, month, year) objects name, month =string day, year= unsigned PREDICATES nondeterm birthday (person, bdate) CLAUSES birthday(person("amin", "mohamad"), bdate(1, "March", 1960)). birthday(person("mohamd", "amin"), bdate(11, "Jan", 1988)). birthday(person("abdo", "mohamad"), bdate(11, "Oct", 1964)). birthday(person("ali", "mohamad"), bdate(1, "Feb", 1950)). birthday(person("suzan", "antar"), bdate(1, "March", 1950)). GOAL Lists all birthday’s person, and date objects %birthday(X, Y). Lists persons born on March %birthday(X, date(_, "March", _)). %birthday(person(X, "mohamad"), bdate(_, _, Y)). Lists persons whose second name is “mohamd” with year of birth

19. 2 Using system date DOMAINS person = person (name, name) bdate= bdate (day, month, year) name=string day , month, year= unsigned PREDICATES nondeterm birthday (person, bdate) get_birth_thismonth testnow (unsigned, bdate) write_person(person) CLAUSES birthday(person("amin", "mohamad"), bdate(1, 3, 1960)). birthday(person("mohamd", "amin"), bdate(11, 5, 1988)). birthday(person("abdo", "mohamad"), bdate(11, 5, 1964)). birthday(person("ali", "mohamad"), bdate(1, 6, 1950)). birthday(person("suzan", "antar"), bdate(1, 3, 1982)). get_birth_thismonth: - date (_, Thism , _), write ( “now month is", Thism), nl, birthday (P, D), testnow(Thism, D), write_person(P), fail. get_birth_thismonth: -write (“Press any key to continue"), nl, readchar(_). testnow(TM, bdate (_, BM, _)): - TM=BM. write_person(Fn, Ln)): -write(" ", Fn, "tt ", Ln), nl. GOAL get_birth_thismonth.

19. 3 Using alternatives in domain declaration • Assume we want to declare the following statements: – Ali owns a 3 -floar house – Ali owns a 4 -door car – Ali owns a 3. 2 Ghz computer – To define a thing to be either house, car, or computer: DOMAINS thing= house( nofloars); car (nodoors); computer(ghertz) nofloars, nodoors=integer Use or(; ) to separate ghertz=real alternatives. person= person(fname, lname) fname, lname=symbol goal owns (P, X). PREDICATES 2 solutions nondeterm owns(person, thing) CLAUSES owns( person(mohamad, ali), house(3)). owns(person(mohamd, ali), computer(3. 2)).

19. 4 Lists • To declare the subjects a teacher might teach: PREDICATES teacher (symbol, symbol) CLAUSES teacher (ahmad, ezz, cs 101). teacher (ahmad, ezz, cs 332). teacher (amin, mohamad, cs 435). teacher (amin, mohamad, cs 204). teacher (amin, mohamad, cs 212). teacher (reda, salama, cs 416). teacher (reda, salama, cs 221). Here, the teacher name is repeated many times. We need a variable length data structure that holds all subjects that a teacher can teach Solution: use a list data Solution use a list data structure for the subject DOMAINS subject=symbol * PREDICATES teacher (symbol, subject) CLAUSES teacher(ahmad, ezz, [cs 101, cs 332] ) teacher (amin, mohamad, [cs 204, cs 435, cs 212] ). teacher (reda, salama, [cs 416, cs 221] ).

20. Repetition and Recursion • Repetition can be expressed in PROLOG in procedures and data structures. • Two kinds of repetition exist in PROLOG: Backtracking: search for multiple solutions When a sub goal fails, PROLOG returns to the most recent subgoal that has an untried alternative. Using the fail predicate as the end of repeated subgoals we enforce PROLOG to repeat executing different alternatives of some subgoals. Recursion: a procedure calls itself Normal recursion: Takes a lot of memory and time Tail recursion: fast and less memory Compiled into iterative loops in M/C language

20. 1 Repetition using backtracking • Example: Using fail to print all countries: PREDICATES nondeterm country (symbol) print_countries CLAUSES country (“Egypt”). country (“Saudi. Arabia”). country ( “Seria”). country (“Sudan”). print_countries: - country(X), write(X), nl, fail. print_countries. GOAL print_countries. country(X) write (X) nl fail print_co untries X=“Egypt” ok ok fail X=“Saudi. A ok rabia” ok fail X=“Seria” ok ok fail X=“Sudan” ok ok fail

• To do pre-actions (before the loop )or post-actions (after the loop), write different versions of the same predicate. • • • • 20. 1. 2 Pre and post actions country(X) write(X, ” and “) fail Print_cou ntries PREDICATES X=“Egypt” Ok fail nondeterm country (symbol) nondeterm print_countries CLAUSES X=“Saudi. Arabia” Ok fail country ("Egypt"). country ("Saudi. Arabia"). country ( "Seria"). X=“Seria” Ok fail country ("Sudan"). print_countries: write("Some Arabic countries are"), nl, fail. X=“Sudan” Ok fail print_countries: country(X), write(X, " and "), fail. print_countries: Pre-action nl, write("there are others"), Some Arabic countries are nl. Egypt and Saudi. Arabia and Seria and Sudan GOAL There are others Print_countries. Main-action Post-action

20. 2 Implementing backtracking with loops • The following repeat predicate tricks PROLOG and makes it think it has infinite solutions: 1 st repeat. solution 2 nd repeat: - repeat. solution The shown program uses repeat to keep accepting a character and printing it until it is CR PREDICATES repeat typewriter CLAUSES repeat. Nth solution (N+1)th solution repeat: - repeat. trypewriter: repeat, readchar(C), Multiple solutions attract backtracking when fail occurs write(C) , C=‘r’, !. /* if CR then cut

20. 3 Recursive procedures • To find the factorial of a number N : FACT(N) IF N=1 then FCT(N)=1 Else FACT(N)=N* FACT(N-1) • Using PROLOG, the factorial is implemented with two versions of the factorial rule as shown here. PREDICATES factorial (unsigned, real) CLAUSES factorial (1, 1): -!. factorial (N, Fact. N): M=N-1, factorial (M, Fact. M), Fact. N=N*Fact. M. Goal factorial (5, F). F=120 1 Solution

• • 20. 4 Tail Recursion Occurs when a procedure calls itself as the last step. Occurs in PROLOG , when 1. The call is the very last subgoal in a clause. 2. 3. 4. • No backtracking points exist before this call. The recursive predicate does not return a value. Only one version of this predicate exists. Example: count (N): write(N), nl, New. N=N+1, count (New. N). GOAL count(0). You can use a cut(!) before the last call to be sure of (2). No alternative (2)Noalternative solutions exist No alternative solutions backtracking points here no here solutions here (3)N is bound to a constant value and no other free variable no return value (1) Last call no need to save state of the previous call stack is free no extra memory is needed small memory and fast due to no need to push state Write numbers from 0 to infinity ( will get unexpected values due to overflow)

20. 5 Using arguments as loop variables • To implement factorial with iterative procedure using C-language: long fact; long p=1; unsigned i=1; while(i<=n) { p=p*i; i=i+1; } fact=p; PREDICATES factorial (unsigned, long) factorial_r(unsigned, long, unsigned, long) CLAUSES factorial (N, Fact. N): - Initialize arguments I, P factorial_r(N, Fact. N, 1, 1). factorial_r( N, Fact. N, I, P): I<=N, !, New. P=P*I, New. I=I+1, Test end condition to go to other version if not satisfied. To prevent backtracking and to allow tail recursion. factorial_r(N, Fact. N, New. I, New. P). factorial_r(N, Fact. N , I , P): - I>N, Fact. N=P.

21. Lists and Recursion • List processing allows handling objects that contain an arbitrary number of elements. • A list is an object that contains an arbitrary number of other objects. • A list that contains the numbers 1, 2 and 3 is written as [1, 2, 3]. • Each item contained in a list is know as an element. • To declare the domain of a list of integers: – Domains – intlist= integer * Means list of integers Could be any other name ( ilist, il, …)

• The elements of a list must be of a single domain. • To define a list of mixed types use compound objects as follows: • Domains – elementlist= element * – element=ie (integer); re ( real); se (string) • A list consists of two parts: – The head : the first element of the list – The tail : a list of the remaining elements. • Example: if l=[a, b, c] the head is a and the tail is [b, c]. The Tail The Headt

• If you remove the first element from the tail of the list enough times, you get down to the empty list ([ ]). • The empty list can not be broken into head and tail. • A list has a tree structure like compound objects. • Example: the tree structure of list [a, b, c, d] is drawn as shown in the figure. list a Note : the one element list [a] is not as the element a since [a] is really the compound data structure shown here [a] a [] b list c list d []

21. 1 List processing • Prolog allows you to treat the head and tail explicitly. You can separate the list head and tail using the vertical bar (|). • Example : • [a, b, c ] ≡[a | [b, c ] ] ≡[a | [b| [c ] ] ] ≡[a | [b| [c| [] ] ≡[a , b| [c ] ]

• 21. 2 List unification: the following table gives examples of list unification: list 1 list 2 Variable binding [X, Y, Z] [ book, ball, pen ] X=book, Y=ball, Z=pen [7] [X|Y] X=7, Y=[ ] [1, 2, 3, 4] [X, Y|Z ] X=1, Y=2, Z=[3, 4] [1, 2] [3|X] fail

• 21. 3 Using lists – Since a list is really a recursive compound data structure, you need recursive algorithms to process it. – Such an algorithm is usually composed of two clauses: - DOMAINS list= integer * PREDICATES write_a_list( list ) Do nothing CLAUSES but report success. write_a_list([ ]). • One to deal with empty list. T=[ ] write_a_list ( [ H | T ] ): • The other deals with ordinary list (having head Write the write(H), and tail). head nl, • Example: the shown program writes the elements of an integer list. write_a_list( T). Write the Tail list GOAL write_a_list([ 1, 2, 3]).

21. 4 Counting list elements • • Two logical rules are used to determine the length of a list 1. The length of [ ] is 0. 2. The length of the list [X|T] is 1+the length of T. DOMAINS list= integer * PREDICATES length_of ( list, integer) CLAUSES length_of ( [], 0). T=[ ] Length_of ( [ H | T ], L ): The shown Prolog length_of ( T , M ), program counts L=M+1. the number of L=3 GOAL elements of a list length_of([ 1, 2, 3], L). of integers (can be used for any type). Homework: modify the length program to calculate the sum of all elements of a list

21. 5 Modifying the list • The following program adds 1 to each element of a list L 1 by making another list L 2: – If L 1 is [ ] then L 2=[ ] – If L 1=[H 1|T 1] assuming L 2=[H 2|T 2] then • H 2=H 1+1. • Add 1 to T 1 by the same way DOMAINS list= integer * PREDICATES add 1 ( list, list) CLAUSES add 1 ( [], []). add 1 ( [ H 1 | T 1 ], [H 2|T 2] ): H 2=H 1+1, add 1( T 1, T 2). GOAL add 1( [ 1, 2, 3], L ). L=[ 2, 3, 4]

21. 6 Removing Elements from a list • The following program removes negative elements from a list L 1 by making another list L 2 that contains non negative numbers of L 1 : – If L 1 is [ ] then L 2=[ ] – If L 1=[H 1|T 1] and H 1<0 then neglect H 1 and process T 1 – Else make head of L 2 H 2=H 1 and Repeat for T 1. DOMAINS list= integer * PREDICATES discard_NG ( list, list) CLAUSES discard_NG ( [], []). discard_NG ( [ H 1 | T 1 ], L 2 ): H 1<0, !, discard_NG(T 1, L 2). discard_NG ( [ H 1 | T 1 ], [H 1|T 2] ): discard_NG(T 1, T 2). GOAL discard_NG( [ 1, -2, 3], L ). L=[ 1, 3]

21. 7 List Membership • To detect that an element E is in a list L: – If L=[H|T] and E=H then report success Else – search for E in T Try the goal member (X, [samy, salem, ali]). What happens if we put a cut at the first clause as follows: member (E , [E | _ ] ): - !. DOMAINS namelist= name* name= symbol PREDICATES nondeterm member (name, namelist) CLAUSES member (E , [E | _ ] ). member (E, [ _ | T]): member (E, T). GOAL member (ali, [samy, salem, ali]). Yes

21. 8 Appending one list to another • To append L 1 to L 2 we get the result in L 3 as follows • Append (L 1, L 2, L 3): – If L 1=[ ] then L 3=L 2. – Else – Make H 3=H 1 and – make T 3 =T 1 +L 2 Try the goals: 1 -append ([1, 2], [3], L), append( L, L, LF). 2 -append ( L, [5, 6], [1, 2, 3, 5, 6]). DOMAINS intlist= integer* PREDICATES append (intlist, intlist) CLAUSES append ([], L 2 ). append ([H | T 1], L 2, [H|T 3] ): append (T 1, L 2, T 3). GOAL append([1, 2, 3], [5, 6], L). L= [1, 2, 3, 5, 6].

![21. 9 Tracing the append goal append([1, 2, 3], [5, 6], L). L =[1, 21. 9 Tracing the append goal append([1, 2, 3], [5, 6], L). L =[1,](https://present5.com/presentation/f1f352f526145bb030fbb2302436a52c/image-53.jpg)

21. 9 Tracing the append goal append([1, 2, 3], [5, 6], L). L =[1, 2, 3, 5, 6] DOMAINS intlist= integer* append ([1 | [2, 3] ], [5, 6], [1|T 3] ): append ([2, 3 ], [5, 6], [T 3] ): - PREDICATES T 3 =[2, 3, 5, 6] append (intlist, intlist) CLAUSES append ([2 | [3] ], [5, 6], [2|T 3’] ): append ([3 ], [5, 6], T 3’ ): - append ([], L 2 ). T 3’ =[3, 5, 6] append ([H | T 1], L 2, [H|T 3] ): append (T 1, L 2, T 3). GOAL append ([3 | [ ] ], [5, 6], [3|T 3’’] ): append ([ ], [5, 6], T 3’’ ). T 3’’ =[5, 6] append([1, 2, 3], [5, 6], L). L= [1, 2, 3, 5, 6].

22 VPROLOG facts Section • The facts section is declared to allow a programmer to add or remove facts at run time. • Facts declared in fact section are kept in tables to allow modification, while normal facts are compiled into binary code for speed optimization. 1. To declare a fact in a fact section: • DOMAINS Name of this • person=string fact section • FACTS -up • father (person, person) • CLAUSES • father (“samy”, “ali”).

22. 1 Updating the facts section • To add a fact to the facts section use • asserta or assert to insert the new fact at the beginning of the fact section Will be added before the fact • Example: : father (“samy”, “ali”). – asserta( father(“ali”, ”ahmad”)). • assertz to add the fact at the end of its fact Will be added after the fact: section. father (“samy”, “ali”). – assertz( father(“ahmad”, ”khalil”)). If we execute the goal father ( X, Y). , The output will be as shown here: X=ali, Y=ahmad X=samy, Y=ali X=ahmad, Y=khalil

• There is no automatic check in VPROLOG if you insert a fact twice, to prevent this you can declare the following predicate which tests a fact before adding it as follows: Search for the fact • PREDICATES if found break Else assert it • uassert(up) • CLAUSES uassert (father(F, S)): - father(F, S), ! ; assert (father(F, S)).

22. 2 Saving and loading facts. • To save the facts in a file you can use the save predicate as follows: save (filename). Or Save (filename, factsectionname). • To load a fact database use consult as follows: consult (filename, factsectionname). DOMAINS person=string FACTS - up father (person, person) predicates uassert (up) addfathers repeat CLAUSES father ("samy", "ali"). uassert (father(F, S)): - father(F, S), ! ; assert (father(F, S)). repeat: - repeat. addfathers: - repeat, readln (F), readln (S), uassert(father(F, S)), F="", !, save("c: \facts", up). goal consult(“c: \facts”), addfathers, father(X, Y).

Removing facts • To remove a fact use the predicate retract as follows: retract(<the fact>[, factsectionname]). • Example to remove the fact father(“samy”, “ali”): retract(father(“samy”, ”ali”). • To remove all facts about “samy” as a father: retract (father(“samy”, _)). Note: the previous program adds a father whose name is null, to remove all facts that has a null string name modify the add father predicate as follows: addfathers: - repeat, readln (F), readln (S), uassert(father(F, S)), F="", !, retract(father(F, S)), save("c: \facts", up). To remove the last entered fact with null strings

f1f352f526145bb030fbb2302436a52c.ppt