1c6545ced21bcc33e3aaac34e3da92e5.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 113

1

Learning Objectives After taking part in this activity, participants should be better able to: – Assess the significant clinical consequences and burden of AF – Apply new practice guidelines/best practices and performance measures for the management of AF – Interpret the latest clinical data on rate-control and rhythm-control strategies for the management of patients with AF – Demonstrate an evidence-based approach for reducing thromboembolic risk in patients with AF 2

Faculty Disclosure The Network for Continuing Medical Education requires that CME faculty disclose, during the planning of an activity, the existence of any personal financial or other relationships they or their spouses/partners have with the commercial supporter of the activity or with the manufacturer of any commercial product or service discussed in the activity. Faculty and planner disclosure information is included in the handout materials.

Epidemiology and Burden of Disease 4

Case: 65 -Year-Old Man With Recent Episodes of Palpitations, Weakness, and Lightheadedness Presentation ● A 65 -year-old man presents with episodes of palpitations, weakness, and significant lightheadedness ● He describes his symptoms, which have been occurring as often as 3 times each day for about 1 week, as severe and debilitating 5

Case: 65 -Year-Old Man With Recent Episodes of Palpitations, Weakness, and Lightheadedness Medical History/Current Medications The patient has been diagnosed with diabetes, hypertension, and sleep apnea syndrome, and is taking the following medications: – Lisinopril 10 mg/d – Metoprolol 50 mg/d – Insulin (0. 6 U/kg nightly) 6

Case: 65 -Year-Old Man With Recent Episodes of Palpitations, Weakness, and Lightheadedness Physical Findings ● BP: 145/90 mm Hg; HR: 85 bpm ● Weight: 180 lb (82 kg); height: 5’ 10”; BMI: 25. 9 m 2/kg ● Chest auscultation and heart sounds – Normal S 1 and S 2, no murmurs – Irregularly irregular rhythm ● Abdominal examination findings: soft and nontender 7

Epidemiology of AF ● Most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia 1 ● Currently affects 5. 1 million Americans 2 ● Prevalence expected to increase to 12. 1 million by 2050 (15. 9 million if increase in incidence continues)2 ● Preferentially affects men and the elderly 1, 2 ● Lifetime risk of developing AF: ~1 in 4 for adults 40 years of age 3 1. Lloyd-Jones D, et al. [published online ahead of print December 17, 2009]. Circulation. doi: 10. 1161/CIRCULATIONAHA. 109. 192667. 2. Miyasaka Y, et al. Circulation. 2006; 114(2): 119 -125. 3. Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Circulation. 2004; 110(9): 1042 -1046. 8

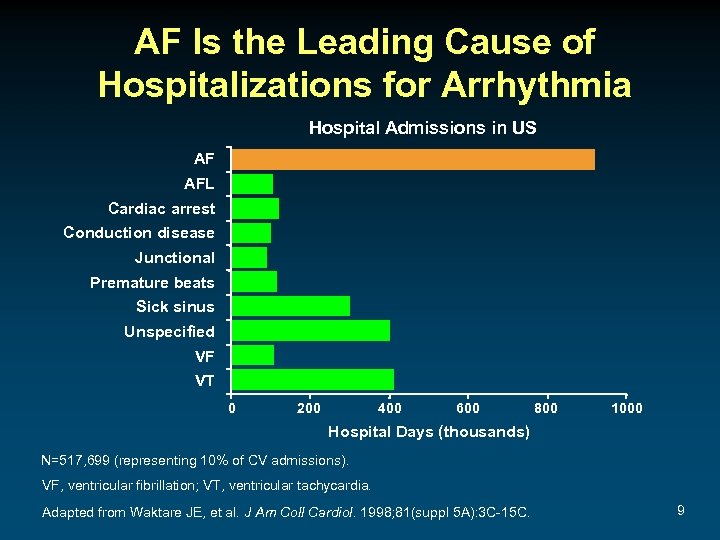

AF Is the Leading Cause of Hospitalizations for Arrhythmia Hospital Admissions in US AF AFL Cardiac arrest Conduction disease Junctional Premature beats Sick sinus Unspecified VF VT 0 200 400 600 800 1000 Hospital Days (thousands) N=517, 699 (representing 10% of CV admissions). VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia. Adapted from Waktare JE, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998; 81(suppl 5 A): 3 C-15 C. 9

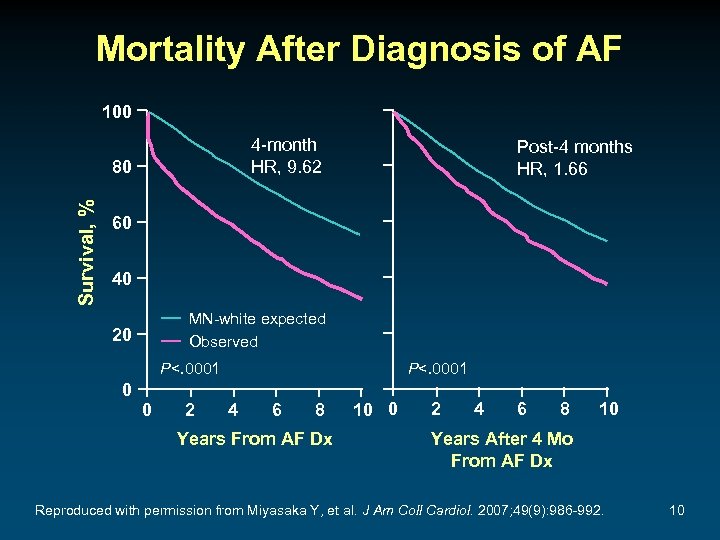

Mortality After Diagnosis of AF 100 4 -month HR, 9. 62 Survival, % 80 Post-4 months HR, 1. 66 60 40 MN-white expected Observed 20 P<. 0001 0 0 2 P<. 0001 4 6 8 Years From AF Dx 10 0 2 4 6 8 10 Years After 4 Mo From AF Dx Reproduced with permission from Miyasaka Y, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007; 49(9): 986 -992. 10

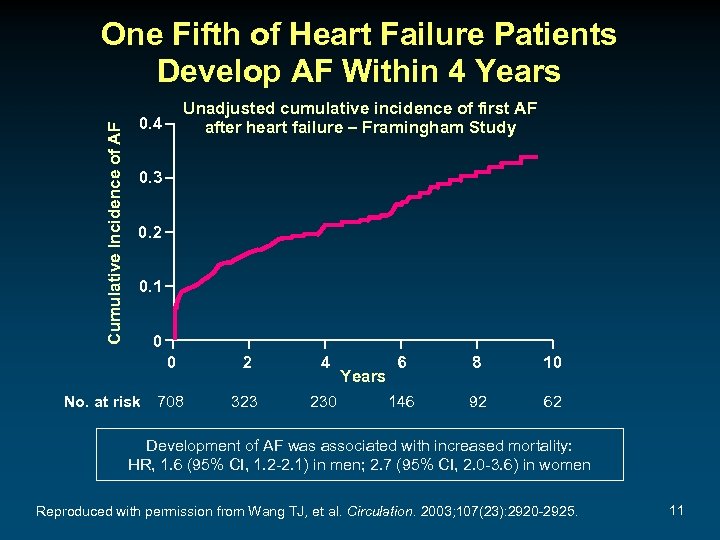

Cumulative Incidence of AF One Fifth of Heart Failure Patients Develop AF Within 4 Years Unadjusted cumulative incidence of first AF after heart failure – Framingham Study 0. 4 0. 3 0. 2 0. 1 0 0 No. at risk 708 2 4 323 230 Years 6 8 10 146 92 62 Development of AF was associated with increased mortality: HR, 1. 6 (95% CI, 1. 2 -2. 1) in men; 2. 7 (95% CI, 2. 0 -3. 6) in women Reproduced with permission from Wang TJ, et al. Circulation. 2003; 107(23): 2920 -2925. 11

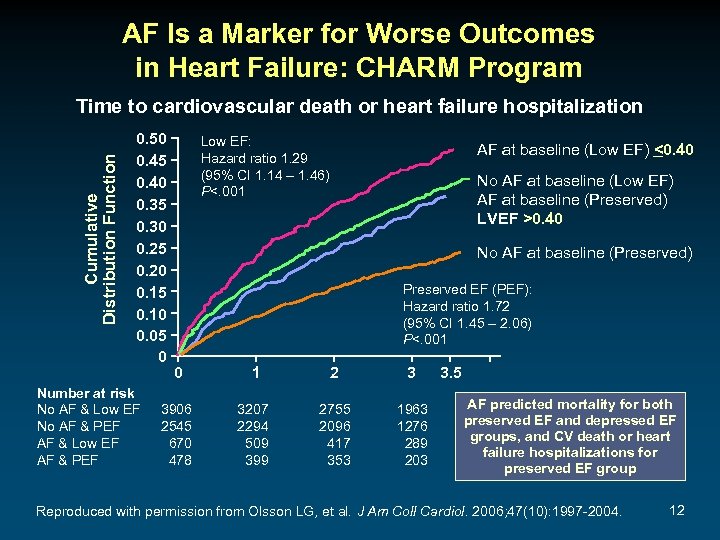

AF Is a Marker for Worse Outcomes in Heart Failure: CHARM Program Cumulative Distribution Function Time to cardiovascular death or heart failure hospitalization 0. 50 0. 45 0. 40 0. 35 0. 30 0. 25 0. 20 0. 15 0. 10 0. 05 0 Number at risk No AF & Low EF No AF & PEF AF & Low EF AF & PEF Low EF: Hazard ratio 1. 29 (95% CI 1. 14 – 1. 46) P<. 001 AF at baseline (Low EF) <0. 40 No AF at baseline (Low EF) AF at baseline (Preserved) LVEF >0. 40 No AF at baseline (Preserved) Preserved EF (PEF): Hazard ratio 1. 72 (95% CI 1. 45 – 2. 06) P<. 001 0 1 2 3 3906 2545 670 478 3207 2294 509 399 2755 2096 417 353 1963 1276 289 203 3. 5 AF predicted mortality for both preserved EF and depressed EF groups, and CV death or heart failure hospitalizations for preserved EF group Reproduced with permission from Olsson LG, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 47(10): 1997 -2004. 12

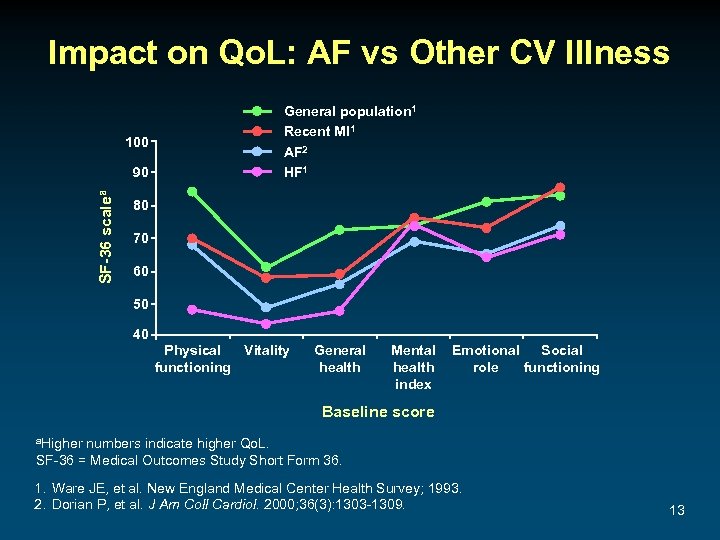

Impact on Qo. L: AF vs Other CV Illness 100 SF-36 scalea 90 General population 1 Recent MI 1 AF 2 HF 1 80 70 60 50 40 Physical Vitality functioning General health Mental health index Emotional Social role functioning Baseline score a. Higher numbers indicate higher Qo. L. SF-36 = Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36. 1. Ware JE, et al. New England Medical Center Health Survey; 1993. 2. Dorian P, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000; 36(3): 1303 -1309. 13

AF Is Associated With Increased Thromboembolic Risk ● Major cause of stroke in elderly 1 ● 5 -fold ↑ in risk of stroke 1, 2 ● 15% of strokes in US are attributable to AF 3 ● Stroke severity (and mortality) is worse with AF than without AF 4 ● Incidence of all-cause stroke in patients with AF: 5%1 ● Stroke risk persists even in asymptomatic AF 5 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Fuster V, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001; 38(4): 1231 -1266. Benjamin EJ, et al. Circulation. 1998; 98(10): 946 -952. Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. Arch Intern Med. 1994; 154(13): 1449 -1457. Dulli DA, et al. Neuroepidemiology. 2003; 22(2): 118 -123. Page RL, et al. Circulation. 2003; 107(8): 1141 -1145. 14

Pathophysiology 15

Pathophysiology of AF • HTN and/or vascular disease ? Inflammation ¯Compliance • Mitral regurgitation Atrial dilatation/stretch • Left ventricular hypertrophy • Diastolic dysfunction ? Inflammation S tretch-activated channels D ispersion of refractoriness P ulmonary vein focal/discharges? Increased vulnerability to AF? Adapted with permission from Gersh BJ, et al. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2005; 7(suppl C): C 5 -C 11. 16

What Happens When AF Persists? Structural Remodeling · LA and LAA dilatation · Fibrosis Electrophysiologic Remodeling · Decrease in Ca++ currents · Shortening of atrial action potential · Increased importance of early activating K+ channels: IKur, IKto Remodeling explains why “AF begets AF” 17

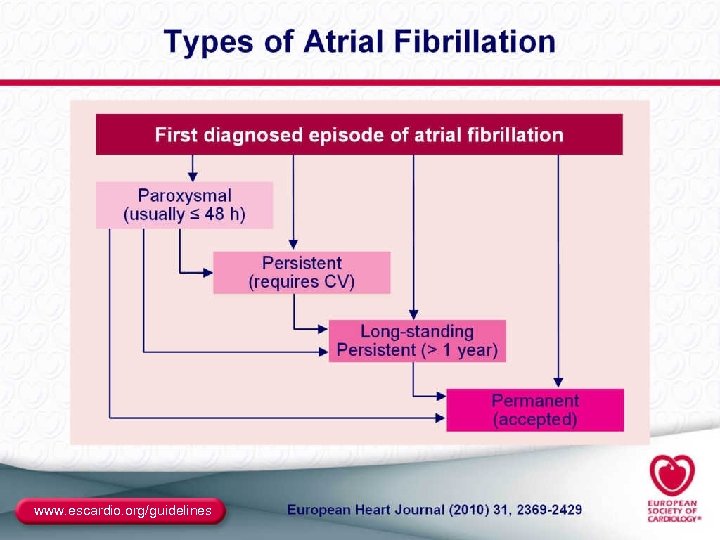

Classification of AF Recurrent AFa (≥ 2 episodes) Paroxysmal • Arrhythmia terminates spontaneously • AF is sustained ≤ 7 days Persistent Permanent • Arrhythmia does not terminate spontaneously • AF is sustained >7 days • Both paroxysmal and persistent AF can become permanent a. Termination with pharmacologic therapy or direct-current cardioversion does not change the designation. Fuster V, et al. Circulation. 2006; 114(7): e 257 -e 354. 18

Clinical Evaluation 19

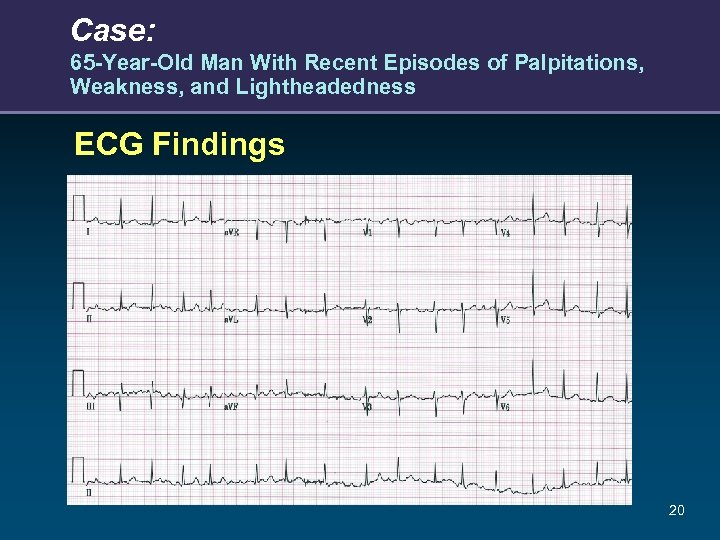

Case: 65 -Year-Old Man With Recent Episodes of Palpitations, Weakness, and Lightheadedness ECG Findings 20

Case: 65 -Year-Old Man With Recent Episodes of Palpitations, Weakness, and Lightheadedness Echocardiogram Findings ● Mild LVH and nl LV function – LV wall thickness 1. 3 cm – LA size 4. 2 21

Case: 65 -Year-Old Man With Recent Episodes of Palpitations, Weakness, and Lightheadedness What other tests would you perform for this patient at this time? A. B. C. D. E. F. 6 -Minute walk or exercise test Holter monitoring/event recording Electrophysiology study Cardiac catheterization Cardiac MRI None 22

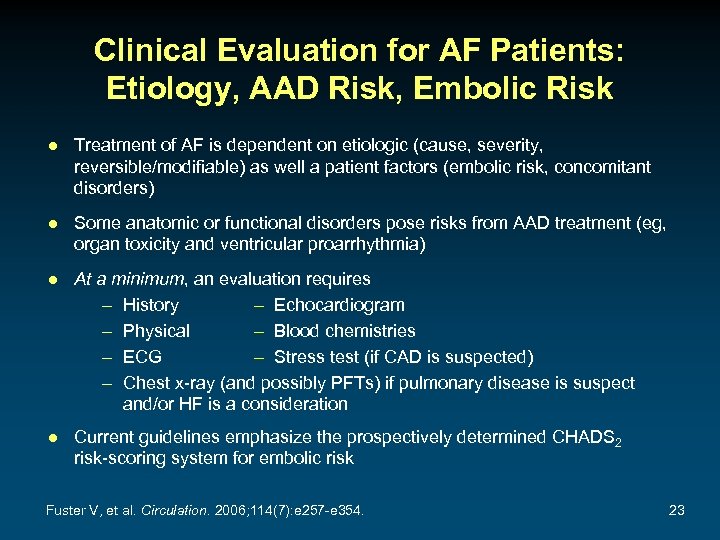

Clinical Evaluation for AF Patients: Etiology, AAD Risk, Embolic Risk ● Treatment of AF is dependent on etiologic (cause, severity, reversible/modifiable) as well a patient factors (embolic risk, concomitant disorders) ● Some anatomic or functional disorders pose risks from AAD treatment (eg, organ toxicity and ventricular proarrhythmia) ● At a minimum, an evaluation requires – History – Echocardiogram – Physical – Blood chemistries – ECG – Stress test (if CAD is suspected) – Chest x-ray (and possibly PFTs) if pulmonary disease is suspect and/or HF is a consideration ● Current guidelines emphasize the prospectively determined CHADS 2 risk-scoring system for embolic risk Fuster V, et al. Circulation. 2006; 114(7): e 257 -e 354. 23

Conditions Frequently Associated With Nonvalvular AF 1 -4 ● ● ● ● ● 1. 2. 3. 4. Hypertension Aging Male sex Obesity/metabolic syndrome/diabetes Ischemic heart disease Heart failure/diastolic dysfunction Obstructive sleep apnea Physical inactivity Thyroid disease Inflammation? Wattigney WA, et al. Circulation. 2003; 108(6): 711 -716. Gersh BJ, et al. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2005; 7(suppl C): C 5 -C 11. Fuster V, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 48(4): 854 -906. Mozaffarian D, et al. Circulation. 2008; 118(8): 800 -807. 24

Case: 65 -Year-Old Man With Recent Episodes of Palpitations, Weakness, and Lightheadedness What is the patient’s diagnosis? A. B. C. D. Paroxysmal AF Persistent AF Permanent AF Other 25

Case: 65 -Year-Old Man With Recent Episodes of Palpitations, Weakness, and Lightheadedness Would you recommend antithrombotic therapy for this patient at this time? A. Yes B. No 26

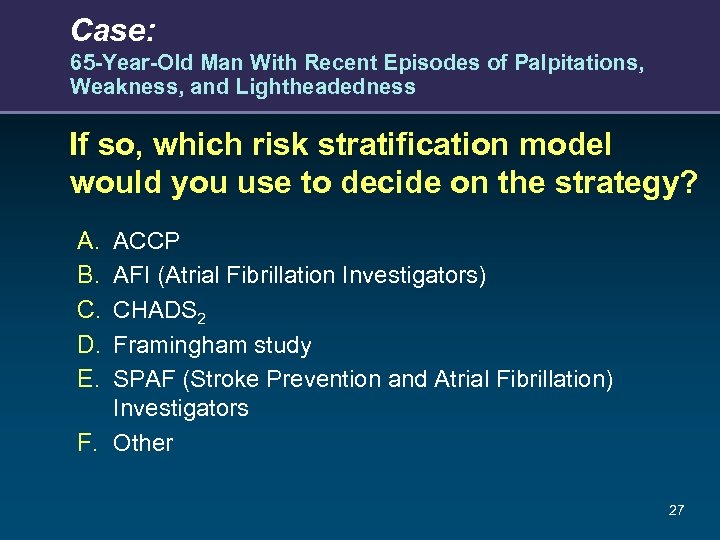

Case: 65 -Year-Old Man With Recent Episodes of Palpitations, Weakness, and Lightheadedness If so, which risk stratification model would you use to decide on the strategy? A. B. C. D. E. ACCP AFI (Atrial Fibrillation Investigators) CHADS 2 Framingham study SPAF (Stroke Prevention and Atrial Fibrillation) Investigators F. Other 27

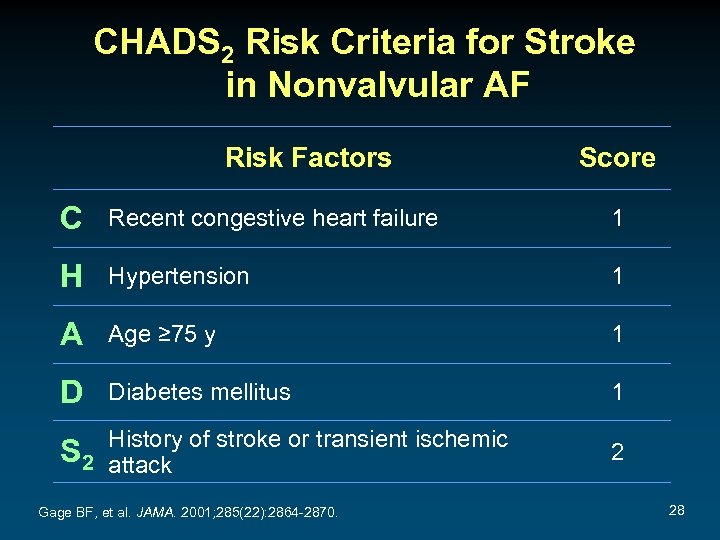

CHADS 2 Risk Criteria for Stroke in Nonvalvular AF Risk Factors Score C Recent congestive heart failure 1 H Hypertension 1 A Age ≥ 75 y 1 D Diabetes mellitus 1 History of stroke or transient ischemic S 2 attack Gage BF, et al. JAMA. 2001; 285(22): 2864 -2870. 2 28

Stroke Risk in Patients With Nonvalvular AF Not Treated With Anticoagulation Based on the CHADS 2 Index Patients (N=1733) 120 (95% CI) CHADS 2 Score 0 463 1 523 2 337 3 220 4 65 5 5 6 0 5 10 15 20 25 Adjusted Stroke Rate (% per y) Warfarin 30 CHADS 2, Congestive heart failure, Hypertension, Age >75, Diabetes mellitus, and prior Stroke or transient ischemic attack. Gage BF, et al. JAMA. 2001; 285(22): 2864 -2870. 29

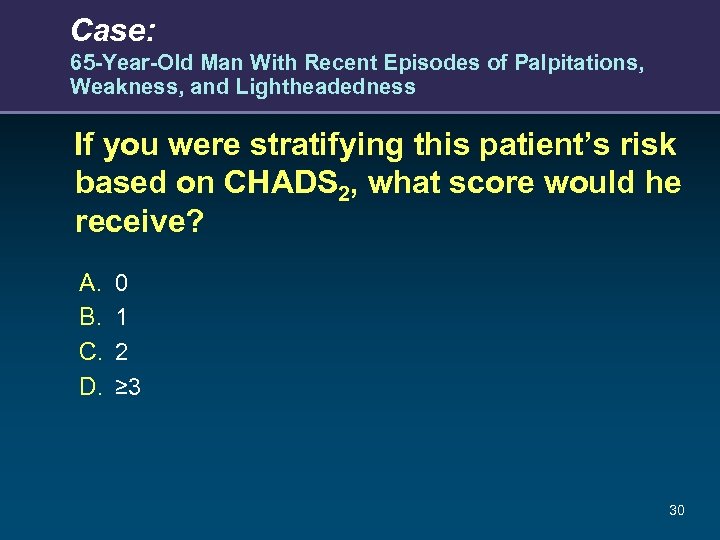

Case: 65 -Year-Old Man With Recent Episodes of Palpitations, Weakness, and Lightheadedness If you were stratifying this patient’s risk based on CHADS 2, what score would he receive? A. B. C. D. 0 1 2 ≥ 3 30

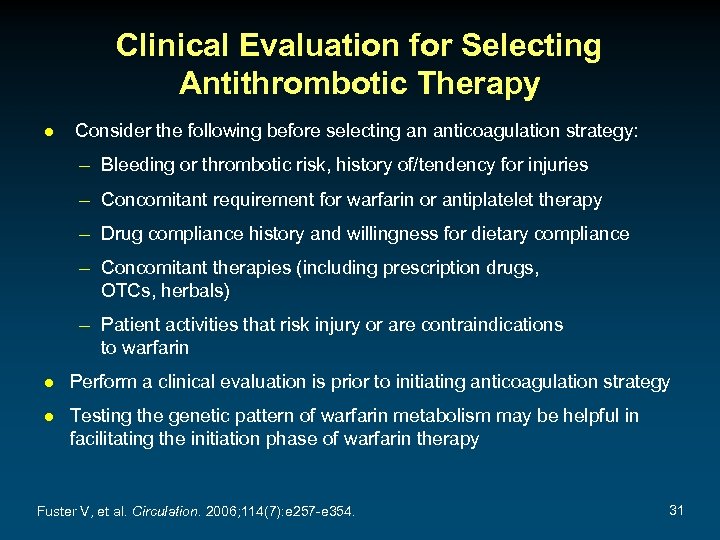

Clinical Evaluation for Selecting Antithrombotic Therapy ● Consider the following before selecting an anticoagulation strategy: – Bleeding or thrombotic risk, history of/tendency for injuries – Concomitant requirement for warfarin or antiplatelet therapy – Drug compliance history and willingness for dietary compliance – Concomitant therapies (including prescription drugs, OTCs, herbals) – Patient activities that risk injury or are contraindications to warfarin ● Perform a clinical evaluation is prior to initiating anticoagulation strategy ● Testing the genetic pattern of warfarin metabolism may be helpful in facilitating the initiation phase of warfarin therapy Fuster V, et al. Circulation. 2006; 114(7): e 257 -e 354. 31

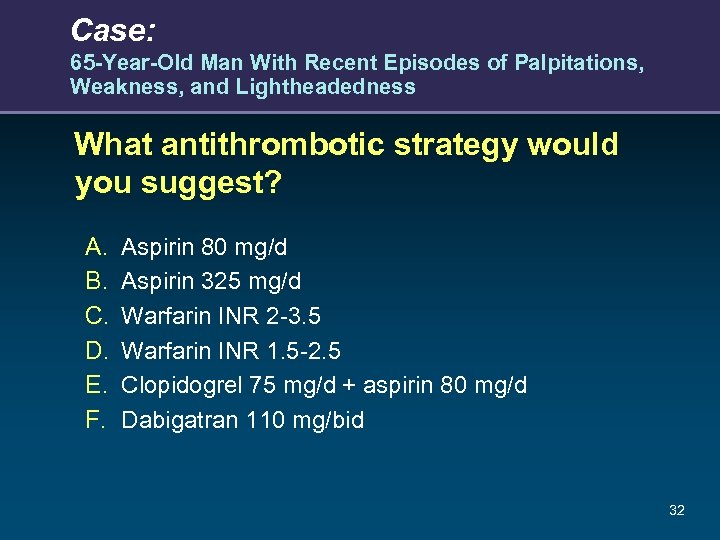

Case: 65 -Year-Old Man With Recent Episodes of Palpitations, Weakness, and Lightheadedness What antithrombotic strategy would you suggest? A. B. C. D. E. F. Aspirin 80 mg/d Aspirin 325 mg/d Warfarin INR 2 -3. 5 Warfarin INR 1. 5 -2. 5 Clopidogrel 75 mg/d + aspirin 80 mg/d Dabigatran 110 mg/bid 32

Treatment 33

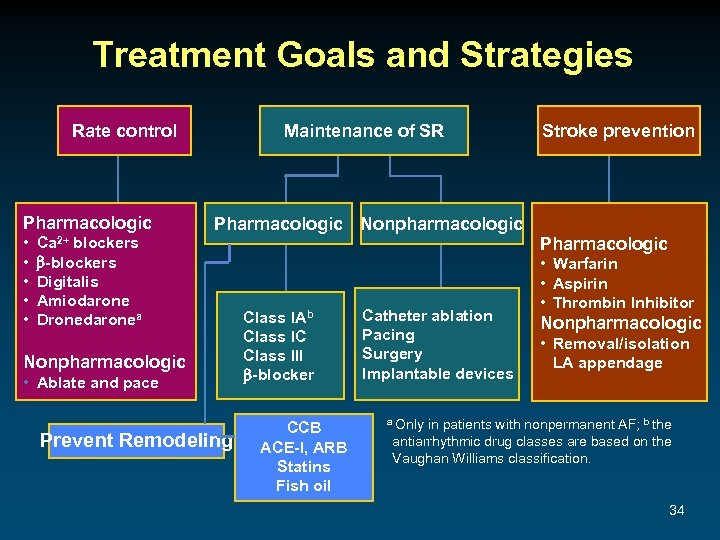

Treatment Goals and Strategies Rate control Pharmacologic • • • Ca 2+ blockers -blockers Digitalis Amiodarone Dronedaronea Maintenance of SR Pharmacologic Nonpharmacologic • Ablate and pace Prevent Remodeling Class IAb Class IC Class III -blocker CCB ACE-I, ARB Statins Fish oil Catheter ablation Pacing Surgery Implantable devices Stroke prevention Pharmacologic • Warfarin • Aspirin • Thrombin Inhibitor Nonpharmacologic • Removal/isolation LA appendage a Only in patients with nonpermanent AF; b the antiarrhythmic drug classes are based on the Vaughan Williams classification. 34

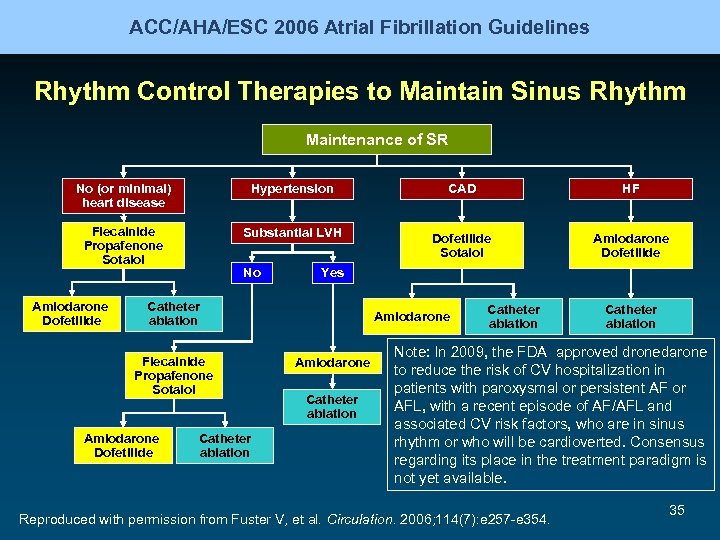

ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Atrial Fibrillation Guidelines Rhythm Control Therapies to Maintain Sinus Rhythm Maintenance of SR No (or minimal) heart disease Hypertension CAD HF Flecainide Propafenone Sotalol Substantial LVH Dofetilide Sotalol Amiodarone Dofetilide No Yes Catheter ablation Flecainide Propafenone Sotalol Amiodarone Dofetilide Catheter ablation Amiodarone Catheter ablation Note: In 2009, the FDA approved dronedarone to reduce the risk of CV hospitalization in patients with paroxysmal or persistent AF or AFL, with a recent episode of AF/AFL and associated CV risk factors, who are in sinus rhythm or who will be cardioverted. Consensus regarding its place in the treatment paradigm is not yet available. Reproduced with permission from Fuster V, et al. Circulation. 2006; 114(7): e 257 -e 354. 35

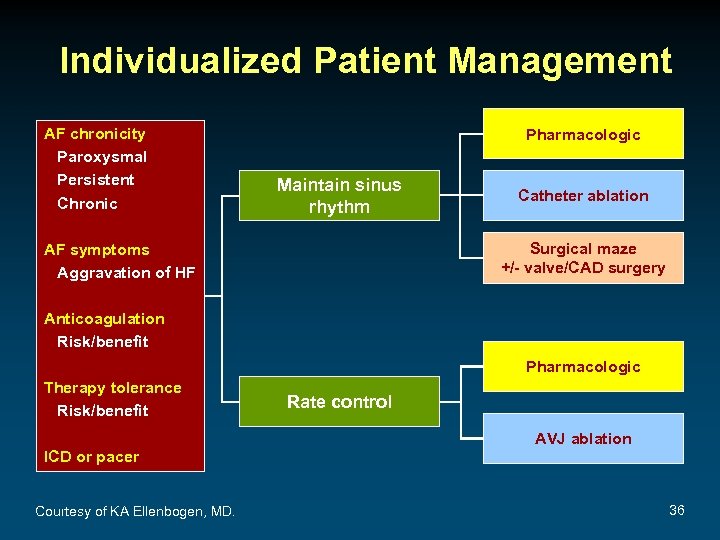

Individualized Patient Management AF chronicity Paroxysmal Persistent Chronic Pharmacologic Maintain sinus rhythm Catheter ablation Surgical maze +/- valve/CAD surgery AF symptoms Aggravation of HF Anticoagulation Risk/benefit Pharmacologic Therapy tolerance Risk/benefit ICD or pacer Courtesy of KA Ellenbogen, MD. Rate control AVJ ablation 36

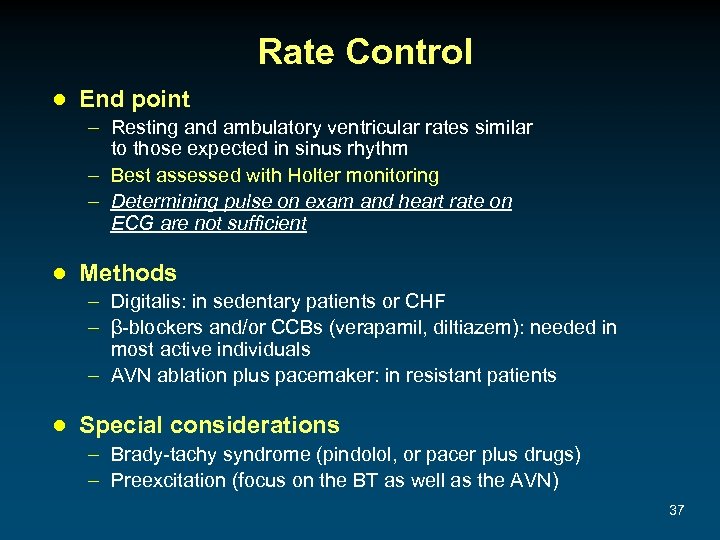

Rate Control ● End point – Resting and ambulatory ventricular rates similar to those expected in sinus rhythm – Best assessed with Holter monitoring – Determining pulse on exam and heart rate on ECG are not sufficient ● Methods – Digitalis: in sedentary patients or CHF – β-blockers and/or CCBs (verapamil, diltiazem): needed in most active individuals – AVN ablation plus pacemaker: in resistant patients ● Special considerations – Brady-tachy syndrome (pindolol, or pacer plus drugs) – Preexcitation (focus on the BT as well as the AVN) 37

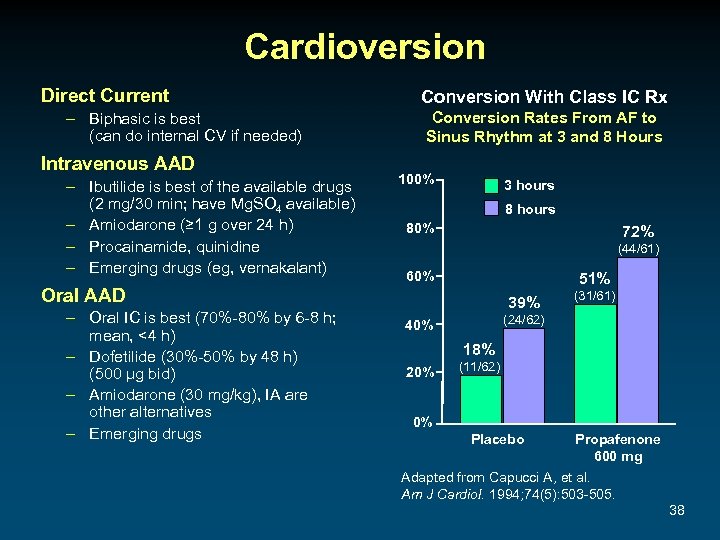

Cardioversion Direct Current – Biphasic is best (can do internal CV if needed) Intravenous AAD – Ibutilide is best of the available drugs (2 mg/30 min; have Mg. SO 4 available) – Amiodarone (≥ 1 g over 24 h) – Procainamide, quinidine – Emerging drugs (eg, vernakalant) Conversion With Class IC Rx Conversion Rates From AF to Sinus Rhythm at 3 and 8 Hours 100% 3 hours 80% 72% (44/61) 60% 51% Oral AAD – Oral IC is best (70%-80% by 6 -8 h; mean, <4 h) – Dofetilide (30%-50% by 48 h) (500 μg bid) – Amiodarone (30 mg/kg), IA are other alternatives – Emerging drugs 39% (31/61) (24/62) 40% 18% 20% (11/62) 0% Placebo Propafenone 600 mg Adapted from Capucci A, et al. Am J Cardiol. 1994; 74(5): 503 -505. 38

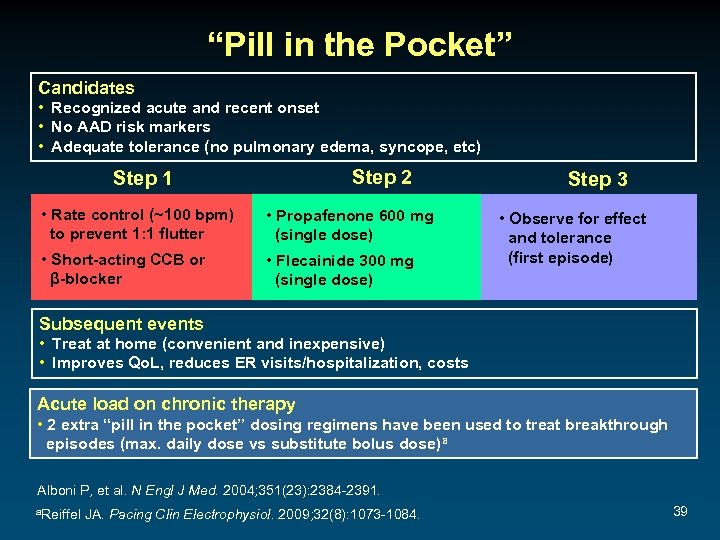

“Pill in the Pocket” Candidates • Recognized acute and recent onset • No AAD risk markers • Adequate tolerance (no pulmonary edema, syncope, etc) Step 2 Step 1 • Rate control (~100 bpm) to prevent 1: 1 flutter • Propafenone 600 mg (single dose) • Short-acting CCB or β-blocker • Flecainide 300 mg (single dose) Step 3 • Observe for effect and tolerance (first episode) Subsequent events • Treat at home (convenient and inexpensive) • Improves Qo. L, reduces ER visits/hospitalization, costs Acute load on chronic therapy • 2 extra “pill in the pocket” dosing regimens have been used to treat breakthrough episodes (max. daily dose vs substitute bolus dose)a Alboni P, et al. N Engl J Med. 2004; 351(23): 2384 -2391. a. Reiffel JA. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2009; 32(8): 1073 -1084. 39

Case: 65 -Year-Old Man With Recent Episodes of Palpitations, Weakness, and Lightheadedness Which of the following management goals may not be necessary in every patient with AF? A. Control of the ventricular rate B. Reduction of thromboembolism risk (particularly stroke) C. Restoration and maintenance of sinus rhythm 40

AAD Treatment Goals ● Remember to keep goals realistic! ● AF is rarely life-threatening and is usually recurrent ● Thus, goals should be to: – Reduce the frequency of recurrences – Reduce the duration of recurrences – Reduce the severity of recurrences – Minimize intolerance and risk of therapy 41

Antiarrhythmic Drugs for AF ● Class I: – Class IC: propafenone (also very weak β-blocker), flecainide (no β-blockade effects) • Sustained-release propafenone (Rythmol SR) and flecainide are bid; • Propafenone appears to be less proarrhythmic – Class IA: disopyramide, quinidine, procainamide • No longer included in the ACC/AHA/ESC algorithm • Disopyramide may be useful in vagally induced AF ● Class III: – – Sotalol (class III plus β-blocker) Dofetilide (pure class III) Amiodarone (class III plus class I, IV) Dronedarone (similar to amiodarone with different pharmacokinetics and markedly reduced organ toxic potential) 42

Ventricular Proarrhythmia With AAD ● Torsade de pointes: – A consequence of class III and IA AAD – Incidence varies within drug class, and with LVH – Can be as low as 0. 1%-0. 4% ● Monomorphic VT: – A consequence of class I AAD (esp. IC) in SHD (ischemic, impaired cell connections) – Thus, class I AAD are contraindicated as first-line therapy in SHD patients ● Ventricular fibrillation: – May degenerate from Td. P or VT – May be idiopathic 43

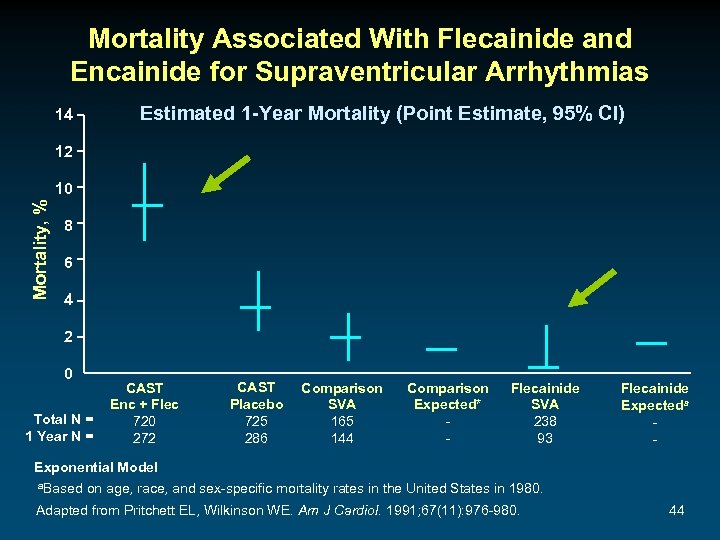

Mortality Associated With Flecainide and Encainide for Supraventricular Arrhythmias Estimated 1 -Year Mortality (Point Estimate, 95% CI) 14 12 Mortality, % 10 8 6 4 2 0 Total N = 1 Year N = CAST Enc + Flec 720 272 CAST Placebo 725 286 Comparison SVA 165 144 Comparison Expected* - Flecainide SVA 238 93 Flecainide Expecteda - Exponential Model a. Based on age, race, and sex-specific mortality rates in the United States in 1980. Adapted from Pritchett EL, Wilkinson WE. Am J Cardiol. 1991; 67(11): 976 -980. 44

Case: 65 -Year-Old Man With Recent Episodes of Palpitations, Weakness, and Lightheadedness What treatment to manage the AF would you suggest at this time? A. B. C. D. E. Catheter ablation Flecainide Dronedarone Amiodarone AV node ablation and PPM 45

Case: 65 -Year-Old Man With Recent Episodes of Palpitations, Weakness, and Lightheadedness If dronedarone is chosen, where should treatment be initiated? A. Inpatient administration is mandatory B. Outpatient administration is feasible 46

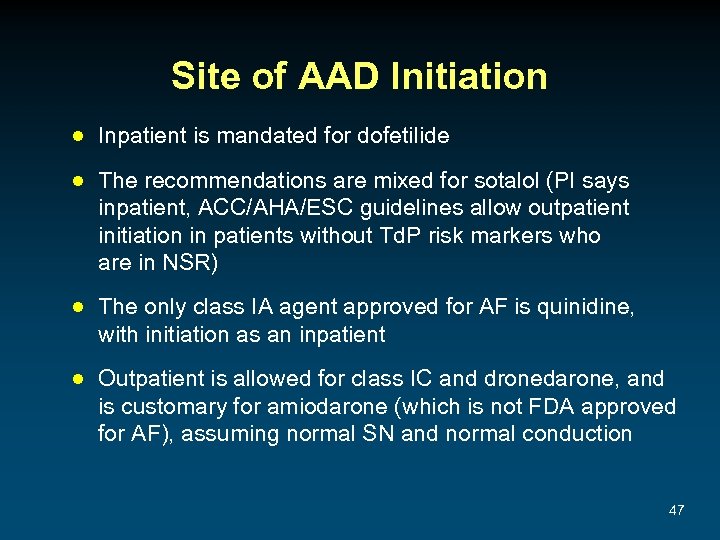

Site of AAD Initiation ● Inpatient is mandated for dofetilide ● The recommendations are mixed for sotalol (PI says inpatient, ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines allow outpatient initiation in patients without Td. P risk markers who are in NSR) ● The only class IA agent approved for AF is quinidine, with initiation as an inpatient ● Outpatient is allowed for class IC and dronedarone, and is customary for amiodarone (which is not FDA approved for AF), assuming normal SN and normal conduction 47

Judging Antiarrhythmic Efficacy ● In patients with symptomatic AF: – Reduction or abolishment of symptoms ● In symptomatic and asymptomatic AF patients: – Normalization of pulse on self-examination twice a day – Assessment with autotriggered loop recorder (devices that can be patient triggered and can automatically record for programmed criteria, including AF) – Assessment with pacemaker interrogation 48

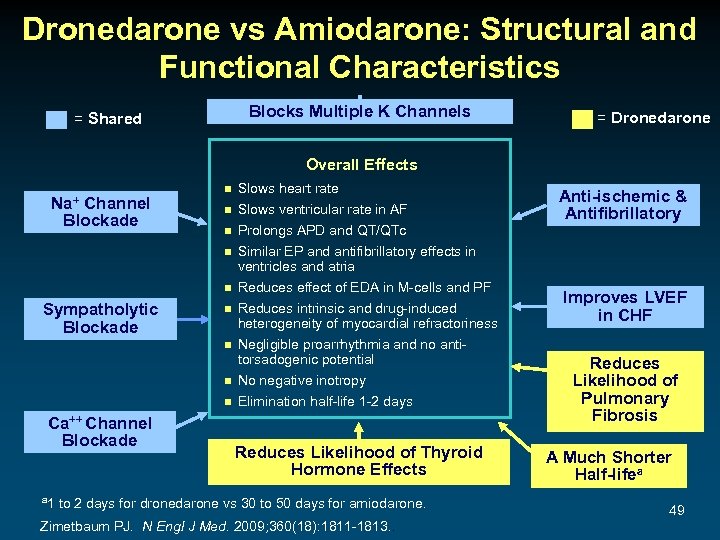

Dronedarone vs Amiodarone: Structural and Functional Characteristics Blocks Multiple K Channels = Shared = Dronedarone Overall Effects Na+ Channel Blockade n n n Sympatholytic Blockade n n Ca++ Channel Blockade a 1 Slows heart rate Slows ventricular rate in AF Prolongs APD and QT/QTc Similar EP and antifibrillatory effects in ventricles and atria Reduces effect of EDA in M-cells and PF Reduces intrinsic and drug-induced heterogeneity of myocardial refractoriness Negligible proarrhythmia and no antitorsadogenic potential No negative inotropy Elimination half-life 1 -2 days Reduces Likelihood of Thyroid Hormone Effects to 2 days for dronedarone vs 30 to 50 days for amiodarone. Zimetbaum PJ. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360(18): 1811 -1813. . Anti-ischemic & Antifibrillatory Improves LVEF in CHF Reduces Likelihood of Pulmonary Fibrosis A Much Shorter Half-lifea 49

The ERATO Rate-Reduction Trial ERATO: Secondary Study End Point Dronedarone Significantly Decreased Ventricular Rate (24 -hour Holter) Dronedarone Significantly Decreased Maximal Exercise Ventricular Rate (Mean ± SEM) Placebo Dronedarone 400 mg bid Ventricular Rate, bpm 95 90 85 90. 2 90. 6 86. 5 11. 7 bpma (P<. 0001) 80 75 70 76. 2 Baseline D 14 Ventricular Rate (bpm) During Maximal Exercise ERATO: Primary Study End Point Placebo Dronedarone 400 mg bid 170 165 160 155 150 145 152. 6 effect estimate by ANCOVA 24. 5 bpma (P<. 0001) 140 135 130 125 120 129. 7 Baseline Time a. Treatment 159. 6 162. 4 D 14 Time a. Treatment effect estimate by ANCOVA Adapted with permission from Davy JM, et al. Am Heart J. 2008; 156(3): 527: e 1 -527. e 9. 50

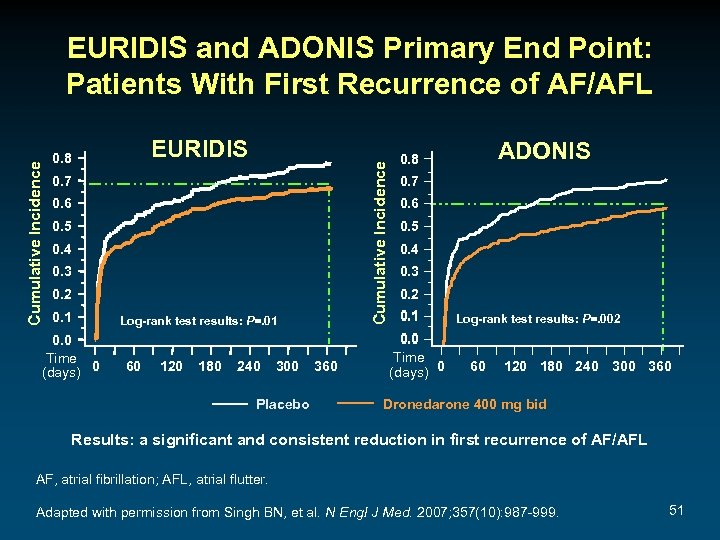

EURIDIS 0. 8 Cumulative Incidence EURIDIS and ADONIS Primary End Point: Patients With First Recurrence of AF/AFL 0. 7 0. 6 0. 5 0. 4 0. 3 0. 2 0. 1 0. 0 Time (days) 0 Log-rank test results: P=. 01 60 120 180 240 300 Placebo 360 ADONIS 0. 8 0. 7 0. 6 0. 5 0. 4 0. 3 0. 2 0. 1 0. 0 Time (days) 0 Log-rank test results: P=. 002 60 120 180 240 300 360 Dronedarone 400 mg bid Results: a significant and consistent reduction in first recurrence of AF/AFL AF, atrial fibrillation; AFL, atrial flutter. Adapted with permission from Singh BN, et al. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357(10): 987 -999. 51

EURIDIS and ADONIS: Dronedarone Reduced Ventricular Rate at First AF/AFL Recurrence Mean Ventricular Rate (with TTM) Placebo 120 116. 6 P<. 001 Dronedarone 117. 5 P<. 001 115 110 104. 6 105 102. 3 100 95 n=102 n=188 n=117 n=199 90 ADONIS EURIDIS TTM, transtelephonic monitoring. Singh BN, et al. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357(10): 987 -999. 52

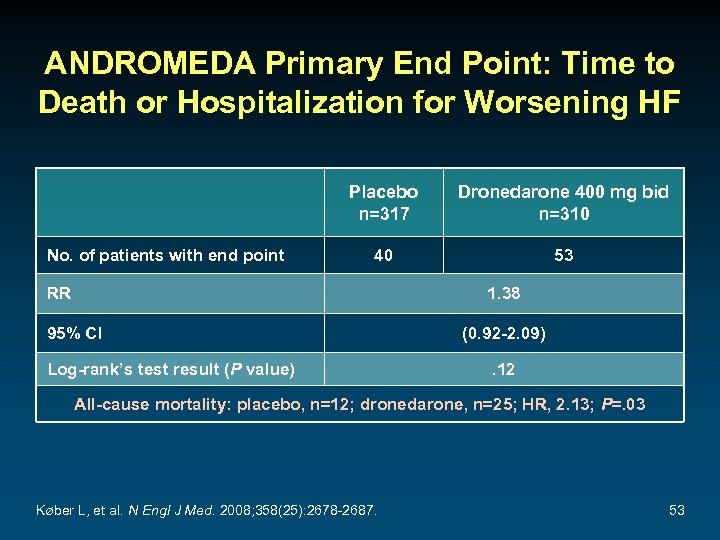

ANDROMEDA Primary End Point: Time to Death or Hospitalization for Worsening HF Placebo n=317 No. of patients with end point Dronedarone 400 mg bid n=310 40 53 RR 1. 38 95% CI Log-rank’s test result (P value) (0. 92 -2. 09). 12 All-cause mortality: placebo, n=12; dronedarone, n=25; HR, 2. 13; P=. 03 Køber L, et al. N Engl J Med. 2008; 358(25): 2678 -2687. 53

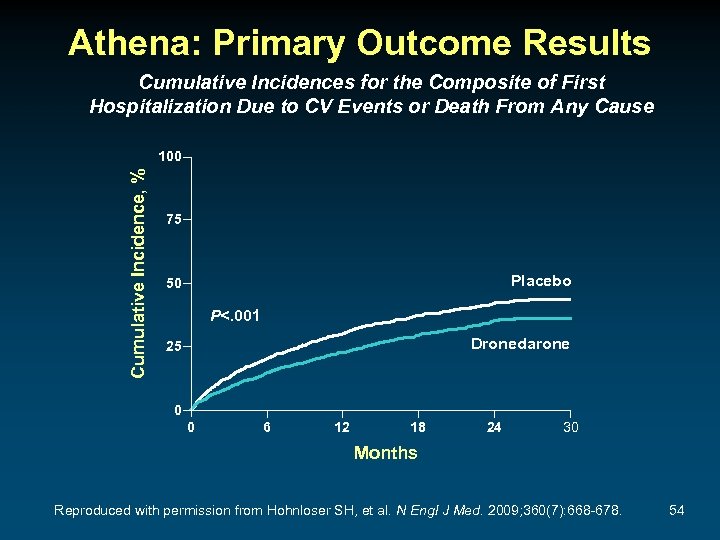

Athena: Primary Outcome Results Cumulative Incidences for the Composite of First Hospitalization Due to CV Events or Death From Any Cause Cumulative Incidence, % 100 75 Placebo 50 P<. 001 Dronedarone 25 0 0 6 12 18 24 30 Months Reproduced with permission from Hohnloser SH, et al. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360(7): 668 -678. 54

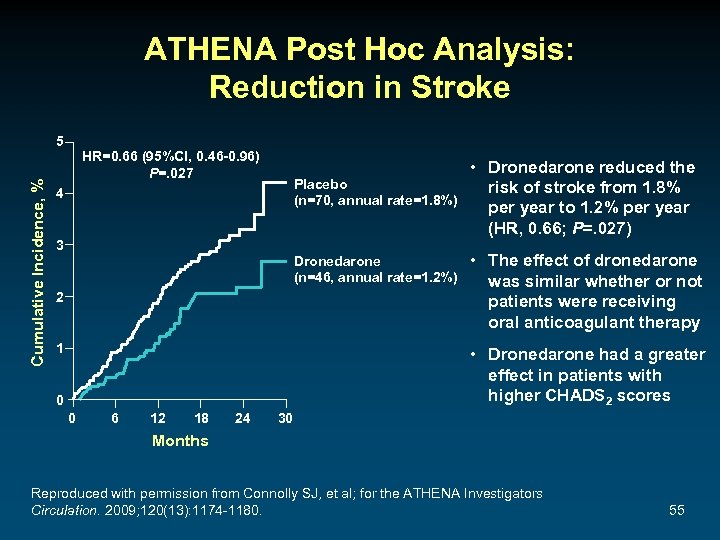

ATHENA Post Hoc Analysis: Reduction in Stroke Cumulative Incidence, % 5 HR=0. 66 (95%Cl, 0. 46 -0. 96) P=. 027 Placebo (n=70, annual rate=1. 8%) 4 3 Dronedarone (n=46, annual rate=1. 2%) 2 1 • Dronedarone reduced the risk of stroke from 1. 8% per year to 1. 2% per year (HR, 0. 66; P=. 027) • The effect of dronedarone was similar whether or not patients were receiving oral anticoagulant therapy • Dronedarone had a greater effect in patients with higher CHADS 2 scores 0 0 6 12 18 24 30 Months Reproduced with permission from Connolly SJ, et al; for the ATHENA Investigators Circulation. 2009; 120(13): 1174 -1180. 55

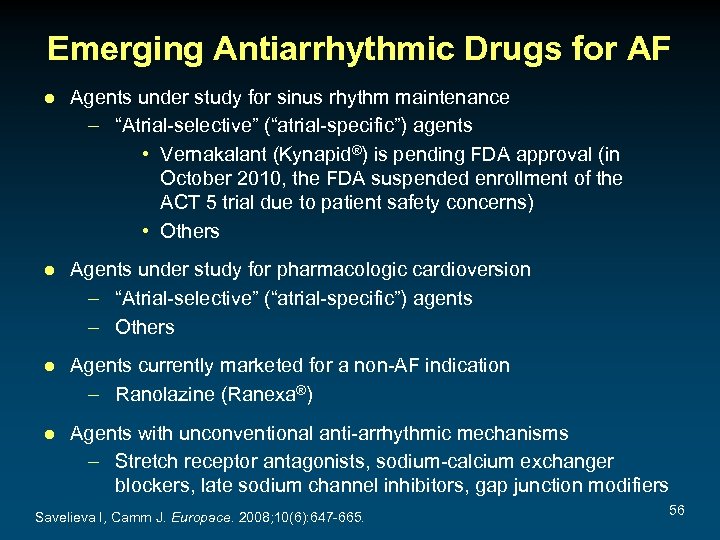

Emerging Antiarrhythmic Drugs for AF ● Agents under study for sinus rhythm maintenance – “Atrial-selective” (“atrial-specific”) agents • Vernakalant (Kynapid®) is pending FDA approval (in October 2010, the FDA suspended enrollment of the ACT 5 trial due to patient safety concerns) • Others ● Agents under study for pharmacologic cardioversion – “Atrial-selective” (“atrial-specific”) agents – Others ● Agents currently marketed for a non-AF indication – Ranolazine (Ranexa®) ● Agents with unconventional anti-arrhythmic mechanisms – Stretch receptor antagonists, sodium-calcium exchanger blockers, late sodium channel inhibitors, gap junction modifiers Savelieva I, Camm J. Europace. 2008; 10(6): 647 -665. 56

Preventing Thromboembolism 57

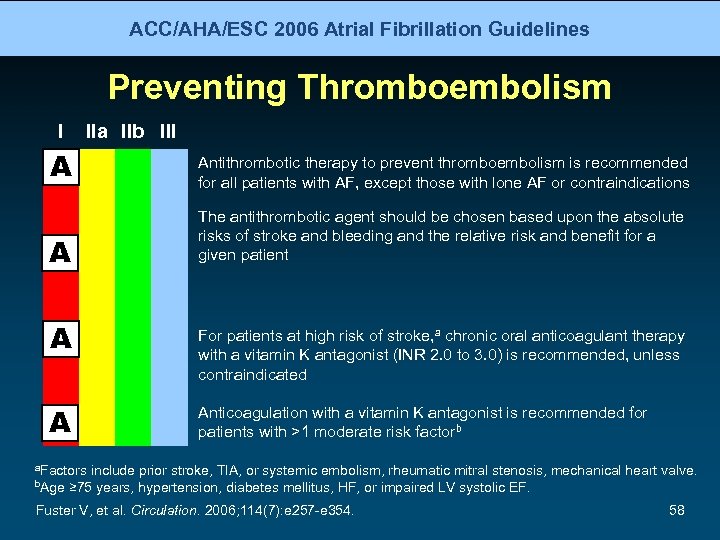

ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Atrial Fibrillation Guidelines Preventing Thromboembolism I IIa IIb III A Antithrombotic therapy to prevent thromboembolism is recommended for all patients with AF, except those with lone AF or contraindications A The antithrombotic agent should be chosen based upon the absolute risks of stroke and bleeding and the relative risk and benefit for a given patient A A For patients at high risk of stroke, a chronic oral anticoagulant therapy with a vitamin K antagonist (INR 2. 0 to 3. 0) is recommended, unless contraindicated Anticoagulation with a vitamin K antagonist is recommended for patients with >1 moderate risk factorb a. Factors b. Age include prior stroke, TIA, or systemic embolism, rheumatic mitral stenosis, mechanical heart valve. ≥ 75 years, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, HF, or impaired LV systolic EF. Fuster V, et al. Circulation. 2006; 114(7): e 257 -e 354. 58

ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Atrial Fibrillation Guidelines Preventing Thromboembolism (cont) I IIa IIb III A INR should be determined at least weekly during initiation of therapy and monthly when stable A Aspirin, 81 -325 mg daily, is recommended in low-risk patients or in those with contraindications to oral anticoagulation B For patients with mechanical heart valves, the target intensity of anticoagulation should be based on the type of prosthesis, maintaining an INR of at least 2. 5 C Antithrombotic therapy is recommended for patients with atrial flutter as for AF C Long-term anticoagulation is not recommended for primary stroke prevention in patients <60 years without heart disease (lone AF) Fuster V, et al. Circulation. 2006; 114(7): e 257 -e 354. 59

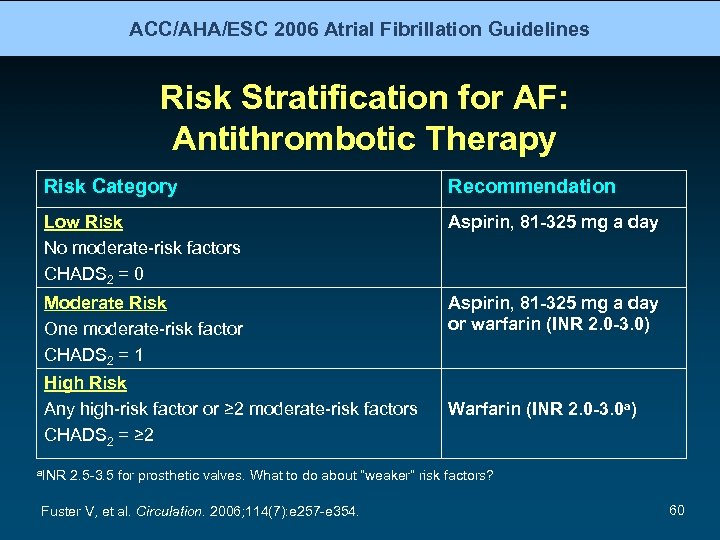

ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Atrial Fibrillation Guidelines Risk Stratification for AF: Antithrombotic Therapy Risk Category Recommendation Low Risk No moderate-risk factors CHADS 2 = 0 Aspirin, 81 -325 mg a day Moderate Risk One moderate-risk factor CHADS 2 = 1 Aspirin, 81 -325 mg a day or warfarin (INR 2. 0 -3. 0) High Risk Any high-risk factor or ≥ 2 moderate-risk factors CHADS 2 = ≥ 2 a. INR Warfarin (INR 2. 0 -3. 0 a) 2. 5 -3. 5 for prosthetic valves. What to do about “weaker” risk factors? Fuster V, et al. Circulation. 2006; 114(7): e 257 -e 354. 60

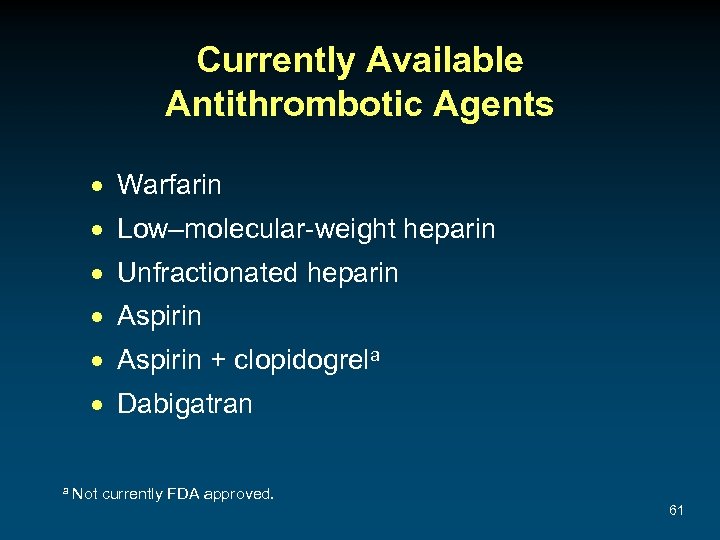

Currently Available Antithrombotic Agents · Warfarin · Low–molecular-weight heparin · Unfractionated heparin · Aspirin + clopidogrela · Dabigatran a Not currently FDA approved. 61

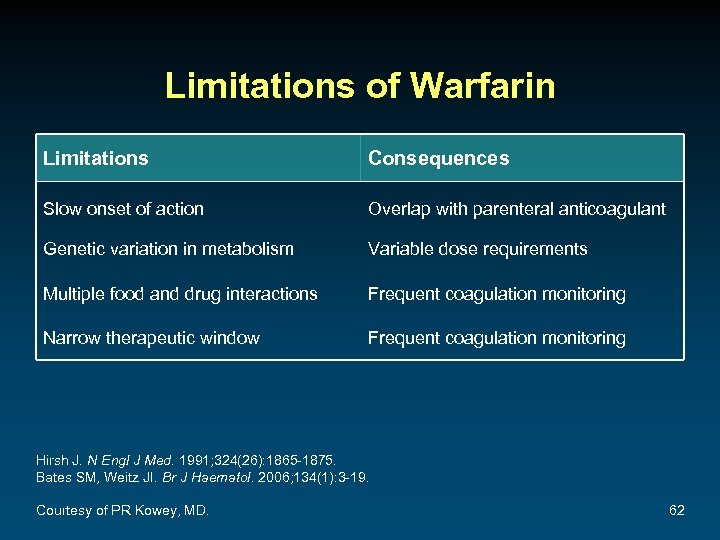

Limitations of Warfarin Limitations Consequences Slow onset of action Overlap with parenteral anticoagulant Genetic variation in metabolism Variable dose requirements Multiple food and drug interactions Frequent coagulation monitoring Narrow therapeutic window Frequent coagulation monitoring Hirsh J. N Engl J Med. 1991; 324(26): 1865 -1875. Bates SM, Weitz JI. Br J Haematol. 2006; 134(1): 3 -19. Courtesy of PR Kowey, MD. 62

The ACTIVE Studies ACTIVE-W 1 – Compared warfarin (INR, 2 -3) vs clopidogrel 75 mg/d + ASA – – (75 -100 mg/d) in high-risk AF patients 6706 patients randomized 1. 28 years of follow-up Primary end point: stroke, systemic embolus, MI, vascular death Study stopped early due to superiority of warfarin ACTIVE-A 2 – Compared clopidogrel 75 mg/d + ASA (75 -100 mg/d) vs ASA alone in – – high-risk AF patients who could not or would not take warfarin 7554 patients randomized Same primary end point 3. 6 years of follow-up Stroke occurred in 296 (2. 4%/y) patients on clopidogrel + ASA and in 408 patients (3. 3%/y) on ASA alone (RR, 0. 72; P<. 001). However, major bleeding occurred in 251 (2. 0%/y) patients on clopidogrel + ASA and in 162 (1. 3%/y) patients on ASA alone (RR, 1. 57; P<. 001) 1. ACTIVE Investigators. Lancet. 2006; 367(9526): 1903 -1912. 2. ACTIVE Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360(20): 2066 -2078. 63

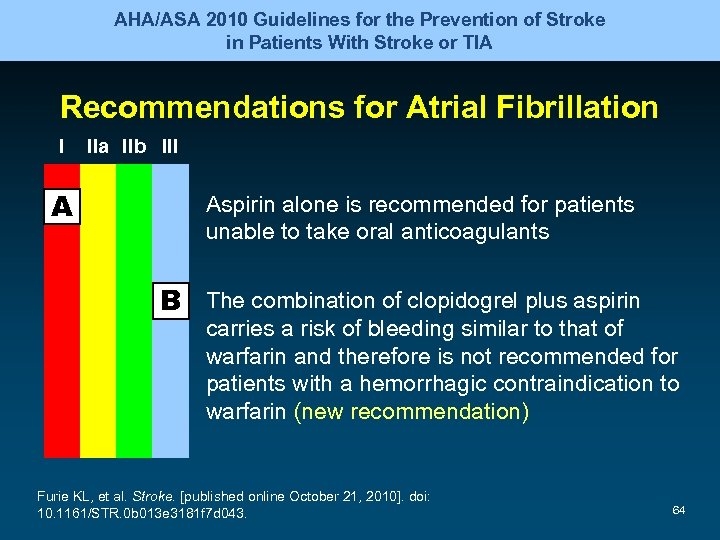

AHA/ASA 2010 Guidelines for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Stroke or TIA Recommendations for Atrial Fibrillation I A IIa IIb III Aspirin alone is recommended for patients unable to take oral anticoagulants B The combination of clopidogrel plus aspirin carries a risk of bleeding similar to that of warfarin and therefore is not recommended for patients with a hemorrhagic contraindication to warfarin (new recommendation) Furie KL, et al. Stroke. [published online October 21, 2010]. doi: 10. 1161/STR. 0 b 013 e 3181 f 7 d 043. 64

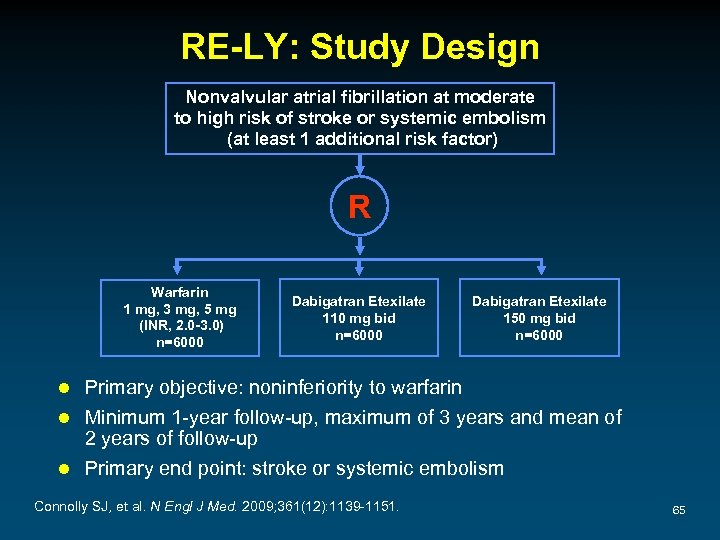

RE-LY: Study Design Nonvalvular atrial fibrillation at moderate to high risk of stroke or systemic embolism (at least 1 additional risk factor) R Warfarin 1 mg, 3 mg, 5 mg (INR, 2. 0 -3. 0) n=6000 Dabigatran Etexilate 110 mg bid n=6000 Dabigatran Etexilate 150 mg bid n=6000 Primary objective: noninferiority to warfarin l Minimum 1 -year follow-up, maximum of 3 years and mean of 2 years of follow-up l Primary end point: stroke or systemic embolism l Connolly SJ, et al. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361(12): 1139 -1151. 65

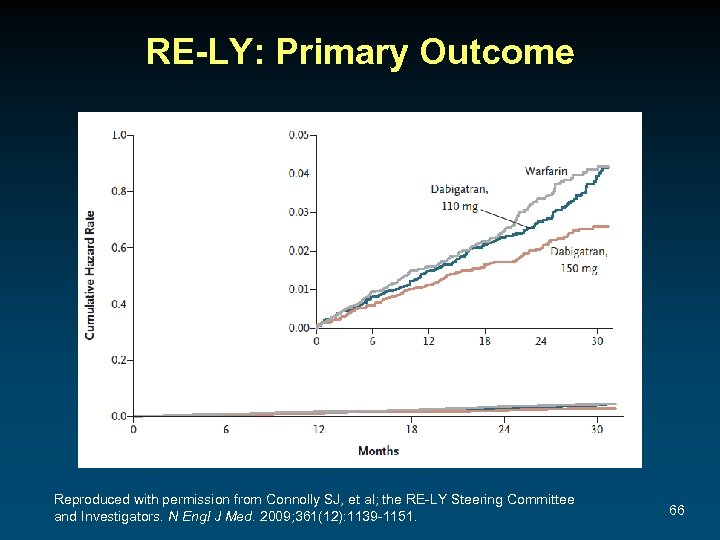

RE-LY: Primary Outcome Reproduced with permission from Connolly SJ, et al; the RE-LY Steering Committee and Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361(12): 1139 -1151. 66

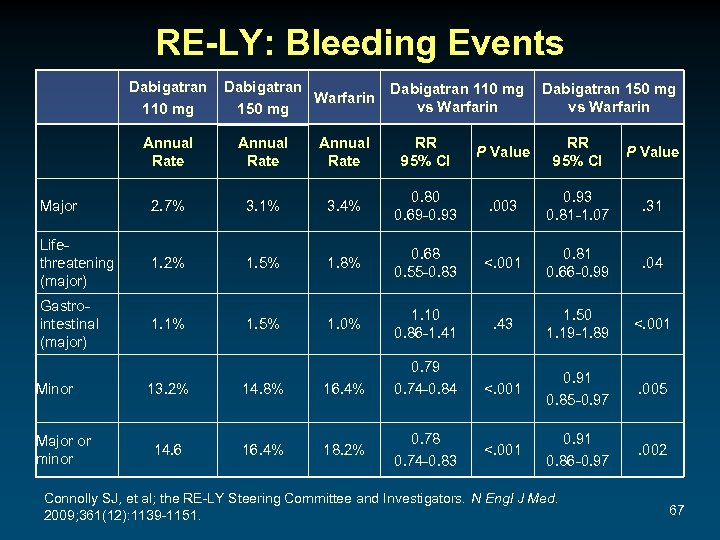

RE-LY: Bleeding Events Dabigatran 110 mg Dabigatran Warfarin 150 mg Dabigatran 110 mg vs Warfarin Dabigatran 150 mg vs Warfarin Annual Rate RR 95% CI P Value Major 2. 7% 3. 1% 3. 4% 0. 80 0. 69 -0. 93 . 003 0. 93 0. 81 -1. 07 . 31 Lifethreatening (major) 1. 2% 1. 5% 1. 8% 0. 68 0. 55 -0. 83 <. 001 0. 81 0. 66 -0. 99 . 04 Gastrointestinal (major) 1. 1% 1. 5% 1. 0% 1. 10 0. 86 -1. 41 . 43 1. 50 1. 19 -1. 89 <. 001 0. 91 0. 85 -0. 97 . 005 <. 001 0. 91 0. 86 -0. 97 . 002 Minor Major or minor 13. 2% 14. 8% 16. 4% 14. 6 16. 4% 18. 2% 0. 79 0. 74 -0. 84 0. 78 0. 74 -0. 83 Connolly SJ, et al; the RE-LY Steering Committee and Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361(12): 1139 -1151. 67

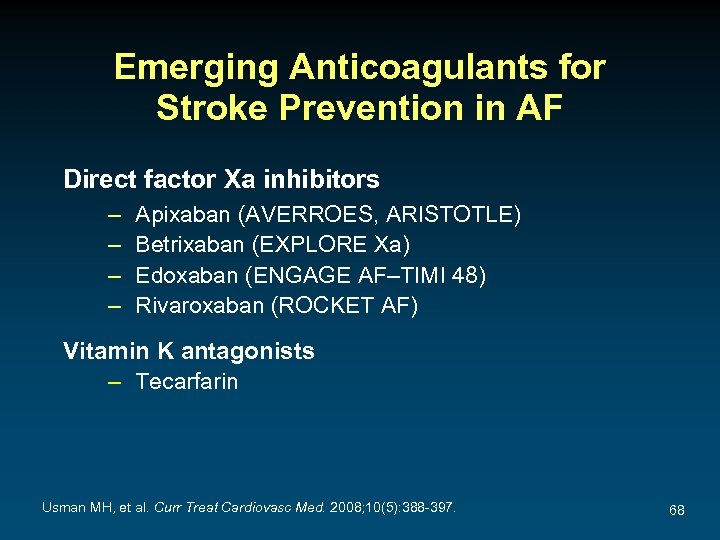

Emerging Anticoagulants for Stroke Prevention in AF Direct factor Xa inhibitors – – Apixaban (AVERROES, ARISTOTLE) Betrixaban (EXPLORE Xa) Edoxaban (ENGAGE AF–TIMI 48) Rivaroxaban (ROCKET AF) Vitamin K antagonists – Tecarfarin Usman MH, et al. Curr Treat Cardiovasc Med. 2008; 10(5): 388 -397. 68

Case: 65 -Year-Old Man With Recent Episodes of Palpitations, Weakness, and Lightheadedness Scheduled Follow-up Visit at 4 Weeks ● The patient continues to take dronedarone as prescribed ● His ECG shows sinus rhythm without other abnormalities ● He reports no side effects from the medication; however, he continues to experience episodes of AF 2 to 3 times per week that last several hours at a time, and complains of severe palpitations and fatigue during the AF episodes 69

Case: 65 -Year-Old Man With Recent Episodes of Palpitations, Weakness, and Lightheadedness What treatment would you now suggest? A. B. C. D. E. Catheter ablation Flecainide Dofetilide Amiodarone AV node ablation and PPM 70

Surgical and Catheter Ablation 71

HRS/EHRA/ECAS 2007 Expert Consensus Statement on Catheter and Surgical Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation Indications for Surgical Ablation ● Symptomatic AF patients undergoing other cardiac surgery ● Selected asymptomatic AF patients undergoing cardiac surgery in whom the ablation can be performed with minimal risk ● Symptomatic AF patients who prefer a surgical approach, have failed 1 or more attempts at catheter ablation, or are not candidates for catheter ablation Best results are obtained in patients with paroxysmal AF who are young and otherwise healthy Calkins H, et al; Heart Rhythm Society Task Force on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2007; 4(6): 816 -861. 72

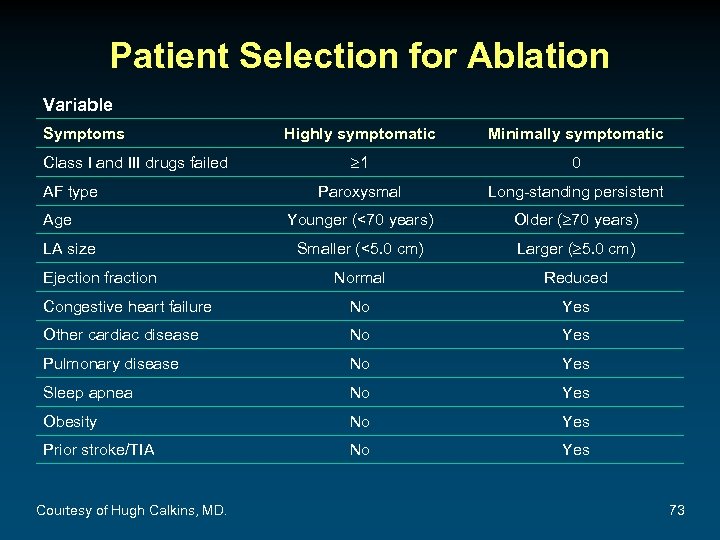

Patient Selection for Ablation Variable Symptoms Highly symptomatic Minimally symptomatic 1 0 Paroxysmal Long-standing persistent Younger (<70 years) Older ( 70 years) Smaller (<5. 0 cm) Larger ( 5. 0 cm) Normal Reduced Congestive heart failure No Yes Other cardiac disease No Yes Pulmonary disease No Yes Sleep apnea No Yes Obesity No Yes Prior stroke/TIA No Yes Class I and III drugs failed AF type Age LA size Ejection fraction Courtesy of Hugh Calkins, MD. 73

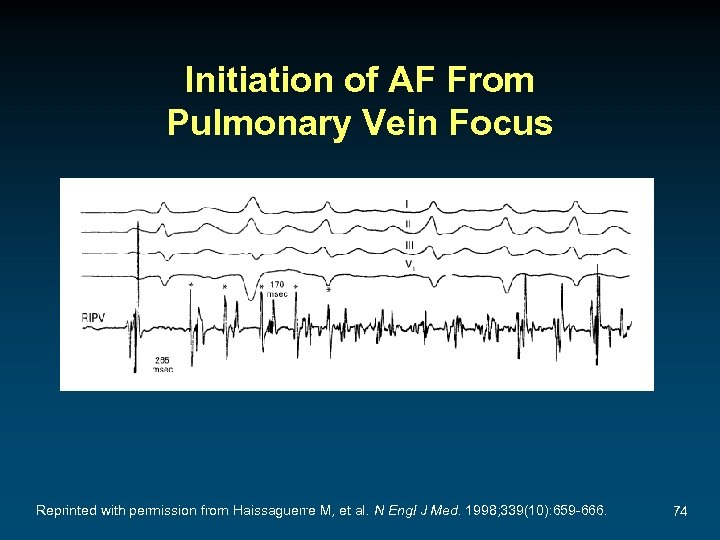

Initiation of AF From Pulmonary Vein Focus Reprinted with permission from Haissaguerre M, et al. N Engl J Med. 1998; 339(10): 659 -666. 74

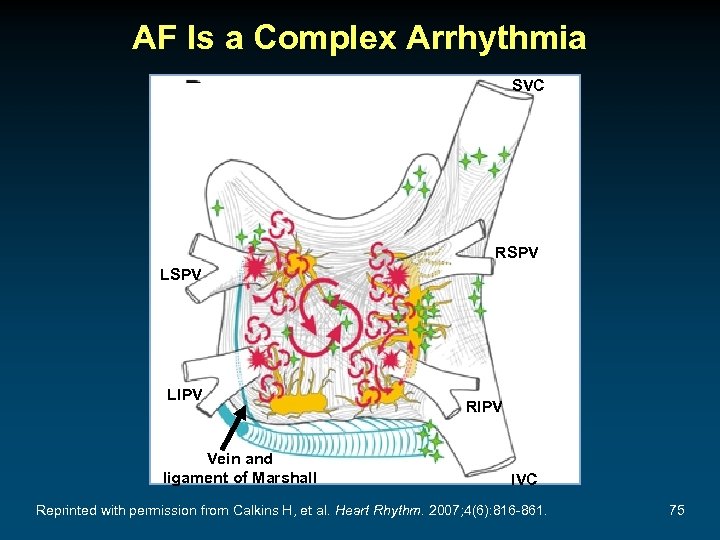

AF Is a Complex Arrhythmia SVC RSPV LIPV Vein and ligament of Marshall RIPV IVC Reprinted with permission from Calkins H, et al. Heart Rhythm. 2007; 4(6): 816 -861. 75

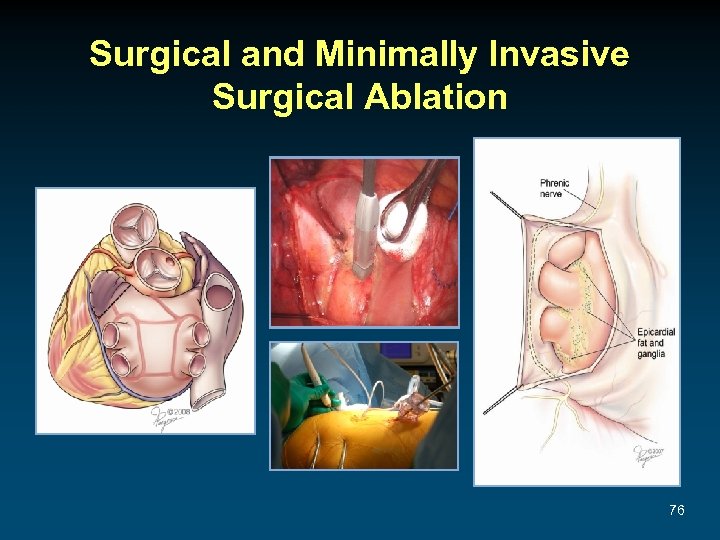

Surgical and Minimally Invasive Surgical Ablation 76

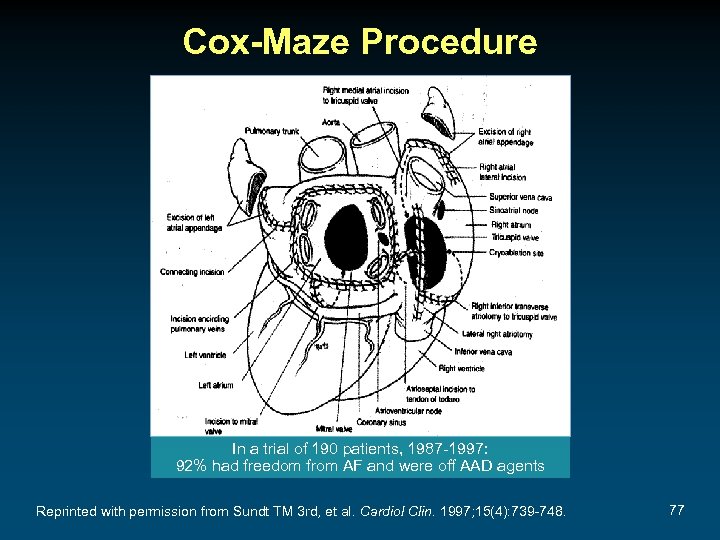

Cox-Maze Procedure In a trial of 190 patients, 1987 -1997: 92% had freedom from AF and were off AAD agents Reprinted with permission from Sundt TM 3 rd, et al. Cardiol Clin. 1997; 15(4): 739 -748. 77

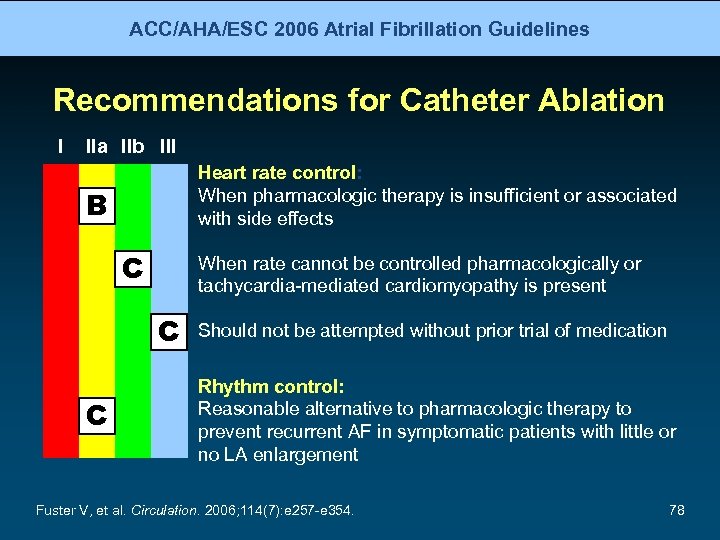

ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Atrial Fibrillation Guidelines Recommendations for Catheter Ablation I IIa IIb III Heart rate control: When pharmacologic therapy is insufficient or associated with side effects B C When rate cannot be controlled pharmacologically or tachycardia-mediated cardiomyopathy is present C C Should not be attempted without prior trial of medication Rhythm control: Reasonable alternative to pharmacologic therapy to prevent recurrent AF in symptomatic patients with little or no LA enlargement Fuster V, et al. Circulation. 2006; 114(7): e 257 -e 354. 78

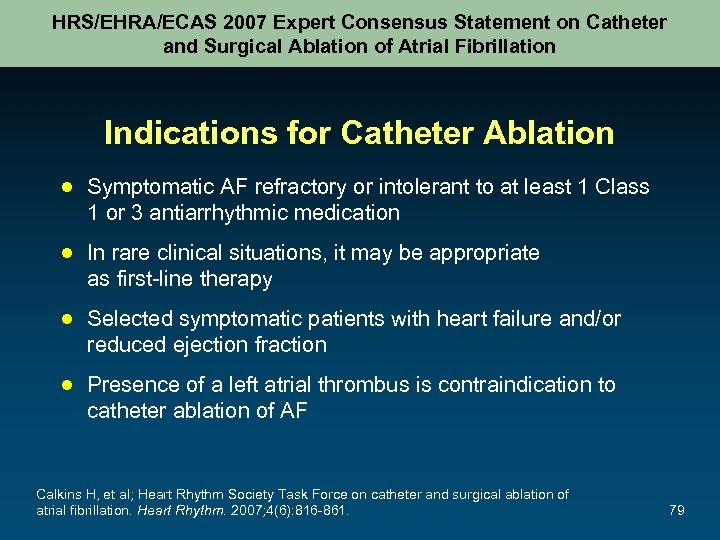

HRS/EHRA/ECAS 2007 Expert Consensus Statement on Catheter and Surgical Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation Indications for Catheter Ablation ● Symptomatic AF refractory or intolerant to at least 1 Class 1 or 3 antiarrhythmic medication ● In rare clinical situations, it may be appropriate as first-line therapy ● Selected symptomatic patients with heart failure and/or reduced ejection fraction ● Presence of a left atrial thrombus is contraindication to catheter ablation of AF Calkins H, et al; Heart Rhythm Society Task Force on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2007; 4(6): 816 -861. 79

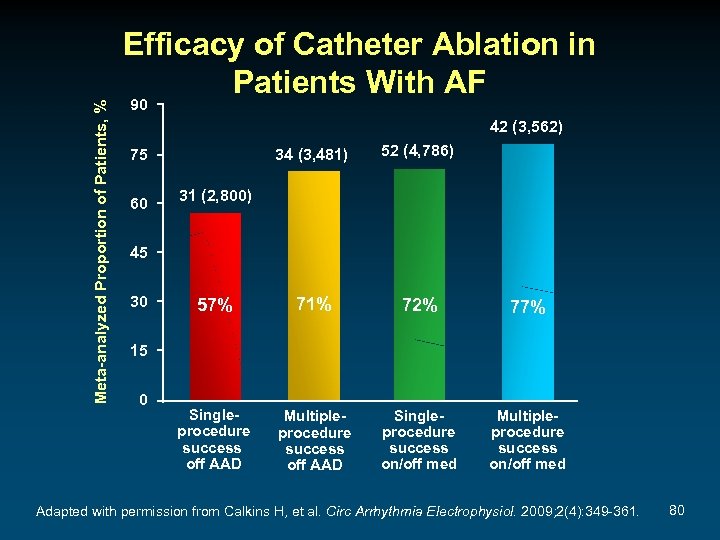

Meta-analyzed Proportion of Patients, % Efficacy of Catheter Ablation in Patients With AF 90 42 (3, 562) 34 (3, 481) 52 (4, 786) 57% 71% 72% 77% Singleprocedure success off AAD Multipleprocedure success off AAD Singleprocedure success on/off med Multipleprocedure success on/off med 75 60 31 (2, 800) 45 30 15 0 Adapted with permission from Calkins H, et al. Circ Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2009; 2(4): 349 -361. 80

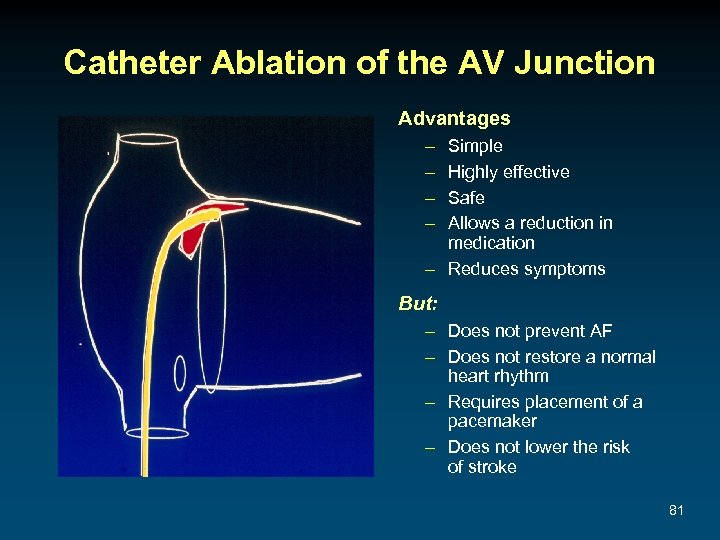

Catheter Ablation of the AV Junction Advantages – – Simple Highly effective Safe Allows a reduction in medication – Reduces symptoms But: – Does not prevent AF – Does not restore a normal heart rhythm – Requires placement of a pacemaker – Does not lower the risk of stroke 81

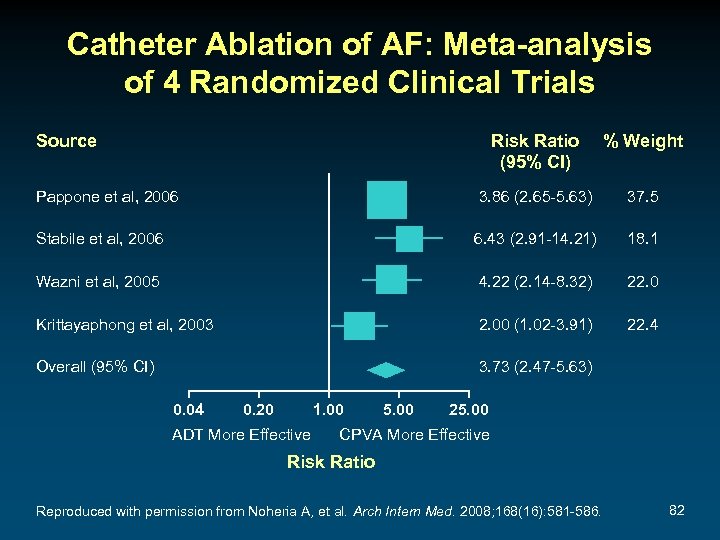

Catheter Ablation of AF: Meta-analysis of 4 Randomized Clinical Trials Source Risk Ratio (95% CI) % Weight Pappone et al, 2006 3. 86 (2. 65 -5. 63) 37. 5 Stabile et al, 2006 6. 43 (2. 91 -14. 21) 18. 1 Wazni et al, 2005 4. 22 (2. 14 -8. 32) 22. 0 Krittayaphong et al, 2003 2. 00 (1. 02 -3. 91) 22. 4 Overall (95% CI) 3. 73 (2. 47 -5. 63) 0. 04 0. 20 1. 00 ADT More Effective 5. 00 25. 00 CPVA More Effective Risk Ratio Reproduced with permission from Noheria A, et al. Arch Intern Med. 2008; 168(16): 581 -586. 82

Navi. Star® Thermo. Cool® Diagnostic/Ablation Catheter ● ● ● Steerable, multi-electrode, deflectable 3. 5 -mm tip and 3 ring electrodes 6 saline ports in the tip for irrigation and cooling (open irrigation) A location sensor and a temperature sensor incorporated into the tip Approved by the FDA on February 6, 2009, for treatment of AF 83

Freedom From AF Recurrence Thermo. Cool® Catheter vs AAD: Time to Chronic Failures 1. 0 0. 8 64% Ablation (n=103) 0. 6 P<. 001 0. 4 16% AAD (n=56) 0. 2 0. 0 0 30 60 Number of subjects at risk: 90 120 150 180 210 240 270 300 330 360 Days Into Effectiveness Follow-up Ablation 103 69 69 66 63 62 61 54 52 37 15 3 2 AAD 56 39 29 19 16 13 11 10 7 2 0 0 0 Effectiveness cohort, N=159. Circles in the graph represent 14 censored catheter ablation subjects. Wilber D. Presented at: American Heart Association 2008 Scientific Sessions; November 11, 2008; New Orleans, LA. 84

Case: 65 -Year-Old Man With Recent Episodes of Palpitations, Weakness, and Lightheadedness Catheter Ablation and Follow-up Visit at 3 Months ● The patient undergoes successful catheter ablation ● On follow-up 3 months post-catheter ablation, he is in AF and reports that AF recurred about 3 weeks following the ablation procedure and has been present constantly since that time ● He complains of continued palpitations and fatigue ● An ECG confirms the presence of AF 85

Case: 65 -Year-Old Man With Recent Episodes of Palpitations, Weakness, and Lightheadedness What treatment would you now suggest? A. B. C. D. E. F. Repeat catheter ablation Mini. Maze procedure DCC Pharmacologic cardioversion Amiodarone AV node ablation and PPM 86

Case: 65 -Year-Old Man With Recent Episodes of Palpitations, Weakness, and Lightheadedness DCC and Follow-up Visit at 6 Months Post-Catheter Ablation ● The DCC was successful in restoring sinus rhythm ● At a 6 -month follow-up visit after the catheter ablation, the patient reports 1 episode of AF each month lasting approximately 20 minutes 87

Case: 65 -Year-Old Man With Recent Episodes of Palpitations, Weakness, and Lightheadedness At this point, what treatment would you suggest? A. B. C. D. E. F. G. Repeat catheter ablation Mini. Maze procedure DCC Pharmacologic cardioversion Dronedarone AV node ablation and PPM Clinical follow-up 88

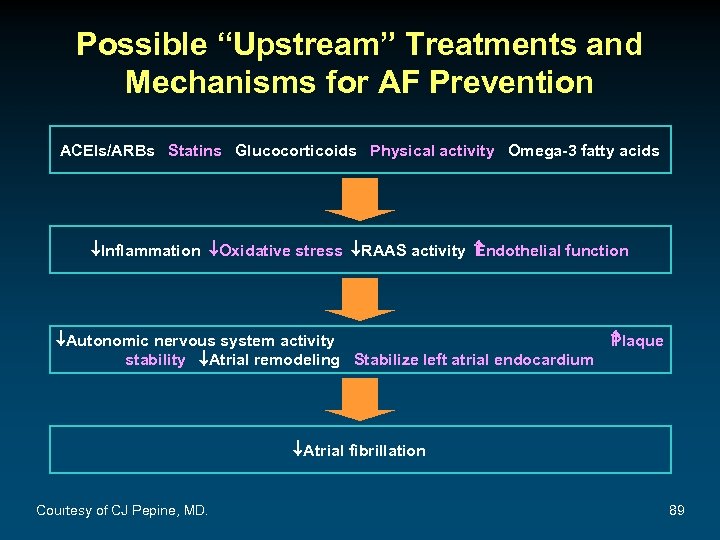

Possible “Upstream” Treatments and Mechanisms for AF Prevention ACEIs/ARBs Statins Glucocorticoids Physical activity Omega-3 fatty acids ¯Inflammation ¯Oxidative stress ¯RAAS activity ndothelial function E ¯Autonomic nervous system activity stability ¯Atrial remodeling Stabilize left atrial endocardium P laque ¯Atrial fibrillation Courtesy of CJ Pepine, MD. 89

2010 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation 90

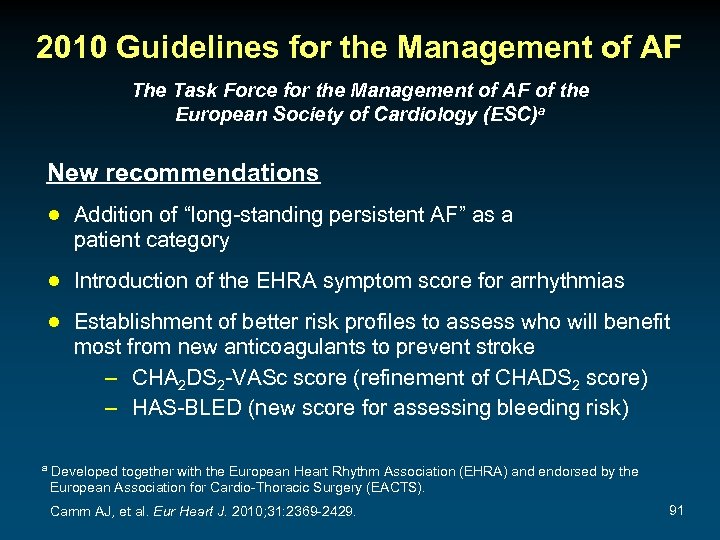

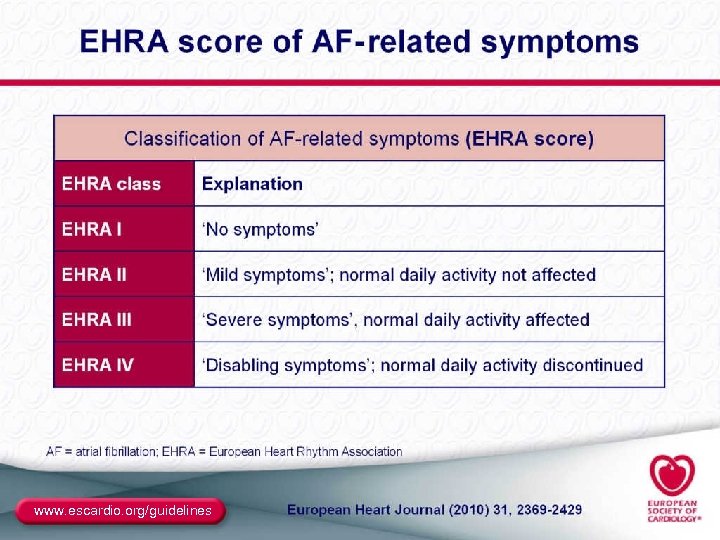

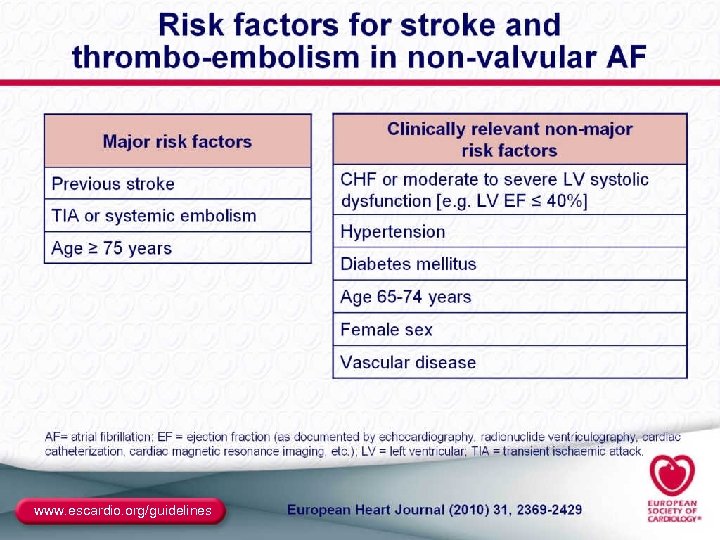

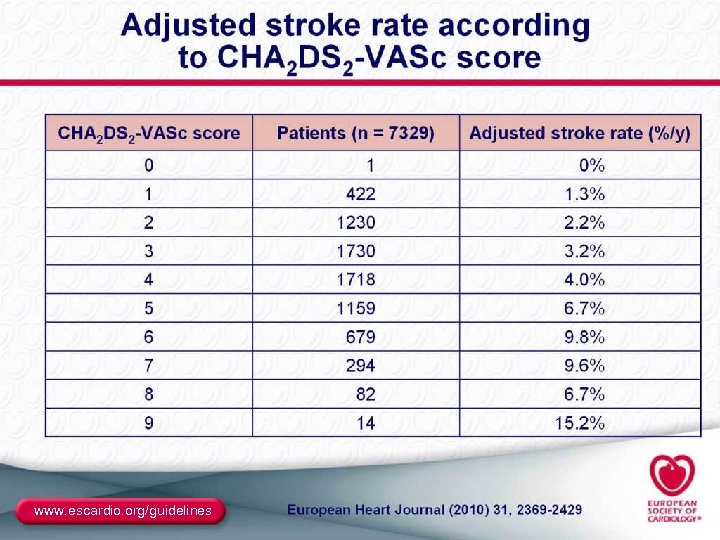

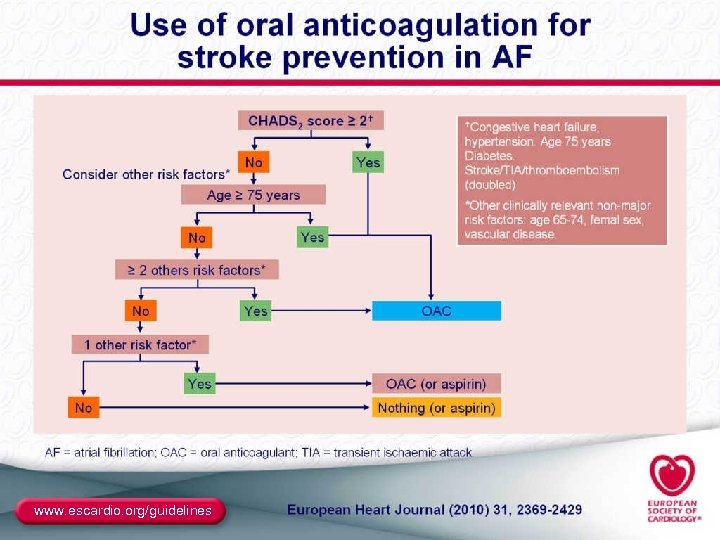

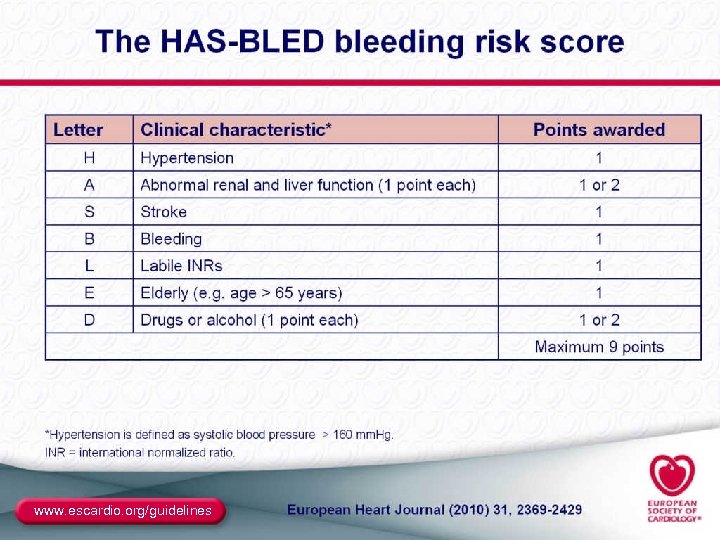

2010 Guidelines for the Management of AF The Task Force for the Management of AF of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)a New recommendations ● Addition of “long-standing persistent AF” as a patient category ● Introduction of the EHRA symptom score for arrhythmias ● Establishment of better risk profiles to assess who will benefit most from new anticoagulants to prevent stroke – CHA 2 DS 2 -VASc score (refinement of CHADS 2 score) – HAS-BLED (new score for assessing bleeding risk) a Developed together with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) and endorsed by the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Camm AJ, et al. Eur Heart J. 2010; 31: 2369 -2429. 91

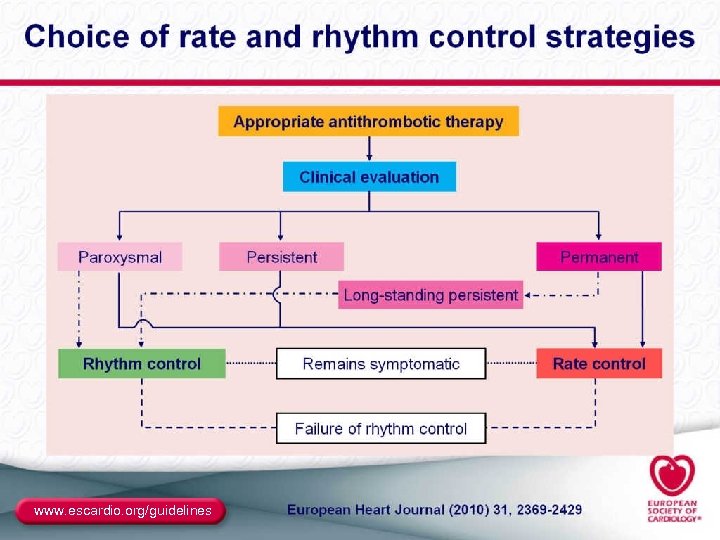

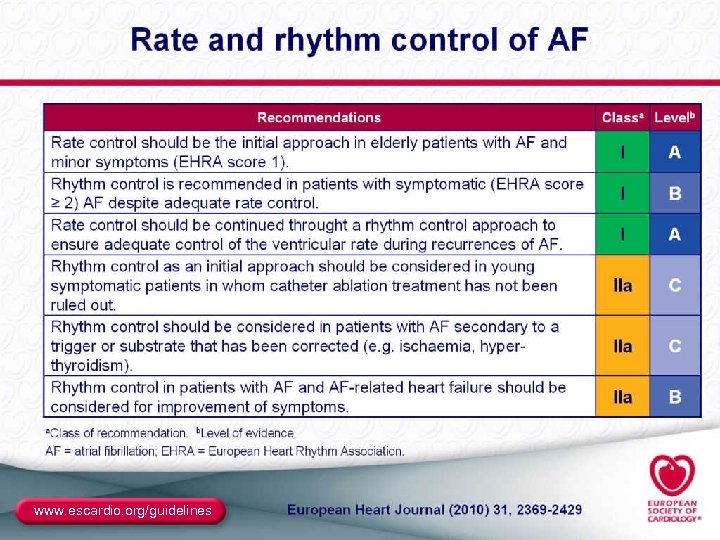

2010 Guidelines for the Management of AF (cont) The Task Force for the Management of AF of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)a Changes from the previous ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 recommendations ● New guidance in the area of rate control ● Advice on how to use the antiarrhythmic drug dronedarone ● Formal indications for the use of ablation therapy ● Recommendations on “upstream” therapies to prevent the deterioration of AF ● Advice on certain “special situations” a Developed together with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) and endorsed by the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Camm AJ, et al. Eur Heart J. 2010; 31: 2369 -2429. 92

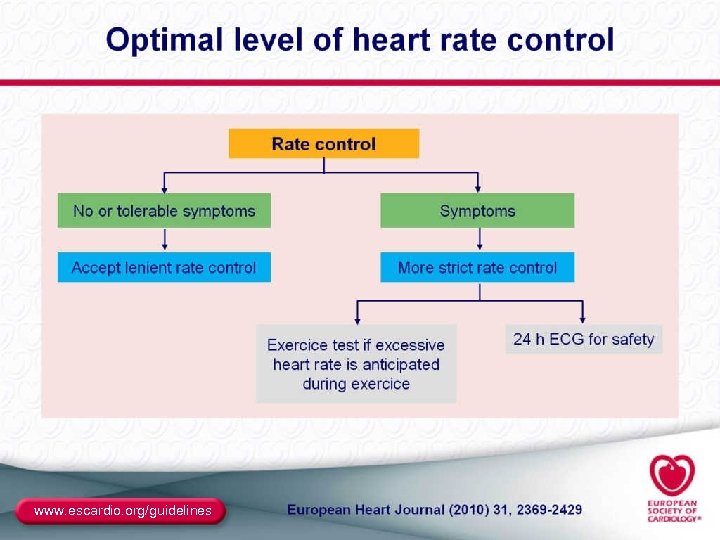

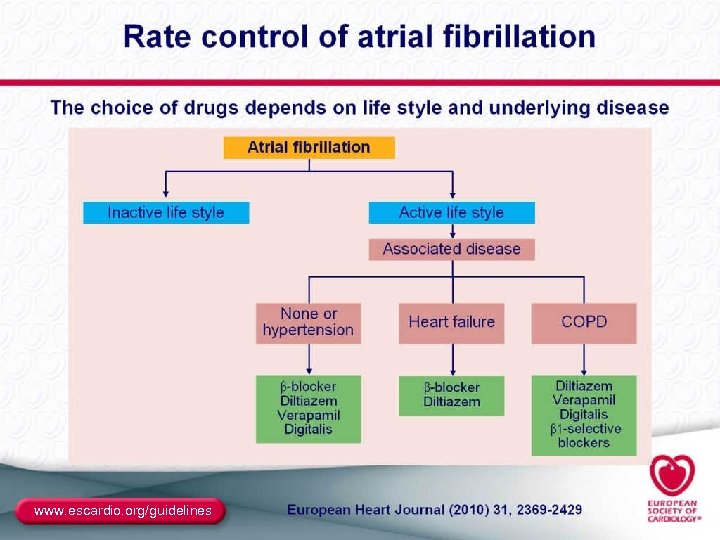

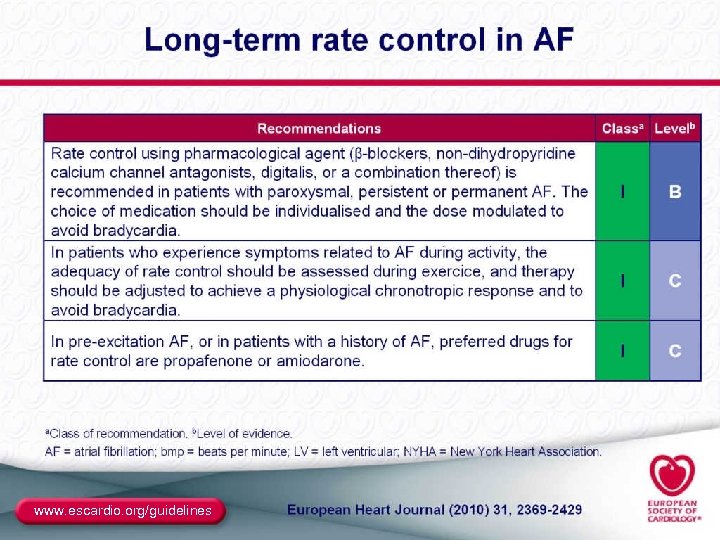

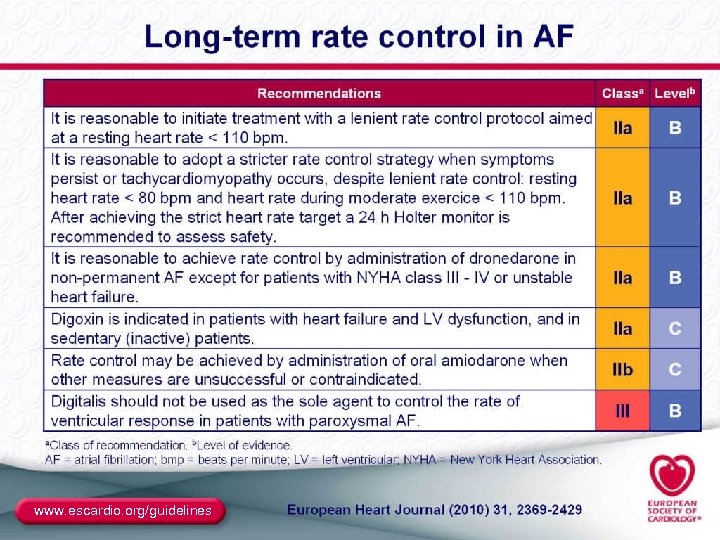

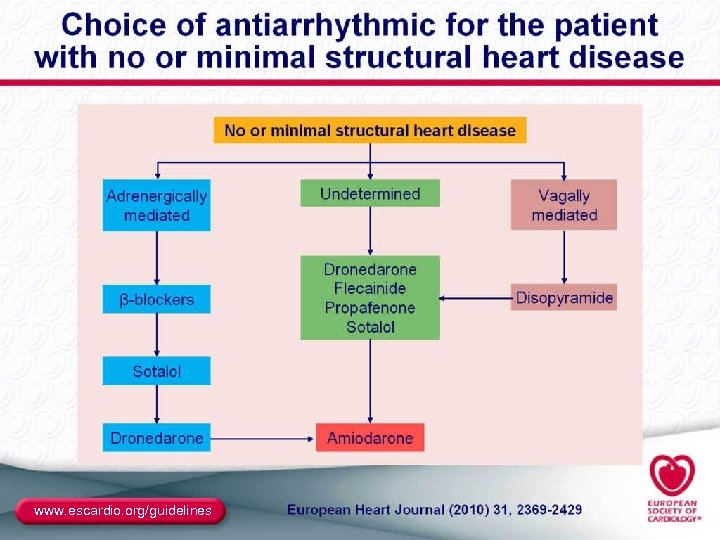

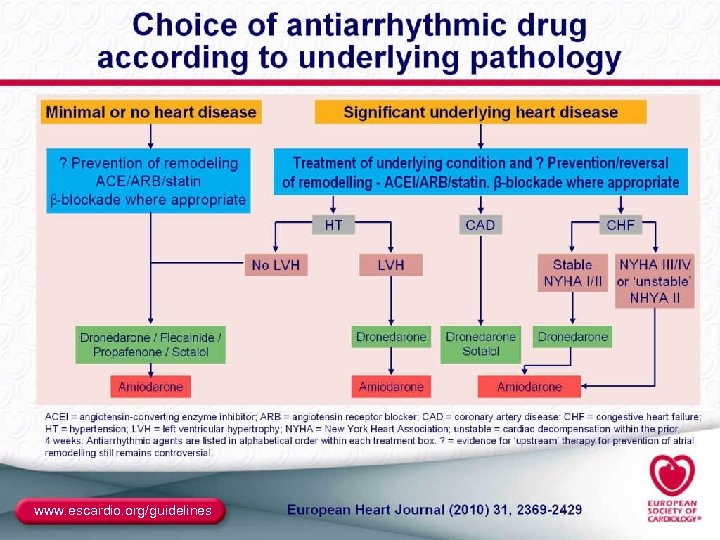

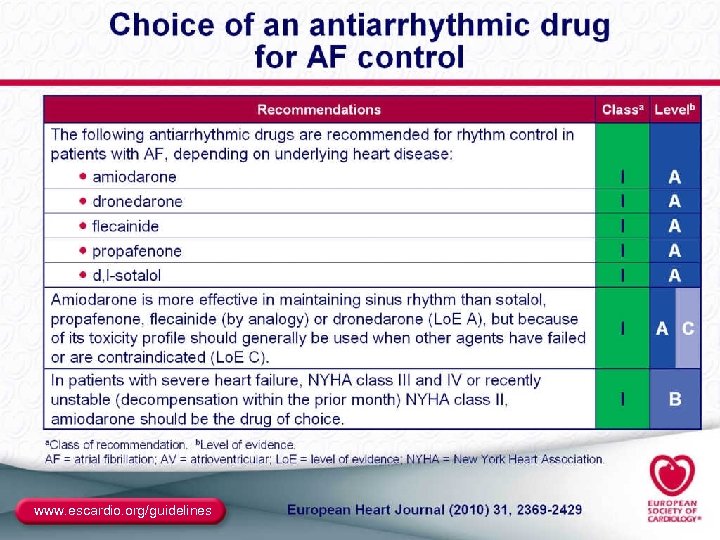

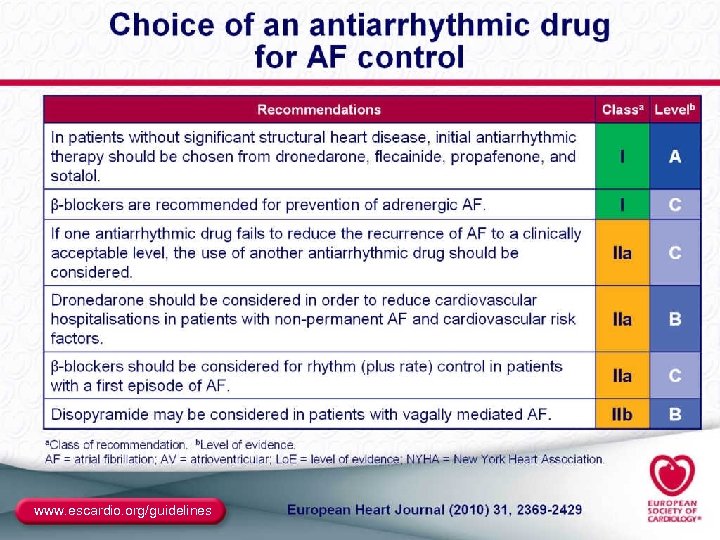

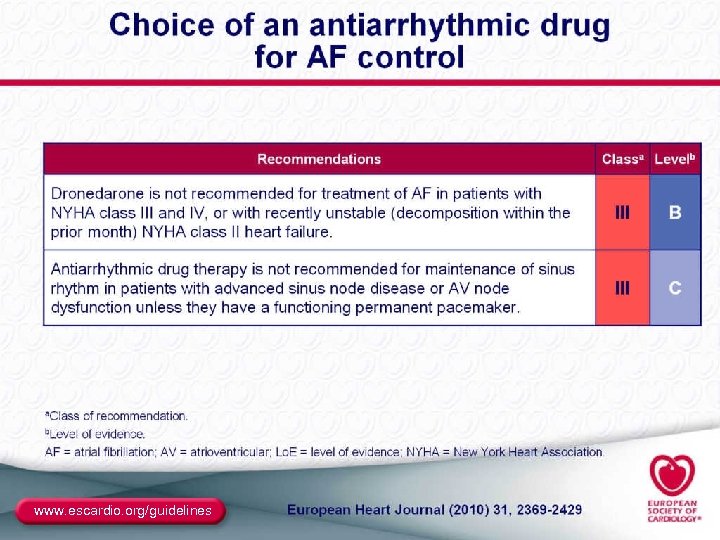

www. escardio. org/guidelines

www. escardio. org/guidelines

www. escardio. org/guidelines

www. escardio. org/guidelines

www. escardio. org/guidelines

www. escardio. org/guidelines

www. escardio. org/guidelines

www. escardio. org/guidelines

www. escardio. org/guidelines

www. escardio. org/guidelines

www. escardio. org/guidelines

www. escardio. org/guidelines

www. escardio. org/guidelines

www. escardio. org/guidelines

www. escardio. org/guidelines

www. escardio. org/guidelines

www. escardio. org/guidelines

www. escardio. org/guidelines

Question-and-Answer Session 111

AF Performance Improvement Outcomes Study ● NCME has partnered with Harvard Clinical Research Institute (HCRI) to evaluate the impact of this educational activity ● The goal of the study is to: – help each participating hospital gain perspective on how their institution manages AF – directly assess improvements in patient outcomes ● Data will be collected via a secure online Web site ● Baseline data will be collected representing a period prior to the grand rounds lecture, and then one year as a follow up ● Study closely aligns with QI programs your hospital is already involved in (eg, reporting to Joint Commission and CMS) ● $500 honorarium will be provided to each participation institution ● To sign up for the study complete the enrollment form provided to your CME coordinator or send an e-mail message to AFIBstudy@ncme. com 112

Thank you for participating! 113

1c6545ced21bcc33e3aaac34e3da92e5.ppt