c325b5cef2d82ec7646ff2fdca0bc543.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 62

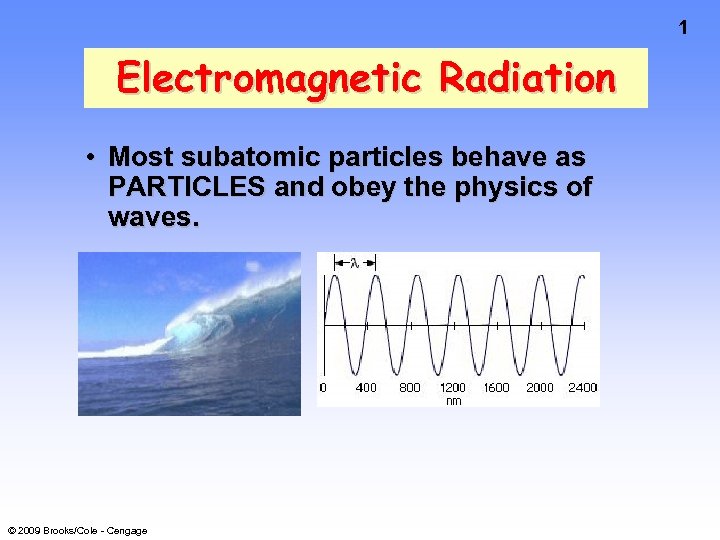

1 Electromagnetic Radiation • Most subatomic particles behave as PARTICLES and obey the physics of waves. © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage

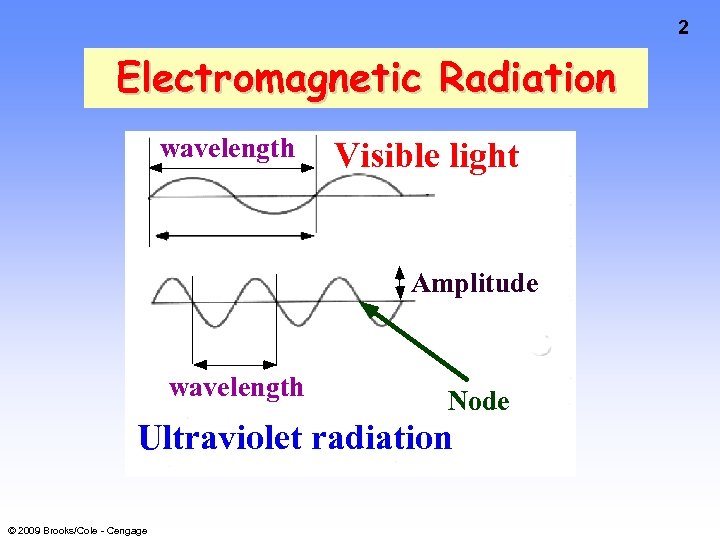

2 Electromagnetic Radiation wavelength Visible light Amplitude wavelength Node Ultraviolet radiation © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage

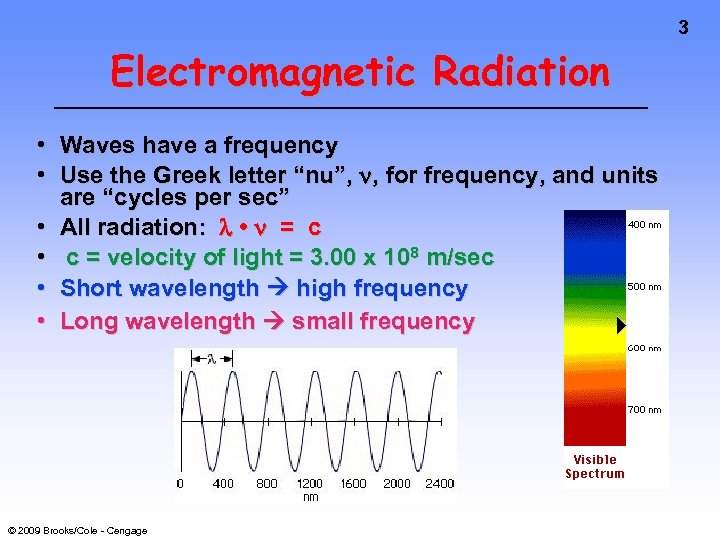

3 Electromagnetic Radiation • Waves have a frequency • Use the Greek letter “nu”, , for frequency, and units are “cycles per sec” • All radiation: • = c • c = velocity of light = 3. 00 x 108 m/sec • Short wavelength high frequency • Long wavelength small frequency © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage

4 Electromagnetic Radiation Red light has = 700 nm. Calculate the frequency. • = c © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage

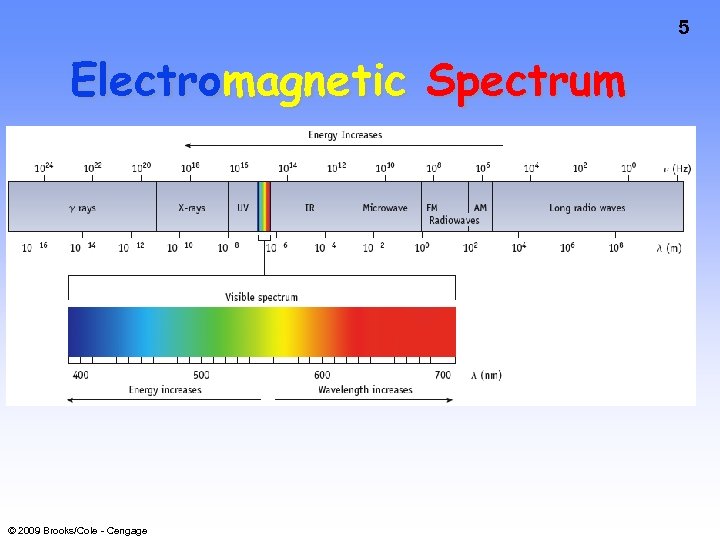

5 Electromagnetic Spectrum © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage

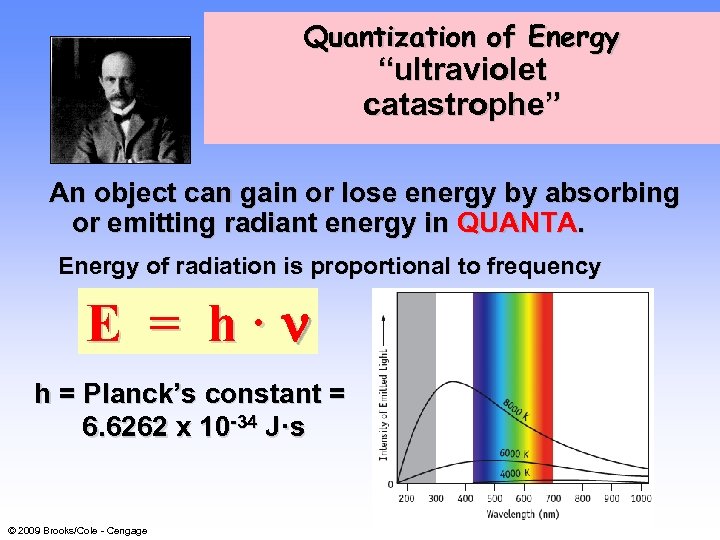

Quantization of Energy 6 “ultraviolet catastrophe” An object can gain or lose energy by absorbing or emitting radiant energy in QUANTA. Energy of radiation is proportional to frequency E = h· h = Planck’s constant = 6. 6262 x 10 -34 J·s © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage

7 Quantization of Energy E = h· Light with large (small ) has a small E. Light with a short (large ) has a large E. © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage

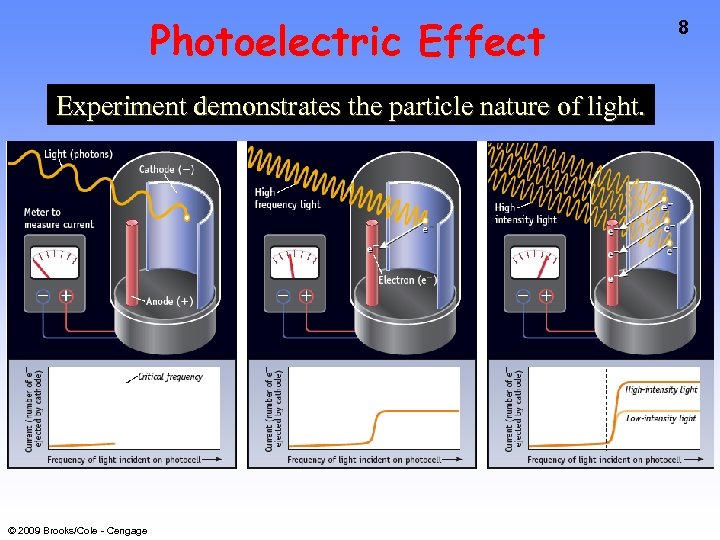

Photoelectric Effect Experiment demonstrates the particle nature of light. © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage 8

Photoelectric Effect Classical theory said that E of ejected electron should increase with increase in light intensity—not observed! • No e- observed until light of a certain minimum E is used. • Number of e- ejected depends on light intensity. © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage A. Einstein (1879 -1955) 9

Photoelectric Effect Understand experimental observations if light consists of particles called PHOTONS of discrete energy. PROBLEM: Calculate the energy of 1. 00 mol of photons of red light. = 700. nm = 4. 29 x 1014 sec-1 © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage 10

Energy of Radiation 11 Energy of 1. 00 mol of photons of red light. E = h · = (6. 63 x 10 -34 J·s)(4. 29 x 1014 s-1) = 2. 85 x 10 -19 J per photon E per mol = (2. 85 x 10 -19 J/ph)(6. 02 x 1023 ph/mol) = 172 k. J/mol This is in the range of energies that can break bonds (chapter 5) © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage

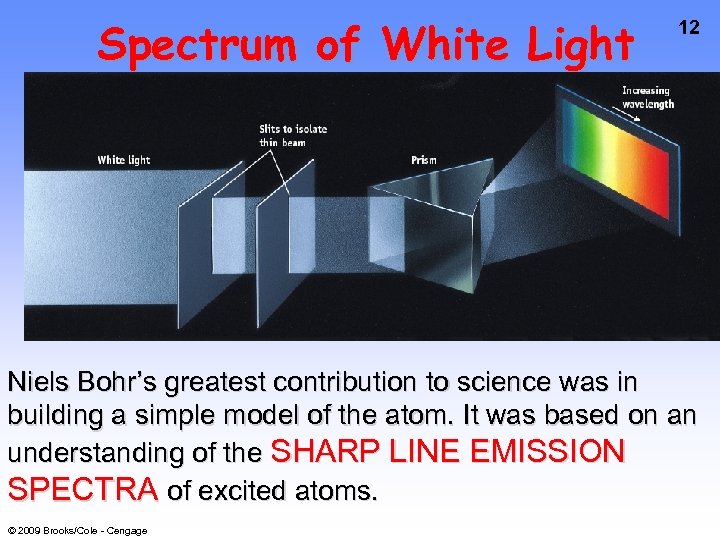

Spectrum of White Light 12 Niels Bohr’s greatest contribution to science was in building a simple model of the atom. It was based on an understanding of the SHARP LINE EMISSION SPECTRA of excited atoms. © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage

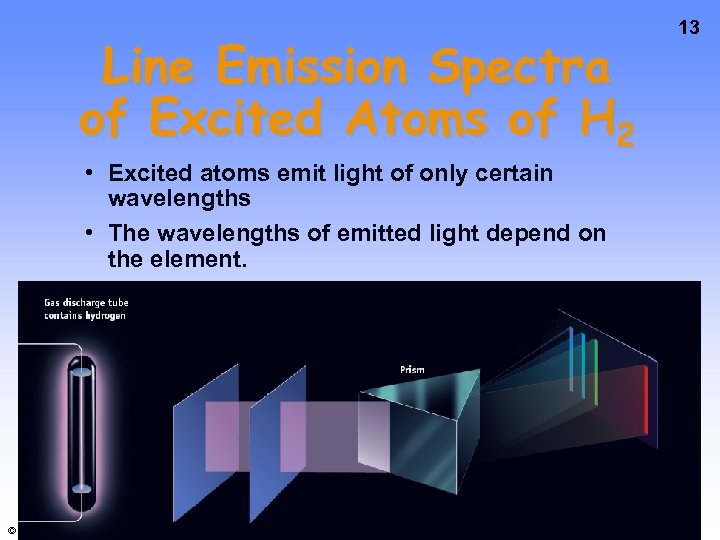

Line Emission Spectra of Excited Atoms of H 2 • Excited atoms emit light of only certain wavelengths • The wavelengths of emitted light depend on the element. © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage 13

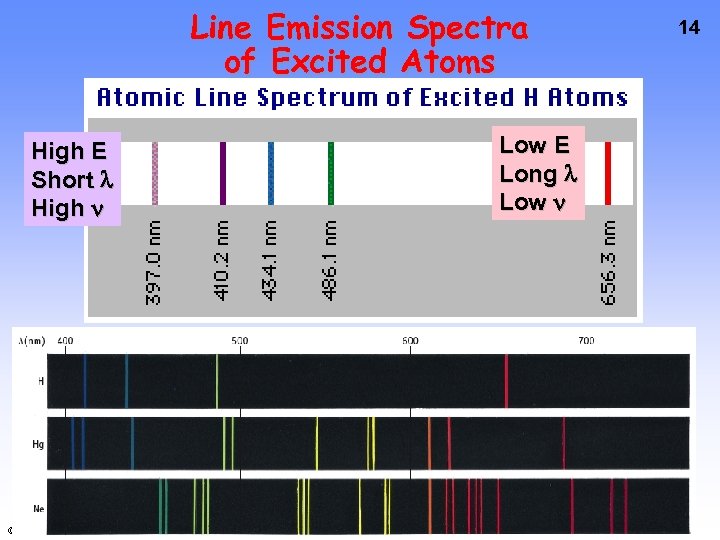

Line Emission Spectra of Excited Atoms High E Short High © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage Low E Long Low 14

15 The Electric Pickle PLAY MOVIE • Excited atoms can emit light. • Here the solution in a pickle is excited electrically. The Na+ ions in the pickle juice give off light characteristic of that element. © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage

16 Atomic Spectra and Bohr One view of atomic structure in early 20 th century was that an electron (e-) traveled about the nucleus in an orbit. 1. Any orbit should be possible and so is any energy. 2. But a charged particle moving in an electric field should emit energy. End result should be destruction! © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage

17 Atomic Spectra and Bohr said classical view is wrong. Need a new theory — now called QUANTUM or WAVE MECHANICS. e- can only exist in certain discrete orbits — called stationary states. e- is restricted to QUANTIZED energy states. Energy of state = - C/n 2 where n = quantum no. = 1, 2, 3, 4, . . © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage

18 Atomic Spectra and Bohr Energy of quantized state = - C/n 2 • Only orbits where n = integral no. are permitted. • Radius of allowed orbitals = n 2 · (0. 0529 nm) • But note — same eqns. come from modern wave mechanics approach. • Results can be used to explain atomic spectra. © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage

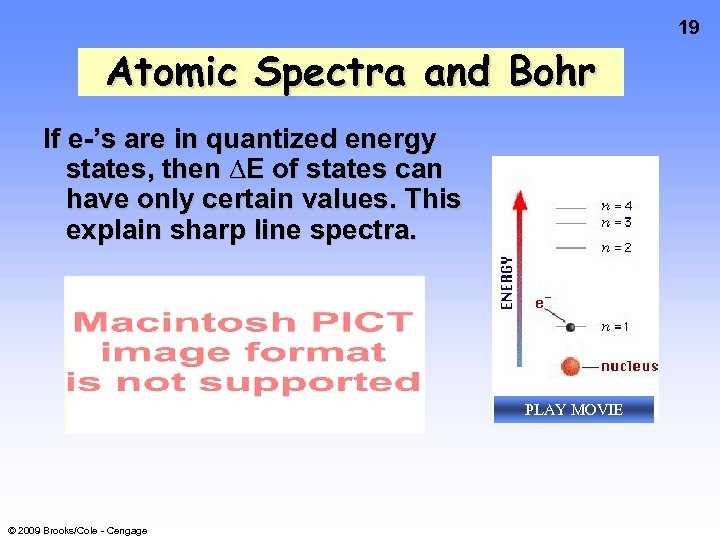

19 Atomic Spectra and Bohr If e-’s are in quantized energy states, then ∆E of states can have only certain values. This explain sharp line spectra. PLAY MOVIE © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage

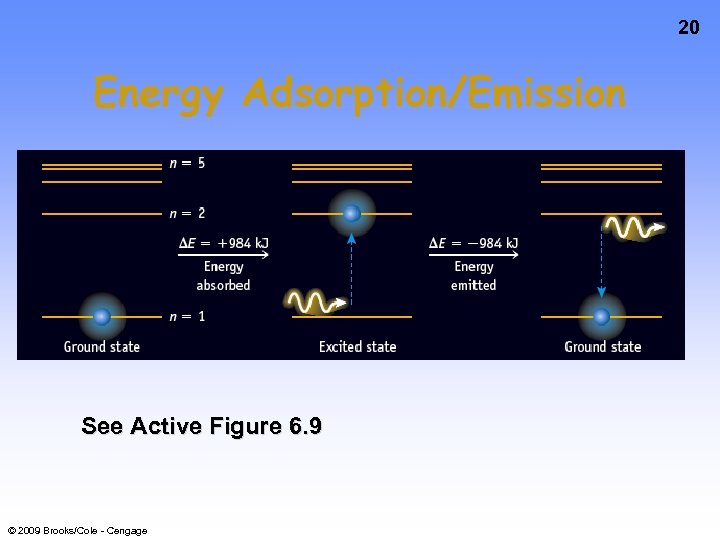

20 Energy Adsorption/Emission See Active Figure 6. 9 © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage

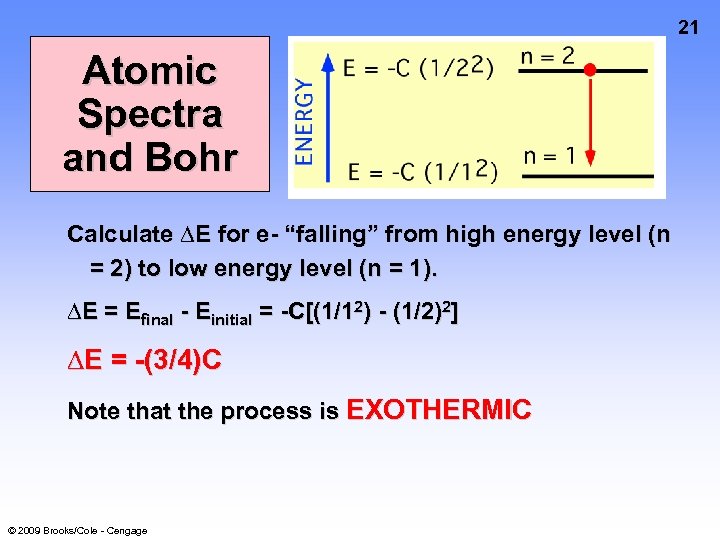

21 Atomic Spectra and Bohr Calculate ∆E for e- “falling” from high energy level (n = 2) to low energy level (n = 1). ∆E = Efinal - Einitial = -C[(1/12) - (1/2)2] ∆E = -(3/4)C Note that the process is EXOTHERMIC © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage

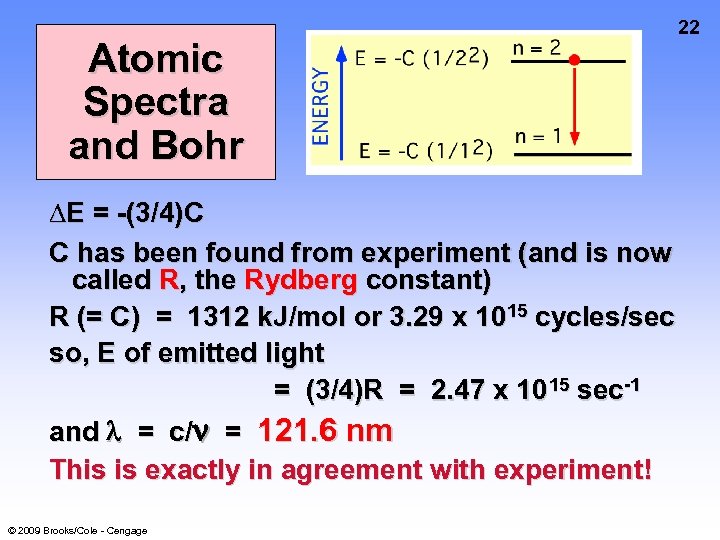

Atomic Spectra and Bohr ∆E = -(3/4)C C has been found from experiment (and is now called R, the Rydberg constant) R (= C) = 1312 k. J/mol or 3. 29 x 1015 cycles/sec so, E of emitted light = (3/4)R = 2. 47 x 10 15 sec-1 and = c/ = 121. 6 nm This is exactly in agreement with experiment! © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage 22

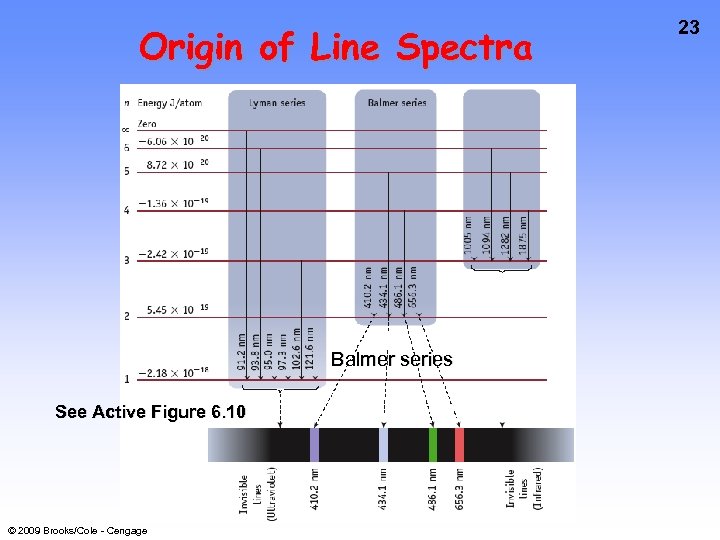

Origin of Line Spectra Balmer series See Active Figure 6. 10 © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage 23

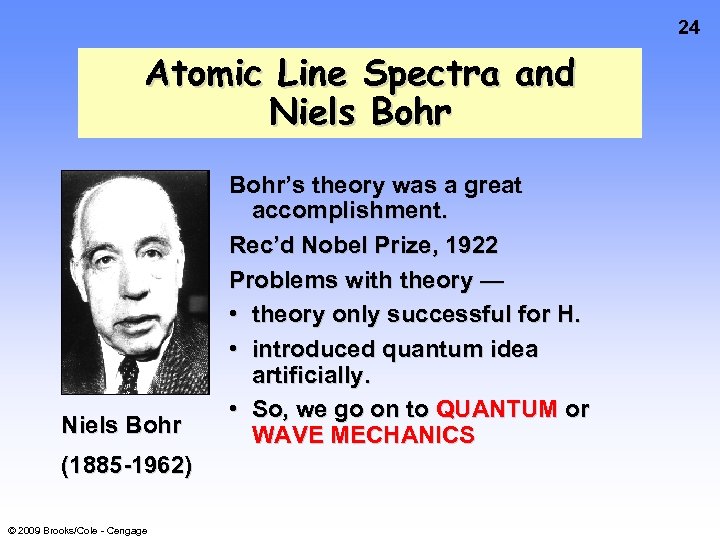

24 Atomic Line Spectra and Niels Bohr (1885 -1962) © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage Bohr’s theory was a great accomplishment. Rec’d Nobel Prize, 1922 Problems with theory — • theory only successful for H. • introduced quantum idea artificially. • So, we go on to QUANTUM or WAVE MECHANICS

25 Quantum or Wave Mechanics L. de Broglie (1892 -1987) © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage de Broglie (1924) proposed that all moving objects have wave properties. For light: E = mc 2 E = hc / Therefore, mc = h / and for particles (mass)(velocity) = h /

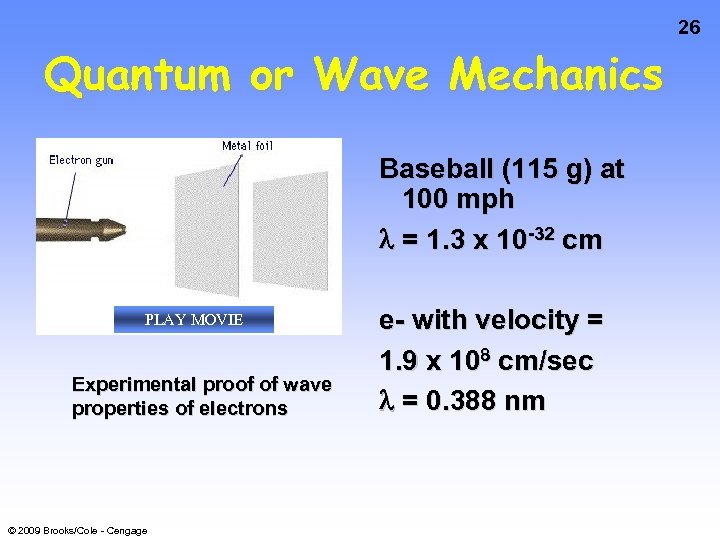

26 Quantum or Wave Mechanics Baseball (115 g) at 100 mph = 1. 3 x 10 -32 cm PLAY MOVIE Experimental proof of wave properties of electrons © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage e- with velocity = 1. 9 x 108 cm/sec = 0. 388 nm

Quantum or Wave Mechanics 27 Schrodinger applied idea of ebehaving as a wave to the problem of electrons in atoms. He developed the WAVE EQUATION Solution gives set of math expressions called WAVE FUNCTIONS, E. Schrodinger Each describes an allowed energy 1887 -1961 state of an e. Quantization introduced naturally. © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage

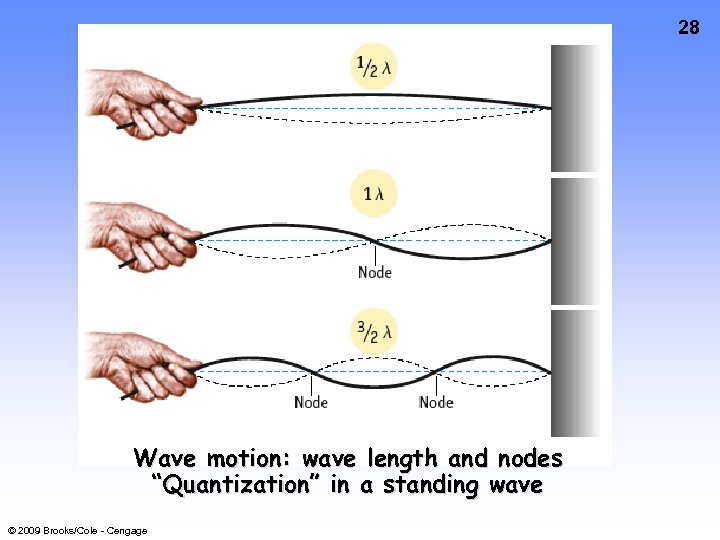

28 Wave motion: wave length and nodes “Quantization” in a standing wave © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage

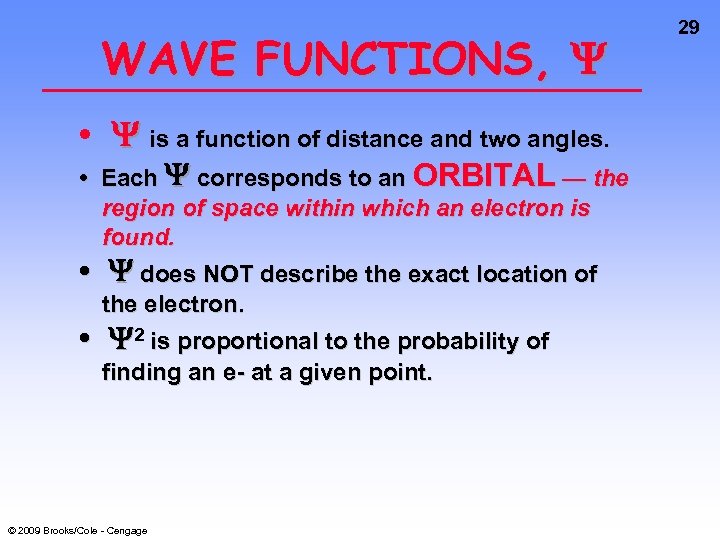

WAVE FUNCTIONS, • is a function of distance and two angles. • Each corresponds to an ORBITAL — the region of space within which an electron is found. • does NOT describe the exact location of the electron. • 2 is proportional to the probability of finding an e- at a given point. © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage 29

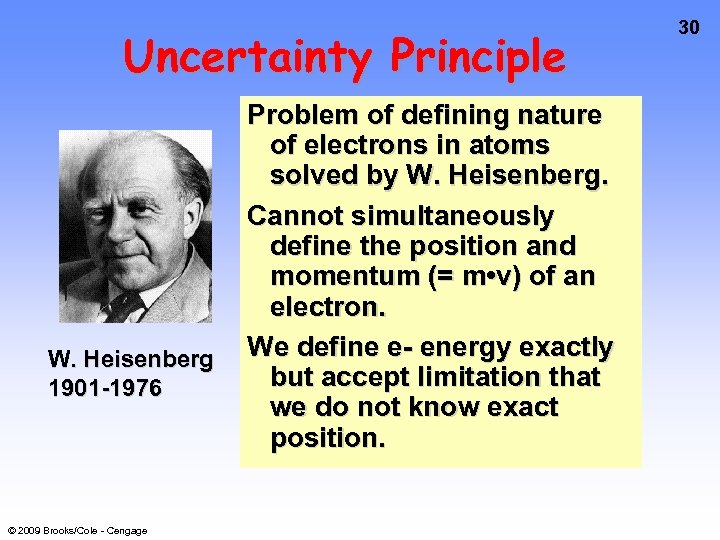

Uncertainty Principle W. Heisenberg 1901 -1976 © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage Problem of defining nature of electrons in atoms solved by W. Heisenberg. Cannot simultaneously define the position and momentum (= m • v) of an electron. We define e- energy exactly but accept limitation that we do not know exact position. 30

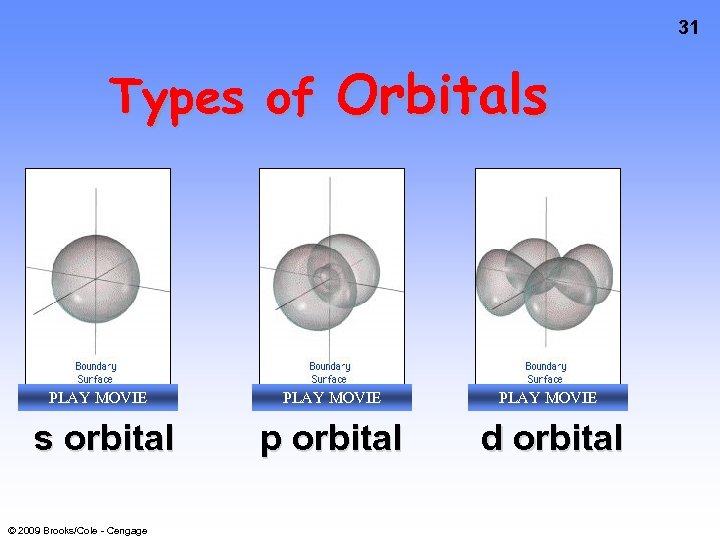

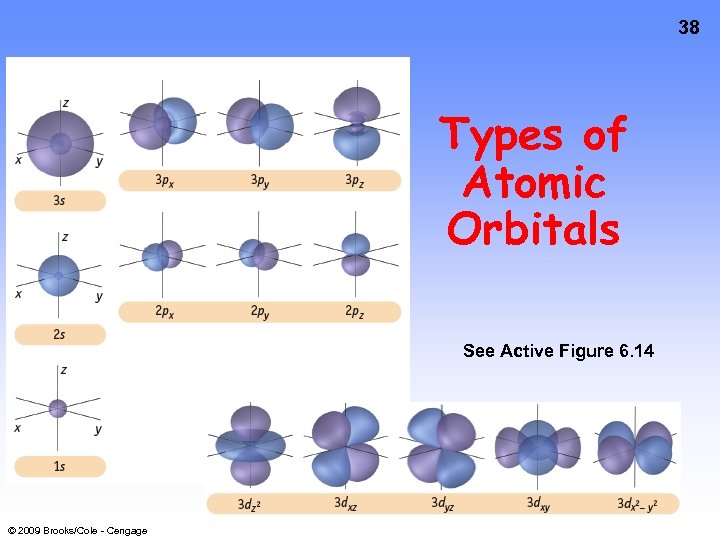

31 Types of Orbitals PLAY MOVIE s orbital © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage PLAY MOVIE p orbital PLAY MOVIE d orbital

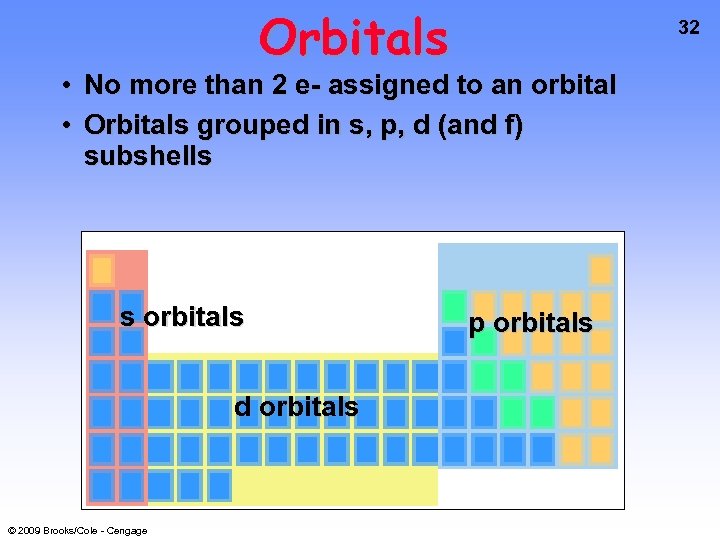

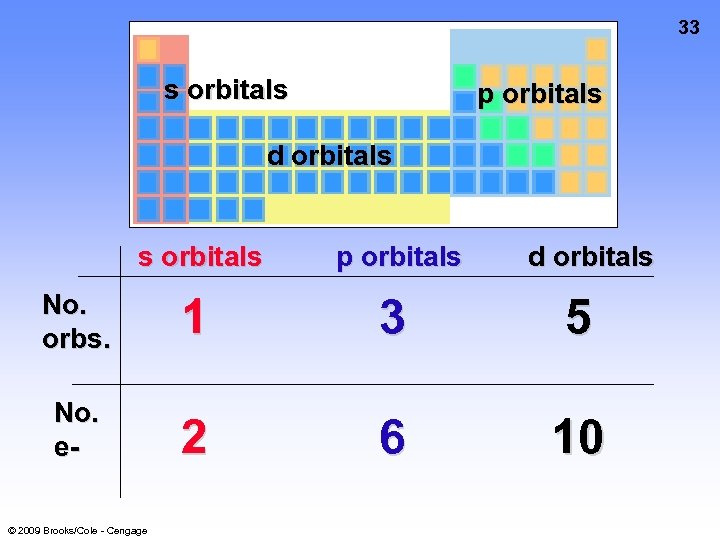

Orbitals 32 • No more than 2 e- assigned to an orbital • Orbitals grouped in s, p, d (and f) subshells s orbitals d orbitals © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage p orbitals

33 s orbitals p orbitals d orbitals s orbitals p orbitals No. orbs. 1 3 5 No. e- 2 6 10 © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage d orbitals

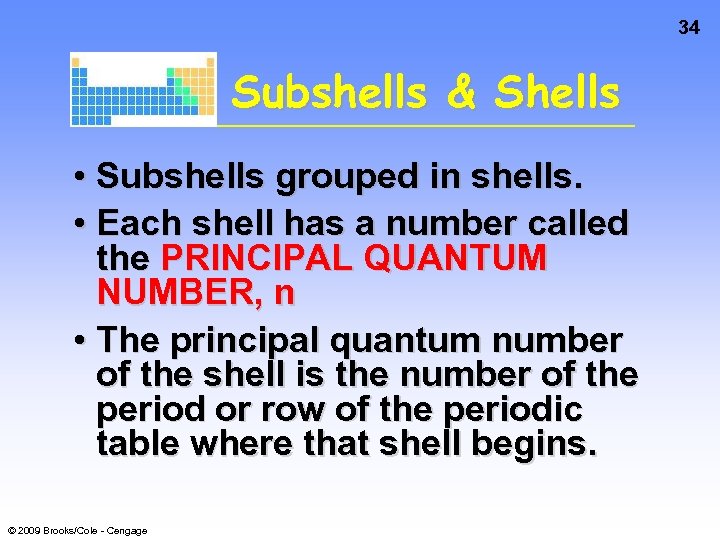

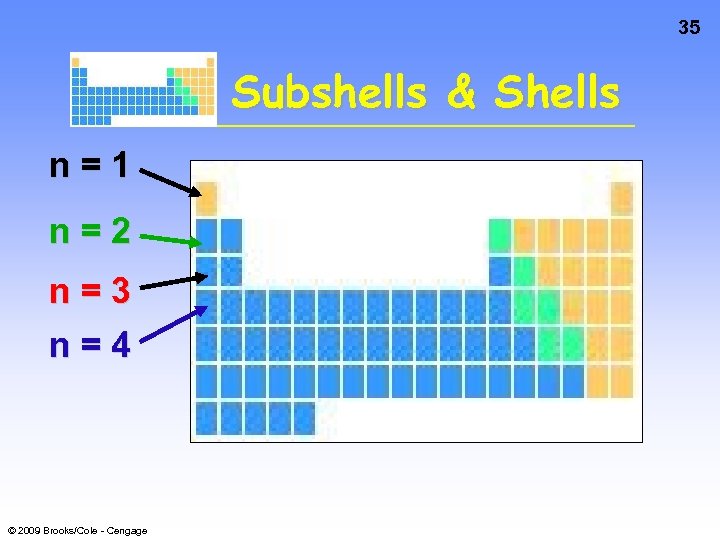

34 Subshells & Shells • Subshells grouped in shells. • Each shell has a number called the PRINCIPAL QUANTUM NUMBER, n • The principal quantum number of the shell is the number of the period or row of the periodic table where that shell begins. © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage

35 Subshells & Shells n=1 n=2 n=3 n=4 © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage

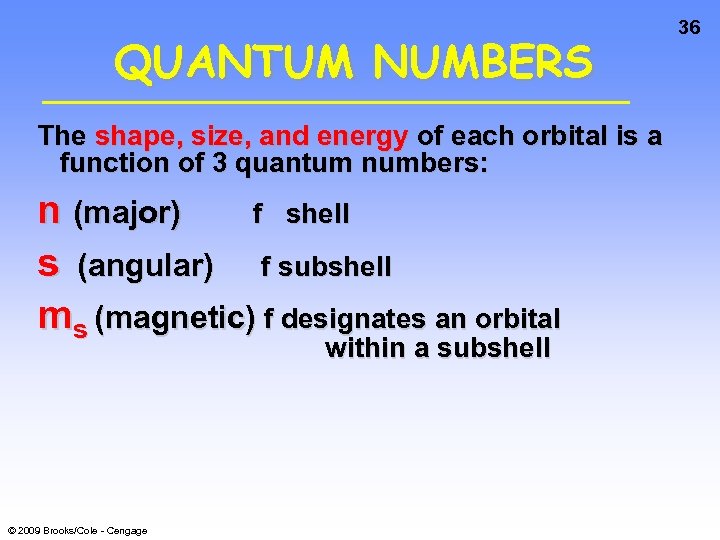

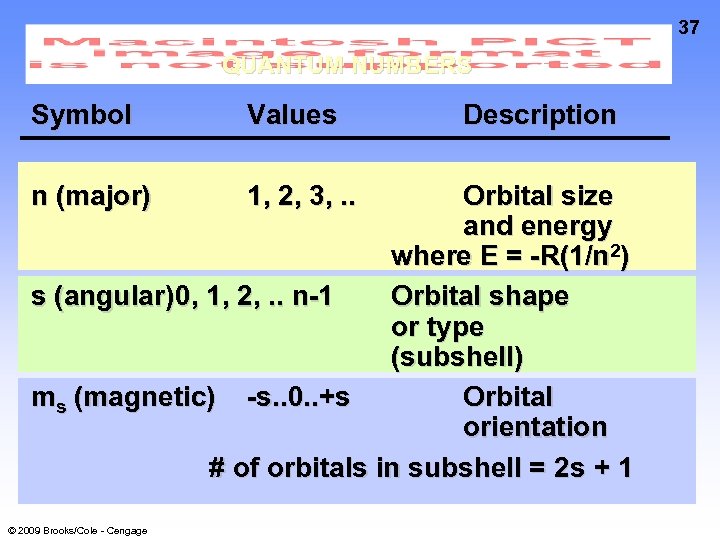

QUANTUM NUMBERS The shape, size, and energy of each orbital is a function of 3 quantum numbers: n (major) f shell s (angular) f subshell ms (magnetic) f designates an orbital within a subshell © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage 36

37 QUANTUM NUMBERS Symbol Values n (major) 1, 2, 3, . . Description Orbital size and energy where E = -R(1/n 2) s (angular) 0, 1, 2, . . n-1 Orbital shape or type (subshell) ms (magnetic) -s. . 0. . +s Orbital orientation # of orbitals in subshell = 2 s + 1 © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage

38 Types of Atomic Orbitals See Active Figure 6. 14 © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage

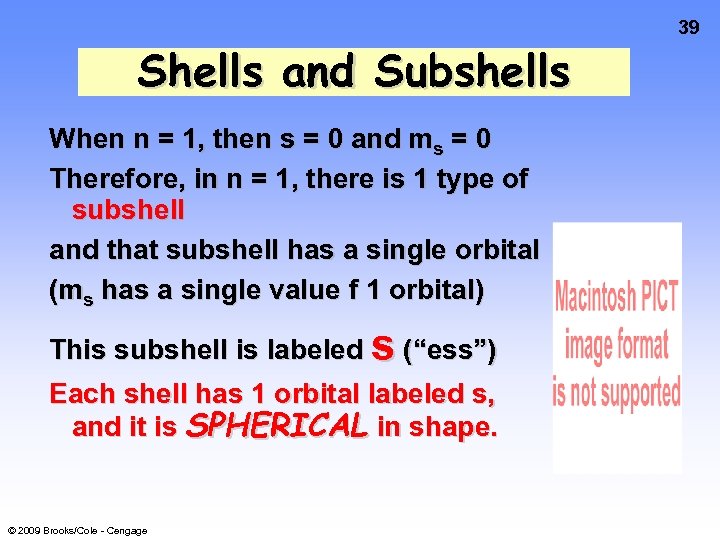

Shells and Subshells When n = 1, then s = 0 and ms = 0 Therefore, in n = 1, there is 1 type of subshell and that subshell has a single orbital (ms has a single value f 1 orbital) This subshell is labeled s (“ess”) Each shell has 1 orbital labeled s, and it is SPHERICAL in shape. © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage 39

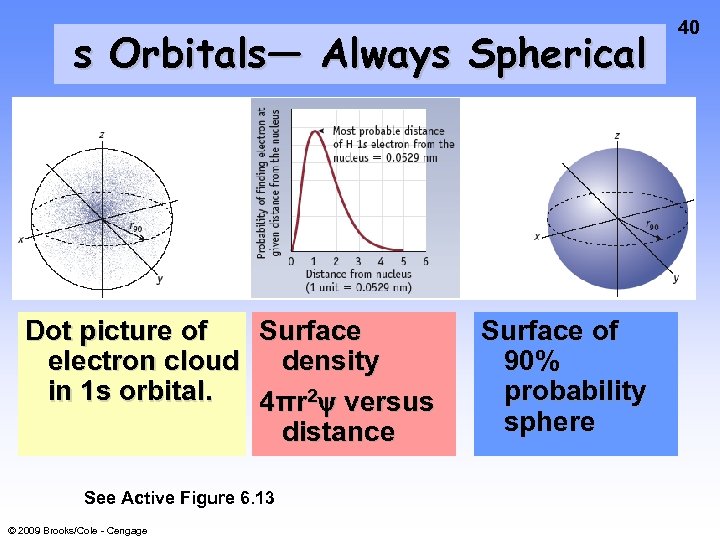

s Orbitals— Always Spherical Dot picture of Surface electron cloud density in 1 s orbital. 4πr 2 y versus distance See Active Figure 6. 13 © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage Surface of 90% probability sphere 40

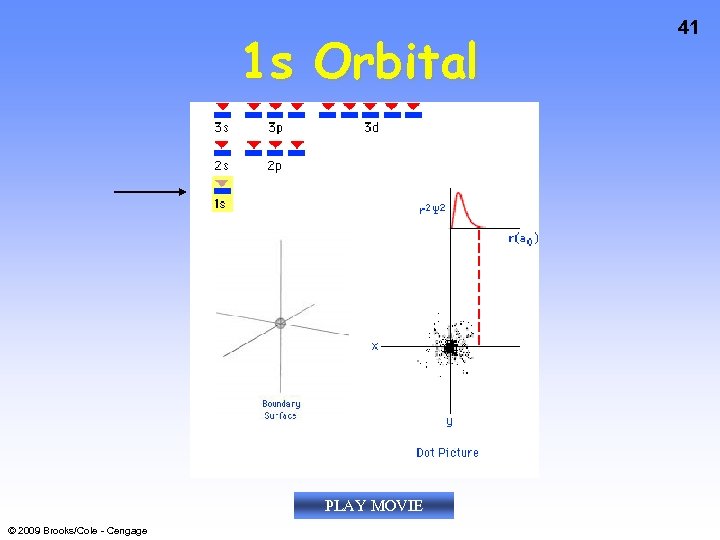

1 s Orbital PLAY MOVIE © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage 41

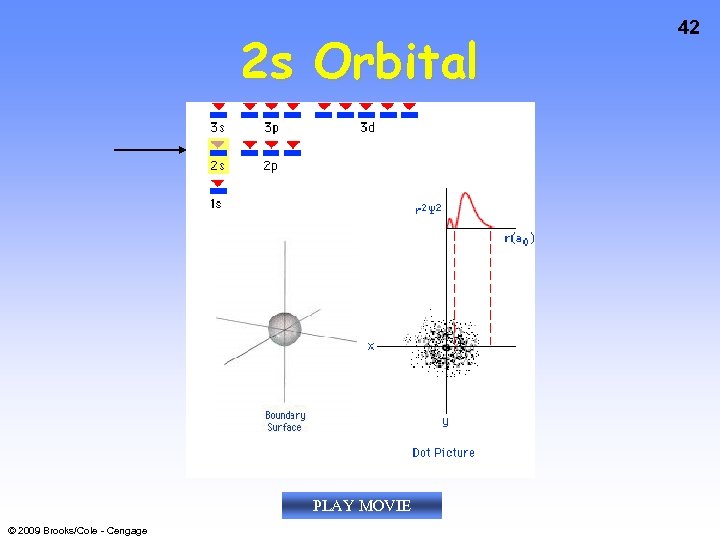

2 s Orbital PLAY MOVIE © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage 42

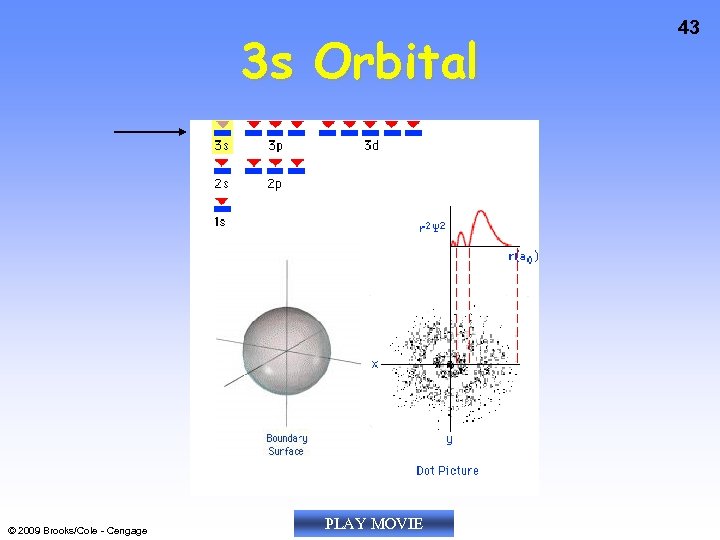

3 s Orbital © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage PLAY MOVIE 43

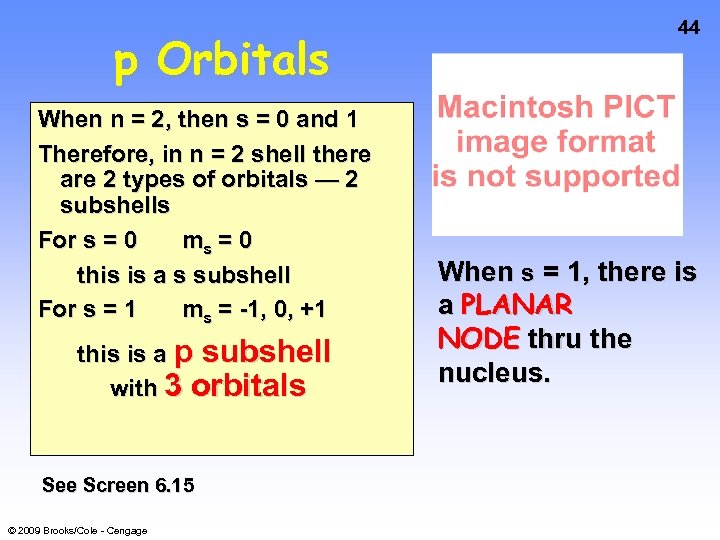

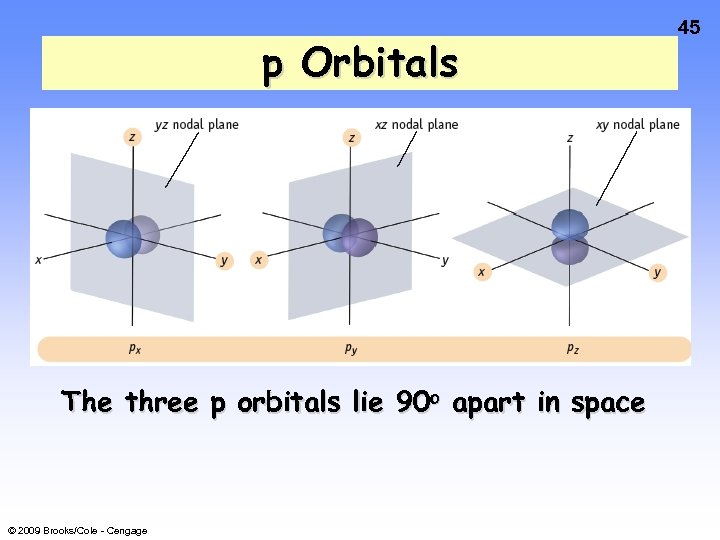

p Orbitals When n = 2, then s = 0 and 1 Therefore, in n = 2 shell there are 2 types of orbitals — 2 subshells For s = 0 ms = 0 this is a s subshell For s = 1 ms = -1, 0, +1 this is a p subshell with 3 orbitals See Screen 6. 15 © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage 44 When s = 1, there is a PLANAR NODE thru the nucleus.

p Orbitals The three p orbitals lie 90 o apart in space © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage 45

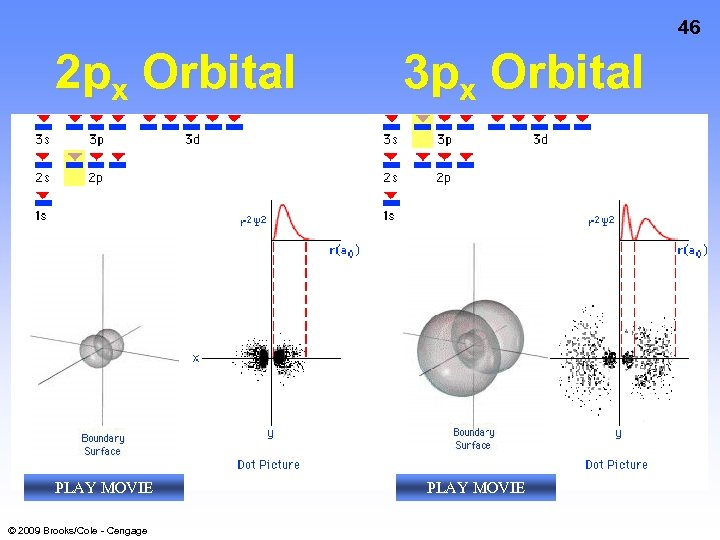

46 2 px Orbital PLAY MOVIE © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage 3 px Orbital PLAY MOVIE

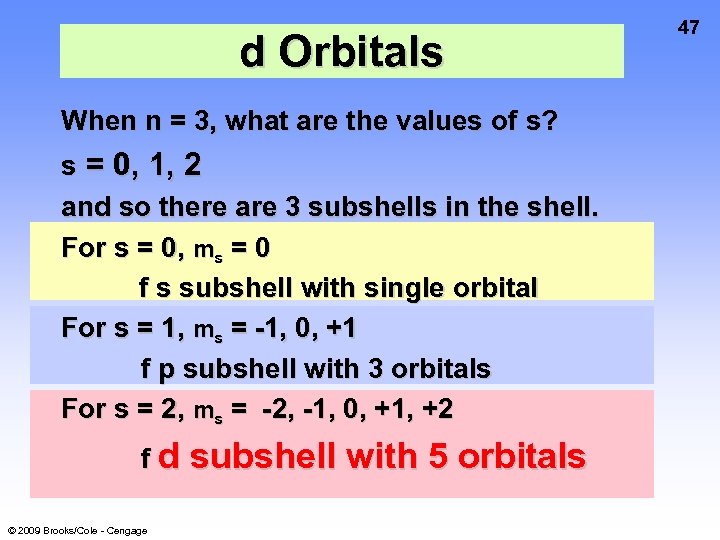

d Orbitals When n = 3, what are the values of s? s = 0, 1, 2 and so there are 3 subshells in the shell. For s = 0, ms = 0 f s subshell with single orbital For s = 1, ms = -1, 0, +1 f p subshell with 3 orbitals For s = 2, ms = -2, -1, 0, +1, +2 fd © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage subshell with 5 orbitals 47

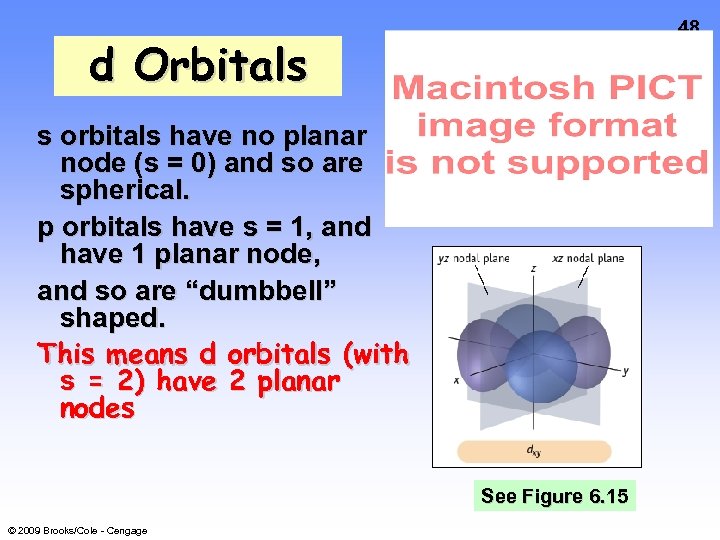

48 d Orbitals s orbitals have no planar node (s = 0) and so are spherical. p orbitals have s = 1, and have 1 planar node, and so are “dumbbell” shaped. This means d orbitals (with s = 2) have 2 planar nodes See Figure 6. 15 © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage

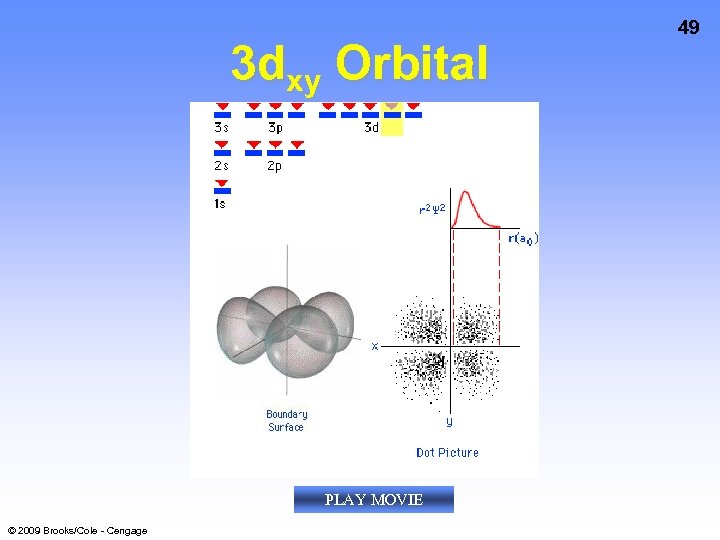

3 dxy Orbital PLAY MOVIE © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage 49

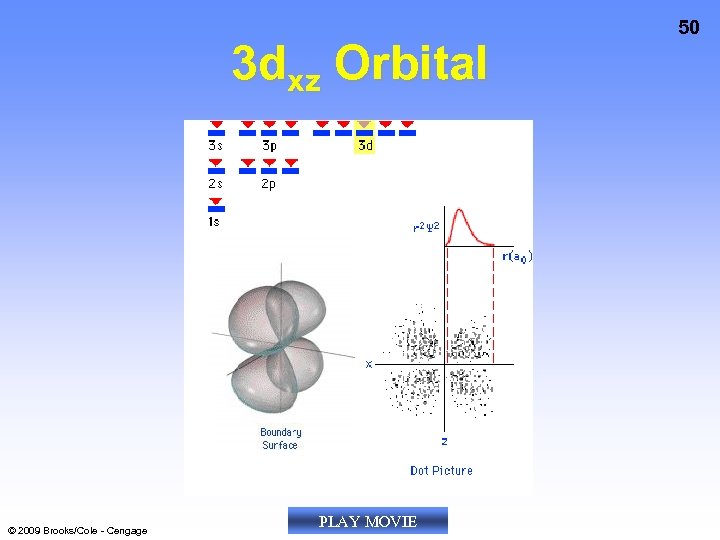

3 dxz Orbital © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage PLAY MOVIE 50

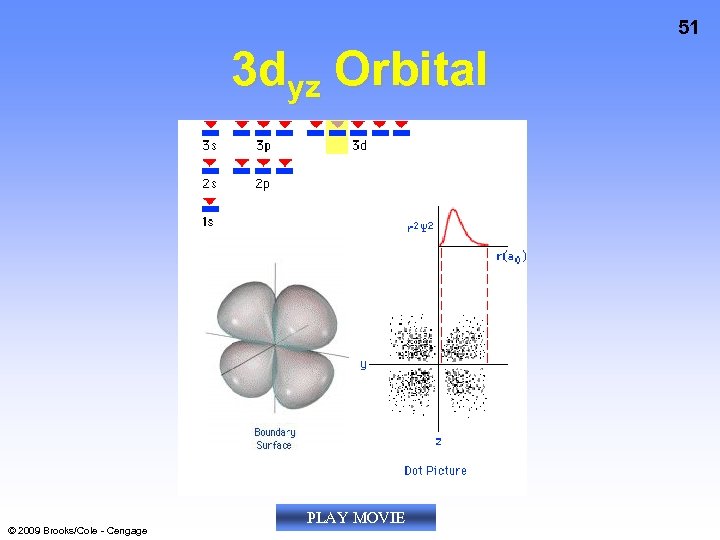

51 3 dyz Orbital © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage PLAY MOVIE

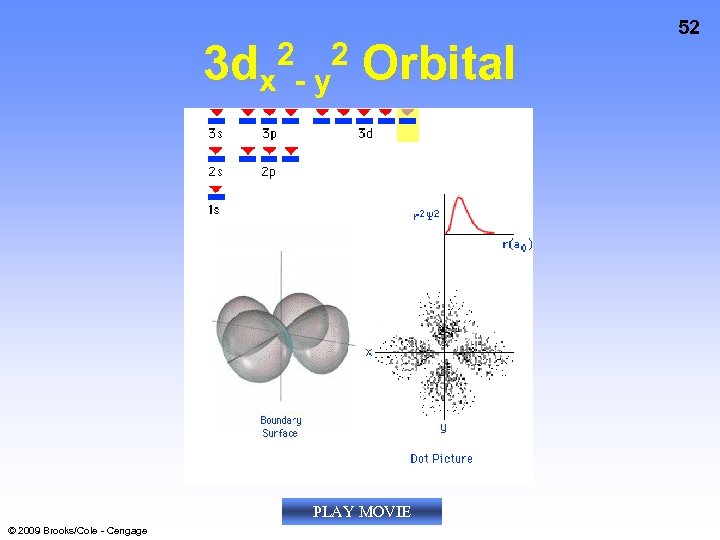

3 dx 2 - y 2 Orbital PLAY MOVIE © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage 52

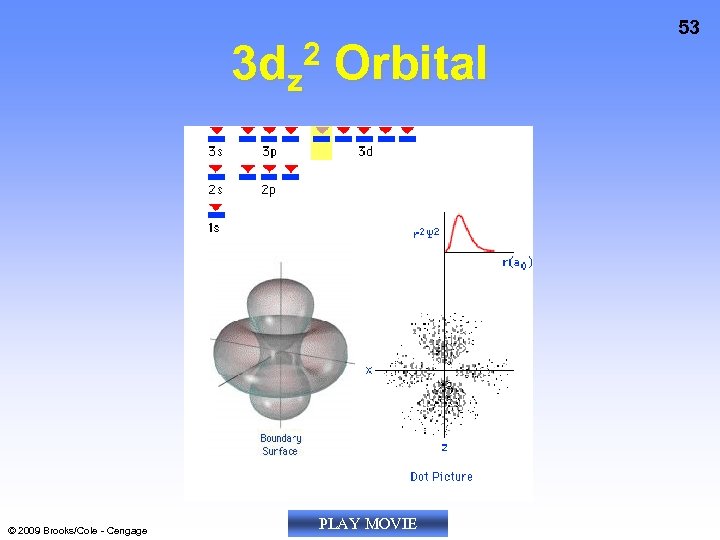

3 dz 2 Orbital © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage PLAY MOVIE 53

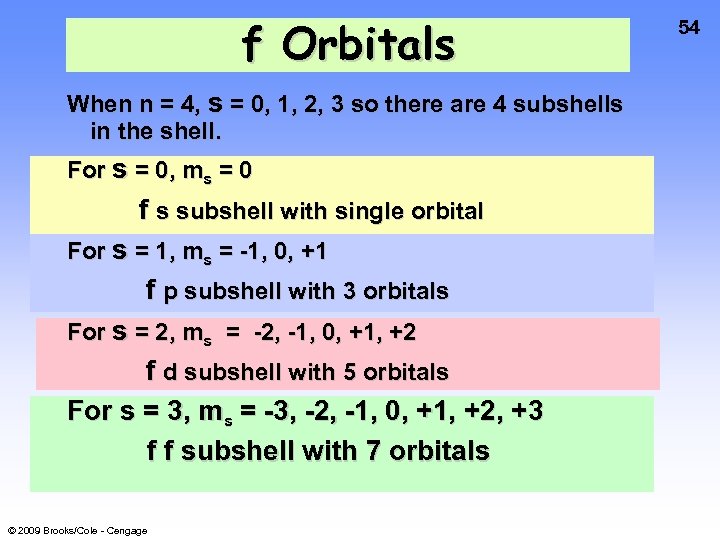

f Orbitals When n = 4, s = 0, 1, 2, 3 so there are 4 subshells in the shell. For s = 0, ms = 0 f s subshell with single orbital For s = 1, ms = -1, 0, +1 f p subshell with 3 orbitals For s = 2, ms = -2, -1, 0, +1, +2 f d subshell with 5 orbitals For s = 3, ms = -3, -2, -1, 0, +1, +2, +3 f f subshell with 7 orbitals © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage 54

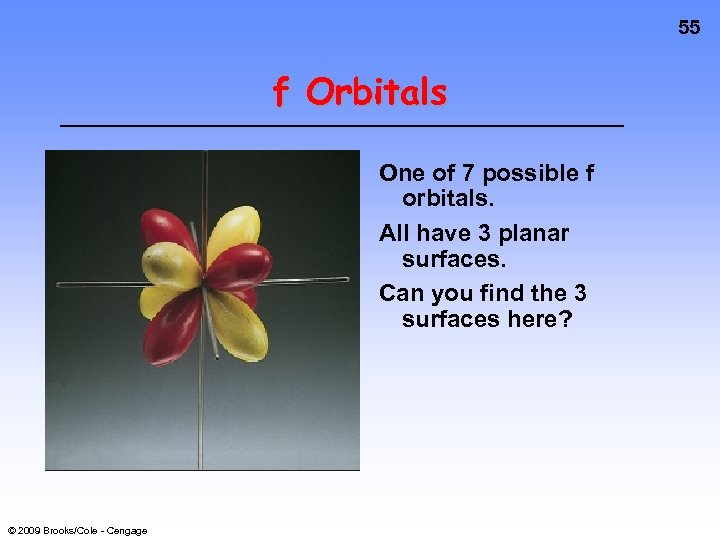

55 f Orbitals One of 7 possible f orbitals. All have 3 planar surfaces. Can you find the 3 surfaces here? © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage

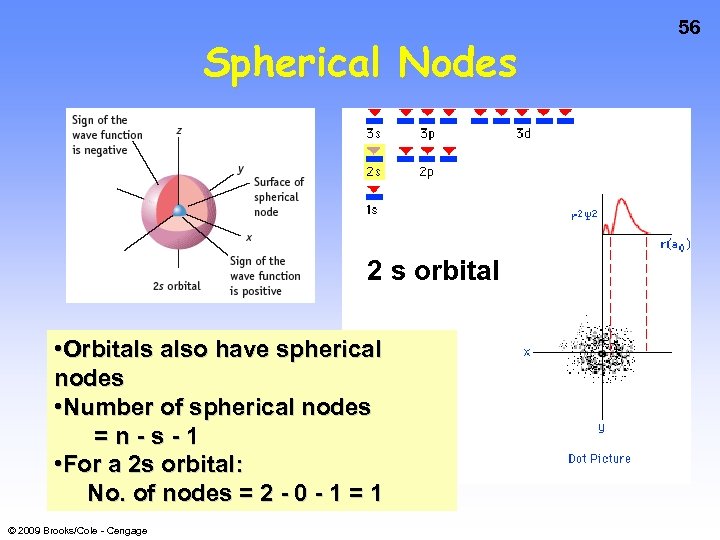

Spherical Nodes 2 s orbital • Orbitals also have spherical nodes • Number of spherical nodes =n-s-1 • For a 2 s orbital: No. of nodes = 2 - 0 - 1 = 1 © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage 56

Arrangement of Electrons in Atoms Electrons in atoms are arranged as SHELLS (n) SUBSHELLS (s) ORBITALS (ms) © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage 57

Arrangement of Electrons in Atoms Each orbital can be assigned no more than 2 electrons! This is tied to the existence of a 4 th quantum number, the electron spin quantum number, ms. © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage 58

59 PLAY MOVIE Electron Spin Quantum Number, ms Can be proved experimentally that electron has an intrinsic property referred to as “spin. ” Two spin directions are given by ms where ms = +1/2 and -1/2. © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage

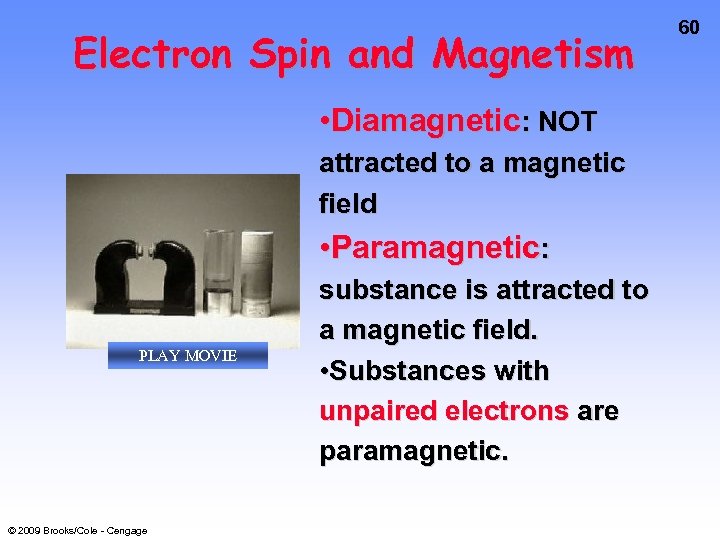

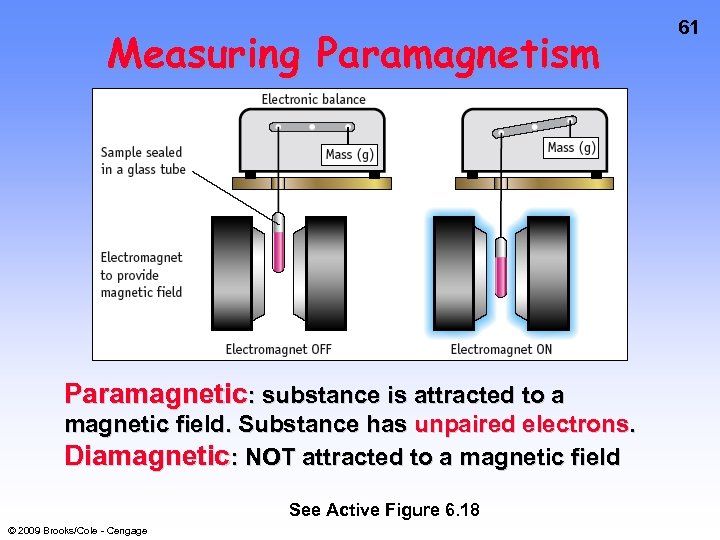

Electron Spin and Magnetism • Diamagnetic: NOT attracted to a magnetic field • Paramagnetic: PLAY MOVIE © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage substance is attracted to a magnetic field. • Substances with unpaired electrons are paramagnetic. 60

Measuring Paramagnetism Paramagnetic: substance is attracted to a magnetic field. Substance has unpaired electrons. Diamagnetic: NOT attracted to a magnetic field See Active Figure 6. 18 © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage 61

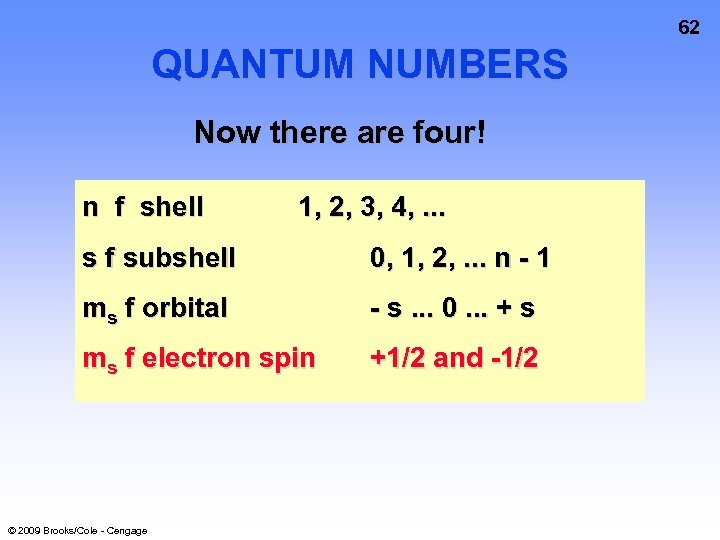

62 QUANTUM NUMBERS Now there are four! n f shell 1, 2, 3, 4, . . . s f subshell 0, 1, 2, . . . n - 1 ms f orbital - s. . . 0. . . + s ms f electron spin +1/2 and -1/2 © 2009 Brooks/Cole - Cengage

c325b5cef2d82ec7646ff2fdca0bc543.ppt