bde08b396aec65c48174eed17882b518.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 29

1 A Dynamic Code Mapping Technique for Scratchpad Memories in Embedded Systems Master’s Thesis Defense October 2008 Amit Pabalkar Compiler and Micro-architecture Lab School of Computing and Informatics Arizona State University

1 A Dynamic Code Mapping Technique for Scratchpad Memories in Embedded Systems Master’s Thesis Defense October 2008 Amit Pabalkar Compiler and Micro-architecture Lab School of Computing and Informatics Arizona State University

2 Agenda • • Motivation SPM Advantage SPM Challenges Previous Approach Code Mapping Technique Results Continuing Effort

2 Agenda • • Motivation SPM Advantage SPM Challenges Previous Approach Code Mapping Technique Results Continuing Effort

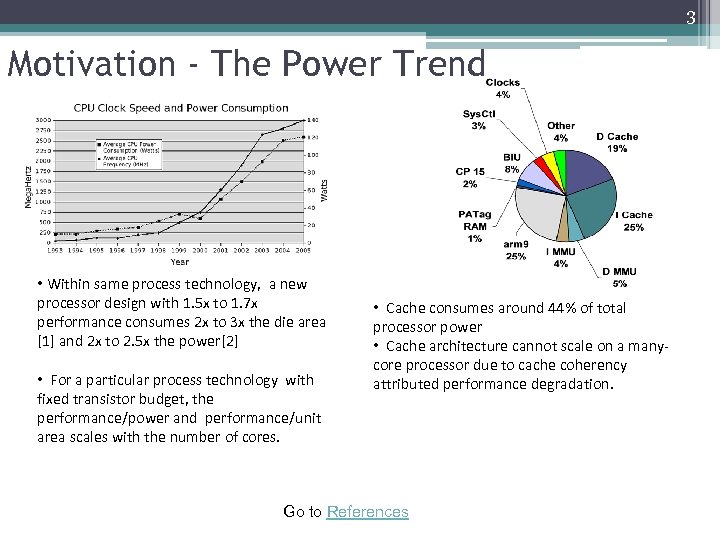

3 Motivation - The Power Trend • Within same process technology, a new processor design with 1. 5 x to 1. 7 x performance consumes 2 x to 3 x the die area [1] and 2 x to 2. 5 x the power[2] • For a particular process technology with fixed transistor budget, the performance/power and performance/unit area scales with the number of cores. • Cache consumes around 44% of total processor power • Cache architecture cannot scale on a manycore processor due to cache coherency attributed performance degradation. Go to References

3 Motivation - The Power Trend • Within same process technology, a new processor design with 1. 5 x to 1. 7 x performance consumes 2 x to 3 x the die area [1] and 2 x to 2. 5 x the power[2] • For a particular process technology with fixed transistor budget, the performance/power and performance/unit area scales with the number of cores. • Cache consumes around 44% of total processor power • Cache architecture cannot scale on a manycore processor due to cache coherency attributed performance degradation. Go to References

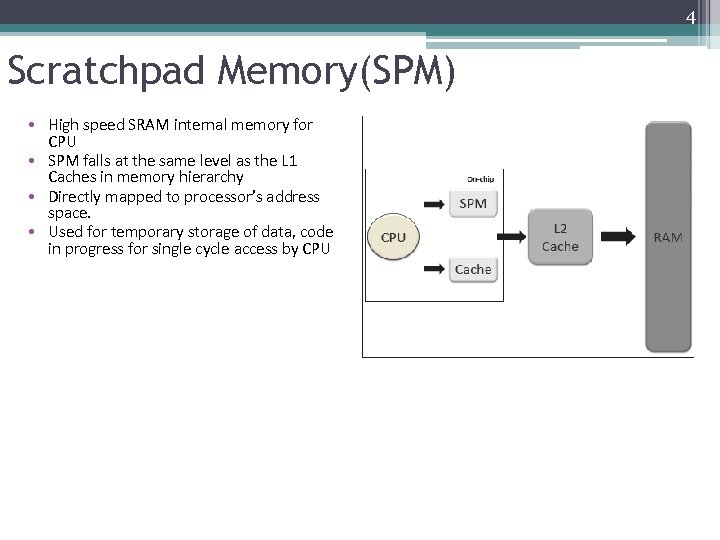

4 Scratchpad Memory(SPM) • High speed SRAM internal memory for CPU • SPM falls at the same level as the L 1 Caches in memory hierarchy • Directly mapped to processor’s address space. • Used for temporary storage of data, code in progress for single cycle access by CPU

4 Scratchpad Memory(SPM) • High speed SRAM internal memory for CPU • SPM falls at the same level as the L 1 Caches in memory hierarchy • Directly mapped to processor’s address space. • Used for temporary storage of data, code in progress for single cycle access by CPU

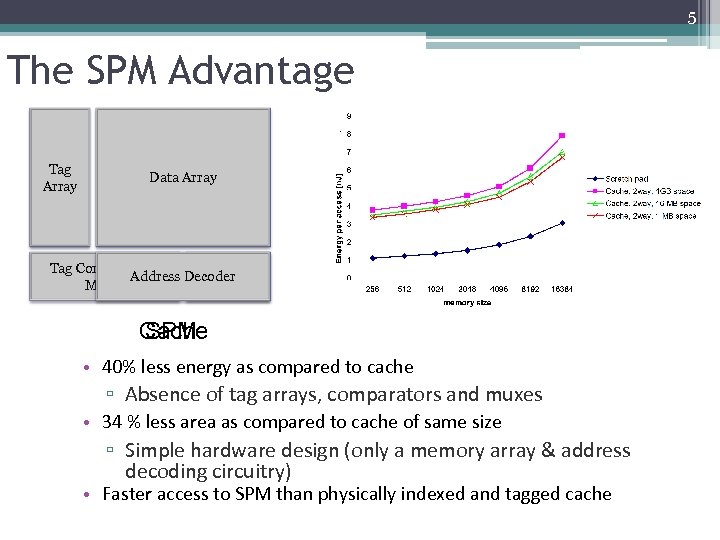

5 The SPM Advantage Tag Array Data Array Tag Comparators, Address Decoder Muxes Decoder Cache SPM • 40% less energy as compared to cache ▫ Absence of tag arrays, comparators and muxes • 34 % less area as compared to cache of same size ▫ Simple hardware design (only a memory array & address decoding circuitry) • Faster access to SPM than physically indexed and tagged cache

5 The SPM Advantage Tag Array Data Array Tag Comparators, Address Decoder Muxes Decoder Cache SPM • 40% less energy as compared to cache ▫ Absence of tag arrays, comparators and muxes • 34 % less area as compared to cache of same size ▫ Simple hardware design (only a memory array & address decoding circuitry) • Faster access to SPM than physically indexed and tagged cache

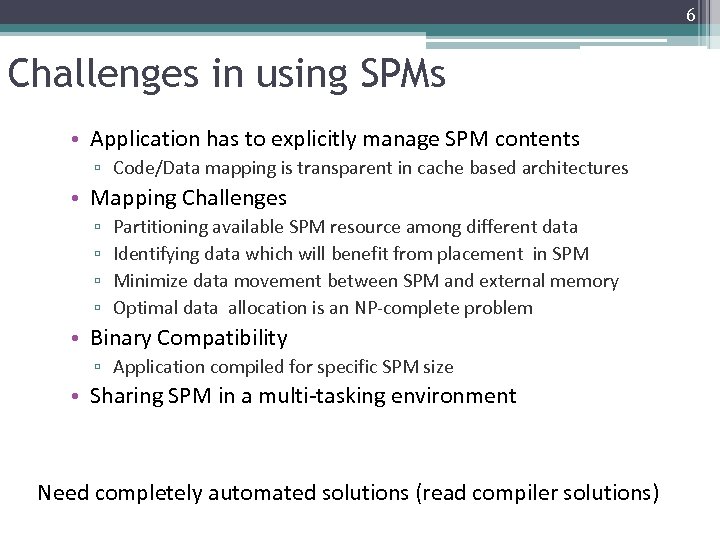

6 Challenges in using SPMs • Application has to explicitly manage SPM contents ▫ Code/Data mapping is transparent in cache based architectures • Mapping Challenges ▫ ▫ Partitioning available SPM resource among different data Identifying data which will benefit from placement in SPM Minimize data movement between SPM and external memory Optimal data allocation is an NP-complete problem • Binary Compatibility ▫ Application compiled for specific SPM size • Sharing SPM in a multi-tasking environment Need completely automated solutions (read compiler solutions)

6 Challenges in using SPMs • Application has to explicitly manage SPM contents ▫ Code/Data mapping is transparent in cache based architectures • Mapping Challenges ▫ ▫ Partitioning available SPM resource among different data Identifying data which will benefit from placement in SPM Minimize data movement between SPM and external memory Optimal data allocation is an NP-complete problem • Binary Compatibility ▫ Application compiled for specific SPM size • Sharing SPM in a multi-tasking environment Need completely automated solutions (read compiler solutions)

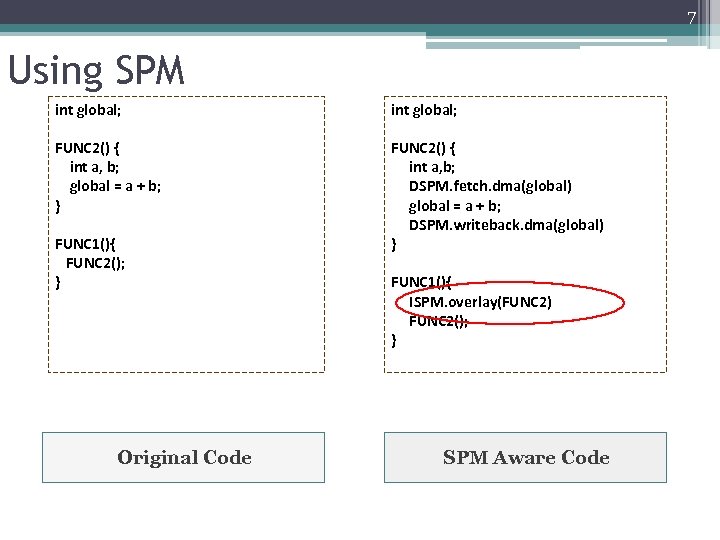

7 Using SPM int global; FUNC 2() { int a, b; global = a + b; } FUNC 2() { int a, b; DSPM. fetch. dma(global) global = a + b; DSPM. writeback. dma(global) } FUNC 1(){ FUNC 2(); } Original Code FUNC 1(){ ISPM. overlay(FUNC 2) FUNC 2(); } SPM Aware Code

7 Using SPM int global; FUNC 2() { int a, b; global = a + b; } FUNC 2() { int a, b; DSPM. fetch. dma(global) global = a + b; DSPM. writeback. dma(global) } FUNC 1(){ FUNC 2(); } Original Code FUNC 1(){ ISPM. overlay(FUNC 2) FUNC 2(); } SPM Aware Code

![8 Previous Work • Static Techniques [3, 4]. Contents of SPM do not change 8 Previous Work • Static Techniques [3, 4]. Contents of SPM do not change](https://present5.com/presentation/bde08b396aec65c48174eed17882b518/image-8.jpg) 8 Previous Work • Static Techniques [3, 4]. Contents of SPM do not change during program execution – less scope for energy reduction. • Profiling is widely used but has some drawbacks [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8] ▫ Profile may depend heavily depend on input data set ▫ Profiling an application as a pre-processing step may be infeasible for many large applications ▫ It can be time consuming, complicated task • ILP solutions do not scale well with problem size [3, 5, 6, 8] • Some techniques demand architectural changes in the system [6, 10] Go to References

8 Previous Work • Static Techniques [3, 4]. Contents of SPM do not change during program execution – less scope for energy reduction. • Profiling is widely used but has some drawbacks [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8] ▫ Profile may depend heavily depend on input data set ▫ Profiling an application as a pre-processing step may be infeasible for many large applications ▫ It can be time consuming, complicated task • ILP solutions do not scale well with problem size [3, 5, 6, 8] • Some techniques demand architectural changes in the system [6, 10] Go to References

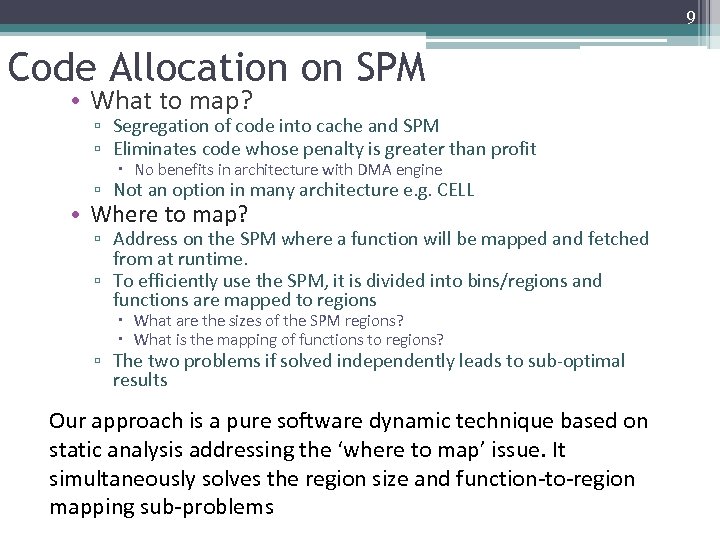

9 Code Allocation on SPM • What to map? ▫ Segregation of code into cache and SPM ▫ Eliminates code whose penalty is greater than profit No benefits in architecture with DMA engine ▫ Not an option in many architecture e. g. CELL • Where to map? ▫ Address on the SPM where a function will be mapped and fetched from at runtime. ▫ To efficiently use the SPM, it is divided into bins/regions and functions are mapped to regions What are the sizes of the SPM regions? What is the mapping of functions to regions? ▫ The two problems if solved independently leads to sub-optimal results Our approach is a pure software dynamic technique based on static analysis addressing the ‘where to map’ issue. It simultaneously solves the region size and function-to-region mapping sub-problems

9 Code Allocation on SPM • What to map? ▫ Segregation of code into cache and SPM ▫ Eliminates code whose penalty is greater than profit No benefits in architecture with DMA engine ▫ Not an option in many architecture e. g. CELL • Where to map? ▫ Address on the SPM where a function will be mapped and fetched from at runtime. ▫ To efficiently use the SPM, it is divided into bins/regions and functions are mapped to regions What are the sizes of the SPM regions? What is the mapping of functions to regions? ▫ The two problems if solved independently leads to sub-optimal results Our approach is a pure software dynamic technique based on static analysis addressing the ‘where to map’ issue. It simultaneously solves the region size and function-to-region mapping sub-problems

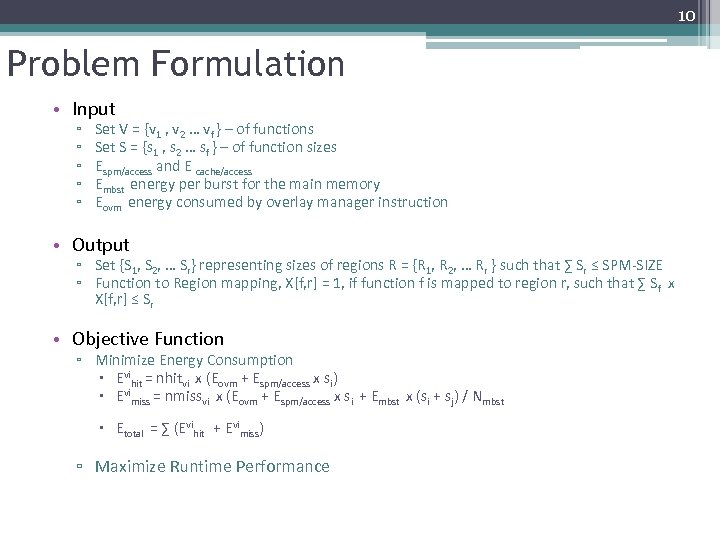

10 Problem Formulation • Input ▫ ▫ ▫ Set V = {v 1 , v 2 … vf } – of functions Set S = {s 1 , s 2 … sf } – of function sizes Espm/access and E cache/access Embst energy per burst for the main memory Eovm energy consumed by overlay manager instruction • Output ▫ Set {S 1, S 2, … Sr} representing sizes of regions R = {R 1, R 2, … Rr } such that ∑ Sr ≤ SPM-SIZE ▫ Function to Region mapping, X[f, r] = 1, if function f is mapped to region r, such that ∑ S f x X[f, r] ≤ Sr • Objective Function ▫ Minimize Energy Consumption Evihit = nhitvi x (Eovm + Espm/access x si) Evimiss = nmissvi x (Eovm + Espm/access x si + Embst x (si + sj) / Nmbst Etotal = ∑ (Evihit + Evimiss) ▫ Maximize Runtime Performance

10 Problem Formulation • Input ▫ ▫ ▫ Set V = {v 1 , v 2 … vf } – of functions Set S = {s 1 , s 2 … sf } – of function sizes Espm/access and E cache/access Embst energy per burst for the main memory Eovm energy consumed by overlay manager instruction • Output ▫ Set {S 1, S 2, … Sr} representing sizes of regions R = {R 1, R 2, … Rr } such that ∑ Sr ≤ SPM-SIZE ▫ Function to Region mapping, X[f, r] = 1, if function f is mapped to region r, such that ∑ S f x X[f, r] ≤ Sr • Objective Function ▫ Minimize Energy Consumption Evihit = nhitvi x (Eovm + Espm/access x si) Evimiss = nmissvi x (Eovm + Espm/access x si + Embst x (si + sj) / Nmbst Etotal = ∑ (Evihit + Evimiss) ▫ Maximize Runtime Performance

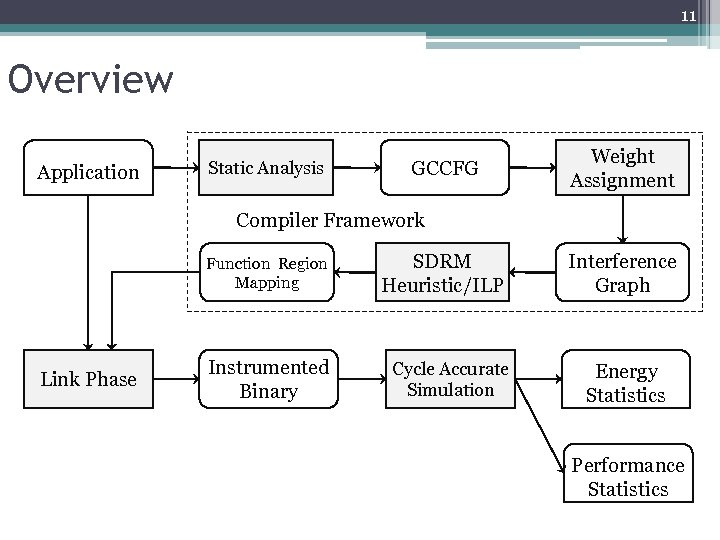

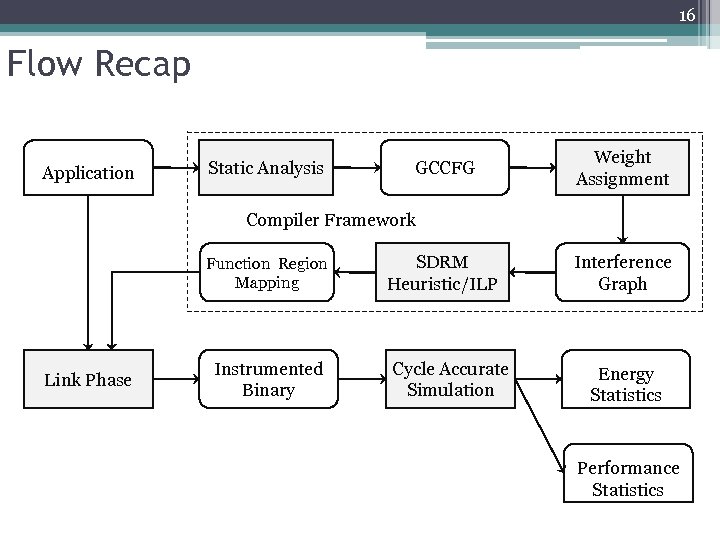

11 Overview Application Static Analysis GCCFG Weight Assignment Compiler Framework Function Region Mapping Link Phase Instrumented Binary SDRM Heuristic/ILP Cycle Accurate Simulation Interference Graph Energy Statistics Performance Statistics

11 Overview Application Static Analysis GCCFG Weight Assignment Compiler Framework Function Region Mapping Link Phase Instrumented Binary SDRM Heuristic/ILP Cycle Accurate Simulation Interference Graph Energy Statistics Performance Statistics

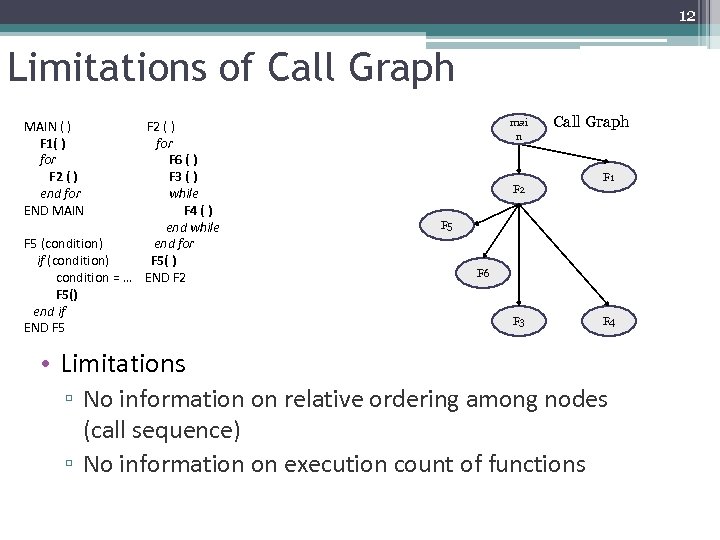

12 Limitations of Call Graph F 2 ( ) for F 6 ( ) F 3 ( ) while F 4 ( ) end while F 5 (condition) end for if (condition) F 5( ) condition = … END F 2 F 5() end if END F 5 mai n MAIN ( ) F 1( ) for F 2 ( ) end for END MAIN F 2 Call Graph F 1 F 5 F 6 F 3 F 4 • Limitations ▫ No information on relative ordering among nodes (call sequence) ▫ No information on execution count of functions

12 Limitations of Call Graph F 2 ( ) for F 6 ( ) F 3 ( ) while F 4 ( ) end while F 5 (condition) end for if (condition) F 5( ) condition = … END F 2 F 5() end if END F 5 mai n MAIN ( ) F 1( ) for F 2 ( ) end for END MAIN F 2 Call Graph F 1 F 5 F 6 F 3 F 4 • Limitations ▫ No information on relative ordering among nodes (call sequence) ▫ No information on execution count of functions

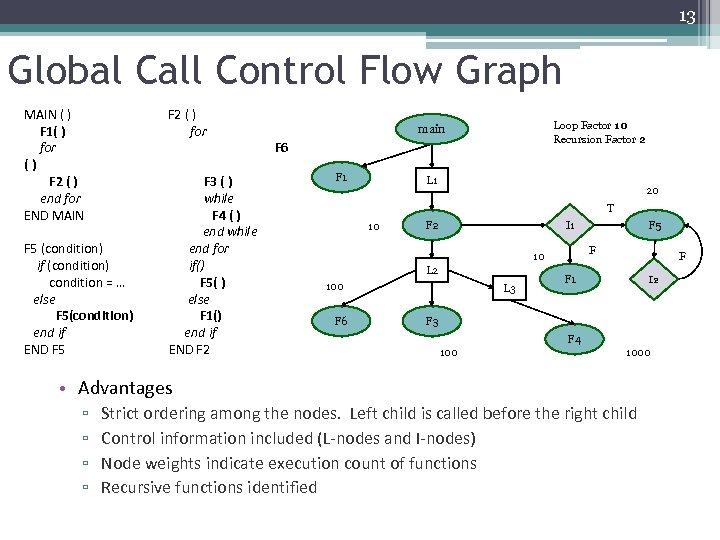

13 Global Call Control Flow Graph MAIN ( ) F 1( ) for () F 2 ( ) end for END MAIN F 2 ( ) for F 5 (condition) if (condition) condition = … else F 5(condition) end if END F 5 F 3 ( ) while F 4 ( ) end while end for if() F 5( ) else F 1() end if END F 2 Loop Factor 10 Recursion Factor 2 main F 6 F 1 L 1 20 T 10 F 2 F 10 L 2 100 F 6 F 5 I 1 L 3 F F 1 I 2 F 3 F 4 1000 • Advantages ▫ ▫ Strict ordering among the nodes. Left child is called before the right child Control information included (L-nodes and I-nodes) Node weights indicate execution count of functions Recursive functions identified

13 Global Call Control Flow Graph MAIN ( ) F 1( ) for () F 2 ( ) end for END MAIN F 2 ( ) for F 5 (condition) if (condition) condition = … else F 5(condition) end if END F 5 F 3 ( ) while F 4 ( ) end while end for if() F 5( ) else F 1() end if END F 2 Loop Factor 10 Recursion Factor 2 main F 6 F 1 L 1 20 T 10 F 2 F 10 L 2 100 F 6 F 5 I 1 L 3 F F 1 I 2 F 3 F 4 1000 • Advantages ▫ ▫ Strict ordering among the nodes. Left child is called before the right child Control information included (L-nodes and I-nodes) Node weights indicate execution count of functions Recursive functions identified

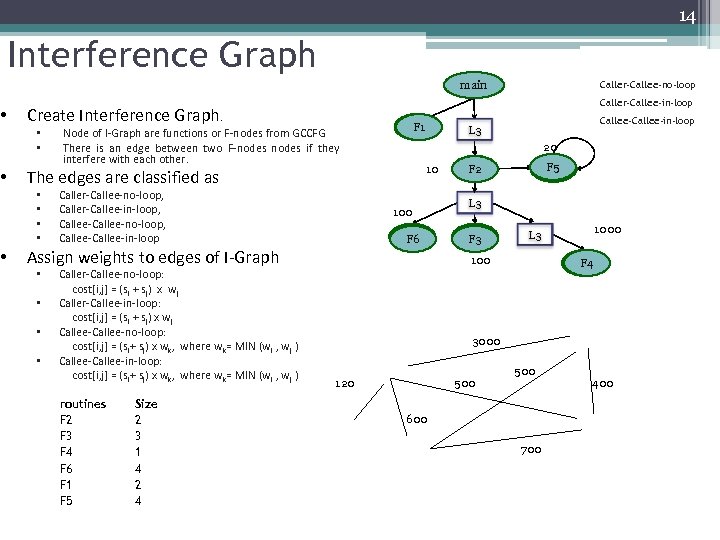

• • • 14 Interference Graph Caller-Callee-no-loop main Caller-Callee-in-loop Create Interference Graph. • • Node of I-Graph are functions or F-nodes from GCCFG There is an edge between two F-nodes if they interfere with each other. F 1 20 10 The edges are classified as • • Caller-Callee-no-loop, Caller-Callee-in-loop, Callee-no-loop, Callee-in-loop 100 F 6 Assign weights to edges of I-Graph • • Caller-Callee-no-loop: cost[i, j] = (si + sj) x wj Caller-Callee-in-loop: cost[i, j] = (si + sj) x wj Callee-no-loop: cost[i, j] = (si+ sj) x wk, where wk= MIN (wi , wj ) Callee-in-loop: cost[i, j] = (si+ sj) x wk, where wk= MIN (wi , wj ) routines F 2 F 3 F 4 F 6 F 1 F 5 Size 2 3 1 4 2 4 Callee-in-loop L 3 F 5 F 2 L 3 F 3 1000 L 3 100 F 4 3000 120 500 600 700 400

• • • 14 Interference Graph Caller-Callee-no-loop main Caller-Callee-in-loop Create Interference Graph. • • Node of I-Graph are functions or F-nodes from GCCFG There is an edge between two F-nodes if they interfere with each other. F 1 20 10 The edges are classified as • • Caller-Callee-no-loop, Caller-Callee-in-loop, Callee-no-loop, Callee-in-loop 100 F 6 Assign weights to edges of I-Graph • • Caller-Callee-no-loop: cost[i, j] = (si + sj) x wj Caller-Callee-in-loop: cost[i, j] = (si + sj) x wj Callee-no-loop: cost[i, j] = (si+ sj) x wk, where wk= MIN (wi , wj ) Callee-in-loop: cost[i, j] = (si+ sj) x wk, where wk= MIN (wi , wj ) routines F 2 F 3 F 4 F 6 F 1 F 5 Size 2 3 1 4 2 4 Callee-in-loop L 3 F 5 F 2 L 3 F 3 1000 L 3 100 F 4 3000 120 500 600 700 400

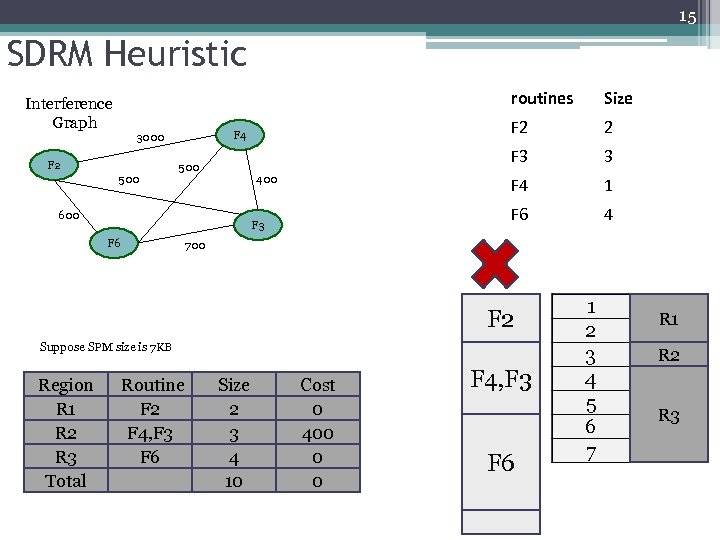

15 SDRM Heuristic routines Interference Graph F 2 500 600 F 6 4 700 Suppose SPM size is 7 KB Region R 1 R 2 R 3 Total 1 F 6 F 3 3 F 4 400 2 F 3 F 4 3000 Size Routine F 2 F 4, F 3 F 4 F 6, F 3 F 6 Size 2 3 1 4 10 9 3 7 Cost 0 400 0 700 0 F 2 F 4, F 3 F 6, F 3 F 6 F 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 R 1 R 2 R 3

15 SDRM Heuristic routines Interference Graph F 2 500 600 F 6 4 700 Suppose SPM size is 7 KB Region R 1 R 2 R 3 Total 1 F 6 F 3 3 F 4 400 2 F 3 F 4 3000 Size Routine F 2 F 4, F 3 F 4 F 6, F 3 F 6 Size 2 3 1 4 10 9 3 7 Cost 0 400 0 700 0 F 2 F 4, F 3 F 6, F 3 F 6 F 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 R 1 R 2 R 3

16 Flow Recap Application Static Analysis GCCFG Weight Assignment Compiler Framework Function Region Mapping Link Phase Instrumented Binary SDRM Heuristic/ILP Cycle Accurate Simulation Interference Graph Energy Statistics Performance Statistics

16 Flow Recap Application Static Analysis GCCFG Weight Assignment Compiler Framework Function Region Mapping Link Phase Instrumented Binary SDRM Heuristic/ILP Cycle Accurate Simulation Interference Graph Energy Statistics Performance Statistics

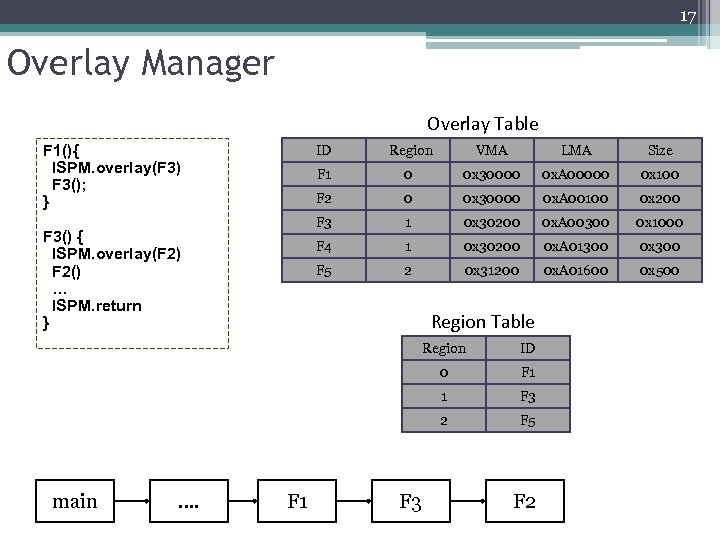

17 Overlay Manager Overlay Table F 1(){ ISPM. overlay(F 3) F 3(); } ID VMA LMA Size F 1 0 0 x 30000 0 x. A 00000 0 x 100 F 2 0 0 x 30000 0 x. A 00100 0 x 200 F 3 1 0 x 30200 0 x. A 00300 0 x 1000 F 4 1 0 x 30200 0 x. A 01300 0 x 300 F 5 F 3() { ISPM. overlay(F 2) F 2() … ISPM. return } Region 2 0 x 31200 0 x. A 01600 0 x 500 Region Table Region 0 F 1 F 3 2 …. F 2 F 1 1 main ID F 5 F 3 F 2

17 Overlay Manager Overlay Table F 1(){ ISPM. overlay(F 3) F 3(); } ID VMA LMA Size F 1 0 0 x 30000 0 x. A 00000 0 x 100 F 2 0 0 x 30000 0 x. A 00100 0 x 200 F 3 1 0 x 30200 0 x. A 00300 0 x 1000 F 4 1 0 x 30200 0 x. A 01300 0 x 300 F 5 F 3() { ISPM. overlay(F 2) F 2() … ISPM. return } Region 2 0 x 31200 0 x. A 01600 0 x 500 Region Table Region 0 F 1 F 3 2 …. F 2 F 1 1 main ID F 5 F 3 F 2

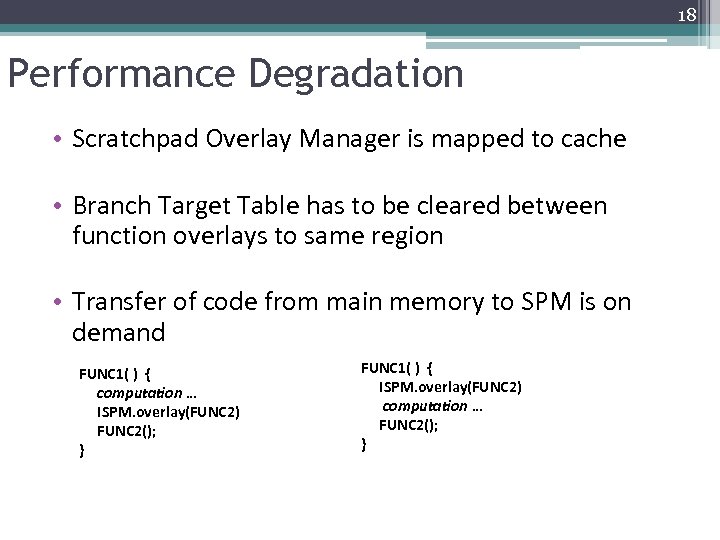

18 Performance Degradation • Scratchpad Overlay Manager is mapped to cache • Branch Target Table has to be cleared between function overlays to same region • Transfer of code from main memory to SPM is on demand FUNC 1( ) { computation … ISPM. overlay(FUNC 2) FUNC 2(); } FUNC 1( ) { ISPM. overlay(FUNC 2) computation … FUNC 2(); }

18 Performance Degradation • Scratchpad Overlay Manager is mapped to cache • Branch Target Table has to be cleared between function overlays to same region • Transfer of code from main memory to SPM is on demand FUNC 1( ) { computation … ISPM. overlay(FUNC 2) FUNC 2(); } FUNC 1( ) { ISPM. overlay(FUNC 2) computation … FUNC 2(); }

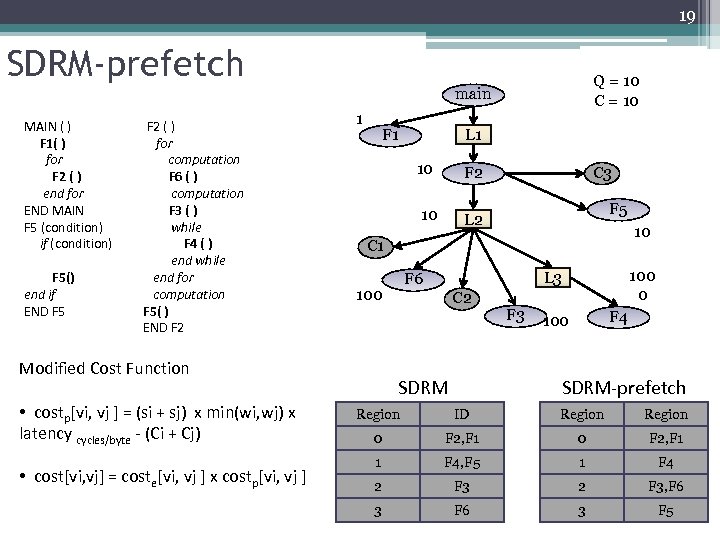

19 SDRM-prefetch Q = 10 C = 10 main MAIN ( ) F 1( ) for F 2 ( ) end for END MAIN F 5 (condition) if (condition) F 5() end if END F 5 F 2 ( ) for computation F 6 ( ) computation F 3 ( ) while F 4 ( ) end while end for computation F 5( ) END F 2 1 F 1 10 • cost[vi, vj] = coste[vi, vj ] x costp[vi, vj ] F 2 10 L 2 C 3 F 5 10 C 1 100 0 L 3 F 6 100 Modified Cost Function • costp[vi, vj ] = (si + sj) x min(wi, wj) x latency cycles/byte - (Ci + Cj) L 1 C 2 SDRM F 3 F 4 100 SDRM-prefetch Region ID Region 0 F 2, F 1 F 2 F 1 1 F 4, F 5 1 F 4 2 F 3, F 6 3 F 5

19 SDRM-prefetch Q = 10 C = 10 main MAIN ( ) F 1( ) for F 2 ( ) end for END MAIN F 5 (condition) if (condition) F 5() end if END F 5 F 2 ( ) for computation F 6 ( ) computation F 3 ( ) while F 4 ( ) end while end for computation F 5( ) END F 2 1 F 1 10 • cost[vi, vj] = coste[vi, vj ] x costp[vi, vj ] F 2 10 L 2 C 3 F 5 10 C 1 100 0 L 3 F 6 100 Modified Cost Function • costp[vi, vj ] = (si + sj) x min(wi, wj) x latency cycles/byte - (Ci + Cj) L 1 C 2 SDRM F 3 F 4 100 SDRM-prefetch Region ID Region 0 F 2, F 1 F 2 F 1 1 F 4, F 5 1 F 4 2 F 3, F 6 3 F 5

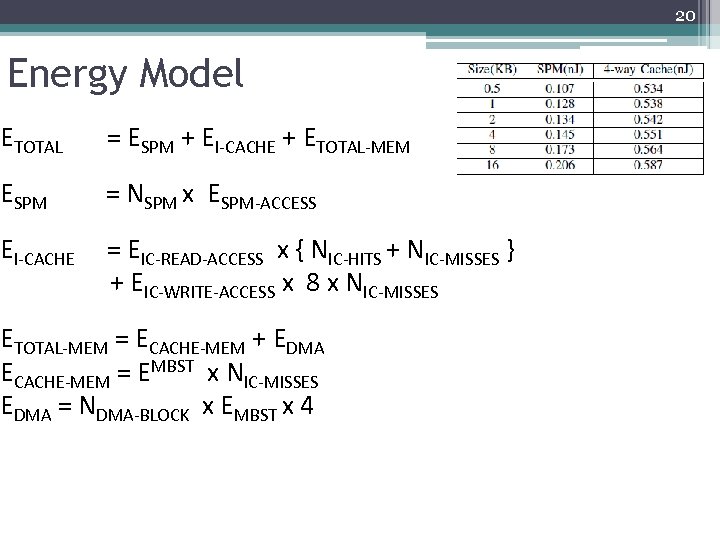

20 Energy Model ETOTAL = ESPM + EI-CACHE + ETOTAL-MEM ESPM = NSPM x ESPM-ACCESS EI-CACHE = EIC-READ-ACCESS x { NIC-HITS + NIC-MISSES } + EIC-WRITE-ACCESS x 8 x NIC-MISSES ETOTAL-MEM = ECACHE-MEM + EDMA ECACHE-MEM = EMBST x NIC-MISSES EDMA = NDMA-BLOCK x EMBST x 4

20 Energy Model ETOTAL = ESPM + EI-CACHE + ETOTAL-MEM ESPM = NSPM x ESPM-ACCESS EI-CACHE = EIC-READ-ACCESS x { NIC-HITS + NIC-MISSES } + EIC-WRITE-ACCESS x 8 x NIC-MISSES ETOTAL-MEM = ECACHE-MEM + EDMA ECACHE-MEM = EMBST x NIC-MISSES EDMA = NDMA-BLOCK x EMBST x 4

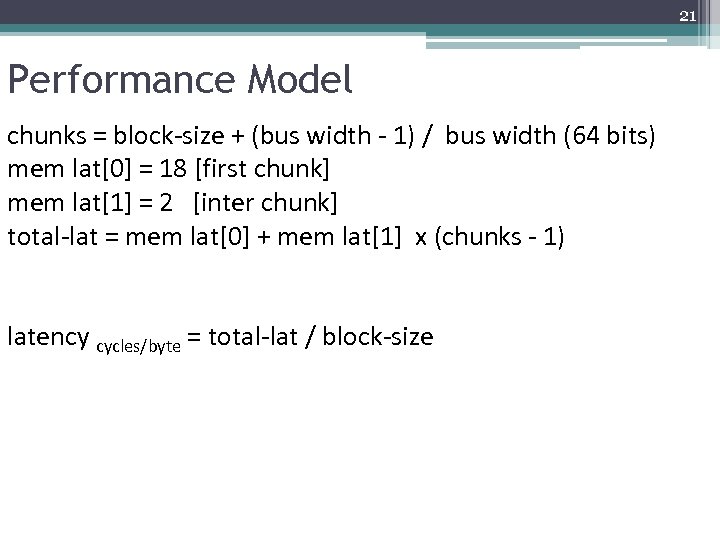

21 Performance Model chunks = block-size + (bus width - 1) / bus width (64 bits) mem lat[0] = 18 [first chunk] mem lat[1] = 2 [inter chunk] total-lat = mem lat[0] + mem lat[1] x (chunks - 1) latency cycles/byte = total-lat / block-size

21 Performance Model chunks = block-size + (bus width - 1) / bus width (64 bits) mem lat[0] = 18 [first chunk] mem lat[1] = 2 [inter chunk] total-lat = mem lat[0] + mem lat[1] x (chunks - 1) latency cycles/byte = total-lat / block-size

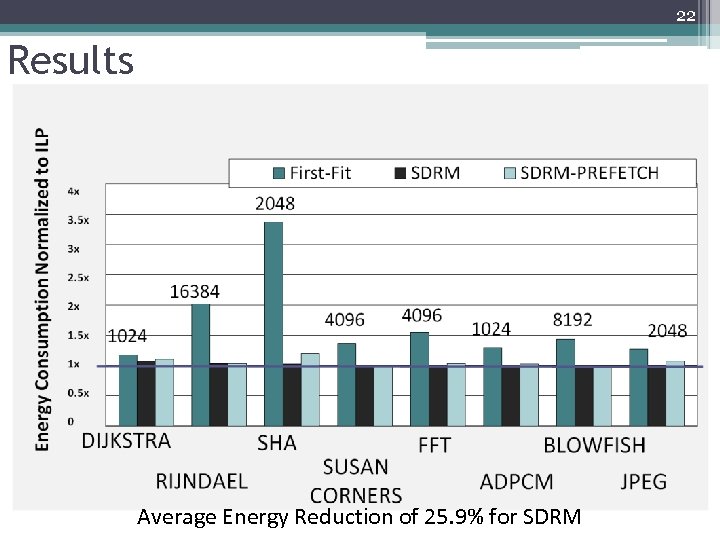

22 Results Average Energy Reduction of 25. 9% for SDRM

22 Results Average Energy Reduction of 25. 9% for SDRM

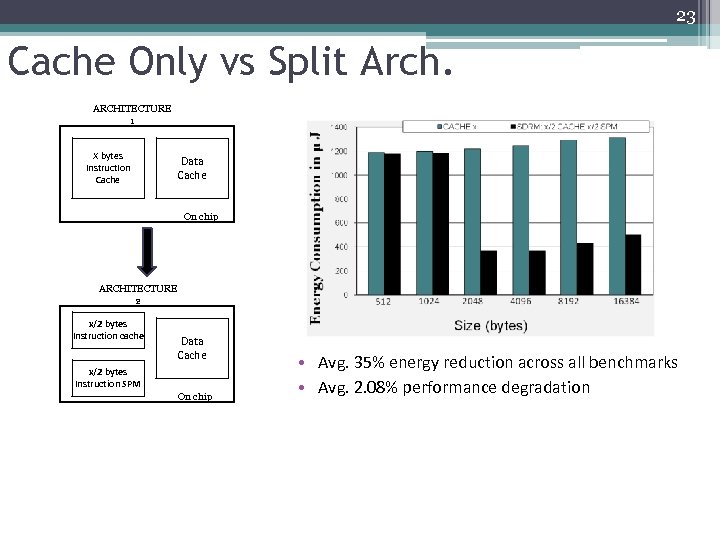

23 Cache Only vs Split Arch. ARCHITECTURE 1 X bytes Instruction Cache Data Cache On chip ARCHITECTURE 2 x/2 bytes Instruction cache Data Cache x/2 bytes Instruction SPM On chip • Avg. 35% energy reduction across all benchmarks • Avg. 2. 08% performance degradation

23 Cache Only vs Split Arch. ARCHITECTURE 1 X bytes Instruction Cache Data Cache On chip ARCHITECTURE 2 x/2 bytes Instruction cache Data Cache x/2 bytes Instruction SPM On chip • Avg. 35% energy reduction across all benchmarks • Avg. 2. 08% performance degradation

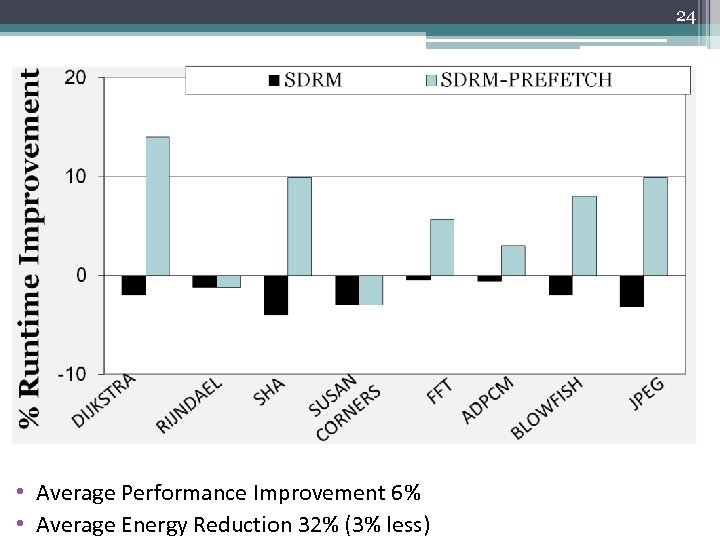

24 • Average Performance Improvement 6% • Average Energy Reduction 32% (3% less)

24 • Average Performance Improvement 6% • Average Energy Reduction 32% (3% less)

Conclusion • By splitting an Instruction Cache into an equal sized SPM and I-Cache, a pure software technique like SDRM will always result in energy savings. • Tradeoff between energy savings and performance improvement. • SPM are the way to go for many-core architectures.

Conclusion • By splitting an Instruction Cache into an equal sized SPM and I-Cache, a pure software technique like SDRM will always result in energy savings. • Tradeoff between energy savings and performance improvement. • SPM are the way to go for many-core architectures.

26 Continuing Effort • Improve static analysis • Investigate effect of outlining on the mapping function • Explore techniques to use and share SPM in a multi-core and multi-tasking environment

26 Continuing Effort • Improve static analysis • Investigate effect of outlining on the mapping function • Explore techniques to use and share SPM in a multi-core and multi-tasking environment

27 References 1. New Microarchitecture Challenges for the Coming Generations of CMOS Process Technologies. Micro 32. 2. GROCHOWSKI, E. , RONEN, R. , SHEN, J. , WANG, H. 2004. Best of Both Latency and Throughput. 2004 IEEE International Conference on Computer Design (ICCD ‘ 04), 236243. 3. S. Steinke et al. : Assigning program and data objects to scratchpad memory for energy reduction. 4. F. Angiolini et al: A post-compiler approach to scratchpad mapping code. 5. B Egger, S. L. Min et al. : A dynamic code placement technique for scratchpad memory using postpass optimization 6. B Egger et al : Scratchpad memory management for portable systems with a memory management unit 7. M. Verma et al. : Dynamic overlay of scratchpad memory for energy minimization 8. M. Verma and P. Marwedel : Overlay techniques for scratchpad memories in low power embedded processors* 9. S. Steinke et al. : Reducing energy consumption by dynamic copying of instructions onto onchip memory 10. A. Udayakumaran and R. Barua: Dynamic Allocation for Scratch-Pad Memory using Compile-time Decisions

27 References 1. New Microarchitecture Challenges for the Coming Generations of CMOS Process Technologies. Micro 32. 2. GROCHOWSKI, E. , RONEN, R. , SHEN, J. , WANG, H. 2004. Best of Both Latency and Throughput. 2004 IEEE International Conference on Computer Design (ICCD ‘ 04), 236243. 3. S. Steinke et al. : Assigning program and data objects to scratchpad memory for energy reduction. 4. F. Angiolini et al: A post-compiler approach to scratchpad mapping code. 5. B Egger, S. L. Min et al. : A dynamic code placement technique for scratchpad memory using postpass optimization 6. B Egger et al : Scratchpad memory management for portable systems with a memory management unit 7. M. Verma et al. : Dynamic overlay of scratchpad memory for energy minimization 8. M. Verma and P. Marwedel : Overlay techniques for scratchpad memories in low power embedded processors* 9. S. Steinke et al. : Reducing energy consumption by dynamic copying of instructions onto onchip memory 10. A. Udayakumaran and R. Barua: Dynamic Allocation for Scratch-Pad Memory using Compile-time Decisions

28 Research Papers • SDRM: Simultaneous Determination of Regions and Function-to-Region Mapping for Scratchpad Memories ▫ International Conference on High Performance Computing 2008 – First Author • A Software Solution for Dynamic Stack Management on Scratchpad Memory ▫ Asia and South Pacific Design Automation Conference 2009 – Co-author • A Dynamic Code Mapping Technique for Scratchpad Memories in Embedded Systems ▫ Submitted to IEEE Trans. On Computer Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems

28 Research Papers • SDRM: Simultaneous Determination of Regions and Function-to-Region Mapping for Scratchpad Memories ▫ International Conference on High Performance Computing 2008 – First Author • A Software Solution for Dynamic Stack Management on Scratchpad Memory ▫ Asia and South Pacific Design Automation Conference 2009 – Co-author • A Dynamic Code Mapping Technique for Scratchpad Memories in Embedded Systems ▫ Submitted to IEEE Trans. On Computer Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems

29 Thank you!

29 Thank you!