330e1972ab21be1a983b31aaa2183faf.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 154

1 Sequence Alignment Bioinformatics Algorithms Based on © Pevzner and Jones Revised 2015 The capacity to blunder slightly is the real marvel of DNA. Without this special attribute, we would still be anaerobic bacteria and there would be no music. - Lewis Thomas

Outline Homework Introduce Scoring Matrices Some mismatches are better than others Solve Alignment with Affine Gap Penalties Continuing deletion more common than starting one Linear Space Alignment Multiple Alignment

3 Matching Sequences Odds that all match = p 6 = 1/4096 ~ 0. 00024 Odds that none match. Odds are q 6 = 36/46 ~ 0. 178 Let’s break down the case where there is a single match. The odds that the first match, but none other do, is pq 5 But we could match in any of the six spots, so the odds of a single match are 6 pq 5 = 6 x 0. 25 x (0. 75)5 ~ 0. 356

4 Matching Sequences To match the first two, the odds are p 2 q 4. But to capture all possible matches with two correct, we need to see how many ways we can pick 2 out of 6. This is the combinatorial coefficient C(6, 2), pronounced “Six choose two” and equal to 6 x 5 / 2 = 15. This fits the patterns above: we have C(6, 0) = 1, C(6, 1) = 6, and C(6, 6) = 1. In general, the odds of matching are C(6, k)pkq 6 -k

5 Repeats Which is largest k for which 4^k + k <= 1, 000? k = 10 is a bit too large, so must settle for 9: you will probably have a repeat of length 10, but you will always have a repeat of length 9

6 Repeats What is the longest repeat that has a 50% chance of appearing?

7 Repeats What is the longest repeat that has a 50% chance of appearing? 16 bins

8 Repeats What is the longest repeat that has a 50% chance of appearing? 64 bins

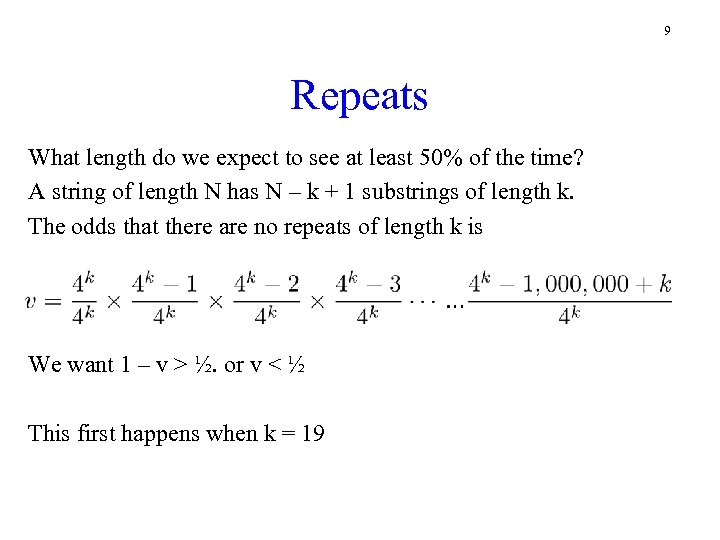

9 Repeats What length do we expect to see at least 50% of the time? A string of length N has N – k + 1 substrings of length k. The odds that there are no repeats of length k is We want 1 – v > ½. or v < ½ This first happens when k = 19

10 A few words on real numbers In bad old days there were flakey floating point chips IEEE 754 is a standard that has been widely adopted in modern chips. Addresses many serious problems. We still need to know three terms Overflow – 10 lbs of sugar in a 5 lb sack Underflow – Numbers too small to distinguish from 0 Machine Epsilon – Distance between 1. 0 and the next number we can represent Numerical Analysis goes over this and much more

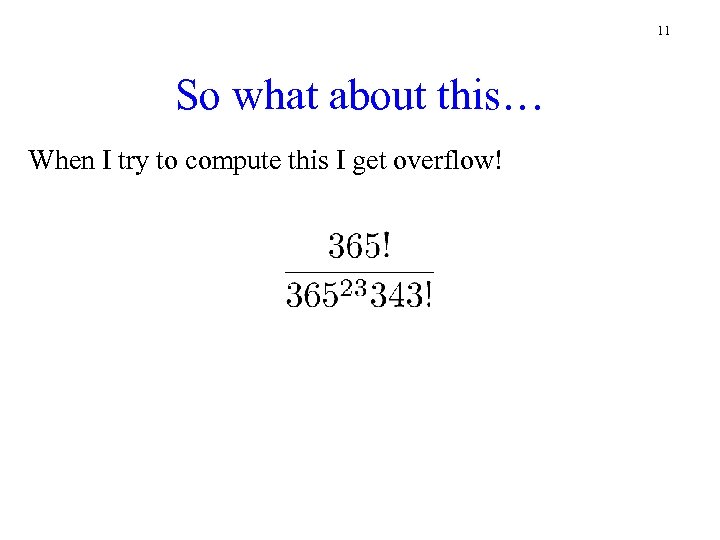

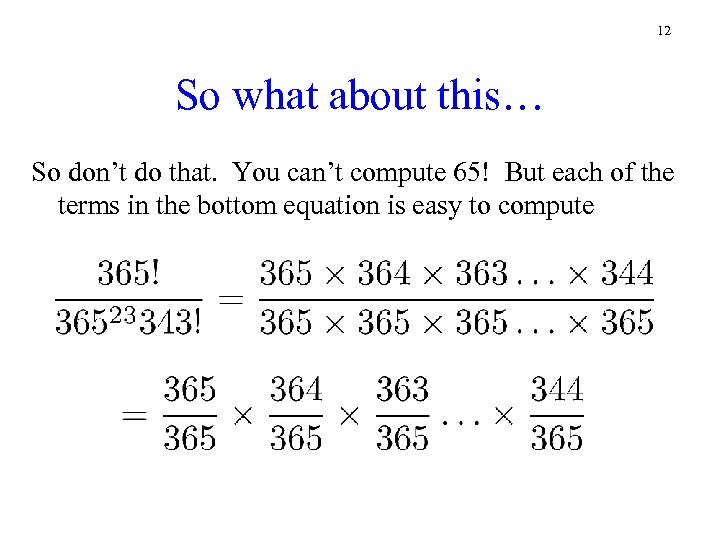

11 So what about this… When I try to compute this I get overflow!

12 So what about this… So don’t do that. You can’t compute 65! But each of the terms in the bottom equation is easy to compute

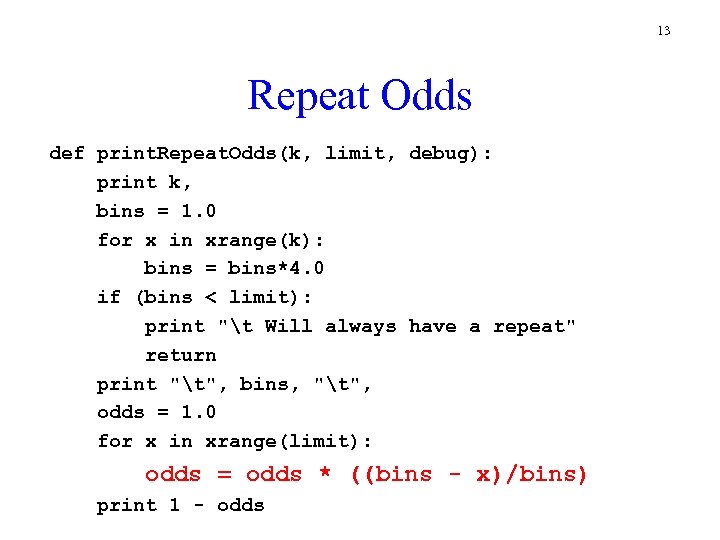

13 Repeat Odds def print. Repeat. Odds(k, limit, debug): print k, bins = 1. 0 for x in xrange(k): bins = bins*4. 0 if (bins < limit): print "t Will always have a repeat" return print "t", bins, "t", odds = 1. 0 for x in xrange(limit): odds = odds * ((bins - x)/bins) print 1 - odds

14 Repeat Odds def print. Repeat. Odds(k, limit, debug): . . . print "t", bins, "t", odds = 1. 0 for x in xrange(limit): odds = odds * ((bins - x)/bins) print 1 - odds print "n. K: ", "t. Bins: ", "t. Odds of a repeat" for k in xrange(1, 22): print. Repeat. Odds(k, 1000000 - k + 1, False)

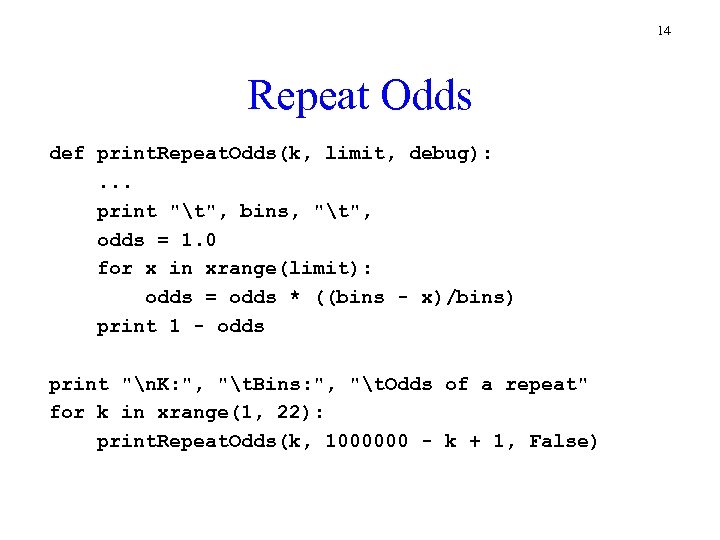

15 Palindrome output $ python find. Palindrome. py. . /data/EColi. fasta. . . 3 103 AAA TTT 3 103 AAATTT 4 102 AAAA TTTT 4 102 AAAATTTT 5 101 TAAAA TTTTA. . . 10 849177 CATGGTTATG CATAACCATG 11 849176 GCATGGTTATG CATAACCATGC 12 849175 TGCATGGTTATG CATAACCATGCA 13 849174 CTGCATGGTTATG CATAACCATGCAG 14 849173 TCTGCATGGTTATG CATAACCATGCAGA 15 849172 TTCTGCATGGTTATG CATAACCATGCAGAA

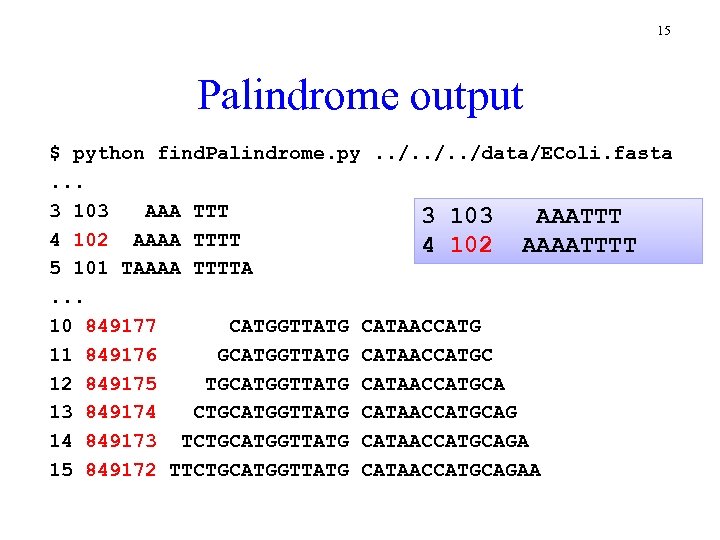

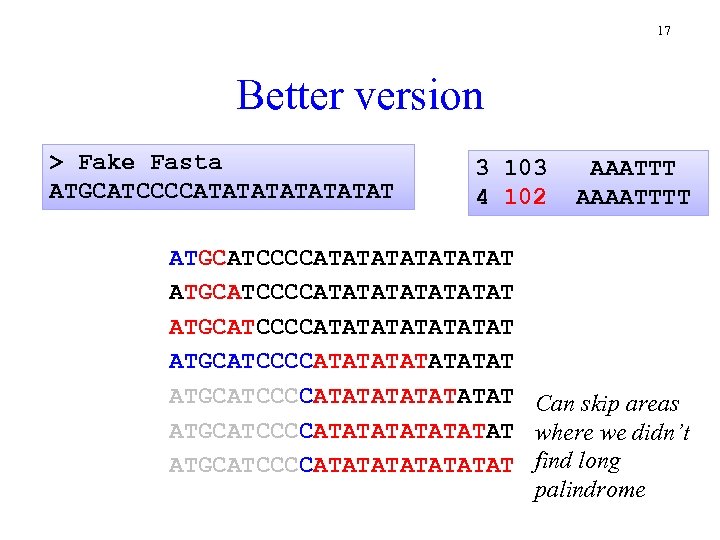

16 How much work? > Fake Fasta ATGCATCCCCATATATATATATAT ATGCATCCCCATATATATATATAT ATGCATCCCCATATATAT Do we need to ATGCATCCCCATATATAT pass over initial data each pass?

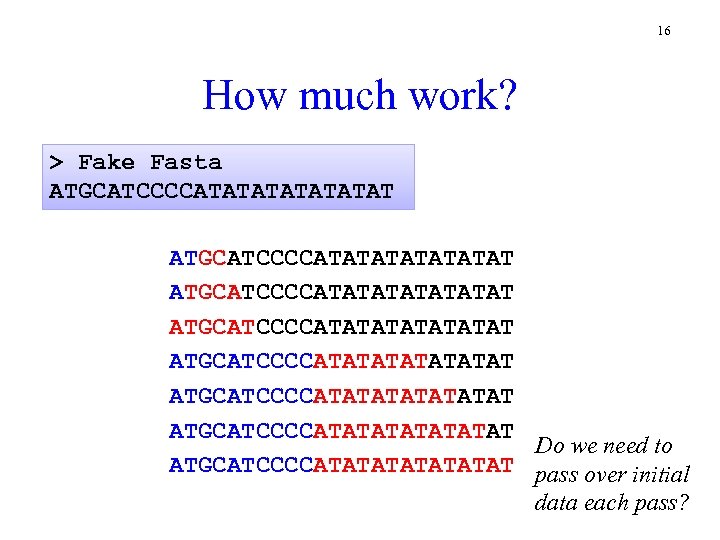

17 Better version > Fake Fasta ATGCATCCCCATATATAT 3 103 4 102 AAATTT AAAATTTT ATGCATCCCCATATATATATATAT ATGCATCCCCATATATAT Can skip areas ATGCATCCCCATATATAT where we didn’t ATGCATCCCCATATATAT find long palindrome

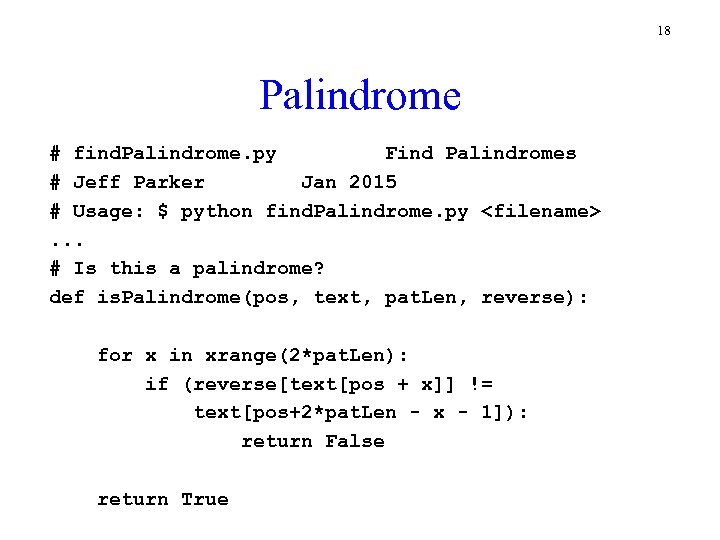

18 Palindrome # find. Palindrome. py Find Palindromes # Jeff Parker Jan 2015 # Usage: $ python find. Palindrome. py <filename>. . . # Is this a palindrome? def is. Palindrome(pos, text, pat. Len, reverse): for x in xrange(2*pat. Len): if (reverse[text[pos + x]] != text[pos+2*pat. Len - x - 1]): return False return True

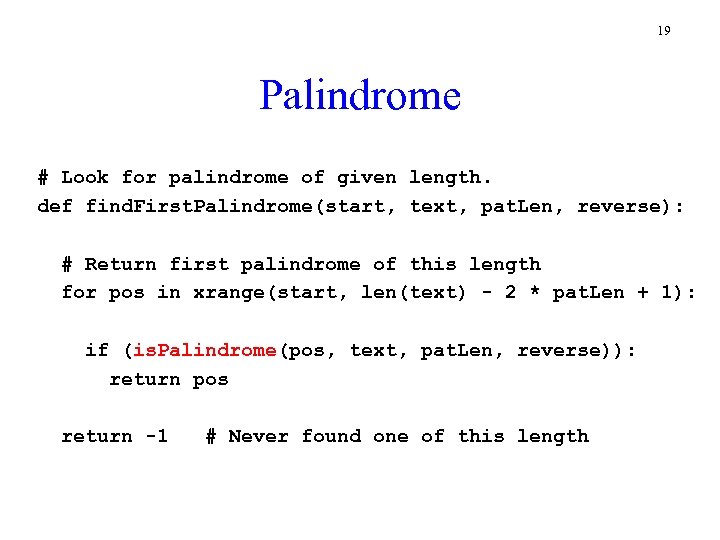

19 Palindrome # Look for palindrome of given length. def find. First. Palindrome(start, text, pat. Len, reverse): # Return first palindrome of this length for pos in xrange(start, len(text) - 2 * pat. Len + 1): if (is. Palindrome(pos, text, pat. Len, reverse)): return pos return -1 # Never found one of this length

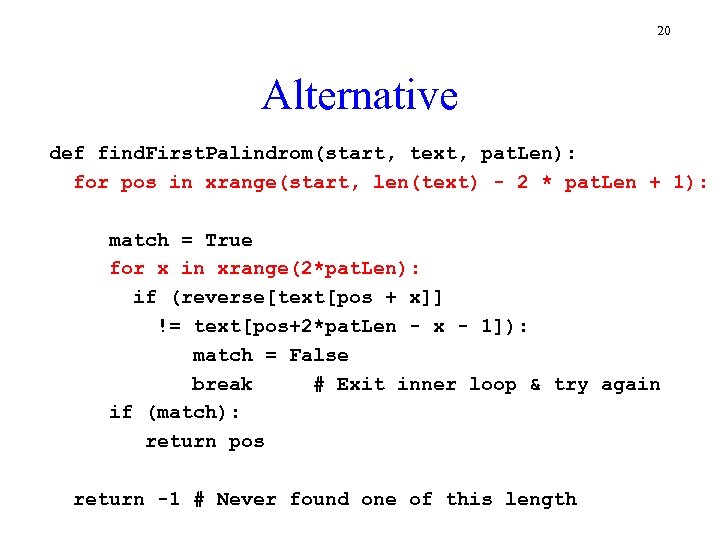

20 Alternative def find. First. Palindrom(start, text, pat. Len): for pos in xrange(start, len(text) - 2 * pat. Len + 1): match = True for x in xrange(2*pat. Len): if (reverse[text[pos + x]] != text[pos+2*pat. Len - x - 1]): match = False break # Exit inner loop & try again if (match): return pos return -1 # Never found one of this length

![21 Palindrome reverse = { }; reverse['A'] = reverse['T'] = reverse['G'] = reverse['C'] = 21 Palindrome reverse = { }; reverse['A'] = reverse['T'] = reverse['G'] = reverse['C'] =](https://present5.com/presentation/330e1972ab21be1a983b31aaa2183faf/image-21.jpg)

21 Palindrome reverse = { }; reverse['A'] = reverse['T'] = reverse['G'] = reverse['C'] = 'T’ 'A’ 'C’ 'G’ 3 103 AAATTT 4 102 AAAATTTT 5 101 TAAAATTTTA Need to step back. . . pat. Len = 1 pos = find. First. Palindrome(1, text, pat. Len, reverse) while (pos > -1): print pat. Len, pos+1, text[pos: pos+(2*pat. Len) ] pat. Len = pat. Len + 1 start = max(pos-1, 0) # But don’t go past 0! pos = find. First. Palindrome(start, text, pat. Len, reverse)

![22 Find all ORFs def find. All. Orf(text, limit): lst = [] # Look 22 Find all ORFs def find. All. Orf(text, limit): lst = [] # Look](https://present5.com/presentation/330e1972ab21be1a983b31aaa2183faf/image-22.jpg)

22 Find all ORFs def find. All. Orf(text, limit): lst = [] # Look for start in each of three reading frames. for off. Set in xrange(3): pos = off. Set while (pos > -1): [pos, y, ln] = find. ORF(text, pos, limit) if (pos > 0): # Go around again item = ["+", off. Set+1, pos+1, y, ln] lst. append(item) pos = pos + ln # Go past the ORF return lst

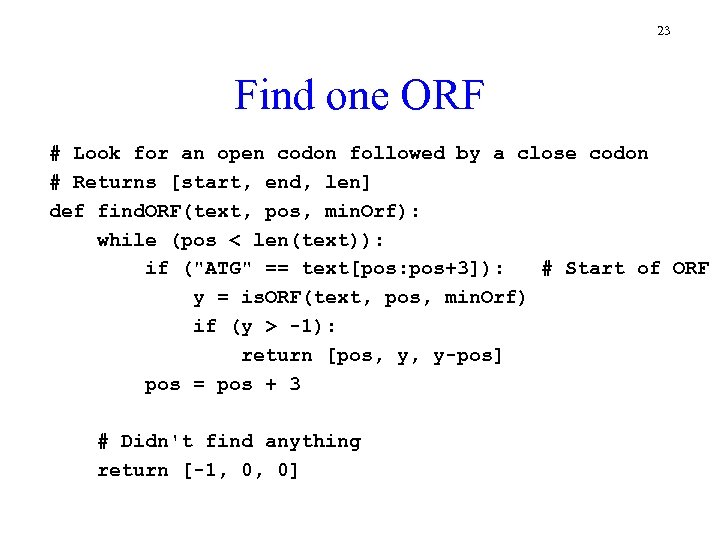

23 Find one ORF # Look for an open codon followed by a close codon # Returns [start, end, len] def find. ORF(text, pos, min. Orf): while (pos < len(text)): if ("ATG" == text[pos: pos+3]): # Start of ORF y = is. ORF(text, pos, min. Orf) if (y > -1): return [pos, y, y-pos] pos = pos + 3 # Didn't find anything return [-1, 0, 0]

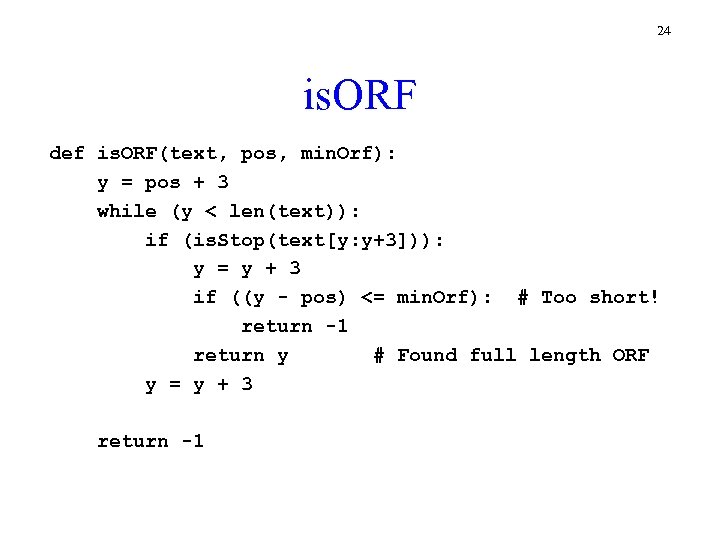

24 is. ORF def is. ORF(text, pos, min. Orf): y = pos + 3 while (y < len(text)): if (is. Stop(text[y: y+3])): y = y + 3 if ((y - pos) <= min. Orf): # Too short! return -1 return y # Found full length ORF y = y + 3 return -1

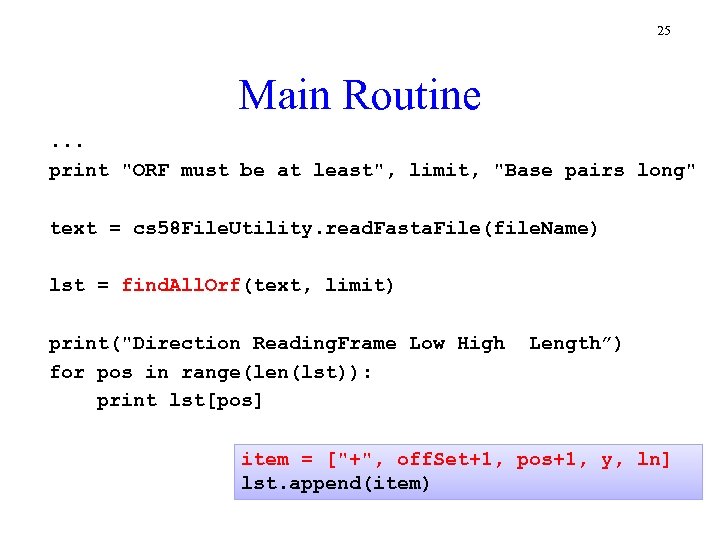

25 Main Routine. . . print "ORF must be at least", limit, "Base pairs long" text = cs 58 File. Utility. read. Fasta. File(file. Name) lst = find. All. Orf(text, limit) print("Direction Reading. Frame Low High for pos in range(len(lst)): print lst[pos] Length”) item = ["+", off. Set+1, pos+1, y, ln] lst. append(item)

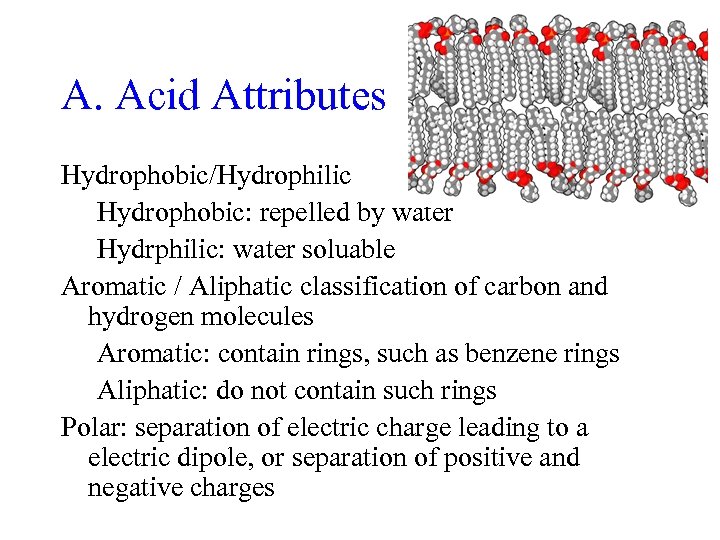

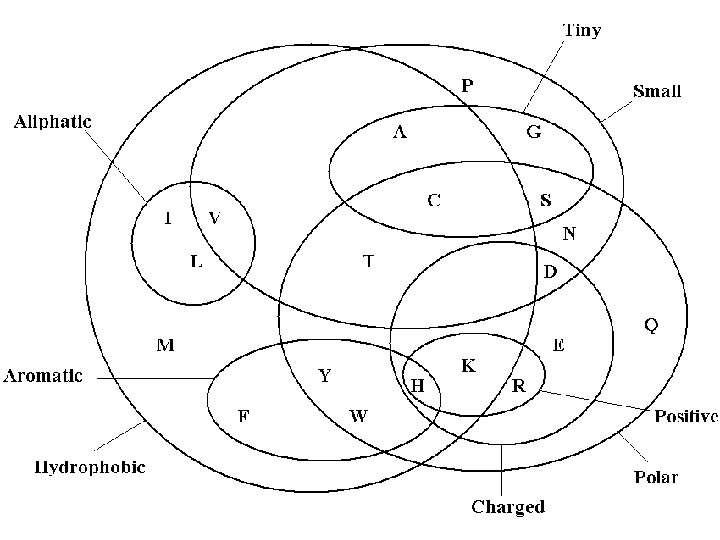

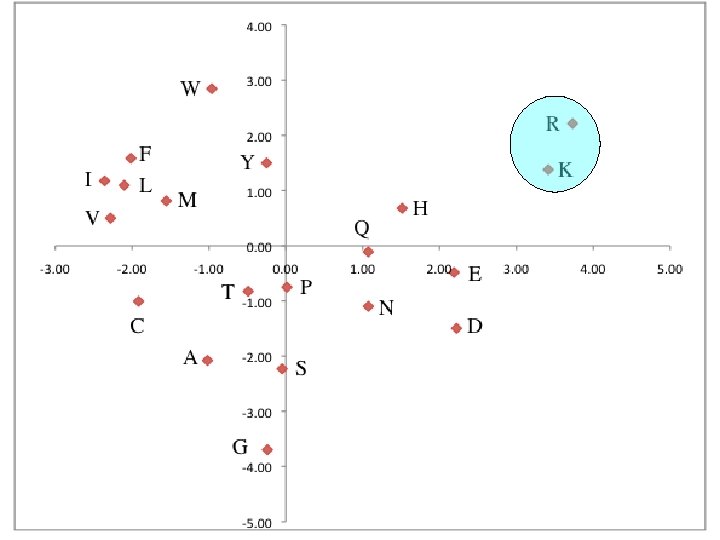

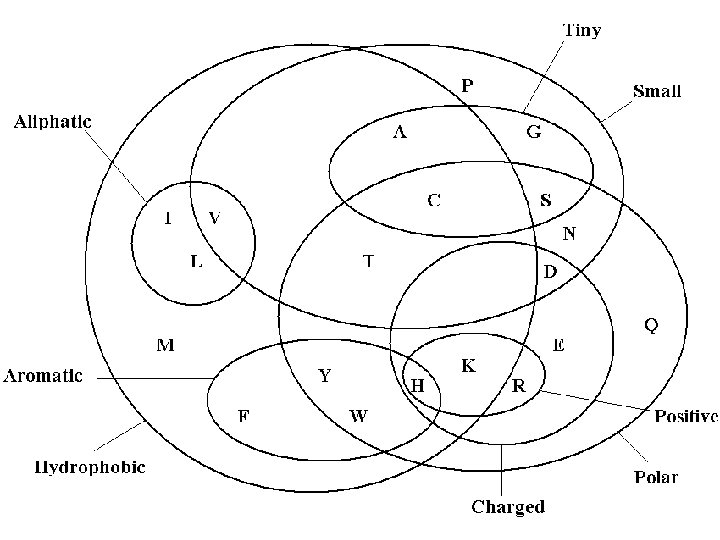

A. Acid Attributes Hydrophobic/Hydrophilic Hydrophobic: repelled by water Hydrphilic: water soluable Aromatic / Aliphatic classification of carbon and hydrogen molecules Aromatic: contain rings, such as benzene rings Aliphatic: do not contain such rings Polar: separation of electric charge leading to a electric dipole, or separation of positive and negative charges

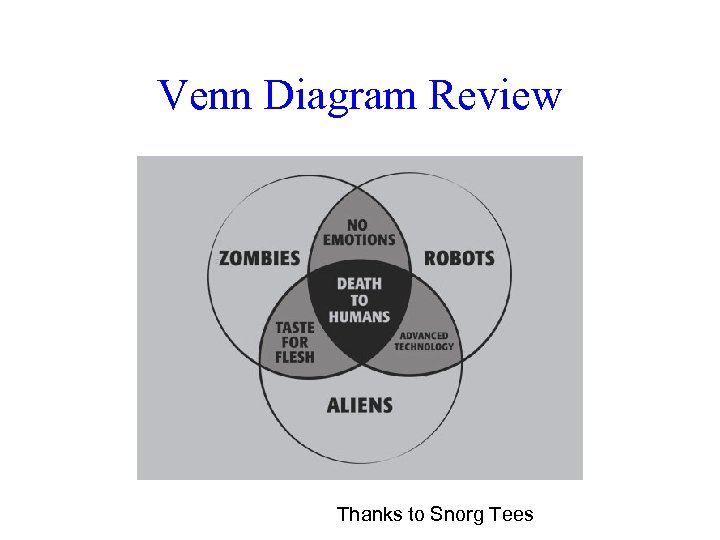

Venn Diagram Review Thanks to Snorg Tees

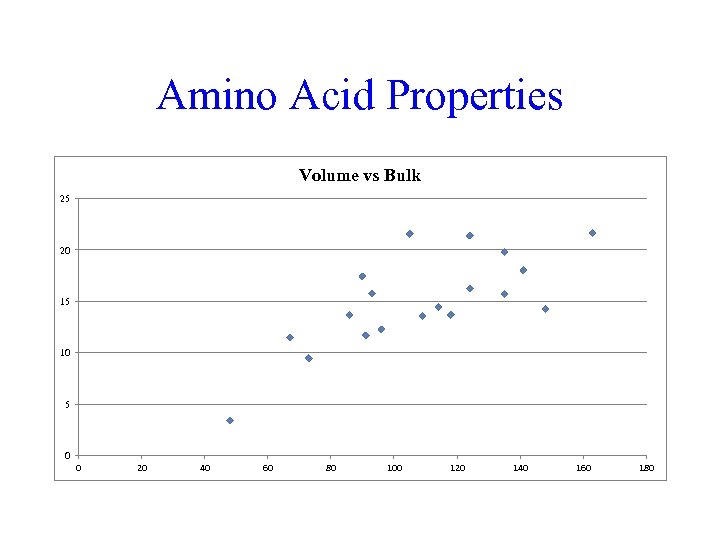

Amino Acid Properties Volume vs Bulk 25 20 15 10 5 0 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180

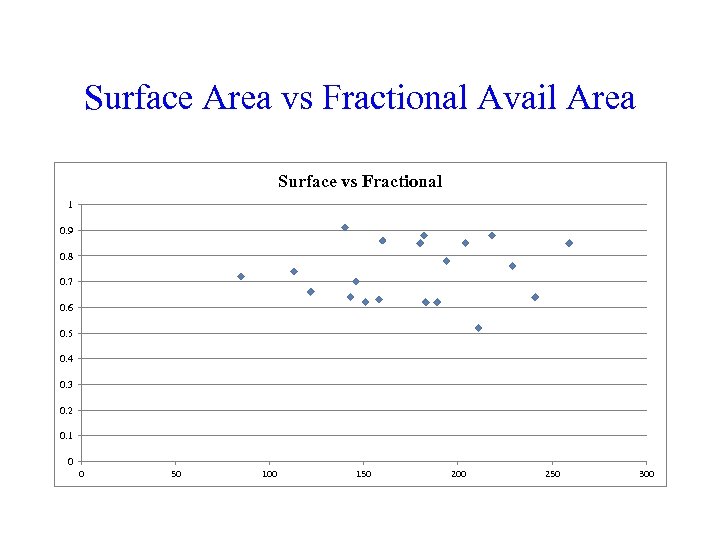

Surface Area vs Fractional Avail Area Surface vs Fractional 1 0. 9 0. 8 0. 7 0. 6 0. 5 0. 4 0. 3 0. 2 0. 1 0 0 50 100 150 200 250 300

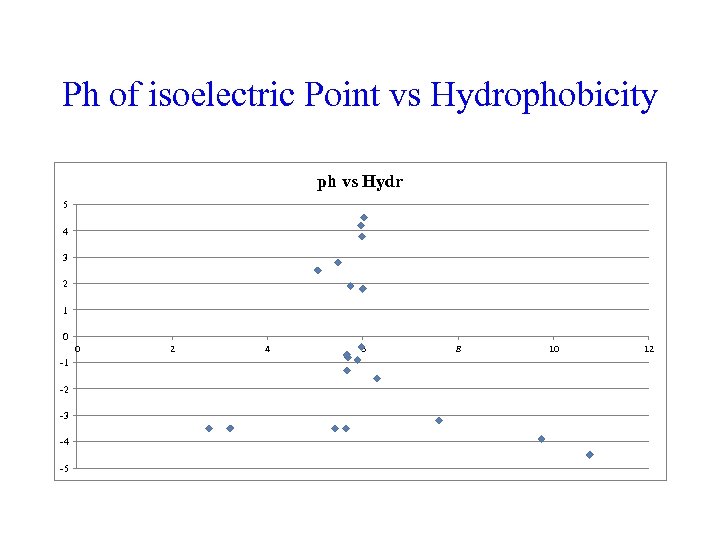

Ph of isoelectric Point vs Hydrophobicity ph vs Hydr 5 4 3 2 1 0 0 -1 -2 -3 -4 -5 2 4 6 8 10 12

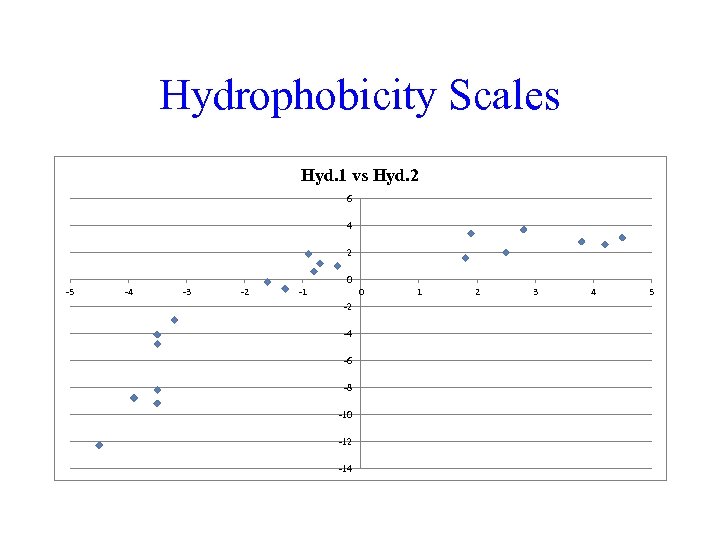

Hydrophobicity Scales Hyd. 1 vs Hyd. 2 6 4 2 0 -5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 -2 -4 -6 -8 -10 -12 -14 1 2 3 4 5

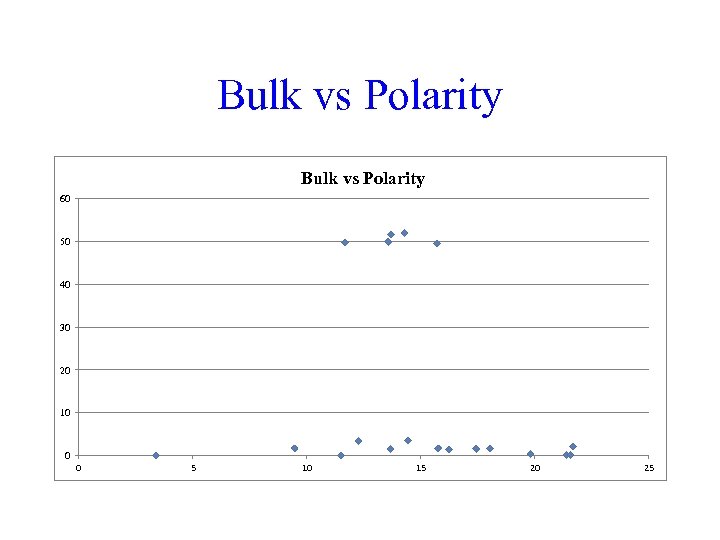

Bulk vs Polarity 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 0 5 10 15 20 25

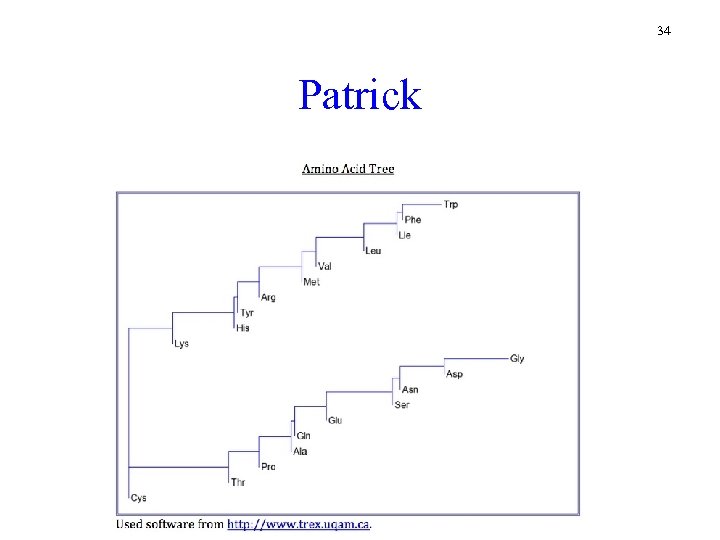

34 Patrick

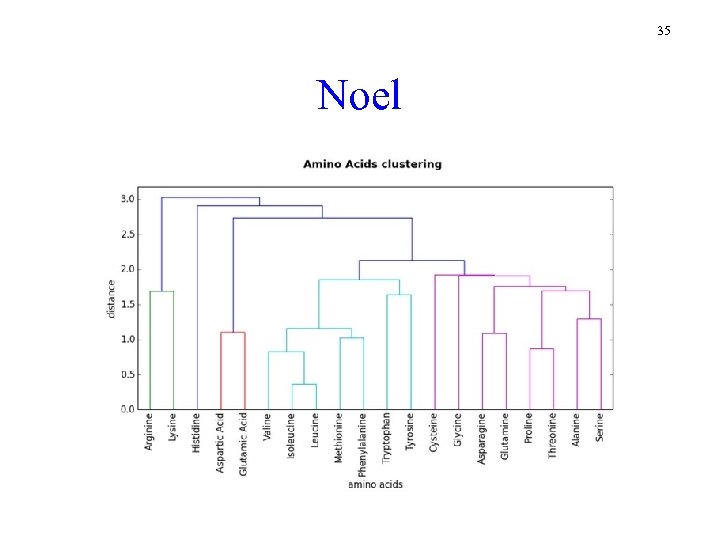

35 Noel

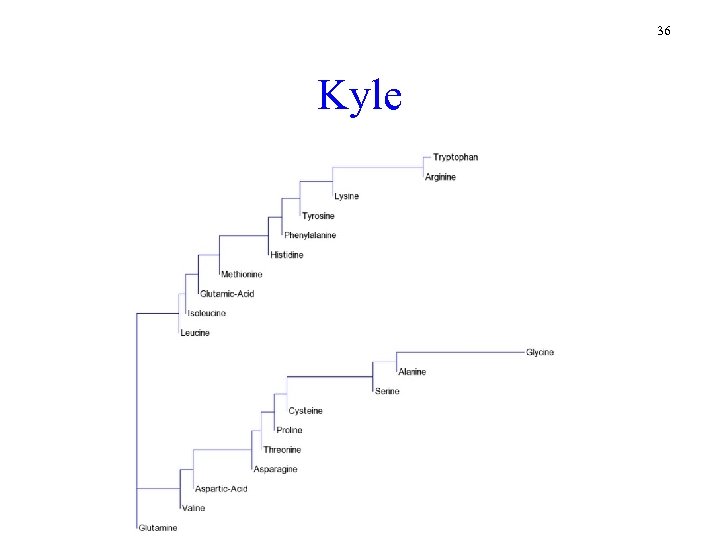

36 Kyle

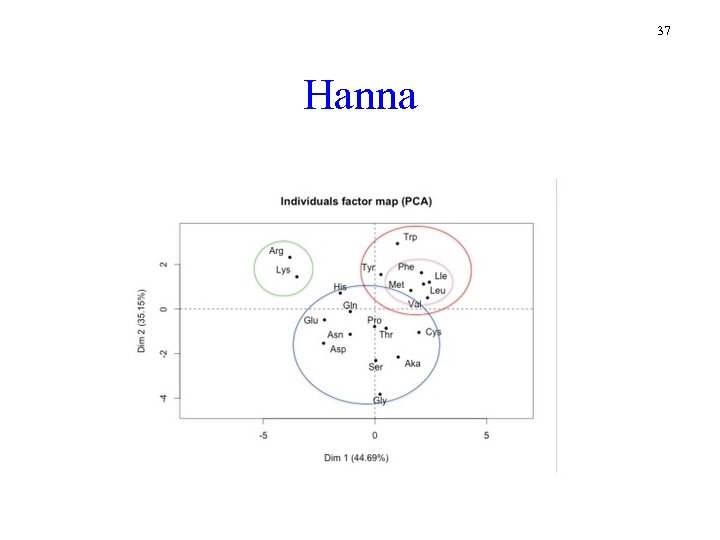

37 Hanna

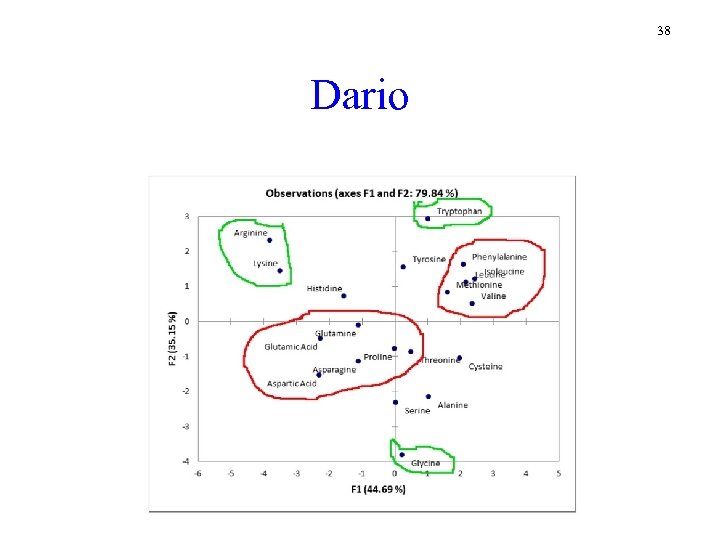

38 Dario

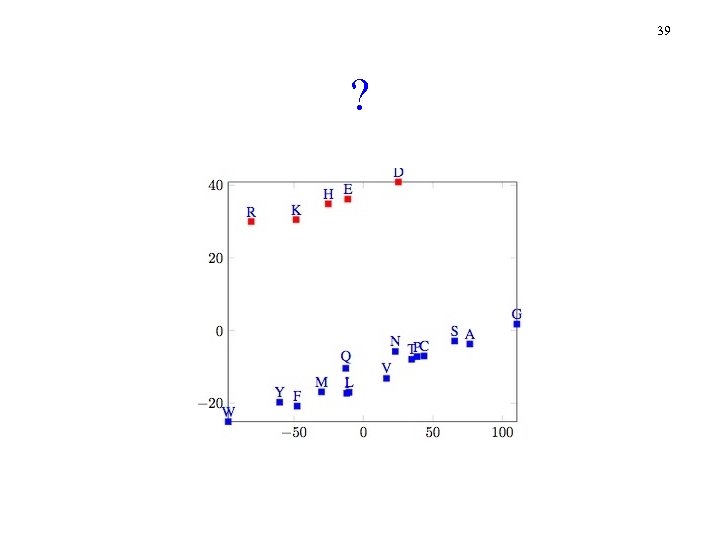

39 ?

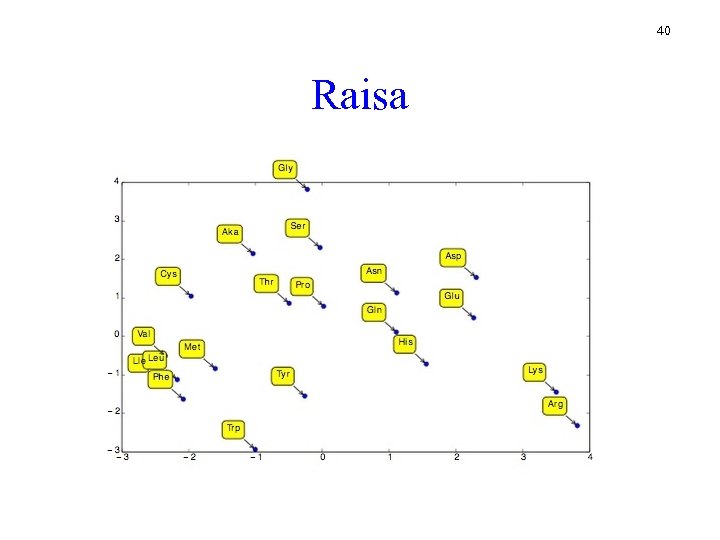

40 Raisa

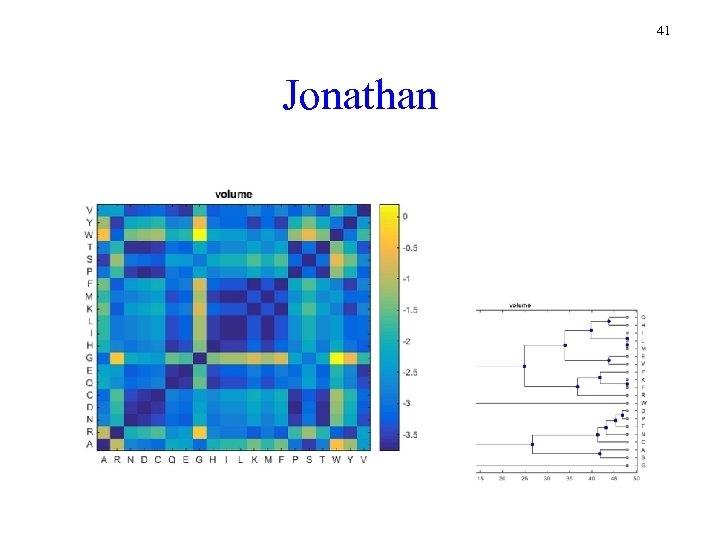

41 Jonathan

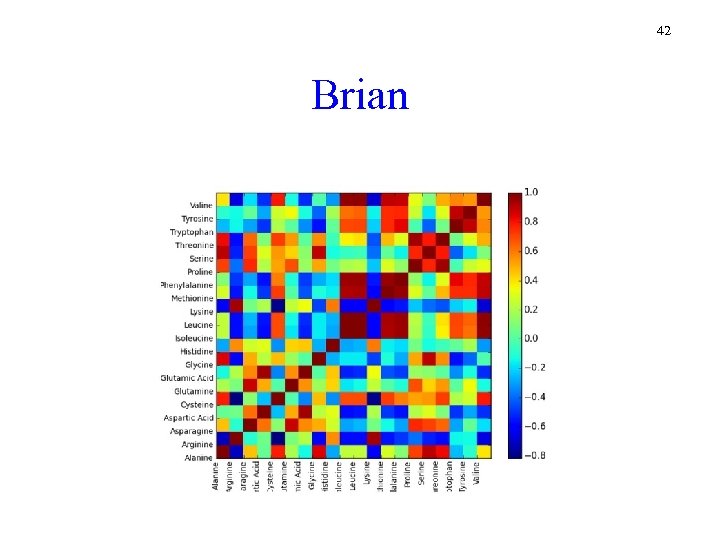

42 Brian

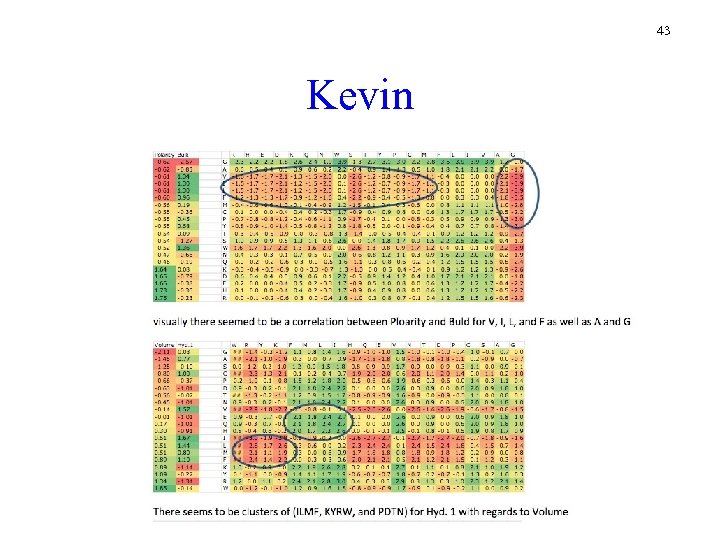

43 Kevin

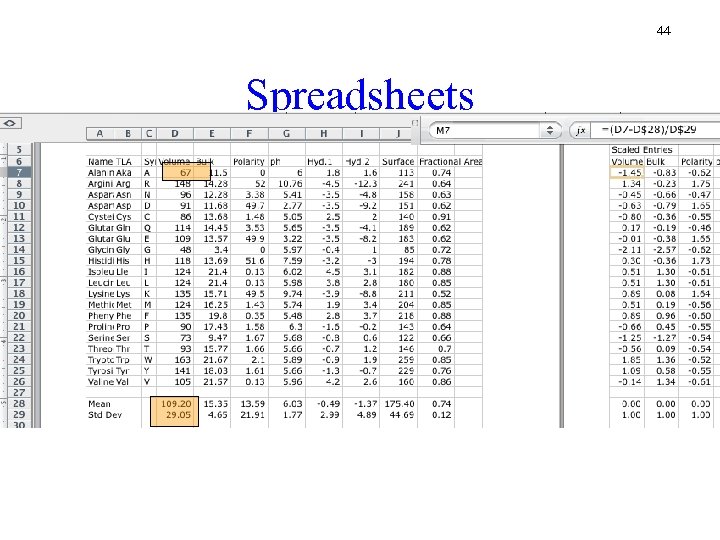

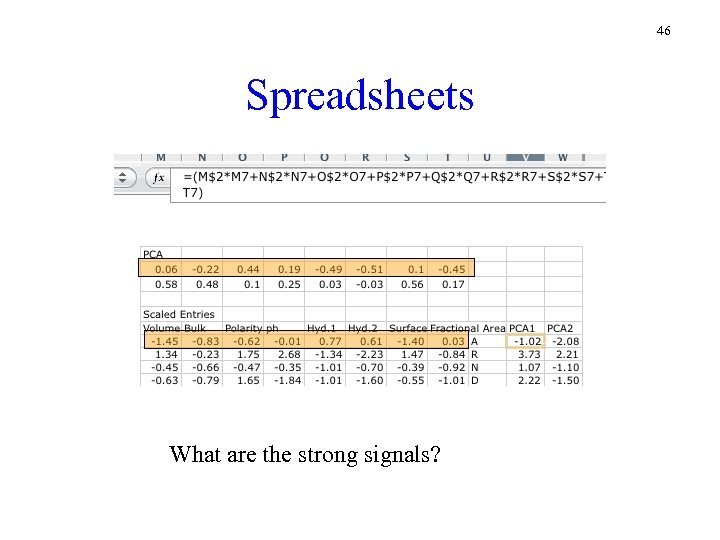

44 Spreadsheets

45 What do sums and differences mean?

46 Spreadsheets What are the strong signals?

47

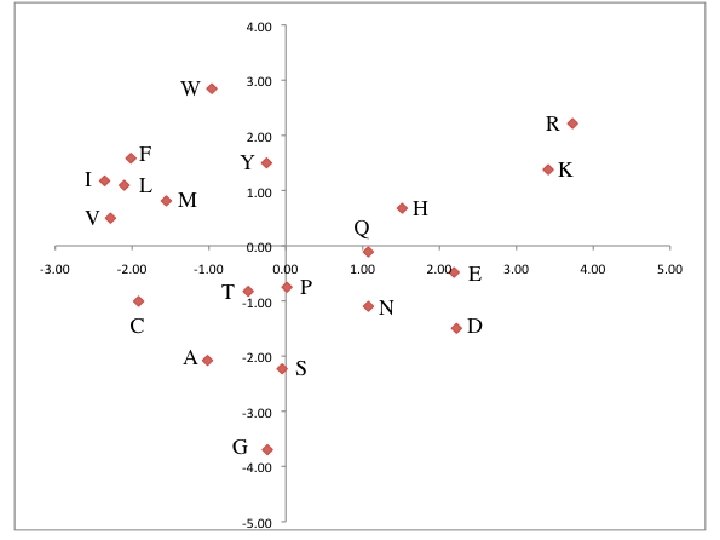

48 Summary Principal Component Analysis is a technique that takes data of multiple dimensions, and finds the “Principal Components” Can make it easier to make sense out of data Note that in this case, we have no evidence (yet) that the components that we have identified have any biological significance We might have started by measuring the wrong things We will get a chance to evaluate this distance matrix when we return to sequence alignment

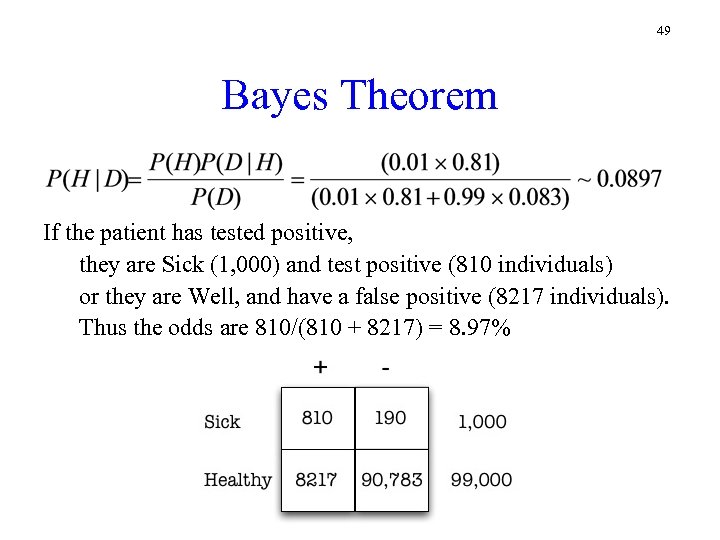

49 Bayes Theorem If the patient has tested positive, they are Sick (1, 000) and test positive (810 individuals) or they are Well, and have a false positive (8217 individuals). Thus the odds are 810/(810 + 8217) = 8. 97%

Outline Homework Introduce Scoring Matrices Some mismatches are better than others Solve Alignment with Affine Gap Penalties Continuing deletion more common than starting one Linear Space Alignment Multiple Alignment

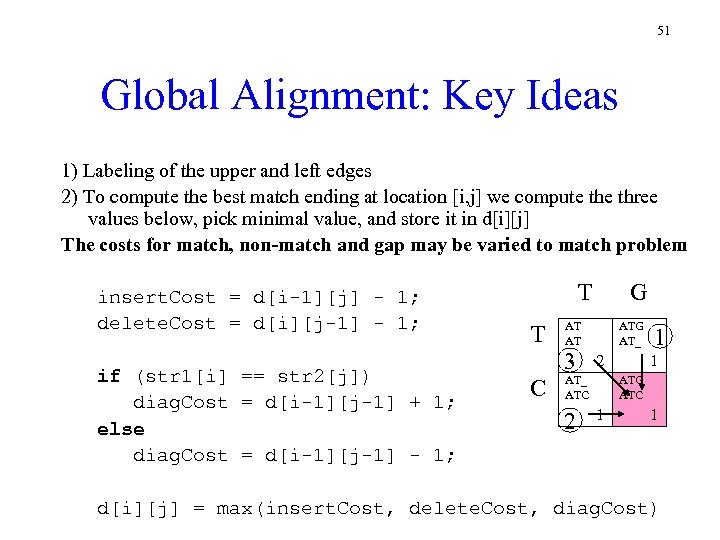

51 Global Alignment: Key Ideas 1) Labeling of the upper and left edges 2) To compute the best match ending at location [i, j] we compute three values below, pick minimal value, and store it in d[i][j] The costs for match, non-match and gap may be varied to match problem insert. Cost = d[i-1][j] - 1; delete. Cost = d[i][j-1] - 1; if (str 1[i] == str 2[j]) diag. Cost = d[i-1][j-1] + 1; else diag. Cost = d[i-1][j-1] - 1; T T G AT AT ATG AT_ 3 C 2 2 1 AT_ ATC 1 1 ATG ATC 1 d[i][j] = max(insert. Cost, delete. Cost, diag. Cost)

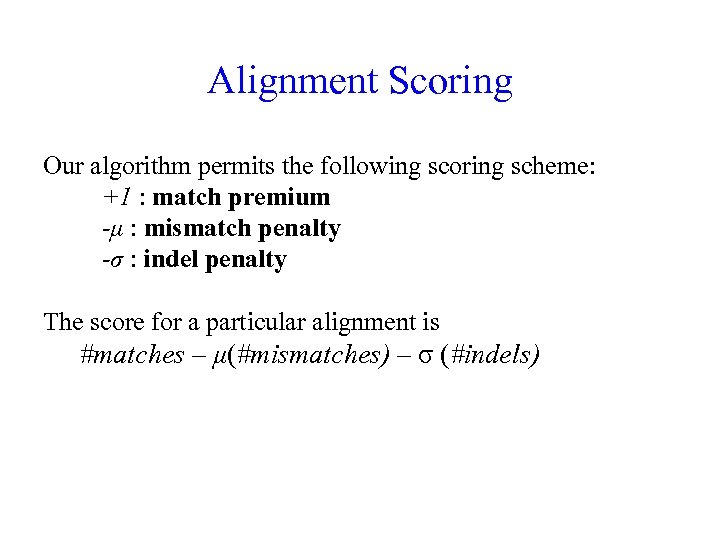

Alignment Scoring Our algorithm permits the following scoring scheme: +1 : match premium -μ : mismatch penalty -σ : indel penalty The score for a particular alignment is #matches – μ(#mismatches) – σ (#indels)

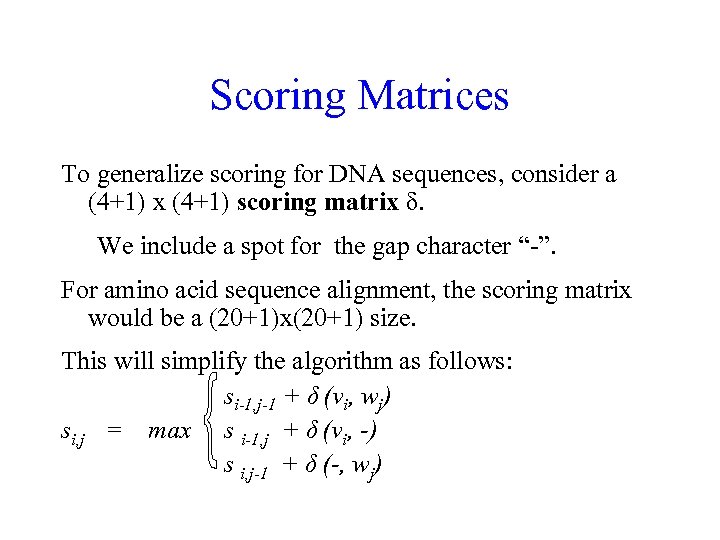

Scoring Matrices To generalize scoring for DNA sequences, consider a (4+1) x (4+1) scoring matrix δ. We include a spot for the gap character “-”. For amino acid sequence alignment, the scoring matrix would be a (20+1)x(20+1) size. This will simplify the algorithm as follows: si-1, j-1 + δ (vi, wj) si, j = max s i-1, j + δ (vi, -) s i, j-1 + δ (-, wj)

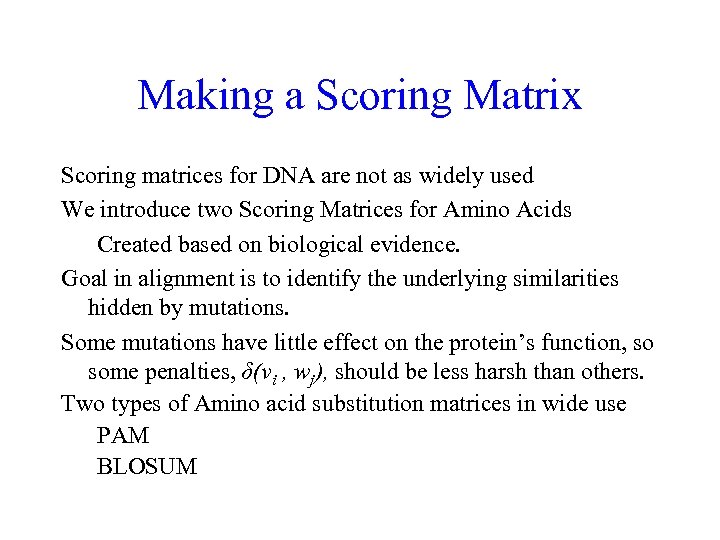

Making a Scoring Matrix Scoring matrices for DNA are not as widely used We introduce two Scoring Matrices for Amino Acids Created based on biological evidence. Goal in alignment is to identify the underlying similarities hidden by mutations. Some mutations have little effect on the protein’s function, so some penalties, δ(vi , wj), should be less harsh than others. Two types of Amino acid substitution matrices in wide use PAM BLOSUM

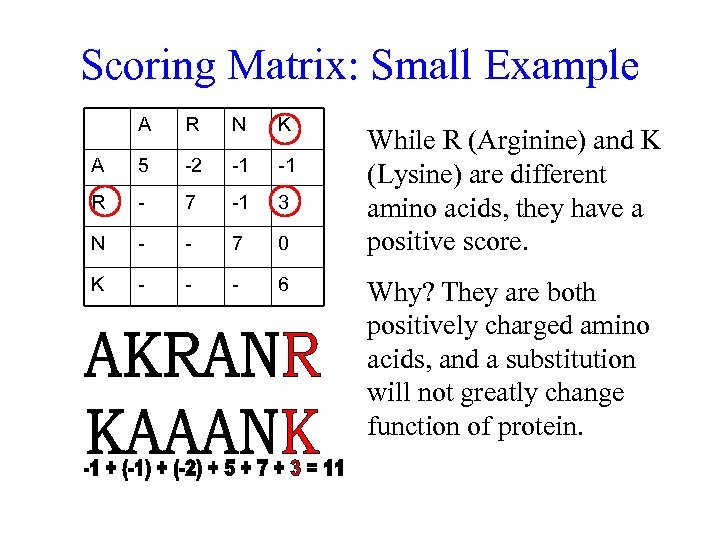

Scoring Matrix: Small Example A R N K A 5 -2 -1 -1 R - 7 -1 3 N - - 7 0 K - - - 6 While R (Arginine) and K (Lysine) are different amino acids, they have a positive score. Why? They are both positively charged amino acids, and a substitution will not greatly change function of protein.

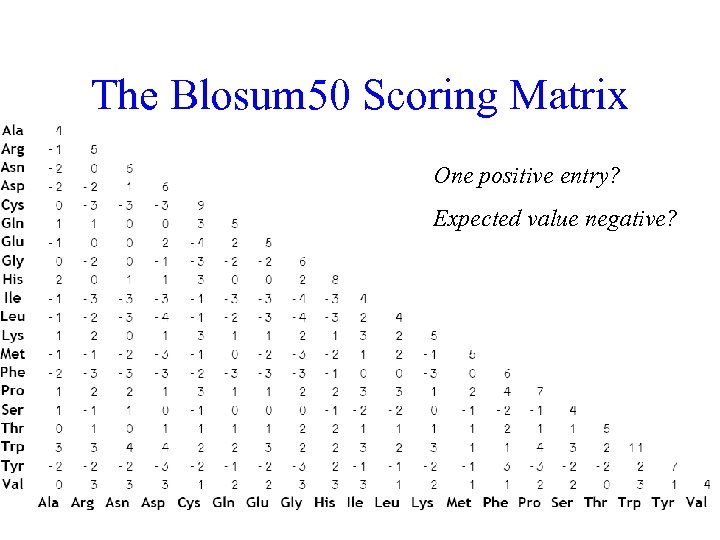

The Blosum 50 Scoring Matrix

Attributes The Cell: A molecular Approach Hydrophobic/Hydrophilic Geoffery Cooper Hydrophobic: repelled by water Hydrphilic: water soluable Aromatic / Aliphatic classification of carbon and hydrogen molecules Aromatic: contain rings, such as benzene rings Aliphatic: do not contain such rings Polar: separation of electric charge leading to a electric dipole, or separation of positive and negative charges

Conservation Amino acid changes that tend to preserve the physico -chemical properties of the original residue Polar to polar aspartate glutamate Nonpolar to nonpolar alanine valine Similarly behaving residues leucine isoleucine

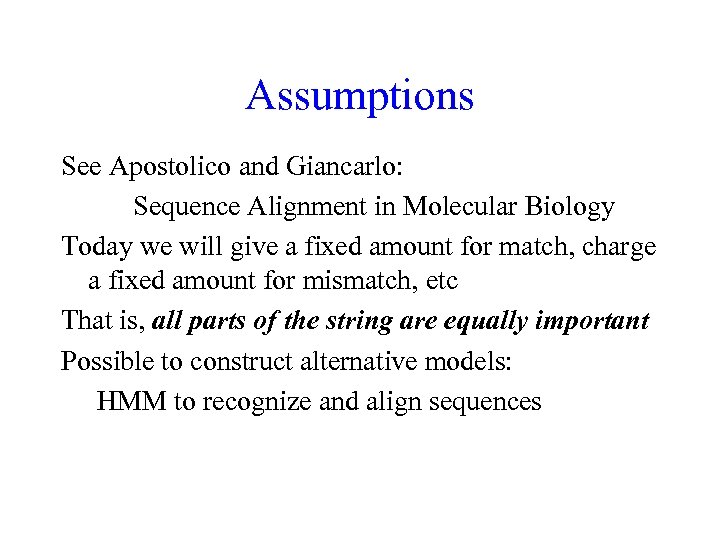

Assumptions See Apostolico and Giancarlo: Sequence Alignment in Molecular Biology Today we will give a fixed amount for match, charge a fixed amount for mismatch, etc That is, all parts of the string are equally important Possible to construct alternative models: HMM to recognize and align sequences

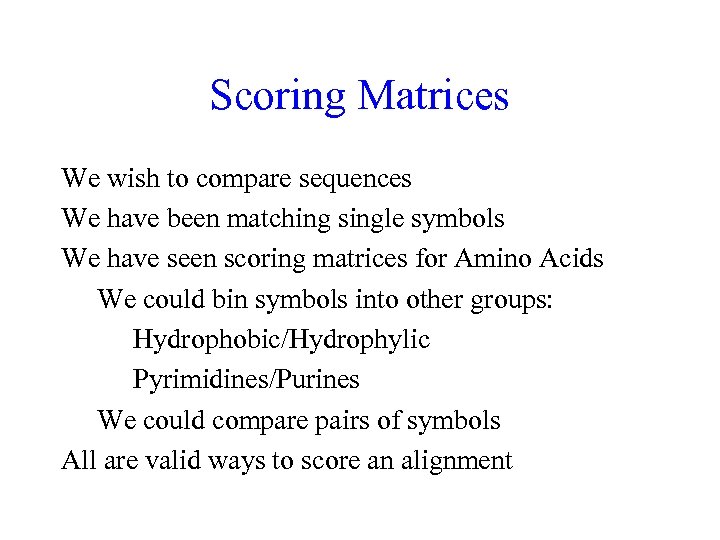

Scoring Matrices We wish to compare sequences We have been matching single symbols We have seen scoring matrices for Amino Acids We could bin symbols into other groups: Hydrophobic/Hydrophylic Pyrimidines/Purines We could compare pairs of symbols All are valid ways to score an alignment

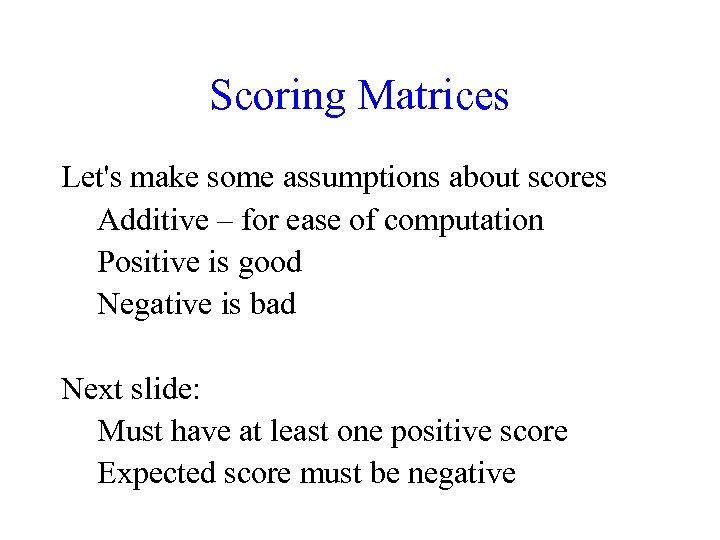

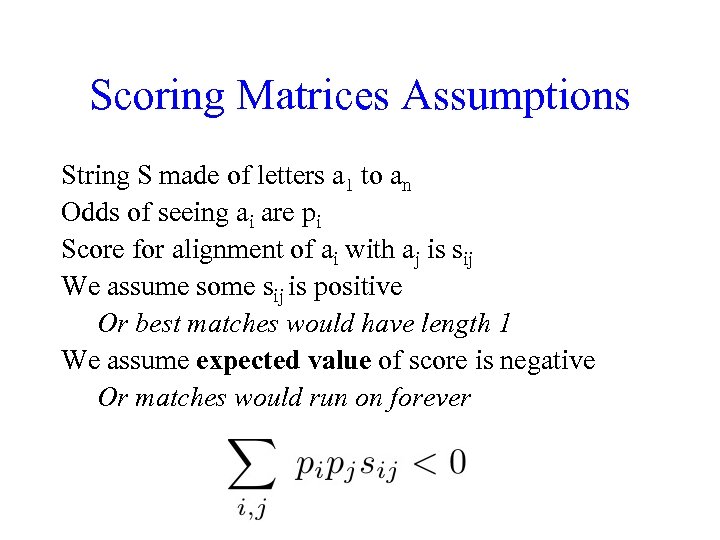

Scoring Matrices Let's make some assumptions about scores Additive – for ease of computation Positive is good Negative is bad Next slide: Must have at least one positive score Expected score must be negative

Scoring Matrices Assumptions String S made of letters a 1 to an Odds of seeing ai are pi Score for alignment of ai with aj is sij We assume some sij is positive Or best matches would have length 1 We assume expected value of score is negative Or matches would run on forever

Scoring Matrices Assumptions String S made of letters a 1 to an Odds of seeing ai are pi Score for alignment of ai with aj is sij We assume some sij is positive We assume expected value of score is negative How to compare scores from different matrices? Are matches from 2 M twice those from M? We will find a way to normalize a matrix

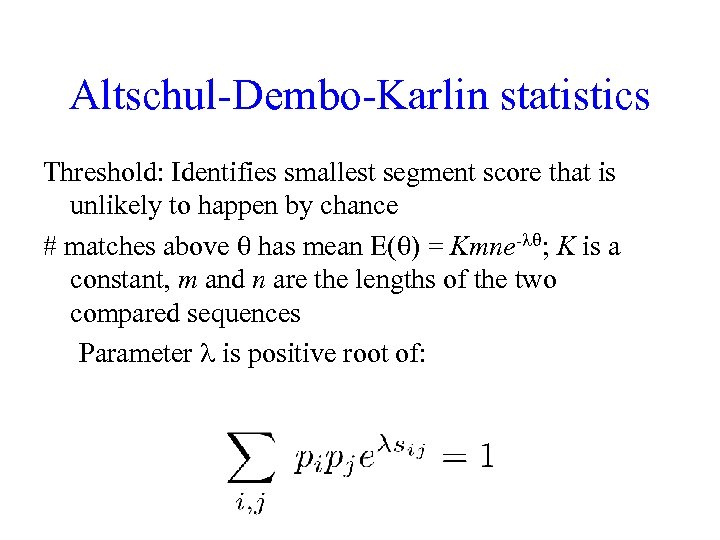

Altschul-Dembo-Karlin statistics Threshold: Identifies smallest segment score that is unlikely to happen by chance # matches above q has mean E(q) = Kmne-lq; K is a constant, m and n are the lengths of the two compared sequences Parameter l is positive root of:

Background Frequency Some residues appear more often than others Notation: pi is probability of ith residue We may compute genome wide frequency We could also look at local frequency Let qij represent the odds of aligning ith with jth Should we give a high score or a low score when aligning with a rare residue?

Assumptions Should have at least one positive entry, or best scores will have length 1 Expected value of a score (aka Average score) should be negative, or we will tend to have very long matches Entries in scoring matrix should look like this

Why log? Probabilities should be multiplied P(AB) = P(A)P(B) Odds of match in first place times odds of match in second place… But we want to get a score by adding Log turns products into sums

PAM - (Dayhoff et al. , 1978) Original substitution matrix Compare closely related species Use Global Alignment Point Accepted Mutation 1 PAM = PAM 1 = 1% average change of all amino acid positions After 100 PAMs of evolution, not every residue will have changed Some residues may have mutated several times Some residues may have returned to their original state Some residues may not changed at all

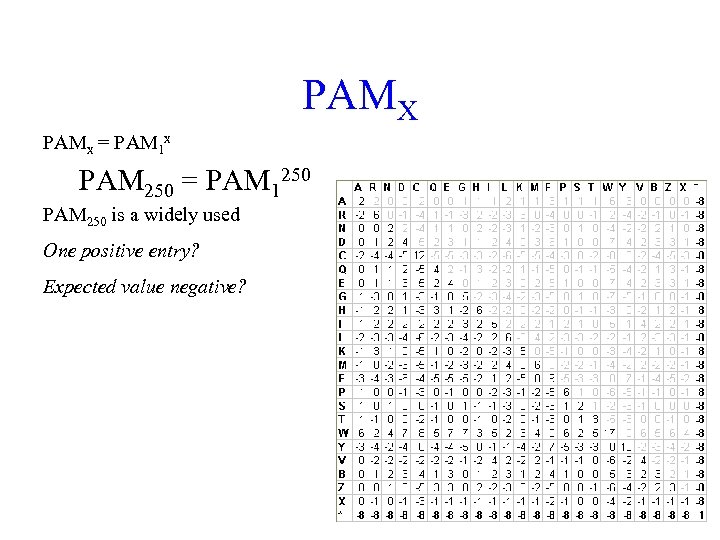

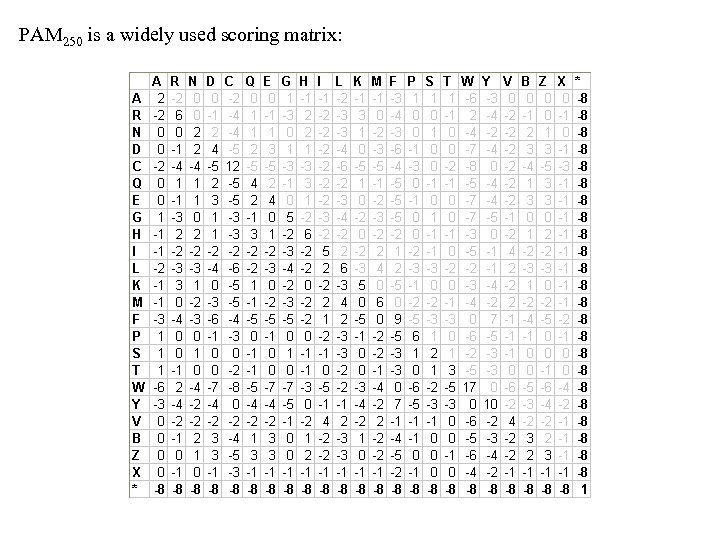

PAMX PAMx = PAM 1 x PAM 250 = PAM 1250 PAM 250 is a widely used One positive entry? Expected value negative?

PAM 250 is a widely used scoring matrix:

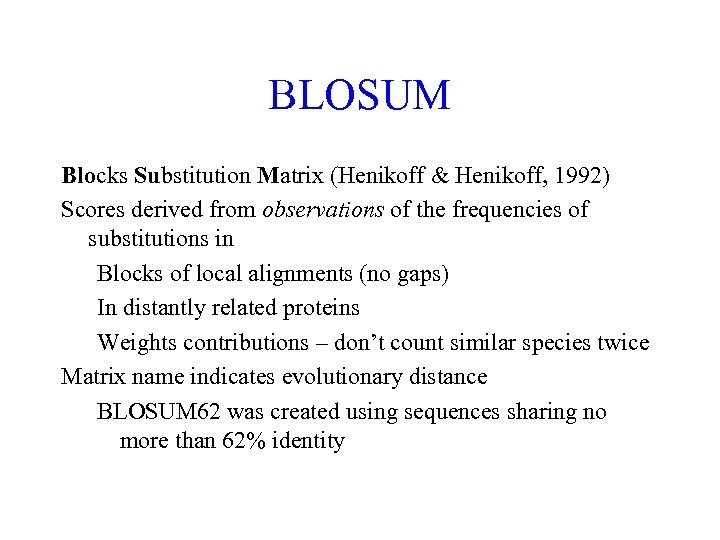

BLOSUM Blocks Substitution Matrix (Henikoff & Henikoff, 1992) Scores derived from observations of the frequencies of substitutions in Blocks of local alignments (no gaps) In distantly related proteins Weights contributions – don’t count similar species twice Matrix name indicates evolutionary distance BLOSUM 62 was created using sequences sharing no more than 62% identity

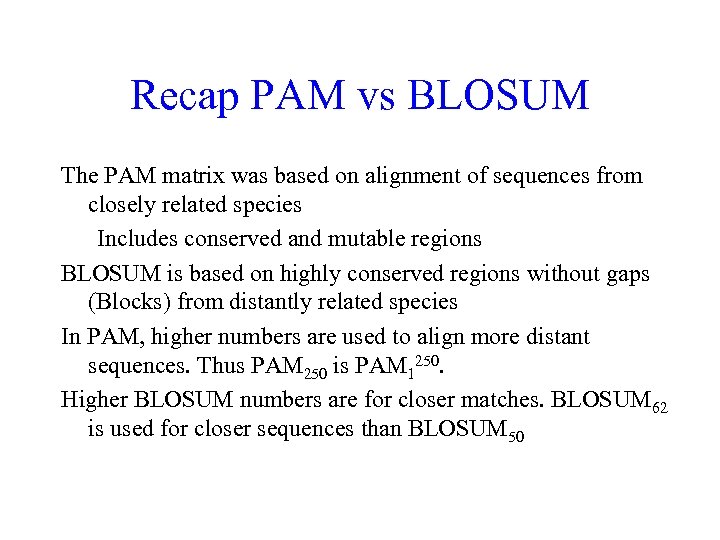

Recap PAM vs BLOSUM The PAM matrix was based on alignment of sequences from closely related species Includes conserved and mutable regions BLOSUM is based on highly conserved regions without gaps (Blocks) from distantly related species In PAM, higher numbers are used to align more distant sequences. Thus PAM 250 is PAM 1250. Higher BLOSUM numbers are for closer matches. BLOSUM 62 is used for closer sequences than BLOSUM 50

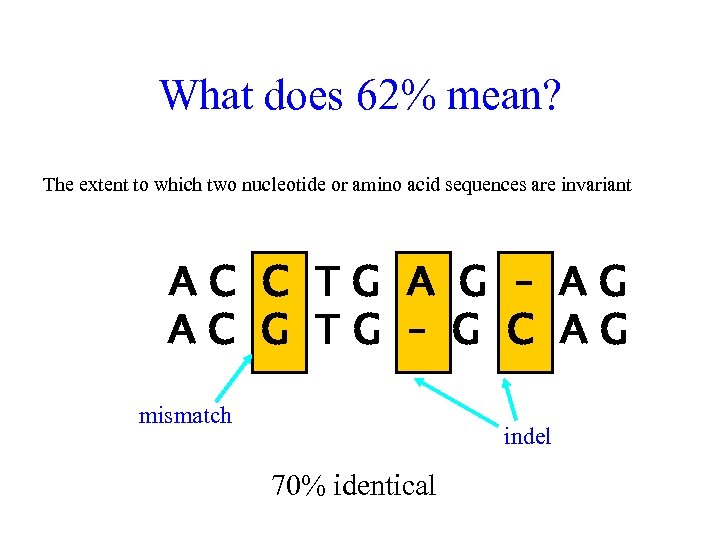

What does 62% mean? The extent to which two nucleotide or amino acid sequences are invariant AC C TG A G – AG AC G TG – G C AG mismatch indel 70% identical

The Blosum 50 Scoring Matrix One positive entry? Expected value negative?

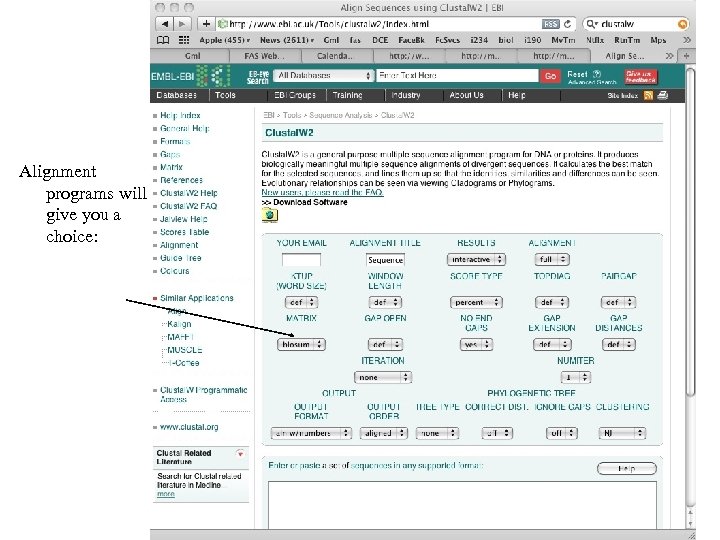

How do we use these? Alignment programs will give you a choice:

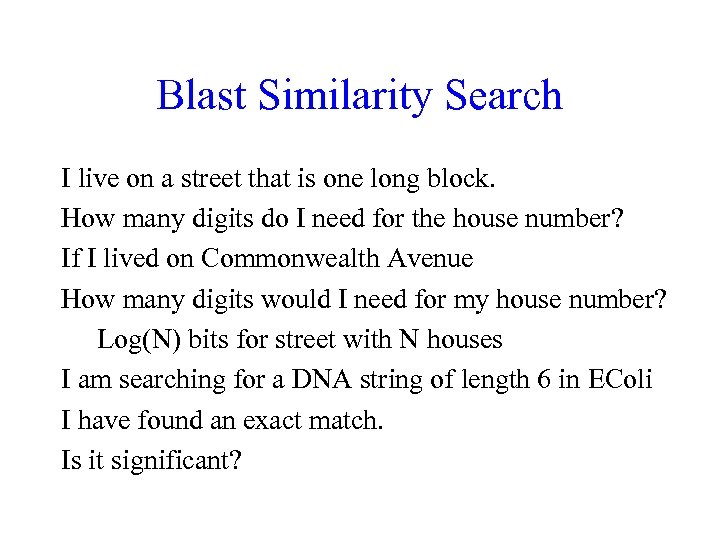

Blast Similarity Search I live on a street that is one long block. How many digits do I need for the house number? If I lived on Commonwealth Avenue How many digits would I need for my house number? Log(N) bits for street with N houses I am searching for a DNA string of length 6 in EColi I have found an exact match. Is it significant?

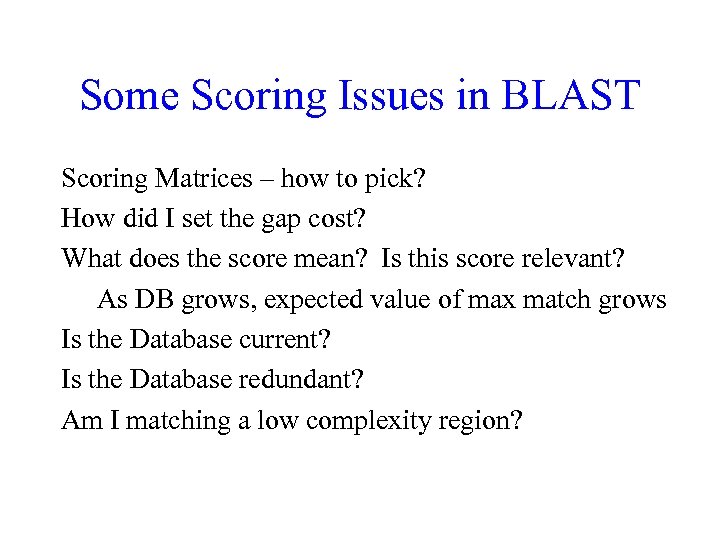

Some Scoring Issues in BLAST Scoring Matrices – how to pick? How did I set the gap cost? What does the score mean? Is this score relevant? As DB grows, expected value of max match grows Is the Database current? Is the Database redundant? Am I matching a low complexity region?

Outline Homework Introduce Scoring Matrices Some mismatches are better than others Solve Alignment with Affine Gap Penalties Continuing deletion more common than starting one Linear Space Alignment Multiple Alignment

Gap Penalties Currently, a fixed penalty σ is given to every indel: -σ for 1 indel, -2σ for 2 consecutive indels -3σ for 3 consecutive indels, etc. This is called a "linear gap penalty" Linear in the size of the gap Too severe penalty for a series of 100 consecutive indels

Affine Gap Penalties In nature, a series of k indels often come as a single event rather than a series of k single nucleotide events Our current scoring gives same score for both alignments This is more likely. This is less likely.

Accounting for Gaps- contiguous sequence of spaces in one of the rows Score for a gap of length x is: -(ρ + σx) where ρ >0 is the penalty for introducing a gap: gap opening penalty ρ will be large relative to σ: gap extension penalty Don't add as much of a penalty for extending the gap.

Affine Transformation Linear Transformation

Affine Gap Penalties Gap penalties: -ρ-σ when there is 1 indel -ρ-2σ when there are 2 indels in a row -ρ-3σ when there are 3 indels in a row, etc. -ρ- x·σ (-gap opening - x gap extensions) New penalties for runs of horizontal or vertical edges

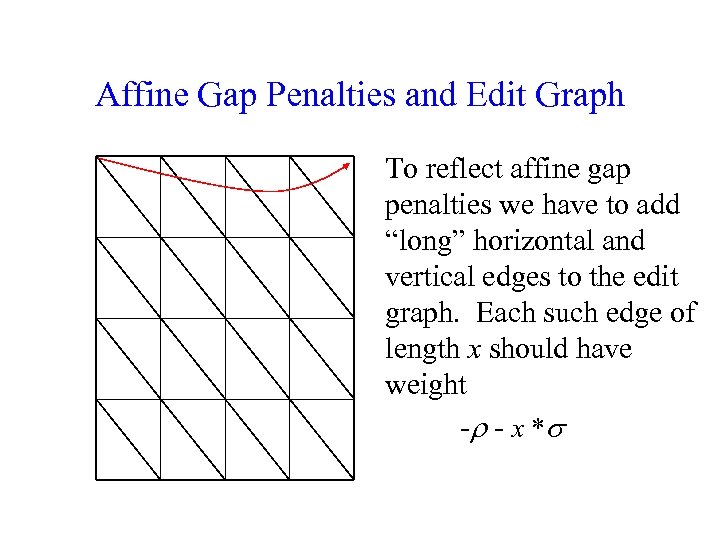

Affine Gap Penalties and Edit Graph To reflect affine gap penalties we have to add “long” horizontal and vertical edges to the edit graph. Each such edge of length x should have weight - - x *

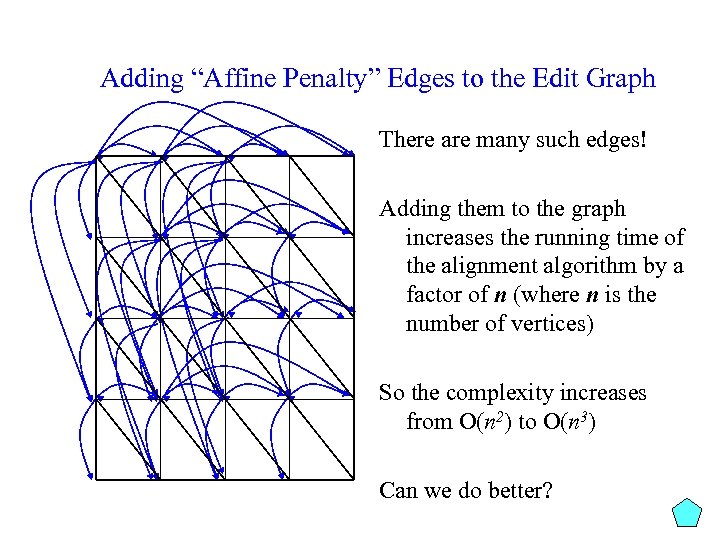

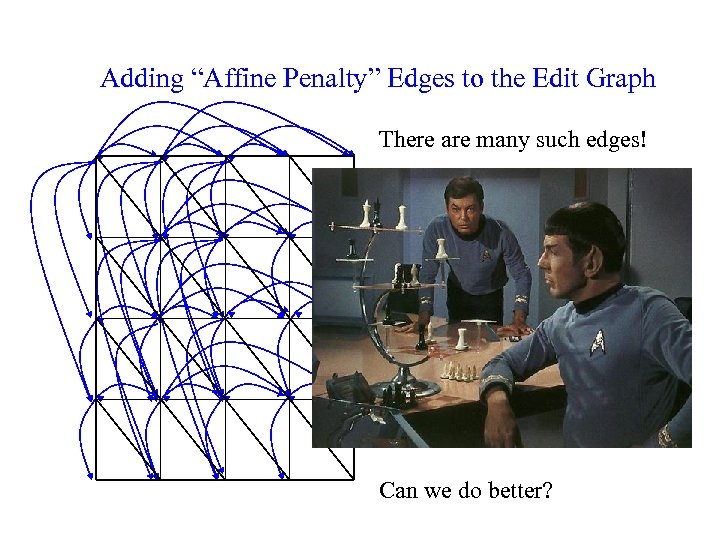

Adding “Affine Penalty” Edges to the Edit Graph There are many such edges! Adding them to the graph increases the running time of the alignment algorithm by a factor of n (where n is the number of vertices) So the complexity increases from O(n 2) to O(n 3) Can we do better?

Adding “Affine Penalty” Edges to the Edit Graph There are many such edges! Adding them to the graph increases the running time of the alignment algorithm by a factor of n (where n is the number of vertices) So the complexity increases from O(n 2) to O(n 3) Can we do better?

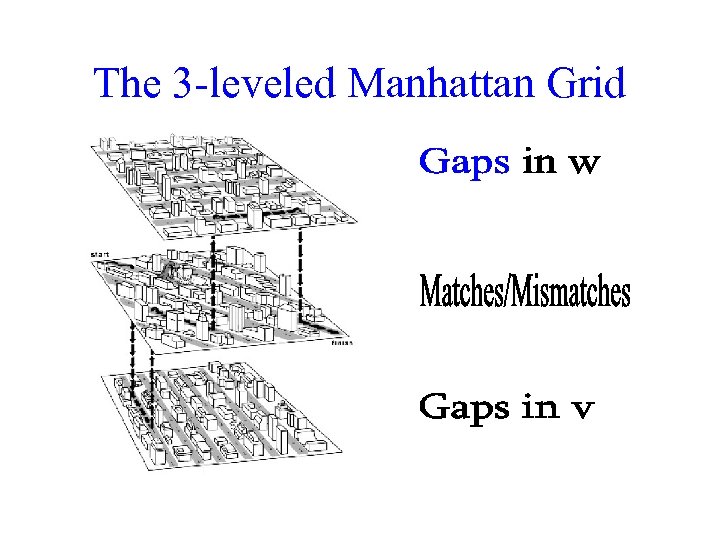

The 3 -leveled Manhattan Grid

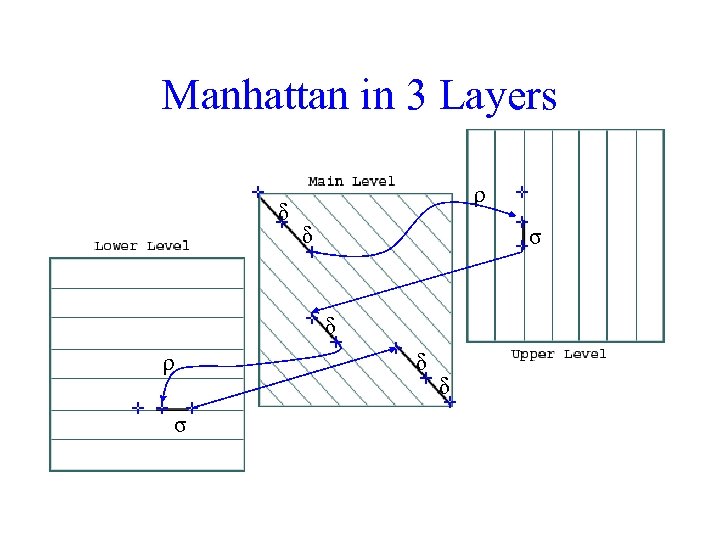

Manhattan in 3 Layers δ ρ δ σ δ ρ σ δ δ

Switching between 3 Layers Levels: The main level is for diagonal edges The lower level is for horizontal edges The upper level is for vertical edges A jumping penalty is assigned to moving from the main level to either the upper level or the lower level (- ) There is a gap extension penalty for each continuation on a level other than the main level (- )

Affine Gap Penalties and 3 Layer Manhattan Grid The three recurrences for the scoring algorithm creates a 3 -layered graph. The top level creates/extends gaps in the sequence w. The bottom level creates/extends gaps in sequence v. The middle level extends matches and mismatches.

Affine Gap Penalties and 3 Layer Manhattan Grid The three recurrences for the scoring algorithm creates a 3 -layered graph. The top level creates/extends gaps in the sequence w. The bottom level creates/extends gaps in sequence v. The middle level extends matches and mismatches. As stated, no way to get from insertion to deletion

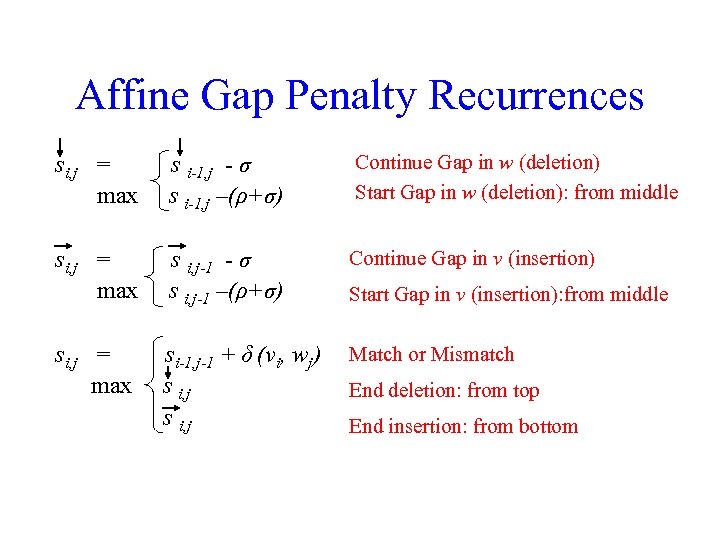

Affine Gap Penalty Recurrences si, j = max s i-1, j - σ s i-1, j –(ρ+σ) Continue Gap in w (deletion) Start Gap in w (deletion): from middle si, j = max s i, j-1 - σ s i, j-1 –(ρ+σ) Continue Gap in v (insertion) si, j = max si-1, j-1 + δ (vi, wj) s i, j Match or Mismatch Start Gap in v (insertion): from middle End deletion: from top End insertion: from bottom

Outline Homework Introduce Scoring Matrices Some mismatches are better than others Solve Alignment with Affine Gap Penalties Continuing deletion more common than starting one Linear Space Alignment Multiple Alignment

95 95 Divide and Conquer is a general strategy Take a difficult problem and decompose it into two parts

96 Search for 6 How long would it take to find 6 in the list below? 5 8 3 2 5 9 0 6 1 5 8

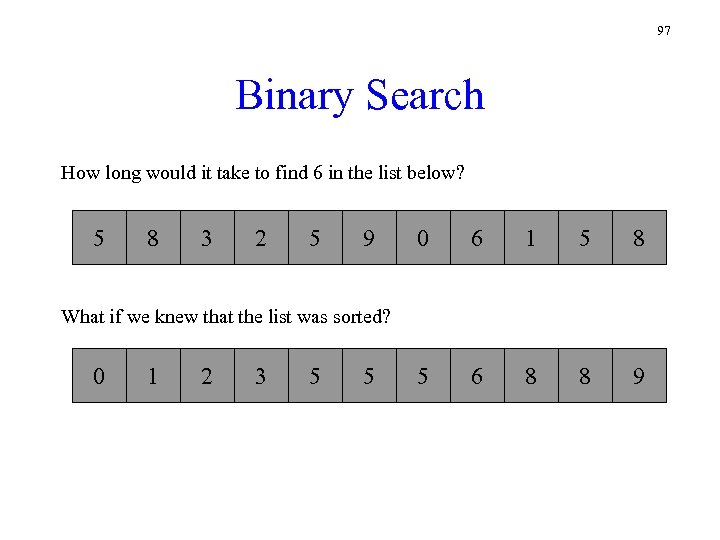

97 Binary Search How long would it take to find 6 in the list below? 5 8 3 2 5 9 0 6 1 5 8 5 6 8 8 9 What if we knew that the list was sorted? 0 1 2 3 5 5

![98 98 Finding a root [0, 2] - midpoint is 1 f(1) = 1 98 98 Finding a root [0, 2] - midpoint is 1 f(1) = 1](https://present5.com/presentation/330e1972ab21be1a983b31aaa2183faf/image-98.jpg)

98 98 Finding a root [0, 2] - midpoint is 1 f(1) = 1 - 2 = -1, so interval [0, 1] is below axis, [1, 2] must cross [1, 2] - midpoint is 3/2 f(3/2) = 9/4 - 2 = 1/4, so curve crosses in region [1, 3/2] [1, 1. 5] - midpoint is 5/4 f(5/4) = 25/16 - 32/16 < 0, so curve crosses in region [1. 25, 1. 5] …. At each stage of this process, we halve the interval: needs about 3 iterations per digit. At each point, we halve the region holding the solution

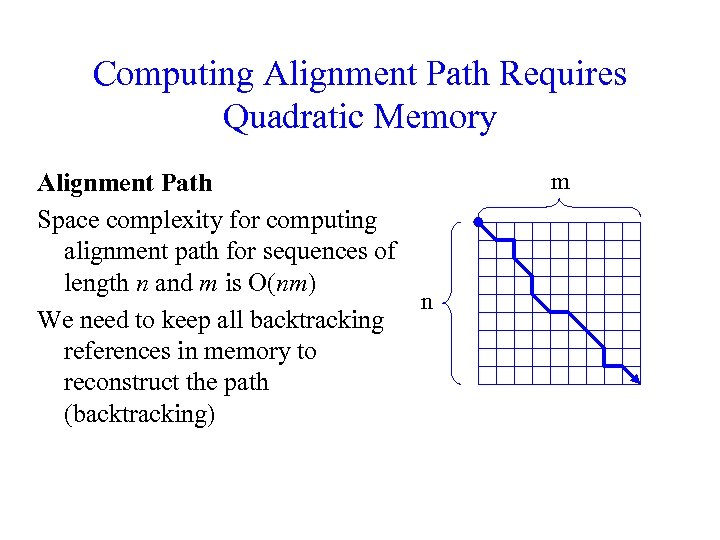

Computing Alignment Path Requires Quadratic Memory Alignment Path Space complexity for computing alignment path for sequences of length n and m is O(nm) n We need to keep all backtracking references in memory to reconstruct the path (backtracking) m

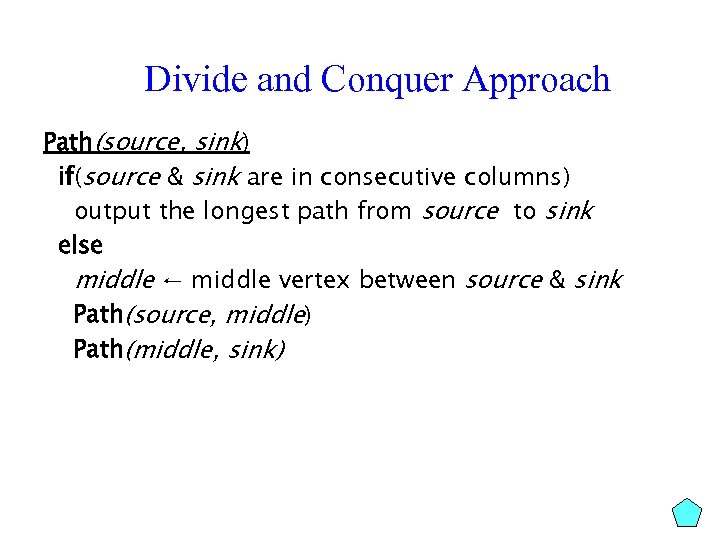

Divide and Conquer Approach Path(source, sink) if(source & sink are in consecutive columns) output the longest path from source to sink else middle ← middle vertex between source & sink Path(source, middle) Path(middle, sink)

Divide and Conquer Approach to LCS Path(source, sink) if(source & sink are in consecutive columns) output the longest path from source to sink else middle ← middle vertex between source & sink Path(source, middle) Path(middle, sink) The only problem left is how to find this “middle vertex”!

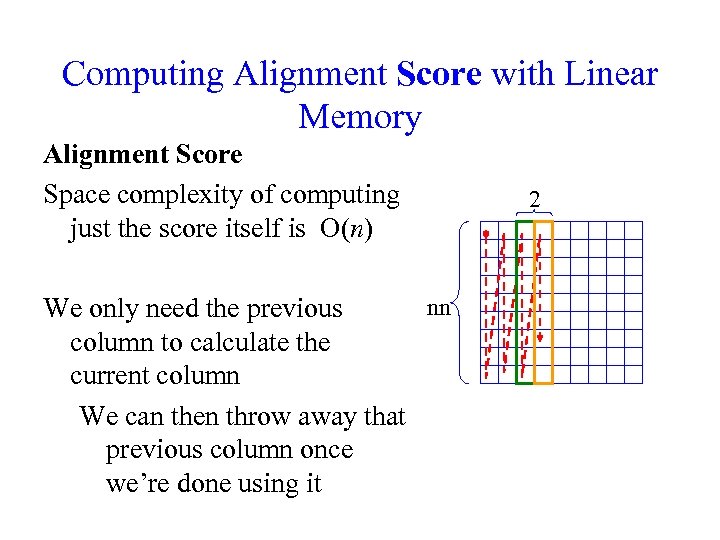

Computing Alignment Score with Linear Memory Alignment Score Space complexity of computing just the score itself is O(n) nn We only need the previous column to calculate the current column We can then throw away that previous column once we’re done using it 2

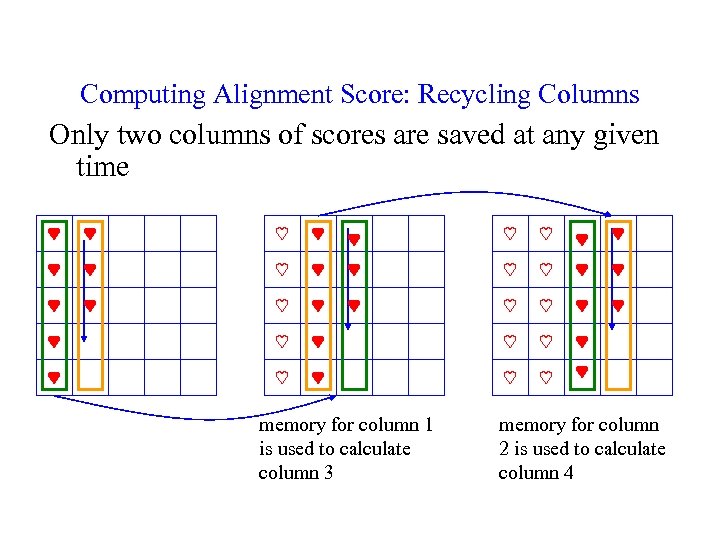

Computing Alignment Score: Recycling Columns Only two columns of scores are saved at any given time memory for column 1 is used to calculate column 3 memory for column 2 is used to calculate column 4

Computing Alignment Score with Linear Memory Alignment Score Space complexity of computing just the score itself is O(n) Only need the previous column to calculate the current column nn This computes the global score Does not remember how we got here 2

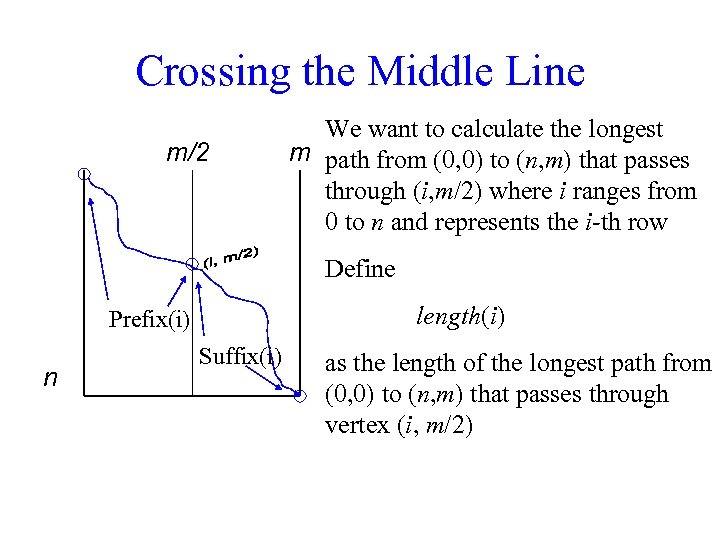

Crossing the Middle Line m/2 We want to calculate the longest m path from (0, 0) to (n, m) that passes through (i, m/2) where i ranges from 0 to n and represents the i-th row Define length(i) Prefix(i) n Suffix(i) as the length of the longest path from (0, 0) to (n, m) that passes through vertex (i, m/2)

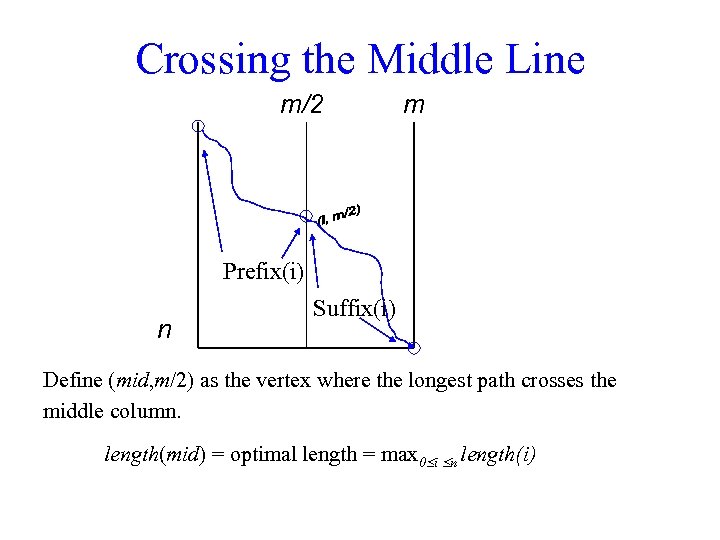

Crossing the Middle Line m/2 m Prefix(i) n Suffix(i) Define (mid, m/2) as the vertex where the longest path crosses the middle column. length(mid) = optimal length = max 0 i n length(i)

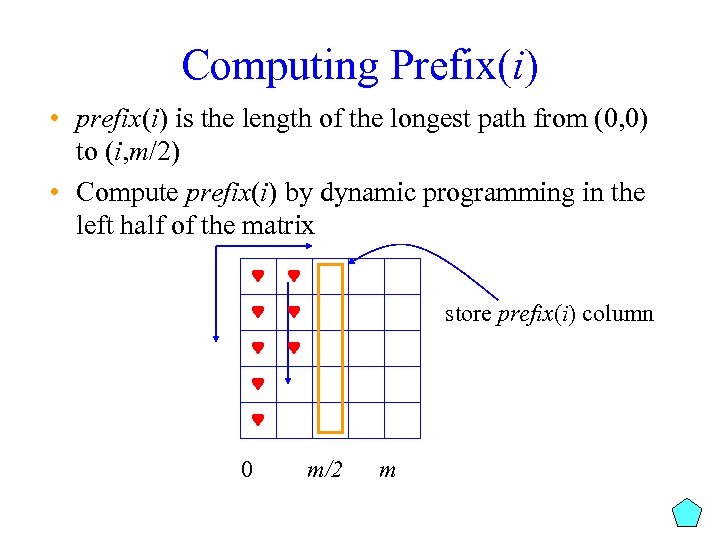

Computing Prefix(i) • prefix(i) is the length of the longest path from (0, 0) to (i, m/2) • Compute prefix(i) by dynamic programming in the left half of the matrix store prefix(i) column 0 m/2 m

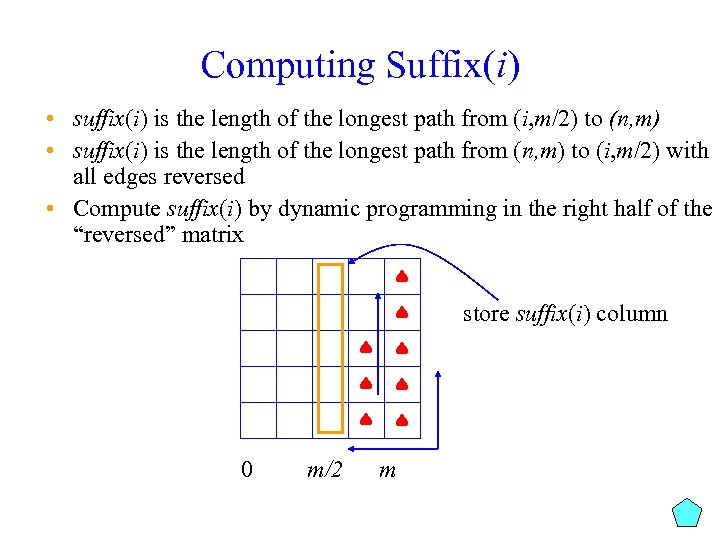

Computing Suffix(i) • suffix(i) is the length of the longest path from (i, m/2) to (n, m) • suffix(i) is the length of the longest path from (n, m) to (i, m/2) with all edges reversed • Compute suffix(i) by dynamic programming in the right half of the “reversed” matrix store suffix(i) column 0 m/2 m

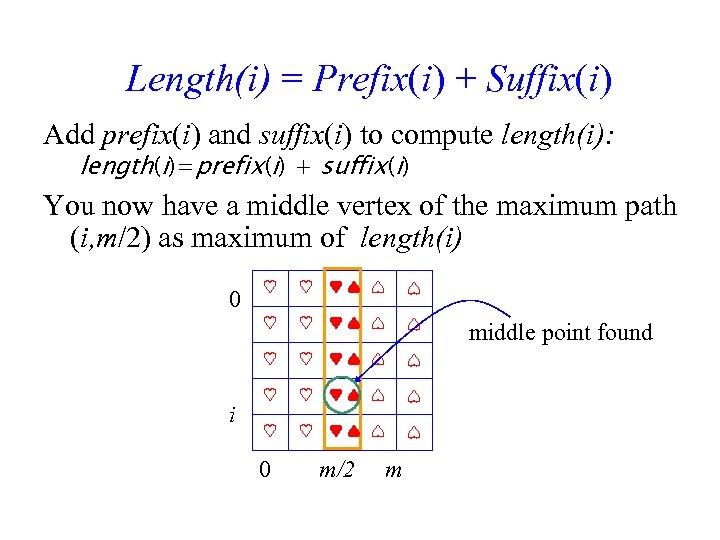

Length(i) = Prefix(i) + Suffix(i) Add prefix(i) and suffix(i) to compute length(i): length(i)=prefix(i) + suffix(i) You now have a middle vertex of the maximum path (i, m/2) as maximum of length(i) 0 middle point found i 0 m/2 m

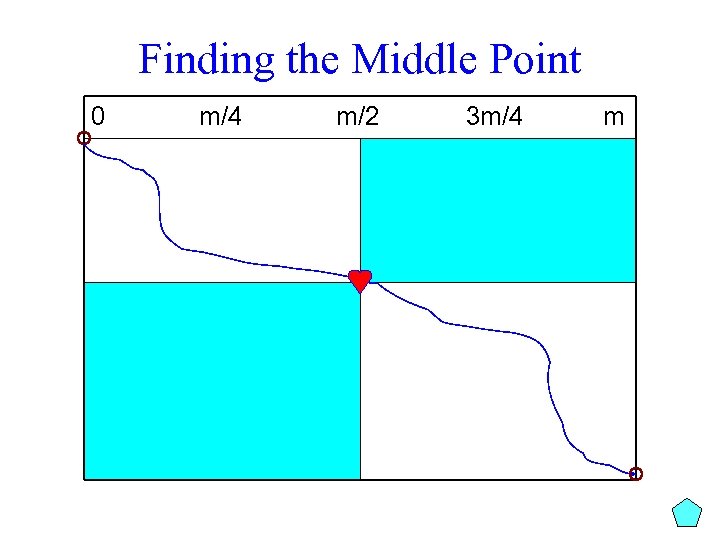

Finding the Middle Point 0 m/4 m/2 3 m/4 m

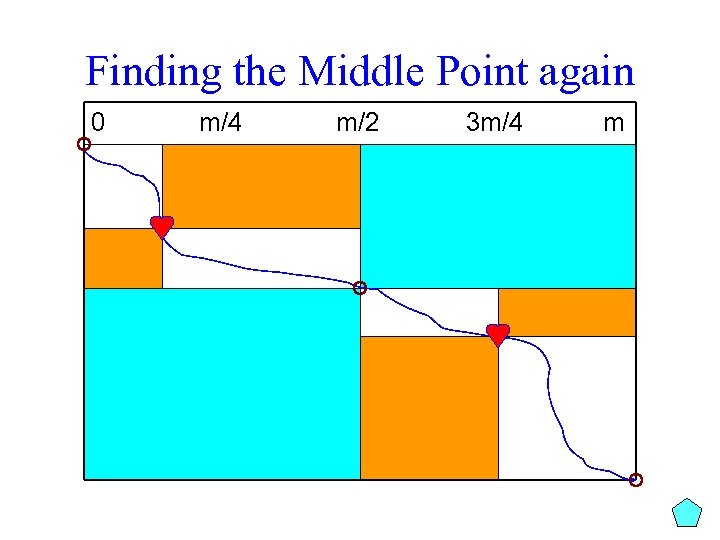

Finding the Middle Point again 0 m/4 m/2 3 m/4 m

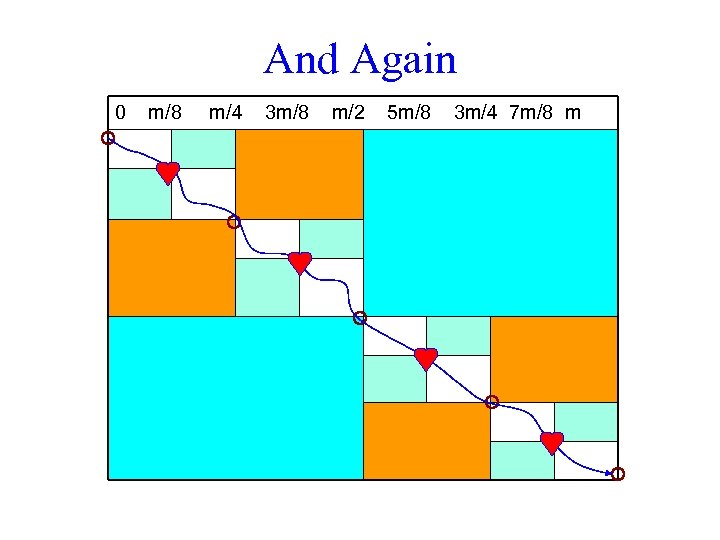

And Again 0 m/8 m/4 3 m/8 m/2 5 m/8 3 m/4 7 m/8 m

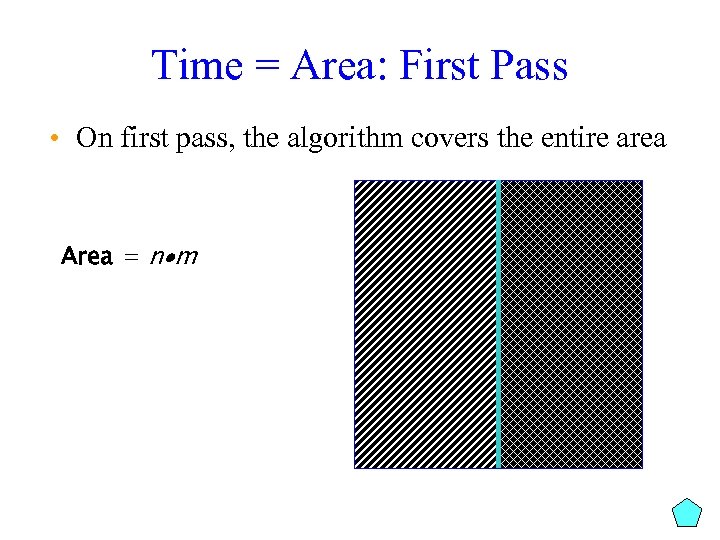

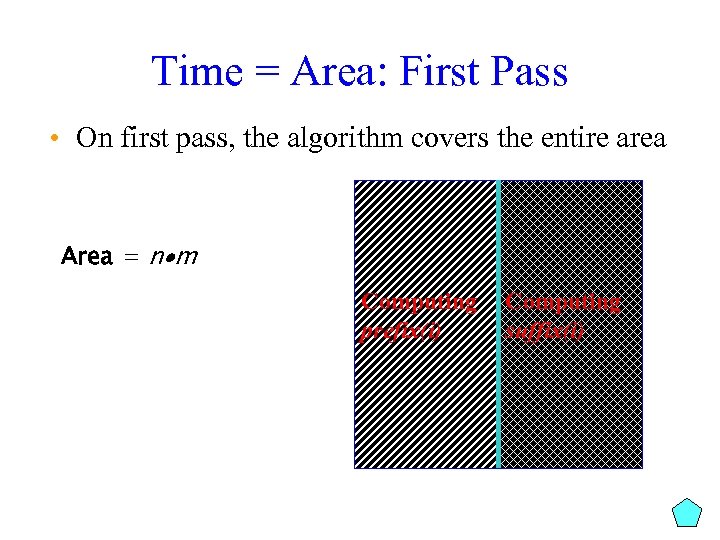

Time = Area: First Pass • On first pass, the algorithm covers the entire area Area = n m

Time = Area: First Pass • On first pass, the algorithm covers the entire area Area = n m Computing prefix(i) Computing suffix(i)

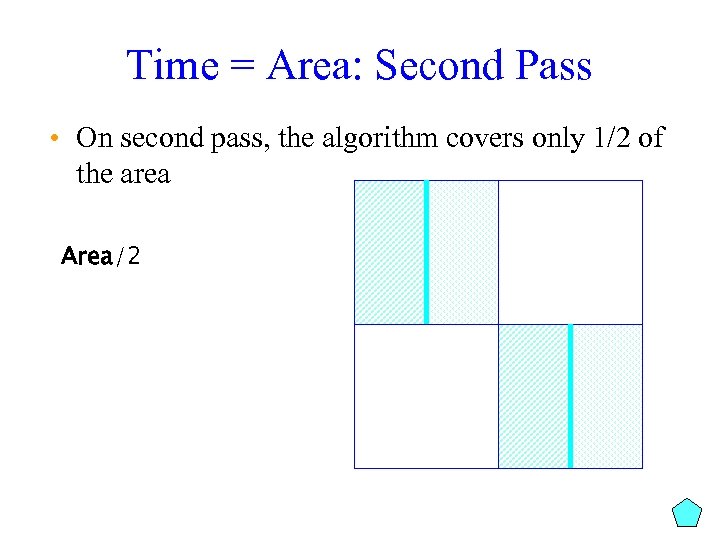

Time = Area: Second Pass • On second pass, the algorithm covers only 1/2 of the area Area/2

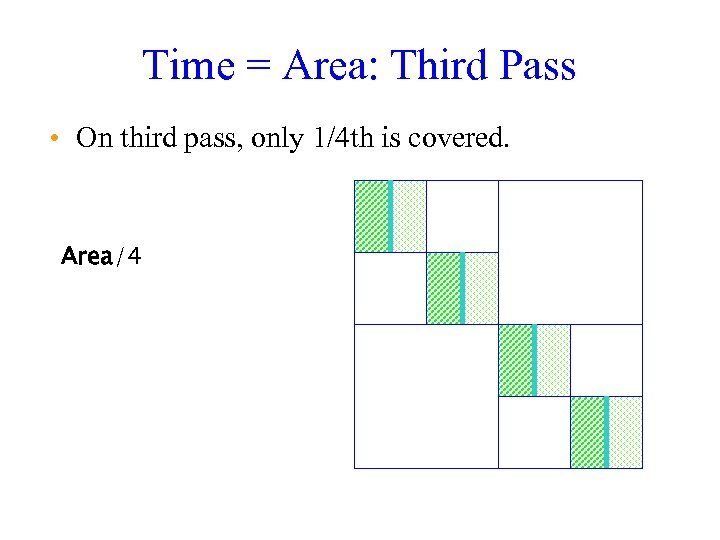

Time = Area: Third Pass • On third pass, only 1/4 th is covered. Area/4

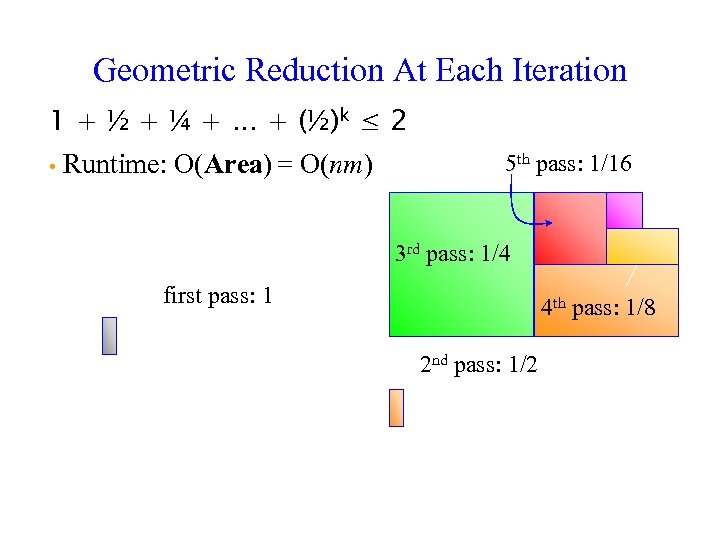

Geometric Reduction At Each Iteration 1 + ½ + ¼ +. . . + (½)k ≤ 2 • Runtime: O(Area) = O(nm) 5 th pass: 1/16 3 rd pass: 1/4 first pass: 1 4 th pass: 1/8 2 nd pass: 1/2

Outline Homework Introduce Scoring Matrices Some mismatches are better than others Solve Alignment with Affine Gap Penalties Continuing deletion more common than starting one Linear Space Alignment Multiple Alignment

Multiple Alignment Dynamic Programming in 3 -D Progressive Alignment Profile Progressive Alignment (Clustal. W) Scoring Multiple Alignments Entropy Sum of Pairs Alignment Partial Order Alignment (POA) A-Bruijin (ABA) Approach to Multiple Alignment

Generalizing Pairwise Alignment Multiple alignments can reveal subtle similarities that pairwise alignments do not reveal Alignment of 2 sequences represented as a 2 -row matrix Represent alignment of 3 sequences as a 3 -row matrix A T _ G C G _ A _ C G T _ A A T C A C _ A Score: more conserved columns, better alignment

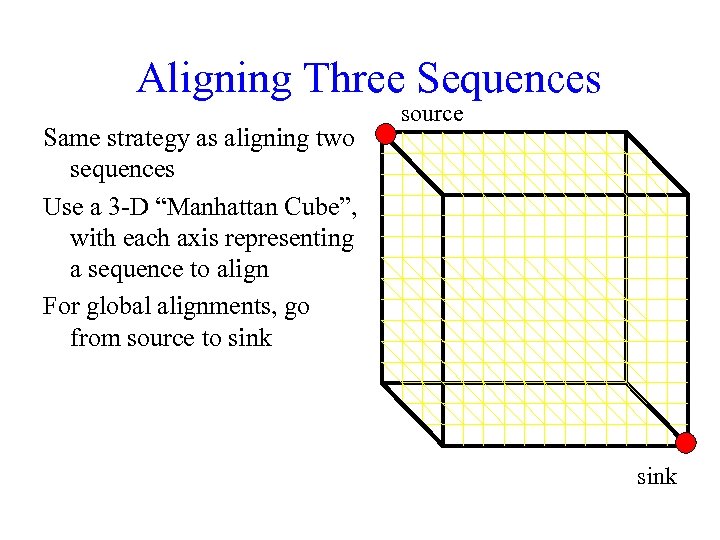

Aligning Three Sequences Same strategy as aligning two sequences Use a 3 -D “Manhattan Cube”, with each axis representing a sequence to align For global alignments, go from source to sink source sink

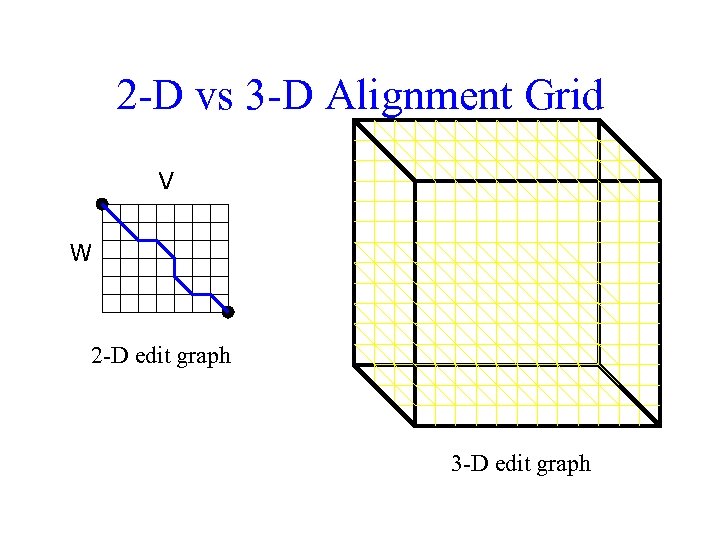

2 -D vs 3 -D Alignment Grid V W 2 -D edit graph 3 -D edit graph

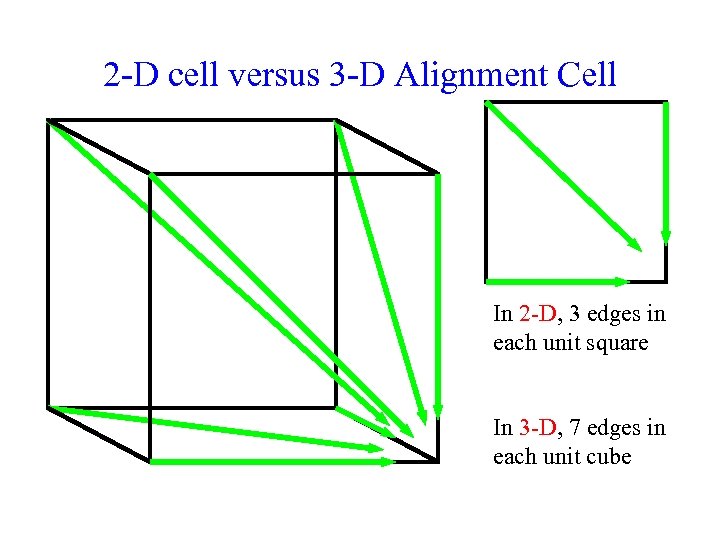

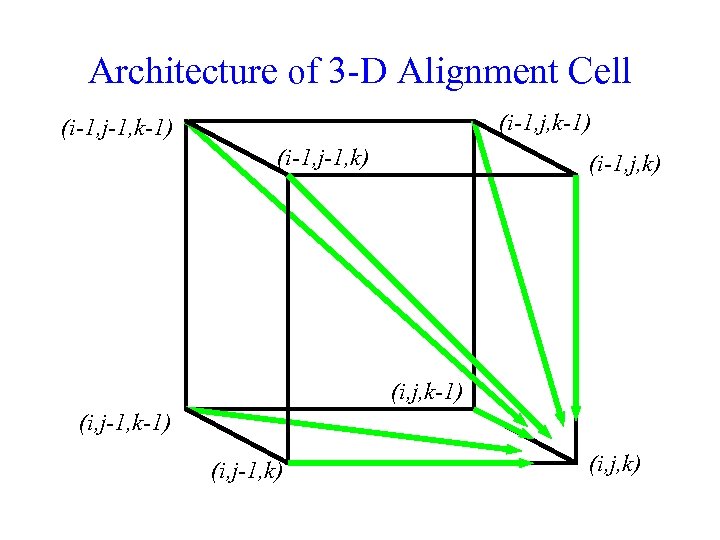

2 -D cell versus 3 -D Alignment Cell In 2 -D, 3 edges in each unit square In 3 -D, 7 edges in each unit cube

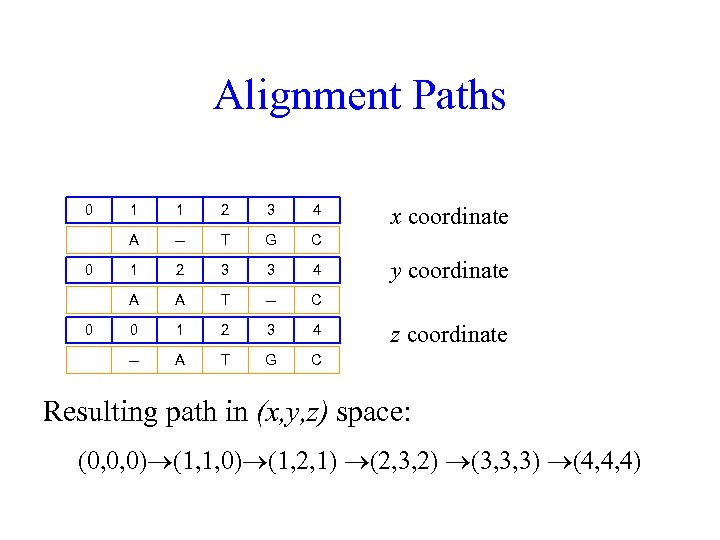

Alignment Paths 0 2 3 4 -- T G C 1 2 3 3 4 A A T -- C 0 1 2 3 4 -- 0 1 A T G C x coordinate y coordinate z coordinate Resulting path in (x, y, z) space: (0, 0, 0) (1, 1, 0) (1, 2, 1) (2, 3, 2) (3, 3, 3) (4, 4, 4)

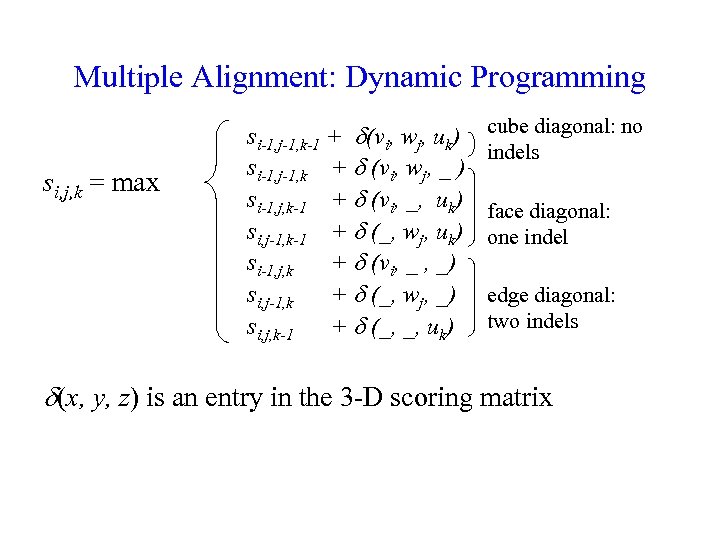

Multiple Alignment: Dynamic Programming si, j, k = max si-1, j-1, k-1 + (vi, wj, uk) si-1, j-1, k + (vi, wj, _ ) si-1, j, k-1 + (vi, _, uk) si, j-1, k-1 + (_, wj, uk) si-1, j, k + (vi, _ , _) si, j-1, k + (_, wj, _) si, j, k-1 + (_, _, uk) cube diagonal: no indels face diagonal: one indel edge diagonal: two indels (x, y, z) is an entry in the 3 -D scoring matrix

Architecture of 3 -D Alignment Cell (i-1, j, k-1) (i-1, j-1, k) (i-1, j, k) (i, j, k-1) (i, j-1, k) (i, j, k)

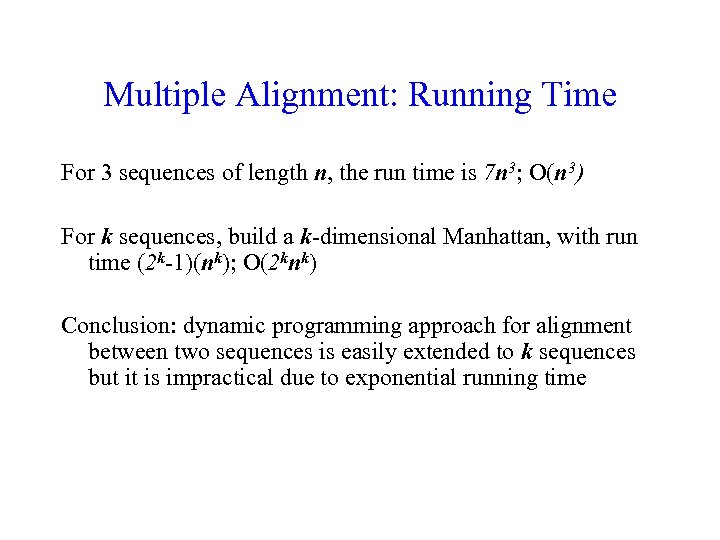

Multiple Alignment: Running Time For 3 sequences of length n, the run time is 7 n 3; O(n 3) For k sequences, build a k-dimensional Manhattan, with run time (2 k-1)(nk); O(2 knk) Conclusion: dynamic programming approach for alignment between two sequences is easily extended to k sequences but it is impractical due to exponential running time

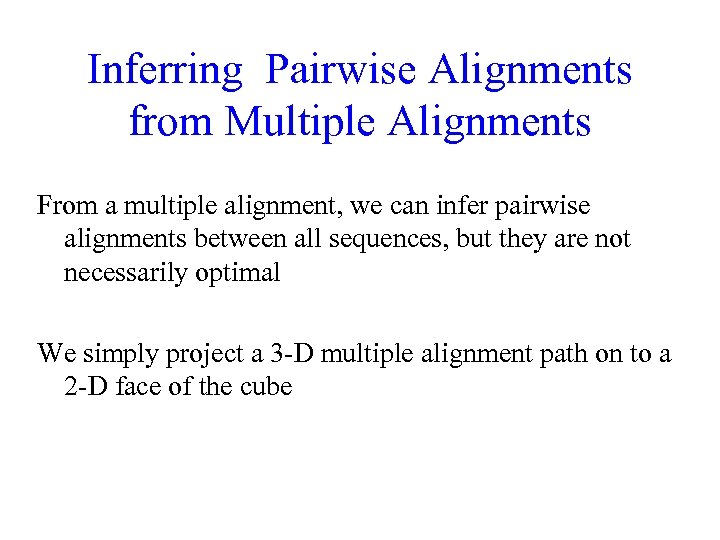

Inferring Pairwise Alignments from Multiple Alignments From a multiple alignment, we can infer pairwise alignments between all sequences, but they are not necessarily optimal We simply project a 3 -D multiple alignment path on to a 2 -D face of the cube

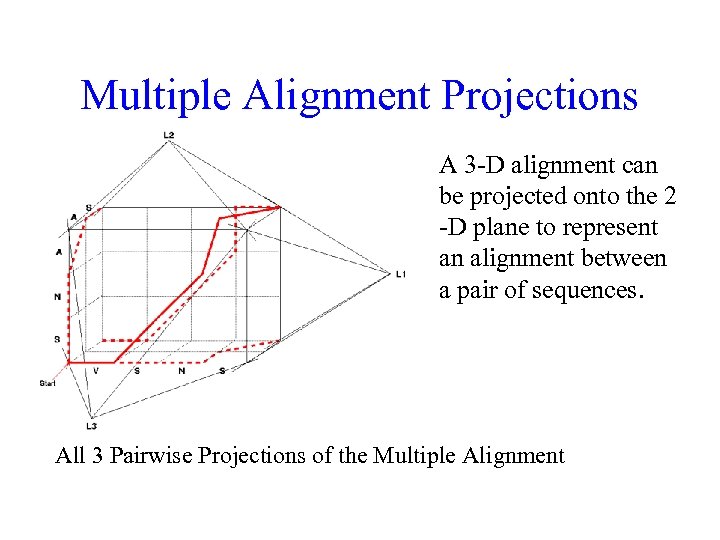

Multiple Alignment Projections A 3 -D alignment can be projected onto the 2 -D plane to represent an alignment between a pair of sequences. All 3 Pairwise Projections of the Multiple Alignment

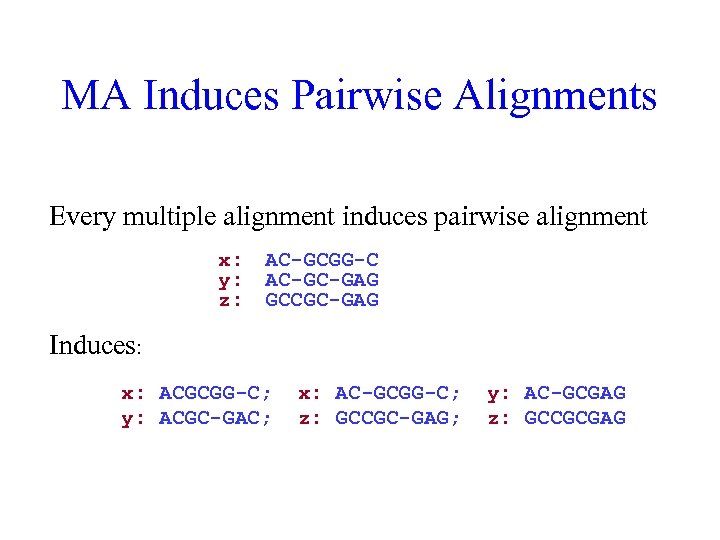

MA Induces Pairwise Alignments Every multiple alignment induces pairwise alignment x: y: z: AC-GCGG-C AC-GC-GAG GCCGC-GAG Induces: x: ACGCGG-C; y: ACGC-GAC; x: AC-GCGG-C; z: GCCGC-GAG; y: AC-GCGAG z: GCCGCGAG

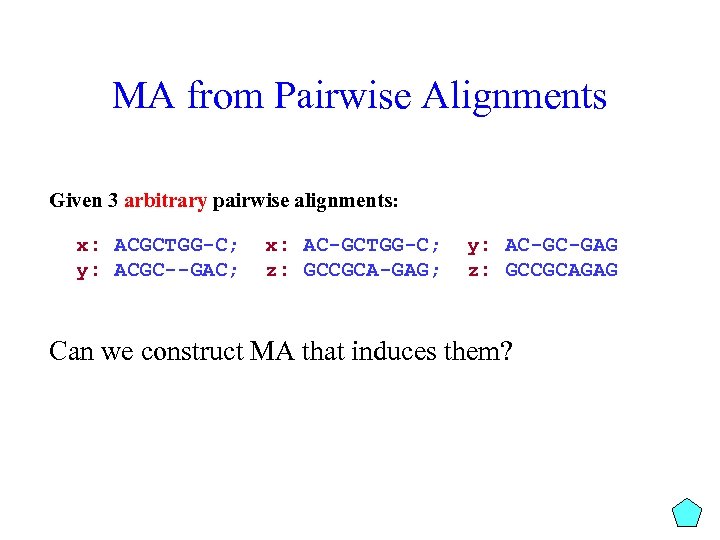

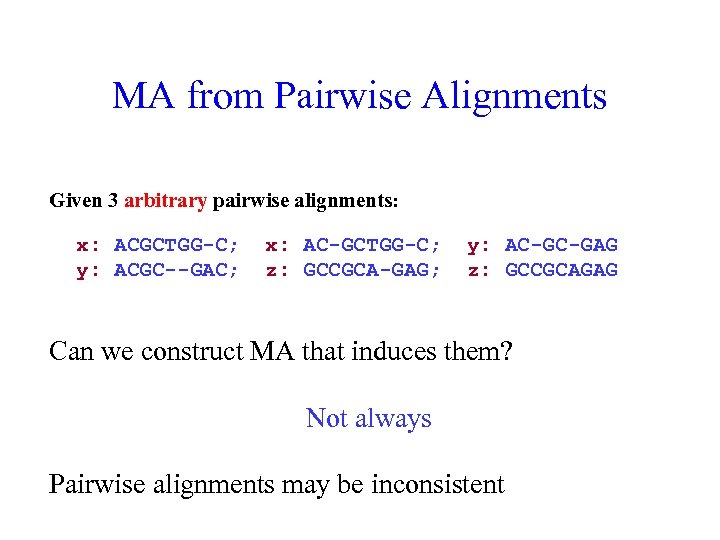

MA from Pairwise Alignments Given 3 arbitrary pairwise alignments: x: ACGCTGG-C; y: ACGC--GAC; x: AC-GCTGG-C; z: GCCGCA-GAG; y: AC-GC-GAG z: GCCGCAGAG Can we construct MA that induces them?

MA from Pairwise Alignments Given 3 arbitrary pairwise alignments: x: ACGCTGG-C; y: ACGC--GAC; x: AC-GCTGG-C; z: GCCGCA-GAG; y: AC-GC-GAG z: GCCGCAGAG Can we construct MA that induces them? Not always Pairwise alignments may be inconsistent

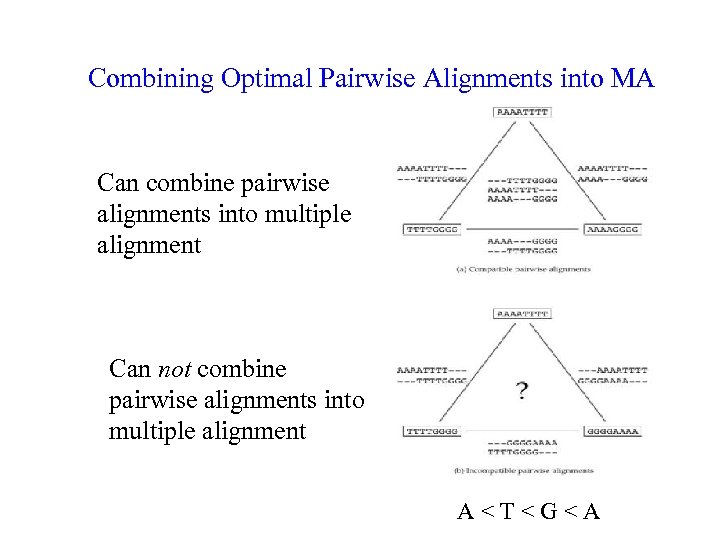

Combining Optimal Pairwise Alignments into MA Can combine pairwise alignments into multiple alignment Can not combine pairwise alignments into multiple alignment A<T<G<A

Inferring MA from Pairwise Alignments From an optimal multiple alignment, we can infer pairwise alignments between all pairs of sequences, but they are not necessarily optimal It is difficult to infer a ``good” multiple alignment from optimal pairwise alignments between all sequences

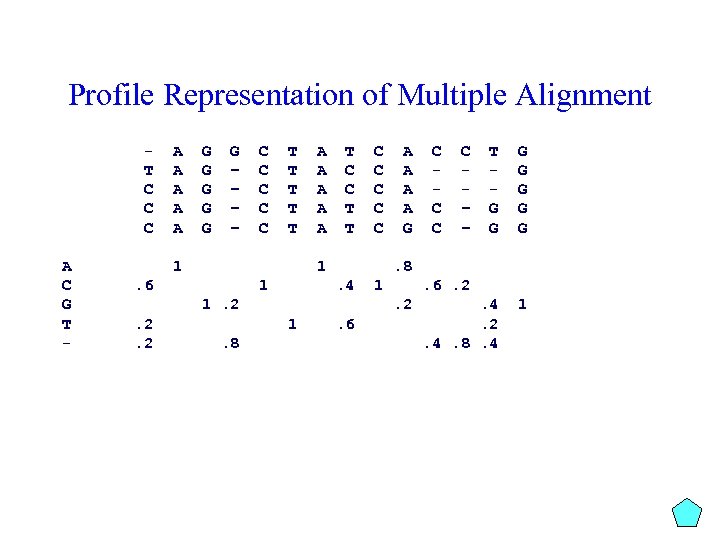

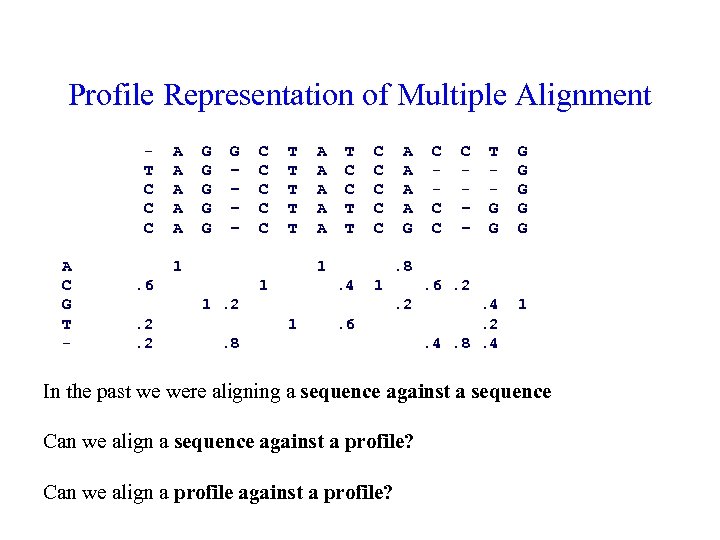

Profile Representation of Multiple Alignment T C C C A C G T - A A A G G G – – C C C T T T 1 A A A T C C T T 1 . 6 1 . 4 1 C C – – T G G G G . 4. 2. 4. 8. 4 1 . 6. 2. 2 1. 8 A A G. 8 1. 2. 2. 2 C C C . 6

Profile Representation of Multiple Alignment T C C C A C G T - A A A G G G – – C C C T T T 1 A A A T C C T T 1 . 6 1 A A G . 4 1 C – – T G G G G . 4. 2. 4. 8. 4 1 . 6. 2. 2 1 C C C . 8 1. 2. 2. 2 C C C . 6 . 8 In the past we were aligning a sequence against a sequence Can we align a sequence against a profile? Can we align a profile against a profile?

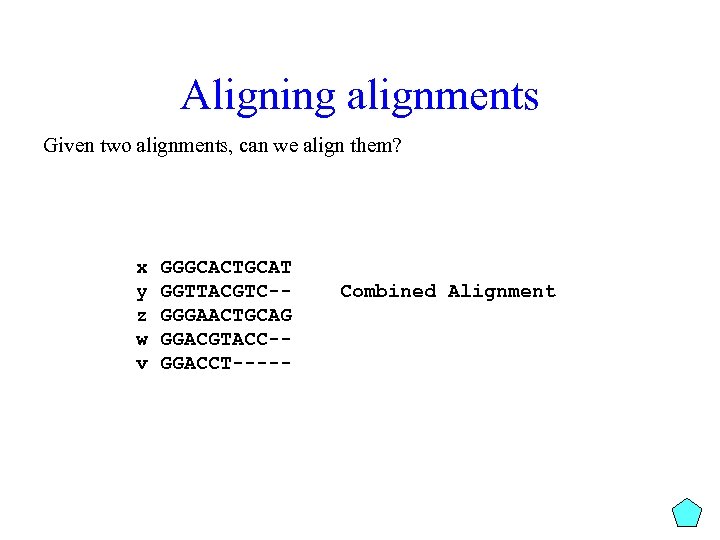

Aligning alignments Given two alignments, can we align them? x y z w v GGGCACTGCAT GGTTACGTC-GGGAACTGCAG GGACGTACC-GGACCT----- Combined Alignment

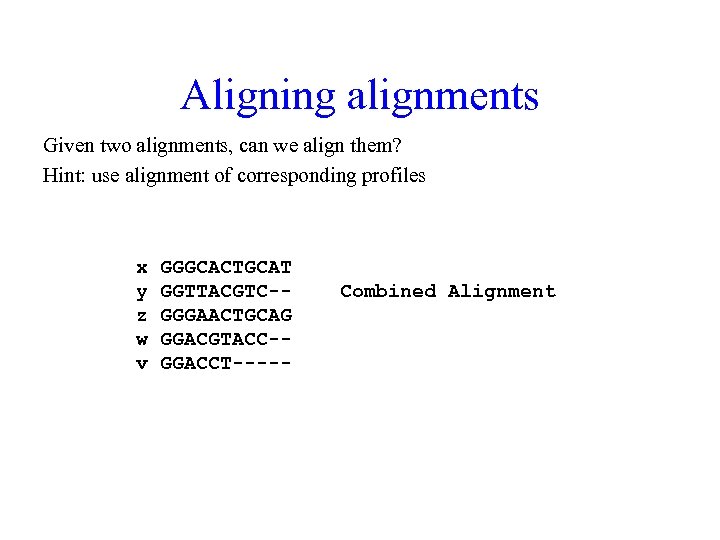

Aligning alignments Given two alignments, can we align them? Hint: use alignment of corresponding profiles x y z w v GGGCACTGCAT GGTTACGTC-GGGAACTGCAG GGACGTACC-GGACCT----- Combined Alignment

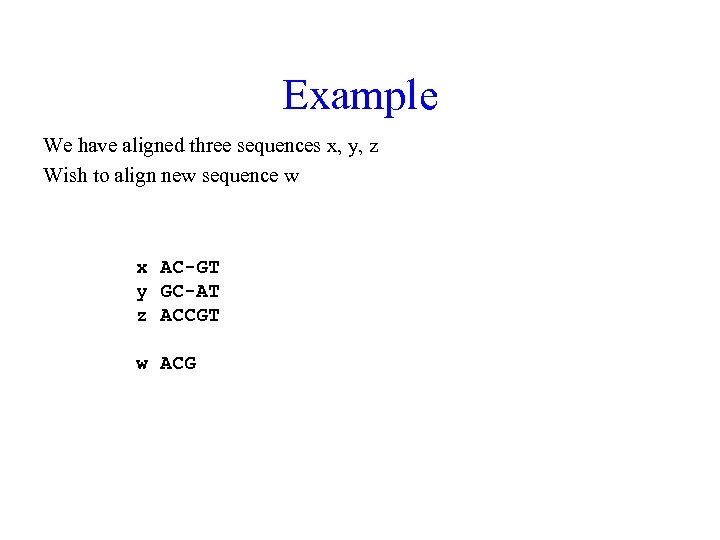

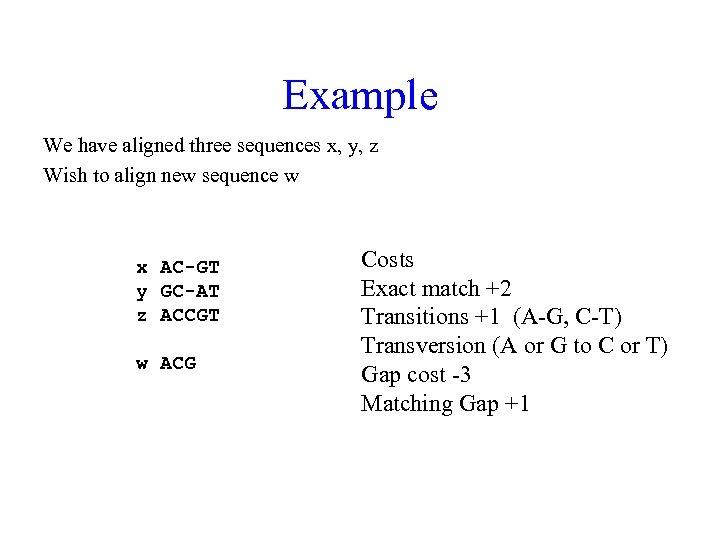

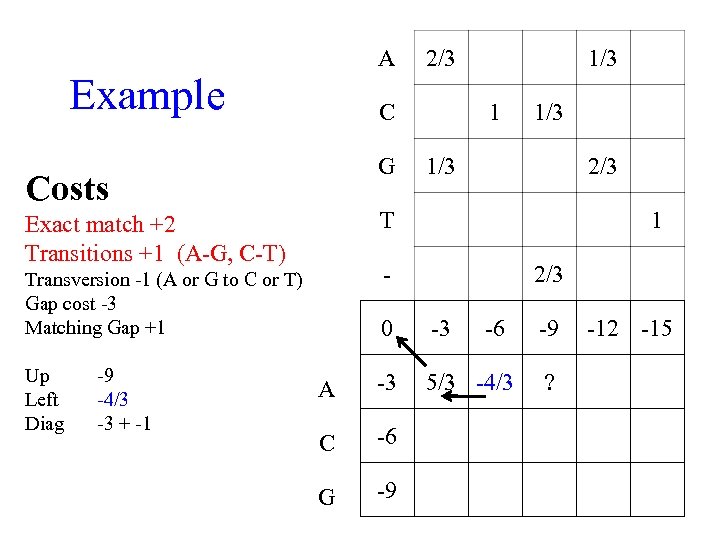

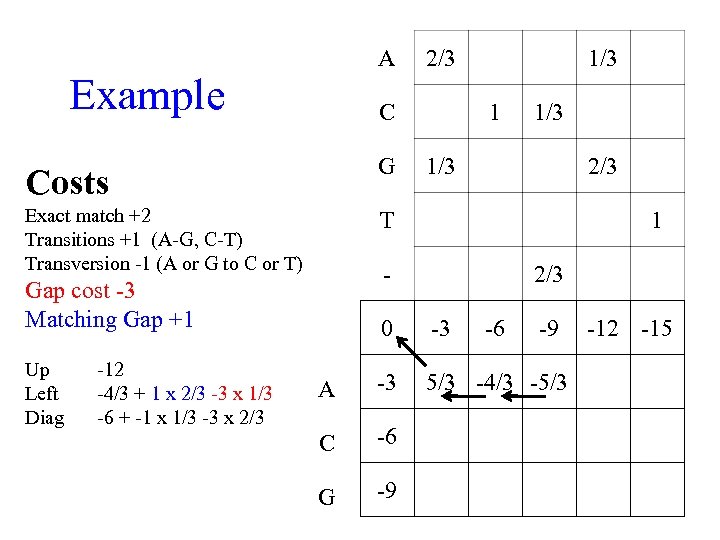

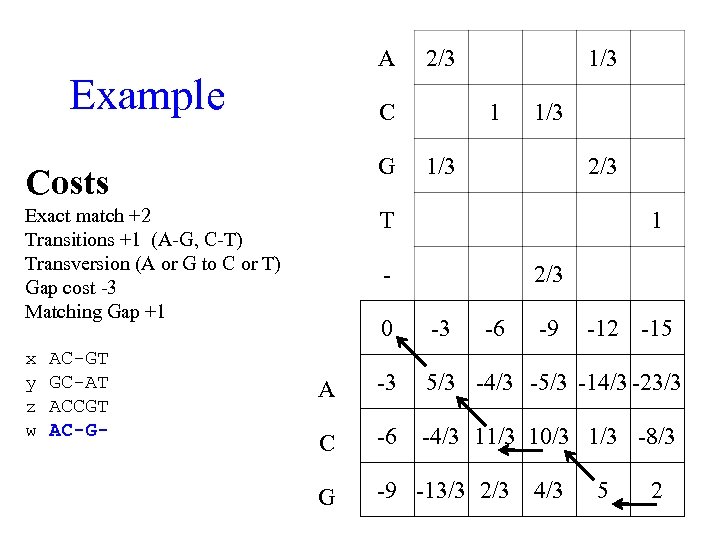

Example We have aligned three sequences x, y, z Wish to align new sequence w x AC-GT y GC-AT z ACCGT w ACG

Example We have aligned three sequences x, y, z Wish to align new sequence w x AC-GT y GC-AT z ACCGT w ACG Costs Exact match +2 Transitions +1 (A-G, C-T) Transversion (A or G to C or T) Gap cost -3 Matching Gap +1

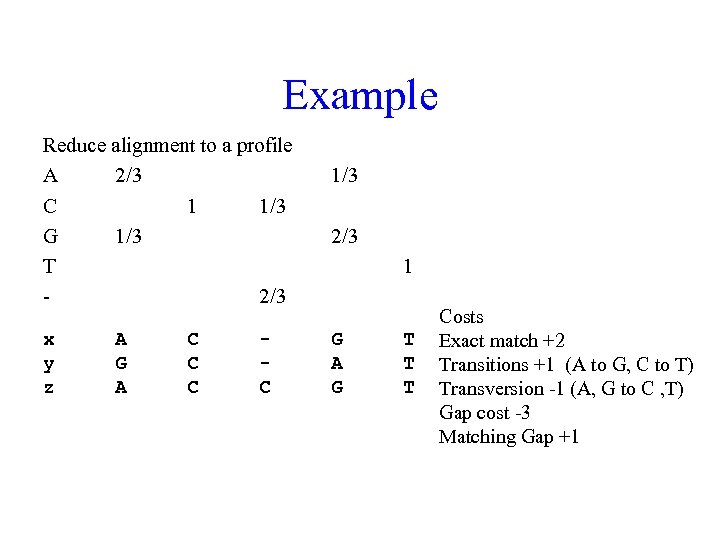

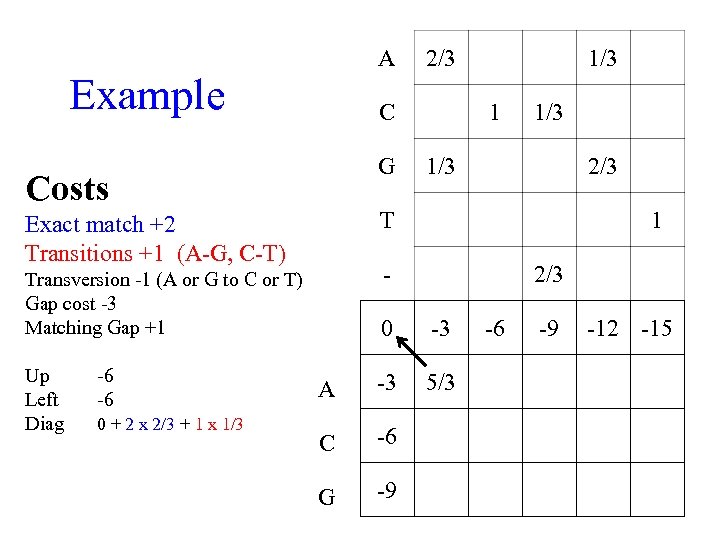

Example Reduce alignment to a profile A 2/3 C 1 1/3 G 1/3 T 2/3 x y z A G A C C 1/3 2/3 1 G A G T T T Costs Exact match +2 Transitions +1 (A to G, C to T) Transversion -1 (A, G to C , T) Gap cost -3 Matching Gap +1

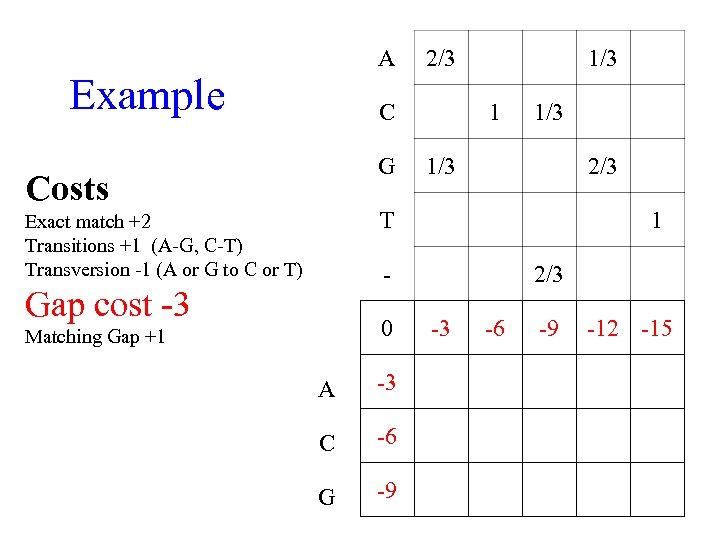

A Example 2/3 C G Costs 1/3 1/3 2/3 T Exact match +2 Transitions +1 (A-G, C-T) Transversion -1 (A or G to C or T) 1 - Gap cost -3 0 Matching Gap +1 A -3 C -6 G -9 2/3 -3 -6 -9 -12 -15

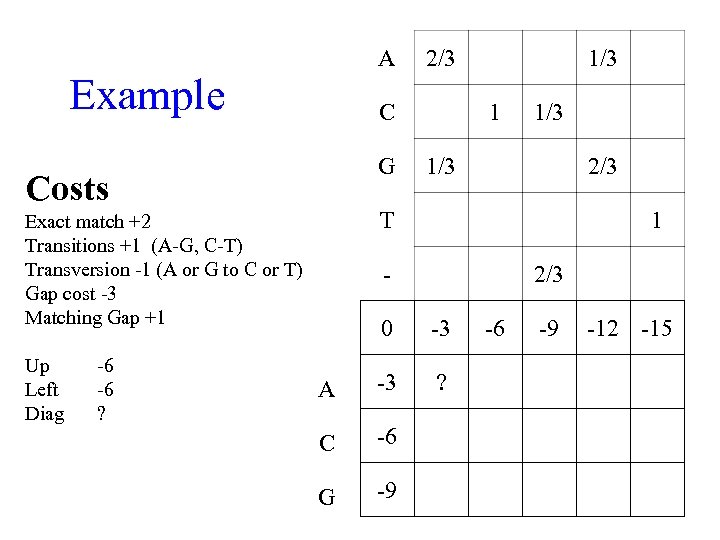

A Example C G Costs -6 -6 ? 1/3 1/3 2/3 T Exact match +2 Transitions +1 (A-G, C-T) Transversion -1 (A or G to C or T) Gap cost -3 Matching Gap +1 Up Left Diag 2/3 1 - 2/3 0 -3 A -3 ? C -6 G -9 -6 -9 -12 -15

A Example C G Costs 0 + 2 x 2/3 + 1 x 1/3 1/3 2/3 1 - Transversion -1 (A or G to C or T) Gap cost -3 Matching Gap +1 -6 -6 1/3 T Exact match +2 Transitions +1 (A-G, C-T) Up Left Diag 2/3 0 -3 A -3 5/3 C -6 G -9 -6 -9 -12 -15

A Example C G Costs 1 1/3 2/3 1 - Transversion -1 (A or G to C or T) Gap cost -3 Matching Gap +1 -9 -4/3 -3 + -1 1/3 T Exact match +2 Transitions +1 (A-G, C-T) Up Left Diag 2/3 0 -3 -6 A -3 5/3 -4/3 C -6 G -9 -9 ? -12 -15

A Example 2/3 C Costs G Exact match +2 Transitions +1 (A-G, C-T) Transversion -1 (A or G to C or T) 1/3 1 1/3 T -12 -4/3 + 1 x 2/3 -3 x 1/3 -6 + -1 x 1/3 -3 x 2/3 1 - Gap cost -3 Matching Gap +1 Up Left Diag 1/3 2/3 0 -3 -6 -9 A -3 5/3 -4/3 -5/3 C -6 G -9 -12 -15

A Example 2/3 C Costs G Exact match +2 Transitions +1 (A-G, C-T) Transversion (A or G to C or T) Gap cost -3 Matching Gap +1 1/3 T x y z w AC-GT GC-AT ACCGT AC-G- 1/3 2/3 1 - 2/3 0 -3 -6 -9 -12 -15 A -3 5/3 -4/3 -5/3 -14/3 -23/3 C -6 -4/3 11/3 10/3 1/3 -8/3 G -9 -13/3 2/3 4/3 5 2

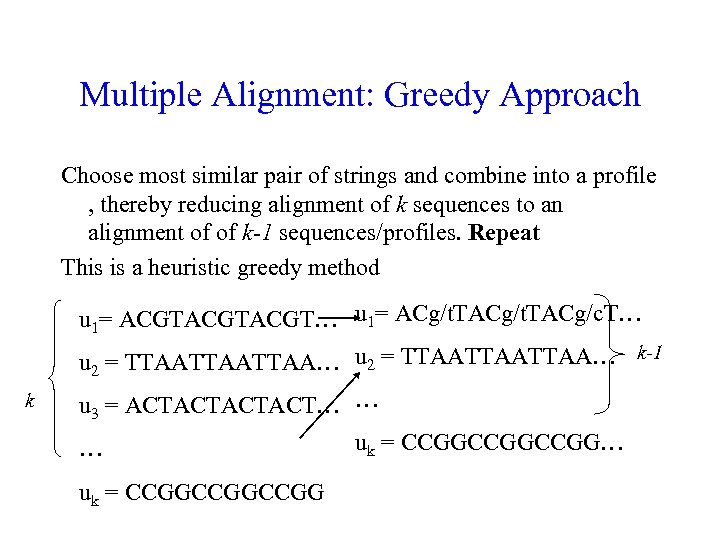

Multiple Alignment: Greedy Approach Choose most similar pair of strings and combine into a profile , thereby reducing alignment of k sequences to an alignment of of k-1 sequences/profiles. Repeat This is a heuristic greedy method u 1= ACGTACGT… u 1= ACg/t. TACg/c. T… u 2 = TTAATTAATTAA… k-1 k u 3 = ACTACT… … … uk = CCGGCCGGCCGG…

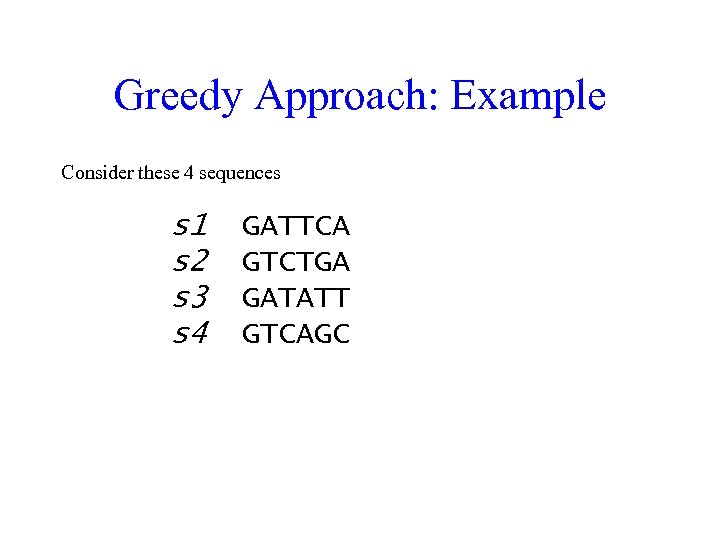

Greedy Approach: Example Consider these 4 sequences s 1 s 2 s 3 s 4 GATTCA GTCTGA GATATT GTCAGC

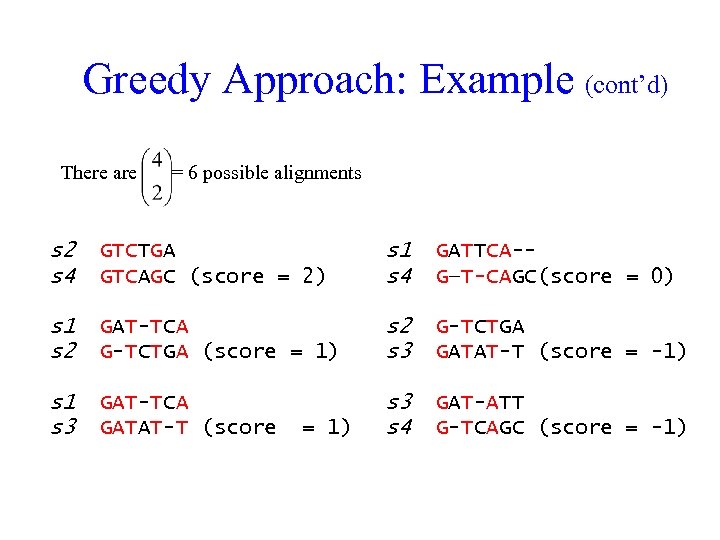

Greedy Approach: Example (cont’d) There are = 6 possible alignments s 2 s 4 GTCTGA GTCAGC (score = 2) s 1 s 4 GATTCA-G—T-CAGC(score = 0) s 1 s 2 GAT-TCA G-TCTGA (score = 1) s 2 s 3 G-TCTGA GATAT-T (score = -1) s 1 s 3 GAT-TCA GATAT-T (score s 3 s 4 GAT-ATT G-TCAGC (score = -1) = 1)

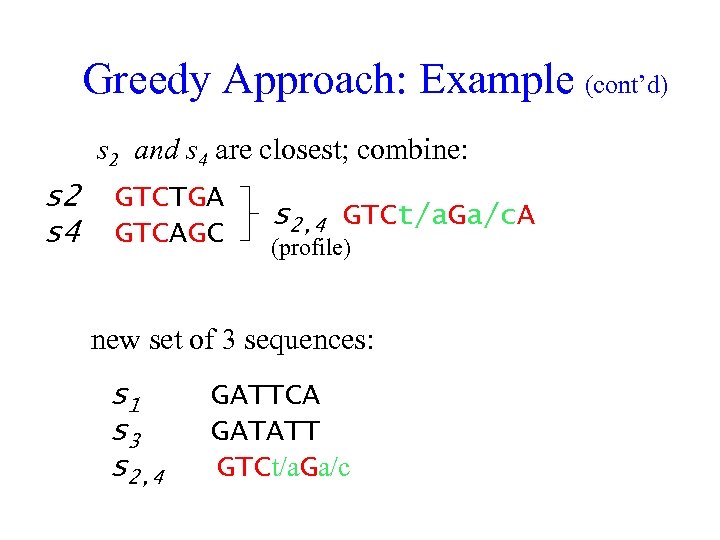

Greedy Approach: Example (cont’d) s 2 and s 4 are closest; combine: s 2 s 4 GTCTGA GTCAGC s 2, 4 GTCt/a. Ga/c. A (profile) new set of 3 sequences: s 1 s 3 s 2, 4 GATTCA GATATT GTCt/a. Ga/c

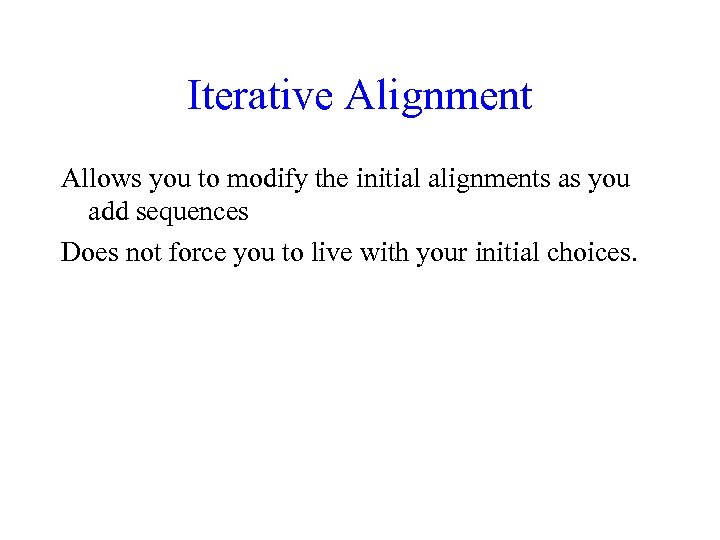

Iterative Alignment Allows you to modify the initial alignments as you add sequences Does not force you to live with your initial choices.

References Apostolico A 1, Giancarlo R. , Sequence alignment in molecular biology, J Comput Biol. 1998 Summer; 5(2): 173 -96. Dayhoff, M. O. ; Schwartz, R. M. ; Orcutt, B. C. (1978). "A model of evolutionary change in proteins". Atlas of Protein Sequence and Structure 5 (3): 345– 352. Henikoff, Steven; Henikoff, Jorja (1992). "Amino acid substitution matrices from protein blocks". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 89 (22): 10915– 9. Altschul, SF (1991). "Amino acid substitution matrices from an information theoretic perspective". Journal of molecular biology 219 (3): 555– 65.

Summary We have been able to use the same Dynamic Programming Framework to address a number of problems Global Alignment (0, -1, -2, -3 on both axes) Pattern Matching (0, -1, -2, -3 on one axis, 0 on the other) Local Alignment (zeros everywhere – axes and interior) We have been able to fold in Affine Gap penalty as well. We have seen ways to modify the matching score to provide more realistic matching scores: PAM and BLOSUM Taken a brief look at a hard problem: multiple alignment We have seen a linear space algorithm for alignment

330e1972ab21be1a983b31aaa2183faf.ppt