d9d1881e4e26bddc45e41233eb8c08c3.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 72

14 EXCHANGE RATES I: THE MONETARY APPROACH IN THE LONG RUN 1 Exchange Rates and Prices in the Long Run 2 Money, Prices, and Exchange Rates in the Long Run 3 The Monetary Approach 4 Money, Interest, and Prices in the Long Run 5 Monetary Regimes and Exchange Rate Regimes 6 Conclusions

14 EXCHANGE RATES I: THE MONETARY APPROACH IN THE LONG RUN 1 Exchange Rates and Prices in the Long Run 2 Money, Prices, and Exchange Rates in the Long Run 3 The Monetary Approach 4 Money, Interest, and Prices in the Long Run 5 Monetary Regimes and Exchange Rate Regimes 6 Conclusions

Introduction to Exchange Rates and Prices • Consider some hypothetical data on prices and exchange rates in the U. S. and U. K. : w Prices of U. S. and U. K. CPI baskets § 1970 PUK=£ 100 § 1970 PUS=$175 1990 PUK=£ 110 PUS=$175 1990 E£/$=0. 63 w Exchange rates (£/$) § 1970 E£/$=0. 57 w Prices of baskets in common currency (U. S. $) § UK § US 1970 $175 (= £ 100/ 0. 57) 1990 $175 (= £ 110/ 0. 63) $175 in both years • Is it coincidence that the exchange rate and price levels adjusted in this way? © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 2 of 93

Introduction to Exchange Rates and Prices • Consider some hypothetical data on prices and exchange rates in the U. S. and U. K. : w Prices of U. S. and U. K. CPI baskets § 1970 PUK=£ 100 § 1970 PUS=$175 1990 PUK=£ 110 PUS=$175 1990 E£/$=0. 63 w Exchange rates (£/$) § 1970 E£/$=0. 57 w Prices of baskets in common currency (U. S. $) § UK § US 1970 $175 (= £ 100/ 0. 57) 1990 $175 (= £ 110/ 0. 63) $175 in both years • Is it coincidence that the exchange rate and price levels adjusted in this way? © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 2 of 93

Introduction to Exchange Rates and Prices • The ideas of arbitrage w Chapter 13: applied there to currencies and interest rates w Chapter 14: applied here to the goods market • The prices of goods and services in different countries are related to the exchange rate. w When the relative prices of goods changes, the exchange rate adjusts to reflect this change (but this may take time). • The monetary approach to exchange rates is the result. w A long run theory linking money, exchange rates, prices, and interest rates. • The foundation of this theory is the fundamental arbitrage principle known as the law of one price. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 3 of 93

Introduction to Exchange Rates and Prices • The ideas of arbitrage w Chapter 13: applied there to currencies and interest rates w Chapter 14: applied here to the goods market • The prices of goods and services in different countries are related to the exchange rate. w When the relative prices of goods changes, the exchange rate adjusts to reflect this change (but this may take time). • The monetary approach to exchange rates is the result. w A long run theory linking money, exchange rates, prices, and interest rates. • The foundation of this theory is the fundamental arbitrage principle known as the law of one price. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 3 of 93

The Law of One Price • Key assumption – frictionless trade w w No transaction costs No barriers to trade Identical goods in each location No barriers to price adjustment • General idea: w Prices must be equal in all locations for any good when expressed in a common currency. w Otherwise, there would be a profit opportunity from buying low and selling high. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 4 of 93

The Law of One Price • Key assumption – frictionless trade w w No transaction costs No barriers to trade Identical goods in each location No barriers to price adjustment • General idea: w Prices must be equal in all locations for any good when expressed in a common currency. w Otherwise, there would be a profit opportunity from buying low and selling high. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 4 of 93

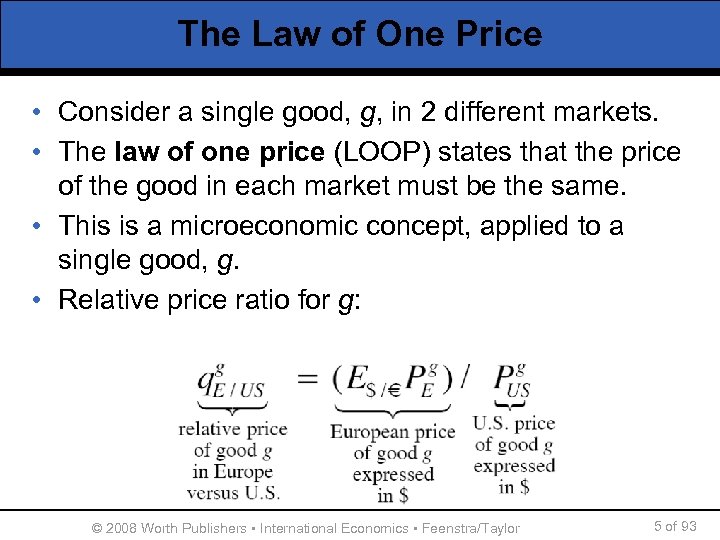

The Law of One Price • Consider a single good, g, in 2 different markets. • The law of one price (LOOP) states that the price of the good in each market must be the same. • This is a microeconomic concept, applied to a single good, g. • Relative price ratio for g: © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 5 of 93

The Law of One Price • Consider a single good, g, in 2 different markets. • The law of one price (LOOP) states that the price of the good in each market must be the same. • This is a microeconomic concept, applied to a single good, g. • Relative price ratio for g: © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 5 of 93

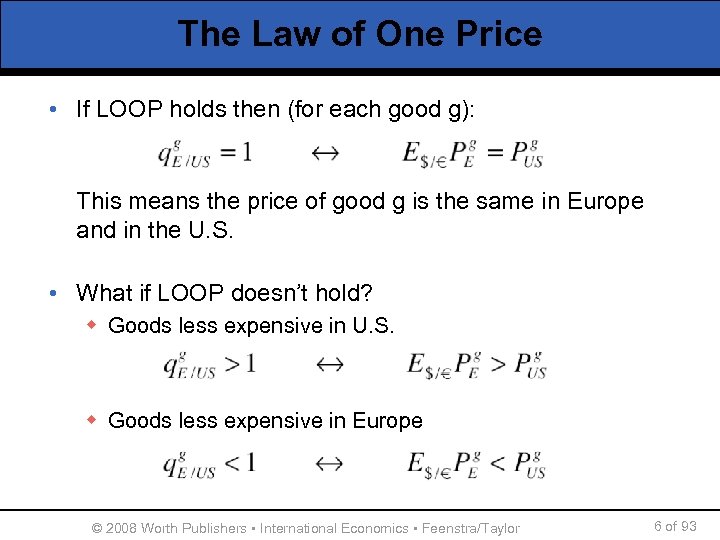

The Law of One Price • If LOOP holds then (for each good g): This means the price of good g is the same in Europe and in the U. S. • What if LOOP doesn’t hold? w Goods less expensive in U. S. w Goods less expensive in Europe © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 6 of 93

The Law of One Price • If LOOP holds then (for each good g): This means the price of good g is the same in Europe and in the U. S. • What if LOOP doesn’t hold? w Goods less expensive in U. S. w Goods less expensive in Europe © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 6 of 93

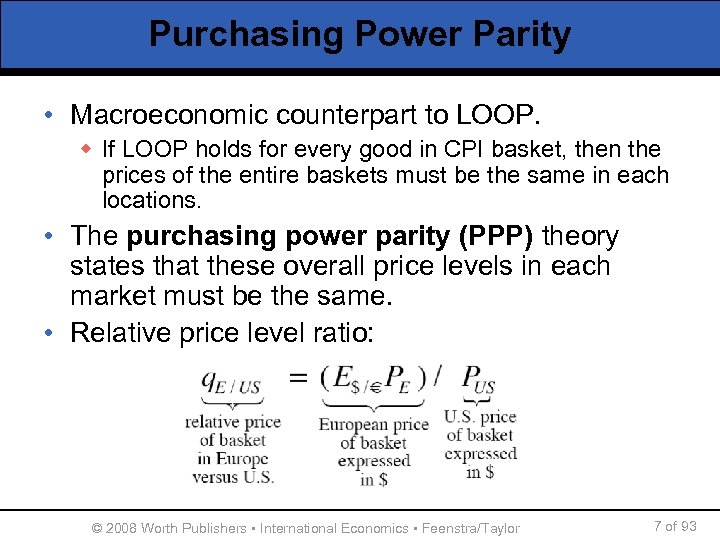

Purchasing Power Parity • Macroeconomic counterpart to LOOP. w If LOOP holds for every good in CPI basket, then the prices of the entire baskets must be the same in each locations. • The purchasing power parity (PPP) theory states that these overall price levels in each market must be the same. • Relative price level ratio: © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 7 of 93

Purchasing Power Parity • Macroeconomic counterpart to LOOP. w If LOOP holds for every good in CPI basket, then the prices of the entire baskets must be the same in each locations. • The purchasing power parity (PPP) theory states that these overall price levels in each market must be the same. • Relative price level ratio: © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 7 of 93

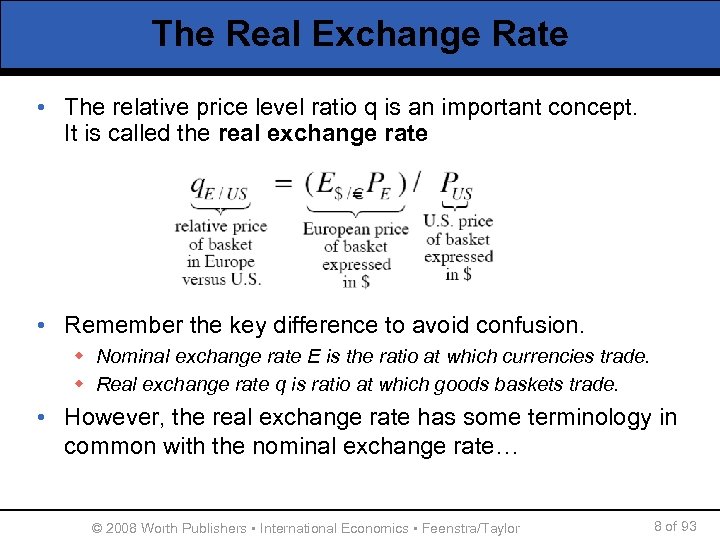

The Real Exchange Rate • The relative price level ratio q is an important concept. It is called the real exchange rate • Remember the key difference to avoid confusion. w Nominal exchange rate E is the ratio at which currencies trade. w Real exchange rate q is ratio at which goods baskets trade. • However, the real exchange rate has some terminology in common with the nominal exchange rate… © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 8 of 93

The Real Exchange Rate • The relative price level ratio q is an important concept. It is called the real exchange rate • Remember the key difference to avoid confusion. w Nominal exchange rate E is the ratio at which currencies trade. w Real exchange rate q is ratio at which goods baskets trade. • However, the real exchange rate has some terminology in common with the nominal exchange rate… © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 8 of 93

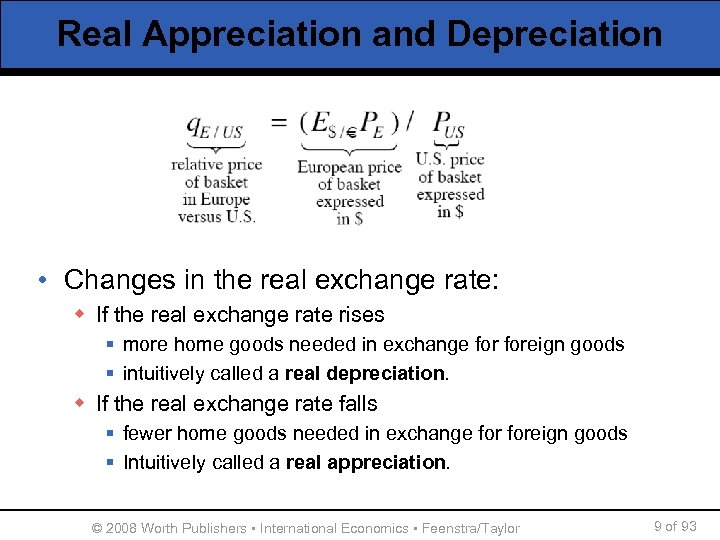

Real Appreciation and Depreciation • Changes in the real exchange rate: w If the real exchange rate rises § more home goods needed in exchange foreign goods § intuitively called a real depreciation. w If the real exchange rate falls § fewer home goods needed in exchange foreign goods § Intuitively called a real appreciation. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 9 of 93

Real Appreciation and Depreciation • Changes in the real exchange rate: w If the real exchange rate rises § more home goods needed in exchange foreign goods § intuitively called a real depreciation. w If the real exchange rate falls § fewer home goods needed in exchange foreign goods § Intuitively called a real appreciation. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 9 of 93

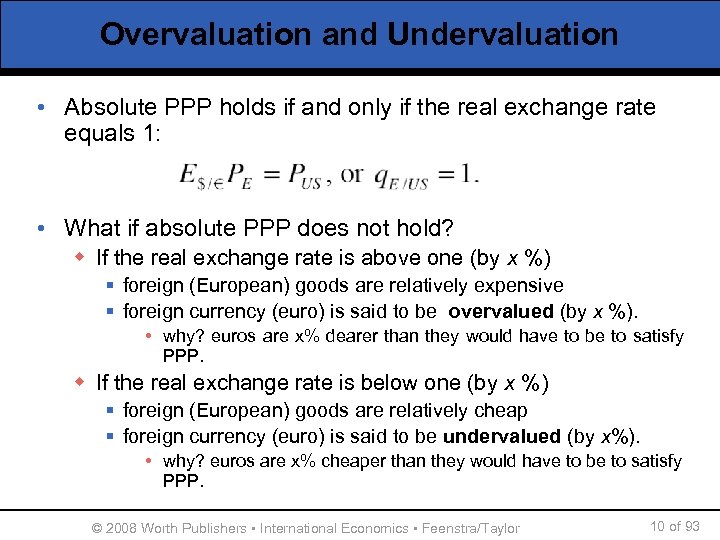

Overvaluation and Undervaluation • Absolute PPP holds if and only if the real exchange rate equals 1: • What if absolute PPP does not hold? w If the real exchange rate is above one (by x %) § foreign (European) goods are relatively expensive § foreign currency (euro) is said to be overvalued (by x %). • why? euros are x% dearer than they would have to be to satisfy PPP. w If the real exchange rate is below one (by x %) § foreign (European) goods are relatively cheap § foreign currency (euro) is said to be undervalued (by x%). • why? euros are x% cheaper than they would have to be to satisfy PPP. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 10 of 93

Overvaluation and Undervaluation • Absolute PPP holds if and only if the real exchange rate equals 1: • What if absolute PPP does not hold? w If the real exchange rate is above one (by x %) § foreign (European) goods are relatively expensive § foreign currency (euro) is said to be overvalued (by x %). • why? euros are x% dearer than they would have to be to satisfy PPP. w If the real exchange rate is below one (by x %) § foreign (European) goods are relatively cheap § foreign currency (euro) is said to be undervalued (by x%). • why? euros are x% cheaper than they would have to be to satisfy PPP. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 10 of 93

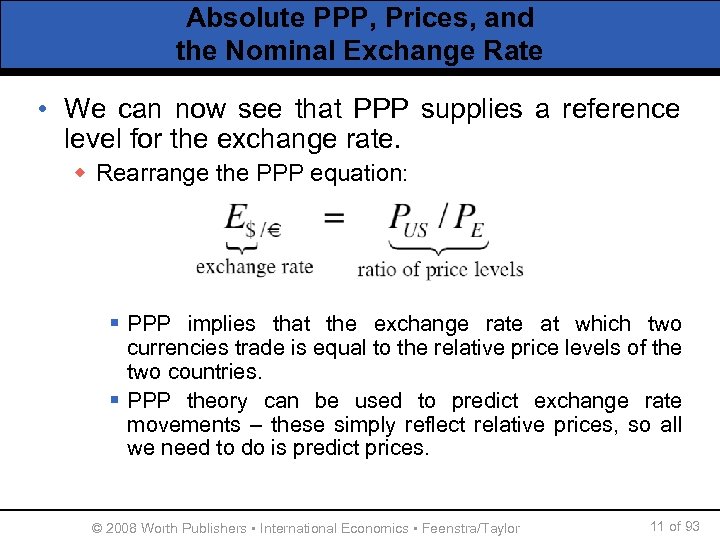

Absolute PPP, Prices, and the Nominal Exchange Rate • We can now see that PPP supplies a reference level for the exchange rate. w Rearrange the PPP equation: § PPP implies that the exchange rate at which two currencies trade is equal to the relative price levels of the two countries. § PPP theory can be used to predict exchange rate movements – these simply reflect relative prices, so all we need to do is predict prices. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 11 of 93

Absolute PPP, Prices, and the Nominal Exchange Rate • We can now see that PPP supplies a reference level for the exchange rate. w Rearrange the PPP equation: § PPP implies that the exchange rate at which two currencies trade is equal to the relative price levels of the two countries. § PPP theory can be used to predict exchange rate movements – these simply reflect relative prices, so all we need to do is predict prices. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 11 of 93

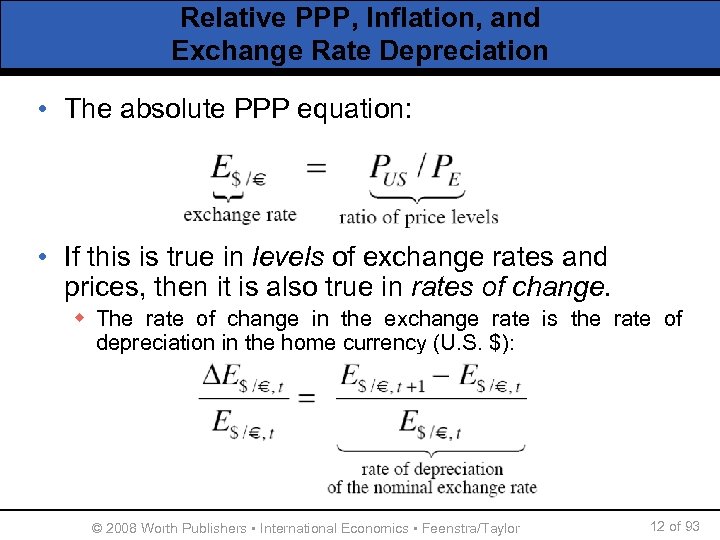

Relative PPP, Inflation, and Exchange Rate Depreciation • The absolute PPP equation: • If this is true in levels of exchange rates and prices, then it is also true in rates of change. w The rate of change in the exchange rate is the rate of depreciation in the home currency (U. S. $): © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 12 of 93

Relative PPP, Inflation, and Exchange Rate Depreciation • The absolute PPP equation: • If this is true in levels of exchange rates and prices, then it is also true in rates of change. w The rate of change in the exchange rate is the rate of depreciation in the home currency (U. S. $): © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 12 of 93

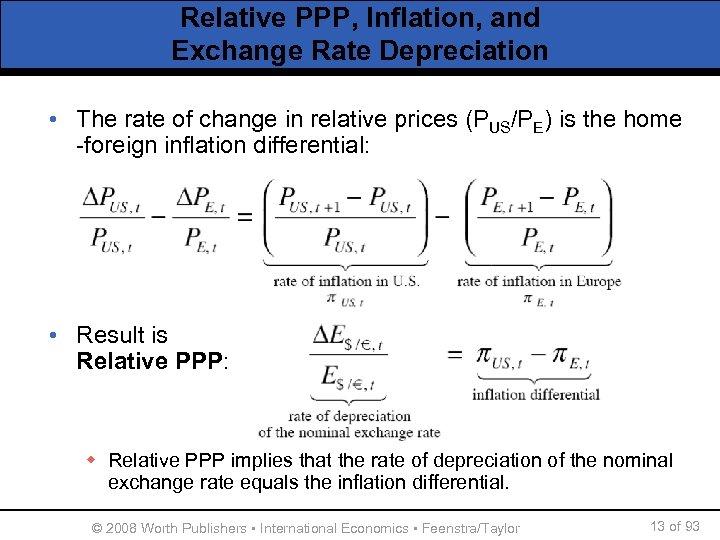

Relative PPP, Inflation, and Exchange Rate Depreciation • The rate of change in relative prices (PUS/PE) is the home -foreign inflation differential: • Result is Relative PPP: w Relative PPP implies that the rate of depreciation of the nominal exchange rate equals the inflation differential. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 13 of 93

Relative PPP, Inflation, and Exchange Rate Depreciation • The rate of change in relative prices (PUS/PE) is the home -foreign inflation differential: • Result is Relative PPP: w Relative PPP implies that the rate of depreciation of the nominal exchange rate equals the inflation differential. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 13 of 93

Relative PPP, Inflation, and Exchange Rate Depreciation • Relative PPP is derived from Absolute PPP w If Absolute PPP holds then Relative PPP must hold also. • But the converse need not be true: one could imagine a case where a basket always costs a fixed amount more, say, 10% in common currency terms in one country than the other: w In this case Absolute PPP fails, but Relative PPP holds. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 14 of 93

Relative PPP, Inflation, and Exchange Rate Depreciation • Relative PPP is derived from Absolute PPP w If Absolute PPP holds then Relative PPP must hold also. • But the converse need not be true: one could imagine a case where a basket always costs a fixed amount more, say, 10% in common currency terms in one country than the other: w In this case Absolute PPP fails, but Relative PPP holds. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 14 of 93

Where Are We Now? • The PPP theory, whether in absolute of relative form, suggests that price levels in different countries and exchange rates are tightly linked, either in levels or in rates of change. • Stop and ask some questions: w Where do price levels come from? w Do the data support theory of purchasing power parity? © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 15 of 93

Where Are We Now? • The PPP theory, whether in absolute of relative form, suggests that price levels in different countries and exchange rates are tightly linked, either in levels or in rates of change. • Stop and ask some questions: w Where do price levels come from? w Do the data support theory of purchasing power parity? © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 15 of 93

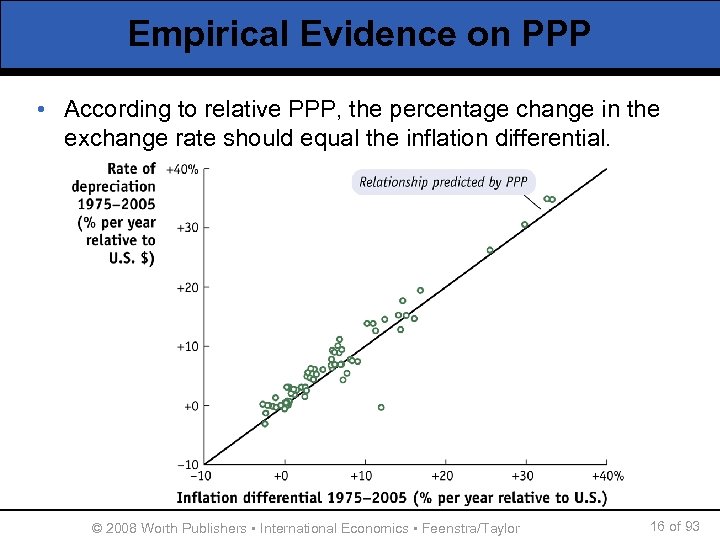

Empirical Evidence on PPP • According to relative PPP, the percentage change in the exchange rate should equal the inflation differential. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 16 of 93

Empirical Evidence on PPP • According to relative PPP, the percentage change in the exchange rate should equal the inflation differential. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 16 of 93

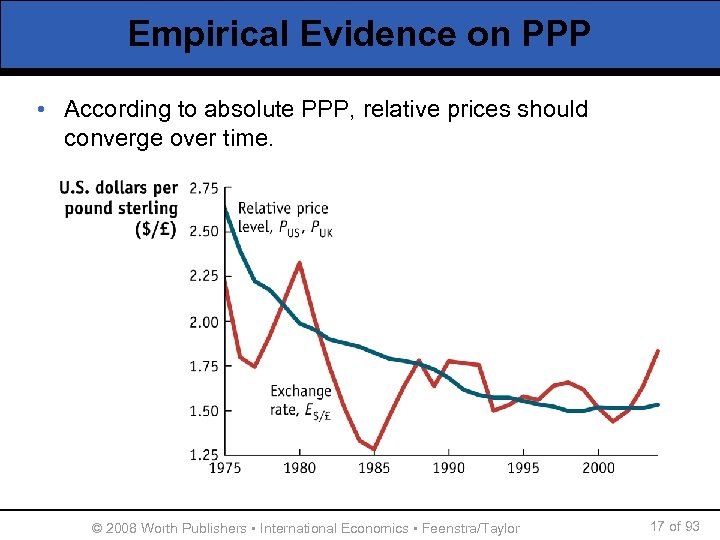

Empirical Evidence on PPP • According to absolute PPP, relative prices should converge over time. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 17 of 93

Empirical Evidence on PPP • According to absolute PPP, relative prices should converge over time. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 17 of 93

How Slow is Convergence to PPP? • Two measures: w Speed of convergence: how quickly deviations from PPP disappear over time (estimated to be 15% per year). w Half-life: how long it takes for half of the deviations from PPP to disappear (estimated to be about four years). • These estimates are useful forecasting how long exchange rate adjustments will take. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 18 of 93

How Slow is Convergence to PPP? • Two measures: w Speed of convergence: how quickly deviations from PPP disappear over time (estimated to be 15% per year). w Half-life: how long it takes for half of the deviations from PPP to disappear (estimated to be about four years). • These estimates are useful forecasting how long exchange rate adjustments will take. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 18 of 93

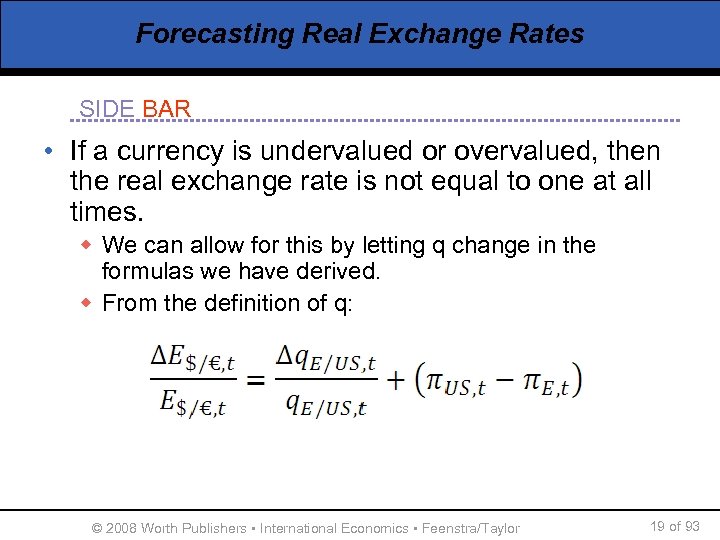

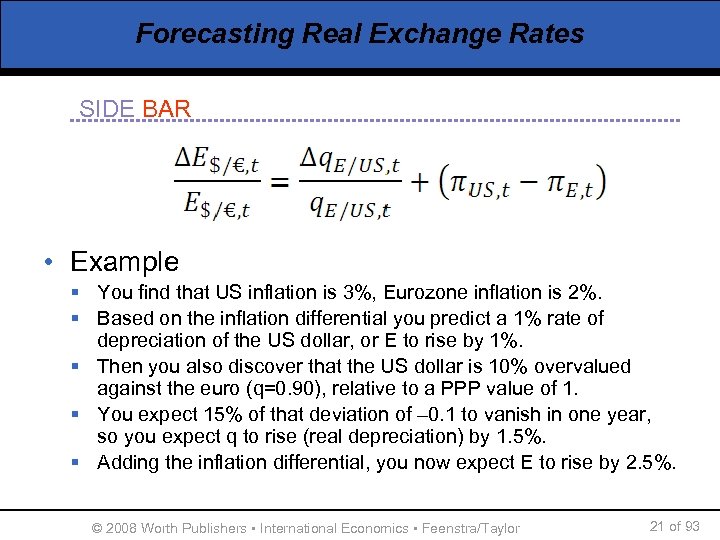

Forecasting Real Exchange Rates SIDE BAR • If a currency is undervalued or overvalued, then the real exchange rate is not equal to one at all times. w We can allow for this by letting q change in the formulas we have derived. w From the definition of q: © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 19 of 93

Forecasting Real Exchange Rates SIDE BAR • If a currency is undervalued or overvalued, then the real exchange rate is not equal to one at all times. w We can allow for this by letting q change in the formulas we have derived. w From the definition of q: © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 19 of 93

Forecasting Real Exchange Rates SIDE BAR • If q=1 is constant (PPP) then the 1 st term on the right is zero. • To forecast the change in E you just need to forecast the inflation differential, as before. • If q deviates from 1, and we can measure it, then we can use the convergence speed to estimate how quickly q will rise/fall towards 1. • This estimate of the rate of change of q can then be factored in, in addition to the inflation differential, to allow for an estimate of nominal depreciation. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 20 of 93

Forecasting Real Exchange Rates SIDE BAR • If q=1 is constant (PPP) then the 1 st term on the right is zero. • To forecast the change in E you just need to forecast the inflation differential, as before. • If q deviates from 1, and we can measure it, then we can use the convergence speed to estimate how quickly q will rise/fall towards 1. • This estimate of the rate of change of q can then be factored in, in addition to the inflation differential, to allow for an estimate of nominal depreciation. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 20 of 93

Forecasting Real Exchange Rates SIDE BAR • Example § You find that US inflation is 3%, Eurozone inflation is 2%. § Based on the inflation differential you predict a 1% rate of depreciation of the US dollar, or E to rise by 1%. § Then you also discover that the US dollar is 10% overvalued against the euro (q=0. 90), relative to a PPP value of 1. § You expect 15% of that deviation of – 0. 1 to vanish in one year, so you expect q to rise (real depreciation) by 1. 5%. § Adding the inflation differential, you now expect E to rise by 2. 5%. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 21 of 93

Forecasting Real Exchange Rates SIDE BAR • Example § You find that US inflation is 3%, Eurozone inflation is 2%. § Based on the inflation differential you predict a 1% rate of depreciation of the US dollar, or E to rise by 1%. § Then you also discover that the US dollar is 10% overvalued against the euro (q=0. 90), relative to a PPP value of 1. § You expect 15% of that deviation of – 0. 1 to vanish in one year, so you expect q to rise (real depreciation) by 1. 5%. § Adding the inflation differential, you now expect E to rise by 2. 5%. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 21 of 93

What Explains Deviations from PPP? • Transaction costs w Recent estimates suggest transportation costs may add about 20% to the cost of goods moving internationally. w Tariffs (and other policy barriers) may add another 10%, with variation across goods and across countries. w Further costs arise due to the time taken to ship goods. • Nontraded goods w Some goods are inherently nontradable; w Most goods fall somewhere in between freely tradable and purely nontradable. § For example: a cup of coffee in a café. It includes some highly-traded components (coffee beans, sugar) and some nontraded components (the labor input of the barista). © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 22 of 93

What Explains Deviations from PPP? • Transaction costs w Recent estimates suggest transportation costs may add about 20% to the cost of goods moving internationally. w Tariffs (and other policy barriers) may add another 10%, with variation across goods and across countries. w Further costs arise due to the time taken to ship goods. • Nontraded goods w Some goods are inherently nontradable; w Most goods fall somewhere in between freely tradable and purely nontradable. § For example: a cup of coffee in a café. It includes some highly-traded components (coffee beans, sugar) and some nontraded components (the labor input of the barista). © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 22 of 93

What Explains Deviations from PPP? • Imperfect competition and legal obstacles w Many goods are differentiated products, often with brand names, copyrights, and legal protection. w Firms can engage in price discrimination across countries, using legal protection to prevent arbitrage § E. g. , if you try to import large quantities of a pharmaceuticals, and resell them, you may hear from the firm’s lawyers. • Price stickiness w One of the most common assumptions of macroeconomics is that prices are “sticky” prices in the short run. w PPP assumes that arbitrage can force prices to adjust, but adjustment will be slowed down by price stickiness. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 23 of 93

What Explains Deviations from PPP? • Imperfect competition and legal obstacles w Many goods are differentiated products, often with brand names, copyrights, and legal protection. w Firms can engage in price discrimination across countries, using legal protection to prevent arbitrage § E. g. , if you try to import large quantities of a pharmaceuticals, and resell them, you may hear from the firm’s lawyers. • Price stickiness w One of the most common assumptions of macroeconomics is that prices are “sticky” prices in the short run. w PPP assumes that arbitrage can force prices to adjust, but adjustment will be slowed down by price stickiness. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 23 of 93

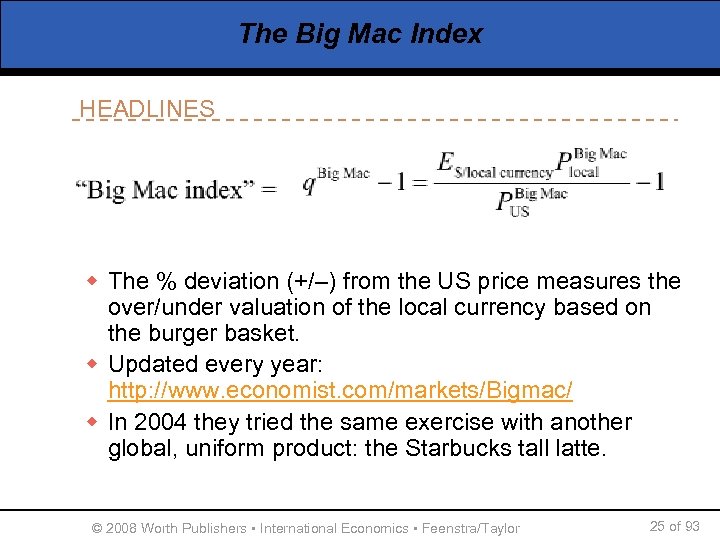

The Big Mac Index HEADLINES • For over 20 years The Economist newspaper has used PPP to evaluate whether currencies are undervalued or overvalued. w Recall, home currency is x% overvalued/undervalued when the home basket costs x% more/less than the foreign basket. • The test is really based on Law of One Price because it relies on a basket with one good. w Invented (1986) by economics editor Pam Woodall. She asked correspondents around the world to visit Mc. Donalds and get prices of a Big Mac, then compute price relative to the U. S. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 24 of 93

The Big Mac Index HEADLINES • For over 20 years The Economist newspaper has used PPP to evaluate whether currencies are undervalued or overvalued. w Recall, home currency is x% overvalued/undervalued when the home basket costs x% more/less than the foreign basket. • The test is really based on Law of One Price because it relies on a basket with one good. w Invented (1986) by economics editor Pam Woodall. She asked correspondents around the world to visit Mc. Donalds and get prices of a Big Mac, then compute price relative to the U. S. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 24 of 93

The Big Mac Index HEADLINES w The % deviation (+/–) from the US price measures the over/under valuation of the local currency based on the burger basket. w Updated every year: http: //www. economist. com/markets/Bigmac/ w In 2004 they tried the same exercise with another global, uniform product: the Starbucks tall latte. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 25 of 93

The Big Mac Index HEADLINES w The % deviation (+/–) from the US price measures the over/under valuation of the local currency based on the burger basket. w Updated every year: http: //www. economist. com/markets/Bigmac/ w In 2004 they tried the same exercise with another global, uniform product: the Starbucks tall latte. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 25 of 93

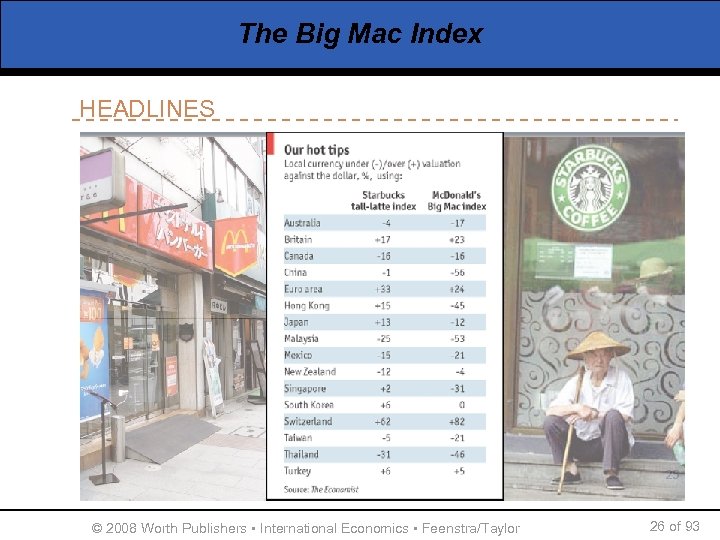

The Big Mac Index HEADLINES © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 26 of 93

The Big Mac Index HEADLINES © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 26 of 93

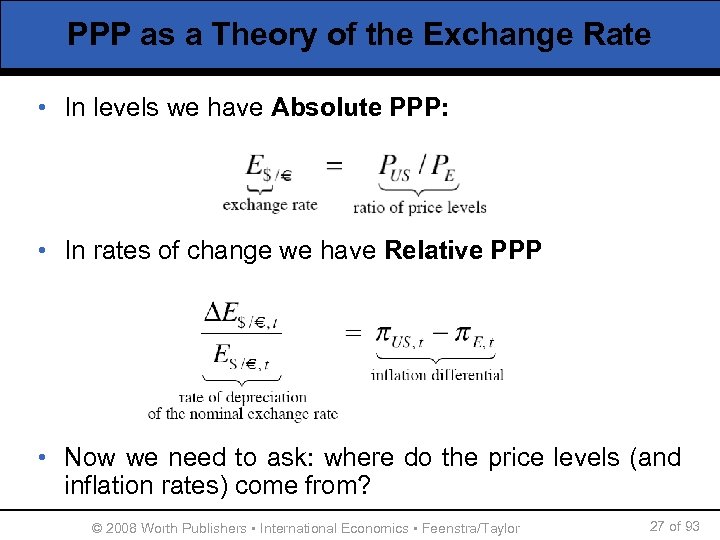

PPP as a Theory of the Exchange Rate • In levels we have Absolute PPP: • In rates of change we have Relative PPP • Now we need to ask: where do the price levels (and inflation rates) come from? © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 27 of 93

PPP as a Theory of the Exchange Rate • In levels we have Absolute PPP: • In rates of change we have Relative PPP • Now we need to ask: where do the price levels (and inflation rates) come from? © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 27 of 93

What Is Money? • Money is an object that serves three functions: w Store of value § Money is an asset that can be used to buy goods in the future. § Financial assets (stocks and bonds) and property are other stores of value that are not money. w Unit of account § How prices are expressed. § A unit of account is used to measure value of different items. w Medium of exchange § Money is generally accepted as a means of payment for goods. § Money is the most liquid form of payment: an asset that is easily converted into goods and services © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 28 of 93

What Is Money? • Money is an object that serves three functions: w Store of value § Money is an asset that can be used to buy goods in the future. § Financial assets (stocks and bonds) and property are other stores of value that are not money. w Unit of account § How prices are expressed. § A unit of account is used to measure value of different items. w Medium of exchange § Money is generally accepted as a means of payment for goods. § Money is the most liquid form of payment: an asset that is easily converted into goods and services © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 28 of 93

Measurement of Money • Different measures of money w Monetary base = Currency § Currency in circulation plus currency in banking system w M 1 = Currency in circulation + demand deposits § Demand deposits are checking accounts payable on demand by the bank customer. w M 2 = M 1 + other less liquid assets § Other less liquid assets include savings accounts, small time deposits, and money market mutual funds. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 29 of 93

Measurement of Money • Different measures of money w Monetary base = Currency § Currency in circulation plus currency in banking system w M 1 = Currency in circulation + demand deposits § Demand deposits are checking accounts payable on demand by the bank customer. w M 2 = M 1 + other less liquid assets § Other less liquid assets include savings accounts, small time deposits, and money market mutual funds. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 29 of 93

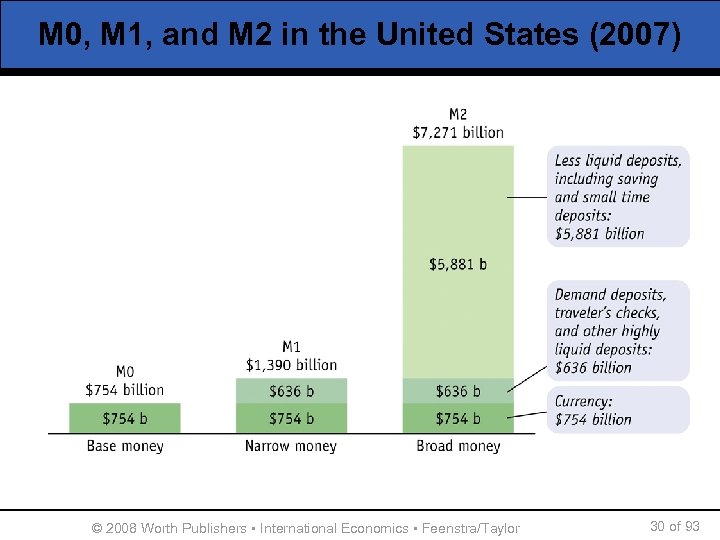

M 0, M 1, and M 2 in the United States (2007) © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 30 of 93

M 0, M 1, and M 2 in the United States (2007) © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 30 of 93

The Supply of Money • We will focus on M 1, the predominant type of money that we use for transactions. • We will assume that the nominal money supply M = M 1 is controlled by the central bank. w In fact, the central bank directly controls only part of M, namely the monetary base (M 0). w However, central banks can indirectly control M 1 by using interest rate policies and other tools (such as reserve requirements) to influence the total amount of bank deposits created (M 1 – M 0). © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 31 of 93

The Supply of Money • We will focus on M 1, the predominant type of money that we use for transactions. • We will assume that the nominal money supply M = M 1 is controlled by the central bank. w In fact, the central bank directly controls only part of M, namely the monetary base (M 0). w However, central banks can indirectly control M 1 by using interest rate policies and other tools (such as reserve requirements) to influence the total amount of bank deposits created (M 1 – M 0). © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 31 of 93

The Demand for Money: A Simple Model • We assume that the demand for nominal money is driven by the need to use money to undertake transactions. • In the simplest model, the quantity theory: the amount of transactions assumed to be proportional to the dollar value of nominal income PY (where real income is Y). © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 32 of 93

The Demand for Money: A Simple Model • We assume that the demand for nominal money is driven by the need to use money to undertake transactions. • In the simplest model, the quantity theory: the amount of transactions assumed to be proportional to the dollar value of nominal income PY (where real income is Y). © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 32 of 93

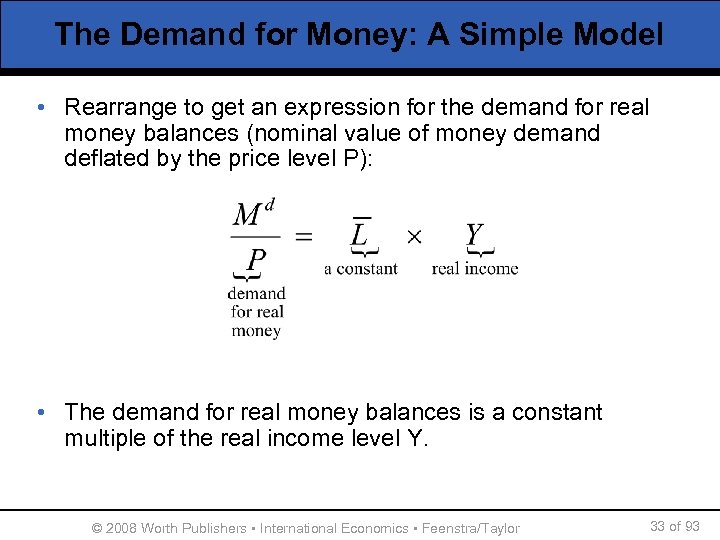

The Demand for Money: A Simple Model • Rearrange to get an expression for the demand for real money balances (nominal value of money demand deflated by the price level P): • The demand for real money balances is a constant multiple of the real income level Y. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 33 of 93

The Demand for Money: A Simple Model • Rearrange to get an expression for the demand for real money balances (nominal value of money demand deflated by the price level P): • The demand for real money balances is a constant multiple of the real income level Y. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 33 of 93

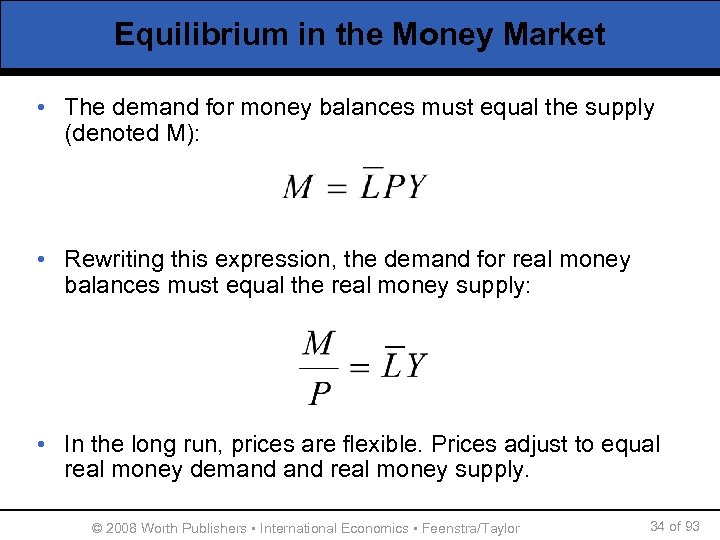

Equilibrium in the Money Market • The demand for money balances must equal the supply (denoted M): • Rewriting this expression, the demand for real money balances must equal the real money supply: • In the long run, prices are flexible. Prices adjust to equal real money demand real money supply. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 34 of 93

Equilibrium in the Money Market • The demand for money balances must equal the supply (denoted M): • Rewriting this expression, the demand for real money balances must equal the real money supply: • In the long run, prices are flexible. Prices adjust to equal real money demand real money supply. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 34 of 93

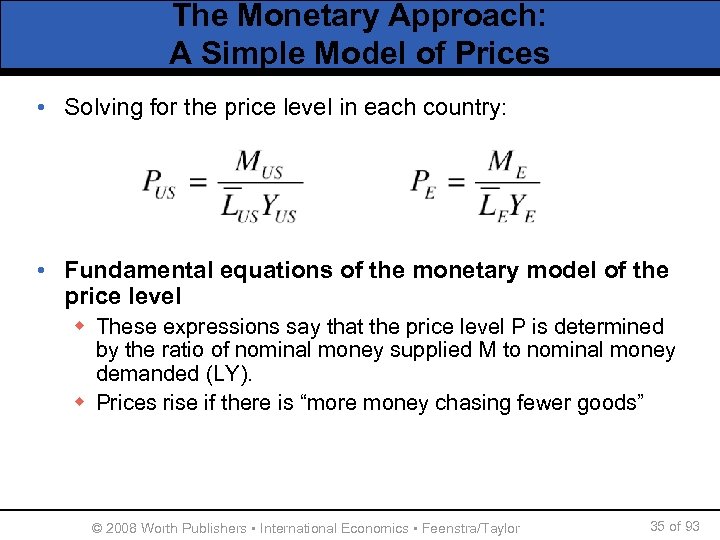

The Monetary Approach: A Simple Model of Prices • Solving for the price level in each country: • Fundamental equations of the monetary model of the price level w These expressions say that the price level P is determined by the ratio of nominal money supplied M to nominal money demanded (LY). w Prices rise if there is “more money chasing fewer goods” © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 35 of 93

The Monetary Approach: A Simple Model of Prices • Solving for the price level in each country: • Fundamental equations of the monetary model of the price level w These expressions say that the price level P is determined by the ratio of nominal money supplied M to nominal money demanded (LY). w Prices rise if there is “more money chasing fewer goods” © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 35 of 93

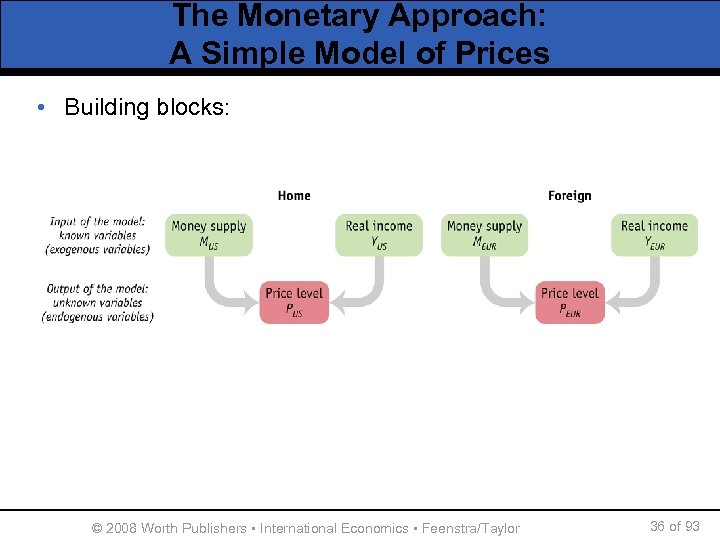

The Monetary Approach: A Simple Model of Prices • Building blocks: © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 36 of 93

The Monetary Approach: A Simple Model of Prices • Building blocks: © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 36 of 93

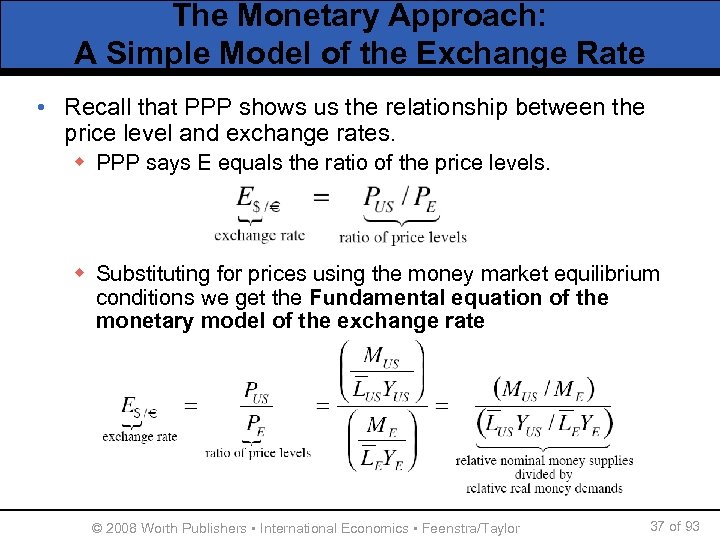

The Monetary Approach: A Simple Model of the Exchange Rate • Recall that PPP shows us the relationship between the price level and exchange rates. w PPP says E equals the ratio of the price levels. w Substituting for prices using the money market equilibrium conditions we get the Fundamental equation of the monetary model of the exchange rate © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 37 of 93

The Monetary Approach: A Simple Model of the Exchange Rate • Recall that PPP shows us the relationship between the price level and exchange rates. w PPP says E equals the ratio of the price levels. w Substituting for prices using the money market equilibrium conditions we get the Fundamental equation of the monetary model of the exchange rate © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 37 of 93

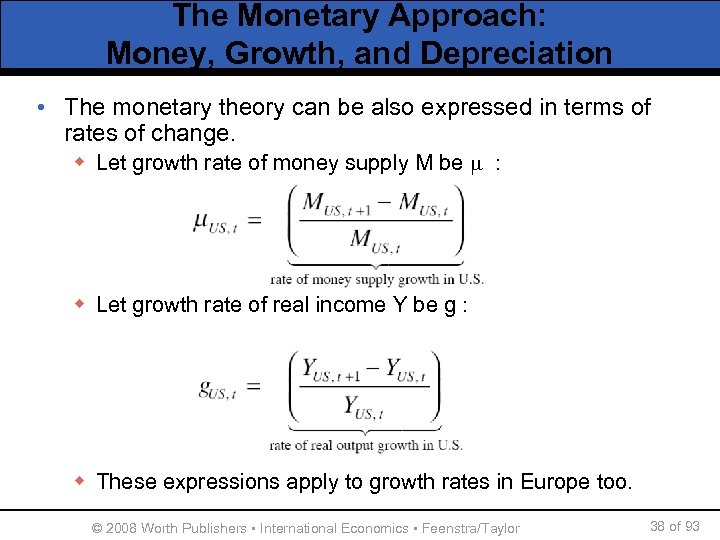

The Monetary Approach: Money, Growth, and Depreciation • The monetary theory can be also expressed in terms of rates of change. w Let growth rate of money supply M be m : w Let growth rate of real income Y be g : w These expressions apply to growth rates in Europe too. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 38 of 93

The Monetary Approach: Money, Growth, and Depreciation • The monetary theory can be also expressed in terms of rates of change. w Let growth rate of money supply M be m : w Let growth rate of real income Y be g : w These expressions apply to growth rates in Europe too. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 38 of 93

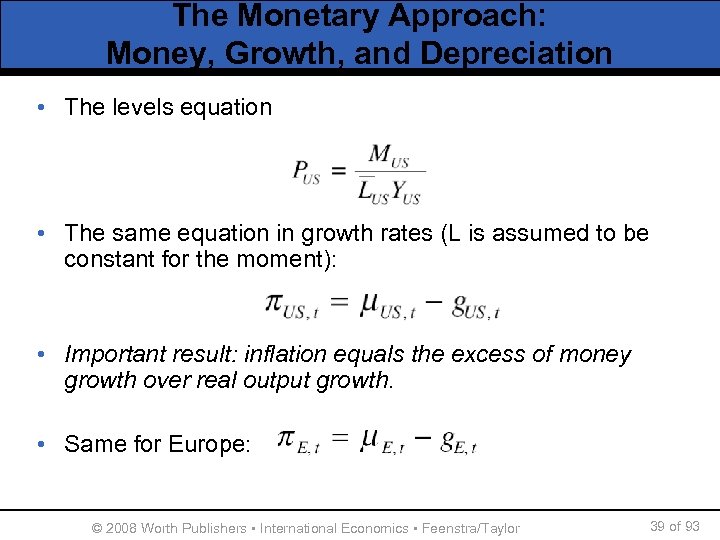

The Monetary Approach: Money, Growth, and Depreciation • The levels equation • The same equation in growth rates (L is assumed to be constant for the moment): • Important result: inflation equals the excess of money growth over real output growth. • Same for Europe: © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 39 of 93

The Monetary Approach: Money, Growth, and Depreciation • The levels equation • The same equation in growth rates (L is assumed to be constant for the moment): • Important result: inflation equals the excess of money growth over real output growth. • Same for Europe: © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 39 of 93

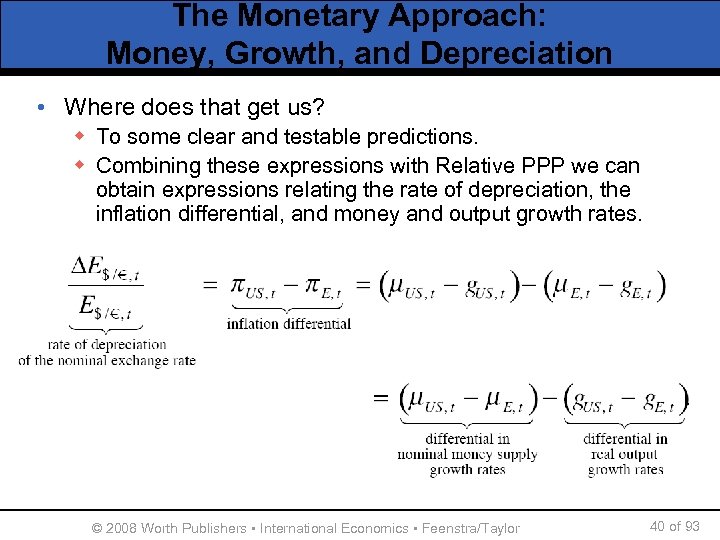

The Monetary Approach: Money, Growth, and Depreciation • Where does that get us? w To some clear and testable predictions. w Combining these expressions with Relative PPP we can obtain expressions relating the rate of depreciation, the inflation differential, and money and output growth rates. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 40 of 93

The Monetary Approach: Money, Growth, and Depreciation • Where does that get us? w To some clear and testable predictions. w Combining these expressions with Relative PPP we can obtain expressions relating the rate of depreciation, the inflation differential, and money and output growth rates. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 40 of 93

Exchange Rate Forecasts Using the Simple Model • Assumptions in a simple policy experiment w Both countries § Constant money growth rate m , fixed level of output Y w Foreign § Money growth m is zero, inflation p is zero • Consider two cases: w Case 1: Home money growth m is zero, inflation p is zero. Home implements a one-time x% increase in M. w Case 2: Home money growth m is positive, inflation p is positive. Home increases its rate of money growth m by D m • What happens to key economic variables according to the monetary approach in each case? © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 41 of 93

Exchange Rate Forecasts Using the Simple Model • Assumptions in a simple policy experiment w Both countries § Constant money growth rate m , fixed level of output Y w Foreign § Money growth m is zero, inflation p is zero • Consider two cases: w Case 1: Home money growth m is zero, inflation p is zero. Home implements a one-time x% increase in M. w Case 2: Home money growth m is positive, inflation p is positive. Home increases its rate of money growth m by D m • What happens to key economic variables according to the monetary approach in each case? © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 41 of 93

Exchange Rate Forecasts Using the Simple Model • Case 1: One-time x% increase in money supply M w w Real money balances remain unchanged (Y fixed). The home price level P increases by x%. The exchange rate E increases by x%. Result: a one-time jump of x % in all nominal variables. • Case 2: Home increases rate of money growth m by D m w We discuss this case first using a diagram… © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 42 of 93

Exchange Rate Forecasts Using the Simple Model • Case 1: One-time x% increase in money supply M w w Real money balances remain unchanged (Y fixed). The home price level P increases by x%. The exchange rate E increases by x%. Result: a one-time jump of x % in all nominal variables. • Case 2: Home increases rate of money growth m by D m w We discuss this case first using a diagram… © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 42 of 93

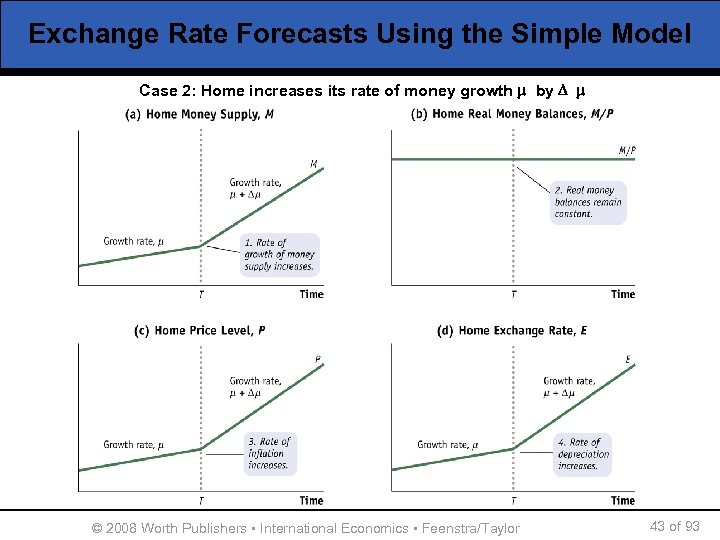

Exchange Rate Forecasts Using the Simple Model Case 2: Home increases its rate of money growth by © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 43 of 93

Exchange Rate Forecasts Using the Simple Model Case 2: Home increases its rate of money growth by © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 43 of 93

Exchange Rate Forecasts Using the Simple Model • Case 2: Home increases rate of money growth m by D m • Before the change: w M, P and E were all growing at rate m • After the change: w Real money balances M/P remain unchanged (Y fixed). w The home inflation rate increases by D m w The rate of exchange rate depreciation increases by D m percentage points. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 44 of 93

Exchange Rate Forecasts Using the Simple Model • Case 2: Home increases rate of money growth m by D m • Before the change: w M, P and E were all growing at rate m • After the change: w Real money balances M/P remain unchanged (Y fixed). w The home inflation rate increases by D m w The rate of exchange rate depreciation increases by D m percentage points. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 44 of 93

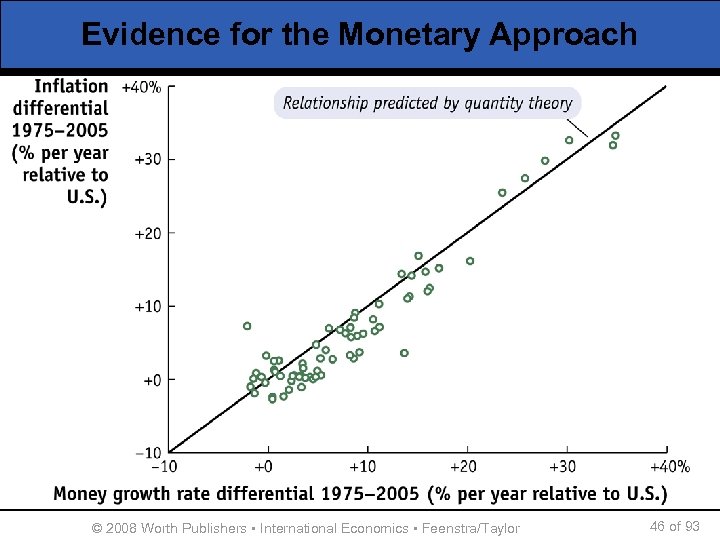

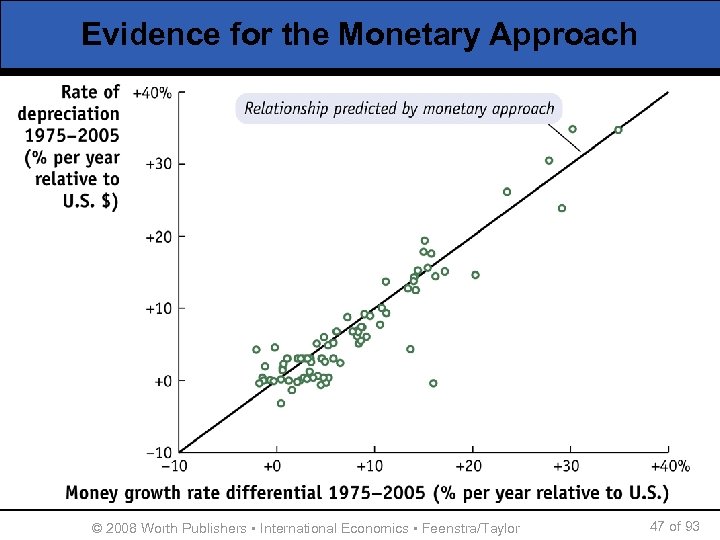

Evidence for the Monetary Approach • Two tests: • Test 1: Any change in the money growth rate differential should be reflected one-for-one with a change in the inflation differential. • Test 2: Differentials in money growth rates should reflect changes in the exchange rate. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 45 of 93

Evidence for the Monetary Approach • Two tests: • Test 1: Any change in the money growth rate differential should be reflected one-for-one with a change in the inflation differential. • Test 2: Differentials in money growth rates should reflect changes in the exchange rate. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 45 of 93

Evidence for the Monetary Approach © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 46 of 93

Evidence for the Monetary Approach © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 46 of 93

Evidence for the Monetary Approach © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 47 of 93

Evidence for the Monetary Approach © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 47 of 93

Evidence for the Monetary Approach • There are two possible reasons why these relationships many not hold exactly in the data. w First, real income growth may change over time, reflecting another source of inflation differentials. w Second, we assumed the money demand parameter L was constant. We relax this assumption in the following section to incorporate interest rates into the model. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 48 of 93

Evidence for the Monetary Approach • There are two possible reasons why these relationships many not hold exactly in the data. w First, real income growth may change over time, reflecting another source of inflation differentials. w Second, we assumed the money demand parameter L was constant. We relax this assumption in the following section to incorporate interest rates into the model. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 48 of 93

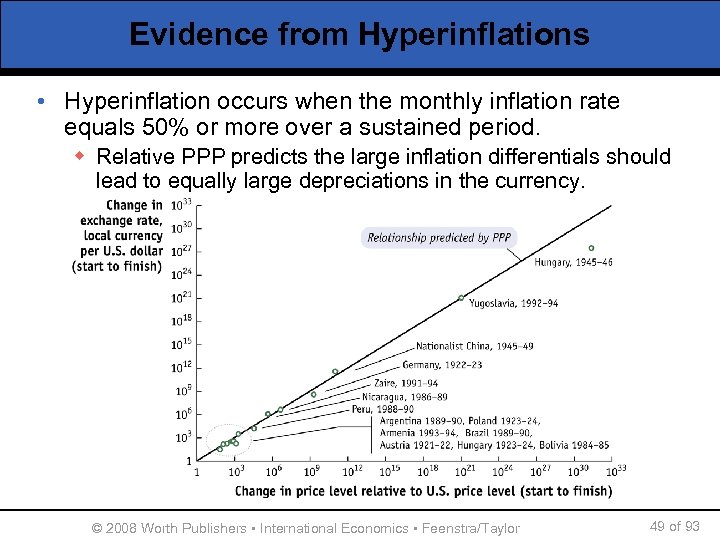

Evidence from Hyperinflations • Hyperinflation occurs when the monthly inflation rate equals 50% or more over a sustained period. w Relative PPP predicts the large inflation differentials should lead to equally large depreciations in the currency. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 49 of 93

Evidence from Hyperinflations • Hyperinflation occurs when the monthly inflation rate equals 50% or more over a sustained period. w Relative PPP predicts the large inflation differentials should lead to equally large depreciations in the currency. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 49 of 93

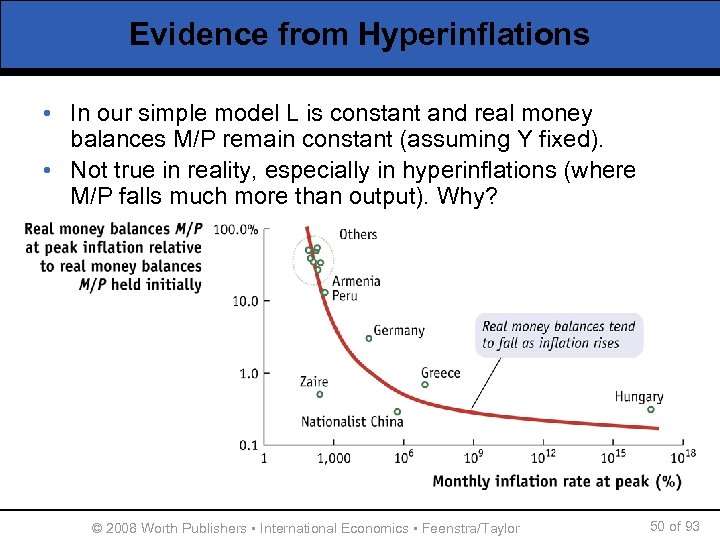

Evidence from Hyperinflations • In our simple model L is constant and real money balances M/P remain constant (assuming Y fixed). • Not true in reality, especially in hyperinflations (where M/P falls much more than output). Why? © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 50 of 93

Evidence from Hyperinflations • In our simple model L is constant and real money balances M/P remain constant (assuming Y fixed). • Not true in reality, especially in hyperinflations (where M/P falls much more than output). Why? © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 50 of 93

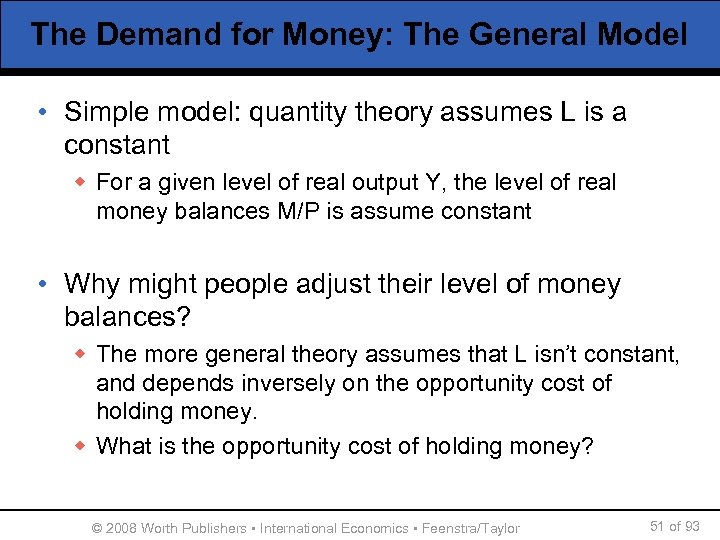

The Demand for Money: The General Model • Simple model: quantity theory assumes L is a constant w For a given level of real output Y, the level of real money balances M/P is assume constant • Why might people adjust their level of money balances? w The more general theory assumes that L isn’t constant, and depends inversely on the opportunity cost of holding money. w What is the opportunity cost of holding money? © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 51 of 93

The Demand for Money: The General Model • Simple model: quantity theory assumes L is a constant w For a given level of real output Y, the level of real money balances M/P is assume constant • Why might people adjust their level of money balances? w The more general theory assumes that L isn’t constant, and depends inversely on the opportunity cost of holding money. w What is the opportunity cost of holding money? © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 51 of 93

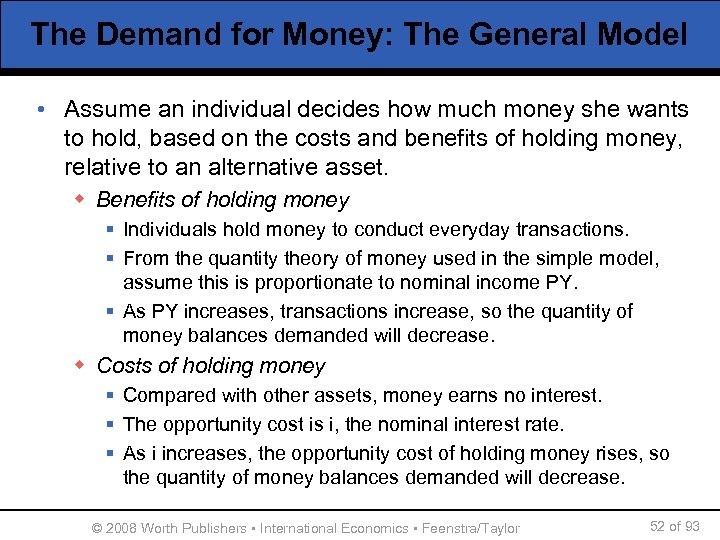

The Demand for Money: The General Model • Assume an individual decides how much money she wants to hold, based on the costs and benefits of holding money, relative to an alternative asset. w Benefits of holding money § Individuals hold money to conduct everyday transactions. § From the quantity theory of money used in the simple model, assume this is proportionate to nominal income PY. § As PY increases, transactions increase, so the quantity of money balances demanded will decrease. w Costs of holding money § Compared with other assets, money earns no interest. § The opportunity cost is i, the nominal interest rate. § As i increases, the opportunity cost of holding money rises, so the quantity of money balances demanded will decrease. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 52 of 93

The Demand for Money: The General Model • Assume an individual decides how much money she wants to hold, based on the costs and benefits of holding money, relative to an alternative asset. w Benefits of holding money § Individuals hold money to conduct everyday transactions. § From the quantity theory of money used in the simple model, assume this is proportionate to nominal income PY. § As PY increases, transactions increase, so the quantity of money balances demanded will decrease. w Costs of holding money § Compared with other assets, money earns no interest. § The opportunity cost is i, the nominal interest rate. § As i increases, the opportunity cost of holding money rises, so the quantity of money balances demanded will decrease. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 52 of 93

The Demand for Money: The General Model • Moving from the individual or household level up to the aggregate or macroeconomic level, we can infer that the aggregate money demand will behave similarly: w All else equal, a rise in national dollar income (nominal income) will cause a proportional increase in transactions and, hence, in aggregate money demand. w All else equal, a rise in the nominal interest rate will cause the aggregate demand for money to fall. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 53 of 93

The Demand for Money: The General Model • Moving from the individual or household level up to the aggregate or macroeconomic level, we can infer that the aggregate money demand will behave similarly: w All else equal, a rise in national dollar income (nominal income) will cause a proportional increase in transactions and, hence, in aggregate money demand. w All else equal, a rise in the nominal interest rate will cause the aggregate demand for money to fall. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 53 of 93

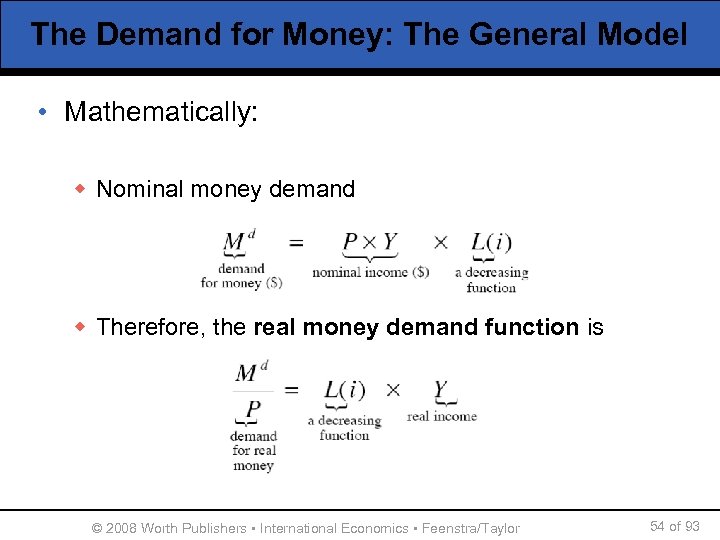

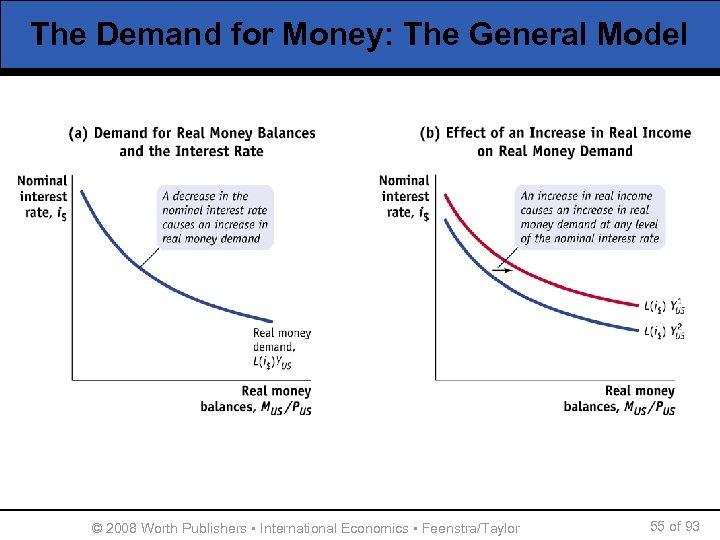

The Demand for Money: The General Model • Mathematically: w Nominal money demand w Therefore, the real money demand function is © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 54 of 93

The Demand for Money: The General Model • Mathematically: w Nominal money demand w Therefore, the real money demand function is © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 54 of 93

The Demand for Money: The General Model © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 55 of 93

The Demand for Money: The General Model © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 55 of 93

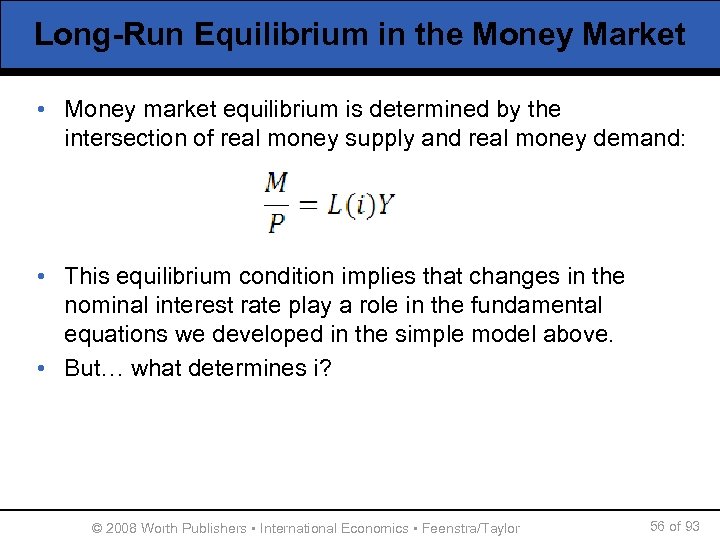

Long-Run Equilibrium in the Money Market • Money market equilibrium is determined by the intersection of real money supply and real money demand: • This equilibrium condition implies that changes in the nominal interest rate play a role in the fundamental equations we developed in the simple model above. • But… what determines i? © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 56 of 93

Long-Run Equilibrium in the Money Market • Money market equilibrium is determined by the intersection of real money supply and real money demand: • This equilibrium condition implies that changes in the nominal interest rate play a role in the fundamental equations we developed in the simple model above. • But… what determines i? © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 56 of 93

Inflation and Interest Rates in the Long Run • Recall: We are building a long run theory w Much is unchanged in the general model as compared to the simple model. w Same key assumptions: § price flexibility § PPP determines the behavior of exchange rates § monetary model for the determination of prices • Modification: w The addition of the term L(i) in the monetary model is only useful if we have a theory of where the interest rate comes from in the long run. w What can we do? Take PPP and UIP and see what they imply in the long run… © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 57 of 93

Inflation and Interest Rates in the Long Run • Recall: We are building a long run theory w Much is unchanged in the general model as compared to the simple model. w Same key assumptions: § price flexibility § PPP determines the behavior of exchange rates § monetary model for the determination of prices • Modification: w The addition of the term L(i) in the monetary model is only useful if we have a theory of where the interest rate comes from in the long run. w What can we do? Take PPP and UIP and see what they imply in the long run… © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 57 of 93

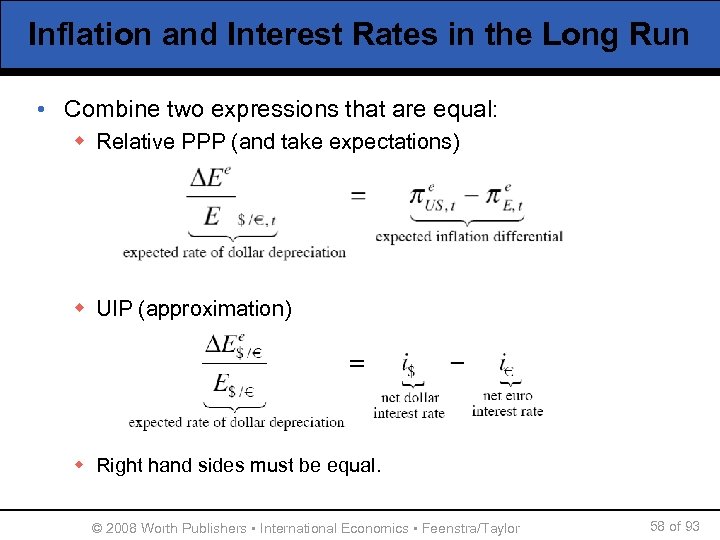

Inflation and Interest Rates in the Long Run • Combine two expressions that are equal: w Relative PPP (and take expectations) w UIP (approximation) w Right hand sides must be equal. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 58 of 93

Inflation and Interest Rates in the Long Run • Combine two expressions that are equal: w Relative PPP (and take expectations) w UIP (approximation) w Right hand sides must be equal. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 58 of 93

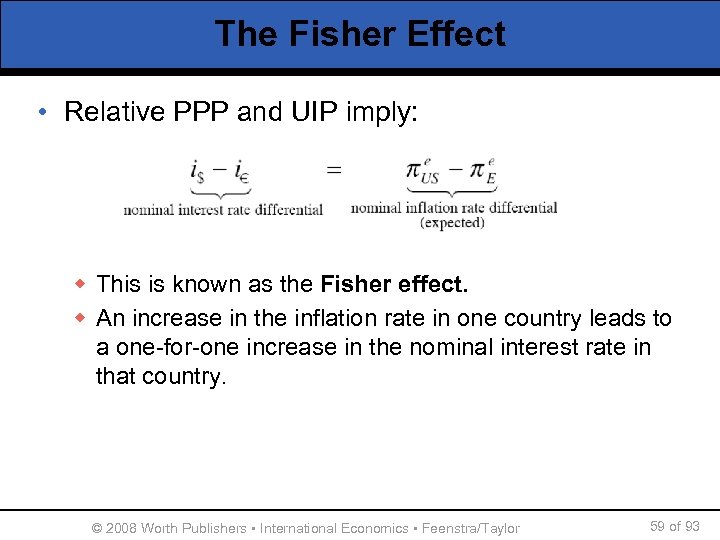

The Fisher Effect • Relative PPP and UIP imply: w This is known as the Fisher effect. w An increase in the inflation rate in one country leads to a one-for-one increase in the nominal interest rate in that country. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 59 of 93

The Fisher Effect • Relative PPP and UIP imply: w This is known as the Fisher effect. w An increase in the inflation rate in one country leads to a one-for-one increase in the nominal interest rate in that country. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 59 of 93

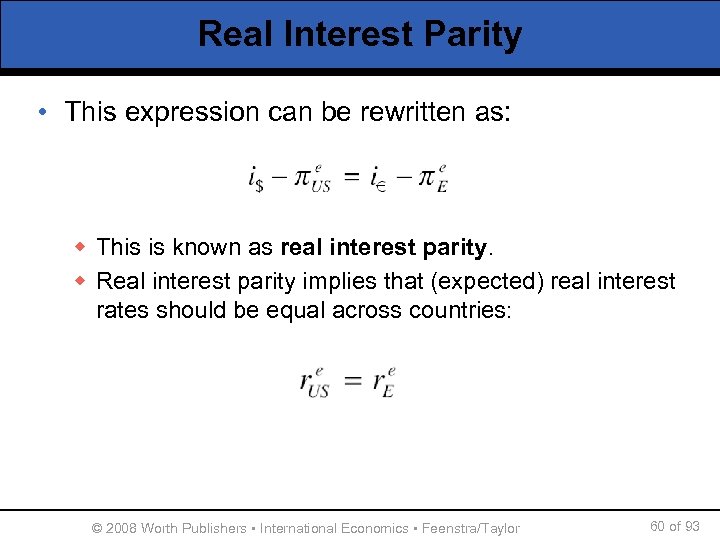

Real Interest Parity • This expression can be rewritten as: w This is known as real interest parity. w Real interest parity implies that (expected) real interest rates should be equal across countries: © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 60 of 93

Real Interest Parity • This expression can be rewritten as: w This is known as real interest parity. w Real interest parity implies that (expected) real interest rates should be equal across countries: © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 60 of 93

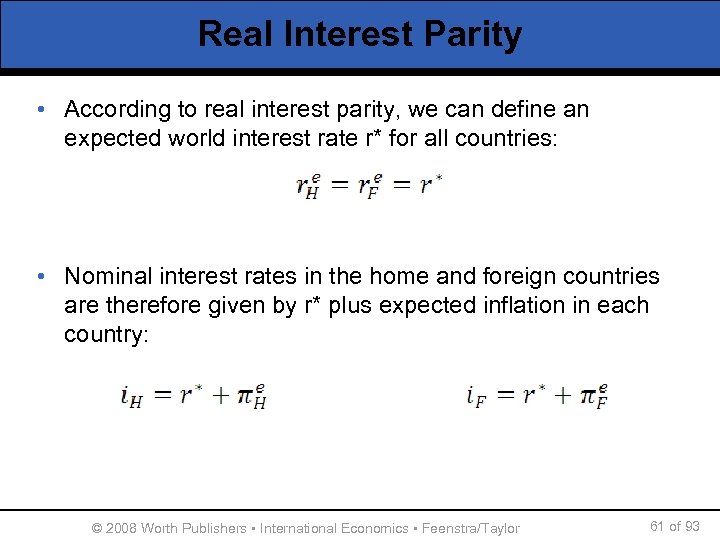

Real Interest Parity • According to real interest parity, we can define an expected world interest rate r* for all countries: • Nominal interest rates in the home and foreign countries are therefore given by r* plus expected inflation in each country: © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 61 of 93

Real Interest Parity • According to real interest parity, we can define an expected world interest rate r* for all countries: • Nominal interest rates in the home and foreign countries are therefore given by r* plus expected inflation in each country: © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 61 of 93

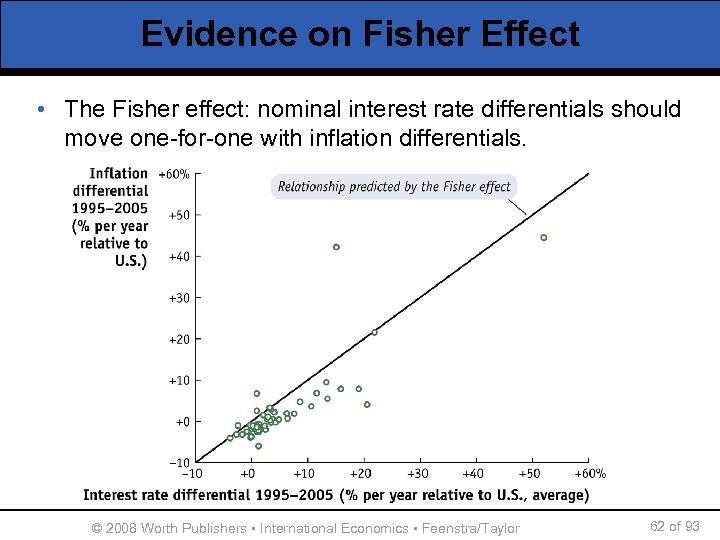

Evidence on Fisher Effect • The Fisher effect: nominal interest rate differentials should move one-for-one with inflation differentials. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 62 of 93

Evidence on Fisher Effect • The Fisher effect: nominal interest rate differentials should move one-for-one with inflation differentials. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 62 of 93

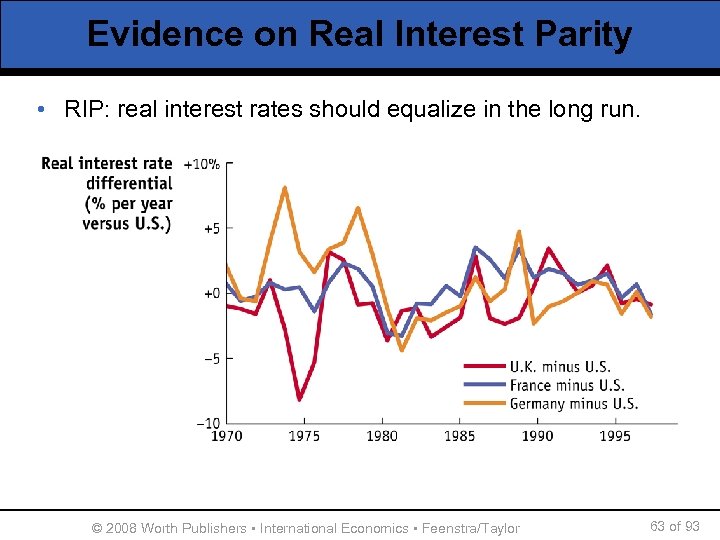

Evidence on Real Interest Parity • RIP: real interest rates should equalize in the long run. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 63 of 93

Evidence on Real Interest Parity • RIP: real interest rates should equalize in the long run. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 63 of 93

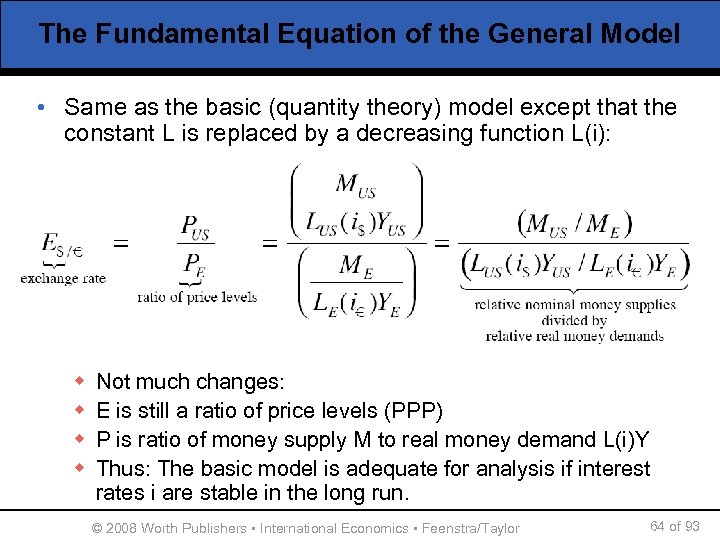

The Fundamental Equation of the General Model • Same as the basic (quantity theory) model except that the constant L is replaced by a decreasing function L(i): w w Not much changes: E is still a ratio of price levels (PPP) P is ratio of money supply M to real money demand L(i)Y Thus: The basic model is adequate for analysis if interest rates i are stable in the long run. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 64 of 93

The Fundamental Equation of the General Model • Same as the basic (quantity theory) model except that the constant L is replaced by a decreasing function L(i): w w Not much changes: E is still a ratio of price levels (PPP) P is ratio of money supply M to real money demand L(i)Y Thus: The basic model is adequate for analysis if interest rates i are stable in the long run. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 64 of 93

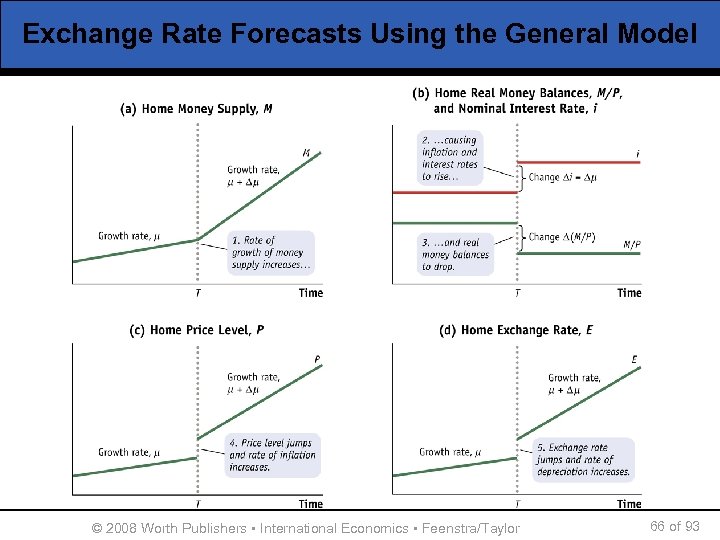

Exchange Rate Forecasts Using the General Model • Revisit Policy Predictions, Case 2 to see what’s new: • Assumptions w Both countries § Constant money growth rate m , fixed level of output Y w Foreign § Money growth m is zero, inflation p is zero w Home § Money growth m is positive, inflation p is positive • Home increases its rate of money growth m by D m w What happens to key variables in the long run (flexible price) case, when we use the general model and L = L(i) § NB: Assume inflation and interest rate are constant before and after the policy change. We can verify assumption later as a consistency check. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 65 of 93

Exchange Rate Forecasts Using the General Model • Revisit Policy Predictions, Case 2 to see what’s new: • Assumptions w Both countries § Constant money growth rate m , fixed level of output Y w Foreign § Money growth m is zero, inflation p is zero w Home § Money growth m is positive, inflation p is positive • Home increases its rate of money growth m by D m w What happens to key variables in the long run (flexible price) case, when we use the general model and L = L(i) § NB: Assume inflation and interest rate are constant before and after the policy change. We can verify assumption later as a consistency check. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 65 of 93

Exchange Rate Forecasts Using the General Model © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 66 of 93

Exchange Rate Forecasts Using the General Model © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 66 of 93

Exchange Rate Forecasts Using the General Model • Results of an increase in the money growth rate: w The home inflation rate increases by D m w The nominal interest rate increases by D m w A one-time decrease in real money balances M/P because of the increase in the nominal interest rate. w A one-time increase in P and E. w The rate of exchange rate depreciation increases by D m percentage points after E jumps up. • The importance of expectations w If people know that a change in money growth is coming in the future, they will adjust their expectations of the inflation rate and exchange rates accordingly. w Even if a change is not implemented, expectation of a change has consequences for the variables in the model. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 67 of 93

Exchange Rate Forecasts Using the General Model • Results of an increase in the money growth rate: w The home inflation rate increases by D m w The nominal interest rate increases by D m w A one-time decrease in real money balances M/P because of the increase in the nominal interest rate. w A one-time increase in P and E. w The rate of exchange rate depreciation increases by D m percentage points after E jumps up. • The importance of expectations w If people know that a change in money growth is coming in the future, they will adjust their expectations of the inflation rate and exchange rates accordingly. w Even if a change is not implemented, expectation of a change has consequences for the variables in the model. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 67 of 93

Monetary Regimes and Exchange Rate Regimes • Policy makers are concerned with costs of inflation w Inflation is unpopular and has macroeconomic costs w These costs are severe when inflation rates are high. w This is why inflation targets are desirable. • The monetary approach shows how policymakers can choose among different nominal anchors to achieve their inflation goal. w The monetary regime they choose specifies what are the rules, objectives, policies followed by the central bank. w The exchange rate regime is part of the monetary regime, and must be consistent with it; is the exchange rate fixed or floating? © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 68 of 93

Monetary Regimes and Exchange Rate Regimes • Policy makers are concerned with costs of inflation w Inflation is unpopular and has macroeconomic costs w These costs are severe when inflation rates are high. w This is why inflation targets are desirable. • The monetary approach shows how policymakers can choose among different nominal anchors to achieve their inflation goal. w The monetary regime they choose specifies what are the rules, objectives, policies followed by the central bank. w The exchange rate regime is part of the monetary regime, and must be consistent with it; is the exchange rate fixed or floating? © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 68 of 93

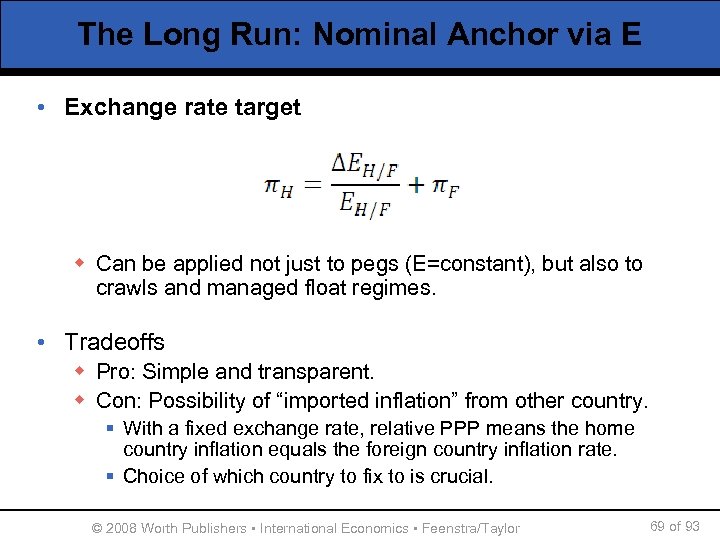

The Long Run: Nominal Anchor via E • Exchange rate target w Can be applied not just to pegs (E=constant), but also to crawls and managed float regimes. • Tradeoffs w Pro: Simple and transparent. w Con: Possibility of “imported inflation” from other country. § With a fixed exchange rate, relative PPP means the home country inflation equals the foreign country inflation rate. § Choice of which country to fix to is crucial. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 69 of 93

The Long Run: Nominal Anchor via E • Exchange rate target w Can be applied not just to pegs (E=constant), but also to crawls and managed float regimes. • Tradeoffs w Pro: Simple and transparent. w Con: Possibility of “imported inflation” from other country. § With a fixed exchange rate, relative PPP means the home country inflation equals the foreign country inflation rate. § Choice of which country to fix to is crucial. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 69 of 93

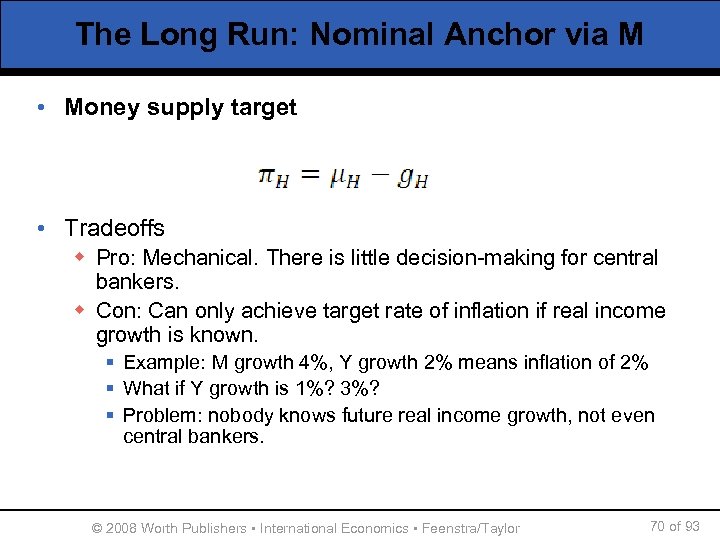

The Long Run: Nominal Anchor via M • Money supply target • Tradeoffs w Pro: Mechanical. There is little decision-making for central bankers. w Con: Can only achieve target rate of inflation if real income growth is known. § Example: M growth 4%, Y growth 2% means inflation of 2% § What if Y growth is 1%? 3%? § Problem: nobody knows future real income growth, not even central bankers. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 70 of 93

The Long Run: Nominal Anchor via M • Money supply target • Tradeoffs w Pro: Mechanical. There is little decision-making for central bankers. w Con: Can only achieve target rate of inflation if real income growth is known. § Example: M growth 4%, Y growth 2% means inflation of 2% § What if Y growth is 1%? 3%? § Problem: nobody knows future real income growth, not even central bankers. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 70 of 93

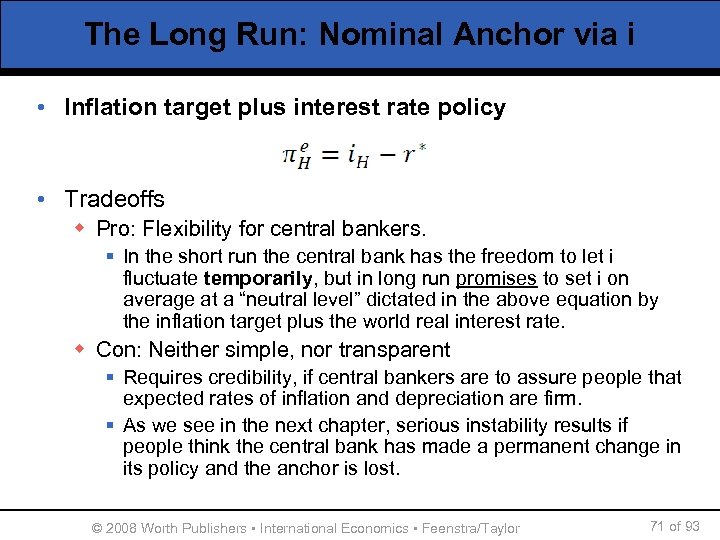

The Long Run: Nominal Anchor via i • Inflation target plus interest rate policy • Tradeoffs w Pro: Flexibility for central bankers. § In the short run the central bank has the freedom to let i fluctuate temporarily, but in long run promises to set i on average at a “neutral level” dictated in the above equation by the inflation target plus the world real interest rate. w Con: Neither simple, nor transparent § Requires credibility, if central bankers are to assure people that expected rates of inflation and depreciation are firm. § As we see in the next chapter, serious instability results if people think the central bank has made a permanent change in its policy and the anchor is lost. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 71 of 93

The Long Run: Nominal Anchor via i • Inflation target plus interest rate policy • Tradeoffs w Pro: Flexibility for central bankers. § In the short run the central bank has the freedom to let i fluctuate temporarily, but in long run promises to set i on average at a “neutral level” dictated in the above equation by the inflation target plus the world real interest rate. w Con: Neither simple, nor transparent § Requires credibility, if central bankers are to assure people that expected rates of inflation and depreciation are firm. § As we see in the next chapter, serious instability results if people think the central bank has made a permanent change in its policy and the anchor is lost. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 71 of 93

The Choice of a Nominal Anchor • There are two important considerations in choosing a monetary regime. • Choosing more than one target (or weighting) can work sometimes, but it may be problematic. w Different regimes may call for different policy responses, causing confusion. w Success in anchoring inflation may be affected by a more vague and discretionary policy framework. • A country with a nominal anchor sacrifices monetary policy autonomy in the long run. w Hitting the target will only be possible if the central bank picks the right levels of M or E or i. w Unpopular choices at times. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 72 of 93

The Choice of a Nominal Anchor • There are two important considerations in choosing a monetary regime. • Choosing more than one target (or weighting) can work sometimes, but it may be problematic. w Different regimes may call for different policy responses, causing confusion. w Success in anchoring inflation may be affected by a more vague and discretionary policy framework. • A country with a nominal anchor sacrifices monetary policy autonomy in the long run. w Hitting the target will only be possible if the central bank picks the right levels of M or E or i. w Unpopular choices at times. © 2008 Worth Publishers ▪ International Economics ▪ Feenstra/Taylor 72 of 93