58f1f38cb602566ea31ae8b9fae1d8a3.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 28

2014 NOPT National Conference Thursday 16 th October Luther King House Manchester M 14 5 JP Relationships Matter The importance of the concept ‘use of self’ and its importance in relationship-based practice Dr Pamela Trevithick Visiting Professor in Social Work, Buckinghamshire New University/ GAPS Project Manager

The importance of relationshipbased practice

Trevithick, P. (2003) ‘Effective relationship-based practice: a theoretical exploration’, Journal of Social Work Practice, 173 -186 17(2):

A definition of relationship-based practice Relationship-based practice supports the view that the relationships we create are fundamental to understanding and action, and it is this understanding and the meaning given to experience - that shapes the way we work with people. The aware and unaware emotions and feelings that all parties bring to an encounter – and the impact of wider social factors constitute a central element of the understanding that is achieved and the actions based on that understanding

The importance of relationships: the contribution of neuroscience ‘Relationship experiences have a dominant influence on t brain. . . Interpersonal experience thus plays a special organising role in determining the development of brain structure early in life and the ongoing emergence of brain function throughout the lifespan’ 33) (Siegal 2012: ‘The very nature of humanity arises from relationships. . essentially everythingsthat ’ important about life as a human being you learn in context of relationships ’ (Perry 2003)

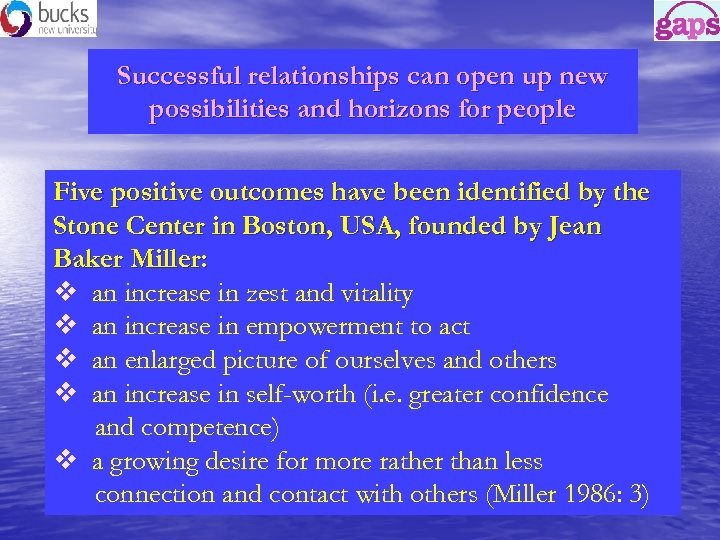

Successful relationships can open up new possibilities and horizons for people Five positive outcomes have been identified by the Stone Center in Boston, USA, founded by Jean Baker Miller: v an increase in zest and vitality v an increase in empowerment to act v an enlarged picture of ourselves and others v an increase in self-worth (i. e. greater confidence and competence) v a growing desire for more rather than less connection and contact with others (Miller 1986: 3)

The ‘professional use of self’

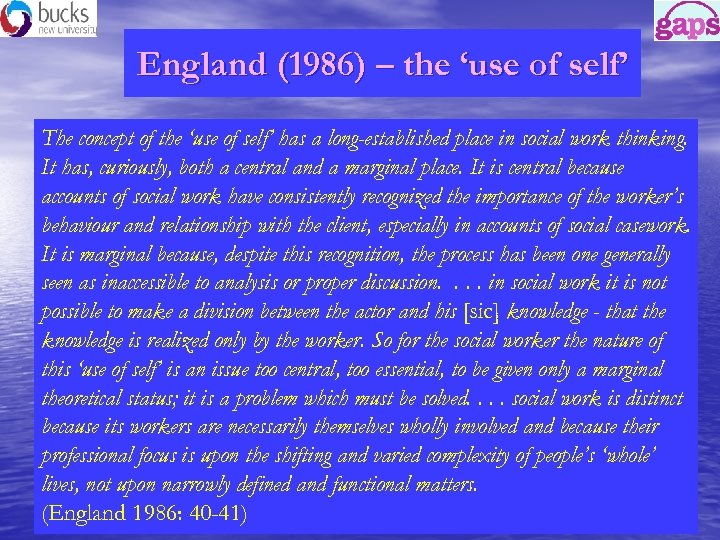

England (1986) – the ‘use of self’ The concept of the ‘use of self’ has a long-established place in social work thinking. It has, curiously, both a central and a marginal place. It is central because accounts of social work have consistently recognized the importance of the worker’s behaviour and relationship with the client, especially in accounts of social casework. It is marginal because, despite this recognition, the process has been one generally seen as inaccessible to analysis or proper discussion. . in social work it is not possible to make a division between the actor and his [sic] knowledge - that the knowledge is realized only by the worker. So for the social worker the nature of this ‘use of self’ is an issue too central, too essential, to be given only a marginal theoretical status; it is a problem which must be solved. . social work is distinct because its workers are necessarily themselves wholly involved and because their professional focus is upon the shifting and varied complexity of people’s ‘whole’ lives, not upon narrowly defined and functional matters. (England 1986: 40 -41)

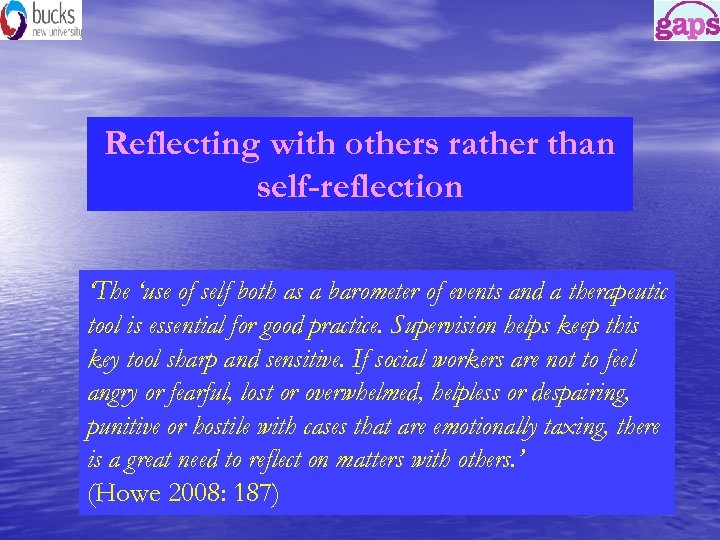

Reflecting with others rather than self-reflection ‘The ‘use of self both as a barometer of events and a therapeutic tool is essential for good practice. Supervision helps keep this key tool sharp and sensitive. If social workers are not to feel angry or fearful, lost or overwhelmed, helpless or despairing, punitive or hostile with cases that are emotionally taxing, there is a great need to reflect on matters with others. ’ (Howe 2008: 187)

The importance of self knowledge It can: 1. enhance our capacity to understand others: The capacity to be in touch with the service user’s feelings is related to the worker’s ability to acknowledge his or her own. Before a worker can understand the power of emotions in the life of the client, it is necessary to discover its importance in the worker’s own experience. (Schulman 1999: 156) 2. enhance our capacity to understand ourselves and how we come across 3. help us to understand how service users ‘use themselves’ and the extent to which they can use their self-knowledge to understand others

A conundrum: our explicit self-aware self and our implicit self ‘Things that we are conscious about make up the explicit aspects of the self. These are what we refer to by the term selfaware and constitute what we call our self-concepts. . The implicit aspects of the self, by contrast, are all other aspects of who we are that are not immediately available to consciousness, either because they are by their nature inaccessible, or because they are accessible but not being accessed at the moment. ’ (Le. Doux 2002: 27 -28)

Non-verbal cues The nature of the emotional states among human beings can be hidden so considerable emphasis needs to be placed on the emotional message that is conveyed in non-verbal cues , particularly in people’s facial expression – as Seigal notes: The study of emotion suggests that nonverbal behaviour is a primary mode in which emotion is communicated. Facial expression, eye gaze, tone of voice, bodily motion, and the timing and intensity of response are all fundamental to emotional messages. (Seigal 2012: 146) Seigal goes further to state: ‘we are hard-wired to have meaning and emotion shaped by the perception of eye contact and facial expression. We are also hard-wired to express emotion through the face. ’ (Siegal 2012: 176).

We need to use all our senses to aid understanding and to gather evidence It is essential to look for evidence that confirms your hypothesis – but also evidence that refutes what you think to be happening. In every encounter we need to use all the five senses: v v v sight hearing touch e. g. offering a handshake as a form of communications/comforting others through touch v smell v taste The importance of: giving words to feeling felt but not named

Positive relationships are conveyed in the ‘professional use of self’ a) facial expression b) tone of voice/intensity/rhythm/speed and quality of speech c) choice of words/vocabulary/articulation d) other gestures we adopt e) mode of dress f) actions/behaviour – as evident in our reliability, consistency and punctuality The ‘use of self’ calls for practitioners to be aware of ‘how we come across’ - and how to adapt our approach to take account of non-verbal forms of communication – in ourselves and in others in way that aid communication and engagement

a. default facial expression Le. Doux: ‘the expression of emotion on a human face is a potent poten emotional stimulus’. Le. Doux cites a research study which indicated: ‘that exposure of human subjects to fearful or angry faces poten activates the amygdala’ (Le. Doux 2002: 220) That is, expressions that are interpreted as hostile (although perhaps not purposely intended) can trigger a person’s fight, flight or freeze reaction – which from that moment will change the nature of the communication unless addressed

a. default facial expression A great deal is communicated through our facial expression, particularly eye contact. Some examples of our default facial expression include: A warm and inviting face A calm and comforting face A face that’s had to read A face that conveys disinterest A sad face A worried face (e. g. such as a frown) etc.

b. default vocal expression Examples of differences in tone of voice, mode of speech, the speed that we use to communicate: v speaking with a hurried tone v speaking with a dreary, boring, monosyllabic, noncommittal or disinterested tone v speaking with a warm, caring, inviting, inclusive tone v speaking with an excited, interested, animated tone v speaking with changes in tone in order to emphasise certain points

c. default choice of words/vocabulary Importance of cultural sensitivity. . . v our choice of words can have a profound impact v people’s class, race, gender, age and other identities tend to shape communication among different groups. It is essential not to work from a stereotypical view of people v failure to understand cultural differences – and differences in power and status - can lead to misunderstandings/ communication breakdown

d. default gestures we adopt There are gestures or repetitive mannerisms we adopt of which we are unaware. The most obvious examples include: v v fidgeting/tapping clicking pens looking away failing to keep eye contact when needed the overuse certain words or phrases, such as: ‘right ’ ‘ok’ ‘you know what I mean ’ The most effective way to identify these gestures is through the use of a video recording - or by asking a colleague for honest but caring and sensitive feedback

e. default mode of dress A fifth area where the professional use of self is important relates to how we dress and communicated through our appearance – that is, what we intend or may be interpreted in how we dress. For example, how much skin we reveal can interfere with the communication. Thoughtfulness and sensitivity is needed in this area e. g. power dressing. ‘The way we dress communicates symbolically something of ourselves, and will have symbolic meaning for clients (and colleagues) depending on age, culture, class and context’ (Lishman 2009: 29)

f. Reliability, consistency and punctuality A sixth area: Being reliable and consistent can lead to a lowering of defences because it can mean that the emotional energy taken up through feeling worried or apprehensive about our arrival and how we might respond can be freed up and used instead to address concerns Punctuality often conveys to others their importance and the commitment given to the encounter or the work at hand

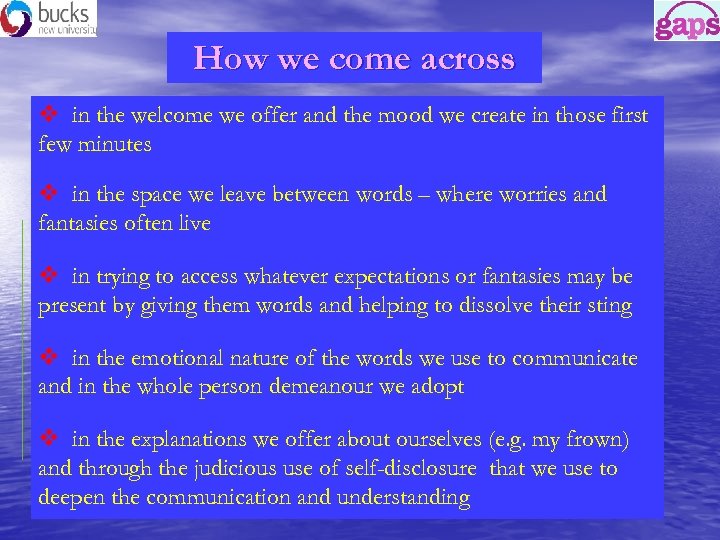

How we come across v in the welcome we offer and the mood we create in those first few minutes v in the space we leave between words – where worries and fantasies often live v in trying to access whatever expectations or fantasies may be present by giving them words and helping to dissolve their sting v in the emotional nature of the words we use to communicate and in the whole person demeanour we adopt v in the explanations we offer about ourselves (e. g. my frown) and through the judicious use of self-disclosure that we use to deepen the communication and understanding

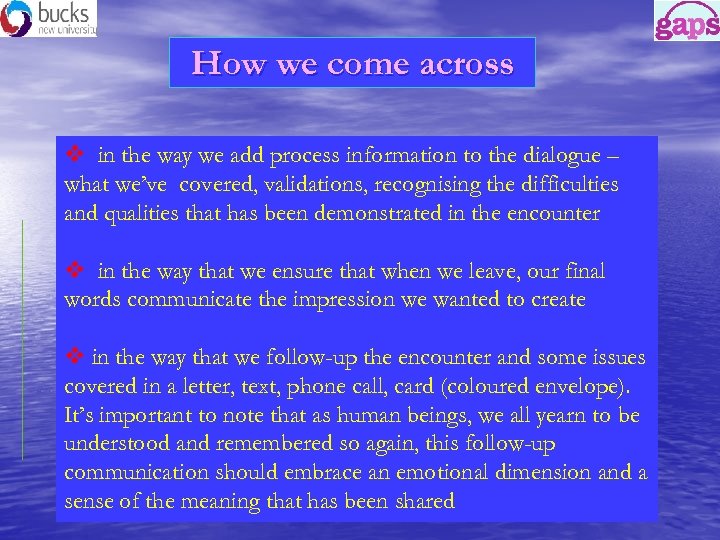

How we come across v in the way we add process information to the dialogue – what we’ve covered, validations, recognising the difficulties and qualities that has been demonstrated in the encounter v in the way that we ensure that when we leave, our final words communicate the impression we wanted to create v in the way that we follow-up the encounter and some issues covered in a letter, text, phone call, card (coloured envelope). It’s important to note that as human beings, we all yearn to be understood and remembered so again, this follow-up communication should embrace an emotional dimension and a sense of the meaning that has been shared

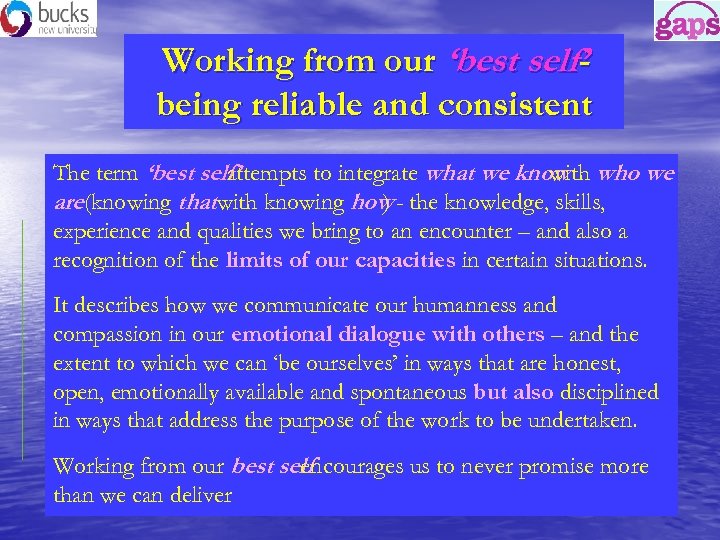

Working from our ‘best self’ being reliable and consistent The term ‘best self’ attempts to integrate what we know who we with are(knowing thatwith knowing how - the knowledge, skills, ) experience and qualities we bring to an encounter – and also a recognition of the limits of our capacities in certain situations. It describes how we communicate our humanness and compassion in our emotional dialogue with others – and the extent to which we can ‘be ourselves’ in ways that are honest, open, emotionally available and spontaneous but also disciplined in ways that address the purpose of the work to be undertaken. Working from our best self encourages us to never promise more than we can deliver

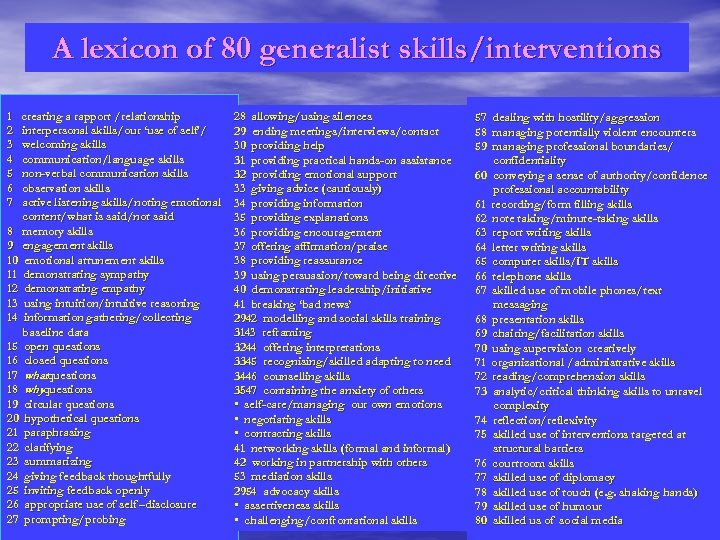

A lexicon of 80 generalist skills/interventions 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 creating a rapport /relationship interpersonal skills/our ‘use of self’/ welcoming skills communication/language skills non-verbal communication skills observation skills active listening skills/noting emotional content/what is said/not said 8 memory skills 9 engagement skills 10 emotional attunement skills 11 demonstrating sympathy 12 demonstrating empathy 13 using intuition/intuitive reasoning 14 information gathering/collecting baseline data 15 open questions 16 closed questions 17 whatquestions 18 whyquestions 19 circular questions 20 hypothetical questions 21 paraphrasing 22 clarifying 23 summarizing 24 giving feedback thoughtfully 25 inviting feedback openly 26 appropriate use of self –disclosure 27 prompting/probing 28 allowing/using silences 29 ending meetings/interviews/contact 30 providing help 31 providing practical hands-on assistance 32 providing emotional support 33 giving advice (cautiously) 34 providing information 35 providing explanations 36 providing encouragement 37 offering affirmation/praise 38 providing reassurance 39 using persuasion/toward being directive 40 demonstrating leadership/initiative 41 breaking ‘bad news’ 2942 modelling and social skills training 3143 reframing 3244 offering interpretations 3345 recognising/skilled adapting to need 3446 counselling skills 3547 containing the anxiety of others • self-care/managing our own emotions • negotiating skills • contracting skills 41 networking skills (formal and informal) 42 working in partnership with others 53 mediation skills 2954 advocacy skills • assertiveness skills • challenging/confrontational skills 57 dealing with hostility/aggression 58 managing potentially violent encounters 59 managing professional boundaries/ confidentiality 60 conveying a sense of authority/confidence professional accountability 61 recording/form filling skills 62 note taking/minute-taking skills taking/minute-taking 63 report writing skills 64 letter writing skills 65 computer skills/IT skills 66 telephone skills 67 skilled use of mobile phones/text messaging 68 presentation skills 69 chairing/facilitation skills 70 using supervision creatively 71 organizational /administrative skills 72 reading/comprehension skills 73 analytic/critical thinking skills to unravel complexity 74 reflection/reflexivity 75 skilled use of interventions targeted at structural barriers 76 courtroom skills 77 skilled use of diplomacy 78 skilled use of touch (e. g. shaking hands) 79 skilled use of humour 80 skilled us of social media

The relationship-based practice is central to the work of GAPS – a social work membership organisation set up in the 1970 s to promote therapeutic approaches, and psychosocial and systemic thinking in social work. Membership of GAPS cost £ 28. 00 pa for which subscribers receive 4 copies of the Journal of Social Work Practice. Information about events, papers and articles can be accessed free from the GAPS website http: //www. gaps. org. uk or by emailing GAPS info@gaps. org. uk Pamela Trevithick is the GAPS Coordinator trevithick 4 gaps@btinternet. com

REFERENCES England, H. (1986) Social Work as Art: Making Sense of Good Practice. London: Allen & Unwin. Lishman, J. (2009) Communication in Social Work, 2 nd edn. Basingstoke: Macmillan/BASW. Munro, E. (2011 b) The Munro Review of Child Protection: Final Report – A Child-Centred System. London: The Stationery Office. https: //www. gov. uk/government/publications/munro-review-of-child-protection-finalreport-a-child-centred-system [Accessed 19 Feb. 2014] Miller, J. B. (1986) What do we mean by relationships? Work in Progress #22. Wellesley, MA: Stone Center. Siegel, D. J. (2012) The Developing Mind: Toward a Neurobiology of Interpersonal Experience. 2 nd edn. New York: Guilford Press. Trevithick, P. (2003) ‘Effective relationship-based practice: a theoretical exploration’, Journal of Social Work Practice, Vol. 17: 173 -186. Trevithick, P. (2011) ‘Understanding defences and defensive behaviour in social work’, Journal of Social Work Practice, Vol. 25 (4): 389 -412. Trevithick, P. (2012) Social Work Skills and Knowledge: A Practice Handbook. 3 rd edn. Maidenhead: Open University Press. Trevithick, P. (2014) ‘Humanising managerialism: reclaiming emotional reasoning, intuition, the relationship, and knowledge and skills in social work’, Journal of Social Work Practice (forthcoming) Turnell, A. (2012) ‘Signs of safety: a comprehensive briefing paper’, Resolutions Consultancy, Perth. Available at: www. signsofsafety. net

58f1f38cb602566ea31ae8b9fae1d8a3.ppt