Agatha Christie Life and career Early life and

25702-agatha_christie.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 15

Agatha Christie

Agatha Christie

Life and career Early life and first marriage Agatha Mary Clarissa Miller was born in Torquay, Devon, England, UK. Her mother, Clarissa Margaret Boehmer, was the daughter of a British Army captain but had been sent as a child to live with her own mother's sister, who was the second wife of a wealthy American. Eventually Margaret married her stepfather's son from his first marriage, Frederick Alvah Miller, an American stockbroker. Thus, the two women Agatha called "Grannie" were sisters. Despite her father's nationality as a "New Yorker" and her aunt's relation to the Pierpont Morgans, Agatha never claimed United States citizenship or connection. Agatha was the youngest of three. The Millers had two other children: Margaret Frary Miller (1879–1950), called Madge, who was 11 years Agatha's senior, and Louis Montant Miller (1880–1929), called Monty, 10 years older than Agatha. Later, in her autobiography, Agatha would refer to her brother as "an amiable scapegrace of a brother". Agatha described herself as having had a very happy childhood. While she never received any formal schooling, she did not lack an education. Her mother believed children should not learn to read until they were eight, but Agatha taught herself to read at four. Her father taught her mathematics via story problems, and the family played question-and-answer games much like today's Trivial Pursuit. She had piano lessons, which she liked, and dance lessons, which she did not. When she could not learn French through formal instruction, the family hired a young woman who spoke nothing but French to be her nanny and companion. Agatha made up stories from a very early age and invented a number of imaginary friends and paracosms. One of them, "The School", with a dozen or so imaginary young women of widely varying temperaments, lasted well into her adult years.

Life and career Early life and first marriage Agatha Mary Clarissa Miller was born in Torquay, Devon, England, UK. Her mother, Clarissa Margaret Boehmer, was the daughter of a British Army captain but had been sent as a child to live with her own mother's sister, who was the second wife of a wealthy American. Eventually Margaret married her stepfather's son from his first marriage, Frederick Alvah Miller, an American stockbroker. Thus, the two women Agatha called "Grannie" were sisters. Despite her father's nationality as a "New Yorker" and her aunt's relation to the Pierpont Morgans, Agatha never claimed United States citizenship or connection. Agatha was the youngest of three. The Millers had two other children: Margaret Frary Miller (1879–1950), called Madge, who was 11 years Agatha's senior, and Louis Montant Miller (1880–1929), called Monty, 10 years older than Agatha. Later, in her autobiography, Agatha would refer to her brother as "an amiable scapegrace of a brother". Agatha described herself as having had a very happy childhood. While she never received any formal schooling, she did not lack an education. Her mother believed children should not learn to read until they were eight, but Agatha taught herself to read at four. Her father taught her mathematics via story problems, and the family played question-and-answer games much like today's Trivial Pursuit. She had piano lessons, which she liked, and dance lessons, which she did not. When she could not learn French through formal instruction, the family hired a young woman who spoke nothing but French to be her nanny and companion. Agatha made up stories from a very early age and invented a number of imaginary friends and paracosms. One of them, "The School", with a dozen or so imaginary young women of widely varying temperaments, lasted well into her adult years.

Agatha described herself as having had a very happy childhood. While she never received any formal schooling, she did not lack an education. Her mother believed children should not learn to read until they were eight, but Agatha taught herself to read at four. Her father taught her mathematics via story problems, and the family played question-and-answer games much like today's Trivial Pursuit. She had piano lessons, which she liked, and dance lessons, which she did not. When she could not learn French through formal instruction, the family hired a young woman who spoke nothing but French to be her nanny and companion. Agatha made up stories from a very early age and invented a number of imaginary friends and paracosms. One of them, "The School", with a dozen or so imaginary young women of widely varying temperaments, lasted well into her adult years.

Agatha described herself as having had a very happy childhood. While she never received any formal schooling, she did not lack an education. Her mother believed children should not learn to read until they were eight, but Agatha taught herself to read at four. Her father taught her mathematics via story problems, and the family played question-and-answer games much like today's Trivial Pursuit. She had piano lessons, which she liked, and dance lessons, which she did not. When she could not learn French through formal instruction, the family hired a young woman who spoke nothing but French to be her nanny and companion. Agatha made up stories from a very early age and invented a number of imaginary friends and paracosms. One of them, "The School", with a dozen or so imaginary young women of widely varying temperaments, lasted well into her adult years.

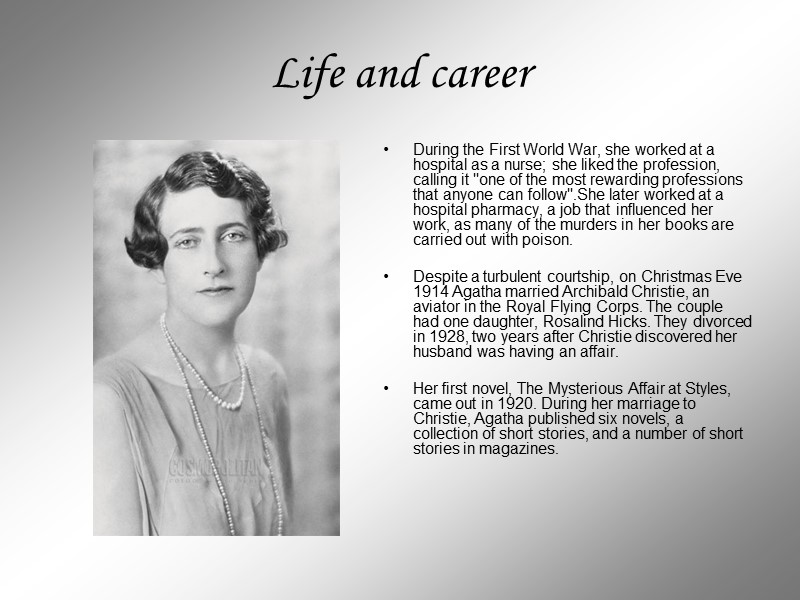

Life and career During the First World War, she worked at a hospital as a nurse; she liked the profession, calling it "one of the most rewarding professions that anyone can follow".She later worked at a hospital pharmacy, a job that influenced her work, as many of the murders in her books are carried out with poison. Despite a turbulent courtship, on Christmas Eve 1914 Agatha married Archibald Christie, an aviator in the Royal Flying Corps. The couple had one daughter, Rosalind Hicks. They divorced in 1928, two years after Christie discovered her husband was having an affair. Her first novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, came out in 1920. During her marriage to Christie, Agatha published six novels, a collection of short stories, and a number of short stories in magazines.

Life and career During the First World War, she worked at a hospital as a nurse; she liked the profession, calling it "one of the most rewarding professions that anyone can follow".She later worked at a hospital pharmacy, a job that influenced her work, as many of the murders in her books are carried out with poison. Despite a turbulent courtship, on Christmas Eve 1914 Agatha married Archibald Christie, an aviator in the Royal Flying Corps. The couple had one daughter, Rosalind Hicks. They divorced in 1928, two years after Christie discovered her husband was having an affair. Her first novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, came out in 1920. During her marriage to Christie, Agatha published six novels, a collection of short stories, and a number of short stories in magazines.

Disappearance In late 1926, Agatha's husband, Archie, revealed that he was in love with another woman, Nancy Neele, and wanted a divorce. On 8 December 1926 the couple quarreled, and Archie Christie left their house Styles in Sunningdale, Berkshire, to spend the weekend with his mistress at Godalming, Surrey. That same evening Agatha disappeared from her home, leaving behind a letter for her secretary saying that she was going to Yorkshire. Her disappearance caused an outcry from the public, many of whom were admirers of her novels. Despite a massive manhunt, she was not found for 11 days. On 19 December 1926 Agatha was identified as a guest at the Swan Hydropathic Hotel (now the Old Swan Hotel) in Harrogate, Yorkshire, where she was registered as 'Mrs Teresa Neele' from Cape Town. Agatha gave no account of her disappearance. Although two doctors had diagnosed her as suffering from psychogenic fugue, opinion remains divided as to the reasons for her disappearance. One suggestion is that she had suffered a nervous breakdown brought about by a natural propensity for depression, exacerbated by her mother's death earlier that year and the discovery of her husband's infidelity. Public reaction at the time was largely negative, with many believing it a publicity stunt while others speculated she was trying to make the police believe her husband had killed her. Author Jared Cade interviewed numerous witnesses and relatives for his sympathetic biography, Agatha Christie and the Missing Eleven Days, and provided a substantial amount of evidence to suggest that Christie planned the entire disappearance to embarrass her husband, never thinking it would escalate into the melodrama it became.

Disappearance In late 1926, Agatha's husband, Archie, revealed that he was in love with another woman, Nancy Neele, and wanted a divorce. On 8 December 1926 the couple quarreled, and Archie Christie left their house Styles in Sunningdale, Berkshire, to spend the weekend with his mistress at Godalming, Surrey. That same evening Agatha disappeared from her home, leaving behind a letter for her secretary saying that she was going to Yorkshire. Her disappearance caused an outcry from the public, many of whom were admirers of her novels. Despite a massive manhunt, she was not found for 11 days. On 19 December 1926 Agatha was identified as a guest at the Swan Hydropathic Hotel (now the Old Swan Hotel) in Harrogate, Yorkshire, where she was registered as 'Mrs Teresa Neele' from Cape Town. Agatha gave no account of her disappearance. Although two doctors had diagnosed her as suffering from psychogenic fugue, opinion remains divided as to the reasons for her disappearance. One suggestion is that she had suffered a nervous breakdown brought about by a natural propensity for depression, exacerbated by her mother's death earlier that year and the discovery of her husband's infidelity. Public reaction at the time was largely negative, with many believing it a publicity stunt while others speculated she was trying to make the police believe her husband had killed her. Author Jared Cade interviewed numerous witnesses and relatives for his sympathetic biography, Agatha Christie and the Missing Eleven Days, and provided a substantial amount of evidence to suggest that Christie planned the entire disappearance to embarrass her husband, never thinking it would escalate into the melodrama it became.

Second marriage and later life In 1930, Christie married archaeologist Max Mallowan (Sir Max from 1968) after joining him in an archaeological dig. Their marriage was especially happy in the early years and remained so until Christie's death in 1976. In 1977, Mallowan married his longtime associate, Barbara Parker. Christie frequently used settings which were familiar to her for her stories. Christie's travels with Mallowan contributed background to several of her novels set in the Middle East. Other novels (such as And Then There Were None) were set in and around Torquay, where she was born. Christie's 1934 novel Murder on the Orient Express was written in the Hotel Pera Palace in Istanbul, Turkey, the southern terminus of the railway. The hotel maintains Christie's room as a memorial to the author. The Greenway Estate in Devon, acquired by the couple as a summer residence in 1938, is now in the care of the National Trust. Christie often stayed at Abney Hall in Cheshire, which was owned by her brother-in-law, James Watts. She based at least two of her stories on the hall: the short story The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding, which is in the story collection of the same name, and the novel After the Funeral. "Abney became Agatha's greatest inspiration for country-house life, with all the servants and grandeur which have been woven into her plots. The descriptions of the fictional Chimneys, Stoneygates, and other houses in her stories are mostly Abney in various forms."

Second marriage and later life In 1930, Christie married archaeologist Max Mallowan (Sir Max from 1968) after joining him in an archaeological dig. Their marriage was especially happy in the early years and remained so until Christie's death in 1976. In 1977, Mallowan married his longtime associate, Barbara Parker. Christie frequently used settings which were familiar to her for her stories. Christie's travels with Mallowan contributed background to several of her novels set in the Middle East. Other novels (such as And Then There Were None) were set in and around Torquay, where she was born. Christie's 1934 novel Murder on the Orient Express was written in the Hotel Pera Palace in Istanbul, Turkey, the southern terminus of the railway. The hotel maintains Christie's room as a memorial to the author. The Greenway Estate in Devon, acquired by the couple as a summer residence in 1938, is now in the care of the National Trust. Christie often stayed at Abney Hall in Cheshire, which was owned by her brother-in-law, James Watts. She based at least two of her stories on the hall: the short story The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding, which is in the story collection of the same name, and the novel After the Funeral. "Abney became Agatha's greatest inspiration for country-house life, with all the servants and grandeur which have been woven into her plots. The descriptions of the fictional Chimneys, Stoneygates, and other houses in her stories are mostly Abney in various forms."

Second marriage and later life During the Second World War, Christie worked in the pharmacy at University College Hospital, London, where she acquired a knowledge of poisons that she put to good use in her post-war crime novels. For example, the use of thallium as a poison was suggested to her by UCH Chief Pharmacist Harold Davis (later appointed Chief Pharmacist at the UK Ministry of Health), and in The Pale Horse, published in 1961, she employed it to dispatch a series of victims, the first clue to the murder method coming from the victims’ loss of hair. So accurate was her description of thallium poisoning that on at least one occasion it helped solve a case that was baffling doctors. To honour her many literary works, she was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire in the 1956 New Year Honours. The next year, she became the President of the Detection Club. In the 1971 New Year Honours she was promoted Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire, three years after her husband had been knighted for his archeological work in 1968. They were one of the few married couples where both partners were honoured in their own right. From 1968, due to her husband's knighthood, Christie could also be styled as Lady Agatha Mallowan, or simply Lady Mallowan. Agatha Christie's gravestone in Cholsey. From 1971 to 1974, Christie's health began to fail, although she continued to write. In 1975, sensing her increasing weakness, Christie signed over the rights of her most successful play, The Mousetrap, to her grandson.Recently, using experimental textual tools of analysis, Canadian researchers have suggested that Christie may have begun to suffer from Alzheimer's disease or other dementia. Agatha Christie died on 12 January 1976 at age 85 from natural causes at her Winterbrook House in the north of Cholsey parish, adjoining Wallingford in Oxfordshire (formerly part of Berkshire). She is buried in the nearby churchyard of St Mary's, Cholsey. Christie's only child, Rosalind Margaret Hicks, died, also aged 85, on 28 October 2004 from natural causes in Torbay, Devon. Christie's grandson, Mathew Prichard, was heir to the copyright to some of his grandmother's literary work (including The Mousetrap) and is still associated with Agatha Christie Limited.

Second marriage and later life During the Second World War, Christie worked in the pharmacy at University College Hospital, London, where she acquired a knowledge of poisons that she put to good use in her post-war crime novels. For example, the use of thallium as a poison was suggested to her by UCH Chief Pharmacist Harold Davis (later appointed Chief Pharmacist at the UK Ministry of Health), and in The Pale Horse, published in 1961, she employed it to dispatch a series of victims, the first clue to the murder method coming from the victims’ loss of hair. So accurate was her description of thallium poisoning that on at least one occasion it helped solve a case that was baffling doctors. To honour her many literary works, she was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire in the 1956 New Year Honours. The next year, she became the President of the Detection Club. In the 1971 New Year Honours she was promoted Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire, three years after her husband had been knighted for his archeological work in 1968. They were one of the few married couples where both partners were honoured in their own right. From 1968, due to her husband's knighthood, Christie could also be styled as Lady Agatha Mallowan, or simply Lady Mallowan. Agatha Christie's gravestone in Cholsey. From 1971 to 1974, Christie's health began to fail, although she continued to write. In 1975, sensing her increasing weakness, Christie signed over the rights of her most successful play, The Mousetrap, to her grandson.Recently, using experimental textual tools of analysis, Canadian researchers have suggested that Christie may have begun to suffer from Alzheimer's disease or other dementia. Agatha Christie died on 12 January 1976 at age 85 from natural causes at her Winterbrook House in the north of Cholsey parish, adjoining Wallingford in Oxfordshire (formerly part of Berkshire). She is buried in the nearby churchyard of St Mary's, Cholsey. Christie's only child, Rosalind Margaret Hicks, died, also aged 85, on 28 October 2004 from natural causes in Torbay, Devon. Christie's grandson, Mathew Prichard, was heir to the copyright to some of his grandmother's literary work (including The Mousetrap) and is still associated with Agatha Christie Limited.

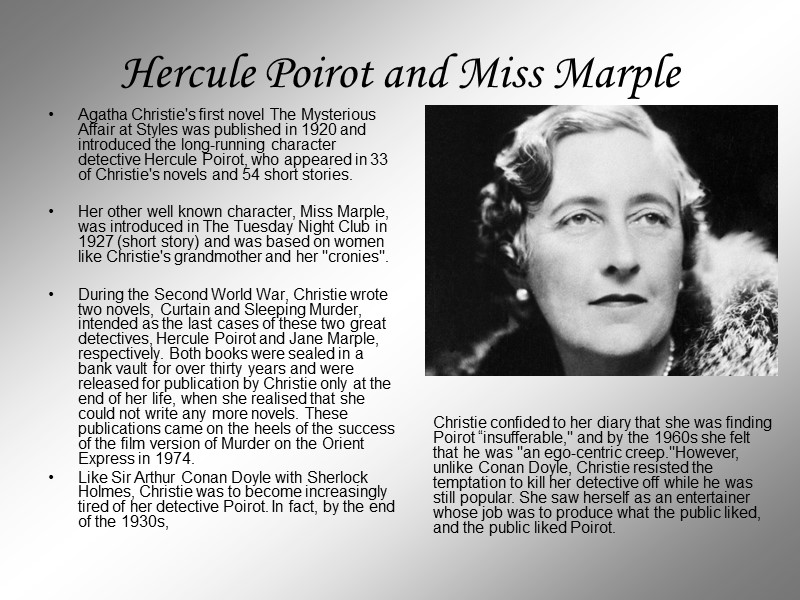

Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple Agatha Christie's first novel The Mysterious Affair at Styles was published in 1920 and introduced the long-running character detective Hercule Poirot, who appeared in 33 of Christie's novels and 54 short stories. Her other well known character, Miss Marple, was introduced in The Tuesday Night Club in 1927 (short story) and was based on women like Christie's grandmother and her "cronies". During the Second World War, Christie wrote two novels, Curtain and Sleeping Murder, intended as the last cases of these two great detectives, Hercule Poirot and Jane Marple, respectively. Both books were sealed in a bank vault for over thirty years and were released for publication by Christie only at the end of her life, when she realised that she could not write any more novels. These publications came on the heels of the success of the film version of Murder on the Orient Express in 1974. Like Sir Arthur Conan Doyle with Sherlock Holmes, Christie was to become increasingly tired of her detective Poirot. In fact, by the end of the 1930s, Christie confided to her diary that she was finding Poirot “insufferable," and by the 1960s she felt that he was "an ego-centric creep."However, unlike Conan Doyle, Christie resisted the temptation to kill her detective off while he was still popular. She saw herself as an entertainer whose job was to produce what the public liked, and the public liked Poirot.

Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple Agatha Christie's first novel The Mysterious Affair at Styles was published in 1920 and introduced the long-running character detective Hercule Poirot, who appeared in 33 of Christie's novels and 54 short stories. Her other well known character, Miss Marple, was introduced in The Tuesday Night Club in 1927 (short story) and was based on women like Christie's grandmother and her "cronies". During the Second World War, Christie wrote two novels, Curtain and Sleeping Murder, intended as the last cases of these two great detectives, Hercule Poirot and Jane Marple, respectively. Both books were sealed in a bank vault for over thirty years and were released for publication by Christie only at the end of her life, when she realised that she could not write any more novels. These publications came on the heels of the success of the film version of Murder on the Orient Express in 1974. Like Sir Arthur Conan Doyle with Sherlock Holmes, Christie was to become increasingly tired of her detective Poirot. In fact, by the end of the 1930s, Christie confided to her diary that she was finding Poirot “insufferable," and by the 1960s she felt that he was "an ego-centric creep."However, unlike Conan Doyle, Christie resisted the temptation to kill her detective off while he was still popular. She saw herself as an entertainer whose job was to produce what the public liked, and the public liked Poirot.

Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple In contrast, Christie was fond of Miss Marple. However, it is interesting to note that the Belgian detective’s titles outnumber the Marple titles more than two to one. This is largely because Christie wrote numerous Poirot novels early in her career, while The Murder at the Vicarage remained the sole Marple novel until the 1940s. Christie never wrote a novel or short story featuring both Poirot and Miss Marple. In a recording, recently rediscovered and released in 2008, Christie revealed the reason for this: "Hercule Poirot, a complete egoist, would not like being taught his business or having suggestions made to him by an elderly spinster lady". Poirot is the only fictional character to have been given an obituary in The New York Times, following the publication of Curtain in 1975. Following the great success of Curtain, Dame Agatha gave permission for the release of Sleeping Murder sometime in 1976 but died in January 1976 before the book could be released. This may explain some of the inconsistencies compared to the rest of the Marple series — for example, Colonel Arthur Bantry, husband of Miss Marple's friend Dolly, is still alive and well in Sleeping Murder despite the fact he is noted as having died in books published earlier. It may be that Christie simply did not have time to revise the manuscript before she died. Miss Marple fared better than Poirot, since after solving the mystery in Sleeping Murder she returns home to her regular life in St. Mary Mead. On an edition of Desert Island Discs in 2007, Brian Aldiss claimed that Agatha Christie told him that she wrote her books up to the last chapter and then decided who the most unlikely suspect was. She would then go back and make the necessary changes to "frame" that person.[32] The evidence of Christie's working methods, as described by successive biographers, contradicts this claim.

Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple In contrast, Christie was fond of Miss Marple. However, it is interesting to note that the Belgian detective’s titles outnumber the Marple titles more than two to one. This is largely because Christie wrote numerous Poirot novels early in her career, while The Murder at the Vicarage remained the sole Marple novel until the 1940s. Christie never wrote a novel or short story featuring both Poirot and Miss Marple. In a recording, recently rediscovered and released in 2008, Christie revealed the reason for this: "Hercule Poirot, a complete egoist, would not like being taught his business or having suggestions made to him by an elderly spinster lady". Poirot is the only fictional character to have been given an obituary in The New York Times, following the publication of Curtain in 1975. Following the great success of Curtain, Dame Agatha gave permission for the release of Sleeping Murder sometime in 1976 but died in January 1976 before the book could be released. This may explain some of the inconsistencies compared to the rest of the Marple series — for example, Colonel Arthur Bantry, husband of Miss Marple's friend Dolly, is still alive and well in Sleeping Murder despite the fact he is noted as having died in books published earlier. It may be that Christie simply did not have time to revise the manuscript before she died. Miss Marple fared better than Poirot, since after solving the mystery in Sleeping Murder she returns home to her regular life in St. Mary Mead. On an edition of Desert Island Discs in 2007, Brian Aldiss claimed that Agatha Christie told him that she wrote her books up to the last chapter and then decided who the most unlikely suspect was. She would then go back and make the necessary changes to "frame" that person.[32] The evidence of Christie's working methods, as described by successive biographers, contradicts this claim.

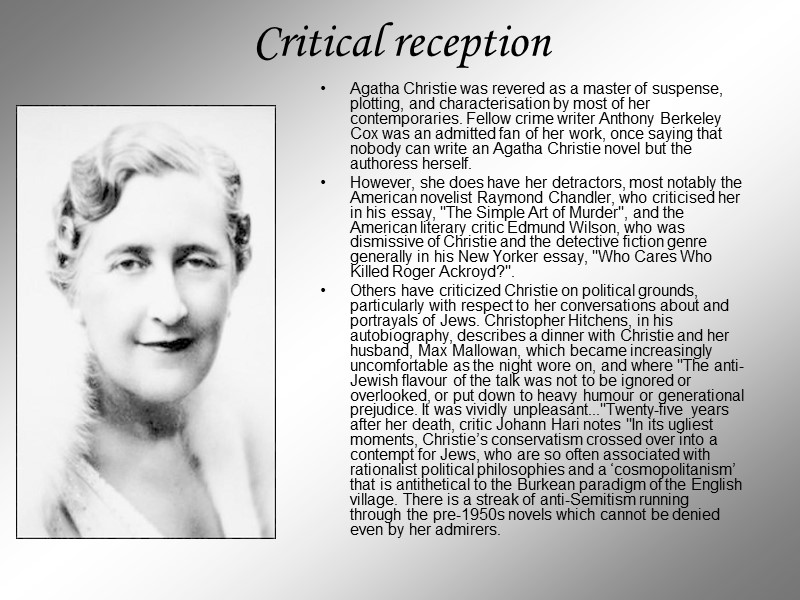

Critical reception Agatha Christie was revered as a master of suspense, plotting, and characterisation by most of her contemporaries. Fellow crime writer Anthony Berkeley Cox was an admitted fan of her work, once saying that nobody can write an Agatha Christie novel but the authoress herself. However, she does have her detractors, most notably the American novelist Raymond Chandler, who criticised her in his essay, "The Simple Art of Murder", and the American literary critic Edmund Wilson, who was dismissive of Christie and the detective fiction genre generally in his New Yorker essay, "Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?". Others have criticized Christie on political grounds, particularly with respect to her conversations about and portrayals of Jews. Christopher Hitchens, in his autobiography, describes a dinner with Christie and her husband, Max Mallowan, which became increasingly uncomfortable as the night wore on, and where "The anti-Jewish flavour of the talk was not to be ignored or overlooked, or put down to heavy humour or generational prejudice. It was vividly unpleasant..."Twenty-five years after her death, critic Johann Hari notes "In its ugliest moments, Christie’s conservatism crossed over into a contempt for Jews, who are so often associated with rationalist political philosophies and a ‘cosmopolitanism’ that is antithetical to the Burkean paradigm of the English village. There is a streak of anti-Semitism running through the pre-1950s novels which cannot be denied even by her admirers.

Critical reception Agatha Christie was revered as a master of suspense, plotting, and characterisation by most of her contemporaries. Fellow crime writer Anthony Berkeley Cox was an admitted fan of her work, once saying that nobody can write an Agatha Christie novel but the authoress herself. However, she does have her detractors, most notably the American novelist Raymond Chandler, who criticised her in his essay, "The Simple Art of Murder", and the American literary critic Edmund Wilson, who was dismissive of Christie and the detective fiction genre generally in his New Yorker essay, "Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?". Others have criticized Christie on political grounds, particularly with respect to her conversations about and portrayals of Jews. Christopher Hitchens, in his autobiography, describes a dinner with Christie and her husband, Max Mallowan, which became increasingly uncomfortable as the night wore on, and where "The anti-Jewish flavour of the talk was not to be ignored or overlooked, or put down to heavy humour or generational prejudice. It was vividly unpleasant..."Twenty-five years after her death, critic Johann Hari notes "In its ugliest moments, Christie’s conservatism crossed over into a contempt for Jews, who are so often associated with rationalist political philosophies and a ‘cosmopolitanism’ that is antithetical to the Burkean paradigm of the English village. There is a streak of anti-Semitism running through the pre-1950s novels which cannot be denied even by her admirers.

Stereotyping Christie occasionally inserted stereotyped descriptions of characters into her work, particularly before the end of the Second World War (when such attitudes were more commonly expressed publicly), and particularly in regard to Italians, Jews, and non-Europeans. For example, in the first editions of the collection The Mysterious Mr Quin (1930), in the short story "The Soul of the Croupier," she described "Hebraic men with hook-noses wearing rather flamboyant jewellery"; in later editions the passage was edited to describe "sallow men" wearing same. To contrast with the more stereotyped descriptions, Christie often characterised the "foreigners" in such a way as to make the reader understand and sympathise with them; this is particularly true of her Jewish characters, who are seldom actually criminals. (See, for example, the character of Oliver Manders in Three Act Tragedy.)

Stereotyping Christie occasionally inserted stereotyped descriptions of characters into her work, particularly before the end of the Second World War (when such attitudes were more commonly expressed publicly), and particularly in regard to Italians, Jews, and non-Europeans. For example, in the first editions of the collection The Mysterious Mr Quin (1930), in the short story "The Soul of the Croupier," she described "Hebraic men with hook-noses wearing rather flamboyant jewellery"; in later editions the passage was edited to describe "sallow men" wearing same. To contrast with the more stereotyped descriptions, Christie often characterised the "foreigners" in such a way as to make the reader understand and sympathise with them; this is particularly true of her Jewish characters, who are seldom actually criminals. (See, for example, the character of Oliver Manders in Three Act Tragedy.)

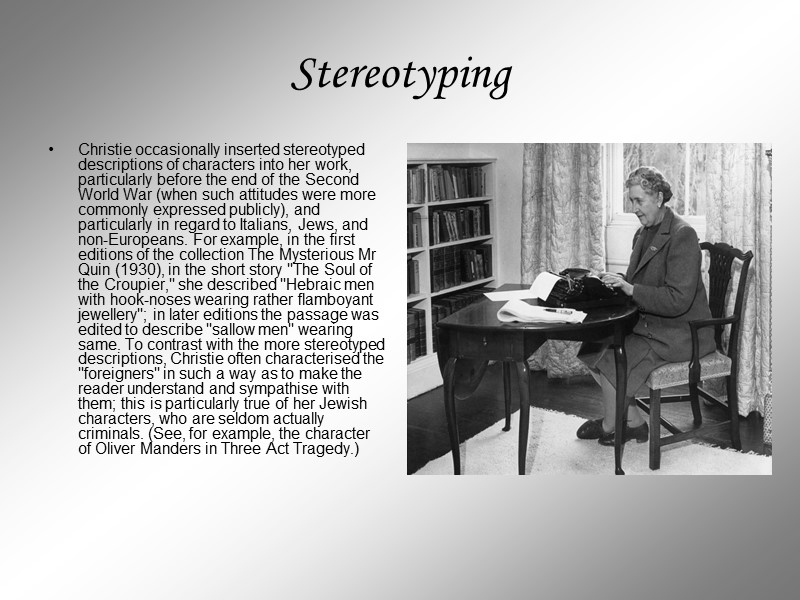

Novels written as Mary Westmacott 1930 Giant's Bread 1934 Unfinished Portrait 1944 Absent in the Spring 1948 The Rose and the Yew Tree 1952 A Daughter's a Daughter 1956 The Burden

Novels written as Mary Westmacott 1930 Giant's Bread 1934 Unfinished Portrait 1944 Absent in the Spring 1948 The Rose and the Yew Tree 1952 A Daughter's a Daughter 1956 The Burden

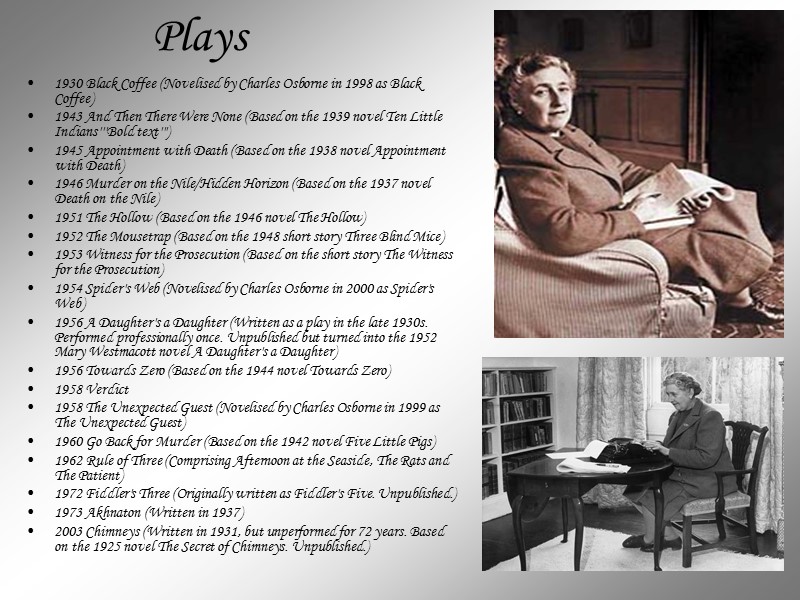

Plays 1930 Black Coffee (Novelised by Charles Osborne in 1998 as Black Coffee) 1943 And Then There Were None (Based on the 1939 novel Ten Little Indians'''Bold text''') 1945 Appointment with Death (Based on the 1938 novel Appointment with Death) 1946 Murder on the Nile/Hidden Horizon (Based on the 1937 novel Death on the Nile) 1951 The Hollow (Based on the 1946 novel The Hollow) 1952 The Mousetrap (Based on the 1948 short story Three Blind Mice) 1953 Witness for the Prosecution (Based on the short story The Witness for the Prosecution) 1954 Spider's Web (Novelised by Charles Osborne in 2000 as Spider's Web) 1956 A Daughter's a Daughter (Written as a play in the late 1930s. Performed professionally once. Unpublished but turned into the 1952 Mary Westmacott novel A Daughter's a Daughter) 1956 Towards Zero (Based on the 1944 novel Towards Zero) 1958 Verdict 1958 The Unexpected Guest (Novelised by Charles Osborne in 1999 as The Unexpected Guest) 1960 Go Back for Murder (Based on the 1942 novel Five Little Pigs) 1962 Rule of Three (Comprising Afternoon at the Seaside, The Rats and The Patient) 1972 Fiddler's Three (Originally written as Fiddler's Five. Unpublished.) 1973 Akhnaton (Written in 1937) 2003 Chimneys (Written in 1931, but unperformed for 72 years. Based on the 1925 novel The Secret of Chimneys. Unpublished.)

Plays 1930 Black Coffee (Novelised by Charles Osborne in 1998 as Black Coffee) 1943 And Then There Were None (Based on the 1939 novel Ten Little Indians'''Bold text''') 1945 Appointment with Death (Based on the 1938 novel Appointment with Death) 1946 Murder on the Nile/Hidden Horizon (Based on the 1937 novel Death on the Nile) 1951 The Hollow (Based on the 1946 novel The Hollow) 1952 The Mousetrap (Based on the 1948 short story Three Blind Mice) 1953 Witness for the Prosecution (Based on the short story The Witness for the Prosecution) 1954 Spider's Web (Novelised by Charles Osborne in 2000 as Spider's Web) 1956 A Daughter's a Daughter (Written as a play in the late 1930s. Performed professionally once. Unpublished but turned into the 1952 Mary Westmacott novel A Daughter's a Daughter) 1956 Towards Zero (Based on the 1944 novel Towards Zero) 1958 Verdict 1958 The Unexpected Guest (Novelised by Charles Osborne in 1999 as The Unexpected Guest) 1960 Go Back for Murder (Based on the 1942 novel Five Little Pigs) 1962 Rule of Three (Comprising Afternoon at the Seaside, The Rats and The Patient) 1972 Fiddler's Three (Originally written as Fiddler's Five. Unpublished.) 1973 Akhnaton (Written in 1937) 2003 Chimneys (Written in 1931, but unperformed for 72 years. Based on the 1925 novel The Secret of Chimneys. Unpublished.)

Questions 1) When she was born 2) What is the name of her first novel 3) The most famous book written by her 4) How many children had she 5) When she died

Questions 1) When she was born 2) What is the name of her first novel 3) The most famous book written by her 4) How many children had she 5) When she died

THANK YOU FOR YOUR ATTENTION!

THANK YOU FOR YOUR ATTENTION!