d0618a81c93a630ba6847c857f64de93.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 81

2016 YEAR IN REVIEW CASES FROM THE SUPREME JUDICIAL COURT AND THE APPEALS COURT

2016 YEAR IN REVIEW CASES FROM THE SUPREME JUDICIAL COURT AND THE APPEALS COURT

Disclaimer: • This list is the product of four appellate attorneys reviewing all of the 2016 published opinions from the Appeals Court and Supreme Judicial Court • We hope it provides a decent review of the most important happenings in Massachusetts’s appellate courts • But reasonable minds can differ about what’s “important” and oversights happen. Please excuse any omissions.

Disclaimer: • This list is the product of four appellate attorneys reviewing all of the 2016 published opinions from the Appeals Court and Supreme Judicial Court • We hope it provides a decent review of the most important happenings in Massachusetts’s appellate courts • But reasonable minds can differ about what’s “important” and oversights happen. Please excuse any omissions.

What we’re not covering… • Dookhan cases and Bridgeman update • Padilla and immigration-related cases • Commonwealth v. Moore, 474 Mass. 541 (2016) (process for speaking to jurors post-trial). • Commonwealth v. Smith, 90 Mass. App. Ct. 261 (2016). These cases and topics will be covered by other presenters during this conference.

What we’re not covering… • Dookhan cases and Bridgeman update • Padilla and immigration-related cases • Commonwealth v. Moore, 474 Mass. 541 (2016) (process for speaking to jurors post-trial). • Commonwealth v. Smith, 90 Mass. App. Ct. 261 (2016). These cases and topics will be covered by other presenters during this conference.

MENS REA

MENS REA

Commonwealth v. Coggeshall, 473 Mass. 665 (2016). Statute requiring subjective intent • Reckless endangerment of child under G. L. c. 265, § 13 B requires proof of the defendant's subjective state of mind • Statute has an objective and subjective component • Defendant must actually know of risk - person “is aware of and consciously disregards” the risk • In contrast with common law objective standard for recklessness • Here: Probable cause existed where defendant was stumbling drunk on train tracks with 12 year-old son trying to hold him up. • He knew where he was, he was drunk, familiar with the railroad tracks, and had common knowledge that railroad tracks are dangerous places.

Commonwealth v. Coggeshall, 473 Mass. 665 (2016). Statute requiring subjective intent • Reckless endangerment of child under G. L. c. 265, § 13 B requires proof of the defendant's subjective state of mind • Statute has an objective and subjective component • Defendant must actually know of risk - person “is aware of and consciously disregards” the risk • In contrast with common law objective standard for recklessness • Here: Probable cause existed where defendant was stumbling drunk on train tracks with 12 year-old son trying to hold him up. • He knew where he was, he was drunk, familiar with the railroad tracks, and had common knowledge that railroad tracks are dangerous places.

Commonwealth v. Henderson, 89 Mass. App. Ct. 205 (2016). Subjective intent not required • G. L. c. 90 § 24(2)(a) – leaving the scene of an accident causing property damage. • Specific intent to leave the scene of an accident not an element of § 24(2)(a) • Enough that defendant knew about collision/injury and didn't stop. • Commonwealth v, Platt did not add a specific intent requirement • Older version of the statute had a specific intent requirement, but the amendment removing that language was purposeful. • Also: Proper unit of prosecution is the number of instances of leaving scene, not the number of victims (follows SJC in Constantino on similar question but different statute). • Near simultaneous collision with three cars, followed by flight from single scene, is single criminal design.

Commonwealth v. Henderson, 89 Mass. App. Ct. 205 (2016). Subjective intent not required • G. L. c. 90 § 24(2)(a) – leaving the scene of an accident causing property damage. • Specific intent to leave the scene of an accident not an element of § 24(2)(a) • Enough that defendant knew about collision/injury and didn't stop. • Commonwealth v, Platt did not add a specific intent requirement • Older version of the statute had a specific intent requirement, but the amendment removing that language was purposeful. • Also: Proper unit of prosecution is the number of instances of leaving scene, not the number of victims (follows SJC in Constantino on similar question but different statute). • Near simultaneous collision with three cars, followed by flight from single scene, is single criminal design.

Commonwealth v. Long, 90 Mass. App. Ct. 696 (2016). Non performance of a contract is NOT a crime Contractor did substandard, incomplete work for client, but evidence was insufficient to prove larceny by means of false pretenses • Larceny by false pretenses require “proof on an intention to deprive at the time of the representation” • No evidence that he never intended to finish job when he accepted money form the client. • Intending not to perform any work is different than intent to perform some or shoddy work.

Commonwealth v. Long, 90 Mass. App. Ct. 696 (2016). Non performance of a contract is NOT a crime Contractor did substandard, incomplete work for client, but evidence was insufficient to prove larceny by means of false pretenses • Larceny by false pretenses require “proof on an intention to deprive at the time of the representation” • No evidence that he never intended to finish job when he accepted money form the client. • Intending not to perform any work is different than intent to perform some or shoddy work.

INNOCENCE

INNOCENCE

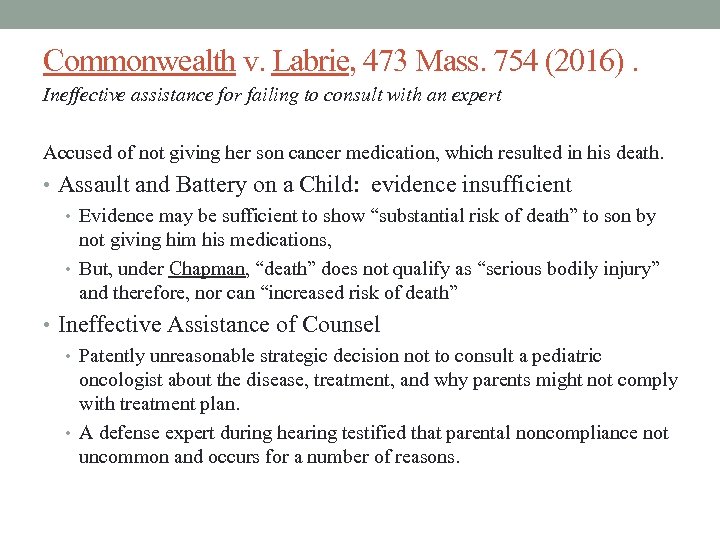

Commonwealth v. Labrie, 473 Mass. 754 (2016). Ineffective assistance for failing to consult with an expert Accused of not giving her son cancer medication, which resulted in his death. • Assault and Battery on a Child: evidence insufficient • Evidence may be sufficient to show “substantial risk of death” to son by not giving him his medications, • But, under Chapman, “death” does not qualify as “serious bodily injury” and therefore, nor can “increased risk of death” • Ineffective Assistance of Counsel • Patently unreasonable strategic decision not to consult a pediatric oncologist about the disease, treatment, and why parents might not comply with treatment plan. • A defense expert during hearing testified that parental noncompliance not uncommon and occurs for a number of reasons.

Commonwealth v. Labrie, 473 Mass. 754 (2016). Ineffective assistance for failing to consult with an expert Accused of not giving her son cancer medication, which resulted in his death. • Assault and Battery on a Child: evidence insufficient • Evidence may be sufficient to show “substantial risk of death” to son by not giving him his medications, • But, under Chapman, “death” does not qualify as “serious bodily injury” and therefore, nor can “increased risk of death” • Ineffective Assistance of Counsel • Patently unreasonable strategic decision not to consult a pediatric oncologist about the disease, treatment, and why parents might not comply with treatment plan. • A defense expert during hearing testified that parental noncompliance not uncommon and occurs for a number of reasons.

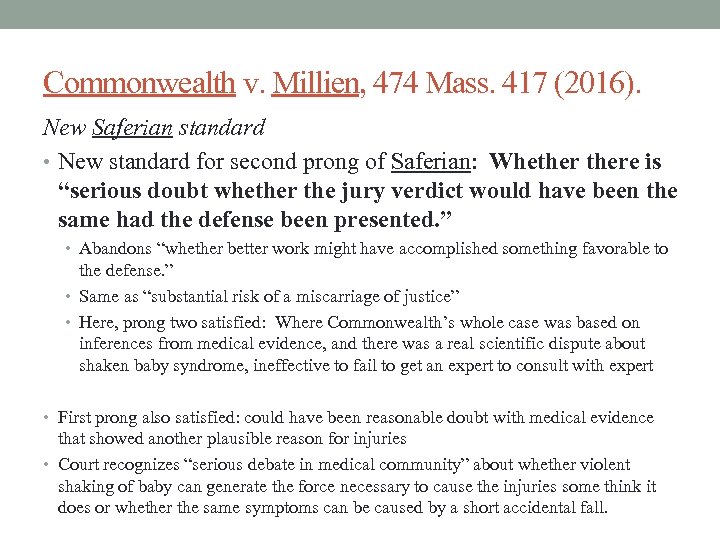

Commonwealth v. Millien, 474 Mass. 417 (2016). New Saferian standard • New standard for second prong of Saferian: Whethere is “serious doubt whether the jury verdict would have been the same had the defense been presented. ” • Abandons “whether better work might have accomplished something favorable to the defense. ” • Same as “substantial risk of a miscarriage of justice” • Here, prong two satisfied: Where Commonwealth’s whole case was based on inferences from medical evidence, and there was a real scientific dispute about shaken baby syndrome, ineffective to fail to get an expert to consult with expert • First prong also satisfied: could have been reasonable doubt with medical evidence that showed another plausible reason for injuries • Court recognizes “serious debate in medical community” about whether violent shaking of baby can generate the force necessary to cause the injuries some think it does or whether the same symptoms can be caused by a short accidental fall.

Commonwealth v. Millien, 474 Mass. 417 (2016). New Saferian standard • New standard for second prong of Saferian: Whethere is “serious doubt whether the jury verdict would have been the same had the defense been presented. ” • Abandons “whether better work might have accomplished something favorable to the defense. ” • Same as “substantial risk of a miscarriage of justice” • Here, prong two satisfied: Where Commonwealth’s whole case was based on inferences from medical evidence, and there was a real scientific dispute about shaken baby syndrome, ineffective to fail to get an expert to consult with expert • First prong also satisfied: could have been reasonable doubt with medical evidence that showed another plausible reason for injuries • Court recognizes “serious debate in medical community” about whether violent shaking of baby can generate the force necessary to cause the injuries some think it does or whether the same symptoms can be caused by a short accidental fall.

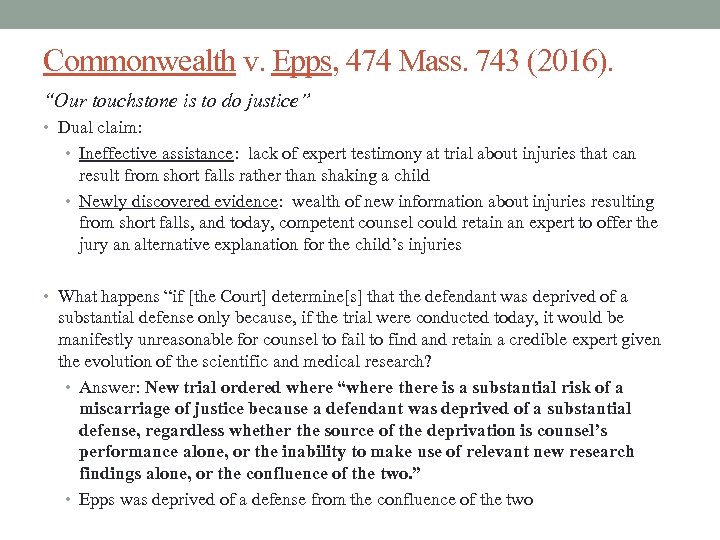

Commonwealth v. Epps, 474 Mass. 743 (2016). “Our touchstone is to do justice” • Dual claim: • Ineffective assistance: lack of expert testimony at trial about injuries that can result from short falls rather than shaking a child • Newly discovered evidence: wealth of new information about injuries resulting from short falls, and today, competent counsel could retain an expert to offer the jury an alternative explanation for the child’s injuries • What happens “if [the Court] determine[s] that the defendant was deprived of a substantial defense only because, if the trial were conducted today, it would be manifestly unreasonable for counsel to fail to find and retain a credible expert given the evolution of the scientific and medical research? • Answer: New trial ordered where “where there is a substantial risk of a miscarriage of justice because a defendant was deprived of a substantial defense, regardless whether the source of the deprivation is counsel’s performance alone, or the inability to make use of relevant new research findings alone, or the confluence of the two. ” • Epps was deprived of a defense from the confluence of the two

Commonwealth v. Epps, 474 Mass. 743 (2016). “Our touchstone is to do justice” • Dual claim: • Ineffective assistance: lack of expert testimony at trial about injuries that can result from short falls rather than shaking a child • Newly discovered evidence: wealth of new information about injuries resulting from short falls, and today, competent counsel could retain an expert to offer the jury an alternative explanation for the child’s injuries • What happens “if [the Court] determine[s] that the defendant was deprived of a substantial defense only because, if the trial were conducted today, it would be manifestly unreasonable for counsel to fail to find and retain a credible expert given the evolution of the scientific and medical research? • Answer: New trial ordered where “where there is a substantial risk of a miscarriage of justice because a defendant was deprived of a substantial defense, regardless whether the source of the deprivation is counsel’s performance alone, or the inability to make use of relevant new research findings alone, or the confluence of the two. ” • Epps was deprived of a defense from the confluence of the two

WITNESS INTIMIDATION

WITNESS INTIMIDATION

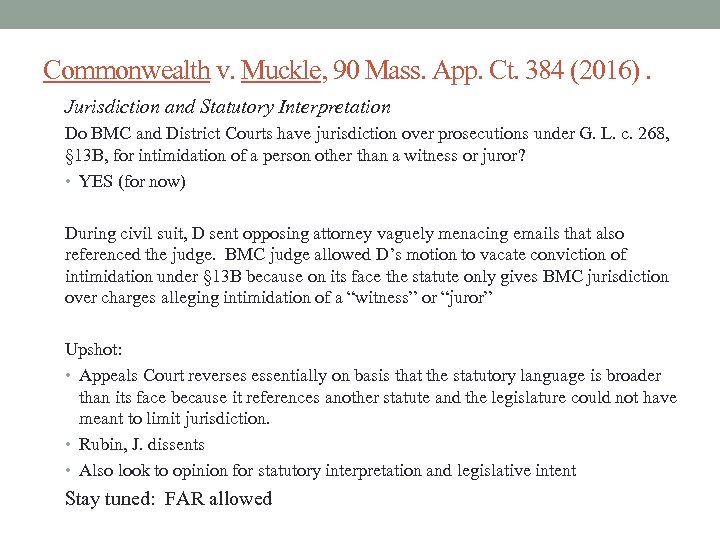

Commonwealth v. Muckle, 90 Mass. App. Ct. 384 (2016). Jurisdiction and Statutory Interpretation Do BMC and District Courts have jurisdiction over prosecutions under G. L. c. 268, § 13 B, for intimidation of a person other than a witness or juror? • YES (for now) During civil suit, D sent opposing attorney vaguely menacing emails that also referenced the judge. BMC judge allowed D’s motion to vacate conviction of intimidation under § 13 B because on its face the statute only gives BMC jurisdiction over charges alleging intimidation of a “witness” or “juror” Upshot: • Appeals Court reverses essentially on basis that the statutory language is broader than its face because it references another statute and the legislature could not have meant to limit jurisdiction. • Rubin, J. dissents • Also look to opinion for statutory interpretation and legislative intent Stay tuned: FAR allowed

Commonwealth v. Muckle, 90 Mass. App. Ct. 384 (2016). Jurisdiction and Statutory Interpretation Do BMC and District Courts have jurisdiction over prosecutions under G. L. c. 268, § 13 B, for intimidation of a person other than a witness or juror? • YES (for now) During civil suit, D sent opposing attorney vaguely menacing emails that also referenced the judge. BMC judge allowed D’s motion to vacate conviction of intimidation under § 13 B because on its face the statute only gives BMC jurisdiction over charges alleging intimidation of a “witness” or “juror” Upshot: • Appeals Court reverses essentially on basis that the statutory language is broader than its face because it references another statute and the legislature could not have meant to limit jurisdiction. • Rubin, J. dissents • Also look to opinion for statutory interpretation and legislative intent Stay tuned: FAR allowed

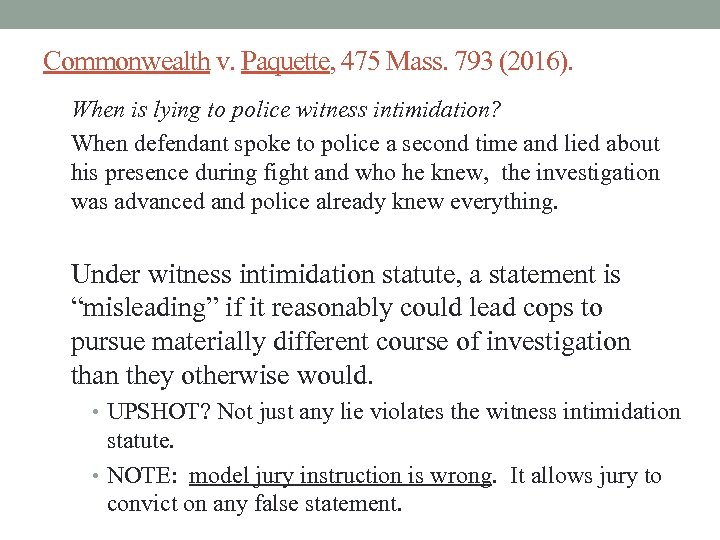

Commonwealth v. Paquette, 475 Mass. 793 (2016). When is lying to police witness intimidation? When defendant spoke to police a second time and lied about his presence during fight and who he knew, the investigation was advanced and police already knew everything. Under witness intimidation statute, a statement is “misleading” if it reasonably could lead cops to pursue materially different course of investigation than they otherwise would. • UPSHOT? Not just any lie violates the witness intimidation statute. • NOTE: model jury instruction is wrong. It allows jury to convict on any false statement.

Commonwealth v. Paquette, 475 Mass. 793 (2016). When is lying to police witness intimidation? When defendant spoke to police a second time and lied about his presence during fight and who he knew, the investigation was advanced and police already knew everything. Under witness intimidation statute, a statement is “misleading” if it reasonably could lead cops to pursue materially different course of investigation than they otherwise would. • UPSHOT? Not just any lie violates the witness intimidation statute. • NOTE: model jury instruction is wrong. It allows jury to convict on any false statement.

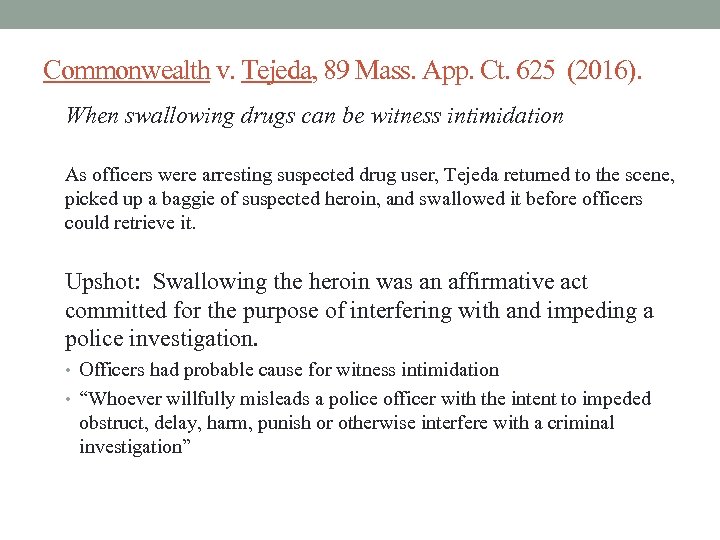

Commonwealth v. Tejeda, 89 Mass. App. Ct. 625 (2016). When swallowing drugs can be witness intimidation As officers were arresting suspected drug user, Tejeda returned to the scene, picked up a baggie of suspected heroin, and swallowed it before officers could retrieve it. Upshot: Swallowing the heroin was an affirmative act committed for the purpose of interfering with and impeding a police investigation. • Officers had probable cause for witness intimidation • “Whoever willfully misleads a police officer with the intent to impeded obstruct, delay, harm, punish or otherwise interfere with a criminal investigation”

Commonwealth v. Tejeda, 89 Mass. App. Ct. 625 (2016). When swallowing drugs can be witness intimidation As officers were arresting suspected drug user, Tejeda returned to the scene, picked up a baggie of suspected heroin, and swallowed it before officers could retrieve it. Upshot: Swallowing the heroin was an affirmative act committed for the purpose of interfering with and impeding a police investigation. • Officers had probable cause for witness intimidation • “Whoever willfully misleads a police officer with the intent to impeded obstruct, delay, harm, punish or otherwise interfere with a criminal investigation”

PROBATION

PROBATION

Commonwealth v. Moore, 473 Mass. 481 (2016). How much protection do parolees have? • Article 14 offers greater protection to parolees than the Fourth Amendment. But Article 14 offers less protection to parolees than it does to probationers. • Only “incrementally less” protection • “Individualized suspicion is still the appropriate standard” • Where parole officer has reasonable suspicion that there is evidence in parolee's home that he has violated, or is about to violate, a condition of his parole, a warrantless search of home is justified. • Evidence here: anonymous tip that parolee was dealing drugs. Officers looked at GPS records and got warrant for detainer. Made car stop and found nothing, then searched his house.

Commonwealth v. Moore, 473 Mass. 481 (2016). How much protection do parolees have? • Article 14 offers greater protection to parolees than the Fourth Amendment. But Article 14 offers less protection to parolees than it does to probationers. • Only “incrementally less” protection • “Individualized suspicion is still the appropriate standard” • Where parole officer has reasonable suspicion that there is evidence in parolee's home that he has violated, or is about to violate, a condition of his parole, a warrantless search of home is justified. • Evidence here: anonymous tip that parolee was dealing drugs. Officers looked at GPS records and got warrant for detainer. Made car stop and found nothing, then searched his house.

Commonwealth v. Waller, 90 Mass. App. Ct. 296 (2016). Can a probationer’s house just be open to searches? • Defendant convicted of animal cruelty where D’s dog starved to death. • Probation condition barring her from having pets was permissible • Probation condition that her home be “open for mandatory random inspections by the MSPCA and/or probation department” violates Article 14. • Reasonable suspicion required to search her home.

Commonwealth v. Waller, 90 Mass. App. Ct. 296 (2016). Can a probationer’s house just be open to searches? • Defendant convicted of animal cruelty where D’s dog starved to death. • Probation condition barring her from having pets was permissible • Probation condition that her home be “open for mandatory random inspections by the MSPCA and/or probation department” violates Article 14. • Reasonable suspicion required to search her home.

Commonwealth v. Obi, 475 Mass. 541 (2016). Defendant pushed Muslim tenant down stairs and said terrible things about Islam. • Probation condition requiring her to disclose her conviction to future tenants is enforceable. • Some limitation on probationer’s ability to make a profit is permissible where that limitation “substantially advances an enumerated probationary goal” • Here, it substantially advances the goal of public safety • Not so constitutionally burdensome to be invalid • Probation condition requiring her to take class on Islam was waived • But, “Conditions of probation touching on religion and risk incursion on constitutionally protected interests should be imposed only with great circumspection” • Probation condition of “respect” wasn’t actually a separate condition • The judge was just explaining his reasoning

Commonwealth v. Obi, 475 Mass. 541 (2016). Defendant pushed Muslim tenant down stairs and said terrible things about Islam. • Probation condition requiring her to disclose her conviction to future tenants is enforceable. • Some limitation on probationer’s ability to make a profit is permissible where that limitation “substantially advances an enumerated probationary goal” • Here, it substantially advances the goal of public safety • Not so constitutionally burdensome to be invalid • Probation condition requiring her to take class on Islam was waived • But, “Conditions of probation touching on religion and risk incursion on constitutionally protected interests should be imposed only with great circumspection” • Probation condition of “respect” wasn’t actually a separate condition • The judge was just explaining his reasoning

Commonwealth v. Grundman, 90 Mass. App. Ct. 403 (2016) When is a probation condition really a probation condition? Defendant pleaded guilty to rape of child, and was sentenced to prison time and probation. • Under G. L. c 265, § 47, GPS was mandatory, but it was not announced/discussed in court. • It was in probation contract, which the defendant signed. GPS is a condition of defendant's probation • Court distinguishes Selavka, which said that GPS under § 47 does not operate automatically even where it is mandatory. Defendant must have actual notice. • Defendant had actual notice here because sentence said probation was “subject to terms and conditions of probation department” and he signed conditions.

Commonwealth v. Grundman, 90 Mass. App. Ct. 403 (2016) When is a probation condition really a probation condition? Defendant pleaded guilty to rape of child, and was sentenced to prison time and probation. • Under G. L. c 265, § 47, GPS was mandatory, but it was not announced/discussed in court. • It was in probation contract, which the defendant signed. GPS is a condition of defendant's probation • Court distinguishes Selavka, which said that GPS under § 47 does not operate automatically even where it is mandatory. Defendant must have actual notice. • Defendant had actual notice here because sentence said probation was “subject to terms and conditions of probation department” and he signed conditions.

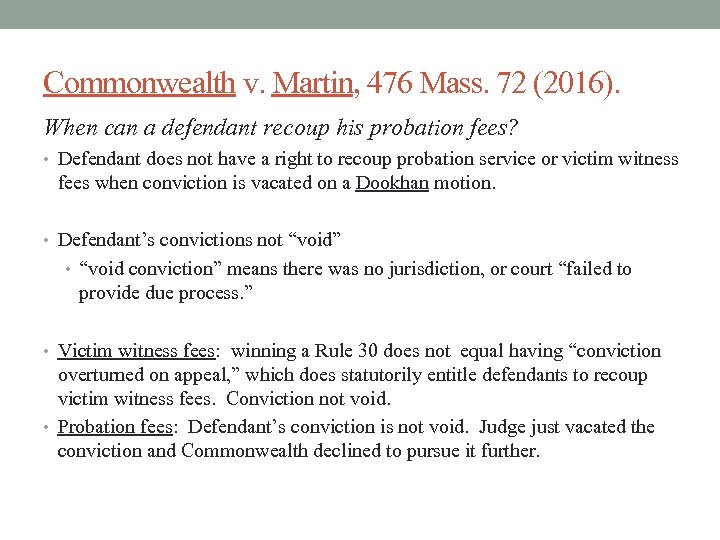

Commonwealth v. Martin, 476 Mass. 72 (2016). When can a defendant recoup his probation fees? • Defendant does not have a right to recoup probation service or victim witness fees when conviction is vacated on a Dookhan motion. • Defendant’s convictions not “void” • “void conviction” means there was no jurisdiction, or court “failed to provide due process. ” • Victim witness fees: winning a Rule 30 does not equal having “conviction overturned on appeal, ” which does statutorily entitle defendants to recoup victim witness fees. Conviction not void. • Probation fees: Defendant’s conviction is not void. Judge just vacated the conviction and Commonwealth declined to pursue it further.

Commonwealth v. Martin, 476 Mass. 72 (2016). When can a defendant recoup his probation fees? • Defendant does not have a right to recoup probation service or victim witness fees when conviction is vacated on a Dookhan motion. • Defendant’s convictions not “void” • “void conviction” means there was no jurisdiction, or court “failed to provide due process. ” • Victim witness fees: winning a Rule 30 does not equal having “conviction overturned on appeal, ” which does statutorily entitle defendants to recoup victim witness fees. Conviction not void. • Probation fees: Defendant’s conviction is not void. Judge just vacated the conviction and Commonwealth declined to pursue it further.

STRIP SEARCHES

STRIP SEARCHES

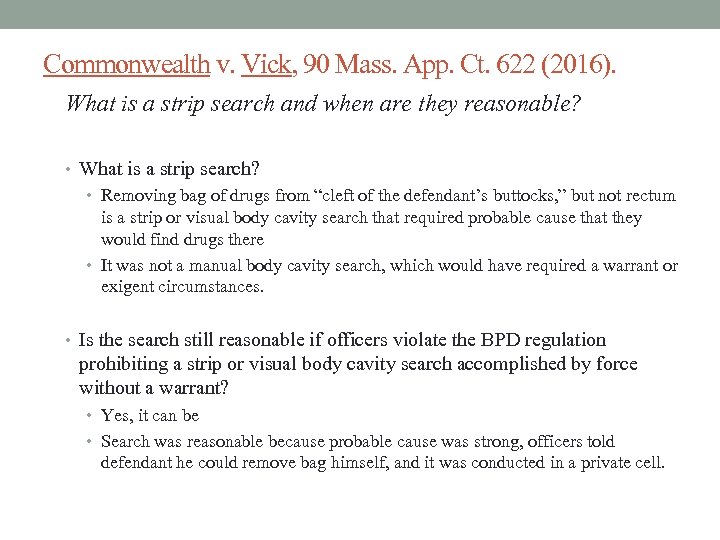

Commonwealth v. Vick, 90 Mass. App. Ct. 622 (2016). What is a strip search and when are they reasonable? • What is a strip search? • Removing bag of drugs from “cleft of the defendant’s buttocks, ” but not rectum is a strip or visual body cavity search that required probable cause that they would find drugs there • It was not a manual body cavity search, which would have required a warrant or exigent circumstances. • Is the search still reasonable if officers violate the BPD regulation prohibiting a strip or visual body cavity search accomplished by force without a warrant? • Yes, it can be • Search was reasonable because probable cause was strong, officers told defendant he could remove bag himself, and it was conducted in a private cell.

Commonwealth v. Vick, 90 Mass. App. Ct. 622 (2016). What is a strip search and when are they reasonable? • What is a strip search? • Removing bag of drugs from “cleft of the defendant’s buttocks, ” but not rectum is a strip or visual body cavity search that required probable cause that they would find drugs there • It was not a manual body cavity search, which would have required a warrant or exigent circumstances. • Is the search still reasonable if officers violate the BPD regulation prohibiting a strip or visual body cavity search accomplished by force without a warrant? • Yes, it can be • Search was reasonable because probable cause was strong, officers told defendant he could remove bag himself, and it was conducted in a private cell.

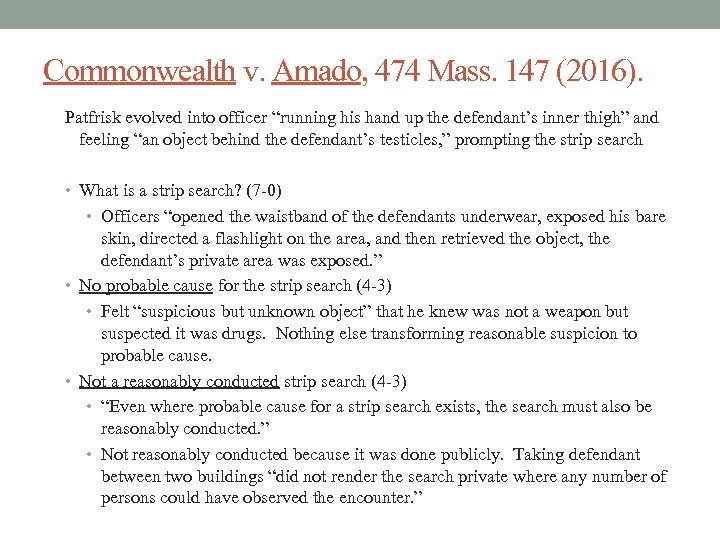

Commonwealth v. Amado, 474 Mass. 147 (2016). Patfrisk evolved into officer “running his hand up the defendant’s inner thigh” and feeling “an object behind the defendant’s testicles, ” prompting the strip search • What is a strip search? (7 -0) • Officers “opened the waistband of the defendants underwear, exposed his bare skin, directed a flashlight on the area, and then retrieved the object, the defendant’s private area was exposed. ” • No probable cause for the strip search (4 -3) • Felt “suspicious but unknown object” that he knew was not a weapon but suspected it was drugs. Nothing else transforming reasonable suspicion to probable cause. • Not a reasonably conducted strip search (4 -3) • “Even where probable cause for a strip search exists, the search must also be reasonably conducted. ” • Not reasonably conducted because it was done publicly. Taking defendant between two buildings “did not render the search private where any number of persons could have observed the encounter. ”

Commonwealth v. Amado, 474 Mass. 147 (2016). Patfrisk evolved into officer “running his hand up the defendant’s inner thigh” and feeling “an object behind the defendant’s testicles, ” prompting the strip search • What is a strip search? (7 -0) • Officers “opened the waistband of the defendants underwear, exposed his bare skin, directed a flashlight on the area, and then retrieved the object, the defendant’s private area was exposed. ” • No probable cause for the strip search (4 -3) • Felt “suspicious but unknown object” that he knew was not a weapon but suspected it was drugs. Nothing else transforming reasonable suspicion to probable cause. • Not a reasonably conducted strip search (4 -3) • “Even where probable cause for a strip search exists, the search must also be reasonably conducted. ” • Not reasonably conducted because it was done publicly. Taking defendant between two buildings “did not render the search private where any number of persons could have observed the encounter. ”

CELL PHONES

CELL PHONES

Commonwealth v. Dorelas, 473 Mass. 496 (2016). Standard to search a cell phone • Background: • Warrant affidavit: Defendant received threatening communication from people prior to shooting. • Search of phone: In “photos” file is photo of defendant in green jacket holding a gun (like shooter? ) • Defendant argued : warrant limited the search to call information and text files, not to all • Standard for searching a cell phone: • “a search must be done with special care and satisfy a more narrow and demanding standard” than the search of a closed container in the physical world. • Police must have information that “particularized evidence” related to the crime exists and probable cause only exists if the “particularized evidence” is likely to be found on the device. “Possibly found” is not enough. • Probable cause here. “Communications come in many forms, including photographic. So long as such evidence may reasonably be found in the photos file, that file may be searched. ”

Commonwealth v. Dorelas, 473 Mass. 496 (2016). Standard to search a cell phone • Background: • Warrant affidavit: Defendant received threatening communication from people prior to shooting. • Search of phone: In “photos” file is photo of defendant in green jacket holding a gun (like shooter? ) • Defendant argued : warrant limited the search to call information and text files, not to all • Standard for searching a cell phone: • “a search must be done with special care and satisfy a more narrow and demanding standard” than the search of a closed container in the physical world. • Police must have information that “particularized evidence” related to the crime exists and probable cause only exists if the “particularized evidence” is likely to be found on the device. “Possibly found” is not enough. • Probable cause here. “Communications come in many forms, including photographic. So long as such evidence may reasonably be found in the photos file, that file may be searched. ”

Continued… Commonwealth v. Dorelas • Dissent – Lenk, J. , joined by Duffly and Hines, JJ. • Not even “strong reason to suspect” that photos on phone were related to criminal activity being investigated, much less “substantial belief. ” Search should have been limited to texts and call data. • Allowing police to search broad variety of categories that were tangentially related to communications described in affidavit was an end-run around the particularity requirement. • Open question: how does plain view doctrine apply to cell phone searches?

Continued… Commonwealth v. Dorelas • Dissent – Lenk, J. , joined by Duffly and Hines, JJ. • Not even “strong reason to suspect” that photos on phone were related to criminal activity being investigated, much less “substantial belief. ” Search should have been limited to texts and call data. • Allowing police to search broad variety of categories that were tangentially related to communications described in affidavit was an end-run around the particularity requirement. • Open question: how does plain view doctrine apply to cell phone searches?

Commonwealth v. White, 475 Mass. 583 (2016). Is an officer’s belief enough for probable cause to search? • Background: Officers seize phone that was confiscated by defendant’s high school for unrelated reasons. Get warrant and search it 68 days later and find incriminating photo. • For cell phones or computer-like devices: no probable cause based just on officer’s belief that phone will have relevant evidence on it. • Belief does not furnish the nexus between the criminal activity and device searched. • Even where there is probable cause to suspect person, police may not seize or search his cell phone for evidence unless they have particularized evidence likely to be found there. • Court rejects notion of drawing automatic inference that if a person commits a crime, he must use his phone and, therefore, there’s evidence on the phone.

Commonwealth v. White, 475 Mass. 583 (2016). Is an officer’s belief enough for probable cause to search? • Background: Officers seize phone that was confiscated by defendant’s high school for unrelated reasons. Get warrant and search it 68 days later and find incriminating photo. • For cell phones or computer-like devices: no probable cause based just on officer’s belief that phone will have relevant evidence on it. • Belief does not furnish the nexus between the criminal activity and device searched. • Even where there is probable cause to suspect person, police may not seize or search his cell phone for evidence unless they have particularized evidence likely to be found there. • Court rejects notion of drawing automatic inference that if a person commits a crime, he must use his phone and, therefore, there’s evidence on the phone.

Quick Refresher • CSLI = Cellular site location information, a. k. a. information from cell towers that can track the location of a cell phone • Commonwealth v. Augustine – government compelled production of CSLI by a cell phone company is a search in the constitutional sense. The warrant requirement applies.

Quick Refresher • CSLI = Cellular site location information, a. k. a. information from cell towers that can track the location of a cell phone • Commonwealth v. Augustine – government compelled production of CSLI by a cell phone company is a search in the constitutional sense. The warrant requirement applies.

Commonwealth v. Broom, 474 Mass. 486 (2016). When does Augustine rule apply? CSLI Records • Defendant not entitled to benefit of Augustine I rule that warrant is needed for CSLI records • Case pending on appeal when case came out, but issue not raised below • Court says that if Augustine I applied, case would likely succeed • But… unobjected-to admission of CSLI evidence obtained without a warrant did not create substantial likelihood of miscarriage of justice? Cell Phone Search • Warrant for search of cell phone did not satisfy probable cause or particularity requirements • No “particularized evidence” suggesting contents of phone (contacts, voicemail, texts, e-mail, etc. ) were likely to contain information linking the defendant to the victim’s killing. • BUT. . Harmless. Nothing from phone introduced and content of only one text discussed at trial, and evidence overwhelming;

Commonwealth v. Broom, 474 Mass. 486 (2016). When does Augustine rule apply? CSLI Records • Defendant not entitled to benefit of Augustine I rule that warrant is needed for CSLI records • Case pending on appeal when case came out, but issue not raised below • Court says that if Augustine I applied, case would likely succeed • But… unobjected-to admission of CSLI evidence obtained without a warrant did not create substantial likelihood of miscarriage of justice? Cell Phone Search • Warrant for search of cell phone did not satisfy probable cause or particularity requirements • No “particularized evidence” suggesting contents of phone (contacts, voicemail, texts, e-mail, etc. ) were likely to contain information linking the defendant to the victim’s killing. • BUT. . Harmless. Nothing from phone introduced and content of only one text discussed at trial, and evidence overwhelming;

Commonwealth v. Balboni, 89 Mass. App. Ct. 651 (2016). When does Augustine rule apply? CSLI • Commonwealth sought CSLI records from Verizon pursuant to 18 U. S. C. § 2703(d) – before Augustine I announced warrant requirement • This case was pending on direct review when Augustine I issued • Warrant requirement from Augustine I applies here • BUT… Commonwealth met probable cause requirement based on affidavit originally submitted to support the s. 2703(d) order. Cell Phone Records • Commonwealth did not use proper procedure to summons cell phone records from Verizon. • No suppression because there is no prejudice. The defendant received the records in time to prepare a defense.

Commonwealth v. Balboni, 89 Mass. App. Ct. 651 (2016). When does Augustine rule apply? CSLI • Commonwealth sought CSLI records from Verizon pursuant to 18 U. S. C. § 2703(d) – before Augustine I announced warrant requirement • This case was pending on direct review when Augustine I issued • Warrant requirement from Augustine I applies here • BUT… Commonwealth met probable cause requirement based on affidavit originally submitted to support the s. 2703(d) order. Cell Phone Records • Commonwealth did not use proper procedure to summons cell phone records from Verizon. • No suppression because there is no prejudice. The defendant received the records in time to prepare a defense.

DECRIMINALIZATION OF POVERTY A glimmer of hope?

DECRIMINALIZATION OF POVERTY A glimmer of hope?

Commonwealth v. Magadini, 474 Mass. 593 (2016). “Our law does not permit punishment of the homeless simply for being homeless” • Necessity can be a defense to trespass • Homeless defendant charged with multiple counts of trespass, six of which for sleeping in building in Feb. and Mar. • “Clear and imminent danger” • For February and March offenses, but not June offense • “Availability of lawful alternatives: ” • Enough evidence to demonstrate a reasonable doubt that there were no effective legal alternatives available. Alternatives considered by a reasonable person in a similar situation • Does not require showing exhaustion of all conceivable alternatives or futile ones. • Application of Commonwealth v. Kendall, 451 Mass. 10 (2008), including dissent. .

Commonwealth v. Magadini, 474 Mass. 593 (2016). “Our law does not permit punishment of the homeless simply for being homeless” • Necessity can be a defense to trespass • Homeless defendant charged with multiple counts of trespass, six of which for sleeping in building in Feb. and Mar. • “Clear and imminent danger” • For February and March offenses, but not June offense • “Availability of lawful alternatives: ” • Enough evidence to demonstrate a reasonable doubt that there were no effective legal alternatives available. Alternatives considered by a reasonable person in a similar situation • Does not require showing exhaustion of all conceivable alternatives or futile ones. • Application of Commonwealth v. Kendall, 451 Mass. 10 (2008), including dissent. .

Commonwealth v. Henry, 475 Mass. 117 (2016). • In determining amount of restitution, a judge MUST consider a defendant’s ability to pay • Judge MAY NOT extend length of probation because of a defendant’s inability or limited ability to pay restitution • “extending the length of a probationary period because of a probationer’s inability to pay subjects the probationer to additional punishment solely because of his or her poverty” • Ability to pay determination made AFTER determining length of probation period. • Decided under superintendence power

Commonwealth v. Henry, 475 Mass. 117 (2016). • In determining amount of restitution, a judge MUST consider a defendant’s ability to pay • Judge MAY NOT extend length of probation because of a defendant’s inability or limited ability to pay restitution • “extending the length of a probationary period because of a probationer’s inability to pay subjects the probationer to additional punishment solely because of his or her poverty” • Ability to pay determination made AFTER determining length of probation period. • Decided under superintendence power

Continued… Commonwealth v. Henry, 475 Mass. 117 (2016) • How much should a defendant pay? • Legal standard for ability to pay: income, net assets, and financial obligations such as food, shelter, and clothes for defendant and dependents. “Should not cause a defendant substantial financial hardship” • Where a defendant is indigent, “judge should consider carefully whether restitution can be ordered without causing substantial financial hardship • In retain theft cases, amount of economic loss for restitution purposes is the replacement value of the goods • Unless Commonwealth proves by preponderance that good would have otherwise sold, in which case retail value may be used

Continued… Commonwealth v. Henry, 475 Mass. 117 (2016) • How much should a defendant pay? • Legal standard for ability to pay: income, net assets, and financial obligations such as food, shelter, and clothes for defendant and dependents. “Should not cause a defendant substantial financial hardship” • Where a defendant is indigent, “judge should consider carefully whether restitution can be ordered without causing substantial financial hardship • In retain theft cases, amount of economic loss for restitution purposes is the replacement value of the goods • Unless Commonwealth proves by preponderance that good would have otherwise sold, in which case retail value may be used

ATTEMPT

ATTEMPT

Commonwealth v. Robert Mc. Williams, 473 Mass. 606 (Feb. 12, 2016) (Spina, J. ) • When have you not gone far enough to be guilty of attempt? • When does preparation for a crime = attempt to commit crime? • There are two types of attempt: final act completed & preparation. • Factors: Degree of proximity to consummation, gravity of crime, uncertainty of result, seriousness of harm. • Sufficient Evidence of Attempt: Defendant sits outside of the bank he’d robbed 3 weeks earlier, wearing a wig and carrying a bag with a fake beard and a pellet gun. • Court: He was sitting close to the bank; he had then-present ability to walk in and rob it; same clothes; disguise; holding “similar bag” as last time. • “Reasonable jury could conclude that it was virtually certain that he would have robbed the bank a second time” if he hadn’t been stopped. • ALSO: Court closes door left open in CW v. Fortunato, 466 Mass. 500 (2013). Holds that “volunteered, unsolicited statements” made more than six hours after arrest do not require suppression.

Commonwealth v. Robert Mc. Williams, 473 Mass. 606 (Feb. 12, 2016) (Spina, J. ) • When have you not gone far enough to be guilty of attempt? • When does preparation for a crime = attempt to commit crime? • There are two types of attempt: final act completed & preparation. • Factors: Degree of proximity to consummation, gravity of crime, uncertainty of result, seriousness of harm. • Sufficient Evidence of Attempt: Defendant sits outside of the bank he’d robbed 3 weeks earlier, wearing a wig and carrying a bag with a fake beard and a pellet gun. • Court: He was sitting close to the bank; he had then-present ability to walk in and rob it; same clothes; disguise; holding “similar bag” as last time. • “Reasonable jury could conclude that it was virtually certain that he would have robbed the bank a second time” if he hadn’t been stopped. • ALSO: Court closes door left open in CW v. Fortunato, 466 Mass. 500 (2013). Holds that “volunteered, unsolicited statements” made more than six hours after arrest do not require suppression.

Commonwealth v. Kenneth Dykens, 473 Mass. 635 (Feb. 17, 2016) (Cordy, J. ) • WORLD’S WORST BURGLAR! • 4 -3 opinion (Duffly, J. , dissenting, with Lenk and Hines JJ. ) • Majority: Rejects argument that all overt acts directed toward committing a single crime constitute a single attempt. • Each act undertaken = sufficient “overt act” to be punished as attempt. • Defendant “had the opportunity to abandon his endeavors” each time he failed. • Court distinguishes b/t continuous actions (e. g. , “repeatedly battering a single door” = one attempt) and the discrete acts undertaken here (3 acts at 3 separate access points). • Duffly Dissent: Does NOT disagree with the key holding. Instead, says that tearing a screen off a window and leaning a ladder are insufficient overt acts to constitute “attempts. ” • ALSO: A rock is not a burglar’s tool. Tool = man-made item.

Commonwealth v. Kenneth Dykens, 473 Mass. 635 (Feb. 17, 2016) (Cordy, J. ) • WORLD’S WORST BURGLAR! • 4 -3 opinion (Duffly, J. , dissenting, with Lenk and Hines JJ. ) • Majority: Rejects argument that all overt acts directed toward committing a single crime constitute a single attempt. • Each act undertaken = sufficient “overt act” to be punished as attempt. • Defendant “had the opportunity to abandon his endeavors” each time he failed. • Court distinguishes b/t continuous actions (e. g. , “repeatedly battering a single door” = one attempt) and the discrete acts undertaken here (3 acts at 3 separate access points). • Duffly Dissent: Does NOT disagree with the key holding. Instead, says that tearing a screen off a window and leaning a ladder are insufficient overt acts to constitute “attempts. ” • ALSO: A rock is not a burglar’s tool. Tool = man-made item.

Commonwealth v. Kristen La. Brie, 473 Mass. 754 (March 9, 2016) (Botsford, J. ) • When have you gone too far to be guilty of attempt? • WORTH A READ. • Facts: Mother convicted of attempted murder for withholding cancer medication from her son. With treatment, long-term survival rate ~ 85 -90%. Son died. • HELD: “Nonachievement” is NOT an element of attempted murder, though it is “clearly relevant. ” • “[W]hether a particular act qualifies as an overt act that … constitutes a criminal attempt does not depend on whether the substantive crime has or has not been accomplished. ” • ATTEMPT = Specific intent to commit substantive crime + overt act toward its completion. • Court vacated the attempted murder and A&B convictions on other grounds, affirmed reckless endangerment conviction. • ALSO: • Counsel ineffective for failure to consult with independent oncologist. Patently unreasonable strategic decision given oncologist’s testimony during MNT hearing that parents don’t adhere to treatment plans for a number of reasons. Conviction vacated! • FN 31: This was trial counsel’s first criminal case in the Superior Court.

Commonwealth v. Kristen La. Brie, 473 Mass. 754 (March 9, 2016) (Botsford, J. ) • When have you gone too far to be guilty of attempt? • WORTH A READ. • Facts: Mother convicted of attempted murder for withholding cancer medication from her son. With treatment, long-term survival rate ~ 85 -90%. Son died. • HELD: “Nonachievement” is NOT an element of attempted murder, though it is “clearly relevant. ” • “[W]hether a particular act qualifies as an overt act that … constitutes a criminal attempt does not depend on whether the substantive crime has or has not been accomplished. ” • ATTEMPT = Specific intent to commit substantive crime + overt act toward its completion. • Court vacated the attempted murder and A&B convictions on other grounds, affirmed reckless endangerment conviction. • ALSO: • Counsel ineffective for failure to consult with independent oncologist. Patently unreasonable strategic decision given oncologist’s testimony during MNT hearing that parents don’t adhere to treatment plans for a number of reasons. Conviction vacated! • FN 31: This was trial counsel’s first criminal case in the Superior Court.

Commonwealth v. David Coutu, 90 Mass. App. Ct. 227 (Sept. 15, 2016) (Meade, J. ) • First time case was in AC: • Coutu I, 88 Mass. App. Ct. 686 (2015) – Court reversed D’s conviction for attempted arson based on insufficient evidence. FAR was granted and remanded in light of La. Brie. • Appeals Court happy to reinstate conviction. • In broad strokes, the issue was whether evidence support attempt conviction even though jury could have concluded that D achieved the substantive crime of arson. “The box was actually ablaze before the victim extinguished it. ” • HOLDING: The rule of La. Brie applies to the attempted arson statute (MGL c. 255 s. 5 A), even though the statute is different than the general attempt statute.

Commonwealth v. David Coutu, 90 Mass. App. Ct. 227 (Sept. 15, 2016) (Meade, J. ) • First time case was in AC: • Coutu I, 88 Mass. App. Ct. 686 (2015) – Court reversed D’s conviction for attempted arson based on insufficient evidence. FAR was granted and remanded in light of La. Brie. • Appeals Court happy to reinstate conviction. • In broad strokes, the issue was whether evidence support attempt conviction even though jury could have concluded that D achieved the substantive crime of arson. “The box was actually ablaze before the victim extinguished it. ” • HOLDING: The rule of La. Brie applies to the attempted arson statute (MGL c. 255 s. 5 A), even though the statute is different than the general attempt statute.

EYEWITNESS IDENTIFICATION

EYEWITNESS IDENTIFICATION

Commonwealth v. Kyle Johnson, 473 Mass. 594 (Feb. 12, 2016) (Gants, C. J. ) • THIRD PARTY ID PROCEDURE: Where out of court ID is not conducted by police, “common law principles of fairness” require suppression if the ID is unreliable due to highlysuggestive procedure. • Principle is basically exercise of 403 – out-of-court is rendered more prejudicial than probative. • Motions to suppress are procedurally similar in both police & third-party contexts – • must be timely filed by D + D bears burden of proof by preponderance. • Rules are substantively different: • Article XII is a per se rule of exclusion; common law principle is based upon weighing of probative value and prejudice. • Appellate review is different. Article XII review is clearly erroneous for facts but de novo on the law. Common law review is for abuse of discretion. • ALSO: Independent source doctrine does not apply. In-court ID cannot be admitted when out-of -court ID is found unreliable. • See CW v. Dasheem Dew (SJC-12225) (April argument).

Commonwealth v. Kyle Johnson, 473 Mass. 594 (Feb. 12, 2016) (Gants, C. J. ) • THIRD PARTY ID PROCEDURE: Where out of court ID is not conducted by police, “common law principles of fairness” require suppression if the ID is unreliable due to highlysuggestive procedure. • Principle is basically exercise of 403 – out-of-court is rendered more prejudicial than probative. • Motions to suppress are procedurally similar in both police & third-party contexts – • must be timely filed by D + D bears burden of proof by preponderance. • Rules are substantively different: • Article XII is a per se rule of exclusion; common law principle is based upon weighing of probative value and prejudice. • Appellate review is different. Article XII review is clearly erroneous for facts but de novo on the law. Common law review is for abuse of discretion. • ALSO: Independent source doctrine does not apply. In-court ID cannot be admitted when out-of -court ID is found unreliable. • See CW v. Dasheem Dew (SJC-12225) (April argument).

Commonwealth v. Santiago Navarro, 474 Mass. 247 (May 5, 2016) (Hines, J. ) • Armed robbery of high-stakes poker game. Co-D testified against D at trial. Only 2 of 6 victims picked D out of photo array. • HOLDING: Defendant is not entitled to a sua sponte Rodriguez instruction. BUT it was ineffective for counsel not to request it. BUT there was insufficient prejudice because of the strength of the evidence. • Rodriguez, 378 Mass. 296 (1979): Outlines model instruction on the risk of misidentification and the factors jury should consider in assessing ID accuracy. • Model Instruction, 473 Mass. 1051 (Nov. 16, 2015), available on SJC website.

Commonwealth v. Santiago Navarro, 474 Mass. 247 (May 5, 2016) (Hines, J. ) • Armed robbery of high-stakes poker game. Co-D testified against D at trial. Only 2 of 6 victims picked D out of photo array. • HOLDING: Defendant is not entitled to a sua sponte Rodriguez instruction. BUT it was ineffective for counsel not to request it. BUT there was insufficient prejudice because of the strength of the evidence. • Rodriguez, 378 Mass. 296 (1979): Outlines model instruction on the risk of misidentification and the factors jury should consider in assessing ID accuracy. • Model Instruction, 473 Mass. 1051 (Nov. 16, 2015), available on SJC website.

Commonwealth v. Frankie Herndon, 475 Mass. 324 (Aug. 26, 2016) (Botsford, J. ) • Court affirms 1 st degree murder conviction. • HELD: No error in refusing to provide better instructions on eyewitness ID when defendant was tried before release of new model instructions. Gomes was prospective only. • The defendant requested an instruction that included principles subsequently added to the model instruction, but it didn’t matter. • HELD: “[A]s a matter of criminal procedure, the Commonwealth shall be required to question a putative identification witness concerning an alleged prior identification before it seeks to introduce substantive evidence of that identification through a third party. ” • Not a constitutionally-required rule. • Court doubles down on Cong Duc Le, 444 Mass. 431 (2005): ID statements are admissible substantively so long as the declarant is subject to cross-examination (regardless of whether he admits, denies, or does not remember statement). This does not violate confrontation right. • Here, CW introduced witness’s pretrial ID of defendant through police officers when witness stated he did not recall conversation. But that error did not require reversal.

Commonwealth v. Frankie Herndon, 475 Mass. 324 (Aug. 26, 2016) (Botsford, J. ) • Court affirms 1 st degree murder conviction. • HELD: No error in refusing to provide better instructions on eyewitness ID when defendant was tried before release of new model instructions. Gomes was prospective only. • The defendant requested an instruction that included principles subsequently added to the model instruction, but it didn’t matter. • HELD: “[A]s a matter of criminal procedure, the Commonwealth shall be required to question a putative identification witness concerning an alleged prior identification before it seeks to introduce substantive evidence of that identification through a third party. ” • Not a constitutionally-required rule. • Court doubles down on Cong Duc Le, 444 Mass. 431 (2005): ID statements are admissible substantively so long as the declarant is subject to cross-examination (regardless of whether he admits, denies, or does not remember statement). This does not violate confrontation right. • Here, CW introduced witness’s pretrial ID of defendant through police officers when witness stated he did not recall conversation. But that error did not require reversal.

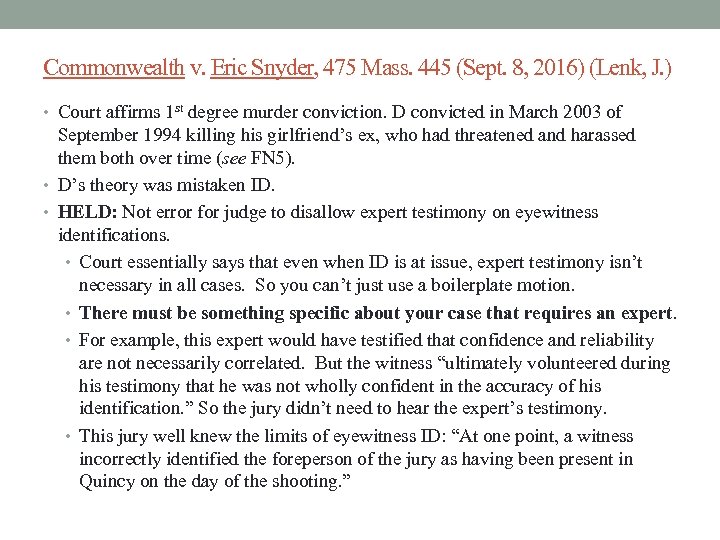

Commonwealth v. Eric Snyder, 475 Mass. 445 (Sept. 8, 2016) (Lenk, J. ) • Court affirms 1 st degree murder conviction. D convicted in March 2003 of September 1994 killing his girlfriend’s ex, who had threatened and harassed them both over time (see FN 5). • D’s theory was mistaken ID. • HELD: Not error for judge to disallow expert testimony on eyewitness identifications. • Court essentially says that even when ID is at issue, expert testimony isn’t necessary in all cases. So you can’t just use a boilerplate motion. • There must be something specific about your case that requires an expert. • For example, this expert would have testified that confidence and reliability are not necessarily correlated. But the witness “ultimately volunteered during his testimony that he was not wholly confident in the accuracy of his identification. ” So the jury didn’t need to hear the expert’s testimony. • This jury well knew the limits of eyewitness ID: “At one point, a witness incorrectly identified the foreperson of the jury as having been present in Quincy on the day of the shooting. ”

Commonwealth v. Eric Snyder, 475 Mass. 445 (Sept. 8, 2016) (Lenk, J. ) • Court affirms 1 st degree murder conviction. D convicted in March 2003 of September 1994 killing his girlfriend’s ex, who had threatened and harassed them both over time (see FN 5). • D’s theory was mistaken ID. • HELD: Not error for judge to disallow expert testimony on eyewitness identifications. • Court essentially says that even when ID is at issue, expert testimony isn’t necessary in all cases. So you can’t just use a boilerplate motion. • There must be something specific about your case that requires an expert. • For example, this expert would have testified that confidence and reliability are not necessarily correlated. But the witness “ultimately volunteered during his testimony that he was not wholly confident in the accuracy of his identification. ” So the jury didn’t need to hear the expert’s testimony. • This jury well knew the limits of eyewitness ID: “At one point, a witness incorrectly identified the foreperson of the jury as having been present in Quincy on the day of the shooting. ”

ARMED CAREER CRIMINAL ACT

ARMED CAREER CRIMINAL ACT

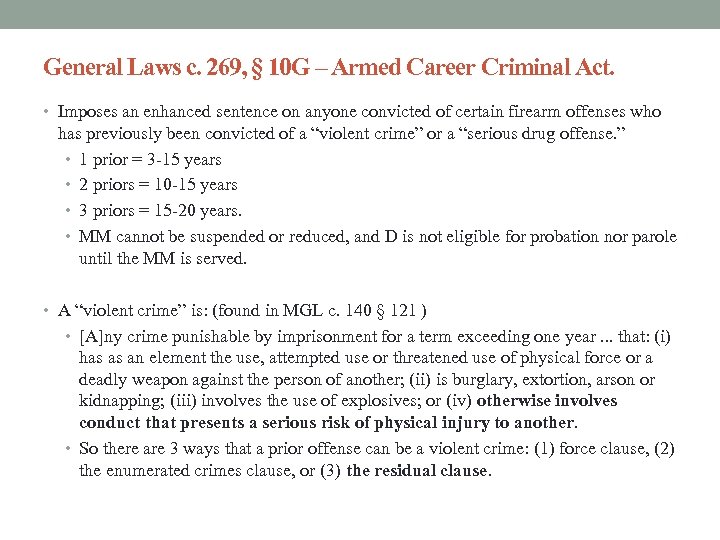

General Laws c. 269, § 10 G – Armed Career Criminal Act. • Imposes an enhanced sentence on anyone convicted of certain firearm offenses who has previously been convicted of a “violent crime” or a “serious drug offense. ” • 1 prior = 3 -15 years • 2 priors = 10 -15 years • 3 priors = 15 -20 years. • MM cannot be suspended or reduced, and D is not eligible for probation nor parole until the MM is served. • A “violent crime” is: (found in MGL c. 140 § 121 ) • [A]ny crime punishable by imprisonment for a term exceeding one year. . . that: (i) has as an element the use, attempted use or threatened use of physical force or a deadly weapon against the person of another; (ii) is burglary, extortion, arson or kidnapping; (iii) involves the use of explosives; or (iv) otherwise involves conduct that presents a serious risk of physical injury to another. • So there are 3 ways that a prior offense can be a violent crime: (1) force clause, (2) the enumerated crimes clause, or (3) the residual clause.

General Laws c. 269, § 10 G – Armed Career Criminal Act. • Imposes an enhanced sentence on anyone convicted of certain firearm offenses who has previously been convicted of a “violent crime” or a “serious drug offense. ” • 1 prior = 3 -15 years • 2 priors = 10 -15 years • 3 priors = 15 -20 years. • MM cannot be suspended or reduced, and D is not eligible for probation nor parole until the MM is served. • A “violent crime” is: (found in MGL c. 140 § 121 ) • [A]ny crime punishable by imprisonment for a term exceeding one year. . . that: (i) has as an element the use, attempted use or threatened use of physical force or a deadly weapon against the person of another; (ii) is burglary, extortion, arson or kidnapping; (iii) involves the use of explosives; or (iv) otherwise involves conduct that presents a serious risk of physical injury to another. • So there are 3 ways that a prior offense can be a violent crime: (1) force clause, (2) the enumerated crimes clause, or (3) the residual clause.

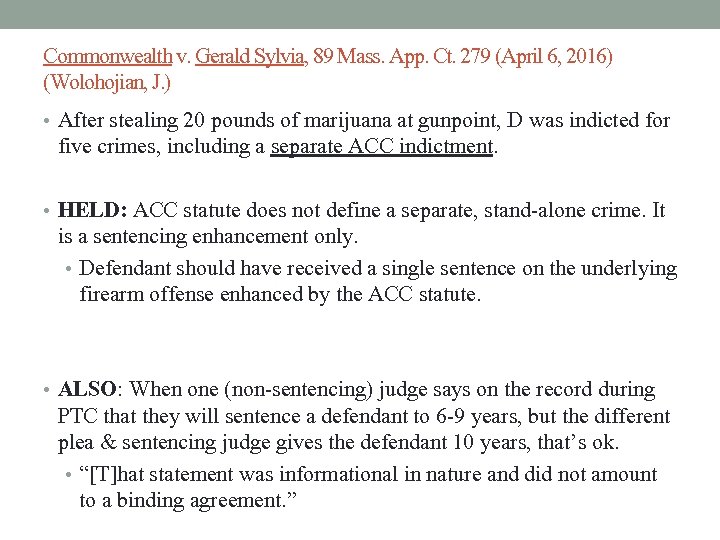

Commonwealth v. Gerald Sylvia, 89 Mass. App. Ct. 279 (April 6, 2016) (Wolohojian, J. ) • After stealing 20 pounds of marijuana at gunpoint, D was indicted for five crimes, including a separate ACC indictment. • HELD: ACC statute does not define a separate, stand-alone crime. It is a sentencing enhancement only. • Defendant should have received a single sentence on the underlying firearm offense enhanced by the ACC statute. • ALSO: When one (non-sentencing) judge says on the record during PTC that they will sentence a defendant to 6 -9 years, but the different plea & sentencing judge gives the defendant 10 years, that’s ok. • “[T]hat statement was informational in nature and did not amount to a binding agreement. ”

Commonwealth v. Gerald Sylvia, 89 Mass. App. Ct. 279 (April 6, 2016) (Wolohojian, J. ) • After stealing 20 pounds of marijuana at gunpoint, D was indicted for five crimes, including a separate ACC indictment. • HELD: ACC statute does not define a separate, stand-alone crime. It is a sentencing enhancement only. • Defendant should have received a single sentence on the underlying firearm offense enhanced by the ACC statute. • ALSO: When one (non-sentencing) judge says on the record during PTC that they will sentence a defendant to 6 -9 years, but the different plea & sentencing judge gives the defendant 10 years, that’s ok. • “[T]hat statement was informational in nature and did not amount to a binding agreement. ”

Commonwealth v. Daunte Beal, 474 Mass. 341 (May 24, 2016) (Duffly, J. ) • Defendant convicted of various crimes arising out of a shooting in Dorchester, and the firearm offense included an ACC enhancement. • HELD: Residual clause’s definition of a “violent crime” is unconstitutionally vague. • Adheres to SCOTUS holding in Johnson v. United States, 135 S. Ct. 2551 (2015) (Scalia, J. ) – categorical approach/ordinary case analysis leads to too much uncertainty and vagueness. CW agreed. • Definition of violent crime is in MGL c. 140 s. 121 Any time you see this definition incorporated into anything (ACCA or not) you should be making this argument. • Same definition is in MGL c. 127 s. 133 E Also ripe for challenge. • D’s predicates here – A&B and A&B on a public employee – did not satisfy the force clause of the ACCA, so it could not be a basis for enhancement. A&B is not categorically a crime of violence under the ACCA. • NOTE: In April 2016, SCOTUS held that Johnson is retroactive to final sentences of federal prisoners. See Welch v. United States, 136 S. Ct. 1257 (2016). • So we should be making the same argument about Beal.

Commonwealth v. Daunte Beal, 474 Mass. 341 (May 24, 2016) (Duffly, J. ) • Defendant convicted of various crimes arising out of a shooting in Dorchester, and the firearm offense included an ACC enhancement. • HELD: Residual clause’s definition of a “violent crime” is unconstitutionally vague. • Adheres to SCOTUS holding in Johnson v. United States, 135 S. Ct. 2551 (2015) (Scalia, J. ) – categorical approach/ordinary case analysis leads to too much uncertainty and vagueness. CW agreed. • Definition of violent crime is in MGL c. 140 s. 121 Any time you see this definition incorporated into anything (ACCA or not) you should be making this argument. • Same definition is in MGL c. 127 s. 133 E Also ripe for challenge. • D’s predicates here – A&B and A&B on a public employee – did not satisfy the force clause of the ACCA, so it could not be a basis for enhancement. A&B is not categorically a crime of violence under the ACCA. • NOTE: In April 2016, SCOTUS held that Johnson is retroactive to final sentences of federal prisoners. See Welch v. United States, 136 S. Ct. 1257 (2016). • So we should be making the same argument about Beal.

Commonwealth v. Admilson Resende, 474 Mass. 455 (June 9, 2016) (Botsford, J. ) • HELD: Previous convictions for predicate offenses should be treated as a single predicate conviction when they were all charged as part of a single prosecution. • D had five priors for distribution, but all the counts were included in a single set of charges. Court held that those five priors would count only as one ACC predicate. • The point of the ACCA is to increase punishment when people persevere with criminality “despite theoretically beneficial effects of penal discipline. ” So you punish more severely as the defendant has more opportunities for reform, but fails. • So could this rule be extended to context in which crimes are charged separately, but there’s no intervening discipline? YES! (see Cordy, J. , below) • This matters because the enhancement is so draconian. Defendant now subject to 3 year MM rather than 15 year MM. On resentencing, the defendant got five to five and a day, and was home a month after the rescript from the SJC. • Cordy J. , joined by Spina, J. , Dissent: State ACCA unambiguously means separate criminal incidents. • Cordy does a parade of horribles about the majority’s logic, and you want to use those horribles to help you to try to extend Resende.

Commonwealth v. Admilson Resende, 474 Mass. 455 (June 9, 2016) (Botsford, J. ) • HELD: Previous convictions for predicate offenses should be treated as a single predicate conviction when they were all charged as part of a single prosecution. • D had five priors for distribution, but all the counts were included in a single set of charges. Court held that those five priors would count only as one ACC predicate. • The point of the ACCA is to increase punishment when people persevere with criminality “despite theoretically beneficial effects of penal discipline. ” So you punish more severely as the defendant has more opportunities for reform, but fails. • So could this rule be extended to context in which crimes are charged separately, but there’s no intervening discipline? YES! (see Cordy, J. , below) • This matters because the enhancement is so draconian. Defendant now subject to 3 year MM rather than 15 year MM. On resentencing, the defendant got five to five and a day, and was home a month after the rescript from the SJC. • Cordy J. , joined by Spina, J. , Dissent: State ACCA unambiguously means separate criminal incidents. • Cordy does a parade of horribles about the majority’s logic, and you want to use those horribles to help you to try to extend Resende.

PORNOGRAPHY

PORNOGRAPHY

Commonwealth v. Glenn Christie, 89 Mass. App. Ct. 665 (July 5, 2016) (Rubin, J. ) • Vacates conviction for statutory rape and indecent A&B because the trial court (Lowy, J. ) admitted testimony concerning same-sex pornography in D’s possession to demonstrate D’s sexual interest in the alleged victim (a 12 year-old boy). • Judge Lowy recognized the prejudice, because he didn’t allow the pornography to be played for the jury. He instead let an officer describe what was on the tapes. • Judge gave a limiting instruction: Testimony was only admitted to show D’s sexual interest and state of mind as it relates to the victim and the manner and means by which D accomplished the alleged sexual assault. • HELD: Homosexuality is irrelevant to whether D has sexual interest in children (“ingrained stereotypes and mistaken views”). Adult pornography probative only of same-sex interest is thus inadmissible to show sexual interest in children. • Pornography is only admissible where it is “specifically probative of that interest” in children.

Commonwealth v. Glenn Christie, 89 Mass. App. Ct. 665 (July 5, 2016) (Rubin, J. ) • Vacates conviction for statutory rape and indecent A&B because the trial court (Lowy, J. ) admitted testimony concerning same-sex pornography in D’s possession to demonstrate D’s sexual interest in the alleged victim (a 12 year-old boy). • Judge Lowy recognized the prejudice, because he didn’t allow the pornography to be played for the jury. He instead let an officer describe what was on the tapes. • Judge gave a limiting instruction: Testimony was only admitted to show D’s sexual interest and state of mind as it relates to the victim and the manner and means by which D accomplished the alleged sexual assault. • HELD: Homosexuality is irrelevant to whether D has sexual interest in children (“ingrained stereotypes and mistaken views”). Adult pornography probative only of same-sex interest is thus inadmissible to show sexual interest in children. • Pornography is only admissible where it is “specifically probative of that interest” in children.

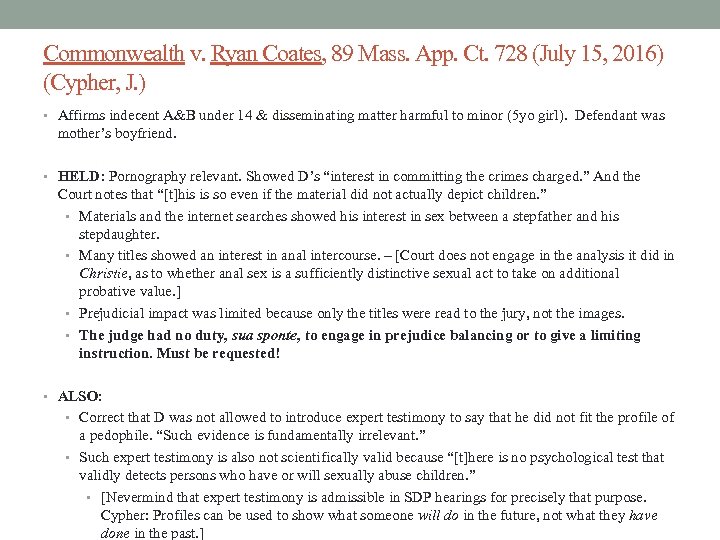

Commonwealth v. Ryan Coates, 89 Mass. App. Ct. 728 (July 15, 2016) (Cypher, J. ) • Affirms indecent A&B under 14 & disseminating matter harmful to minor (5 yo girl). Defendant was mother’s boyfriend. • HELD: Pornography relevant. Showed D’s “interest in committing the crimes charged. ” And the Court notes that “[t]his is so even if the material did not actually depict children. ” • Materials and the internet searches showed his interest in sex between a stepfather and his stepdaughter. • Many titles showed an interest in anal intercourse. – [Court does not engage in the analysis it did in Christie, as to whether anal sex is a sufficiently distinctive sexual act to take on additional probative value. ] • Prejudicial impact was limited because only the titles were read to the jury, not the images. • The judge had no duty, sua sponte, to engage in prejudice balancing or to give a limiting instruction. Must be requested! • ALSO: • Correct that D was not allowed to introduce expert testimony to say that he did not fit the profile of a pedophile. “Such evidence is fundamentally irrelevant. ” • Such expert testimony is also not scientifically valid because “[t]here is no psychological test that validly detects persons who have or will sexually abuse children. ” • [Nevermind that expert testimony is admissible in SDP hearings for precisely that purpose. Cypher: Profiles can be used to show what someone will do in the future, not what they have done in the past. ]

Commonwealth v. Ryan Coates, 89 Mass. App. Ct. 728 (July 15, 2016) (Cypher, J. ) • Affirms indecent A&B under 14 & disseminating matter harmful to minor (5 yo girl). Defendant was mother’s boyfriend. • HELD: Pornography relevant. Showed D’s “interest in committing the crimes charged. ” And the Court notes that “[t]his is so even if the material did not actually depict children. ” • Materials and the internet searches showed his interest in sex between a stepfather and his stepdaughter. • Many titles showed an interest in anal intercourse. – [Court does not engage in the analysis it did in Christie, as to whether anal sex is a sufficiently distinctive sexual act to take on additional probative value. ] • Prejudicial impact was limited because only the titles were read to the jury, not the images. • The judge had no duty, sua sponte, to engage in prejudice balancing or to give a limiting instruction. Must be requested! • ALSO: • Correct that D was not allowed to introduce expert testimony to say that he did not fit the profile of a pedophile. “Such evidence is fundamentally irrelevant. ” • Such expert testimony is also not scientifically valid because “[t]here is no psychological test that validly detects persons who have or will sexually abuse children. ” • [Nevermind that expert testimony is admissible in SDP hearings for precisely that purpose. Cypher: Profiles can be used to show what someone will do in the future, not what they have done in the past. ]

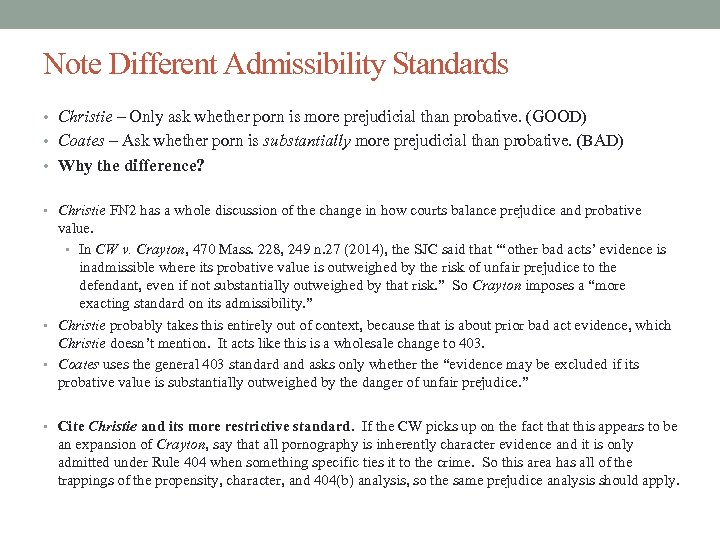

Note Different Admissibility Standards • Christie – Only ask whether porn is more prejudicial than probative. (GOOD) • Coates – Ask whether porn is substantially more prejudicial than probative. (BAD) • Why the difference? • Christie FN 2 has a whole discussion of the change in how courts balance prejudice and probative value. • In CW v. Crayton, 470 Mass. 228, 249 n. 27 (2014), the SJC said that “‘other bad acts’ evidence is inadmissible where its probative value is outweighed by the risk of unfair prejudice to the defendant, even if not substantially outweighed by that risk. ” So Crayton imposes a “more exacting standard on its admissibility. ” • Christie probably takes this entirely out of context, because that is about prior bad act evidence, which Christie doesn’t mention. It acts like this is a wholesale change to 403. • Coates uses the general 403 standard and asks only whether the “evidence may be excluded if its probative value is substantially outweighed by the danger of unfair prejudice. ” • Cite Christie and its more restrictive standard. If the CW picks up on the fact that this appears to be an expansion of Crayton, say that all pornography is inherently character evidence and it is only admitted under Rule 404 when something specific ties it to the crime. So this area has all of the trappings of the propensity, character, and 404(b) analysis, so the same prejudice analysis should apply.

Note Different Admissibility Standards • Christie – Only ask whether porn is more prejudicial than probative. (GOOD) • Coates – Ask whether porn is substantially more prejudicial than probative. (BAD) • Why the difference? • Christie FN 2 has a whole discussion of the change in how courts balance prejudice and probative value. • In CW v. Crayton, 470 Mass. 228, 249 n. 27 (2014), the SJC said that “‘other bad acts’ evidence is inadmissible where its probative value is outweighed by the risk of unfair prejudice to the defendant, even if not substantially outweighed by that risk. ” So Crayton imposes a “more exacting standard on its admissibility. ” • Christie probably takes this entirely out of context, because that is about prior bad act evidence, which Christie doesn’t mention. It acts like this is a wholesale change to 403. • Coates uses the general 403 standard and asks only whether the “evidence may be excluded if its probative value is substantially outweighed by the danger of unfair prejudice. ” • Cite Christie and its more restrictive standard. If the CW picks up on the fact that this appears to be an expansion of Crayton, say that all pornography is inherently character evidence and it is only admitted under Rule 404 when something specific ties it to the crime. So this area has all of the trappings of the propensity, character, and 404(b) analysis, so the same prejudice analysis should apply.

RANDOM SUPPRESSION CASES

RANDOM SUPPRESSION CASES

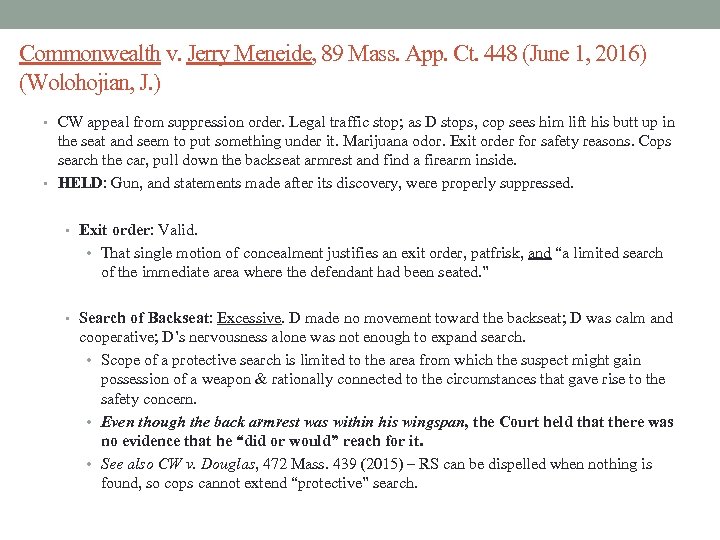

Commonwealth v. Jerry Meneide, 89 Mass. App. Ct. 448 (June 1, 2016) (Wolohojian, J. ) • CW appeal from suppression order. Legal traffic stop; as D stops, cop sees him lift his butt up in the seat and seem to put something under it. Marijuana odor. Exit order for safety reasons. Cops search the car, pull down the backseat armrest and find a firearm inside. • HELD: Gun, and statements made after its discovery, were properly suppressed. • Exit order: Valid. • That single motion of concealment justifies an exit order, patfrisk, and “a limited search of the immediate area where the defendant had been seated. ” • Search of Backseat: Excessive. D made no movement toward the backseat; D was calm and cooperative; D’s nervousness alone was not enough to expand search. • Scope of a protective search is limited to the area from which the suspect might gain possession of a weapon & rationally connected to the circumstances that gave rise to the safety concern. • Even though the back armrest was within his wingspan, the Court held that there was no evidence that he “did or would” reach for it. • See also CW v. Douglas, 472 Mass. 439 (2015) – RS can be dispelled when nothing is found, so cops cannot extend “protective” search.

Commonwealth v. Jerry Meneide, 89 Mass. App. Ct. 448 (June 1, 2016) (Wolohojian, J. ) • CW appeal from suppression order. Legal traffic stop; as D stops, cop sees him lift his butt up in the seat and seem to put something under it. Marijuana odor. Exit order for safety reasons. Cops search the car, pull down the backseat armrest and find a firearm inside. • HELD: Gun, and statements made after its discovery, were properly suppressed. • Exit order: Valid. • That single motion of concealment justifies an exit order, patfrisk, and “a limited search of the immediate area where the defendant had been seated. ” • Search of Backseat: Excessive. D made no movement toward the backseat; D was calm and cooperative; D’s nervousness alone was not enough to expand search. • Scope of a protective search is limited to the area from which the suspect might gain possession of a weapon & rationally connected to the circumstances that gave rise to the safety concern. • Even though the back armrest was within his wingspan, the Court held that there was no evidence that he “did or would” reach for it. • See also CW v. Douglas, 472 Mass. 439 (2015) – RS can be dispelled when nothing is found, so cops cannot extend “protective” search.

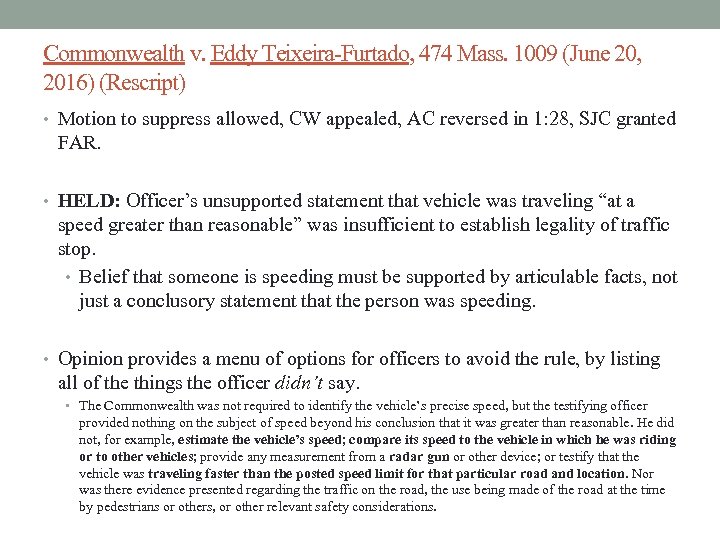

Commonwealth v. Eddy Teixeira-Furtado, 474 Mass. 1009 (June 20, 2016) (Rescript) • Motion to suppress allowed, CW appealed, AC reversed in 1: 28, SJC granted FAR. • HELD: Officer’s unsupported statement that vehicle was traveling “at a speed greater than reasonable” was insufficient to establish legality of traffic stop. • Belief that someone is speeding must be supported by articulable facts, not just a conclusory statement that the person was speeding. • Opinion provides a menu of options for officers to avoid the rule, by listing all of the things the officer didn’t say. • The Commonwealth was not required to identify the vehicle’s precise speed, but the testifying officer provided nothing on the subject of speed beyond his conclusion that it was greater than reasonable. He did not, for example, estimate the vehicle’s speed; compare its speed to the vehicle in which he was riding or to other vehicles; provide any measurement from a radar gun or other device; or testify that the vehicle was traveling faster than the posted speed limit for that particular road and location. Nor was there evidence presented regarding the traffic on the road, the use being made of the road at the time by pedestrians or others, or other relevant safety considerations.

Commonwealth v. Eddy Teixeira-Furtado, 474 Mass. 1009 (June 20, 2016) (Rescript) • Motion to suppress allowed, CW appealed, AC reversed in 1: 28, SJC granted FAR. • HELD: Officer’s unsupported statement that vehicle was traveling “at a speed greater than reasonable” was insufficient to establish legality of traffic stop. • Belief that someone is speeding must be supported by articulable facts, not just a conclusory statement that the person was speeding. • Opinion provides a menu of options for officers to avoid the rule, by listing all of the things the officer didn’t say. • The Commonwealth was not required to identify the vehicle’s precise speed, but the testifying officer provided nothing on the subject of speed beyond his conclusion that it was greater than reasonable. He did not, for example, estimate the vehicle’s speed; compare its speed to the vehicle in which he was riding or to other vehicles; provide any measurement from a radar gun or other device; or testify that the vehicle was traveling faster than the posted speed limit for that particular road and location. Nor was there evidence presented regarding the traffic on the road, the use being made of the road at the time by pedestrians or others, or other relevant safety considerations.

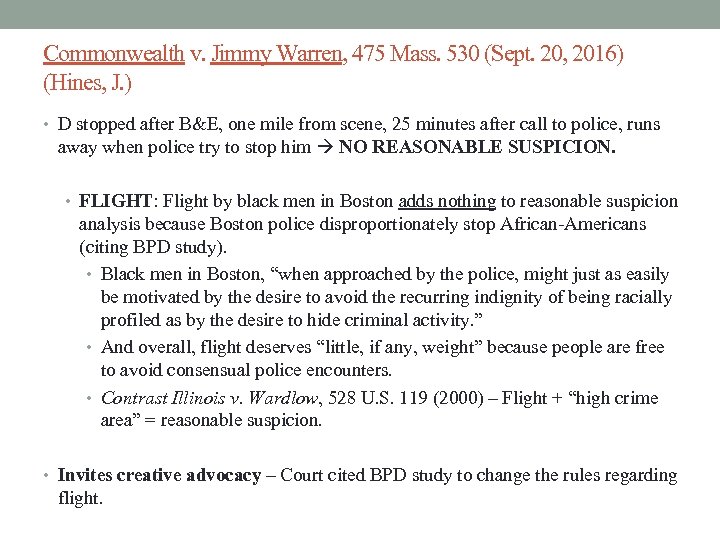

Commonwealth v. Jimmy Warren, 475 Mass. 530 (Sept. 20, 2016) (Hines, J. ) • D stopped after B&E, one mile from scene, 25 minutes after call to police, runs away when police try to stop him NO REASONABLE SUSPICION. • FLIGHT: Flight by black men in Boston adds nothing to reasonable suspicion analysis because Boston police disproportionately stop African-Americans (citing BPD study). • Black men in Boston, “when approached by the police, might just as easily be motivated by the desire to avoid the recurring indignity of being racially profiled as by the desire to hide criminal activity. ” • And overall, flight deserves “little, if any, weight” because people are free to avoid consensual police encounters. • Contrast Illinois v. Wardlow, 528 U. S. 119 (2000) – Flight + “high crime area” = reasonable suspicion. • Invites creative advocacy – Court cited BPD study to change the rules regarding flight.

Commonwealth v. Jimmy Warren, 475 Mass. 530 (Sept. 20, 2016) (Hines, J. ) • D stopped after B&E, one mile from scene, 25 minutes after call to police, runs away when police try to stop him NO REASONABLE SUSPICION. • FLIGHT: Flight by black men in Boston adds nothing to reasonable suspicion analysis because Boston police disproportionately stop African-Americans (citing BPD study). • Black men in Boston, “when approached by the police, might just as easily be motivated by the desire to avoid the recurring indignity of being racially profiled as by the desire to hide criminal activity. ” • And overall, flight deserves “little, if any, weight” because people are free to avoid consensual police encounters. • Contrast Illinois v. Wardlow, 528 U. S. 119 (2000) – Flight + “high crime area” = reasonable suspicion. • Invites creative advocacy – Court cited BPD study to change the rules regarding flight.

IMPOUNDMENT & INVENTORY SEARCHES

IMPOUNDMENT & INVENTORY SEARCHES

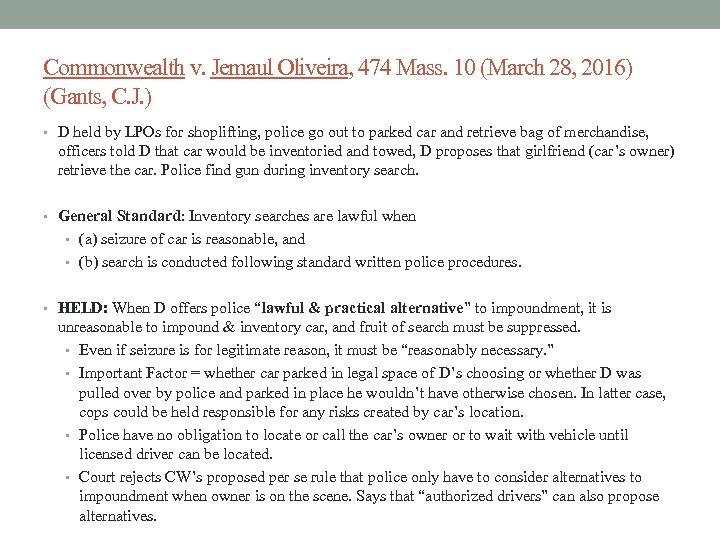

Commonwealth v. Jemaul Oliveira, 474 Mass. 10 (March 28, 2016) (Gants, C. J. ) • D held by LPOs for shoplifting, police go out to parked car and retrieve bag of merchandise, officers told D that car would be inventoried and towed, D proposes that girlfriend (car’s owner) retrieve the car. Police find gun during inventory search. • General Standard: Inventory searches are lawful when • (a) seizure of car is reasonable, and • (b) search is conducted following standard written police procedures. • HELD: When D offers police “lawful & practical alternative” to impoundment, it is unreasonable to impound & inventory car, and fruit of search must be suppressed. • Even if seizure is for legitimate reason, it must be “reasonably necessary. ” • Important Factor = whether car parked in legal space of D’s choosing or whether D was pulled over by police and parked in place he wouldn’t have otherwise chosen. In latter case, cops could be held responsible for any risks created by car’s location. • Police have no obligation to locate or call the car’s owner or to wait with vehicle until licensed driver can be located. • Court rejects CW’s proposed per se rule that police only have to consider alternatives to impoundment when owner is on the scene. Says that “authorized drivers” can also propose alternatives.