f629f287936a6cd39231e6621f5b92da.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 99

2002 Software Model Checking Willem Visser Research Institute for Advanced Computer Science NASA Ames Research Center wvisser@email. arc. nasa. gov 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002

2002 Software Model Checking Willem Visser Research Institute for Advanced Computer Science NASA Ames Research Center wvisser@email. arc. nasa. gov 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002

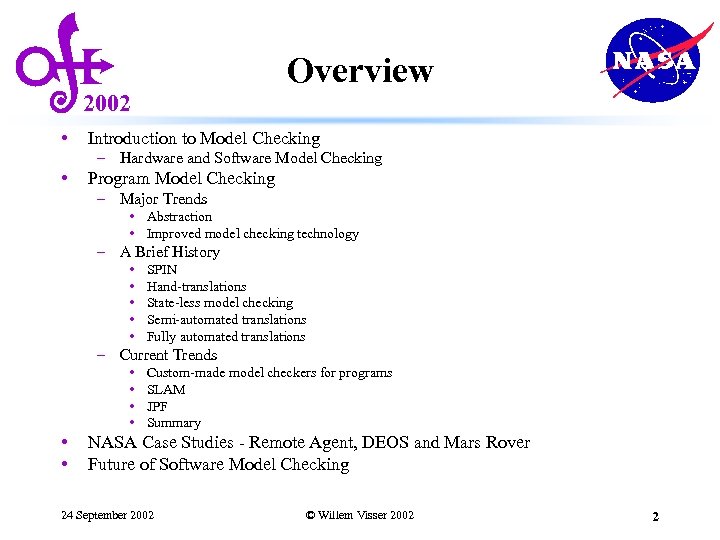

Overview 2002 • Introduction to Model Checking – Hardware and Software Model Checking • Program Model Checking – Major Trends • Abstraction • Improved model checking technology – A Brief History • • • SPIN Hand-translations State-less model checking Semi-automated translations Fully automated translations – Current Trends • • • Custom-made model checkers for programs SLAM JPF Summary NASA Case Studies - Remote Agent, DEOS and Mars Rover Future of Software Model Checking 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 2

Overview 2002 • Introduction to Model Checking – Hardware and Software Model Checking • Program Model Checking – Major Trends • Abstraction • Improved model checking technology – A Brief History • • • SPIN Hand-translations State-less model checking Semi-automated translations Fully automated translations – Current Trends • • • Custom-made model checkers for programs SLAM JPF Summary NASA Case Studies - Remote Agent, DEOS and Mars Rover Future of Software Model Checking 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 2

2002 Model Checking The Intuition • Calculate whether a system satisfies a certain behavioral property: – Is the system deadlock free? – Whenever a packet is sent will it eventually be received? • So it is like testing? No, major difference: – Look at all possible behaviors of a system • Automatic, if the system is finite-state – Potential for being a push-button technology – Almost no expert knowledge required • How do we describe the system? • How do we express the properties? 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 3

2002 Model Checking The Intuition • Calculate whether a system satisfies a certain behavioral property: – Is the system deadlock free? – Whenever a packet is sent will it eventually be received? • So it is like testing? No, major difference: – Look at all possible behaviors of a system • Automatic, if the system is finite-state – Potential for being a push-button technology – Almost no expert knowledge required • How do we describe the system? • How do we express the properties? 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 3

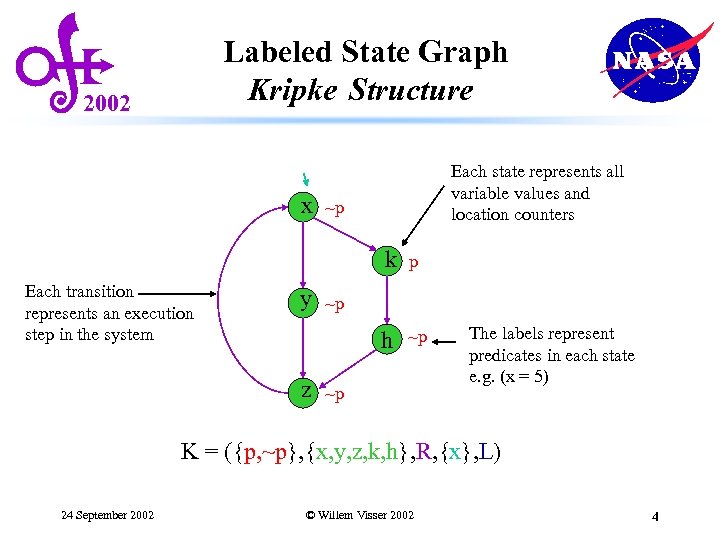

Labeled State Graph Kripke Structure 2002 x Each state represents all variable values and location counters ~p k Each transition represents an execution step in the system h h y z p ~p ~p ~p The labels represent predicates in each state e. g. (x = 5) K = ({p, ~p}, {x, y, z, k, h}, R, {x}, L) 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 4

Labeled State Graph Kripke Structure 2002 x Each state represents all variable values and location counters ~p k Each transition represents an execution step in the system h h y z p ~p ~p ~p The labels represent predicates in each state e. g. (x = 5) K = ({p, ~p}, {x, y, z, k, h}, R, {x}, L) 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 4

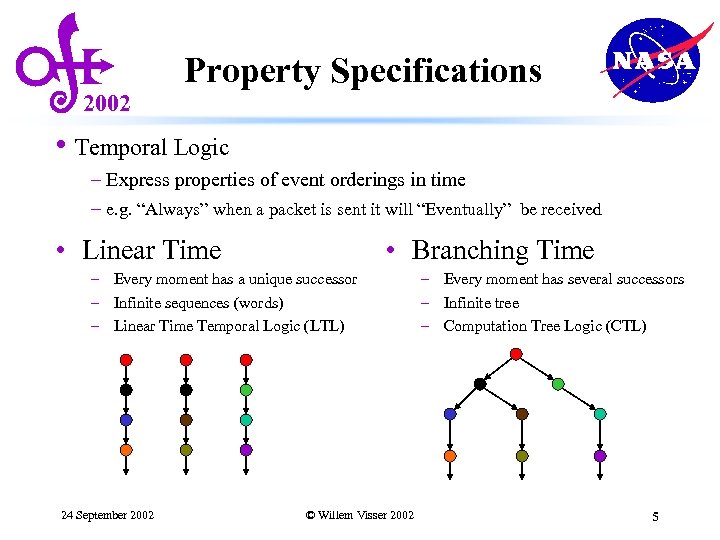

2002 Property Specifications • Temporal Logic – Express properties of event orderings in time – e. g. “Always” when a packet is sent it will “Eventually” be received • Linear Time • Branching Time – Every moment has a unique successor – Infinite sequences (words) – Linear Time Temporal Logic (LTL) 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 – Every moment has several successors – Infinite tree – Computation Tree Logic (CTL) 5

2002 Property Specifications • Temporal Logic – Express properties of event orderings in time – e. g. “Always” when a packet is sent it will “Eventually” be received • Linear Time • Branching Time – Every moment has a unique successor – Infinite sequences (words) – Linear Time Temporal Logic (LTL) 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 – Every moment has several successors – Infinite tree – Computation Tree Logic (CTL) 5

2002 Safety and Liveness • Safety properties – Invariants, deadlocks, reachability, etc. – Can be checked on finite traces – “something bad never happens” • Liveness Properties – Fairness, response, etc. – Infinite traces – “something good will eventually happen” 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 6

2002 Safety and Liveness • Safety properties – Invariants, deadlocks, reachability, etc. – Can be checked on finite traces – “something bad never happens” • Liveness Properties – Fairness, response, etc. – Infinite traces – “something good will eventually happen” 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 6

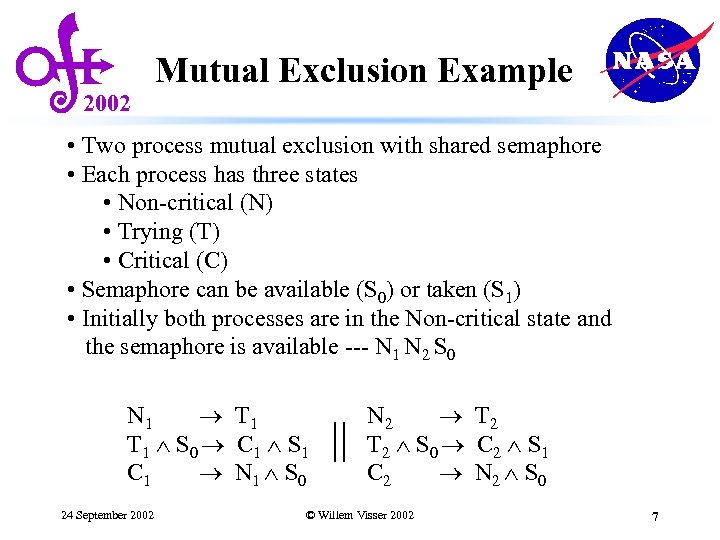

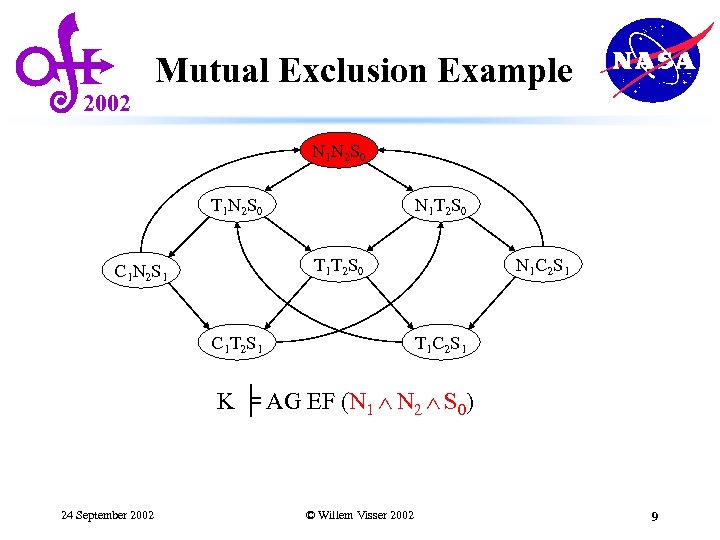

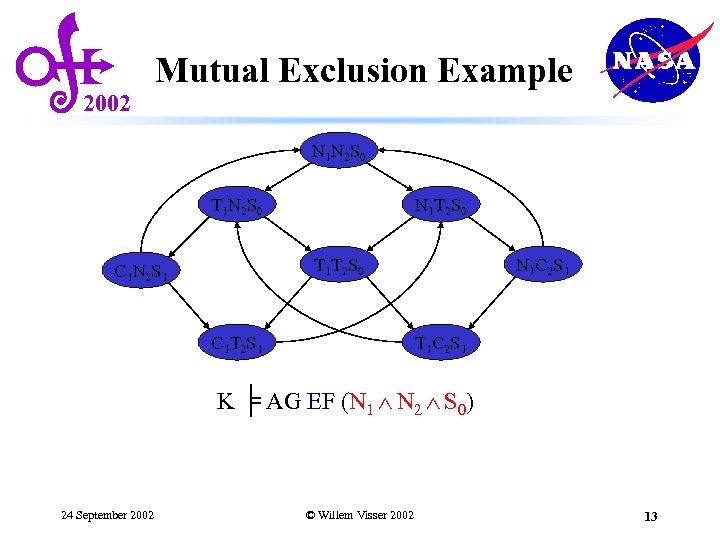

2002 Mutual Exclusion Example • Two process mutual exclusion with shared semaphore • Each process has three states • Non-critical (N) • Trying (T) • Critical (C) • Semaphore can be available (S 0) or taken (S 1) • Initially both processes are in the Non-critical state and the semaphore is available --- N 1 N 2 S 0 N 1 T 1 S 0 C 1 S 1 C 1 N 1 S 0 24 September 2002 || N 2 T 2 S 0 C 2 S 1 C 2 N 2 S 0 © Willem Visser 2002 7

2002 Mutual Exclusion Example • Two process mutual exclusion with shared semaphore • Each process has three states • Non-critical (N) • Trying (T) • Critical (C) • Semaphore can be available (S 0) or taken (S 1) • Initially both processes are in the Non-critical state and the semaphore is available --- N 1 N 2 S 0 N 1 T 1 S 0 C 1 S 1 C 1 N 1 S 0 24 September 2002 || N 2 T 2 S 0 C 2 S 1 C 2 N 2 S 0 © Willem Visser 2002 7

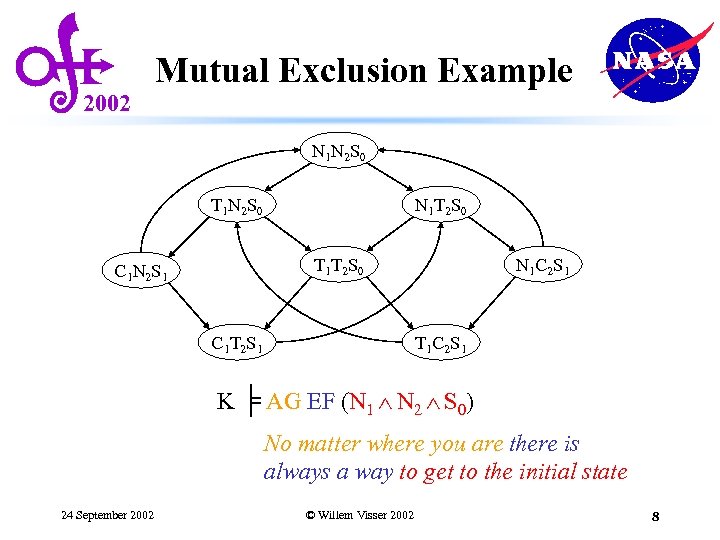

2002 Mutual Exclusion Example N 1 N 2 S 0 T 1 N 2 S 0 N 1 T 2 S 0 T 1 T 2 S 0 C 1 N 2 S 1 C 1 T 2 S 1 N 1 C 2 S 1 T 1 C 2 S 1 K ╞ AG EF (N 1 N 2 S 0) No matter where you are there is always a way to get to the initial state 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 8

2002 Mutual Exclusion Example N 1 N 2 S 0 T 1 N 2 S 0 N 1 T 2 S 0 T 1 T 2 S 0 C 1 N 2 S 1 C 1 T 2 S 1 N 1 C 2 S 1 T 1 C 2 S 1 K ╞ AG EF (N 1 N 2 S 0) No matter where you are there is always a way to get to the initial state 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 8

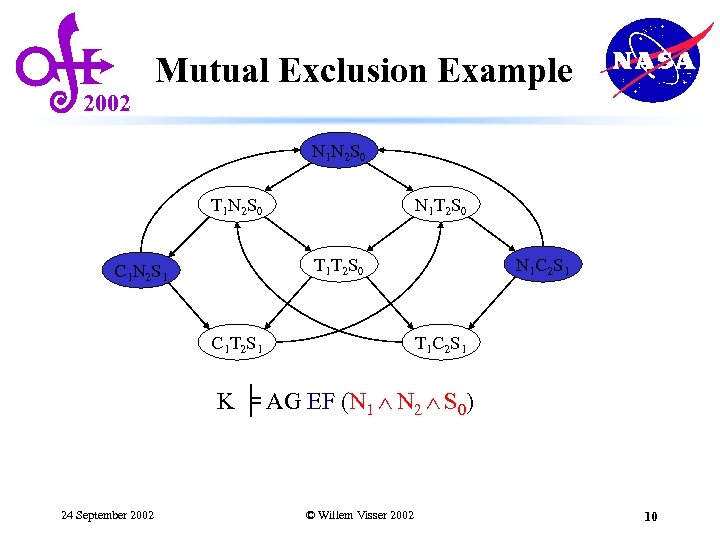

2002 Mutual Exclusion Example N 1 N 2 S 0 T 1 N 2 S 0 N 1 T 2 S 0 T 1 T 2 S 0 C 1 N 2 S 1 C 1 T 2 S 1 N 1 C 2 S 1 T 1 C 2 S 1 K ╞ AG EF (N 1 N 2 S 0) 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 9

2002 Mutual Exclusion Example N 1 N 2 S 0 T 1 N 2 S 0 N 1 T 2 S 0 T 1 T 2 S 0 C 1 N 2 S 1 C 1 T 2 S 1 N 1 C 2 S 1 T 1 C 2 S 1 K ╞ AG EF (N 1 N 2 S 0) 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 9

2002 Mutual Exclusion Example N 1 N 2 S 0 T 1 N 2 S 0 N 1 T 2 S 0 T 1 T 2 S 0 C 1 N 2 S 1 C 1 T 2 S 1 N 1 C 2 S 1 T 1 C 2 S 1 K ╞ AG EF (N 1 N 2 S 0) 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 10

2002 Mutual Exclusion Example N 1 N 2 S 0 T 1 N 2 S 0 N 1 T 2 S 0 T 1 T 2 S 0 C 1 N 2 S 1 C 1 T 2 S 1 N 1 C 2 S 1 T 1 C 2 S 1 K ╞ AG EF (N 1 N 2 S 0) 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 10

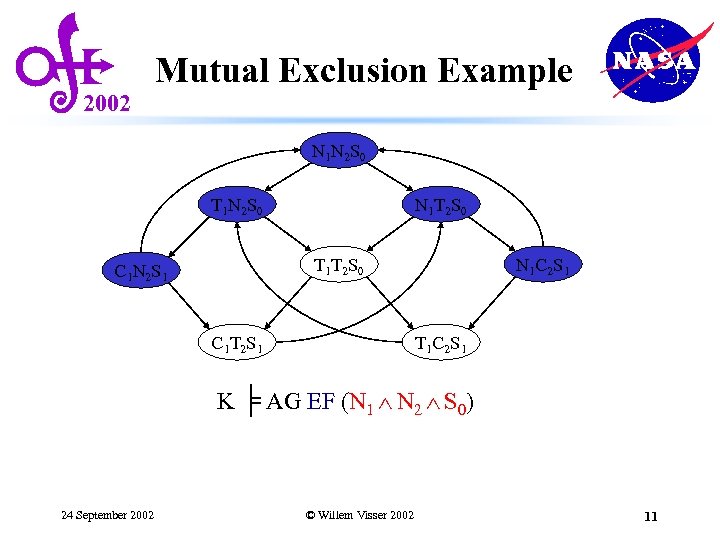

2002 Mutual Exclusion Example N 1 N 2 S 0 T 1 N 2 S 0 N 1 T 2 S 0 T 1 T 2 S 0 C 1 N 2 S 1 C 1 T 2 S 1 N 1 C 2 S 1 T 1 C 2 S 1 K ╞ AG EF (N 1 N 2 S 0) 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 11

2002 Mutual Exclusion Example N 1 N 2 S 0 T 1 N 2 S 0 N 1 T 2 S 0 T 1 T 2 S 0 C 1 N 2 S 1 C 1 T 2 S 1 N 1 C 2 S 1 T 1 C 2 S 1 K ╞ AG EF (N 1 N 2 S 0) 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 11

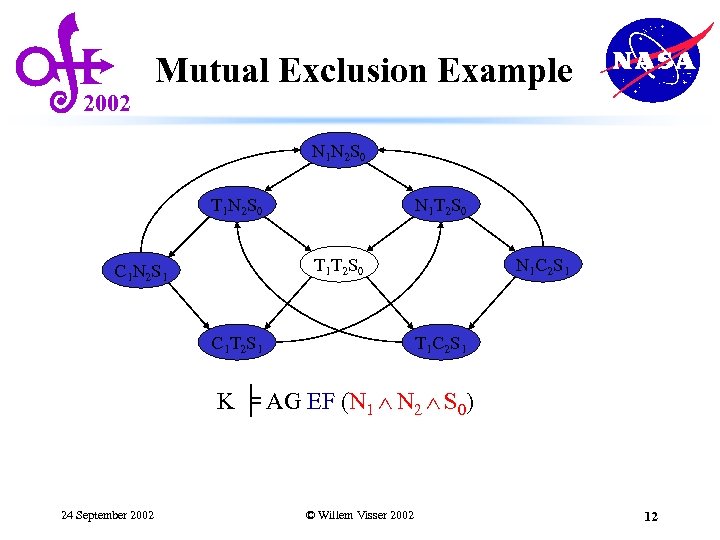

2002 Mutual Exclusion Example N 1 N 2 S 0 T 1 N 2 S 0 N 1 T 2 S 0 T 1 T 2 S 0 C 1 N 2 S 1 C 1 T 2 S 1 N 1 C 2 S 1 T 1 C 2 S 1 K ╞ AG EF (N 1 N 2 S 0) 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 12

2002 Mutual Exclusion Example N 1 N 2 S 0 T 1 N 2 S 0 N 1 T 2 S 0 T 1 T 2 S 0 C 1 N 2 S 1 C 1 T 2 S 1 N 1 C 2 S 1 T 1 C 2 S 1 K ╞ AG EF (N 1 N 2 S 0) 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 12

2002 Mutual Exclusion Example N 1 N 2 S 0 T 1 N 2 S 0 N 1 T 2 S 0 T 1 T 2 S 0 C 1 N 2 S 1 C 1 T 2 S 1 N 1 C 2 S 1 T 1 C 2 S 1 K ╞ AG EF (N 1 N 2 S 0) 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 13

2002 Mutual Exclusion Example N 1 N 2 S 0 T 1 N 2 S 0 N 1 T 2 S 0 T 1 T 2 S 0 C 1 N 2 S 1 C 1 T 2 S 1 N 1 C 2 S 1 T 1 C 2 S 1 K ╞ AG EF (N 1 N 2 S 0) 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 13

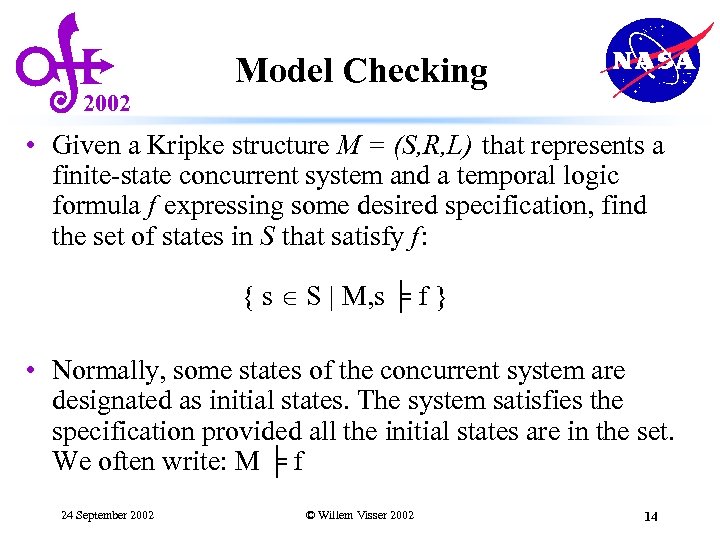

2002 Model Checking • Given a Kripke structure M = (S, R, L) that represents a finite-state concurrent system and a temporal logic formula f expressing some desired specification, find the set of states in S that satisfy f: { s S | M, s ╞ f } • Normally, some states of the concurrent system are designated as initial states. The system satisfies the specification provided all the initial states are in the set. We often write: M ╞ f 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 14

2002 Model Checking • Given a Kripke structure M = (S, R, L) that represents a finite-state concurrent system and a temporal logic formula f expressing some desired specification, find the set of states in S that satisfy f: { s S | M, s ╞ f } • Normally, some states of the concurrent system are designated as initial states. The system satisfies the specification provided all the initial states are in the set. We often write: M ╞ f 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 14

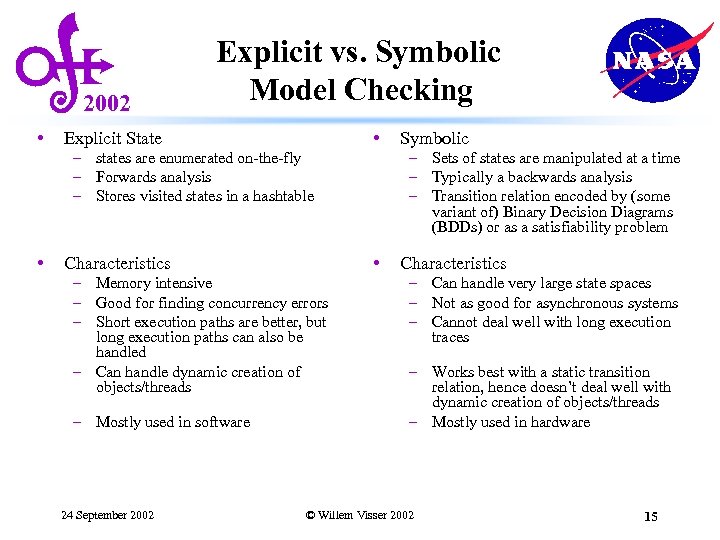

2002 • Explicit vs. Symbolic Model Checking • Explicit State – states are enumerated on-the-fly – Forwards analysis – Stores visited states in a hashtable • – Memory intensive – Good for finding concurrency errors – Short execution paths are better, but long execution paths can also be handled – Can handle dynamic creation of objects/threads – Mostly used in software 24 September 2002 – Sets of states are manipulated at a time – Typically a backwards analysis – Transition relation encoded by (some variant of) Binary Decision Diagrams (BDDs) or as a satisfiability problem • Characteristics Symbolic Characteristics – Can handle very large state spaces – Not as good for asynchronous systems – Cannot deal well with long execution traces – Works best with a static transition relation, hence doesn’t deal well with dynamic creation of objects/threads – Mostly used in hardware © Willem Visser 2002 15

2002 • Explicit vs. Symbolic Model Checking • Explicit State – states are enumerated on-the-fly – Forwards analysis – Stores visited states in a hashtable • – Memory intensive – Good for finding concurrency errors – Short execution paths are better, but long execution paths can also be handled – Can handle dynamic creation of objects/threads – Mostly used in software 24 September 2002 – Sets of states are manipulated at a time – Typically a backwards analysis – Transition relation encoded by (some variant of) Binary Decision Diagrams (BDDs) or as a satisfiability problem • Characteristics Symbolic Characteristics – Can handle very large state spaces – Not as good for asynchronous systems – Cannot deal well with long execution traces – Works best with a static transition relation, hence doesn’t deal well with dynamic creation of objects/threads – Mostly used in hardware © Willem Visser 2002 15

2002 Overview • Introduction to Model Checking – Hardware Model Checking – Software Model Checking • Program Model Checking • Case Studies • Future of Software Model Checking 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 16

2002 Overview • Introduction to Model Checking – Hardware Model Checking – Software Model Checking • Program Model Checking • Case Studies • Future of Software Model Checking 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 16

2002 Hardware Model Checking • BDD-based model checking was the enabling technology – Hardware is typically synchronous and regular, hence the transition relation can be encoded efficiently – Execution paths are typically very short • The Intel Pentium bug, was the “disaster” that got model checking on the map in the hardware industry – What is it going to take in the software world? • Intel, IBM, Motorola, etc. now employ hundreds of model checking experts 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 17

2002 Hardware Model Checking • BDD-based model checking was the enabling technology – Hardware is typically synchronous and regular, hence the transition relation can be encoded efficiently – Execution paths are typically very short • The Intel Pentium bug, was the “disaster” that got model checking on the map in the hardware industry – What is it going to take in the software world? • Intel, IBM, Motorola, etc. now employ hundreds of model checking experts 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 17

2002 Software Model Checking • Although the early papers on model checking focused on software, not much happened until 1997 • Until 1997 most work was on software designs – Since catching bugs early is more cost-effective – Problem is that everybody use a different design notation, and although bugs were found the field never really moved beyond some compelling case-studies – Reality is that people write code first, rather than design • The field took off when the seemingly harder problem of analyzing actual source code was first attempted 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 18

2002 Software Model Checking • Although the early papers on model checking focused on software, not much happened until 1997 • Until 1997 most work was on software designs – Since catching bugs early is more cost-effective – Problem is that everybody use a different design notation, and although bugs were found the field never really moved beyond some compelling case-studies – Reality is that people write code first, rather than design • The field took off when the seemingly harder problem of analyzing actual source code was first attempted 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 18

2002 Program Model Checking • Why is program analysis with a model checker so much more interesting? – Designs are hard to come by, but buggy programs are everywhere! – Testing is inadequate for complex software (concurrency, pointers, objects, etc. ) – Static program analysis was already an established field, mostly in compiler optimization, but also in verification. 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 19

2002 Program Model Checking • Why is program analysis with a model checker so much more interesting? – Designs are hard to come by, but buggy programs are everywhere! – Testing is inadequate for complex software (concurrency, pointers, objects, etc. ) – Static program analysis was already an established field, mostly in compiler optimization, but also in verification. 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 19

2002 The Trends in Program Model Checking Most model checkers cannot deal with the features of modern programming languages • Bringing programs to model checking – Abstraction (including translation) • Bringing model checking to programs – Improve model checking to directly deal with programs as input 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 20

2002 The Trends in Program Model Checking Most model checkers cannot deal with the features of modern programming languages • Bringing programs to model checking – Abstraction (including translation) • Bringing model checking to programs – Improve model checking to directly deal with programs as input 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 20

2002 Overview • Introduction to Model Checking • Program Model Checking – Major Trends • Abstraction • Improved model checking technology – A Brief History – Current Trends • Case Studies • Future of Software Model Checking 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 21

2002 Overview • Introduction to Model Checking • Program Model Checking – Major Trends • Abstraction • Improved model checking technology – A Brief History – Current Trends • Case Studies • Future of Software Model Checking 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 21

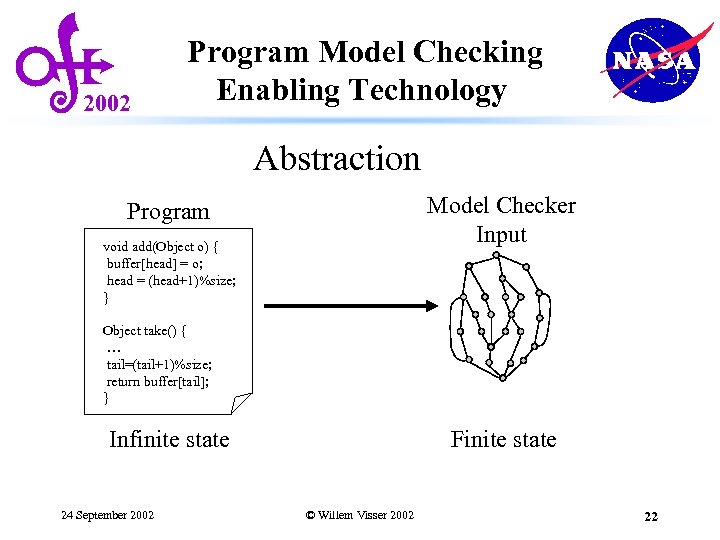

2002 Program Model Checking Enabling Technology Abstraction Model Checker Input Program void add(Object o) { buffer[head] = o; head = (head+1)%size; } Object take() { … tail=(tail+1)%size; return buffer[tail]; } Infinite state 24 September 2002 Finite state © Willem Visser 2002 22

2002 Program Model Checking Enabling Technology Abstraction Model Checker Input Program void add(Object o) { buffer[head] = o; head = (head+1)%size; } Object take() { … tail=(tail+1)%size; return buffer[tail]; } Infinite state 24 September 2002 Finite state © Willem Visser 2002 22

2002 Abstraction • Model checkers don’t take real “programs” as input • Model checkers typically work on finite state systems • Abstraction therefore solves two problems – It allows model checkers to analyze a notation they couldn’t deal with before, and, – Cuts the state space size to something manageable • Abstraction comes in three flavors – Over-approximations, i. e. more behaviors are added to the abstracted system than are present in the original – Under-approximations, i. e. less behaviors are present in the abstracted system than are present in the original – Precise abstractions, i. e. the same behaviors are present in the abstracted and original program 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 23

2002 Abstraction • Model checkers don’t take real “programs” as input • Model checkers typically work on finite state systems • Abstraction therefore solves two problems – It allows model checkers to analyze a notation they couldn’t deal with before, and, – Cuts the state space size to something manageable • Abstraction comes in three flavors – Over-approximations, i. e. more behaviors are added to the abstracted system than are present in the original – Under-approximations, i. e. less behaviors are present in the abstracted system than are present in the original – Precise abstractions, i. e. the same behaviors are present in the abstracted and original program 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 23

Under-Approximation 2002 “Meat-Axe” Abstraction • Remove parts of the program deemed “irrelevant” to the property being checked – Limit input values to 0. . 10 rather than all integer values – Queue size 3 instead of unbounded, etc. • The abstraction of choice in the early days of program model checking – used during the translation of code to a model checker’s input language • Typically manual, with no guarantee that the right behaviors are removed. • Precise abstraction, w. r. t. the property being checked, may be obtained if the behaviors being removed are indeed not influencing the property – Program slicing is an example of an automated under-approximation that will lead to a precise abstraction w. r. t. the property being checked 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 24

Under-Approximation 2002 “Meat-Axe” Abstraction • Remove parts of the program deemed “irrelevant” to the property being checked – Limit input values to 0. . 10 rather than all integer values – Queue size 3 instead of unbounded, etc. • The abstraction of choice in the early days of program model checking – used during the translation of code to a model checker’s input language • Typically manual, with no guarantee that the right behaviors are removed. • Precise abstraction, w. r. t. the property being checked, may be obtained if the behaviors being removed are indeed not influencing the property – Program slicing is an example of an automated under-approximation that will lead to a precise abstraction w. r. t. the property being checked 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 24

Over-Approximations 2002 Abstract Interpretation • Maps sets of states in the concrete program to one state in the abstract program – Reduces the number of states, but increases the number of possible transitions, and hence the number of behaviors – Can in rare cases lead to a precise abstraction • Type-based abstractions – Replace int by Signs abstraction {neg, pos, zero} • Predicate abstraction – Replace predicates in the program by boolean variables, and replace each instruction that modifies the predicate with a corresponding instruction that modifies the boolean. • Automated (conservative) abstraction • Eliminating spurious errors is the big problem – Abstract program has more behaviors, therefore when an error is found in the abstract program, is that also an error in the original program? – Most research focuses on this problem, and its counter-part the elimination of spurious errors, often called abstraction refinement 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 25

Over-Approximations 2002 Abstract Interpretation • Maps sets of states in the concrete program to one state in the abstract program – Reduces the number of states, but increases the number of possible transitions, and hence the number of behaviors – Can in rare cases lead to a precise abstraction • Type-based abstractions – Replace int by Signs abstraction {neg, pos, zero} • Predicate abstraction – Replace predicates in the program by boolean variables, and replace each instruction that modifies the predicate with a corresponding instruction that modifies the boolean. • Automated (conservative) abstraction • Eliminating spurious errors is the big problem – Abstract program has more behaviors, therefore when an error is found in the abstract program, is that also an error in the original program? – Most research focuses on this problem, and its counter-part the elimination of spurious errors, often called abstraction refinement 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 25

2002 Bringing Model Checking to Programs • Allow model checkers to take modern programming languages as input, or, notations that are of similar expressive power • Major hurdle is how to encode the state of the system efficiently • Alternatively state-less model checking – No state encoding or storing • Almost exclusively explicit-state model checking • Abstraction can still be used as well – Source to source abstractions 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 26

2002 Bringing Model Checking to Programs • Allow model checkers to take modern programming languages as input, or, notations that are of similar expressive power • Major hurdle is how to encode the state of the system efficiently • Alternatively state-less model checking – No state encoding or storing • Almost exclusively explicit-state model checking • Abstraction can still be used as well – Source to source abstractions 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 26

Overview 2002 • Introduction to Model Checking • Program Model Checking – Major Trends – A Brief History • SPIN • Hand-translations • State-less model checking – Partial-order reductions – Veri. Soft • Semi-automated translations • Fully automated translations – Current Trends • Case Studies • Future of Software Model Checking 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 27

Overview 2002 • Introduction to Model Checking • Program Model Checking – Major Trends – A Brief History • SPIN • Hand-translations • State-less model checking – Partial-order reductions – Veri. Soft • Semi-automated translations • Fully automated translations – Current Trends • Case Studies • Future of Software Model Checking 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 27

2002 The Early Years • Hand-translation with ad-hoc abstractions – 1980 through mid 1990 s • Semi-automated, table-driven translations – 1998 • Automated translations still with ad-hoc abstractions – 1997 -1999 • State-less model checking for C – Veri. Soft 1997 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 28

2002 The Early Years • Hand-translation with ad-hoc abstractions – 1980 through mid 1990 s • Semi-automated, table-driven translations – 1998 • Automated translations still with ad-hoc abstractions – 1997 -1999 • State-less model checking for C – Veri. Soft 1997 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 28

Overview 2002 • Introduction to Model Checking • Program Model Checking – Major Trends – A Brief History • SPIN • Hand-translations • State-less model checking – Partial-order reductions – Veri. Soft • Semi-automated translations • Fully automated translations – Current Trends • Case Studies • Future of Software Model Checking 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 29

Overview 2002 • Introduction to Model Checking • Program Model Checking – Major Trends – A Brief History • SPIN • Hand-translations • State-less model checking – Partial-order reductions – Veri. Soft • Semi-automated translations • Fully automated translations – Current Trends • Case Studies • Future of Software Model Checking 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 29

2002 SPIN Model Checker • Kripke structures are described as “programs” in the PROMELA language – Kripke structure is generated on-the-fly during model checking • Automata based model checker – Translates LTL formula to Büchi automaton • By far the most popular model checker – 10 th SPIN Workshop to be held with ICSE – May 2003 • Relevant theoretical papers can be found here – http: //netlib. bell-labs. com/netlib/spin/whatispin. html • Ideal for software model checking due to expressiveness of the PROMELA language – Close to a real programming language • Gerard Holzmann won the ACM software award for SPIN 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 30

2002 SPIN Model Checker • Kripke structures are described as “programs” in the PROMELA language – Kripke structure is generated on-the-fly during model checking • Automata based model checker – Translates LTL formula to Büchi automaton • By far the most popular model checker – 10 th SPIN Workshop to be held with ICSE – May 2003 • Relevant theoretical papers can be found here – http: //netlib. bell-labs. com/netlib/spin/whatispin. html • Ideal for software model checking due to expressiveness of the PROMELA language – Close to a real programming language • Gerard Holzmann won the ACM software award for SPIN 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 30

2002 Hand-Translation abstraction Verification model translation Program • Hand translation of program to model checker’s input notation • “Meat-axe” approach to abstraction • Labor intensive and error-prone 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 31

2002 Hand-Translation abstraction Verification model translation Program • Hand translation of program to model checker’s input notation • “Meat-axe” approach to abstraction • Labor intensive and error-prone 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 31

2002 Hand-Translation Examples • Remote Agent – Havelund, Penix, Lowry 1997 – – http: //ase. arc. nasa. gov/havelund Translation from Lisp to Promela (most effort) Heavy abstraction 3 man months • DEOS – Penix, Visser, et al. 1998/1999 – – http: //ase. arc. nasa. gov/visser C++ to Promela (most effort in environment generation) Limited abstraction - programmers produced sliced system 3 man months 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 32

2002 Hand-Translation Examples • Remote Agent – Havelund, Penix, Lowry 1997 – – http: //ase. arc. nasa. gov/havelund Translation from Lisp to Promela (most effort) Heavy abstraction 3 man months • DEOS – Penix, Visser, et al. 1998/1999 – – http: //ase. arc. nasa. gov/visser C++ to Promela (most effort in environment generation) Limited abstraction - programmers produced sliced system 3 man months 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 32

Overview 2002 • Introduction to Model Checking • Program Model Checking – Major Trends – A Brief History • SPIN • Hand-translations • State-less model checking – Partial-order reductions – Veri. Soft • Semi-automated translations • Fully automated translations – Current Trends • Case Studies • Future of Software Model Checking 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 33

Overview 2002 • Introduction to Model Checking • Program Model Checking – Major Trends – A Brief History • SPIN • Hand-translations • State-less model checking – Partial-order reductions – Veri. Soft • Semi-automated translations • Fully automated translations – Current Trends • Case Studies • Future of Software Model Checking 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 33

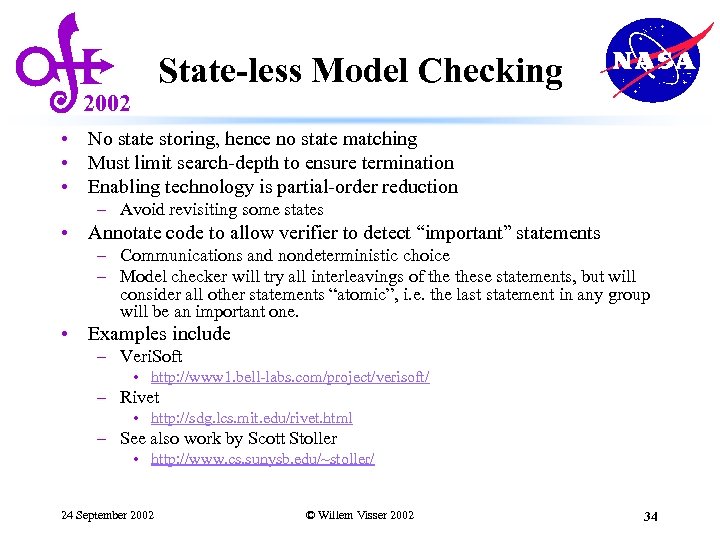

State-less Model Checking 2002 • No state storing, hence no state matching • Must limit search-depth to ensure termination • Enabling technology is partial-order reduction – Avoid revisiting some states • Annotate code to allow verifier to detect “important” statements – Communications and nondeterministic choice – Model checker will try all interleavings of these statements, but will consider all other statements “atomic”, i. e. the last statement in any group will be an important one. • Examples include – Veri. Soft • http: //www 1. bell-labs. com/project/verisoft/ – Rivet • http: //sdg. lcs. mit. edu/rivet. html – See also work by Scott Stoller • http: //www. cs. sunysb. edu/~stoller/ 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 34

State-less Model Checking 2002 • No state storing, hence no state matching • Must limit search-depth to ensure termination • Enabling technology is partial-order reduction – Avoid revisiting some states • Annotate code to allow verifier to detect “important” statements – Communications and nondeterministic choice – Model checker will try all interleavings of these statements, but will consider all other statements “atomic”, i. e. the last statement in any group will be an important one. • Examples include – Veri. Soft • http: //www 1. bell-labs. com/project/verisoft/ – Rivet • http: //sdg. lcs. mit. edu/rivet. html – See also work by Scott Stoller • http: //www. cs. sunysb. edu/~stoller/ 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 34

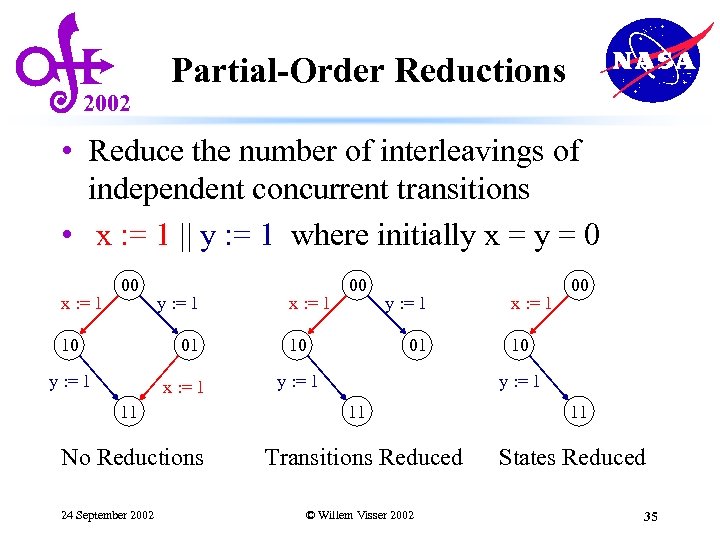

2002 Partial-Order Reductions • Reduce the number of interleavings of independent concurrent transitions • x : = 1 || y : = 1 where initially x = y = 0 x : = 1 00 10 y : = 1 01 y : = 1 x : = 1 11 No Reductions 24 September 2002 x : = 1 00 10 y : = 1 01 y : = 1 x : = 1 00 10 y : = 1 11 Transitions Reduced © Willem Visser 2002 11 States Reduced 35

2002 Partial-Order Reductions • Reduce the number of interleavings of independent concurrent transitions • x : = 1 || y : = 1 where initially x = y = 0 x : = 1 00 10 y : = 1 01 y : = 1 x : = 1 11 No Reductions 24 September 2002 x : = 1 00 10 y : = 1 01 y : = 1 x : = 1 00 10 y : = 1 11 Transitions Reduced © Willem Visser 2002 11 States Reduced 35

Partial Order Reductions 2002 Basic Ideas • Independence – Independent transitions cannot disable nor enable each other – Enabled independent transitions are commutative • Partial-order reductions only apply during the on-the-fly construction of the Kripke structure • Based on a selective search principle – Compute a subset of enabled transitions in a state to execute • Sleep sets (Reduce transitions) • Persistent sets (Reduce states) 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 36

Partial Order Reductions 2002 Basic Ideas • Independence – Independent transitions cannot disable nor enable each other – Enabled independent transitions are commutative • Partial-order reductions only apply during the on-the-fly construction of the Kripke structure • Based on a selective search principle – Compute a subset of enabled transitions in a state to execute • Sleep sets (Reduce transitions) • Persistent sets (Reduce states) 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 36

2002 Persistent Set Reductions • A subset of the enabled transitions is called persistent, when any transition can be executed from outside the set and it will not interact or affect the transitions inside the set – Use the static structure of the system to determine what goes into the persistent set – Note, all enabled transitions are trivially persistent • Only execute transitions in the persistent set • Persistent set algorithm is used within SPIN • See papers by Godefroid and Peled 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 37

2002 Persistent Set Reductions • A subset of the enabled transitions is called persistent, when any transition can be executed from outside the set and it will not interact or affect the transitions inside the set – Use the static structure of the system to determine what goes into the persistent set – Note, all enabled transitions are trivially persistent • Only execute transitions in the persistent set • Persistent set algorithm is used within SPIN • See papers by Godefroid and Peled 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 37

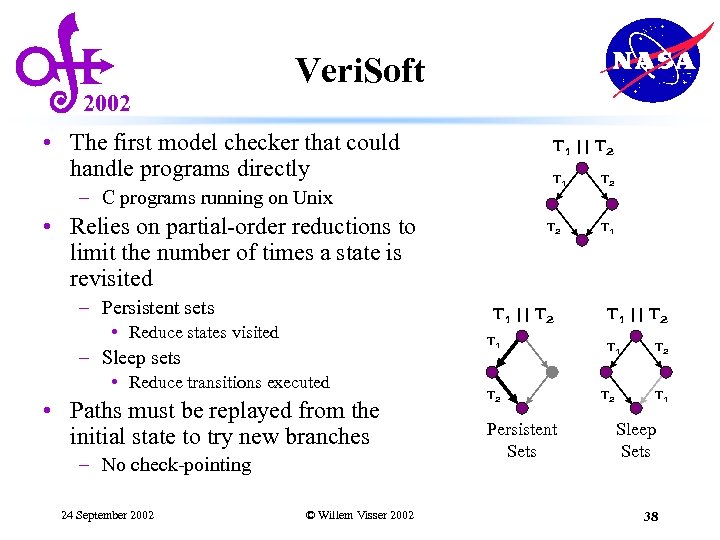

2002 Veri. Soft • The first model checker that could handle programs directly T 1 || T 2 T 1 – C programs running on Unix • Relies on partial-order reductions to limit the number of times a state is revisited – Persistent sets T 1 || T 2 • Reduce states visited T 1 – Sleep sets • Reduce transitions executed • Paths must be replayed from the initial state to try new branches – No check-pointing 24 September 2002 T 2 © Willem Visser 2002 T 2 Persistent Sets T 2 T 1 || T 2 T 1 Sleep Sets 38

2002 Veri. Soft • The first model checker that could handle programs directly T 1 || T 2 T 1 – C programs running on Unix • Relies on partial-order reductions to limit the number of times a state is revisited – Persistent sets T 1 || T 2 • Reduce states visited T 1 – Sleep sets • Reduce transitions executed • Paths must be replayed from the initial state to try new branches – No check-pointing 24 September 2002 T 2 © Willem Visser 2002 T 2 Persistent Sets T 2 T 1 || T 2 T 1 Sleep Sets 38

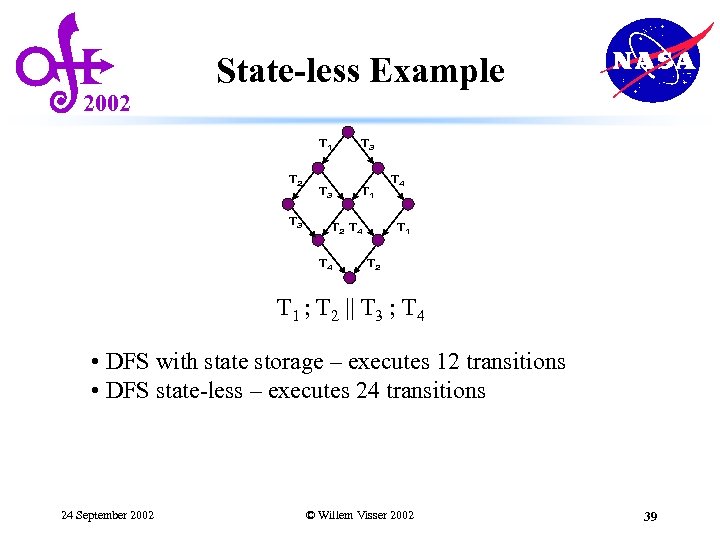

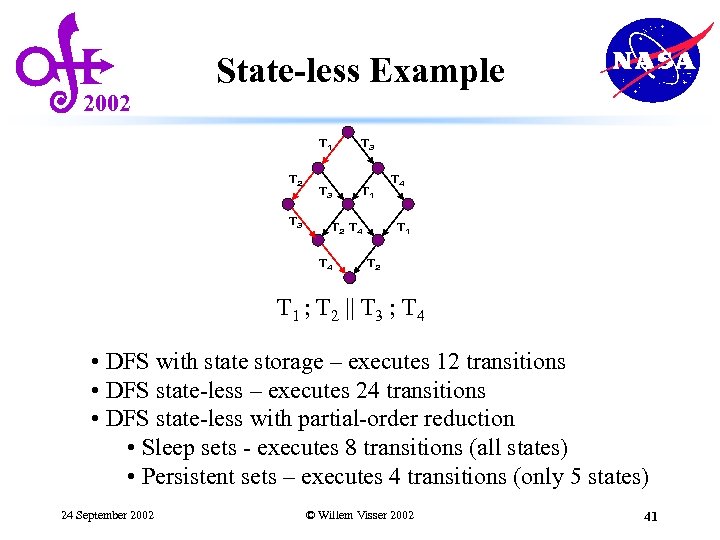

2002 State-less Example T 1 T 2 T 3 T 3 T 1 T 2 T 4 T 4 T 1 T 2 T 1 ; T 2 || T 3 ; T 4 • DFS with state storage – executes 12 transitions • DFS state-less – executes 24 transitions 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 39

2002 State-less Example T 1 T 2 T 3 T 3 T 1 T 2 T 4 T 4 T 1 T 2 T 1 ; T 2 || T 3 ; T 4 • DFS with state storage – executes 12 transitions • DFS state-less – executes 24 transitions 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 39

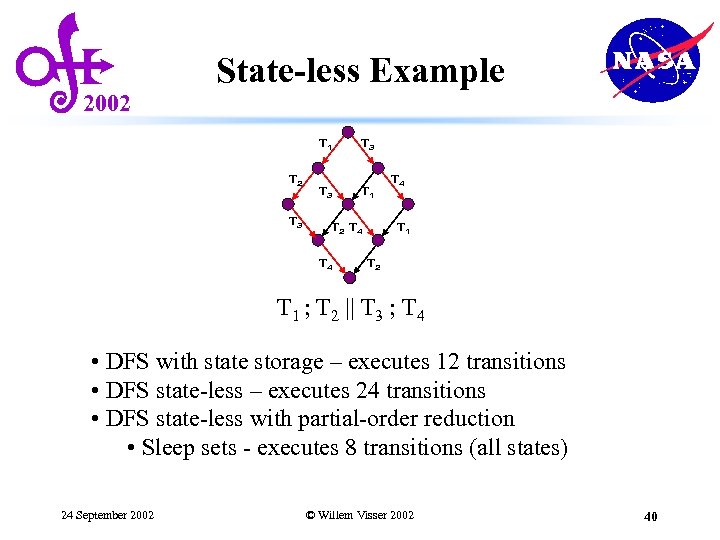

2002 State-less Example T 1 T 2 T 3 T 3 T 1 T 2 T 4 T 4 T 1 T 2 T 1 ; T 2 || T 3 ; T 4 • DFS with state storage – executes 12 transitions • DFS state-less – executes 24 transitions • DFS state-less with partial-order reduction • Sleep sets - executes 8 transitions (all states) 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 40

2002 State-less Example T 1 T 2 T 3 T 3 T 1 T 2 T 4 T 4 T 1 T 2 T 1 ; T 2 || T 3 ; T 4 • DFS with state storage – executes 12 transitions • DFS state-less – executes 24 transitions • DFS state-less with partial-order reduction • Sleep sets - executes 8 transitions (all states) 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 40

2002 State-less Example T 1 T 2 T 3 T 3 T 1 T 2 T 4 T 4 T 1 T 2 T 1 ; T 2 || T 3 ; T 4 • DFS with state storage – executes 12 transitions • DFS state-less – executes 24 transitions • DFS state-less with partial-order reduction • Sleep sets - executes 8 transitions (all states) • Persistent sets – executes 4 transitions (only 5 states) 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 41

2002 State-less Example T 1 T 2 T 3 T 3 T 1 T 2 T 4 T 4 T 1 T 2 T 1 ; T 2 || T 3 ; T 4 • DFS with state storage – executes 12 transitions • DFS state-less – executes 24 transitions • DFS state-less with partial-order reduction • Sleep sets - executes 8 transitions (all states) • Persistent sets – executes 4 transitions (only 5 states) 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 41

Overview 2002 • Introduction to Model Checking • Program Model Checking – Major Trends – A Brief History • SPIN • Hand-translations • State-less model checking – Partial-order reductions – Veri. Soft • Semi-automated translations • Fully automated translations – Current Trends • Case Studies • Future of Software Model Checking 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 42

Overview 2002 • Introduction to Model Checking • Program Model Checking – Major Trends – A Brief History • SPIN • Hand-translations • State-less model checking – Partial-order reductions – Veri. Soft • Semi-automated translations • Fully automated translations – Current Trends • Case Studies • Future of Software Model Checking 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 42

2002 Semi-Automatic Translation • Table-driven translation and abstraction – Feaver system by Gerard Holzmann – User specifies code fragments in C and how to translate them to Promela (SPIN) – Translation is then automatic – Found 75 errors in Lucent’s Path. Star system – http: //cm. bell-labs. com/cm/cs/who/gerard/ • Advantages – Can be reused when program changes – Works well for programs with long development and only local changes 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 43

2002 Semi-Automatic Translation • Table-driven translation and abstraction – Feaver system by Gerard Holzmann – User specifies code fragments in C and how to translate them to Promela (SPIN) – Translation is then automatic – Found 75 errors in Lucent’s Path. Star system – http: //cm. bell-labs. com/cm/cs/who/gerard/ • Advantages – Can be reused when program changes – Works well for programs with long development and only local changes 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 43

2002 Fully Automatic Translation • Advantage – No human intervention required • Disadvantage – Limited by capabilities of target system • Examples – Java Path. Finder 1 - http: //ase. arc. nasa. gov/havelund/jpf. html • Translates from Java to Promela (Spin) – JCAT - http: //www. dai-arc. polito. it/dai-arc/auto/tools/tool 6. shtml • Translates from Java to Promela (or d. Spin) – Bandera - http: //www. cis. ksu. edu/santos/bandera/ • Translates from Java bytecode to Promela, SMV or d. Spin 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 44

2002 Fully Automatic Translation • Advantage – No human intervention required • Disadvantage – Limited by capabilities of target system • Examples – Java Path. Finder 1 - http: //ase. arc. nasa. gov/havelund/jpf. html • Translates from Java to Promela (Spin) – JCAT - http: //www. dai-arc. polito. it/dai-arc/auto/tools/tool 6. shtml • Translates from Java to Promela (or d. Spin) – Bandera - http: //www. cis. ksu. edu/santos/bandera/ • Translates from Java bytecode to Promela, SMV or d. Spin 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 44

Overview 2002 • Introduction to Model Checking • Program Model Checking – Major Trends – A Brief History – Current Trends • • • Custom-made model checkers for programs Abstraction SLAM JPF Summary Examples of other software analyses • Case Studies • Future of Software Model Checking 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 45

Overview 2002 • Introduction to Model Checking • Program Model Checking – Major Trends – A Brief History – Current Trends • • • Custom-made model checkers for programs Abstraction SLAM JPF Summary Examples of other software analyses • Case Studies • Future of Software Model Checking 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 45

![Program Model Checking Current Trends 2002 Program void add(Object o) { buffer[head] = o; Program Model Checking Current Trends 2002 Program void add(Object o) { buffer[head] = o;](https://present5.com/presentation/f629f287936a6cd39231e6621f5b92da/image-46.jpg) Program Model Checking Current Trends 2002 Program void add(Object o) { buffer[head] = o; head = (head+1)%size; } Object take() { … tail=(tail+1)%size; return buffer[tail]; } Abstraction Abstract Program Abstraction Correct Custom Model Checker T 1 > T 2 T 3 > T 4 T 5 > T 6 … Error-trace Abstraction refinement • Custom-made model checkers for programming languages with automatic abstraction at the source code level • Automatic abstraction & translation based transformation to new “abstract” formalism for model checker • Abstraction refinement mostly automated 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 46

Program Model Checking Current Trends 2002 Program void add(Object o) { buffer[head] = o; head = (head+1)%size; } Object take() { … tail=(tail+1)%size; return buffer[tail]; } Abstraction Abstract Program Abstraction Correct Custom Model Checker T 1 > T 2 T 3 > T 4 T 5 > T 6 … Error-trace Abstraction refinement • Custom-made model checkers for programming languages with automatic abstraction at the source code level • Automatic abstraction & translation based transformation to new “abstract” formalism for model checker • Abstraction refinement mostly automated 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 46

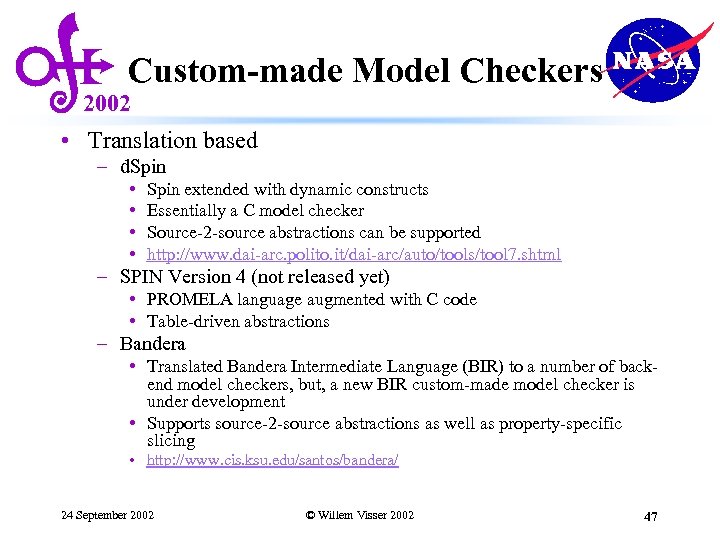

Custom-made Model Checkers 2002 • Translation based – d. Spin • • Spin extended with dynamic constructs Essentially a C model checker Source-2 -source abstractions can be supported http: //www. dai-arc. polito. it/dai-arc/auto/tools/tool 7. shtml – SPIN Version 4 (not released yet) • PROMELA language augmented with C code • Table-driven abstractions – Bandera • Translated Bandera Intermediate Language (BIR) to a number of backend model checkers, but, a new BIR custom-made model checker is under development • Supports source-2 -source abstractions as well as property-specific slicing • http: //www. cis. ksu. edu/santos/bandera/ 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 47

Custom-made Model Checkers 2002 • Translation based – d. Spin • • Spin extended with dynamic constructs Essentially a C model checker Source-2 -source abstractions can be supported http: //www. dai-arc. polito. it/dai-arc/auto/tools/tool 7. shtml – SPIN Version 4 (not released yet) • PROMELA language augmented with C code • Table-driven abstractions – Bandera • Translated Bandera Intermediate Language (BIR) to a number of backend model checkers, but, a new BIR custom-made model checker is under development • Supports source-2 -source abstractions as well as property-specific slicing • http: //www. cis. ksu. edu/santos/bandera/ 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 47

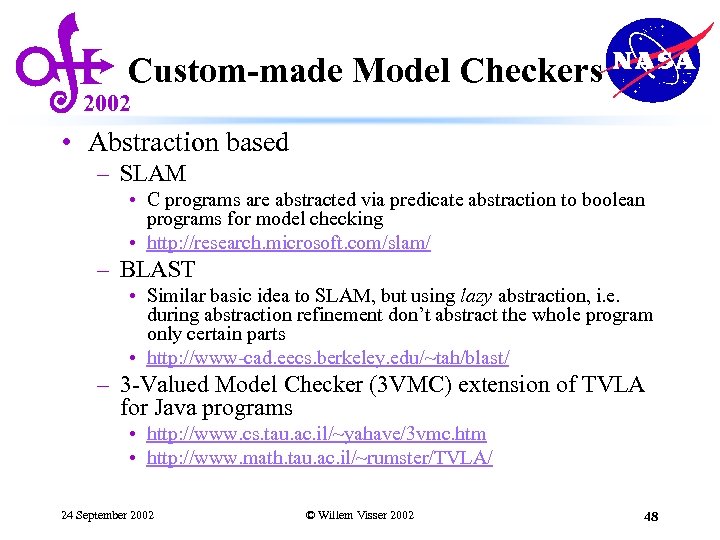

Custom-made Model Checkers 2002 • Abstraction based – SLAM • C programs are abstracted via predicate abstraction to boolean programs for model checking • http: //research. microsoft. com/slam/ – BLAST • Similar basic idea to SLAM, but using lazy abstraction, i. e. during abstraction refinement don’t abstract the whole program only certain parts • http: //www-cad. eecs. berkeley. edu/~tah/blast/ – 3 -Valued Model Checker (3 VMC) extension of TVLA for Java programs • http: //www. cs. tau. ac. il/~yahave/3 vmc. htm • http: //www. math. tau. ac. il/~rumster/TVLA/ 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 48

Custom-made Model Checkers 2002 • Abstraction based – SLAM • C programs are abstracted via predicate abstraction to boolean programs for model checking • http: //research. microsoft. com/slam/ – BLAST • Similar basic idea to SLAM, but using lazy abstraction, i. e. during abstraction refinement don’t abstract the whole program only certain parts • http: //www-cad. eecs. berkeley. edu/~tah/blast/ – 3 -Valued Model Checker (3 VMC) extension of TVLA for Java programs • http: //www. cs. tau. ac. il/~yahave/3 vmc. htm • http: //www. math. tau. ac. il/~rumster/TVLA/ 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 48

Overview 2002 • Introduction to Model Checking • Program Model Checking – Major Trends – A Brief History – Current Trends • • • Custom-made model checkers for programs Abstraction SLAM JPF Summary Examples of other software analyses • Case Studies • Future of Software Model Checking 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 49

Overview 2002 • Introduction to Model Checking • Program Model Checking – Major Trends – A Brief History – Current Trends • • • Custom-made model checkers for programs Abstraction SLAM JPF Summary Examples of other software analyses • Case Studies • Future of Software Model Checking 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 49

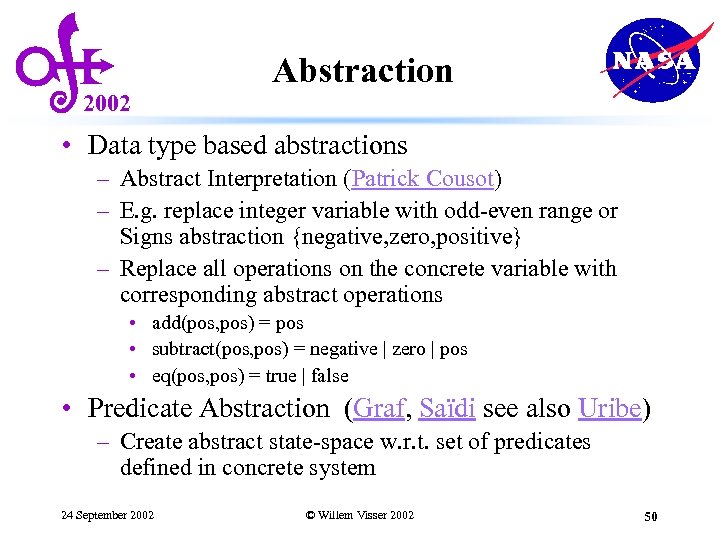

2002 Abstraction • Data type based abstractions – Abstract Interpretation (Patrick Cousot) – E. g. replace integer variable with odd-even range or Signs abstraction {negative, zero, positive} – Replace all operations on the concrete variable with corresponding abstract operations • add(pos, pos) = pos • subtract(pos, pos) = negative | zero | pos • eq(pos, pos) = true | false • Predicate Abstraction (Graf, Saïdi see also Uribe) – Create abstract state-space w. r. t. set of predicates defined in concrete system 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 50

2002 Abstraction • Data type based abstractions – Abstract Interpretation (Patrick Cousot) – E. g. replace integer variable with odd-even range or Signs abstraction {negative, zero, positive} – Replace all operations on the concrete variable with corresponding abstract operations • add(pos, pos) = pos • subtract(pos, pos) = negative | zero | pos • eq(pos, pos) = true | false • Predicate Abstraction (Graf, Saïdi see also Uribe) – Create abstract state-space w. r. t. set of predicates defined in concrete system 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 50

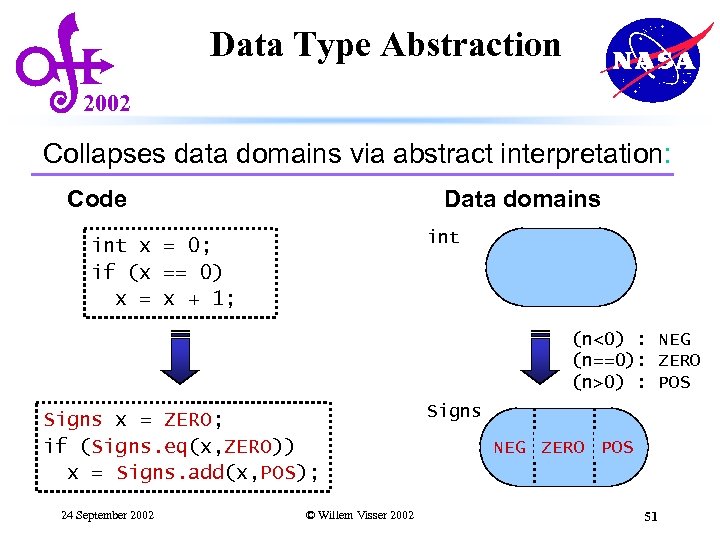

Data Type Abstraction 2002 Collapses data domains via abstract interpretation: Code Data domains int x = 0; if (x == 0) x = x + 1; (n<0) : NEG (n==0): ZERO (n>0) : POS Signs x = ZERO; if (Signs. eq(x, ZERO)) x = Signs. add(x, POS); 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 Signs NEG ZERO POS 51

Data Type Abstraction 2002 Collapses data domains via abstract interpretation: Code Data domains int x = 0; if (x == 0) x = x + 1; (n<0) : NEG (n==0): ZERO (n>0) : POS Signs x = ZERO; if (Signs. eq(x, ZERO)) x = Signs. add(x, POS); 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 Signs NEG ZERO POS 51

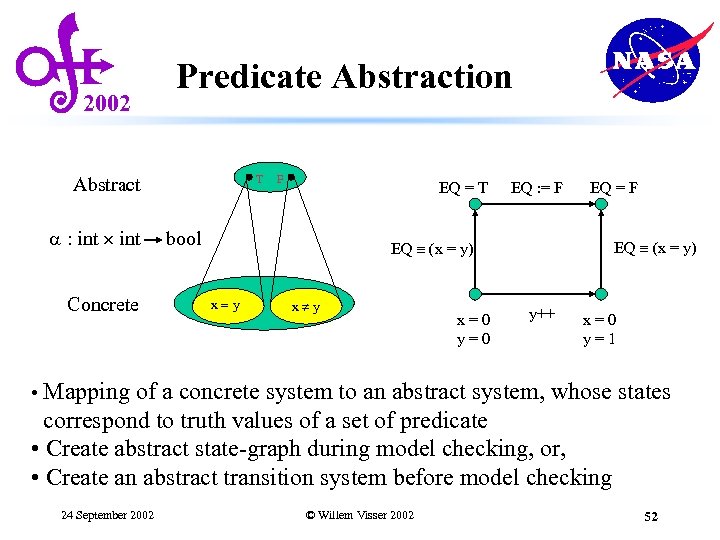

2002 Predicate Abstraction T Abstract a : int Concrete F EQ = T bool EQ : = F EQ (x = y) x=y x y x=0 y++ x=0 y=1 • Mapping of a concrete system to an abstract system, whose states correspond to truth values of a set of predicate • Create abstract state-graph during model checking, or, • Create an abstract transition system before model checking 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 52

2002 Predicate Abstraction T Abstract a : int Concrete F EQ = T bool EQ : = F EQ (x = y) x=y x y x=0 y++ x=0 y=1 • Mapping of a concrete system to an abstract system, whose states correspond to truth values of a set of predicate • Create abstract state-graph during model checking, or, • Create an abstract transition system before model checking 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 52

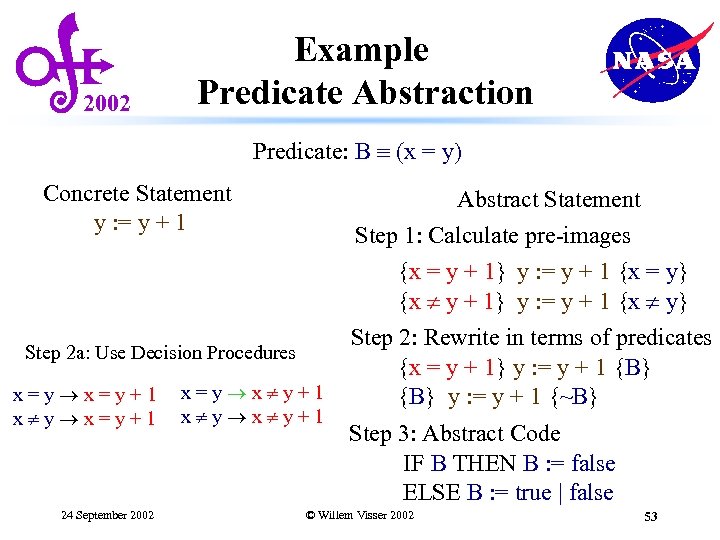

2002 Example Predicate Abstraction Predicate: B (x = y) Concrete Statement y : = y + 1 Step 2 a: Use Decision Procedures x=y+1 x y x=y+1 24 September 2002 x=y x y+1 Abstract Statement Step 1: Calculate pre-images {x = y + 1} y : = y + 1 {x = y} {x y + 1} y : = y + 1 {x y} Step 2: Rewrite in terms of predicates {x = y + 1} y : = y + 1 {B} y : = y + 1 {~B} Step 3: Abstract Code IF B THEN B : = false ELSE B : = true | false © Willem Visser 2002 53

2002 Example Predicate Abstraction Predicate: B (x = y) Concrete Statement y : = y + 1 Step 2 a: Use Decision Procedures x=y+1 x y x=y+1 24 September 2002 x=y x y+1 Abstract Statement Step 1: Calculate pre-images {x = y + 1} y : = y + 1 {x = y} {x y + 1} y : = y + 1 {x y} Step 2: Rewrite in terms of predicates {x = y + 1} y : = y + 1 {B} y : = y + 1 {~B} Step 3: Abstract Code IF B THEN B : = false ELSE B : = true | false © Willem Visser 2002 53

![Example of Infeasible Counter-example 2002 {NEG, ZERO, POS} [1] if (-2 + 3 > Example of Infeasible Counter-example 2002 {NEG, ZERO, POS} [1] if (-2 + 3 >](https://present5.com/presentation/f629f287936a6cd39231e6621f5b92da/image-54.jpg) Example of Infeasible Counter-example 2002 {NEG, ZERO, POS} [1] if (-2 + 3 > 0) then [2] assert(true); else [3] assert(false); Signs: n < 0 -> neg 0 -> zero n > 0 -> pos [1] if(Signs. gt(Signs. add(NEG, POS), ZERO)) then [2] assert(true); else [3] assert(false); In ib as fe le [1]: te un co 24 September 2002 [2]: © Willem Visser 2002 [3]: X e pl am ex r- [2]: 54

Example of Infeasible Counter-example 2002 {NEG, ZERO, POS} [1] if (-2 + 3 > 0) then [2] assert(true); else [3] assert(false); Signs: n < 0 -> neg 0 -> zero n > 0 -> pos [1] if(Signs. gt(Signs. add(NEG, POS), ZERO)) then [2] assert(true); else [3] assert(false); In ib as fe le [1]: te un co 24 September 2002 [2]: © Willem Visser 2002 [3]: X e pl am ex r- [2]: 54

Overview 2002 • Introduction to Model Checking • Program Model Checking – Major Trends – A Brief History – Current Trends • Custom-made model checkers for programs • Abstraction • SLAM – Abstraction Refinement • JPF • Summary • Examples of other software analyses • Case Studies • Future of Software Model Checking 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 55

Overview 2002 • Introduction to Model Checking • Program Model Checking – Major Trends – A Brief History – Current Trends • Custom-made model checkers for programs • Abstraction • SLAM – Abstraction Refinement • JPF • Summary • Examples of other software analyses • Case Studies • Future of Software Model Checking 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 55

![SLAM 2002 C Program annotated with API usage rules void add(Object o) { buffer[head] SLAM 2002 C Program annotated with API usage rules void add(Object o) { buffer[head]](https://present5.com/presentation/f629f287936a6cd39231e6621f5b92da/image-56.jpg) SLAM 2002 C Program annotated with API usage rules void add(Object o) { buffer[head] = o; head = (head+1)%size; } Simplified View Predicate Abstraction C 2 BP Predicates Object take() { … tail=(tail+1)%size; return buffer[tail]; } Symbolic Execution NEWTON Custom Model Checker BEBOP Correct Error-trace False Error-trace is Feasible 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 56

SLAM 2002 C Program annotated with API usage rules void add(Object o) { buffer[head] = o; head = (head+1)%size; } Simplified View Predicate Abstraction C 2 BP Predicates Object take() { … tail=(tail+1)%size; return buffer[tail]; } Symbolic Execution NEWTON Custom Model Checker BEBOP Correct Error-trace False Error-trace is Feasible 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 56

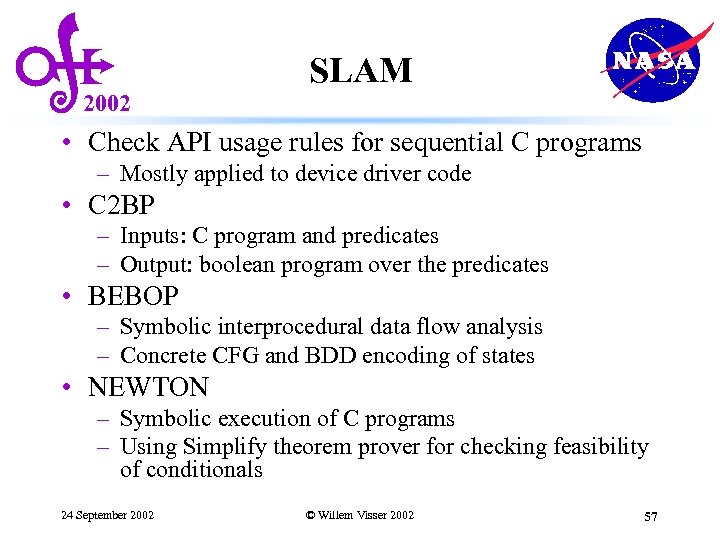

2002 SLAM • Check API usage rules for sequential C programs – Mostly applied to device driver code • C 2 BP – Inputs: C program and predicates – Output: boolean program over the predicates • BEBOP – Symbolic interprocedural data flow analysis – Concrete CFG and BDD encoding of states • NEWTON – Symbolic execution of C programs – Using Simplify theorem prover for checking feasibility of conditionals 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 57

2002 SLAM • Check API usage rules for sequential C programs – Mostly applied to device driver code • C 2 BP – Inputs: C program and predicates – Output: boolean program over the predicates • BEBOP – Symbolic interprocedural data flow analysis – Concrete CFG and BDD encoding of states • NEWTON – Symbolic execution of C programs – Using Simplify theorem prover for checking feasibility of conditionals 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 57

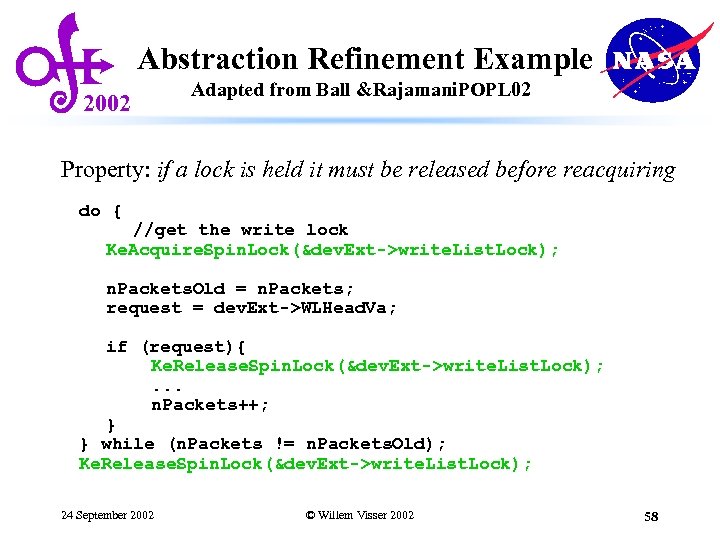

Abstraction Refinement Example 2002 Adapted from Ball &Rajamani. POPL 02 Property: if a lock is held it must be released before reacquiring do { //get the write lock Ke. Acquire. Spin. Lock(&dev. Ext->write. List. Lock); n. Packets. Old = n. Packets; request = dev. Ext->WLHead. Va; if (request){ Ke. Release. Spin. Lock(&dev. Ext->write. List. Lock); . . . n. Packets++; } } while (n. Packets != n. Packets. Old); Ke. Release. Spin. Lock(&dev. Ext->write. List. Lock); 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 58

Abstraction Refinement Example 2002 Adapted from Ball &Rajamani. POPL 02 Property: if a lock is held it must be released before reacquiring do { //get the write lock Ke. Acquire. Spin. Lock(&dev. Ext->write. List. Lock); n. Packets. Old = n. Packets; request = dev. Ext->WLHead. Va; if (request){ Ke. Release. Spin. Lock(&dev. Ext->write. List. Lock); . . . n. Packets++; } } while (n. Packets != n. Packets. Old); Ke. Release. Spin. Lock(&dev. Ext->write. List. Lock); 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 58

![Initial Abstraction and Model Checking 2002 Boolean Program [1] do //get the write lock Initial Abstraction and Model Checking 2002 Boolean Program [1] do //get the write lock](https://present5.com/presentation/f629f287936a6cd39231e6621f5b92da/image-59.jpg) Initial Abstraction and Model Checking 2002 Boolean Program [1] do //get the write lock [2] Acquire. Lock(); [3] if (*) then [4] Release. Lock(); fi [5] while (*); [6] Release. Lock(); Error-trace : 1, 2, 3, 5, 1, 2 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 59

Initial Abstraction and Model Checking 2002 Boolean Program [1] do //get the write lock [2] Acquire. Lock(); [3] if (*) then [4] Release. Lock(); fi [5] while (*); [6] Release. Lock(); Error-trace : 1, 2, 3, 5, 1, 2 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 59

![2002 Symbolic Execution [1] do { [2] Ke. Acquire. Spin. Lock(&dev. Ext->write. List. Lock); 2002 Symbolic Execution [1] do { [2] Ke. Acquire. Spin. Lock(&dev. Ext->write. List. Lock);](https://present5.com/presentation/f629f287936a6cd39231e6621f5b92da/image-60.jpg) 2002 Symbolic Execution [1] do { [2] Ke. Acquire. Spin. Lock(&dev. Ext->write. List. Lock); n. Packets. Old = n. Packets; request = dev. Ext->WLHead. Va; [3] if (request){ [4] Ke. Release. Spin. Lock(&dev. Ext->write. List. Lock); . . . n. Packets++; } [5] } while (n. Packets != n. Packets. Old); [6] Ke. Release. Spin. Lock(&dev. Ext->write. List. Lock); Symbolic execution of 1, 2, 3, 5, 1, 2 shows that when 5 is executed n. Packets == n. Packets. Old hence the path is infeasible. The predicate n. Packets == n. Packets. Old is then added and used during predicate abstraction 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 60

2002 Symbolic Execution [1] do { [2] Ke. Acquire. Spin. Lock(&dev. Ext->write. List. Lock); n. Packets. Old = n. Packets; request = dev. Ext->WLHead. Va; [3] if (request){ [4] Ke. Release. Spin. Lock(&dev. Ext->write. List. Lock); . . . n. Packets++; } [5] } while (n. Packets != n. Packets. Old); [6] Ke. Release. Spin. Lock(&dev. Ext->write. List. Lock); Symbolic execution of 1, 2, 3, 5, 1, 2 shows that when 5 is executed n. Packets == n. Packets. Old hence the path is infeasible. The predicate n. Packets == n. Packets. Old is then added and used during predicate abstraction 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 60

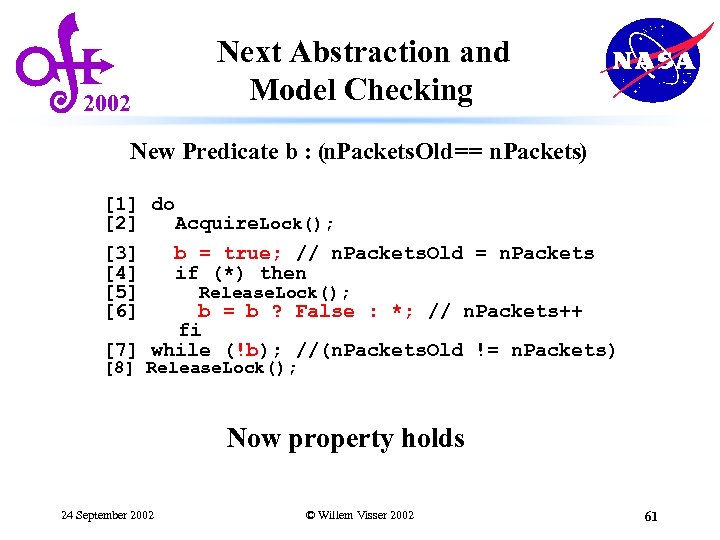

2002 Next Abstraction and Model Checking New Predicate b : (n. Packets. Old == n. Packets) [1] do [2] Acquire. Lock(); [3] b = true; // n. Packets. Old = n. Packets [4] if (*) then [5] Release. Lock(); [6] b = b ? False : *; // n. Packets++ fi [7] while (!b); //(n. Packets. Old != n. Packets) [8] Release. Lock(); Now property holds 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 61

2002 Next Abstraction and Model Checking New Predicate b : (n. Packets. Old == n. Packets) [1] do [2] Acquire. Lock(); [3] b = true; // n. Packets. Old = n. Packets [4] if (*) then [5] Release. Lock(); [6] b = b ? False : *; // n. Packets++ fi [7] while (!b); //(n. Packets. Old != n. Packets) [8] Release. Lock(); Now property holds 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 61

Overview 2002 • Introduction to Model Checking • Program Model Checking – Major Trends – A Brief History – Current Trends • Custom-made model checkers for programs • SLAM • JPF – – Abstractions Partial-order and symmetry reductions Heuristics New Stuff • Summary • Examples of other software analyses • Case Studies • Future of Software Model Checking 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 62

Overview 2002 • Introduction to Model Checking • Program Model Checking – Major Trends – A Brief History – Current Trends • Custom-made model checkers for programs • SLAM • JPF – – Abstractions Partial-order and symmetry reductions Heuristics New Stuff • Summary • Examples of other software analyses • Case Studies • Future of Software Model Checking 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 62

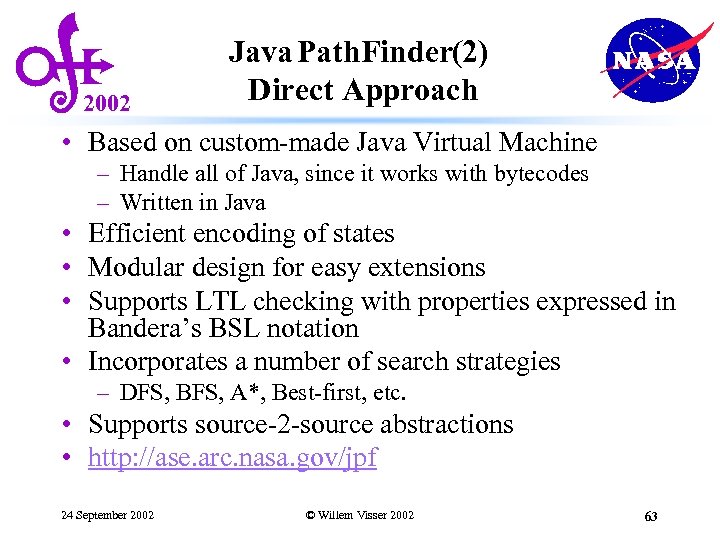

2002 Java Path. Finder(2) Direct Approach • Based on custom-made Java Virtual Machine – Handle all of Java, since it works with bytecodes – Written in Java • Efficient encoding of states • Modular design for easy extensions • Supports LTL checking with properties expressed in Bandera’s BSL notation • Incorporates a number of search strategies – DFS, BFS, A*, Best-first, etc. • Supports source-2 -source abstractions • http: //ase. arc. nasa. gov/jpf 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 63

2002 Java Path. Finder(2) Direct Approach • Based on custom-made Java Virtual Machine – Handle all of Java, since it works with bytecodes – Written in Java • Efficient encoding of states • Modular design for easy extensions • Supports LTL checking with properties expressed in Bandera’s BSL notation • Incorporates a number of search strategies – DFS, BFS, A*, Best-first, etc. • Supports source-2 -source abstractions • http: //ase. arc. nasa. gov/jpf 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 63

![2002 Java Path. Finder(JPF) Java Code Bytecode void add(Object o) { buffer[head] = o; 2002 Java Path. Finder(JPF) Java Code Bytecode void add(Object o) { buffer[head] = o;](https://present5.com/presentation/f629f287936a6cd39231e6621f5b92da/image-64.jpg) 2002 Java Path. Finder(JPF) Java Code Bytecode void add(Object o) { buffer[head] = o; head = (head+1)%size; } Object take() { … tail=(tail+1)%size; return buffer[tail]; } JAVAC 0: 1: 2: 5: 8: 9: 10: iconst_0 istore_2 goto #39 getstatic aload_0 iload_2 aaload JVM Model Checker Special JVM 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 64

2002 Java Path. Finder(JPF) Java Code Bytecode void add(Object o) { buffer[head] = o; head = (head+1)%size; } Object take() { … tail=(tail+1)%size; return buffer[tail]; } JAVAC 0: 1: 2: 5: 8: 9: 10: iconst_0 istore_2 goto #39 getstatic aload_0 iload_2 aaload JVM Model Checker Special JVM 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 64

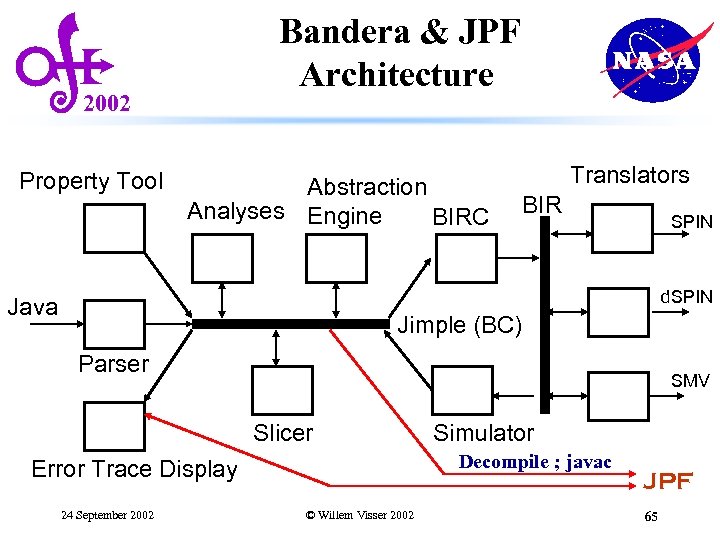

Bandera & JPF Architecture 2002 Property Tool Abstraction Analyses Engine BIRC Translators BIR SPIN d. SPIN Java Jimple (BC) Parser SMV Slicer Decompile ; javac Error Trace Display 24 September 2002 Simulator © Willem Visser 2002 JPF 65

Bandera & JPF Architecture 2002 Property Tool Abstraction Analyses Engine BIRC Translators BIR SPIN d. SPIN Java Jimple (BC) Parser SMV Slicer Decompile ; javac Error Trace Display 24 September 2002 Simulator © Willem Visser 2002 JPF 65

2002 Key Points • Models can be infinite state – Unbounded objects, threads, … – Depth-first state generation (explicit-state) – Verification requires abstraction • Handle full Java language – but only for closed systems – Cannot handle native code • no Input/output through GUIs, files, Networks, … • Must be modeled by java code instead • Allows Nondeterministic Environments – JPF traps special nondeterministic methods • Checks for User-defined assertions, deadlock and LTL properties 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 66

2002 Key Points • Models can be infinite state – Unbounded objects, threads, … – Depth-first state generation (explicit-state) – Verification requires abstraction • Handle full Java language – but only for closed systems – Cannot handle native code • no Input/output through GUIs, files, Networks, … • Must be modeled by java code instead • Allows Nondeterministic Environments – JPF traps special nondeterministic methods • Checks for User-defined assertions, deadlock and LTL properties 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 66

Java Extensions -Verify Class 2002 • Used for annotations • Atomicity – begin. Atomic(), end. Atomic() • Nondeterminism – int random(int); boolean random. Bool(); Object random. Object(String cname); • Properties – Assert. True(boolean cond) • Miscellaneous – Dump states, print, Daikon logs, … 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 67

Java Extensions -Verify Class 2002 • Used for annotations • Atomicity – begin. Atomic(), end. Atomic() • Nondeterminism – int random(int); boolean random. Bool(); Object random. Object(String cname); • Properties – Assert. True(boolean cond) • Miscellaneous – Dump states, print, Daikon logs, … 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 67

2002 JPF Technologies • Predicate abstraction and type based abstractions • Partial order and symmetry reductions • Slicing • Heuristic Search • New Stuff – Symbolic Execution – Error Explanations 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 68

2002 JPF Technologies • Predicate abstraction and type based abstractions • Partial order and symmetry reductions • Slicing • Heuristic Search • New Stuff – Symbolic Execution – Error Explanations 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 68

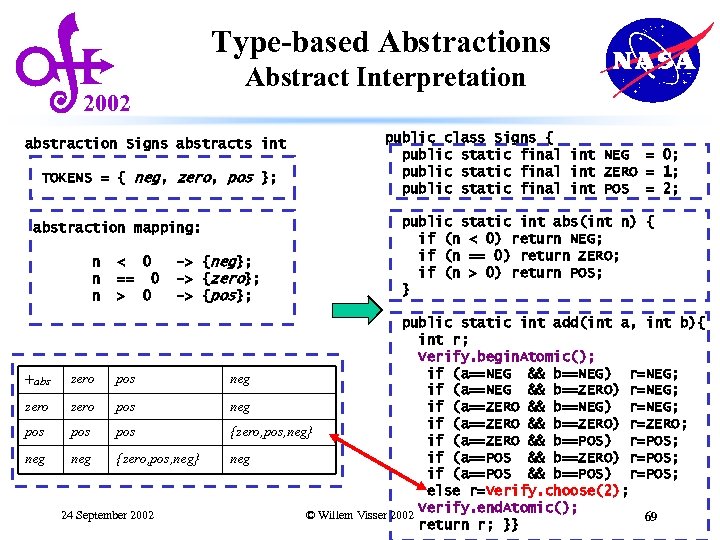

Type-based Abstractions Abstract Interpretation 2002 abstraction Signs abstracts int TOKENS = { neg, zero, pos }; abstraction mapping: n n n < 0 == 0 > 0 -> {neg}; -> {zero}; -> {pos}; +abs zero pos pos neg {zero, pos, neg} 24 September 2002 public class Signs { public static final int NEG = 0; public static final int ZERO = 1; public static final int POS = 2; public static int abs(int n) { if (n < 0) return NEG; if (n == 0) return ZERO; if (n > 0) return POS; } public static int add(int a, int b){ int r; Verify. begin. Atomic(); if (a==NEG && b==NEG) r=NEG; neg if (a==NEG && b==ZERO) r=NEG; neg if (a==ZERO && b==NEG) r=NEG; if (a==ZERO && b==ZERO) r=ZERO; {zero, pos, neg} if (a==ZERO && b==POS) r=POS; if (a==POS && b==ZERO) r=POS; neg if (a==POS && b==POS) r=POS; else r=Verify. choose(2); Verify. end. Atomic(); © Willem Visser 2002 69 return r; }}

Type-based Abstractions Abstract Interpretation 2002 abstraction Signs abstracts int TOKENS = { neg, zero, pos }; abstraction mapping: n n n < 0 == 0 > 0 -> {neg}; -> {zero}; -> {pos}; +abs zero pos pos neg {zero, pos, neg} 24 September 2002 public class Signs { public static final int NEG = 0; public static final int ZERO = 1; public static final int POS = 2; public static int abs(int n) { if (n < 0) return NEG; if (n == 0) return ZERO; if (n > 0) return POS; } public static int add(int a, int b){ int r; Verify. begin. Atomic(); if (a==NEG && b==NEG) r=NEG; neg if (a==NEG && b==ZERO) r=NEG; neg if (a==ZERO && b==NEG) r=NEG; if (a==ZERO && b==ZERO) r=ZERO; {zero, pos, neg} if (a==ZERO && b==POS) r=POS; if (a==POS && b==ZERO) r=POS; neg if (a==POS && b==POS) r=POS; else r=Verify. choose(2); Verify. end. Atomic(); © Willem Visser 2002 69 return r; }}

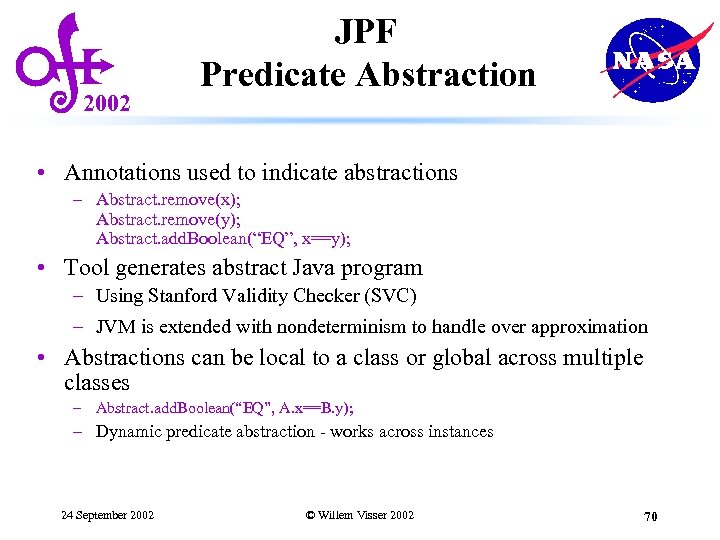

2002 JPF Predicate Abstraction • Annotations used to indicate abstractions – Abstract. remove(x); Abstract. remove(y); Abstract. add. Boolean(“EQ”, x==y); • Tool generates abstract Java program – Using Stanford Validity Checker (SVC) – JVM is extended with nondeterminism to handle over approximation • Abstractions can be local to a class or global across multiple classes – Abstract. add. Boolean(“EQ”, A. x==B. y); – Dynamic predicate abstraction - works across instances 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 70

2002 JPF Predicate Abstraction • Annotations used to indicate abstractions – Abstract. remove(x); Abstract. remove(y); Abstract. add. Boolean(“EQ”, x==y); • Tool generates abstract Java program – Using Stanford Validity Checker (SVC) – JVM is extended with nondeterminism to handle over approximation • Abstractions can be local to a class or global across multiple classes – Abstract. add. Boolean(“EQ”, A. x==B. y); – Dynamic predicate abstraction - works across instances 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 70

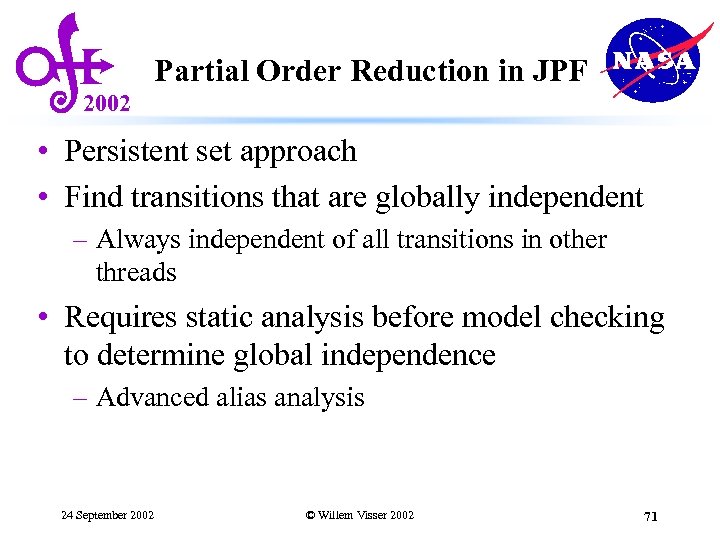

Partial Order Reduction in JPF 2002 • Persistent set approach • Find transitions that are globally independent – Always independent of all transitions in other threads • Requires static analysis before model checking to determine global independence – Advanced alias analysis 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 71

Partial Order Reduction in JPF 2002 • Persistent set approach • Find transitions that are globally independent – Always independent of all transitions in other threads • Requires static analysis before model checking to determine global independence – Advanced alias analysis 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 71

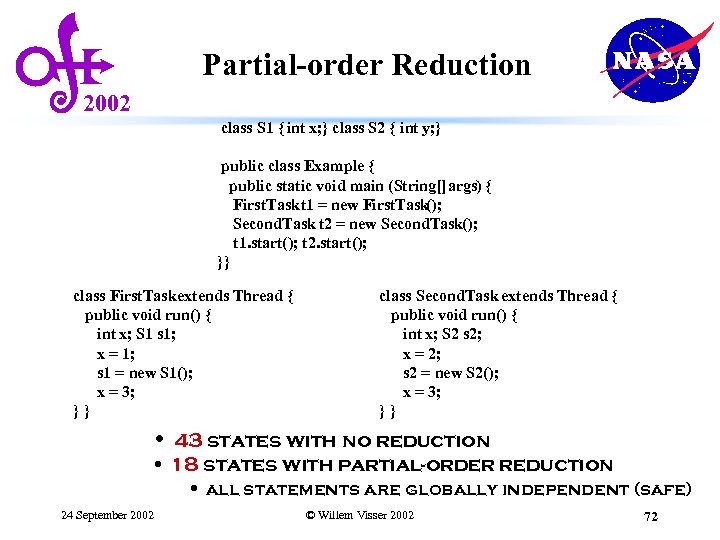

Partial-order Reduction 2002 class S 1 { int x; } class S 2 { int y; } public class Example { public static void main (String[] args) { First. Task t 1 = new First. Task (); Second. Task t 2 = new Second. Task(); t 1. start(); t 2. start(); }} class First. Task extends Thread { public void run() { int x; S 1 s 1; x = 1; s 1 = new S 1(); x = 3; }} class Second. Task extends Thread { public void run() { int x; S 2 s 2; x = 2; s 2 = new S 2(); x = 3; }} • 43 states with no reduction • 18 states with partial-order reduction • all statements are globally independent (safe) 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 72

Partial-order Reduction 2002 class S 1 { int x; } class S 2 { int y; } public class Example { public static void main (String[] args) { First. Task t 1 = new First. Task (); Second. Task t 2 = new Second. Task(); t 1. start(); t 2. start(); }} class First. Task extends Thread { public void run() { int x; S 1 s 1; x = 1; s 1 = new S 1(); x = 3; }} class Second. Task extends Thread { public void run() { int x; S 2 s 2; x = 2; s 2 = new S 2(); x = 3; }} • 43 states with no reduction • 18 states with partial-order reduction • all statements are globally independent (safe) 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 72

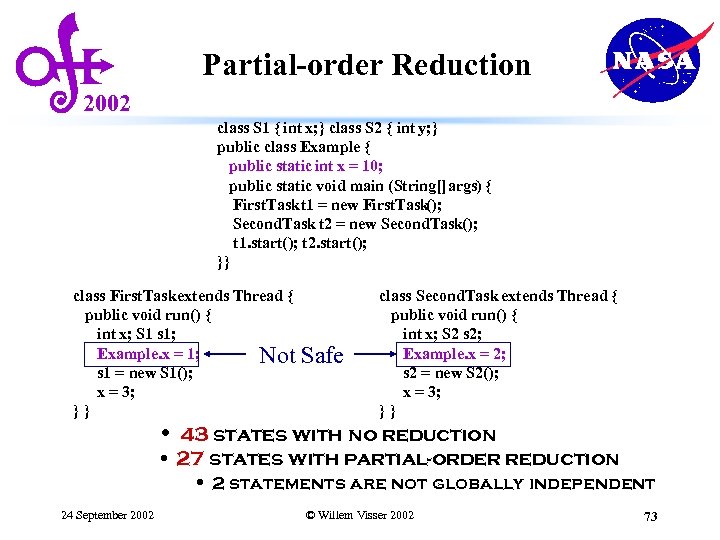

Partial-order Reduction 2002 class S 1 { int x; } class S 2 { int y; } public class Example { public static int x = 10; public static void main (String[] args) { First. Task t 1 = new First. Task (); Second. Task t 2 = new Second. Task(); t 1. start(); t 2. start(); }} class First. Task extends Thread { public void run() { int x; S 1 s 1; Example. x = 1; Not s 1 = new S 1(); x = 3; }} Safe class Second. Task extends Thread { public void run() { int x; S 2 s 2; Example. x = 2; s 2 = new S 2(); x = 3; }} • 43 states with no reduction • 27 states with partial-order reduction • 2 statements are not globally independent 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 73

Partial-order Reduction 2002 class S 1 { int x; } class S 2 { int y; } public class Example { public static int x = 10; public static void main (String[] args) { First. Task t 1 = new First. Task (); Second. Task t 2 = new Second. Task(); t 1. start(); t 2. start(); }} class First. Task extends Thread { public void run() { int x; S 1 s 1; Example. x = 1; Not s 1 = new S 1(); x = 3; }} Safe class Second. Task extends Thread { public void run() { int x; S 2 s 2; Example. x = 2; s 2 = new S 2(); x = 3; }} • 43 states with no reduction • 27 states with partial-order reduction • 2 statements are not globally independent 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 73

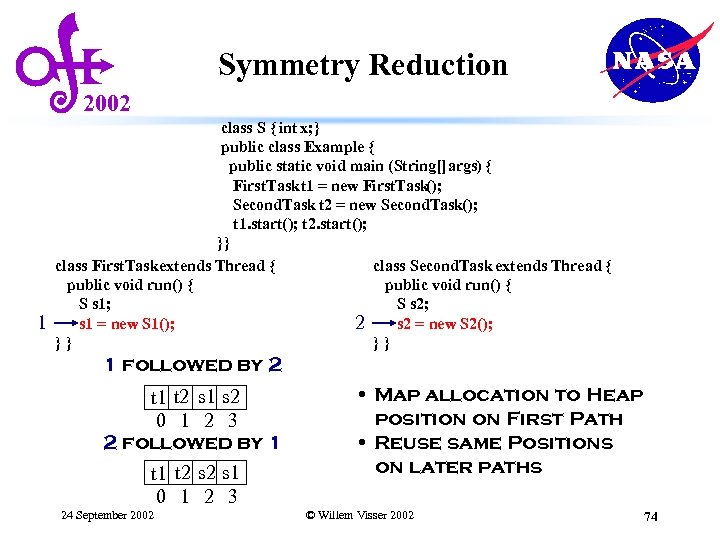

Symmetry Reduction 2002 1 class S { int x; } public class Example { public static void main (String[] args) { First. Task t 1 = new First. Task (); Second. Task t 2 = new Second. Task(); t 1. start(); t 2. start(); }} class First. Task extends Thread { class Second. Task extends Thread { public void run() { S s 1; S s 2; s 1 = new S 1(); s 2 = new S 2(); 2 }} }} 1 followed by 2 t 1 t 2 s 1 s 2 0 1 2 3 2 followed by 1 t 2 s 1 0 1 2 3 24 September 2002 • Map allocation to Heap position on First Path • Reuse same Positions on later paths © Willem Visser 2002 74

Symmetry Reduction 2002 1 class S { int x; } public class Example { public static void main (String[] args) { First. Task t 1 = new First. Task (); Second. Task t 2 = new Second. Task(); t 1. start(); t 2. start(); }} class First. Task extends Thread { class Second. Task extends Thread { public void run() { S s 1; S s 2; s 1 = new S 1(); s 2 = new S 2(); 2 }} }} 1 followed by 2 t 1 t 2 s 1 s 2 0 1 2 3 2 followed by 1 t 2 s 1 0 1 2 3 24 September 2002 • Map allocation to Heap position on First Path • Reuse same Positions on later paths © Willem Visser 2002 74

![2002 Garbage Collection class gc { public static void main (String[] args) { while(true) 2002 Garbage Collection class gc { public static void main (String[] args) { while(true)](https://present5.com/presentation/f629f287936a6cd39231e6621f5b92da/image-75.jpg) 2002 Garbage Collection class gc { public static void main (String[] args) { while(true) { System. out. println(“ 0”); }}} • Infinite State program • Garbage makes the state grow… • JPF supports • Mark-and-Sweep • Reference counting 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 75

2002 Garbage Collection class gc { public static void main (String[] args) { while(true) { System. out. println(“ 0”); }}} • Infinite State program • Garbage makes the state grow… • JPF supports • Mark-and-Sweep • Reference counting 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 75

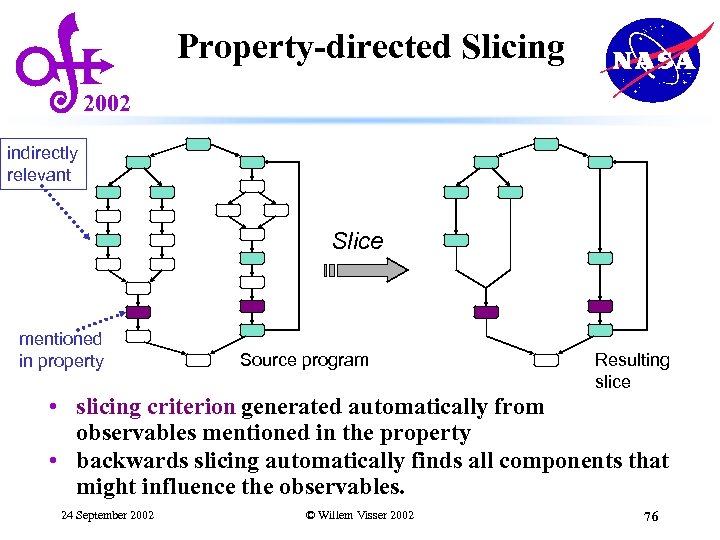

Property-directed Slicing 2002 indirectly relevant Slice mentioned in property Source program Resulting slice • slicing criterion generated automatically from observables mentioned in the property • backwards slicing automatically finds all components that might influence the observables. 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 76

Property-directed Slicing 2002 indirectly relevant Slice mentioned in property Source program Resulting slice • slicing criterion generated automatically from observables mentioned in the property • backwards slicing automatically finds all components that might influence the observables. 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 76

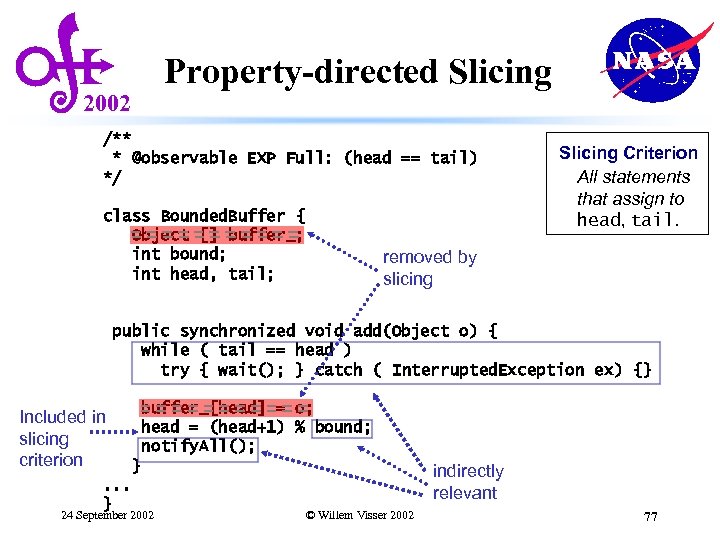

Property-directed Slicing 2002 /** * @observable EXP Full: (head == tail) */ class Bounded. Buffer { Object [] buffer_; int bound; int head, tail; Slicing Criterion All statements that assign to head, tail. removed by slicing public synchronized void add(Object o) { while ( tail == head ) try { wait(); } catch ( Interrupted. Exception ex) {} buffer_[head] = o; head = (head+1) % bound; notify. All(); Included in slicing criterion. . . } } 24 September 2002 indirectly relevant © Willem Visser 2002 77

Property-directed Slicing 2002 /** * @observable EXP Full: (head == tail) */ class Bounded. Buffer { Object [] buffer_; int bound; int head, tail; Slicing Criterion All statements that assign to head, tail. removed by slicing public synchronized void add(Object o) { while ( tail == head ) try { wait(); } catch ( Interrupted. Exception ex) {} buffer_[head] = o; head = (head+1) % bound; notify. All(); Included in slicing criterion. . . } } 24 September 2002 indirectly relevant © Willem Visser 2002 77

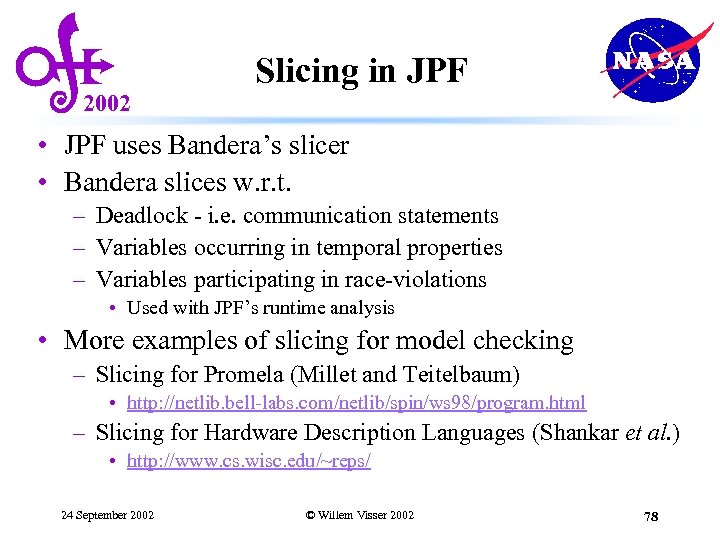

2002 Slicing in JPF • JPF uses Bandera’s slicer • Bandera slices w. r. t. – Deadlock - i. e. communication statements – Variables occurring in temporal properties – Variables participating in race-violations • Used with JPF’s runtime analysis • More examples of slicing for model checking – Slicing for Promela (Millet and Teitelbaum) • http: //netlib. bell-labs. com/netlib/spin/ws 98/program. html – Slicing for Hardware Description Languages (Shankar et al. ) • http: //www. cs. wisc. edu/~reps/ 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 78

2002 Slicing in JPF • JPF uses Bandera’s slicer • Bandera slices w. r. t. – Deadlock - i. e. communication statements – Variables occurring in temporal properties – Variables participating in race-violations • Used with JPF’s runtime analysis • More examples of slicing for model checking – Slicing for Promela (Millet and Teitelbaum) • http: //netlib. bell-labs. com/netlib/spin/ws 98/program. html – Slicing for Hardware Description Languages (Shankar et al. ) • http: //www. cs. wisc. edu/~reps/ 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 78

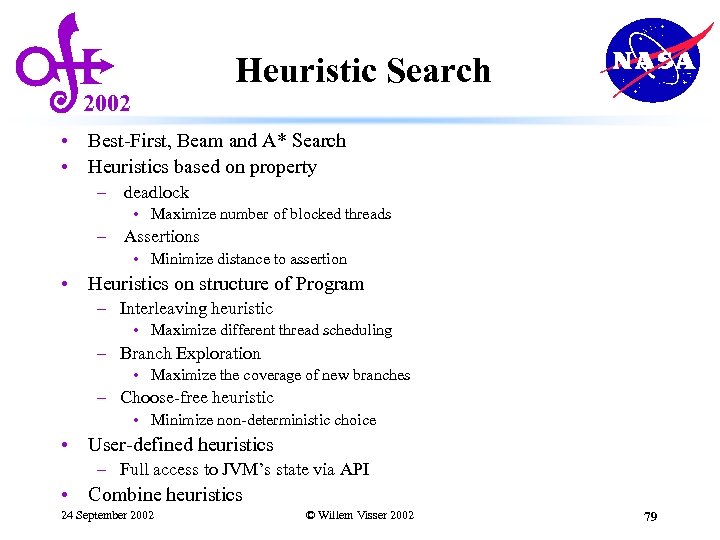

Heuristic Search 2002 • Best-First, Beam and A* Search • Heuristics based on property – deadlock • Maximize number of blocked threads – Assertions • Minimize distance to assertion • Heuristics on structure of Program – Interleaving heuristic • Maximize different thread scheduling – Branch Exploration • Maximize the coverage of new branches – Choose-free heuristic • Minimize non-deterministic choice • User-defined heuristics – Full access to JVM’s state via API • Combine heuristics 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 79

Heuristic Search 2002 • Best-First, Beam and A* Search • Heuristics based on property – deadlock • Maximize number of blocked threads – Assertions • Minimize distance to assertion • Heuristics on structure of Program – Interleaving heuristic • Maximize different thread scheduling – Branch Exploration • Maximize the coverage of new branches – Choose-free heuristic • Minimize non-deterministic choice • User-defined heuristics – Full access to JVM’s state via API • Combine heuristics 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 79

![2002 Choose-free state space search • Theorem [Saidi: SAS’ 00] Every path in the 2002 Choose-free state space search • Theorem [Saidi: SAS’ 00] Every path in the](https://present5.com/presentation/f629f287936a6cd39231e6621f5b92da/image-80.jpg) 2002 Choose-free state space search • Theorem [Saidi: SAS’ 00] Every path in the abstracted program where all assignments are deterministic is a path in the concrete program. • Bias the model checker – to look only at paths that do not include instructions that introduce non-determinism • JPF model checker modified – to detect non-deterministic choice and backtrack from those points 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 80

2002 Choose-free state space search • Theorem [Saidi: SAS’ 00] Every path in the abstracted program where all assignments are deterministic is a path in the concrete program. • Bias the model checker – to look only at paths that do not include instructions that introduce non-determinism • JPF model checker modified – to detect non-deterministic choice and backtrack from those points 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 80

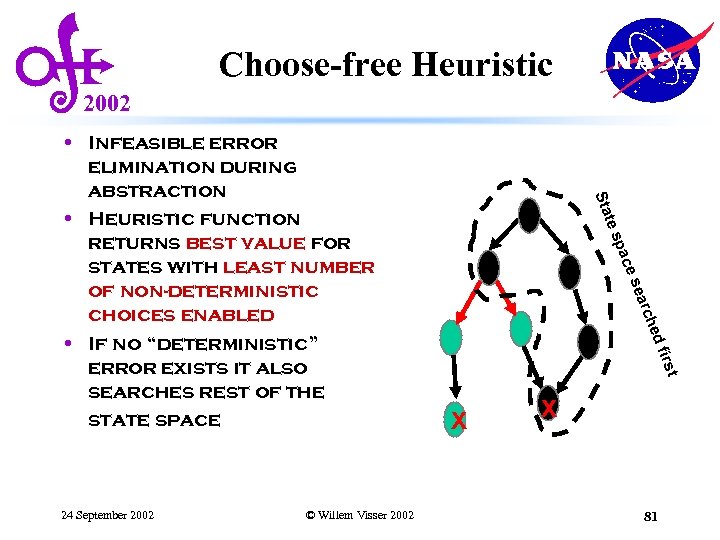

Choose-free Heuristic 2002 che ear es rst d fi © Willem Visser 2002 pac 24 September 2002 te s Sta • Infeasible error elimination during abstraction • Heuristic function returns best value for states with least number of non-deterministic choices enabled • If no “deterministic” error exists it also searches rest of the state space X X 81

Choose-free Heuristic 2002 che ear es rst d fi © Willem Visser 2002 pac 24 September 2002 te s Sta • Infeasible error elimination during abstraction • Heuristic function returns best value for states with least number of non-deterministic choices enabled • If no “deterministic” error exists it also searches rest of the state space X X 81

2002 Test Coverage for Model Checking • Reality check: – Model Checkers run out of memory OFTEN! • If no error was found, how confident can we be that none exists? – Require coverage measure • JPF extended with Branch coverage calculations • Can the coverage measure guide the model checker – Yes, as a heuristic – Better heuristic values are given for least explored branches 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 82

2002 Test Coverage for Model Checking • Reality check: – Model Checkers run out of memory OFTEN! • If no error was found, how confident can we be that none exists? – Require coverage measure • JPF extended with Branch coverage calculations • Can the coverage measure guide the model checker – Yes, as a heuristic – Better heuristic values are given for least explored branches 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 82

2002 Concurrency Bugs • Often due to unanticipated interleaving • Increased thread interleaving might expose them • Interleaving heuristic – Executions in which context is switched more often are given better heuristic values 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 83

2002 Concurrency Bugs • Often due to unanticipated interleaving • Increased thread interleaving might expose them • Interleaving heuristic – Executions in which context is switched more often are given better heuristic values 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 83

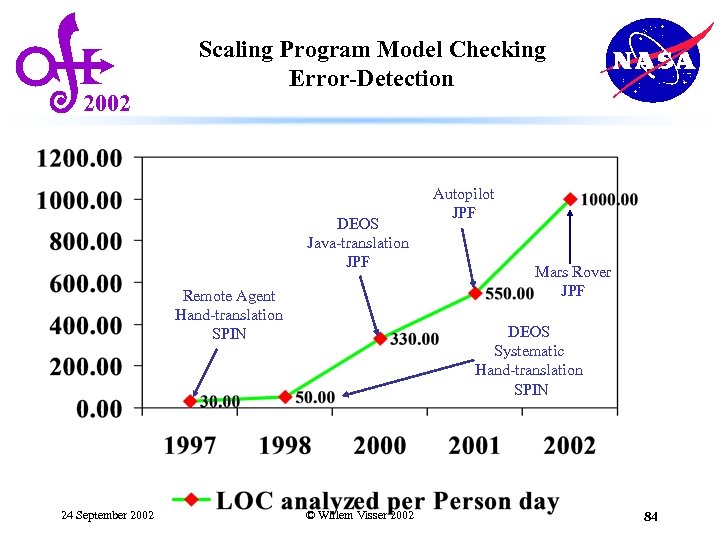

2002 Scaling Program Model Checking Error-Detection DEOS Java-translation JPF Remote Agent Hand-translation SPIN 24 September 2002 Autopilot JPF Mars Rover JPF DEOS Systematic Hand-translation SPIN © Willem Visser 2002 84

2002 Scaling Program Model Checking Error-Detection DEOS Java-translation JPF Remote Agent Hand-translation SPIN 24 September 2002 Autopilot JPF Mars Rover JPF DEOS Systematic Hand-translation SPIN © Willem Visser 2002 84

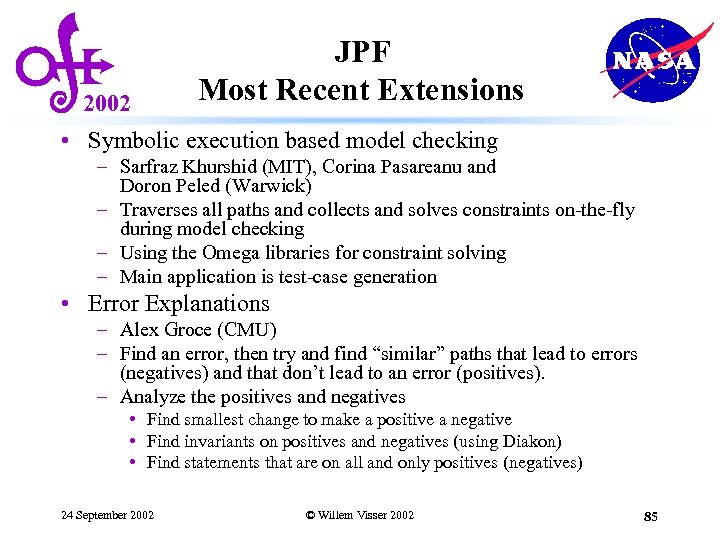

2002 JPF Most Recent Extensions • Symbolic execution based model checking – Sarfraz Khurshid (MIT), Corina Pasareanu and Doron Peled (Warwick) – Traverses all paths and collects and solves constraints on-the-fly during model checking – Using the Omega libraries for constraint solving – Main application is test-case generation • Error Explanations – Alex Groce (CMU) – Find an error, then try and find “similar” paths that lead to errors (negatives) and that don’t lead to an error (positives). – Analyze the positives and negatives • Find smallest change to make a positive a negative • Find invariants on positives and negatives (using Diakon) • Find statements that are on all and only positives (negatives) 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 85

2002 JPF Most Recent Extensions • Symbolic execution based model checking – Sarfraz Khurshid (MIT), Corina Pasareanu and Doron Peled (Warwick) – Traverses all paths and collects and solves constraints on-the-fly during model checking – Using the Omega libraries for constraint solving – Main application is test-case generation • Error Explanations – Alex Groce (CMU) – Find an error, then try and find “similar” paths that lead to errors (negatives) and that don’t lead to an error (positives). – Analyze the positives and negatives • Find smallest change to make a positive a negative • Find invariants on positives and negatives (using Diakon) • Find statements that are on all and only positives (negatives) 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 85

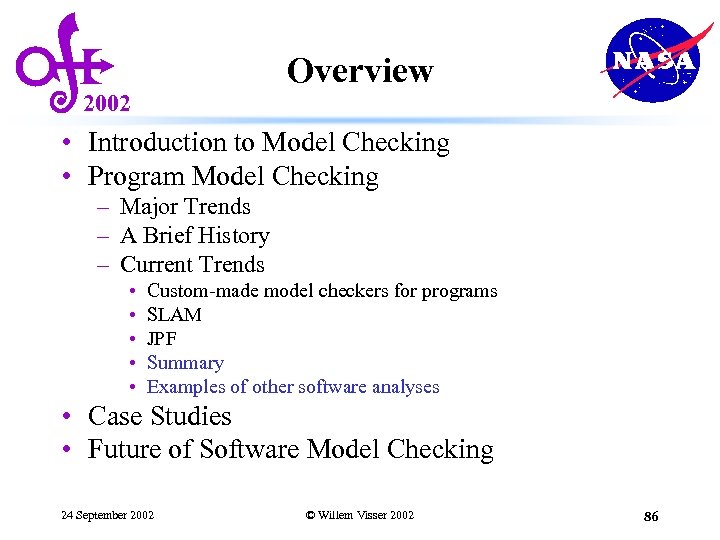

Overview 2002 • Introduction to Model Checking • Program Model Checking – Major Trends – A Brief History – Current Trends • • • Custom-made model checkers for programs SLAM JPF Summary Examples of other software analyses • Case Studies • Future of Software Model Checking 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 86

Overview 2002 • Introduction to Model Checking • Program Model Checking – Major Trends – A Brief History – Current Trends • • • Custom-made model checkers for programs SLAM JPF Summary Examples of other software analyses • Case Studies • Future of Software Model Checking 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 86

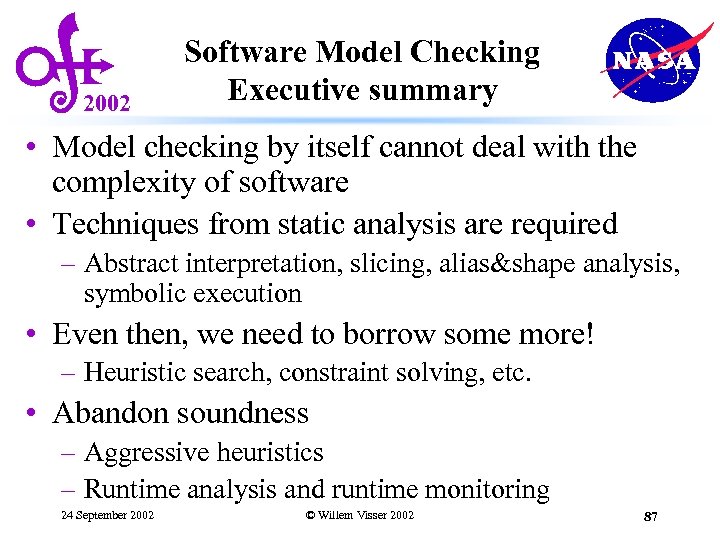

2002 Software Model Checking Executive summary • Model checking by itself cannot deal with the complexity of software • Techniques from static analysis are required – Abstract interpretation, slicing, alias&shape analysis, symbolic execution • Even then, we need to borrow some more! – Heuristic search, constraint solving, etc. • Abandon soundness – Aggressive heuristics – Runtime analysis and runtime monitoring 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 87

2002 Software Model Checking Executive summary • Model checking by itself cannot deal with the complexity of software • Techniques from static analysis are required – Abstract interpretation, slicing, alias&shape analysis, symbolic execution • Even then, we need to borrow some more! – Heuristic search, constraint solving, etc. • Abandon soundness – Aggressive heuristics – Runtime analysis and runtime monitoring 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 87

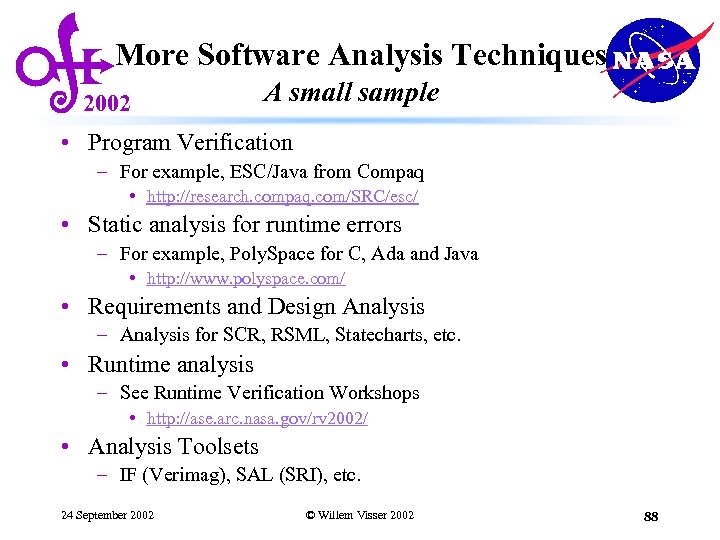

More Software Analysis Techniques 2002 A small sample • Program Verification – For example, ESC/Java from Compaq • http: //research. compaq. com/SRC/esc/ • Static analysis for runtime errors – For example, Poly. Space for C, Ada and Java • http: //www. polyspace. com/ • Requirements and Design Analysis – Analysis for SCR, RSML, Statecharts, etc. • Runtime analysis – See Runtime Verification Workshops • http: //ase. arc. nasa. gov/rv 2002/ • Analysis Toolsets – IF (Verimag), SAL (SRI), etc. 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 88

More Software Analysis Techniques 2002 A small sample • Program Verification – For example, ESC/Java from Compaq • http: //research. compaq. com/SRC/esc/ • Static analysis for runtime errors – For example, Poly. Space for C, Ada and Java • http: //www. polyspace. com/ • Requirements and Design Analysis – Analysis for SCR, RSML, Statecharts, etc. • Runtime analysis – See Runtime Verification Workshops • http: //ase. arc. nasa. gov/rv 2002/ • Analysis Toolsets – IF (Verimag), SAL (SRI), etc. 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 88

2002 Overview • Introduction to Model Checking • Program Model Checking • Case Studies – Remote Agent – DEOS – Mars Rover • Future of Software Model Checking 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 89

2002 Overview • Introduction to Model Checking • Program Model Checking • Case Studies – Remote Agent – DEOS – Mars Rover • Future of Software Model Checking 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 89

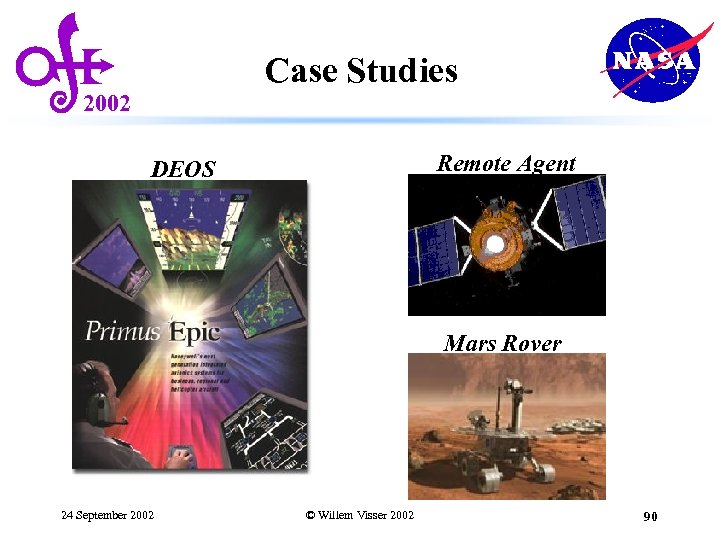

Case Studies 2002 Remote Agent DEOS Mars Rover 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 90

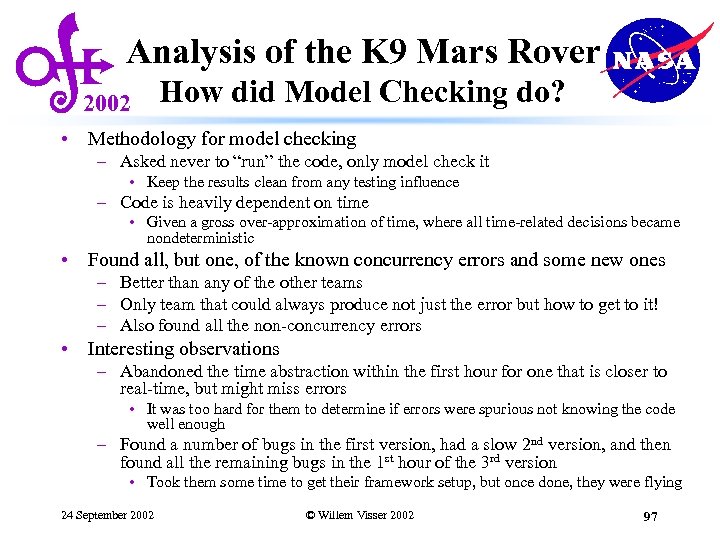

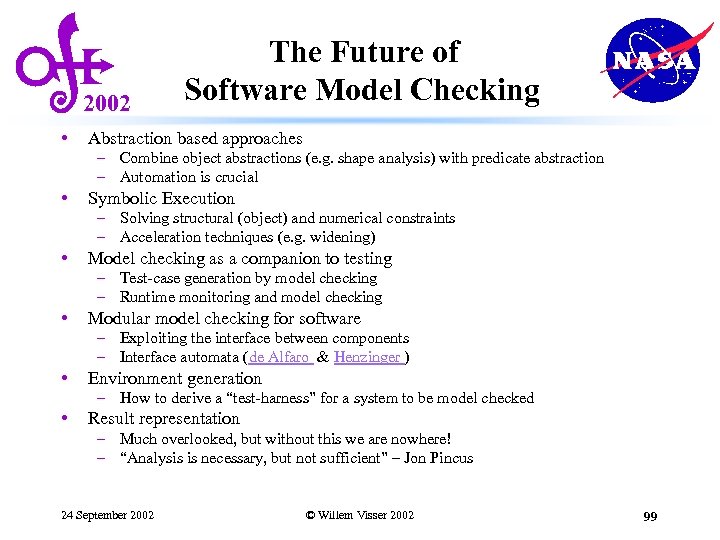

Case Studies 2002 Remote Agent DEOS Mars Rover 24 September 2002 © Willem Visser 2002 90