c91dfa26adf95a525f3fe6d14119f8d0.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 166

2011 INDIVIDUALTAX UPDATE © By Dennis J. Gerschick, Attorney, CPA, PFS, CFA

Dennis J. Gerschick Worked as a CPA in the tax dept. of Ernst & Whinney before law school and in the tax dept. of a large Atlanta law firm In 1990 Dennis started his own law firm www. gerschicklaw. com and also manages a wealth management firm. www. gerschick. com Dennis speaks frequently about a variety of topics. See www. Regal. Seminars. com

2010 Tax Legislation March 18 – Hiring Incentives to Restore Employment Act (the “HIRE Act”) In March, the health care reform, which included many tax provisions September 27, the Small Business Jobs Act December 17, the Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Jobs Creation Act of 2010

Prior Legislation Between December 2007 and December 2008, there were eight pieces of federal tax legislation The rules change fast! Look for applicable dates – starting and ending

Expected Tax Legislation To reduce the federal budget deficit, Congress may amend the tax code before December 31, 2011. After the November, 2012 elections, in 2013, more tax legislation is expected.

Where is Your Tax Home? Scroggins v Com’r, T. C. Memo. 2011 -103 (5 -18 -11) Issue: Whether petitioner husband’s tax home is in Georgia or California?

Where is Your Tax Home? Petitioners, on the Forms 1040, both indicate their home is in Warner Robins, Georgia. Petitioners filed California nonresident income tax returns for the 2004, 2005, and 2006 tax years and Georgia individual income tax returns for the 2004, 2005, and 2006 tax years. According to Mr. Scroggins’ bank records, Mr. Scroggins banked at Robins Federal Credit Union of Warner Robins, Georgia, throughout 2004 and used automatic teller machines (ATMs) in Florida from January through March 2004. Those records show that Mr. Scroggins used ATMs in California exclusively for the rest of 2004. Mr. Scroggins’ whereabouts are further explained by his 2004 Forms W-2, Wage and Tax Statement. In 2004 Mr. Scroggins received Forms W-2 from Huntington Beach Hospital in Huntington Beach, California, Crestview Hospital Corporation in Crestview, Florida, and Valley Presbyterian Hospital in Van Nuys, California. Mr. Scroggins’ 2005 ATM banking activities demonstrate that he was primarily in California. Not once did Mr. Scroggins use an ATM in Georgia.

Where is Your Tax Home? Deductions are a matter of legislative grace, and the taxpayer must maintain adequate records to substantiate the amounts of their income and entitlement to any deductions or credits claimed. INDOPCO, Inc. v. Commissioner, 503 U. S. 79, 84 (1992) Sec. 6001 (the taxpayer “shall keep such records”); sec. 1. 6001 -1(a), Income Tax Regs.

Where is Your Tax Home? In certain circumstances, the taxpayer must meet specific substantiation requirements to be allowed a deduction under section 162. See, e. g. , sec. 274(d). The heightened substantiation requirements of section 274(d) apply to: (1) Any traveling expense, including meals and lodging away from home (2) Any item with respect to an activity in the nature of entertainment, amusement, or recreation (3) Any expense for gifts (4) The use of “listed property”, as defined in section 280 F(d)(4), including any passenger automobiles.

Where is Your Tax Home? In order to deduct such expenses, the taxpayer must “substantiate by adequate records or by sufficient evidence corroborating the taxpayer’s own statement”: (1) The amount of the expense or other item (2) The time and place of the travel, entertainment, amusement, recreation, or use of the property (3) The business purpose of the expense or other item (4) The business relationship to the taxpayer of the persons entertained or receiving the described gift. Sec. 274(d).

Where is Your Tax Home? To satisfy the adequate records requirement of section 274, a taxpayer must maintain records and documentary evidence that in combination are sufficient to establish each element of an expenditure or use. Sec. 1. 274 -5 T(c)(1) and (2), Temporary Income Tax Regs. , 50 Fed. Reg. 4601646017 (Nov. 6, 1985). Although a contemporaneous log is not required, corroborative evidence created at or near the time of the expenditure to support a taxpayer’s reconstruction “of the elements * * * of the expenditure or use must have a high degree of probative value to elevate such statement” to the level of credibility of a contemporaneous record. Sec. 1. 2745 T(c)(1), Temporary Income Tax Regs. , supra.

Where is Your Tax Home? Most of the issues in this case stem from respondent’s determination that Mr. Scroggins’ tax home was in California for the years at issue. Claiming that Mr. Scroggins’ tax home was in Georgia, during the extended period he worked in California, petitioners deducted almost all of the living expenses he incurred for the 3 years at issue.

Travel Expenses In order to deduct travel expenses, petitioners must show that Mr. Scroggins’ expenses are ordinary and necessary, that he was away from home on business when he incurred the expense, and that the expense was incurred in pursuit of a trade or business. See sec. 162(a)(2); Commissioner v. Flowers, 326 U. S. 465, 470 (1946).

Where is Your Tax Home? The expenses in dispute were not incurred while Mr. Scroggins was away from his tax home. All three conditions discussed above must be satisfied for a taxpayer to be entitled to the deduction. Commissioner v. Flowers, supra at 470.

Where is Your Tax Home? This Court has interpreted a taxpayer’s “home” under section 162 to mean his principal place of employment and not where his personal residence is located. Mitchell v. Commissioner, 74 T. C. 578, 581 (1980); Daly v. Commissioner, 72 T. C. 190, 195 (1979), affd. 662 F. 2 d 253 (4 th Cir. 1981).

Where is Your Tax Home? However, we have also recognized an exception to this general rule in situations where the taxpayer is away from his home on a temporary rather than indefinite or permanent basis. Peurifoy v. Commissioner, 358 U. S. 59, 60 (1958). Petitioners assert that Mr. Scroggins falls within this exception.

Where is Your Tax Home? When a taxpayer seeks employment away from his personal residence, the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, to which this case is appealable, in Neal v. Commissioner, 681 F. 2 d 1157 (9 th Cir. 1982), affg. T. C. Memo. 1981 -407, explicitly adopted the following reasoning from Kasun v. United States, 671 F. 2 d 1059, 1061 (7 th Cir. 1982): While it is assumed that a person will live near the place of employment, it is not reasonable to expect people to move to a distant location when a job is foreseeably of limited duration. If, on the other hand, the prospect is that the work will continue for an indefinite or substantially long period of time, the travel expenses are not deductible.

Where is Your Tax Home? Mr. Scroggins was employed exclusively in California, with the exception of a short stint in Florida, for all of the years at issue. We need not separately determine whether, as may be the case, Mr. Scroggins was away from home while he was working in Florida and therefore possibly allowed to deduct those traveling expenses, because as discussed below, petitioners did not present any evidence to substantiate any of the expenses incurred. It was reasonably known to Mr. Scroggins that he would be employed for a very long time away from Georgia.

Where is Your Tax Home? Where spouses have careers in different locations, “Each must independently satisfy the requirement that deductions taken for travel expenses incurred in the pursuit of a trade or business arise while he or she is away from home. ” Hantzis v. Commissioner, 638 F. 2 d 248, 254 n. 11 (1 st Cir. 1981), revg. T. C. Memo. 1979 -299. Because we have found that Mr. Scroggins’ tax home was in California for the years at issue, he is not entitled to deduct any of his personal expenses for lodging or meals while in California.

Where is Your Tax Home? Petitioners are also not entitled to deduct Mr. Scroggins’ commuting costs in California. We note that generally taxpayers may not “deduct the daily cost of commuting to and from work, as such expense is considered to be personal and nondeductible. ” Brockman v. Commissioner, T. C. Memo. 2003 -3 (citing Commissioner v. Flowers, 326 U. S. at 473474).

Where is Your Tax Home? To satisfy section 274(d) petitioners must present sufficient evidence in addition to testimony to satisfy the three aspects of this requirement: (1) The amount, (2) the time and place, and (3) the business purpose of each expenditure. See sec. 1. 274 -5 T(b), Temporary Income Tax Regs. , 50 Fed. Reg. 46014 -46015 (Nov. 6, 1985). “ Congress has chosen to impose a rigorous test of deductibility in the area of travel expenses. Each of the foregoing elements must be proved for each separate expenditure.

Where is Your Tax Home? General vague proof, whether offered by testimony or documentary evidence, will not suffice. ” Smith v. Commissioner, 80 T. C. 1165, 1171 -1172 (1983). Evidence which is vague or significantly incomplete is not credible. Harris v. Commissioner, T. C. Memo. 2010 -248. Petitioners did not testify, there almost no receipts in evidence, and there is absolutely no explicit explanation of the business purpose of any of the expenditures.

Polling Question Since 2005, there has been: a. No tax legislation b. Many pieces of tax legislation c. No other significant developments d. No IRS action of any kind

IK vs. Employee Relevant factors include: (1) The degree of control exercised by the principal (2) Which party invests in the work facilities used by the worker (3) The opportunity of the individual for profit or loss (4) Whether the principal can discharge the individual (5) Whether the work is part of the principal’s regular business (6) The permanency of the relationship (7) Whether the worker is paid by the job or by the time (8) The relationship the parties believed they were creating (9) The provision of employee benefits. See Ewens & Miller, Inc. v. Commissioner, 117 T. C. 263, 270 (2001); De. Torres v. Commissioner, T. C. Memo. 1993 -161; see also 1 Restatement, Agency 2 d, sec. 220 (1958). We consider all of the facts and circumstances of each case, and no single factor is dispositive. Ewens & Miller, Inc. v. Commissioner, supra at 270.

IK vs. Employee The principal’s degree of control over the details of the taxpayer’s work is the most important factor in determining whether a common law employment relationship exists. See Clackamas Gastroenterology Associates, P. C. v. Wells, 538 U. S. 440, 448 (2003); Weber v. Commissioner, supra at 387. In an employer-employee relationship the principal must have the right to control not only the result of the employee’s work but also the means and method used to accomplish that result. Packard v. Commissioner, 63 T. C. 621, 629 (1975); Youngs v. Commissioner, T. C. Memo. 1995 -94, affd. without published opinion 98 F. 3 d 1348 (9 th Cir. 1996).

IK vs. Employee The degree of control necessary to find employee status varies according to the nature of the services provided. Weber v. Commissioner, supra at 387. Where the nature of the work is more independent, a lesser degree of control by the principal may still result in a finding of an employer employee relationship. Potter v. Commissioner, supra; Reece v. Commissioner, supra.

Gambling Mayo v. Com’r, 136 T. C. No. 4 (1 -25 -11) New law is made

Gambling P-H was engaged in the trade or business of gambling on horse races during 2001. Ps attached a Schedule C, Profit or Loss From Business, to their 2001 Federal income tax return, on which they reported the results of P-H’s gambling business, including gross receipts of $120, 463 and expenses of $142, 728, consisting of $131, 760 for wagers placed and $10, 968 in expenses incurred in connection with the conduct of the gambling business. Ps deducted the excess of the Schedule C expenses over gross receipts, $22, 265, as a business loss against their other income.

Gambling R issued a notice of deficiency disallowing $22, 265 of Ps’ claimed loss from gambling; i. e. , the amount by which expenses from P-H’s gambling activity exceeded gross receipts from gambling. R contends that Ps’ allowable losses from P-H’s gambling business are limited to the reported gross receipts from the business pursuant to I. R. C. sec. 165(d). R further maintains that the “Losses from wagering transactions” for purposes of I. R. C. sec. 165(d) include both the $131, 760 cost of wagers placed by P-H and the $10, 968 in expenses he incurred in connection with the conduct of the gambling business.

Gambling Issues are: (1) Whether petitioner’s engagement in the trade or business of gambling entitles him to deduct the losses from his gambling business from gross income without regard to section 165(d), which allows wagering losses only to the extent of wagering gains? (2) Whether petitioner is entitled to deduct the expenses, other than the costs of wagers, incurred in carrying on his gambling business pursuant to section 162(a) without regard to section 165(d)?

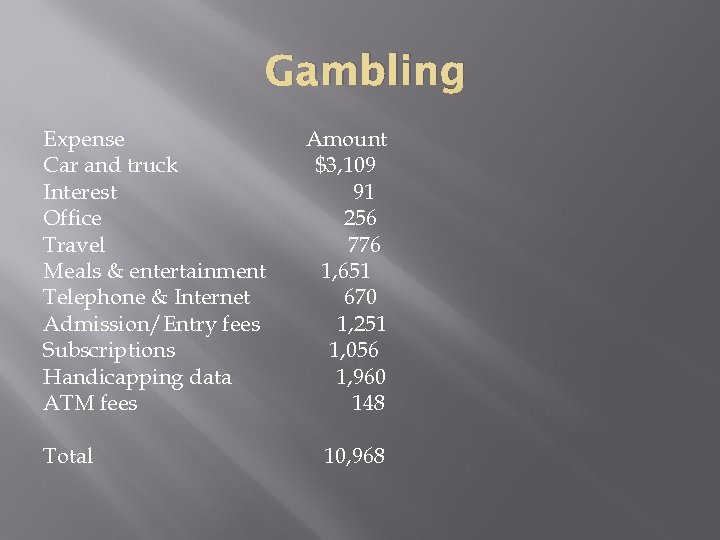

Gambling Expense Car and truck Interest Office Travel Meals & entertainment Telephone & Internet Admission/Entry fees Subscriptions Handicapping data ATM fees Total Amount $3, 109 91 256 776 1, 651 670 1, 251 1, 056 1, 960 148 10, 968

Gambling The parties have stipulated that petitioner was in the trade or business of gambling on horse races in 2001 and that he “wagered” a total of $131, 760 on the outcome of horse races and won a total of $120, 463 as a result of this wagering during that year. Petitioner’s wagering expenses thus come within the description of both section 162(a) and section 165(d). See, e. g. , Boyd v. United States, 762 F. 2 d 1369, 1372 -1373 (9 th Cir. 1985); Nitzberg v. Commissioner, 580 F. 2 d 357, 358 (9 th Cir. 1978), revg. T. C. Memo. 1975 -154 and T. C. Memo. 1975 -228; Offutt v. Commissioner, 16 T. C. 1214, 1215 (1951); Crawford v. Commissioner, T. C. Memo. 2010 -54; Valenti v. Commissioner, T. C. Memo. 1994 -483.

Gambling Petitioner contends that under Commissioner v. Groetzinger, 480 U. S. 23 (1987), the limitation of section 165(d) on the deduction of gambling losses does not apply to professional gamblers. Citing the Supreme Court’s observation that “basic concepts of fairness * * * demand that * * * [gambling] activity be regarded as a trade or business just as any other readily accepted activity”, id. at 33, petitioner contends that section 165(d) does not apply to an individual engaged in the trade or business of gambling since it does not apply to other trades or businesses.

Gambling In 1951 this Court considered whether an individual engaged in the trade or business of gambling is subject to the section 165(d) limitation on wagering losses, holding that the limitation applied in these circumstances. Offutt v. Commissioner, supra at 1215 -1216; accord Skeeles v. United States, 118 Ct. Cl. 362, 372, 95 F. Supp. 242, 246 -247 (1951).

Gambling In recent years we have repeatedly rejected the claim that Groetzinger modified this settled law and should be read as confining the application of section 165(d) to casual or recreational gamblers and eliminating the section’s limitation on the deduction of the gambling losses of professional gamblers. See Crawford v. Commissioner, supra; Lyle v. Commissioner, T. C. Memo. 1999 -184, affd. Without published opinion 218 F. 3 d 744 (5 th Cir. 2000); Valenti v. Commissioner, supra.

Gambling We must now decide whether the section 165(d) limitation on “Losses from wagering transactions” is confined to petitioner’s wagering expenses or extends to his business expenses, as the parties dispute the point. An implicit holding in Offutt is that a professional gambler’s “Losses from wagering transactions” for purposes of section 165(d) include amounts expended on wagers as well as other expenses incurred in carrying on the trade or business of gambling.

Gambling Neither the statute nor the regulations provide any definition of “Losses from wagering transactions” as used in section 165(d). The legislative history also provides no insight, as it does not address this specific point. Offutt offered no reasoning to support the conclusion that “Losses from wagering transactions” should be interpreted to cover both the cost of losing wagers as well as the more general expenses incurred in the conduct of a gambling business. Although Offutt’s interpretation of “Losses from wagering transactions” has generally been followed by this Court in the 60 years since the case was decided,

Gambling For the reasons discussed below, we conclude that reconsideration of Offutt’s interpretation of “Losses from wagering transactions” is warranted and that it should no longer be followed.

Gambling For the foregoing reasons, we conclude that the holding in Offutt v. Commissioner, supra, that “Losses from wagering transactions” include the trade or business expenses of a professional gambler other than the costs of wagers, should no longer be followed. We accordingly hold that petitioner is entitled to deduct under section 162(a) the $10, 968 in business expenses claimed in connection with carrying on his gambling business. Respondent has not argued that any of petitioner’s claimed business expenses were so integral to his wagers that they should be treated as part of the wagers’ cost. We leave any such issue for another day.

Gambling COLVIN, COHEN, THORNTON, MARVEL, GOEKE, WHERRY, KROUPA , HOLMES, GUSTAFSON, PARIS, and MORRISON, JJ. , agree with this opinion. HALPERN, J. , concurring: I agree with the result reached by the majority and write separately only to question the vitality of our Memorandum Opinion in Libutti v. Commissioner, T. C. Memo. 1996 -108,

Hobby Losses Section 183 Zenzen v. Com’r , T. C. Memo 2011 -167 (7 -12 -11) Drag Racing - Taxpayer lost Campbell v. Com’r, T. C. Memo 2011 -42 (2 -17 -11) Amway Distributorship – Taxpayer lost Blackwell v. Com’r, T. C. Memo 2011 -188 (8 -8 -11) Horse racing – Taxpayer won!

Polling Question Reading tax cases: a. Is a complete waste of time b. Shows that the IRS wins every time c. Is boring d. Is a great way to learn tax law

Section 183 – Hobby Loss Under section 183(a) and (b), if an activity is not engaged in for profit by a taxpayer the deductions claimed by the taxpayer relating to the activity are not allowed except to the extent of income received from the activity.

Section 183 To be treated as “engaged in for profit” an activity must be carried on by the taxpayer with an actual and honest profit objective. Dreicer v. Commissioner, 78 T. C. 642, 645 (1982), affd. without opinion 702 F. 2 d 1205 (D. C. Cir. 1983). Activities carried on primarily for sport, hobby, or recreation do not qualify as for-profit activities. Sec. 1. 183 -2(a), Income Tax Regs.

Section 183 – Hobby Loss Whether a taxpayer has the requisite profit objective with respect to an activity is a question of fact that is to be decided on the basis of all the evidence in a case. Generally, the taxpayer bears the burden of proving that he or she carried on the activity with a profit objective. Rule 142(a). In deciding this question, regulations under section 183 set forth a nonexclusive list of nine factors which generally are considered and which we discuss below. Sec. 1. 183 -2(b), Income Tax Regs.

Reg. 1. 183 -2(b) Factors 1. Manner in Which the Activity Is Carried On 2. Expertise of the Taxpayer 3. Time and Effort Expended in Carrying On the Activity 4. Expectation That the Horses May Appreciate in Value

Reg. 1. 183 -2(b) Factors 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Success in Other Activities History of Income or Losses Amount of Occasional Profits Financial Status Elements of Personal Pleasure

Divorce Taxation When a married couple divorces, many tax issues can arise. Who do you represent? Husband or wife?

Divorce Taxation Alimony is deductible by the payor and included in the taxable income of the recipient. See Sections 71 and 215 Child support is not deductible by the payor and not included in taxable income of the recipient. Property settlements? Generally carryover basis. See Section 1041

Alimony Moore v. Com’r, T. C. Memo. 2011 -200 (8 -16 -11) The sole issue for decision is whether payments of $21, 700. 82 petitioner made to his ex-wife in 2006 are deductible as alimony under section 215(a). Section 71(b)(1) defines alimony as any cash payment meeting the four criteria provided in subparagraphs (A) through (D) of that section.

Alimony SEC. 71(b). Alimony or Separate Maintenance Payments Defined. --For purposes of this section— (1) In general. --The term “alimony or separate maintenance payment” means any payment in cash if — (A) such payment is received by (or on behalf of) a spouse under a divorce or separation instrument, (B) the divorce or separation instrument does not designate such payment as a payment which is not includible in gross income under this section and not allowable as a deduction under section 215,

Alimony (C) in the case of an individual legally separated from his spouse under a decree of divorce or of separate maintenance, the payee spouse and the payor spouse are not members of the same household at the time such payment is made (D) there is no liability to make any such payment for any period after the death of the payee spouse and there is no liability to make any payment (in cash or property) as a substitute for such payments after the death of the payee spouse. Accordingly, if any portion of the payments made by petitioner fails to meet any one of the four enumerated criteria, that portion is not alimony and petitioner cannot deduct it.

Section 71(b)(1)(D) If the divorce instrument is silent as to the existence of a postdeath obligation, the requirements of section 71(b)(1)(D) may still be satisfied if the payments terminate upon the payee spouse’s death by operation of State law. Johanson v. Commissioner, supra at 977. If State law is ambiguous in this regard, however, a “federal court will not engage in complex, subjective inquiries under state law; rather, the court will read the divorce instrument and make its own determination based on the language of the document. ” Hoover v. Commissioner, 102 F. 3 d 842, 846 (6 th Cir. 1996), affg. T. C. Memo. 1995 -183.

Moore v. Com’r, T. C. Memo. 2011200 The divorce decree is silent as to whether petitioner’s obligation to reimburse Ms. Moore terminates in the event of Ms. Moore’s death. Thus, we consider whether the obligation to make payments terminates upon Ms. Moore’s death by operation of Indiana law. Indiana statutory law is silent as to whether the obligation to make maintenance payments terminates on the death of the payee spouse. The parties point us to no case law, and we have discovered none, that expressly states whether the obligation of maintenance terminates upon the death of the payee spouse.

Moore v. Com’r T. C. Memo. 2011, 200 No Indiana statute or opinion says that the payor’s obligation to pay alimony terminates upon the death of the payee spouse. Therefore, we conclude that Indiana law is ambiguous.

Moore v. Com’r T. C. Memo. 2011, 200 Finally, faced with a silent divorce decree and no State law resolution of the question, we independently review the decree to make our own determination as to the satisfaction of the section 71(b)(1)(D) requirement. See Hoover v. Commissioner, supra at 846. We do not read the decree as requiring the termination of payments in the event of Ms. Moore’s death. Hence, the payments do not satisfy the requirements of section 71(b)(1)(D), and petitioner is not entitled to deduct as alimony the $21, 700. 82 of payments to his wife in 2006.

Divorce Taxation Other tax issues: Who gets the tax exemption for the children? Who is liable for prior jointly filed tax returns? Does either spouse qualify for “innocent spouse” status?

Innocent Spouse Stephenson v. Com’r, T. C. Memo. 2011 -16 (1 -20 -11) Valarie Stephenson, pro se. Every “innocent spouse” case is fact intensive. Facts about education, life style, the relationship of the married couple, etc. What did they know and when did they know it? If they didn’t know taxes were owed, why not?

Innocent Spouse After the wedding Mr. Stephenson was stationed in Sacramento and petitioner remained in Phoenix to begin her junior year of high school. Three months into her junior year petitioner dropped out and moved to Sacramento to live with Mr. Stephenson. She never graduated from high school and has failed the General Education Development (GED) test three times. Petitioner also suffered from learning disabilities that forced her to be held back in elementary school. During their time in Sacramento Mr. Stephenson began verbally abusing petitioner, often making fun of her lack of education and learning disabilities in front of Mr. Stephenson’s family and their friends.

Innocent Spouse Petitioner and Mr. Stephenson lived in Dallas from 1999 until 2002. Mr. Stephenson worked as a stockbroker and day trader, and petitioner worked at a doctor’s office. Mr. Stephenson was highly successful, and he purchased a number of cars including a BMW that petitioner drove to work. They lived in three different condominiums during their time in Dallas

Innocent Spouse At all relevant times Mr. Stephenson managed the couple’s finances. Petitioner used a debit card to make household purchases. Most other purchases required Mr. Stephenson’s permission. He did not allow petitioner access to the mail box or to a filing cabinet that contained the checkbook and financial documents, both of which required a key that only Mr. Stephenson possessed. When Mr. Stephenson needed petitioner to sign something, he placed it in front of her and told her where to sign. If petitioner asked what she was signing, Mr. Stephenson made threats of violence or told her she was not intelligent enough to understand.

Innocent Spouse On January 11, 2008, petitioner filed Form 8857, Request for Innocent Spouse Relief, requesting relief from joint and several liability for the 1999 and 2004 tax years. Respondent granted petitioner’s request for innocent spouse relief for 2004. Respondent preliminarily denied petitioner’s request for relief for 1999 because it was untimely. The preliminary determination stated: “IRC section 6015 requires innocent spouse claims to be filed no later than two years after the date we start collection activity against you”.

Innocent Spouse In general, a spouse who files a joint Federal income tax return is jointly and severally liable for the entire tax liability. Sec. 6013(d)(3). However, a spouse may be relieved from joint and several liability under section 6015(f) if: (1) Taking into account all the facts and circumstances, it would be inequitable to hold her liable for any unpaid tax (2) Relief is not available to the spouse under section 6015(b) or (c).

Innocent Spouse The Commissioner has published revenue procedures listing the factors the Commissioner normally considers in determining whether section 6015(f) relief should be granted. See Rev. Proc. 2003 -61, 2003 -2 C. B. 296, superseding Rev. Proc. 2000 -15, 2000 -1 C. B. 447.

Polling Question Divorce taxation issues: a. Should always be handled by the divorce lawyers b. Should be decided by a flip of the coin c. Present a tax planning opportunity d. Are always decided by the divorce court

Innocent Spouse In determining whether petitioner is entitled to section 6015(f) relief we apply a de novo standard of review as well as a de novo scope of review. See Porter v. Commissioner, 132 T. C. 203 (2009); Porter v. Commissioner, 130 T. C. 115 (2008). Petitioner bears the burden of proving that she is entitled to relief. See Rule 142(a); Alt v. Commissioner, 119 T. C. 306, 311 (2002), affd. 101 Fed. Appx. 34 (6 th Cir. 2004).

Innocent Spouse In order for the Commissioner to determine that a taxpayer is eligible for section 6015(f) relief, the requesting spouse must satisfy the following threshold conditions: (1) She filed a joint return for the taxable year for which she seeks relief (2) Relief is not available to her under section 6015(b) or (c) (3) No assets were transferred between the spouses as part of a fraudulent scheme by the spouses (4) The nonrequesting spouse did not transfer disqualified assets to her (5) She did not file or fail to file the returns with fraudulent intent (6) With enumerated exceptions, the income tax liability from which she seeks relief is attributable to an item of the nonrequesting spouse. Rev. Proc. 2003 -61, sec. 4. 01, 2003 -2 C. B. at 297 -298.

Innocent Spouse We find, however, that the abuse exception in Rev. Proc. 2003 -61, sec. 4. 01(7)(d), applies. Mr. Stephenson abused petitioner throughout their marriage, and she did not question or disobey him for fear of abuse. If we find that petitioner is entitled to relief on the basis of these circumstances, it would be inequitable to hold her liable for the amount of the tax liability attributable to the income she earned. Accordingly, we find that petitioner has met the threshold criteria for relief as to the entire tax liability.

Innocent Spouse When the threshold conditions have been met, the Commissioner will ordinarily grant relief from an underpayment of tax if the requesting spouse meets the requirements set forth under Rev. Proc. 2003 -61, sec. 4. 02, 2003 -2 C. B. at 298.

Innocent Spouse To qualify for relief under Rev. Proc. 2003 -61, sec. 4. 02, the following elements must be satisfied: (1) On the date of the request for relief the requesting spouse is no longer married to, or is legally separated from, the nonrequesting spouse, or has not been a member of the same household as the nonrequesting spouse at any time during the 12 -month period ending on the date of the request for relief (2) On the date the requesting spouse signed the return she had no knowledge or reason to know that the nonrequesting spouse would not pay the income tax liability (3) The requesting spouse will suffer economic hardship if relief is not granted.

Innocent Spouse Where a requesting spouse meets the threshold conditions but fails to qualify for relief under Rev. Proc. 2003 -61, sec. 4. 02, a determination to grant relief may nevertheless be made under the criteria set forth in Rev. Proc. 2003 -61, sec. 4. 03, 2003 -2 C. B. at 298 -299. Rev. Proc. 2003 -61, sec. 4. 03, provides a nonexclusive list of factors the Commissioner will consider in making that determination.

Innocent Spouse In making our determination under section 6015(f), we shall consider the factors set forth in Rev. Proc. 2003 -61, sec. 4. 03, and any other relevant factors. No single factor is to be determinative in any particular case, and all factors are to be considered and weighed appropriately. See Haigh v. Commissioner, T. C. Memo. 2009 -140.

Innocent Spouse The Tax Court analyzed each of the factors. And noted: In summary, seven factors favor relief and one factor is neutral. After weighing the testimony and evidence in this fact intensive case, we conclude that it is inequitable to hold petitioner liable for the 1999 joint tax liability. Accordingly, we relieve petitioner from joint tax liability for tax year 1999.

Innocent Spouse There are many “innocent spouse” cases. See Thomassen v. Com’r, T. C. Memo 2011 -88 (4 -21011) Wife won.

Innocent Spouse Notice 2011 -70 Equitable Relief Under Section 6015(f) This notice expands the period within which individuals may request equitable relief from joint and several liability under section 6015(f) of the Internal Revenue Code. Specifically, this notice provides that the Internal Revenue Service will consider requests for equitable relief under section 6015(f) if the period of limitation on collection of taxes provided by section 6502 remains open for the tax years at issue. If the relief sought involves a refund of tax, then the period of limitation on credits or refunds provided in section 6511 will govern whether the IRS will consider the request for relief for purposes of determining whether a credit or refund may be available. This notice also provides certain transitional rules to implement this change.

Notice 2011 -70 Individuals may request equitable relief under section 6015(f) after the date of this notice without regard to when the first collection activity was taken. Requests must be filed within the period of limitation on collection in section 6502 or, for any credit or refund of tax, within the period of limitation in section 6511. The principal author of this notice is Stuart Murray of the Office of Associate Chief Counsel, Procedure and Administration. For further information regarding this notice, contact Stuart Murray at (202) 622 -4940 (not a toll-free number).

Polling Question New tax issues: a. Arise periodically and may be called an issue of “first impression” b. Are easy to resolve c. Never arise because taxes have been around forever d. Are best ignored

Sale of Annuities Estate of Kenneth L. Lay v. Com’r, T. C. Memo. 2011 -208 (829 -11) The status of the legal title to the annuity contracts does not control in determining whether a sale occurred. Beneficial ownership, and not legal title, determines ownership for Federal income tax purposes. Ragghianti v. Commissioner, 71 T. C. 346 (1978), affd. without published opinion 652 F. 2 d 65 (9 th Cir. 1981); Pac. Coast Music Jobbers, Inc. v. Commissioner, 55 T. C. 866, 874 (1971), affd. 457 F. 2 d 1165 (5 th Cir. 1972).

Sale of Property The Federal income tax consequences of property ownership generally depend upon beneficial ownership, rather than possession of mere legal title. Speca v. Commissioner, 630 F. 2 d 554, 556– 557 (7 th Cir. 1980), affg. T. C. Memo. 1979– 120; Beirne v. Commissioner, 61 T. C. 268, 277 (1973). “‘[C]ommand over property or enjoyment of its economic benefits’ * * *, which is the mark of true ownership, is a question of fact to be determined from all of the attendant facts and circumstances. ” Monahan v. Commissioner, 109 T. C. 235, 240 (1997) (quoting Hang v. Commissioner, 95 T. C. 74, 80 (1990)).

Sale of Property Beneficial ownership is marked by command over property or enjoyment of its economic benefits. Yelencsics v. Commissioner, 74 T. C. 1513, 1527 (1980) (stock was sold in accordance with an agreement for the sale, even though the title to the stock was not transferred, in accordance with the agreement of the parties).

Lays’ Sale of Annuities The Lays gave up all rights to alter or terminate the annuity contracts and lost domination and control over them. After selling the annuity contracts to Enron, the Lays could not sell them, nor could they liquidate them or borrow against them. They also could not alter the investment options for the annuity contracts or make any other elections or decisions regarding them. The Lays had delivered the transfer documents and received the consideration for the sale, and there was nothing else for them to do in connection with the transfer of the annuity contracts to Enron. The Lays, therefore, properly reported the transaction on their Federal income tax return as a sale of the two annuity contracts.

Estate of Kenneth L. Lay v. Com’r , T. C. Memo. 2011 -208 Respondent’s first alternative position is that the agreement provided for the transfer of the annuity contracts by Enron to the Lays on September 21, 2001, in connection with the performance of services by Mr. Lay and, therefore, caused the fair market value of the property to be taxable to Mr. Lay pursuant to section 83.

Section 83(a) provides, in pertinent part, that if property is transferred to a taxpayer in connection with the performance of services, the excess of the fair market value of the property over the amount, if any, paid for the property shall be included in the taxpayer’s gross income in the first taxable year in which the taxpayer’s rights in the property are not subject to a substantial risk of forfeiture. See Tanner v. Commissioner, 117 T. C. 237, 242 (2001), affd. 65 Fed. Appx. 508 (5 th Cir. 2003); sec. 1. 83 -7(a), Income Tax Regs.

Section 83 Taxability pursuant to section 83 would result only if the provision in the agreement that granted Mr. Lay the opportunity to earn back the Annuity contracts if he remained with Enron for a period of 4. 25 years (or an earlier date if Mr. Lay’s employment terminated for certain specified reasons beyond Mr. Lay’s control) constituted property that: (1) was transferred to Mr. Lay in 2001 (2) was in connection with his performance of services (3) was transferable by Mr. Lay or not subject to a substantial risk of forfeiture in 2001. See sec. 83(a).

Section 83 The promise in the agreement to reconvey the annuities to Mr. Lay after 4. 25 years of service, therefore, is not “property” within the meaning of section 83. Consequently, the threshold requirement for application of section 83 (that “property” be transferred to the service provider) is not met. This arrangement between Enron and Mr. Lay, for Enron to transfer property to Mr. Lay if he provided services for a period of years, is a nonqualified deferred compensation plan not taxed at inception because the property was not set aside or protected from the creditors of Enron. See sec. 83; sec. 1. 83 -3(e), Income Tax Regs.

Deferred Compensation Deferred compensation for services is included in gross income in the taxable year in which it is actually or constructively received. Sec. 1. 451 -1(a), Income Tax Regs. (income is included in income for the taxable year in which actually or constructively received by the taxpayer) Sec. 1. 446 -1(c)(1)(i), Income Tax Regs. (under the cash method of accounting, gross income is included for the taxable year in which actually or constructively received) Rev. Rul. 60 -31, 1960 -1 C. B. 174.

Deferred Compensation A mere promise to pay, not represented by notes or secured in any way, is not a receipt of income for a cash method taxpayer. Rev. Rul. 60 -31, 1960 -1 C. B. at 177. Income is constructively received in the taxable year in which it is credited to the taxpayer’s account or set apart for the taxpayer so that he may draw upon it at any time. Sproull v. Commissioner, 16 T. C. 244 (1951), affg. 194 F. 2 d 541 (6 th Cir. 1952); sec. 1. 451 -2, Income Tax Regs.

Deferred Compensation “However, income is not constructively received if the taxpayer’s control of its receipt is subject to substantial limitations or restrictions. ” Sec. 1. 451 -2(a), Income Tax Regs. Mr. Lay had no control over the annuity contracts in 2001. Enron’s listing the annuity contracts as assets when it filed for bankruptcy confirms that the annuity contracts were not set aside for Mr. Lay.

Section 83 requires inclusion of the fair market value of the property in income when the property is first either transferable or not subject to a substantial risk of forfeiture. Rights of a person in property are “transferable” if the person may transfer any interest in the property to any person other than the transferor, but only if the property is not subject to a substantial risk of forfeiture. Sec. 1. 83 -3(d), Income Tax Regs.

Section 83 Property is not considered to be transferable merely because the person performing the services may designate a beneficiary to receive the property in the event of his or her death. Sec. 1. 83 -3(d), Income Tax Regs.

Section 83 A substantial risk of forfeiture exists where the right to property is conditioned on the future performance of substantial services or the occurrence of a condition related to a purpose of the transfer, and the possibility of the forfeiture is substantial if such condition is not satisfied. Sec. 83(c); sec. 1. 83 -3(c)(1), Income Tax Regs. Forfeiture of property upon termination of employment before retirement at a specified age or time, death, or disability generally constitutes a substantial risk of forfeiture. Sec. 1. 83 -3(c)(4), Example (1), Income Tax Regs.

Estate of Kenneth L. Lay v. Com’r , T. C. Memo. 2011 -208 Forfeiture of the annuity contracts if Mr. Lay voluntarily terminated his employment before the 4. 25 years constitutes a substantial risk of forfeiture. See id. Because Mr. Lay had to work 4. 25 years for Enron in order to receive the annuity contracts and could terminate his employment before those 4. 25 years only under specific circumstances outside his control without forfeiting the annuity contracts, there was a “substantial risk of forfeiture” in 2001. The events in 2002 regarding Mr. Lay’s resignation are not before us. In conclusion, section 83 does not apply to the deferred compensation arrangement at issue.

Estate of Kenneth L. Lay v. Com’r , T. C. Memo. 2011 -208 Respondent’s second alternative position is that the $10 million purchase price Enron paid for the annuity contracts was in excess of their fair market value as of September 21, 2001, and that the excess represented additional compensation to Mr. Lay. There is nothing in the record to indicate that any portion of the $10 million that Enron paid the Lays for the annuity contracts represented a premium or additional amount in excess of the fair market value of the annuity contracts that would otherwise constitute compensation

Estate of Kenneth L. Lay v. Com’r , Nevertheless, the Compensation Committee reasonably found that $10 million was a fair price for the annuity contracts. The issue is not whether the value of the annuity contracts was, in fact, $10 million. The issue is whether the $10 million that Enron paid to the Lays was intended for the purchase of the annuity contracts. In determining whether the annuities transaction was in fact a sale, the Court considers whether the purchase price was within a reasonable range. See Commissioner v. Brown, 380 U. S. at 572.

Polling Question Ken Lay’s Estate: a. Lost because the Court was upset Enron failed b. Lost because the Court assumed fraud was involved c. Won because it had the facts and law on its side d. Lost because the judge owned Enron stock

Sale of Tax Credits Tempel v. Com’r, 136 T. C. No. 15 (4 -5 -11) In 2004 Ps donated a qualified conservation easement to a qualified charitable organization. As a result, Ps received conservation easement income tax credits from the State of Colorado. These credits were transferable to other taxpayers. That same year Ps sold a portion of those credits. Ps reported short-term capital gains from the sales of the State credits. Ps claimed an allocated portion of the professional fees they incurred to complete the conservation easement donation, as adjusted basis in the State tax credits they sold. R determined the State income tax credits that Ps sold were not capital assets and that Ps had no adjusted basis in the credits.

Sale of Tax Credits Capital gains are derived from the sale or exchange of capital assets. Sec. 1222. Section 1221 defines “capital asset” as held by a taxpayer, except for eight categories of property specifically excluded from the definition.

What is a Capital Asset? SEC. 1221. CAPITAL ASSET DEFINED. In General. –-For purposes of this subtitle, the term “capital asset” means property held by the taxpayer (whether or not connected with his trade or business), but does not include: (1) stock in trade of the taxpayer or other property of a kind which would properly be included in the inventory (2) property, used in his trade or business, of a character which is subject to the allowance for depreciation provided in section 167, or real property used in his trade or business (3) a copyright, a literary, musical, or artistic composition (4) accounts or notes receivable acquired in the ordinary course of trade or business (5) a publication of the United States Government (6) any commodities derivative financial instrument held by a commodities derivatives dealer, unless (7) any hedging transaction (8) supplies of a type regularly used or consumed by the taxpayer in the ordinary course of a trade or business of the taxpayer.

Tempel v. Com’r 136 T. C. No. 15 , None of the excluded categories is applicable to the State tax credits at issue. There is “no single definitive” definition of a capital asset. Gladden v. Commissioner, 112 T. C. 209, 218 (1999), revd. on a different issue 262 F. 3 d 851 (9 th Cir. 2001). Instead, it is a very broad term. As the Supreme Court observed: The body of § 1221 establishes a general definition of the term “capital asset, ” and the phrase “does not include” takes out of that broad definition only the classes of property that are specifically mentioned. *** * * * Ark. Best Corp. v. Commissioner, 485 U. S. 212, 218 (1988).

What is a Capital Asset? Faced with determining the character of assets that do not fit any of the section 1221 exceptions to the definition of a capital asset yet do not appear to properly fit that of a capital asset, courts use the substitute for ordinary income doctrine to exclude certain property. See Lattera v. Commissioner, 437 F. 3 d 399, 402 -403 (3 d Cir. 2006), affg. T. C. Memo. 2004 -216. Under this doctrine, “capital asset” does not include mere rights to receive ordinary income. Commissioner v. P. G. Lake, Inc. , 356 U. S. 260, 265 -266 (1958). The practical effect of the substitute for ordinary income doctrine is that the Supreme Court “has consistently construed ‘capital asset’ to exclude property representing income items or accretions to the value of a capital asset themselves properly attributable to income. ” United States v. Midland-Ross Corp. , 381 U. S. 54, 57 (1965).

What is a Capital Asset? The doctrine has been applied by courts directly and indirectly to exclude a variety of assets from the breadth of section 1221. Watkins v. Commissioner, 447 F. 3 d 1269, 1273 (10 th Cir. 2006) (treating the transfer of rights to lottery payments as ordinary income), affg. T. C. Memo. 2004 -244; Saviano v. Commissioner, 765 F. 2 d 643, 653 -654 (7 th Cir. 1985) (holding that the sale of a “gold option” did not result in capital gains when the option represented a right of first refusal to net profits from mining), affg. 80 T. C. 955 (1983); Freese v. United States, 455 F. 2 d 1146, 1152 (10 th Cir. 1972) (determining that a settlement payment was a substitute for the taxpayer’s services as an employee); Hallcraft Homes, Inc. v. Commissioner, 336 F. 2 d 701, 705 (9 th Cir. 1964)

What is a Capital Asset? (finding sale of water refund agreements resulted in ordinary income), affg. 40 T. C. 199 (1963); Bisbee -Baldwin Corp. v. Tomlinson, 320 F. 2 d 929, 936 (5 th Cir. 1963) (treating consideration for mortgage servicing contracts as a substitute for commissions); Dyer v. Commissioner, 294 F. 2 d 123, 126 (10 th Cir. 1961) (finding sale of fractional interests in mineral leaseholds was a substitute for future income), affg. 34 T. C. 513 (1960); Forrer v. Commissioner, T. C. Memo. 1981 -418 (concluding that assignment of rights to book royalties was a transfer of an ordinary income asset).

Capital Asset? It is also apparent that the transferred State tax credits never represented a right to receive income from the state. Instead, they merely represented the right to reduce a taxpayer’s State tax liability. It is without question that a government’s decision to tax one taxpayer at a lower rate than another taxpayer is not income to the taxpayer who pays lower taxes. A lesser tax detriment to a taxpayer is not an accession to wealth and therefore does not give rise to income. All “accessions to wealth, clearly realized, and over which the taxpayers have complete dominion” are income. Commissioner v. Glenshaw Glass Co. , 348 U. S. 426, 431 (1955).

Tempel v. Com’r 136 T. C. No. 15 , None of the categories of property in section 1221 that Congress specifically excepted from the term capital asset is applicable to the State tax credits. Accordingly, we hold the State tax credits petitioners sold are capital assets.

Basis of the tax credits? Section 1012 sets forth the foundational principle that the basis of property for tax purposes shall be the cost of the property. Cost, in turn, is defined by regulation as the amount paid for the property in cash or other property. Sec. 1. 1012 -1(a), Income Tax Regs.

Basis in the tax credits? Petitioners argue that they have a cost basis in their State tax credits. On their tax return they claimed a cost basis in the credits based upon an allocation of $11, 574. 74 of professional fees they incurred in connection with establishing and donating the conservation easement. The fees consisted of accounting, appraisal, surveying, and other professional services. In their cross-motion for partial summary judgment petitioners appear also to argue some portion of their basis in their land should be allocable to the State tax credits. While petitioners did not raise their position in their pleadings, raising it in their motion has not prejudiced respondent. We find neither position tenable.

Tax basis of tax credits? Petitioners paid transaction fees to establish a conservation easement that they donated to an unrelated third party. Petitioners did not acquire the State tax credits by purchase. This Court also notes that it has previously declined to adopt the “unusual concept that cost basis can be allocated to property other than * * * property purchased. ” Solitron Devices, Inc. v. Commissioner, 80 T. C. 1, 17 (1988), affd. without published opinion 744 F. 2 d 95 (11 th Cir. 1984).

Basis of tax credits? These credits are not a right petitioners possessed in their land. Instead, their rights in the credits, although achieved because of the property, arose on account of the grant from the State. Unlike the easement granted in Fasken v. Commissioner, supra, the State tax credits are not a property right in land that would necessitate the allocation of basis in the land to the credits. We conclude petitioners do not have any basis in their State tax credits.

Holding period of tax credits? Petitioners’ holding period in their credits began at the time the credits were granted and ended when petitioners sold them. Since petitioners sold their State tax credits in the same month in which they received them, the capital gains from the sale of the credits are short term

Polling Question The sale of tax credits is: a. Produces tax-exempt income b. Voids the tax credits because they are not transferable c. Should never be done d. Is done and gets capital gain treatment

Worthless Stock Bengtson v. Com’r, T. C. Memo 2011 -50 (3 -1 -11) In the late 1990 s petitioners agreed with Joan Thomley, Mrs. Bengtson’s sister, to invest in stocks. In 1999, 2000, and 2001, petitioners provided funds to Mrs. Thomley, who in turn purchases stock in Maintenance Depot, Inc. (Maintenance), Sideware, Inc. (Sideware), and other companies. Mrs. Thomley made the purchases through her brokerage account, and all shares were purchased and held in her name.

Worthless Stock In 2000, Mrs. Thomley informed petitioners that her 1999 stock transactions had resulted in a taxable gain, asked petitioners for money to pay the taxes relating to the transactions, and told petitioners that the proceeds of the transactions would be reinvested.

Worthless Stock Maintenance in 2001 was taken off the exchange on which it was traded and in 2005 repurchased its outstanding shares. In 2003, Sideware sold its assets and ceased operations. On their 2005 joint Federal income tax return (2005 return), petitioners reported a long-term capital loss relating to 29, 488 shares of Maintenance and 3, 680 shares of Sideware. Petitioners also reported a long-term capital gain relating to the exercise of International Business Machines Corp. stock options. Respondent began an audit of petitioners’ 2005 return in 2007. During the audit, respondent asserted that the Maintenance and Sideware stocks became worthless in 2001 and 2002.

Worthless Stock Section 165 (g) allows a deduction for any loss resulting from stock that becomes worthless during the taxable year. A taxpayer must, however, maintain sufficient records to substantiate the loss. Sec. 6001; Reg. 1. 6001 -1 (a). There is insufficient evidence in the record to establish the ownership, bases, and dates of worthlessness relating to the Maintenance and Sideware stocks for which petitioners claiming a long-term capital loss. Accordingly, petitioners are not entitled to deduct a loss relating to the stocks.

Estate Planning Changes On December 17, 2010, President Obama signed the “Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010” (the “ 2010 Act”). The 2010 Act made significant changes affecting the estate and gift tax laws.

Estate Planning Changes The 2010 Act sets the estate, gift and generationskipping tax exemption at $5 mil for each tax. The $5 mil is indexed beginning in 2012. The $5 mil estate tax exemption also applies for 2010 but the gift tax exemption for 2010 remained at $1 million. The maximum rate is 35%.

2010 Decedents No estate tax in 2010 The executors of estates of decedents who died in 2010 may elect to use either: (1) the $5 mil exemption with step-up in basis rules, or (2) no estate tax but use the modified basis rules of Code § 1022.

2010 Decedents IRS Form 8939 for Decedents Who Died in 2010 Notice 2011 -76, IRB 2011 -40, dated October 3, 2011. This notice applies to each Executor of a 2010 Estate and to recipients of property acquired from decedents who died in 2010.

Notice 2011 -76 Section 301(c) of TRUIRJCA, however, allows the Executor of a 2010 Estate to elect not to have the estate tax provisions and section 1014 apply, but rather, to have the provisions of section 1022 apply (Section 1022 Election). With the election, the estate will pay no estate tax and in most cases the basis of the property acquired from the decedent will be determined under section 1022. In addition, the executor may allocate additional basis to certain property. See Rev. Proc. 2011 -41, 2011 -35 I. R. B. 188.

Notice 2011 -76 The due date for filing Form 8939 is changed from November 15, 2011, to January 17, 2012. Thus, a Section 1022 Election is timely if made on a Form 8939 filed by (and may be amended or revoked on or before) January 17, 2012. The Treasury Department and IRS will not grant any further extension of time to file Form 8939, to make the Section 1022 Election, or to amend or revoke the Section 1022 Election, except as provided in sections I. A, B, or D. 1 or 2 of Notice 2011 -66.

Notice 2011 -76 This notice is effective on September 13, 2011. This notice applies to each Executor of a 2010 Estate and to persons acquiring property from a 2010 Decedent. The principal authors of this notice are Laura Daly, Theresa Melchiorre, and Mayer Samuels of the Office of Associate Chief Counsel (Passthroughs & Special Industries). For further information regarding this notice contact Laura Daly, Theresa Melchiorre, or Mayer Samuels on (202) 6223090 (not a toll-free call).

Big Change The 2010 Act creates the “portability concept. ” Code § 2010(c) is amended to provide that the estate tax exclusion amount is equal to: (1) the basic exclusion amount ($5 mil as indexed), plus (2) for a surviving spouse, the “deceased spousal unused exclusion amount” (DESUEA).

Portability Concept The DESUEA is the lesser of: (1)the basic exclusion amount or (2) the basic exclusion amount of the surviving spouse’s last deceased spouse over the combined amount of the deceased spouse’s taxable estate plus adjusted taxable gifts (described in new Code § 2010(c)(4)(B)(ii)).

Portability Concept The second item is the last deceased spouse’s remaining unused exemption amount. There appears to be a strict privity requirement. A spouse may not use his or her spouse’s DESUEA. Example: assume H 1 dies and W has his DESUEA. Assume W remarries H 2. If W dies before H 2, H 2 may then use the DESUEA from W’s unused basic exclusion amount, but may not use any of H 1’s unused exclusion amount.

Portability Concept The executor of the first deceased spouse’s estate must file an estate tax return on a timely basis and make an election to permit the surviving spouse to utilize the unused exemption amount. Only the most recent deceased spouse’s unused exemption may be used by the surviving spouse. See Code § 2010(c)(5)(B)(i). The portability concept applies to the gift tax too.

Important Point The new estate and gift tax laws are effective for only 2011 and 2012. Then we are back to uncertainty. If no further change is made, we go back to the 2001 law.

Planning Questions Do gifts make sense if the estate tax exemption is increased further? Gifts may remove the post-gift appreciation in value from the estate Gifts may allow the use of valuation discounts If the donor lives three years after the gift, the gift taxes paid are removed from the gross estate How much can/should the donors gift away?

Changes Not Made The new law did not change family limited partnerships or family LLCs The new law did not change GRATs (there is no minimum 10 year term) Irrevocable life insurance trusts are still viable

Everyone Should: Review their current financial position and consider likely future changes Review their existing estate plan (Wills, trusts, etc. ) Consider what changes, if any, should be made

Polling Question Estate planning: a. Has always been easy and will continue to be b. Is no longer needed c. Should be considered by everyone d. Is null and void due to recent changes in the law

Family Limited Partnership Estate of Turner v. Com’r, T. C. Memo. 2011 -209 (830 -11) Another fact intensive case The taxpayer lost due to several mistakes

Estate of Turner v. Com’r On April 15, 2002, Clyde Sr. and Jewell established Turner & Co. as a Georgia limited liability partnership by filing a certificate of limited partnership. The Agreement of Limited Partnership of Turner & Company, L. P. (partnership agreement), provided that Clyde Sr. and Jewell each would own a 0. 5 -percent general partnership interest and a 49. 5 -percent limited partnership interest. After Clyde Sr. ’s death, the Turner family held meetings, on November 5, 2004, and November 19, 2005, to discuss Turner & Co. ’s past performance and future investment plans. The meetings also included discussions of Clyde Sr. ’s estate and the provisions of his will. The record is not clear whether the Turner family held any meetings to discuss Turner & Co. ’s performance before Clyde Sr. ’s death. Although Marc and Betty suggested they did, no objective evidence corroborates their statements.

Estate of Turner v. Com’r In 2002 Clyde Sr. and Jewell each contributed assets to Turner & Co. with a fair market value of $4, 333, 671 (total value $8, 667, 342). The list of assets to be contributed was not finalized until at least July 2002, and the transfers were not completed until at least December 2002. The contributed assets consisted of cash, CDs, and stocks. Clyde Sr. and Jewell did not contribute to Turner & Co. any interest in an operating business or in a regularly conducted real estate activity that required active management.

Estate of Turner v. Com’r Clyde Sr. and Jewell retained more than $2 million of assets that were not contributed to Turner & Co. , including but not limited to their residence in Cleveland, Georgia, investment real estate in North Carolina, cash and certificates of deposit, and 24, 012 shares of Regions Bank stock. The retained assets, together with Social Security income, generated annual income of at least $90, 000 --more than enough to pay Clyde Sr. and Jewell’s living expenses.

Estate of Turner v. Com’r The partnership agreement listed three general purposes for creation of Turner & Co. : (1) To make a profit (2) To increase the family’s wealth (3) To provide a means whereby family members can become more knowledgeable about the management and preservation of the family’s assets. To facilitate the general purposes, the partnership agreement listed nine specific purposes formation of Turner & Co.

Estate of Turner v. Com’r The partnership agreement was modeled on a standard form that Stewart, Melvin & Frost used when drafting partnership agreements. Consequently, some of the purposes listed in the partnership agreement did not apply to the Turner family. (For example, the partnership agreement provides that one of the goals of the partnership is to consolidate or eliminate fractional interests in realty. However, Clyde Sr. and Jewell did not contribute any interests in real property, fractional or otherwise, to Turner & Co. ) Clyde Sr. and Jewell’s actual purposes for establishing Turner & Co. were not necessarily reflected in the partnership agreement.

Estate of Turner v. Com’r The Tax Court analyzed the partnership agreement noting many specific provisions

Estate of Turner v. Com’r On December 31, 2002, and January 1, 2003, Clyde Sr. and Jewell gave limited partnership interests in Turner & Co. to their three children and to Joyce’s children. According to the gift transfer documents, the aggregate fair market values of the partnership interests transferred on December 31, 2002, and January 1, 2003, were $1, 652, 315 and $474, 315, respectively. The values were derived from a valuation by Willis Investment Counsel dated May 18, 2004, and were added to the gift transfer documents on or after that date.

Estate of Turner v. Com’r Turner & Co. made several payments to Clyde Sr. in 2002 a total of $41, 500. Turner & Co. did not make any payments to Jewell in her capacity either as a general partner or as a limited partner, or to any other limited partner in 2002. Turner & Co. made many payments to Clyde Sr. and Jewell in 2003, a total of $86, 815. Turner & Co. did not make any payments to any other limited partners in 2003.

Estate of Turner v. Com’r The purpose of section 2036(a) is to include in a decedent’s gross estate the values of inter vivos transfers that were “essentially testamentary” in nature. See United States v. Estate of Grace, 395 U. S. 316, 320 (1969) (interpreting section 811(c)(1)(B) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1939, a predecessor to section 2036).

Estate of Turner v. Com’r Section 2036(a) applies when three conditions are satisfied: (1) The decedent made an inter vivos transfer of property, (2) The decedent’s transfer was not a bona fide sale for adequate and full consideration (3) The decedent retained an interest or right enumerated in section 2036(a)(1) or (2) or (b) in the transferred property that he did not relinquish before his death. Sec. 2036(a); Estate of Bongard v. Commissioner, 124 T. C. 95, 112 (2005). If these conditions are met, the full value of the transferred property is included in the value of the decedent’s gross estate. Estate of Bongard v. Commissioner, supra at 112.

Estate of Turner v. Com’r In the context of a family limited partnership the bona fide sale exception is satisfied where the record establishes the existence of a legitimate and significant nontax reason for creation of the family limited partnership and the transferors received partnership interests proportionate to the value of the property transferred. Estate of Bongard v. Commissioner, supra at 118 (citing Estate of Stone v. Commissioner, T. C. Memo. 2003 -309, and Estate of Harrison v. Commissioner, T. C. Memo. 1987 -8). The objective evidence must establish that the nontax reason was a significant factor that motivated the partnership’s creation. See id. ; Estate of Harper v. Commissioner, supra; Estate of Harrison v. Commissioner, supra. “A significant purpose must be an actual motivation, not a theoretical justification. ” Estate of Bongard v. Commissioner, supra at 118.

Estate of Turner v. Com’r Whether a sale is bona fide is a question of motive. We must determine whether the record supports a finding that Clyde Sr. had a legitimate and significant nontax reason forming Turner & Co.

Estate of Turner v. Com’r The Turner & Co. partnership agreement lists three general reasons and nine specific reasons for the formation of the partnership. However, the reasons listed in the partnership agreement were taken from a form partnership agreement and do not necessarily reflect Clyde Sr. and Jewell’s actual reasons for establishing Turner & Co. For example, the partnership agreement states that one of the purposes of Turner & Co. was to consolidate or eliminate fractional interests in realty and other family assets. In fact, Clyde Sr. and Jewell did not contribute any real property to Turner & Co. , and all of the contributed property was easily divisible. In any event, we do not simply rely on a list of reasons. See Estate of Hurford v. Commissioner, T. C. Memo. 2008 -278. Instead, we examine the evidence to see whether any of the asserted nontax reasons was a significant factor in creating the partnership. See id.

Estate of Turner v. Com’r Petitioner argues that Clyde Sr. and Jewell created Turner & Co. for at least one of the following legitimate and significant nontax reasons The objective facts in the record fail to establish that any of these reasons was a legitimate and significant reason formation of Turner & Co.

Estate of Turner v. Com’r Consolidated asset management may be a legitimate and significant nontax purpose. Estate of Schutt v. Commissioner, T. C. Memo. 2005 -126; see also Estate of Black v. Commissioner, 133 T. C. 340, 371 (2009). However, consolidated asset management generally is not a significant nontax purpose where a family limited partnership is “just a vehicle for changing the form of the investment in the assets, a mere asset container. ” Estate of Erickson v. Commissioner, T. C. Memo. 2007 -107; see also Estate of Schutt v. Commissioner, supra (“the mere holding of an untraded portfolio of marketable securities weighs negatively in the assessment of potential nontax benefits available as a result of a transfer to a family entity” (citing Estate of Thompson v. Commissioner, 382 F. 3 d 367, 380 (3 d Cir. 2004))) Estate of Harper v. Commissioner, supra (“Without any change whatsoever in the underlying pool of assets or prospect for profit * * * there exists nothing but a circuitous ‘recycling’ of value. ”).

Estate of Turner v. Com’r Most of the cases in which we have held that consolidated asset management is a legitimate nontax purpose have involved assets requiring active management or special protection. Estate of Black v. Commissioner, supra at 371 (large bloc of voting stock in closely held corporation) Estate of Mirowski v. Commissioner, T. C. Memo. 2008 -74 (patent royalties and related investments) Estate of Stone v. Commissioner, supra (closely held business); see also Kimbell v. United States, 371 F. 3 d 257 (5 th Cir. 2004) (working oil and gas interests).

Estate of Turner v. Com’r Clyde Sr. and Jewell owned passive investments rather than a business requiring active management. Petitioner does not dispute that Clyde Sr. and Jewell contributed only passive assets to Turner & Co. Unlike the partnership assets involved in Estate of Mirowski v. Commissioner, supra, and Estate of Stone v. Commissioner, T. C. Memo. 2003 -309, the Turner & Co. assets required no active management or special protection. Moreover, unlike the decedents in those cases, Clyde Sr. did not have a unique or distinct investment philosophy that he hoped to perpetuate.

Estate of Turner v. Com’r In reaching our conclusion that asset management was not a significant nontax purpose, we rely on our finding that Turner & Co. ’s portfolio of marketable securities did not change in a meaningful way. Regents Bank stock continued to dominate the portfolio from the time of the partnership formation until Clyde Sr. ’s death. Whatever assets Turner & Co. added to the portfolio had a risk/return profile similar to the profile of the assets Clyde Sr. and Jewell contributed to the partnership.

Estate of Turner v. Com’r Several additional factors indicate that the transfers to Turner & Co. were not bona fide sales. First, Clyde Sr. stood on both sides of the transaction, and he created Turner & Co. without any meaningful bargaining or negotiation with Jewell or with any of the other anticipated limited partners; i. e. , his children and grandchildren. See Estate of Harper v. Commissioner, T. C. Memo. 2002121.

Estate of Turner v. Com’r Second, Clyde Sr. commingled personal and partnership funds when he used partnership funds to make personal gifts to Marc and Travis, to pay premiums on life insurance policies for the benefit of his children and grandchildren, and to pay legal fees relating to his and Jewell’s estate planning.

Estate of Turner v. Com’r Third, Clyde Sr. and Jewell did not complete the transfer of assets to Turner & Co. for at least 8 months after formation of the partnership. Petitioner argues that it took longer than expected for Clyde Sr. and Jewell to transfer their assets to Turner & Co. because of poor recordkeeping on their part. However, at the time Turner & Co. was formed Marc had been assisting Clyde Sr. and Jewell with their recordkeeping for approximately 8 years (since 1994 according to Marc’s testimony). Thus, any delays in transferring assets to Turner & Co. cannot be blamed on Clyde Sr. ’s and Jewell’s poor recordkeeping. See Estate of Hurford v. Commissioner, T. C. Memo. 2008 -278 Estate of Bigelow v. Commissioner, T. C. Memo. 2005 -65, affd. 503 F. 3 d 955 (9 th Cir. 2007) Estate of Harper v. Commissioner, supra.

Estate of Turner v. Com’r On the basis of the foregoing, we conclude that the formation of Turner & Co. falls short of meeting the bona fide sale exception. Rather, Clyde Sr. changed the form in which he held the interest in the contributed assets, and the formation of Turner & Co. was a part of a testamentary plan. Accordingly, the bona fide sale exception of section 2036(a) does not apply to Clyde Sr. ’s transfer of property to Turner & Co. We therefore consider whether Clyde Sr. retained for his life the possession or enjoyment of the transferred property.

Estate of Turner v. Com’r Factors indicating that a decedent retained an interest in transferred assets under section 2036(a)(1) include a transfer of most of the decedent’s assets, continued use of transferred property, commingling of personal and partnership assets, disproportionate distributions to the transferor, use of entity funds for personal expenses, and testamentary characteristics of the arrangement. Estate of Gore v. Commissioner, T. C. Memo. 2007 -169 Estate of Erickson v. Commissioner, supra (citing Estate of Rosen v. Commissioner, T. C. Memo. 2006 -115 , Estate of Harper v. Commissioner, supra). The taxpayer bears the burden, which is especially onerous in transactions involving family members, of proving that an implied agreement did not exist. Estate of Reichardt v. Commissioner, supra at 151 -152.

Estate of Turner v. Com’r We turn to the record and examine it for what it shows about Clyde Sr. ’s possession and enjoyment of the assets he transferred to Turner & Co. We start with the partnership agreement. The partnership agreement expressly provides that the general partner is entitled to a “reasonable” management fee, and Clyde Sr. and/or Jewell chose to receive a management fee of $2, 000 per month without any apparent regard for the nature and scope of their actual management duties. There is nothing in the record to suggest that a $2, 000 management fee was reasonable. The record does not disclose what, if anything, Clyde Sr. and Jewell did to manage the partnership. In fact, some of the evidence suggests that Clyde Sr. and Jewell did not manage the partnership at all.

Estate of Turner v. Com’r We turn now to an examination of the factors that tend to show an agreement to retain possession and enjoyment of the transferred assets. Nearly all of the facts point to an implied agreement. Clyde Sr. transferred most of his assets to Turner & Co. Nearly 60 percent of the value of all property that Clyde Sr. and Jewell contributed to Turner & Co. consisted of Regions Bank common stock. Because of his and Jewell’s sentimental attachment to the Regions Bank stock, Turner & Co. did not sell the Regions Bank stock. Although he and Jewell retained sufficient assets outside of the partnership to meet their living expenses, they opted to receive management fees from Turner & Co. for few or no management services and took distributions from Turner & Co. at will.

Estate of Turner v. Com’r Most importantly, contrary to petitioner’s assertions, we find that the purpose of Turner & Co. was primarily testamentary. When Clyde Sr. purportedly approached Marc about creating a vehicle to consolidate his assets, he allegedly stated that he and Jewell were not getting any younger. Petitioner’s own witnesses testified that when Clyde Sr. met with attorneys at Stewart, Melvin & Frost, he said that he wanted to discuss estate planning. Many of the specific purposes Clyde Sr. purportedly outlined at the meeting were testamentary, e. g. , providing for Jewell after his death, providing income for future generations, and protecting his children and grandchildren from creditors.

Estate of Turner v. Com’r We are particularly struck by the implausibility of petitioner’s assertion that tax savings resulting from the family limited partnership were never discussed during a meeting focusing in part on estate planning. We do not find testimony to that effect to be credible, and that lack of credibility infects all of the testimony petitioner offered about what Clyde Sr. allegedly said or intended about the purpose of the family limited partnership.

Estate of Turner v. Com’r In our finding we rely partially on Mr. Coyle’s letter to Clyde Sr. in which he wrote: “A key element to a gifting plan is the need of a sound appraisal of the partnership for tax purposes. ” And indeed such appraisal was the key to Clyde Sr. ’s estate plan: both the gift tax and estate tax returns used substantial discounts despite the fact that the partnership assets at each relevant date consisted of, inter alia, cash equivalents, and marketable securities. In summary, we conclude that the formation of Turner & Co. had testamentary characteristics and Clyde Sr. did not curtail his enjoyment of the transferred assets after formation of the partnership.

Estate of Turner v. Com’r As a general partner, Clyde Sr. had the sole and absolute discretion to make pro rata distributions of partnership income (in addition to distributions to pay Federal and State tax liabilities) and to make distributions in kind. Moreover, Clyde Sr. had the authority to amend the partnership agreement at any time without the consent of the limited partners. Finally, even after the gifts of limited partnership interests to their children and grandchildren, Clyde Sr. and Jewell owned more than 50 percent of the limited partnership interests in Turner & Co. and could make any decision requiring a majority vote of the limited partners.

Sophisticated Technique Valuation of LLC Interest – Formula Clause Estate of Petter v. Com’r, ___ F. 3 d ___ (9 th Cir. 8 -411)

Estate of Petter v. Com’r Anne Y. Petter (“Taxpayer” or “Anne”) transferred membership units in a family-owned LLC partly as a gift and partly by sale to two trusts and coupled the transfers with simultaneous gifts of LLC units to two charitable foundations. The transfer documents include both a dollar formula clause —which assigns to the trusts a number of LLC units worth a specified dollar amount and assigns the remainder of the units to the foundations—and a reallocation clause— which obligates the trusts to transfer additional units to the foundations if the value of the units the trusts initially receive is finally determined for federal gift tax purposes to exceed the specified dollar amount.

Estate of Petter v. Com’r Based on an initial appraisal of the LLC units, each foundation received a particular number of units. But after an Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) audit determined that the units had been undervalued, the foundations discovered they would receive additional units. Everyone agrees that the Taxpayer is entitled to a charitable deduction equal to the value of the units the foundations initially received. But is the Taxpayer also entitled to a charitable deduction equal to the value of the additional units the foundations will receive? The Tax Court answered that she was. We agree.

QPRT Case QPRT is a qualified personal residence trust Estate of Riese v. Com’r, T. C. Memo. 2011 -60 (3 -1511) Taxpayer won despite making some mistakes

Polling Question Regarding ways to save estate taxes: a. There are none b. There are thousands of ways but every one requires an expensive lawyer c. It often pays to consult with competent tax counsel d. A taxpayer can try but the IRS will always challenge them

Any Questions? Email Dennis at dgerschick@aol. com Call 770 -792 -7444 See www. Regal. Seminars. com

c91dfa26adf95a525f3fe6d14119f8d0.ppt