d704d69093b7334ef885a417ce1ea941.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 71

Addressing Mental Health Disorders in the Classroom Richard Van Acker, Ed. D. Eryn Van Acker, M. Ed. University of Illinois at Chicago College of Education (M/C 147) 1040 W. Harrison Chicago, Illinois 60607 vanacker@uic. edu

Addressing Mental Health Disorders in the Classroom Richard Van Acker, Ed. D. Eryn Van Acker, M. Ed. University of Illinois at Chicago College of Education (M/C 147) 1040 W. Harrison Chicago, Illinois 60607 vanacker@uic. edu

Children’s Mental Health Impacts All Classrooms

Children’s Mental Health Impacts All Classrooms

Children’s Mental Health Impacts All Classrooms 27% of children 9, 11, and 13 years of age have a diagnosable mental health impairment. An additional 16% of children have impaired mental health but do not meet criteria for a disorder. 13% of children have one or both parents with MH concerns. The Great Smoky Mountain Study of Youth & CDC

Children’s Mental Health Impacts All Classrooms 27% of children 9, 11, and 13 years of age have a diagnosable mental health impairment. An additional 16% of children have impaired mental health but do not meet criteria for a disorder. 13% of children have one or both parents with MH concerns. The Great Smoky Mountain Study of Youth & CDC

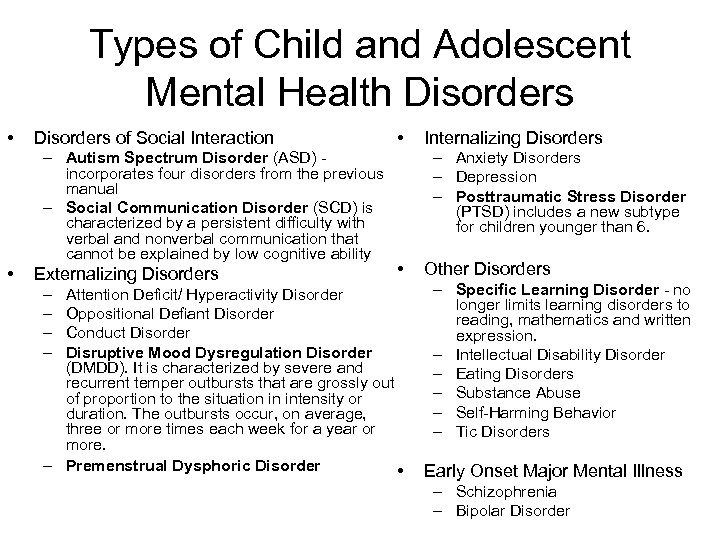

Types of Child and Adolescent Mental Health Disorders • Disorders of Social Interaction – Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) - incorporates four disorders from the previous manual – Social Communication Disorder (SCD) is characterized by a persistent difficulty with verbal and nonverbal communication that cannot be explained by low cognitive ability • Externalizing Disorders – – • Internalizing Disorders – Anxiety Disorders – Depression – Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) includes a new subtype for children younger than 6. • Attention Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder Oppositional Defiant Disorder Conduct Disorder Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (DMDD). It is characterized by severe and recurrent temper outbursts that are grossly out of proportion to the situation in intensity or duration. The outbursts occur, on average, three or more times each week for a year or more. – Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder • Other Disorders – Specific Learning Disorder - no longer limits learning disorders to reading, mathematics and written expression. – Intellectual Disability Disorder – Eating Disorders – Substance Abuse – Self-Harming Behavior – Tic Disorders Early Onset Major Mental Illness – Schizophrenia – Bipolar Disorder

Types of Child and Adolescent Mental Health Disorders • Disorders of Social Interaction – Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) - incorporates four disorders from the previous manual – Social Communication Disorder (SCD) is characterized by a persistent difficulty with verbal and nonverbal communication that cannot be explained by low cognitive ability • Externalizing Disorders – – • Internalizing Disorders – Anxiety Disorders – Depression – Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) includes a new subtype for children younger than 6. • Attention Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder Oppositional Defiant Disorder Conduct Disorder Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (DMDD). It is characterized by severe and recurrent temper outbursts that are grossly out of proportion to the situation in intensity or duration. The outbursts occur, on average, three or more times each week for a year or more. – Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder • Other Disorders – Specific Learning Disorder - no longer limits learning disorders to reading, mathematics and written expression. – Intellectual Disability Disorder – Eating Disorders – Substance Abuse – Self-Harming Behavior – Tic Disorders Early Onset Major Mental Illness – Schizophrenia – Bipolar Disorder

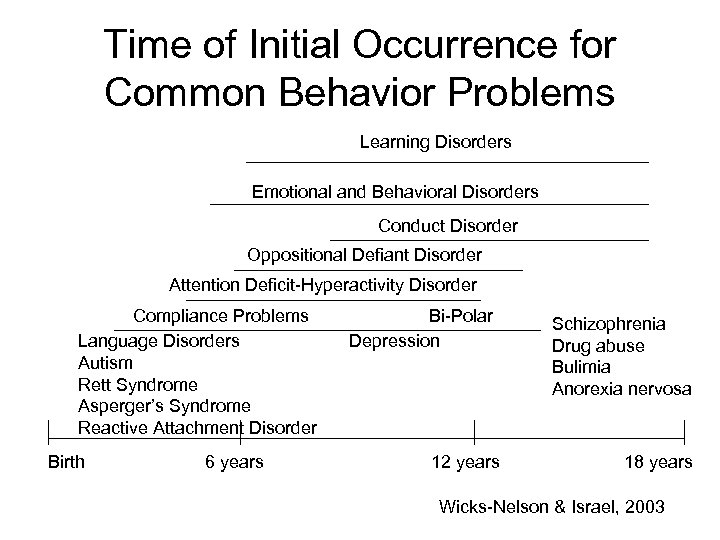

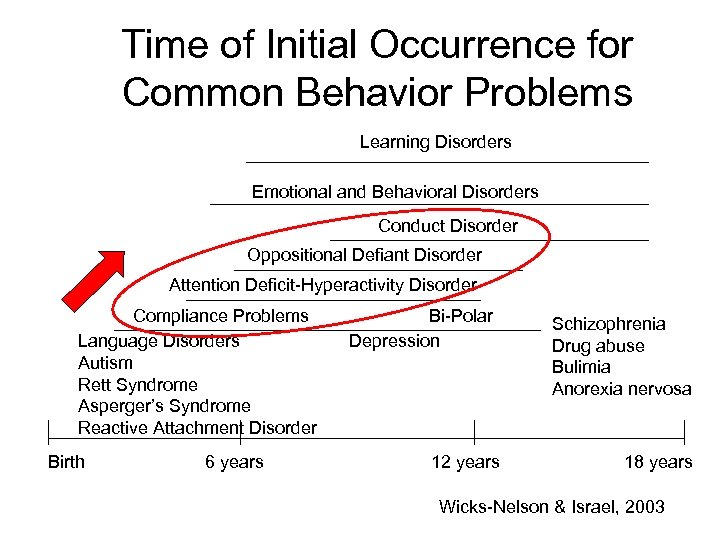

Time of Initial Occurrence for Common Behavior Problems Learning Disorders Emotional and Behavioral Disorders Conduct Disorder Oppositional Defiant Disorder Attention Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder Compliance Problems Bi-Polar Language Disorders Depression Autism Rett Syndrome Asperger’s Syndrome Reactive Attachment Disorder Birth 6 years Schizophrenia Drug abuse Bulimia Anorexia nervosa 12 years 18 years Wicks-Nelson & Israel, 2003

Time of Initial Occurrence for Common Behavior Problems Learning Disorders Emotional and Behavioral Disorders Conduct Disorder Oppositional Defiant Disorder Attention Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder Compliance Problems Bi-Polar Language Disorders Depression Autism Rett Syndrome Asperger’s Syndrome Reactive Attachment Disorder Birth 6 years Schizophrenia Drug abuse Bulimia Anorexia nervosa 12 years 18 years Wicks-Nelson & Israel, 2003

Time of Initial Occurrence for Common Behavior Problems Learning Disorders Emotional and Behavioral Disorders Conduct Disorder Oppositional Defiant Disorder Attention Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder Compliance Problems Bi-Polar Language Disorders Depression Autism Rett Syndrome Asperger’s Syndrome Reactive Attachment Disorder Birth 6 years Schizophrenia Drug abuse Bulimia Anorexia nervosa 12 years 18 years Wicks-Nelson & Israel, 2003

Time of Initial Occurrence for Common Behavior Problems Learning Disorders Emotional and Behavioral Disorders Conduct Disorder Oppositional Defiant Disorder Attention Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder Compliance Problems Bi-Polar Language Disorders Depression Autism Rett Syndrome Asperger’s Syndrome Reactive Attachment Disorder Birth 6 years Schizophrenia Drug abuse Bulimia Anorexia nervosa 12 years 18 years Wicks-Nelson & Israel, 2003

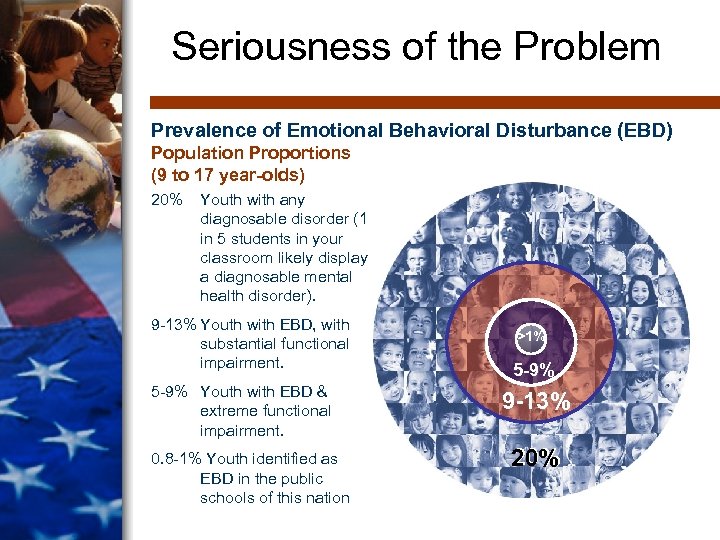

Seriousness of the Problem Prevalence of Emotional Behavioral Disturbance (EBD) Population Proportions (9 to 17 year-olds) 20% Youth with any diagnosable disorder (1 in 5 students in your classroom likely display a diagnosable mental health disorder). 9 -13% Youth with EBD, with substantial functional impairment. 5 -9% Youth with EBD & extreme functional impairment. 0. 8 -1% Youth identified as EBD in the public schools of this nation >1% 5 -9% 9 -13% 20%

Seriousness of the Problem Prevalence of Emotional Behavioral Disturbance (EBD) Population Proportions (9 to 17 year-olds) 20% Youth with any diagnosable disorder (1 in 5 students in your classroom likely display a diagnosable mental health disorder). 9 -13% Youth with EBD, with substantial functional impairment. 5 -9% Youth with EBD & extreme functional impairment. 0. 8 -1% Youth identified as EBD in the public schools of this nation >1% 5 -9% 9 -13% 20%

Diagnostic Dilemma • Regardless of the presenting symptoms, children and adolescents are most often initially referred for an evaluation for ADHD.

Diagnostic Dilemma • Regardless of the presenting symptoms, children and adolescents are most often initially referred for an evaluation for ADHD.

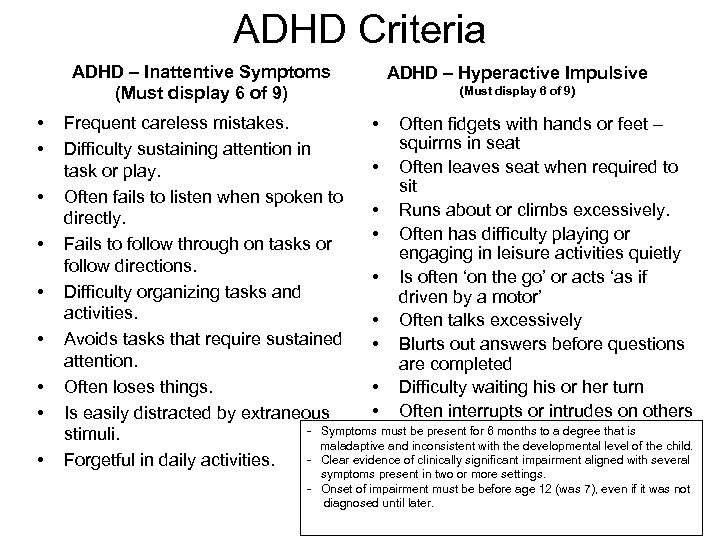

ADHD Criteria ADHD – Inattentive Symptoms (Must display 6 of 9) • • • ADHD – Hyperactive Impulsive (Must display 6 of 9) Frequent careless mistakes. • Often fidgets with hands or feet – squirms in seat Difficulty sustaining attention in • Often leaves seat when required to task or play. sit Often fails to listen when spoken to • Runs about or climbs excessively. directly. • Often has difficulty playing or Fails to follow through on tasks or engaging in leisure activities quietly follow directions. • Is often ‘on the go’ or acts ‘as if Difficulty organizing tasks and driven by a motor’ activities. • Often talks excessively Avoids tasks that require sustained • Blurts out answers before questions attention. are completed Often loses things. • Difficulty waiting his or her turn • Often interrupts or intrudes on others Is easily distracted by extraneous - Symptoms must be present for 6 months to a degree that is stimuli. maladaptive and inconsistent with the developmental level of the child. - Clear evidence of clinically significant impairment aligned with several Forgetful in daily activities. symptoms present in two or more settings. - Onset of impairment must be before age 12 (was 7), even if it was not diagnosed until later.

ADHD Criteria ADHD – Inattentive Symptoms (Must display 6 of 9) • • • ADHD – Hyperactive Impulsive (Must display 6 of 9) Frequent careless mistakes. • Often fidgets with hands or feet – squirms in seat Difficulty sustaining attention in • Often leaves seat when required to task or play. sit Often fails to listen when spoken to • Runs about or climbs excessively. directly. • Often has difficulty playing or Fails to follow through on tasks or engaging in leisure activities quietly follow directions. • Is often ‘on the go’ or acts ‘as if Difficulty organizing tasks and driven by a motor’ activities. • Often talks excessively Avoids tasks that require sustained • Blurts out answers before questions attention. are completed Often loses things. • Difficulty waiting his or her turn • Often interrupts or intrudes on others Is easily distracted by extraneous - Symptoms must be present for 6 months to a degree that is stimuli. maladaptive and inconsistent with the developmental level of the child. - Clear evidence of clinically significant impairment aligned with several Forgetful in daily activities. symptoms present in two or more settings. - Onset of impairment must be before age 12 (was 7), even if it was not diagnosed until later.

ADHD Epidemiology • Occurs in 3 – 12 % of school aged children and adolescents. • Boys are 4 to 9 times more likely to display ADHD than girls. Girls more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD Inattentive Type. • Thirty to 50% of individuals with ADHD display a co-morbid disorder (e. g. , ODD, CD, ASD, LD, Mood Disorders, Anxiety Disorders)

ADHD Epidemiology • Occurs in 3 – 12 % of school aged children and adolescents. • Boys are 4 to 9 times more likely to display ADHD than girls. Girls more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD Inattentive Type. • Thirty to 50% of individuals with ADHD display a co-morbid disorder (e. g. , ODD, CD, ASD, LD, Mood Disorders, Anxiety Disorders)

Medication and ADHD • Often educators express frustration in a parent’s reluctance to employ medication when their child suffers from ADHD. – Two general classes of medications for ADHD • Methylphenidate –Ritalin, Vyvanse, Concerta • Atomoxeline – Straterra, Clonidine, Intuniv – Only about 1/3 of children respond effectively to medication (some of these children may not actually suffer from ADHD) – Parents concerned about side effects (sleep problems, weight gain, eating disorders, etc. ) • Goal of medication = improved ability to attend

Medication and ADHD • Often educators express frustration in a parent’s reluctance to employ medication when their child suffers from ADHD. – Two general classes of medications for ADHD • Methylphenidate –Ritalin, Vyvanse, Concerta • Atomoxeline – Straterra, Clonidine, Intuniv – Only about 1/3 of children respond effectively to medication (some of these children may not actually suffer from ADHD) – Parents concerned about side effects (sleep problems, weight gain, eating disorders, etc. ) • Goal of medication = improved ability to attend

Adversity in Early Childhood • “Toxic stress” early in life can lead to fundamental changes in several regions of the brain, including those that subserve learning and memory (e. g. , hippocampus) and those that subserve executive functions (e. g. , various regions of the prefrontal cortex). • Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) Study Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, Walker JD, Whitfield C, et al. (2006) The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 256: 174 -186.

Adversity in Early Childhood • “Toxic stress” early in life can lead to fundamental changes in several regions of the brain, including those that subserve learning and memory (e. g. , hippocampus) and those that subserve executive functions (e. g. , various regions of the prefrontal cortex). • Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) Study Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, Walker JD, Whitfield C, et al. (2006) The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 256: 174 -186.

Measured the prevalence of eight adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), consisting of whether the child ever: 1. Lived with a parent or guardian who got divorced or separated; 2. Lived with a parent or guardian who died; 3. Lived with a parent or guardian who served time in jail or prison; 4. Lived with anyone who was mentally ill or suicidal, or severely depressed for more than a couple of weeks; 5. Lived with anyone who had a problem with alcohol or drugs; 6. Witnessed a parent, guardian, or other adult in the household behaving violently toward another (e. g. , slapping, hitting, kicking, punching, or beating each other up); 7. Was ever the victim of violence or witnessed any violence in his or her neighborhood; and 8. Experienced economic hardship “somewhat often” or “very often” (i. e. , the family found it hard to cover costs of food and housing).

Measured the prevalence of eight adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), consisting of whether the child ever: 1. Lived with a parent or guardian who got divorced or separated; 2. Lived with a parent or guardian who died; 3. Lived with a parent or guardian who served time in jail or prison; 4. Lived with anyone who was mentally ill or suicidal, or severely depressed for more than a couple of weeks; 5. Lived with anyone who had a problem with alcohol or drugs; 6. Witnessed a parent, guardian, or other adult in the household behaving violently toward another (e. g. , slapping, hitting, kicking, punching, or beating each other up); 7. Was ever the victim of violence or witnessed any violence in his or her neighborhood; and 8. Experienced economic hardship “somewhat often” or “very often” (i. e. , the family found it hard to cover costs of food and housing).

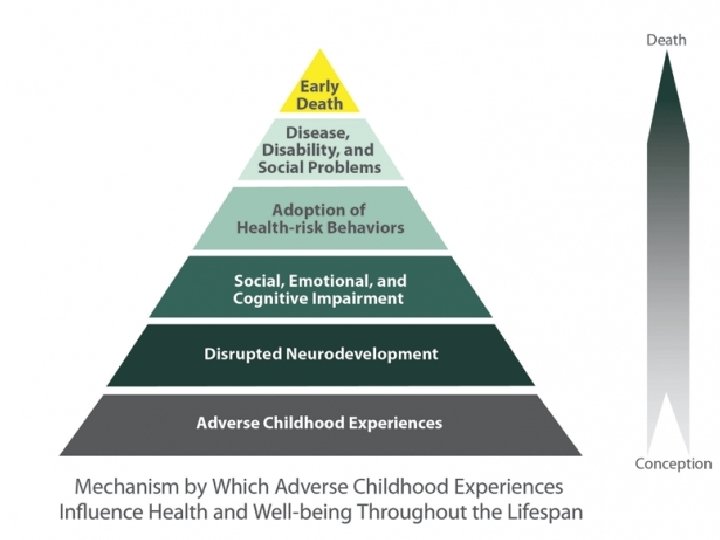

The ACE Pyramid represents the conceptual framework for the ACE Study. The ACE Study has uncovered how ACEs are strongly

The ACE Pyramid represents the conceptual framework for the ACE Study. The ACE Study has uncovered how ACEs are strongly

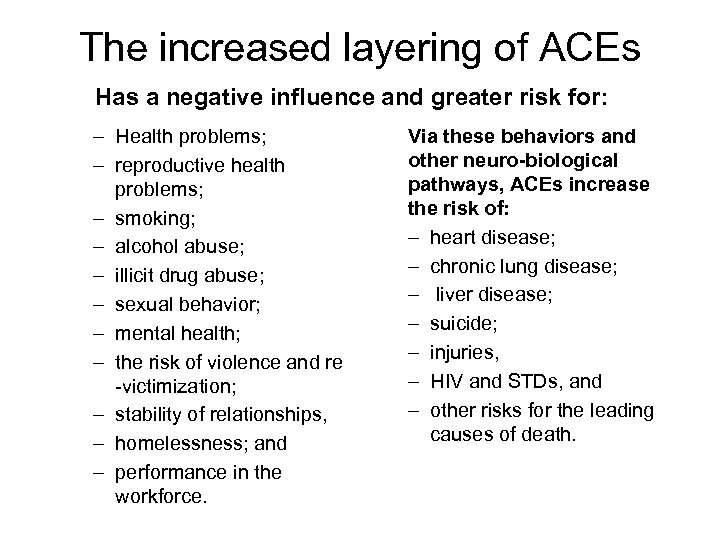

The increased layering of ACEs Has a negative influence and greater risk for: – Health problems; – reproductive health problems; – smoking; – alcohol abuse; – illicit drug abuse; – sexual behavior; – mental health; – the risk of violence and re -victimization; – stability of relationships, – homelessness; and – performance in the workforce. Via these behaviors and other neuro-biological pathways, ACEs increase the risk of: – heart disease; – chronic lung disease; – liver disease; – suicide; – injuries, – HIV and STDs, and – other risks for the leading causes of death.

The increased layering of ACEs Has a negative influence and greater risk for: – Health problems; – reproductive health problems; – smoking; – alcohol abuse; – illicit drug abuse; – sexual behavior; – mental health; – the risk of violence and re -victimization; – stability of relationships, – homelessness; and – performance in the workforce. Via these behaviors and other neuro-biological pathways, ACEs increase the risk of: – heart disease; – chronic lung disease; – liver disease; – suicide; – injuries, – HIV and STDs, and – other risks for the leading causes of death.

Oppositional Defiant Disorder • A pattern of negativistic, hostile and defiant behavior lasting greater than 6 months of which you have 4 or more of the following: – – – – Extreme loss of temper Argues with adults Actively defies or refuses to comply with rules Often deliberately annoys people Blames others for his or her mistakes Often touchy or easily annoyed with others Often angry or resentful Often spiteful or vindictive

Oppositional Defiant Disorder • A pattern of negativistic, hostile and defiant behavior lasting greater than 6 months of which you have 4 or more of the following: – – – – Extreme loss of temper Argues with adults Actively defies or refuses to comply with rules Often deliberately annoys people Blames others for his or her mistakes Often touchy or easily annoyed with others Often angry or resentful Often spiteful or vindictive

Biology of Oppositional Defiant Behavior Not just willful misbehavior/defiance • Strong genetic and biological basis – Neurotransmitters out of balance - Raising or lowering the level of neurotransmitters (i. e. , deviation from the norm) leads to a sudden change in mood and changes in the thinking process because of impaired transmission of nerve impulses. Higher levels of the neurotransmitter metabolizing enzyme monoamine oxidase-A (MAOA) related to aggressive responses are common. – Increased levels of testosterone – Low physiological arousal (under arousal) in response to stimulation • Sensation seeking to seek optimum arousal • Under reaction to guilt and anxiety – Deficiencies in the functioning of the prefrontal cortex, limiting the child’s reasoning, foresight, and ability to learn from experience. • That’s why people with ODD have: – a sense of irritation, – have no fear of punishment, and – often cannot adequately perceive reality or communicate normally.

Biology of Oppositional Defiant Behavior Not just willful misbehavior/defiance • Strong genetic and biological basis – Neurotransmitters out of balance - Raising or lowering the level of neurotransmitters (i. e. , deviation from the norm) leads to a sudden change in mood and changes in the thinking process because of impaired transmission of nerve impulses. Higher levels of the neurotransmitter metabolizing enzyme monoamine oxidase-A (MAOA) related to aggressive responses are common. – Increased levels of testosterone – Low physiological arousal (under arousal) in response to stimulation • Sensation seeking to seek optimum arousal • Under reaction to guilt and anxiety – Deficiencies in the functioning of the prefrontal cortex, limiting the child’s reasoning, foresight, and ability to learn from experience. • That’s why people with ODD have: – a sense of irritation, – have no fear of punishment, and – often cannot adequately perceive reality or communicate normally.

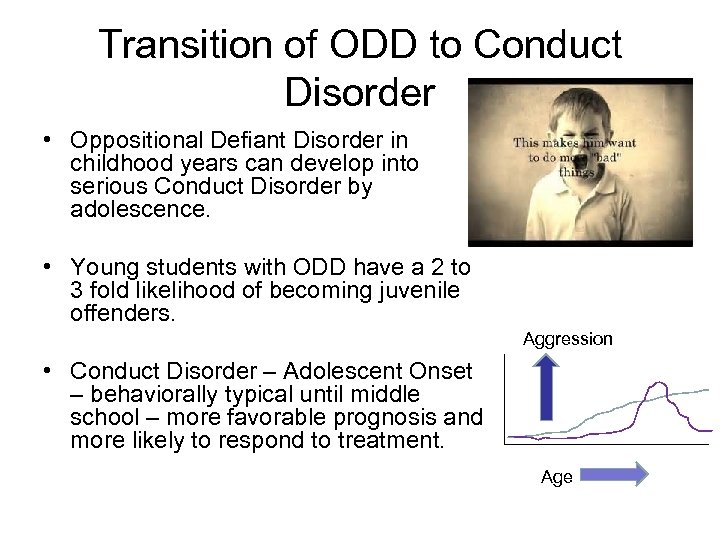

Transition of ODD to Conduct Disorder • Oppositional Defiant Disorder in childhood years can develop into serious Conduct Disorder by adolescence. • Young students with ODD have a 2 to 3 fold likelihood of becoming juvenile offenders. Aggression • Conduct Disorder – Adolescent Onset – behaviorally typical until middle school – more favorable prognosis and more likely to respond to treatment. Age

Transition of ODD to Conduct Disorder • Oppositional Defiant Disorder in childhood years can develop into serious Conduct Disorder by adolescence. • Young students with ODD have a 2 to 3 fold likelihood of becoming juvenile offenders. Aggression • Conduct Disorder – Adolescent Onset – behaviorally typical until middle school – more favorable prognosis and more likely to respond to treatment. Age

Conduct Disorder • Repetitive behaviors that violate the rights of others and/or societal laws, with 3 or more of the following in the past 12 months, with one in the last 6 months: – – Aggression or cruelty to people or animals Destruction of property Theft Running away • Affects 12% of boys and 7% of girls

Conduct Disorder • Repetitive behaviors that violate the rights of others and/or societal laws, with 3 or more of the following in the past 12 months, with one in the last 6 months: – – Aggression or cruelty to people or animals Destruction of property Theft Running away • Affects 12% of boys and 7% of girls

Oppositional Defiant Disorder and Conduct Disorder Treatment • Clear, brief, rules and expectations • Consistent and predictable consequences – Frequent recognition and praise for the display of desired behavior • Family therapy • Behavior management training – Collaborative Problem Solving (Ross Greene) • Social skills intervention • Social problem solving skill instruction

Oppositional Defiant Disorder and Conduct Disorder Treatment • Clear, brief, rules and expectations • Consistent and predictable consequences – Frequent recognition and praise for the display of desired behavior • Family therapy • Behavior management training – Collaborative Problem Solving (Ross Greene) • Social skills intervention • Social problem solving skill instruction

OCD – Medication and CBT • In a study of the glucose metabolism associated with the hyperactive neuronal activity associated with OCD found that treatment with medication (Prozac Family of Medications) and involvement in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy demonstrated essentially identical outcomes on PET scans. (Aboujaoude, 2009)

OCD – Medication and CBT • In a study of the glucose metabolism associated with the hyperactive neuronal activity associated with OCD found that treatment with medication (Prozac Family of Medications) and involvement in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy demonstrated essentially identical outcomes on PET scans. (Aboujaoude, 2009)

Anxiety Disorders • Incredibly strong feelings that situations are dangerous or threatening – These feelings have been demonstrated over an extended period of time – These feelings are triggered by ordinary things that don’t pose significant risk

Anxiety Disorders • Incredibly strong feelings that situations are dangerous or threatening – These feelings have been demonstrated over an extended period of time – These feelings are triggered by ordinary things that don’t pose significant risk

Types of Anxiety Disorders Generalized Anxiety Disorder • Children with a generalized anxiety disorder, or GAD, worry excessively about a variety of things such as grades, family issues, relationships with peers, and performance in sports. • Children with GAD tend to be very hard on themselves and strive for perfection. They may also seek constant approval or reassurance from others. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) • OCD is characterized by unwanted and intrusive thoughts (obsessions) and feeling compelled to repeatedly perform rituals and routines (compulsions) to try and ease anxiety. • Most children with OCD are diagnosed around age 10, although the disorder can strike children as young as two or three. Boys are more likely to develop OCD before puberty, while girls tend to develop it during adolescence. Panic Disorder • Panic disorder is diagnosed if a student suffers at least two unexpected panic or anxiety attacks—which means they come on suddenly and for no reason—followed by at least one month of concern over having another attack, losing control, or "going crazy. " Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) • Children with posttraumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, may have intense fear and anxiety, become emotionally numb or easily irritable, or avoid places, people, or activities after experiencing or witnessing a traumatic or life-threatening event.

Types of Anxiety Disorders Generalized Anxiety Disorder • Children with a generalized anxiety disorder, or GAD, worry excessively about a variety of things such as grades, family issues, relationships with peers, and performance in sports. • Children with GAD tend to be very hard on themselves and strive for perfection. They may also seek constant approval or reassurance from others. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) • OCD is characterized by unwanted and intrusive thoughts (obsessions) and feeling compelled to repeatedly perform rituals and routines (compulsions) to try and ease anxiety. • Most children with OCD are diagnosed around age 10, although the disorder can strike children as young as two or three. Boys are more likely to develop OCD before puberty, while girls tend to develop it during adolescence. Panic Disorder • Panic disorder is diagnosed if a student suffers at least two unexpected panic or anxiety attacks—which means they come on suddenly and for no reason—followed by at least one month of concern over having another attack, losing control, or "going crazy. " Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) • Children with posttraumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, may have intense fear and anxiety, become emotionally numb or easily irritable, or avoid places, people, or activities after experiencing or witnessing a traumatic or life-threatening event.

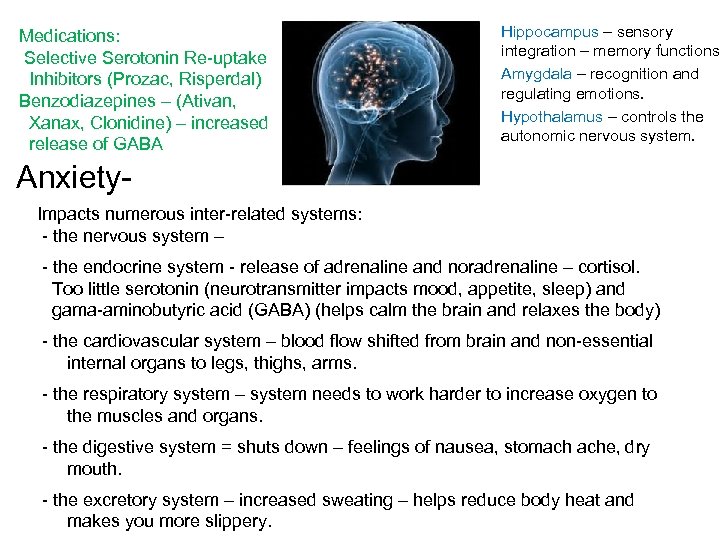

Medications: Selective Serotonin Re-uptake Inhibitors (Prozac, Risperdal) Benzodiazepines – (Ativan, Xanax, Clonidine) – increased release of GABA Hippocampus – sensory integration – memory functions Amygdala – recognition and regulating emotions. Hypothalamus – controls the autonomic nervous system. Anxiety- Impacts numerous inter-related systems: - the nervous system – - the endocrine system - release of adrenaline and noradrenaline – cortisol. Too little serotonin (neurotransmitter impacts mood, appetite, sleep) and gama-aminobutyric acid (GABA) (helps calm the brain and relaxes the body) - the cardiovascular system – blood flow shifted from brain and non-essential internal organs to legs, thighs, arms. - the respiratory system – system needs to work harder to increase oxygen to the muscles and organs. - the digestive system = shuts down – feelings of nausea, stomach ache, dry mouth. - the excretory system – increased sweating – helps reduce body heat and makes you more slippery.

Medications: Selective Serotonin Re-uptake Inhibitors (Prozac, Risperdal) Benzodiazepines – (Ativan, Xanax, Clonidine) – increased release of GABA Hippocampus – sensory integration – memory functions Amygdala – recognition and regulating emotions. Hypothalamus – controls the autonomic nervous system. Anxiety- Impacts numerous inter-related systems: - the nervous system – - the endocrine system - release of adrenaline and noradrenaline – cortisol. Too little serotonin (neurotransmitter impacts mood, appetite, sleep) and gama-aminobutyric acid (GABA) (helps calm the brain and relaxes the body) - the cardiovascular system – blood flow shifted from brain and non-essential internal organs to legs, thighs, arms. - the respiratory system – system needs to work harder to increase oxygen to the muscles and organs. - the digestive system = shuts down – feelings of nausea, stomach ache, dry mouth. - the excretory system – increased sweating – helps reduce body heat and makes you more slippery.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Core Treatment Elements • Information • Applied Relaxation • Cognitive Restructuring (probability estimates, coping estimates) • Cue-Controlled Worry (worry times + problem solving) • Worry Exposure (including existential topics) • Mindfulness • Medication – selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotoninnorepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, benzodiazepines, and tricyclic antidepressants [Fluxetine, Bur. Spar, Xanax, Ativan]

Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Core Treatment Elements • Information • Applied Relaxation • Cognitive Restructuring (probability estimates, coping estimates) • Cue-Controlled Worry (worry times + problem solving) • Worry Exposure (including existential topics) • Mindfulness • Medication – selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotoninnorepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, benzodiazepines, and tricyclic antidepressants [Fluxetine, Bur. Spar, Xanax, Ativan]

Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder • Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) is a childhood condition of extreme irritability, anger, and frequent, intense temper outbursts. DMDD symptoms go beyond a being a “moody” child— children with DMDD experience severe impairment that requires clinical attention. • Some of these children were previously diagnosed with bipolar disorder, even though they often did not have all the signs and symptoms. Research has also demonstrated that children with DMDD usually do not go on to have bipolar disorder in adulthood. They are more likely to develop problems with depression or anxiety.

Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder • Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) is a childhood condition of extreme irritability, anger, and frequent, intense temper outbursts. DMDD symptoms go beyond a being a “moody” child— children with DMDD experience severe impairment that requires clinical attention. • Some of these children were previously diagnosed with bipolar disorder, even though they often did not have all the signs and symptoms. Research has also demonstrated that children with DMDD usually do not go on to have bipolar disorder in adulthood. They are more likely to develop problems with depression or anxiety.

Diagnostic Criteria for DMDD symptoms typically begin before the age of 10, but the diagnosis is not given to children under 6 or adolescents over 18. A child with DMDD experiences: – Irritable or angry mood most of the day, nearly every day – Severe temper outbursts (verbal or behavioral) at an average of three or more times per week that are out of keeping with the situation and the child’s developmental level – Trouble functioning due to irritability in more than one place (e. g. , home, school, with peers) To be diagnosed with DMDD, a child must have these symptoms steadily for 12 or more months.

Diagnostic Criteria for DMDD symptoms typically begin before the age of 10, but the diagnosis is not given to children under 6 or adolescents over 18. A child with DMDD experiences: – Irritable or angry mood most of the day, nearly every day – Severe temper outbursts (verbal or behavioral) at an average of three or more times per week that are out of keeping with the situation and the child’s developmental level – Trouble functioning due to irritability in more than one place (e. g. , home, school, with peers) To be diagnosed with DMDD, a child must have these symptoms steadily for 12 or more months.

Treatment and Prevention There is no set way to treat DMDD; however, studies have found certain treatments to be effective at lessening the outbursts and decreasing the effects. These include: • Behavior Modification Therapy • Behavioral Psychotherapy • Stimulant medication, such as Ritalin • Educating family and teachers about DMDD and how to deal with the outbursts instead of punishment • Observing the children for their individual triggers • Timeout strategies • Preventative measures, such as assigning children a safe place to alleviate their outbursts • Giving children a person they can confide in when on the verge of an outbreak • Giving children unlimited drinking fountain breaks to alleviate the tension they are experiencing • Counseling from school psychologists • Prescribing Risperidone, an antipsychotic • Classroom support • Modified time allotted for tests and homework • Addressing family dysfunction

Treatment and Prevention There is no set way to treat DMDD; however, studies have found certain treatments to be effective at lessening the outbursts and decreasing the effects. These include: • Behavior Modification Therapy • Behavioral Psychotherapy • Stimulant medication, such as Ritalin • Educating family and teachers about DMDD and how to deal with the outbursts instead of punishment • Observing the children for their individual triggers • Timeout strategies • Preventative measures, such as assigning children a safe place to alleviate their outbursts • Giving children a person they can confide in when on the verge of an outbreak • Giving children unlimited drinking fountain breaks to alleviate the tension they are experiencing • Counseling from school psychologists • Prescribing Risperidone, an antipsychotic • Classroom support • Modified time allotted for tests and homework • Addressing family dysfunction

Depression Criteria • Depressed mood, feels sad or empty, (irritability in children) by self report or observation. • Diminished interest or pleasure in most activities. • Weight gain or loss – in children failure to make expected weight gain. • Insomnia or hyper-somnia nearly every day. • Psychomotor agitation or retardation nearly every day, observable by others. • Fatigue or loss of energy. • Feelings of worthlessness or guilt (which may be delusional). • Inability to concentrate; inattentiveness. • Recurrent thoughts of death (not just fear of dying), recurrent suicidal ideation without a specific plan, or a suicide attempt or a specific plan.

Depression Criteria • Depressed mood, feels sad or empty, (irritability in children) by self report or observation. • Diminished interest or pleasure in most activities. • Weight gain or loss – in children failure to make expected weight gain. • Insomnia or hyper-somnia nearly every day. • Psychomotor agitation or retardation nearly every day, observable by others. • Fatigue or loss of energy. • Feelings of worthlessness or guilt (which may be delusional). • Inability to concentrate; inattentiveness. • Recurrent thoughts of death (not just fear of dying), recurrent suicidal ideation without a specific plan, or a suicide attempt or a specific plan.

Depression • At least 5 of 9 symptoms for a 2 week period, representing a change in previous functioning. • At least one of the symptoms must be depressed mood (irritable in children) or loss of interest or pleasure in usual activities. • The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment. • Impacts 3 -8% of children and adolescents.

Depression • At least 5 of 9 symptoms for a 2 week period, representing a change in previous functioning. • At least one of the symptoms must be depressed mood (irritable in children) or loss of interest or pleasure in usual activities. • The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment. • Impacts 3 -8% of children and adolescents.

Suicide • Fourth (4 th) leading cause of death in children aged 10 -15 years. • Third (3 rd) leading cause of death in adolescents and young adults (aged 15 -25 years). – Rates of suicide attempts are 3 times higher in females. – Rates of completed suicides are 5 times higher in males.

Suicide • Fourth (4 th) leading cause of death in children aged 10 -15 years. • Third (3 rd) leading cause of death in adolescents and young adults (aged 15 -25 years). – Rates of suicide attempts are 3 times higher in females. – Rates of completed suicides are 5 times higher in males.

Etiology of Depression • Psychosocial models • Life stressors • Organic etiologies – infections, medications, endocrine disorders, neurological disorders. • Lifetime risk of depression in children of depressed parent(s) is 15 -45%. – Pre-pubertal depression onset – 30% become bi-polar – Adolescent onset depression – 20% become bipolar

Etiology of Depression • Psychosocial models • Life stressors • Organic etiologies – infections, medications, endocrine disorders, neurological disorders. • Lifetime risk of depression in children of depressed parent(s) is 15 -45%. – Pre-pubertal depression onset – 30% become bi-polar – Adolescent onset depression – 20% become bipolar

Treatment for Depression • Cognitive Behavioral Therapy – identifying negative automatic thoughts, – recognizing distorted thinking, and – cognitive restructuring • Family therapy • Medication – Reserved for moderate to severe depression • Fluoxetine is FDA approved anti-depressant for child and adolescent depression (down to age 8) • Escitalopram is approved for treatment of depression in 12 -17 year olds.

Treatment for Depression • Cognitive Behavioral Therapy – identifying negative automatic thoughts, – recognizing distorted thinking, and – cognitive restructuring • Family therapy • Medication – Reserved for moderate to severe depression • Fluoxetine is FDA approved anti-depressant for child and adolescent depression (down to age 8) • Escitalopram is approved for treatment of depression in 12 -17 year olds.

Challenge of Child and Adolescent Mental Health Disorders • Symptoms of the disorder often worsen the disorder. • Impact development and overall skill acquisition. • Affect and symptoms are affected by family relationships and family behavior. • Early recognition and early effective treatment significantly reduce mortality and morbidity. • Sources of resilience and risk strongly influence the occurrence and course of child and adolescent mental health problems.

Challenge of Child and Adolescent Mental Health Disorders • Symptoms of the disorder often worsen the disorder. • Impact development and overall skill acquisition. • Affect and symptoms are affected by family relationships and family behavior. • Early recognition and early effective treatment significantly reduce mortality and morbidity. • Sources of resilience and risk strongly influence the occurrence and course of child and adolescent mental health problems.

Treatment • Typically multimodal treatment involving: – Effective Academic and Social Emotional Instruction – curriculum and instruction must be designed to motivate and promote success. – Behavioral Interventions – clear expectations and predictable contingencies designed to reduce problem behaviors and to facilitate student success. – Cognitive Behavioral Interventions – (e. g. , selfregulation, attributional retraining, cognitive restructuring) – Medication – (e. g. , anti-depressants, mood elevators, anti-anxiety medications, stimulant medications).

Treatment • Typically multimodal treatment involving: – Effective Academic and Social Emotional Instruction – curriculum and instruction must be designed to motivate and promote success. – Behavioral Interventions – clear expectations and predictable contingencies designed to reduce problem behaviors and to facilitate student success. – Cognitive Behavioral Interventions – (e. g. , selfregulation, attributional retraining, cognitive restructuring) – Medication – (e. g. , anti-depressants, mood elevators, anti-anxiety medications, stimulant medications).

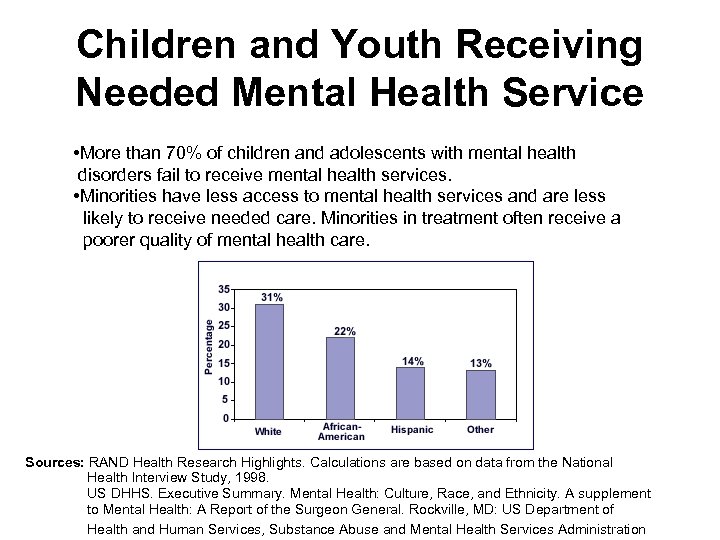

Children and Youth Receiving Needed Mental Health Service • More than 70% of children and adolescents with mental health disorders fail to receive mental health services. • Minorities have less access to mental health services and are less likely to receive needed care. Minorities in treatment often receive a poorer quality of mental health care. Sources: RAND Health Research Highlights. Calculations are based on data from the National Health Interview Study, 1998. US DHHS. Executive Summary. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity. A supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

Children and Youth Receiving Needed Mental Health Service • More than 70% of children and adolescents with mental health disorders fail to receive mental health services. • Minorities have less access to mental health services and are less likely to receive needed care. Minorities in treatment often receive a poorer quality of mental health care. Sources: RAND Health Research Highlights. Calculations are based on data from the National Health Interview Study, 1998. US DHHS. Executive Summary. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity. A supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

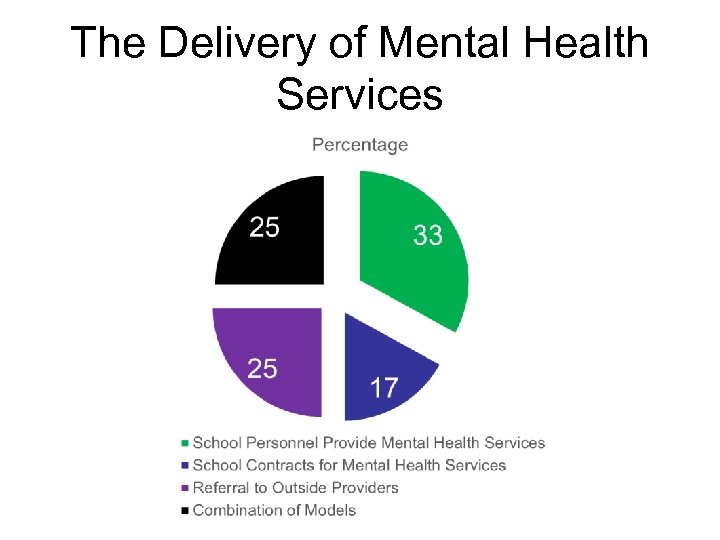

The Delivery of Mental Health Services

The Delivery of Mental Health Services

Why the School? • Achievement-focused school reform = increasing accountability for student performance, the prominence of psychosocial barriers to learning, and the gap between need and service delivery gained increased attention from the education system (Adelman & Taylor, 1998). • Catron and Weiss (1994) found that when mental health services were implemented in schools, 98% of referred students entered service, while only 17% of similar students who were referred to traditional clinic-based programs entered treatment.

Why the School? • Achievement-focused school reform = increasing accountability for student performance, the prominence of psychosocial barriers to learning, and the gap between need and service delivery gained increased attention from the education system (Adelman & Taylor, 1998). • Catron and Weiss (1994) found that when mental health services were implemented in schools, 98% of referred students entered service, while only 17% of similar students who were referred to traditional clinic-based programs entered treatment.

Building a Partnership with Community Service Providers • The goal of building partnerships with community mental health providers is held by many school districts, but often difficult to achieve due to limited resources. • One effective model employed by some school districts involves seeking policy changes from local community funding organizations (e. g. , United Way) – The United Way added a requirement that agencies seeking funding for children and youth services needed to report how they were working with their local public schools.

Building a Partnership with Community Service Providers • The goal of building partnerships with community mental health providers is held by many school districts, but often difficult to achieve due to limited resources. • One effective model employed by some school districts involves seeking policy changes from local community funding organizations (e. g. , United Way) – The United Way added a requirement that agencies seeking funding for children and youth services needed to report how they were working with their local public schools.

Effective Instructional Practices • Start with an understanding of student needs and abilities. • Promote academic success – competence. • Clear and brief rules – developmentally reasonable, understandable and enforceable. • Simple and predictable consequences – ideally instructional consequences. • Acknowledge and reinforce desired alternative behaviors – specific praise – differential reinforcement strategies. • Anticipate problems – use pre-correction • Change reinforcers over time – planful use of reinforcement schedule. Higher ratio of praise to reprimand.

Effective Instructional Practices • Start with an understanding of student needs and abilities. • Promote academic success – competence. • Clear and brief rules – developmentally reasonable, understandable and enforceable. • Simple and predictable consequences – ideally instructional consequences. • Acknowledge and reinforce desired alternative behaviors – specific praise – differential reinforcement strategies. • Anticipate problems – use pre-correction • Change reinforcers over time – planful use of reinforcement schedule. Higher ratio of praise to reprimand.

Instructional Consequences • Engagement in Short-term CBT course related to anger management for fighting. • Assignment to service learning activity with school club for truancy. • Assignment to structured play group for violation of playground rules/behavior.

Instructional Consequences • Engagement in Short-term CBT course related to anger management for fighting. • Assignment to service learning activity with school club for truancy. • Assignment to structured play group for violation of playground rules/behavior.

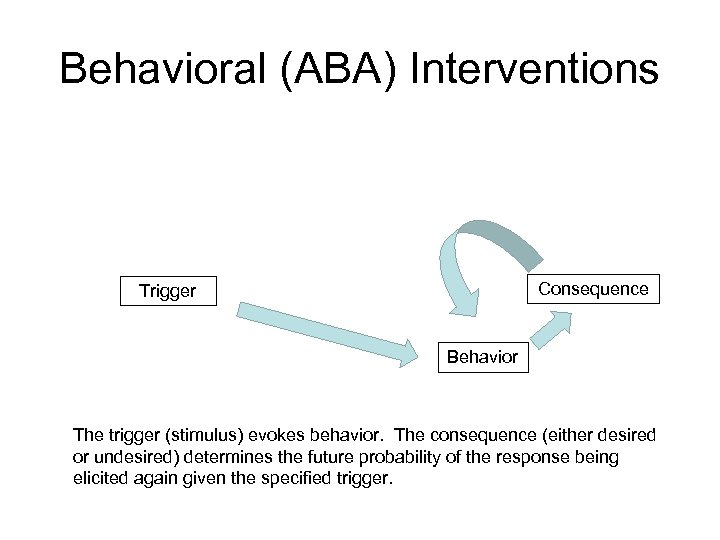

Behavioral (ABA) Interventions Consequence Trigger Behavior The trigger (stimulus) evokes behavior. The consequence (either desired or undesired) determines the future probability of the response being elicited again given the specified trigger.

Behavioral (ABA) Interventions Consequence Trigger Behavior The trigger (stimulus) evokes behavior. The consequence (either desired or undesired) determines the future probability of the response being elicited again given the specified trigger.

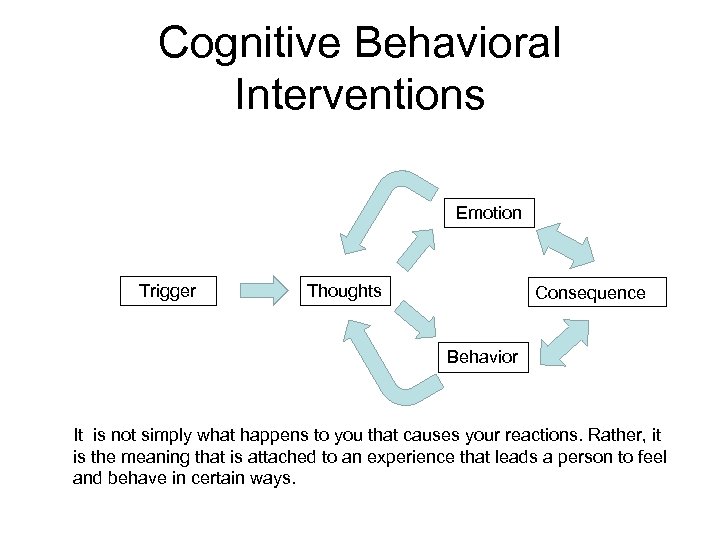

Cognitive Behavioral Interventions Emotion Trigger Thoughts Consequence Behavior It is not simply what happens to you that causes your reactions. Rather, it is the meaning that is attached to an experience that leads a person to feel and behave in certain ways.

Cognitive Behavioral Interventions Emotion Trigger Thoughts Consequence Behavior It is not simply what happens to you that causes your reactions. Rather, it is the meaning that is attached to an experience that leads a person to feel and behave in certain ways.

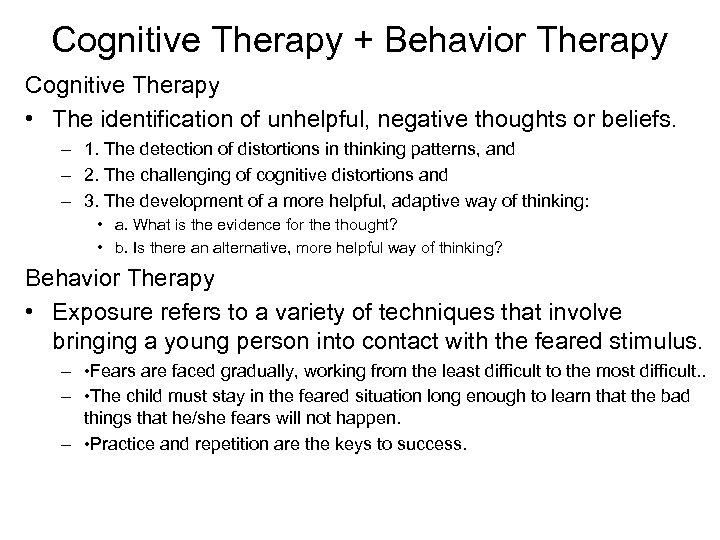

Cognitive Therapy + Behavior Therapy Cognitive Therapy • The identification of unhelpful, negative thoughts or beliefs. – 1. The detection of distortions in thinking patterns, and – 2. The challenging of cognitive distortions and – 3. The development of a more helpful, adaptive way of thinking: • a. What is the evidence for the thought? • b. Is there an alternative, more helpful way of thinking? Behavior Therapy • Exposure refers to a variety of techniques that involve bringing a young person into contact with the feared stimulus. – • Fears are faced gradually, working from the least difficult to the most difficult. . – • The child must stay in the feared situation long enough to learn that the bad things that he/she fears will not happen. – • Practice and repetition are the keys to success.

Cognitive Therapy + Behavior Therapy Cognitive Therapy • The identification of unhelpful, negative thoughts or beliefs. – 1. The detection of distortions in thinking patterns, and – 2. The challenging of cognitive distortions and – 3. The development of a more helpful, adaptive way of thinking: • a. What is the evidence for the thought? • b. Is there an alternative, more helpful way of thinking? Behavior Therapy • Exposure refers to a variety of techniques that involve bringing a young person into contact with the feared stimulus. – • Fears are faced gradually, working from the least difficult to the most difficult. . – • The child must stay in the feared situation long enough to learn that the bad things that he/she fears will not happen. – • Practice and repetition are the keys to success.

Cognitive techniques: Background • Goal: Target maladaptive thoughts 1. Negative view of themselves (e. g. , inadequate) 2. Negative view of the world (e. g. , unfair) 3. Negative view of the future (e. g. , I will always fail) • Examples of maladaptive thoughts – When things do not go the way I would like, life is awful, terrible, horrible, or catastrophic – Unhappiness is caused by uncontrollable external events – I must have sincere love and approval from all significant people in my life

Cognitive techniques: Background • Goal: Target maladaptive thoughts 1. Negative view of themselves (e. g. , inadequate) 2. Negative view of the world (e. g. , unfair) 3. Negative view of the future (e. g. , I will always fail) • Examples of maladaptive thoughts – When things do not go the way I would like, life is awful, terrible, horrible, or catastrophic – Unhappiness is caused by uncontrollable external events – I must have sincere love and approval from all significant people in my life

Self-Regulation/Self-Control • Self-monitoring – the ability to collect data or otherwise identify one’s own thoughts and behavior. • Self-evaluation – to be able to judge one’s performance accurately against some standard of performance. • Self-reinforcement – the ability to deliver self-praise or a reward contingently on the display of a specified desired behavior.

Self-Regulation/Self-Control • Self-monitoring – the ability to collect data or otherwise identify one’s own thoughts and behavior. • Self-evaluation – to be able to judge one’s performance accurately against some standard of performance. • Self-reinforcement – the ability to deliver self-praise or a reward contingently on the display of a specified desired behavior.

Stress Management • Techniques to control symptoms of emotional distress. – Relaxation Activities – Yoga – Mindfulness Programming – Exercise/Movement – Meditation – Music – Scented Candle

Stress Management • Techniques to control symptoms of emotional distress. – Relaxation Activities – Yoga – Mindfulness Programming – Exercise/Movement – Meditation – Music – Scented Candle

Promote Coping Skills/ Alternative Responses Activities that promote the acquisition of socially appropriate and healthy alternatives to dealing with stress.

Promote Coping Skills/ Alternative Responses Activities that promote the acquisition of socially appropriate and healthy alternatives to dealing with stress.

Problem- Solving Training • Problem Identification – component skills involve problem sensitivity or the ability to “sense” the presence of a problem by identifying “uncomfortable” feelings. • Alternative Thinking – the ability to generate multiple alternative solutions to a given interpersonal problem situation. • Consequential Thinking – the ability to foresee the immediate and more long-range consequences of a particular alternative and to use this information in the decision-making process. • Means-Ends Thinking – the ability to elaborate or plan a series of specific actions ( a means) to attain a given goal (ends), to recognize and devise ways around potential obstacles, and to use a realistic time framework in implementing steps towards the goal.

Problem- Solving Training • Problem Identification – component skills involve problem sensitivity or the ability to “sense” the presence of a problem by identifying “uncomfortable” feelings. • Alternative Thinking – the ability to generate multiple alternative solutions to a given interpersonal problem situation. • Consequential Thinking – the ability to foresee the immediate and more long-range consequences of a particular alternative and to use this information in the decision-making process. • Means-Ends Thinking – the ability to elaborate or plan a series of specific actions ( a means) to attain a given goal (ends), to recognize and devise ways around potential obstacles, and to use a realistic time framework in implementing steps towards the goal.

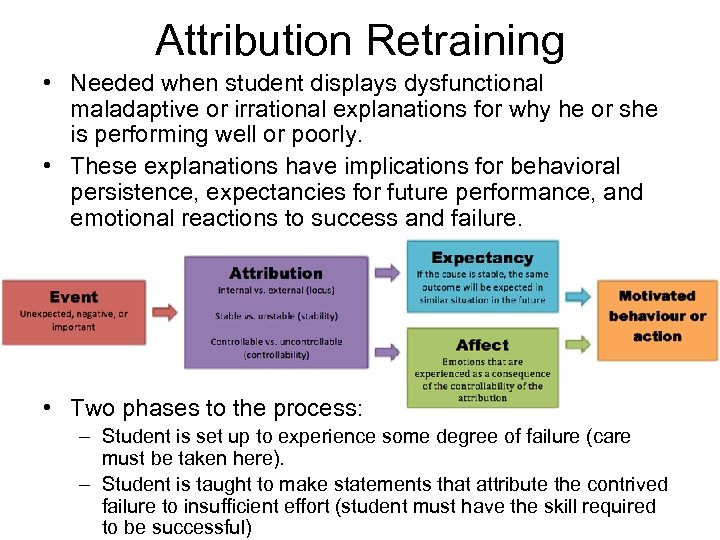

Attribution Retraining • Needed when student displays dysfunctional maladaptive or irrational explanations for why he or she is performing well or poorly. • These explanations have implications for behavioral persistence, expectancies for future performance, and emotional reactions to success and failure. • Two phases to the process: – Student is set up to experience some degree of failure (care must be taken here). – Student is taught to make statements that attribute the contrived failure to insufficient effort (student must have the skill required to be successful)

Attribution Retraining • Needed when student displays dysfunctional maladaptive or irrational explanations for why he or she is performing well or poorly. • These explanations have implications for behavioral persistence, expectancies for future performance, and emotional reactions to success and failure. • Two phases to the process: – Student is set up to experience some degree of failure (care must be taken here). – Student is taught to make statements that attribute the contrived failure to insufficient effort (student must have the skill required to be successful)

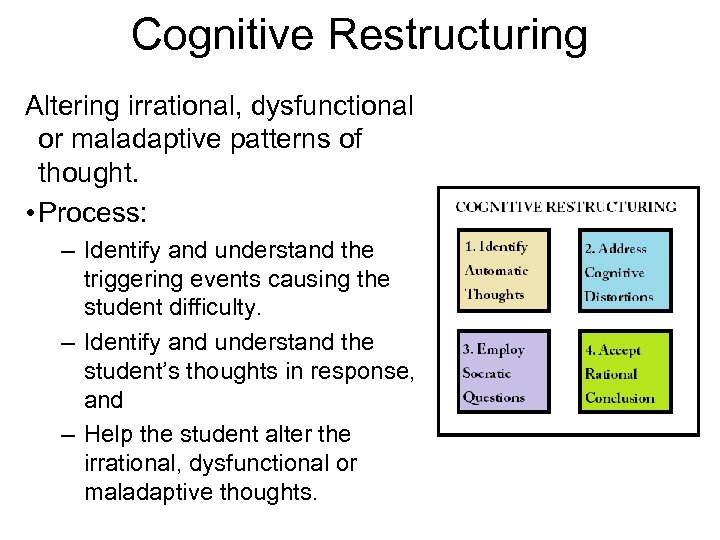

Cognitive Restructuring Altering irrational, dysfunctional or maladaptive patterns of thought. • Process: – Identify and understand the triggering events causing the student difficulty. – Identify and understand the student’s thoughts in response, and – Help the student alter the irrational, dysfunctional or maladaptive thoughts.

Cognitive Restructuring Altering irrational, dysfunctional or maladaptive patterns of thought. • Process: – Identify and understand the triggering events causing the student difficulty. – Identify and understand the student’s thoughts in response, and – Help the student alter the irrational, dysfunctional or maladaptive thoughts.

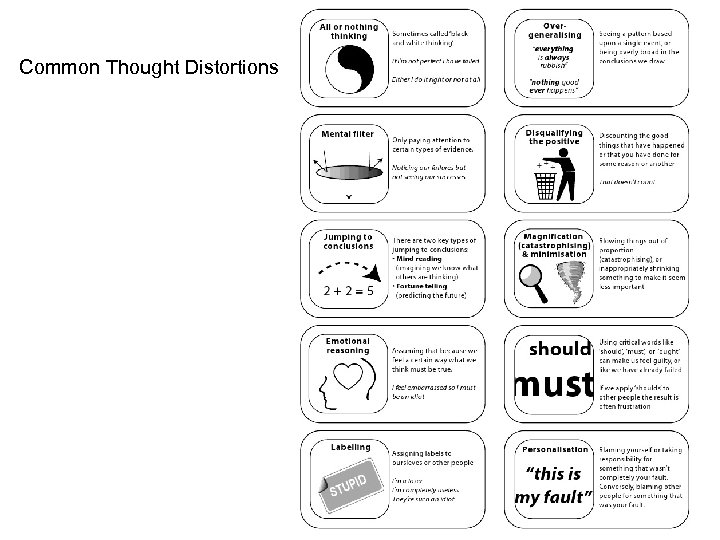

Common Thought Distortions

Common Thought Distortions

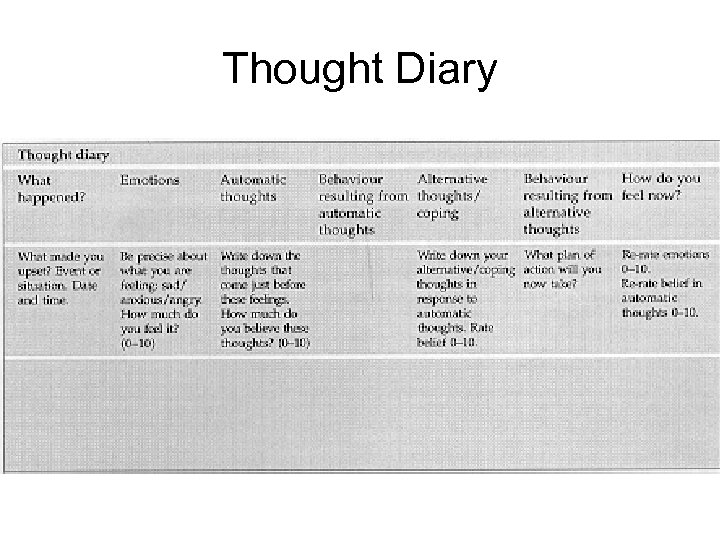

Thought Diary

Thought Diary

Self-Instruction Training (Meichenbaum & Goodman 1971) • Cognitive Modeling – the teacher performs a task • • while talking aloud; the student observes. Overt External Guidance – The student and teacher both perform the task while talking aloud together. Overt Self-Guidance – The student performs the task using the same verbalizations as the teacher (talk together). Faded Self-Guidance – The student whispers the instructions (often in an abbreviated form) while going through the task. Covert Self-Guidance – The student performs the task, guided by self-speech.

Self-Instruction Training (Meichenbaum & Goodman 1971) • Cognitive Modeling – the teacher performs a task • • while talking aloud; the student observes. Overt External Guidance – The student and teacher both perform the task while talking aloud together. Overt Self-Guidance – The student performs the task using the same verbalizations as the teacher (talk together). Faded Self-Guidance – The student whispers the instructions (often in an abbreviated form) while going through the task. Covert Self-Guidance – The student performs the task, guided by self-speech.

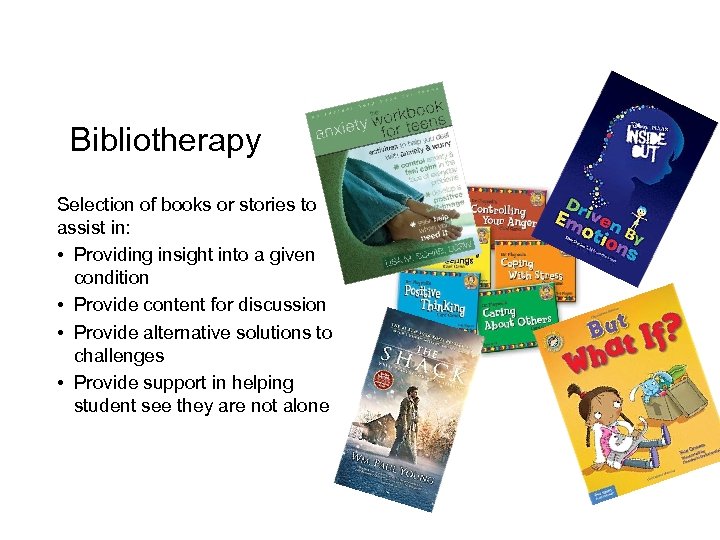

Bibliotherapy Selection of books or stories to assist in: • Providing insight into a given condition • Provide content for discussion • Provide alternative solutions to challenges • Provide support in helping student see they are not alone

Bibliotherapy Selection of books or stories to assist in: • Providing insight into a given condition • Provide content for discussion • Provide alternative solutions to challenges • Provide support in helping student see they are not alone

Behavioral Escalation • Even with the most conscientious teacher, there will be times when a student becomes upset and his or her behavior will begin to escalate towards a potential crisis.

Behavioral Escalation • Even with the most conscientious teacher, there will be times when a student becomes upset and his or her behavior will begin to escalate towards a potential crisis.

Frequently, students display behavior that appears hostile, aggressive, and defiant. We feel as if the student is attempting to control the situation. As the teacher, we feel we must exert control – “The student must learn that he is not in control. He has to respect me!” We engage in behaviors such as: • Raise our voice - reprimand • Threaten or assign aversive consequences

Frequently, students display behavior that appears hostile, aggressive, and defiant. We feel as if the student is attempting to control the situation. As the teacher, we feel we must exert control – “The student must learn that he is not in control. He has to respect me!” We engage in behaviors such as: • Raise our voice - reprimand • Threaten or assign aversive consequences

What we need to understand is that the student’s efforts to control the situation is motivated by FEAR. The student feels that these efforts at control are his only way to protect his safety. Thus, our efforts to wrestle control from the student only increases the threat he feels towards his safety. Thus, his behavior often simply escalates.

What we need to understand is that the student’s efforts to control the situation is motivated by FEAR. The student feels that these efforts at control are his only way to protect his safety. Thus, our efforts to wrestle control from the student only increases the threat he feels towards his safety. Thus, his behavior often simply escalates.

What to do? ? ?

What to do? ? ?

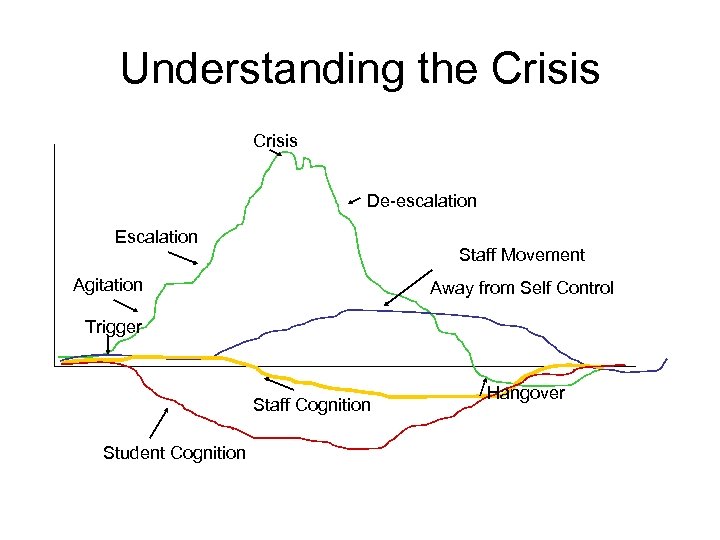

Understanding the Crisis De-escalation Escalation Staff Movement Agitation Away from Self Control Trigger Staff Cognition Student Cognition Hangover

Understanding the Crisis De-escalation Escalation Staff Movement Agitation Away from Self Control Trigger Staff Cognition Student Cognition Hangover

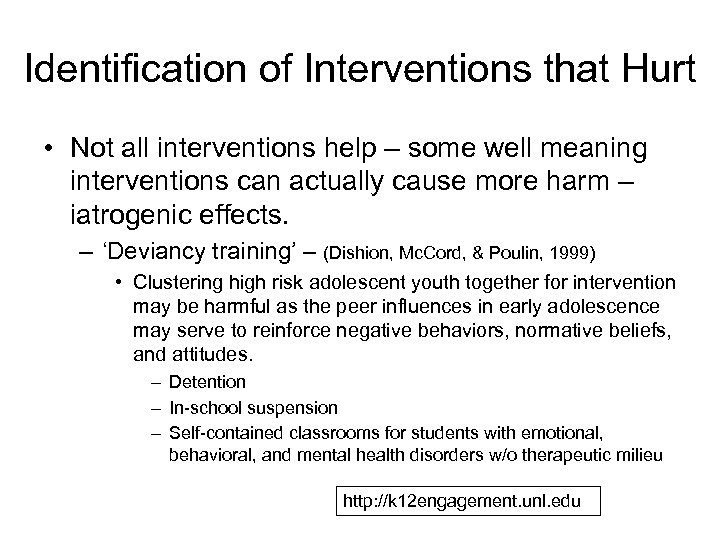

Identification of Interventions that Hurt • Not all interventions help – some well meaning interventions can actually cause more harm – iatrogenic effects. – ‘Deviancy training’ – (Dishion, Mc. Cord, & Poulin, 1999) • Clustering high risk adolescent youth together for intervention may be harmful as the peer influences in early adolescence may serve to reinforce negative behaviors, normative beliefs, and attitudes. – Detention – In-school suspension – Self-contained classrooms for students with emotional, behavioral, and mental health disorders w/o therapeutic milieu http: //k 12 engagement. unl. edu

Identification of Interventions that Hurt • Not all interventions help – some well meaning interventions can actually cause more harm – iatrogenic effects. – ‘Deviancy training’ – (Dishion, Mc. Cord, & Poulin, 1999) • Clustering high risk adolescent youth together for intervention may be harmful as the peer influences in early adolescence may serve to reinforce negative behaviors, normative beliefs, and attitudes. – Detention – In-school suspension – Self-contained classrooms for students with emotional, behavioral, and mental health disorders w/o therapeutic milieu http: //k 12 engagement. unl. edu

• Programs to Address Anger and Aggression – The Anger Coping Program http: //www. emstac. org/registered/topics/posbehavior/early/anger. htm The Anger Coping Program is a school-based intervention that focuses on developing anger management skills through group intervention. Groups of four to six students and two co-leaders from the school, one of which should be a pupil services professional, meet weekly to improve perspective taking, problem solving skills, recognition of emotions associated with anger arousal, and strategies for managing conflicts.

• Programs to Address Anger and Aggression – The Anger Coping Program http: //www. emstac. org/registered/topics/posbehavior/early/anger. htm The Anger Coping Program is a school-based intervention that focuses on developing anger management skills through group intervention. Groups of four to six students and two co-leaders from the school, one of which should be a pupil services professional, meet weekly to improve perspective taking, problem solving skills, recognition of emotions associated with anger arousal, and strategies for managing conflicts.

– Helping Schoolchildren Cope with Anger: A Cognitive-Behavioral Intervention J. Larson and J. Lochman (2002). New York: Guilford Press http: //www. researchpress. com/product/item/8488/ This book presents an empirically supported group intervention for 8 - to 12 -year-olds with anger and aggression problems. The Anger Coping Program has been demonstrated effective in reducing teacher- and parent-directed aggression and enhancing students’ classroom behavior, social competence, and academic achievement. In one volume, the authors provide a session-by-session cognitive-behavioral treatment manual, a clear rationale for the program, and instructions for implementation.

– Helping Schoolchildren Cope with Anger: A Cognitive-Behavioral Intervention J. Larson and J. Lochman (2002). New York: Guilford Press http: //www. researchpress. com/product/item/8488/ This book presents an empirically supported group intervention for 8 - to 12 -year-olds with anger and aggression problems. The Anger Coping Program has been demonstrated effective in reducing teacher- and parent-directed aggression and enhancing students’ classroom behavior, social competence, and academic achievement. In one volume, the authors provide a session-by-session cognitive-behavioral treatment manual, a clear rationale for the program, and instructions for implementation.

– Coping Cat Program for Anxious Youth (ages 8 -13) Philip C. Kendall, Ph. D. , ABPP, Temple University, & Kristina A. Hedtke, M. A. , Temple University Child and Adolescent Anxiety Disorders Clinic – http: //www. promisingpractices. net/program. asp? programid=153#progra minfo – The Coping Cat program is a cognitive-behavioral therapy intervention that helps children recognize and analyze anxious feelings and develop strategies to cope with anxiety-provoking situations. The program focuses on four related components: 1) recognizing anxious feelings and physical reactions to anxiety; 2) clarifying feelings in anxiety-provoking situations; 3) developing a coping plan (e. g. , modifying anxious self-talk into coping self-talk, or determining what coping actions might be effective); and 4) evaluating performance and administering selfreinforcement. By incorporating adaptive skills to prevent or reduce feelings of anxiety, therapist uses a workbook to guide the child through consideration of previous behavior in situations in which the child felt anxious, as well as the development of expectations for future behavior in anxious situations. The workbook is used for children aged 8 to 13 years and the CAT Project workbook is used for children aged 14 to 17 years. The CAT Project differs from Coping Cat only in the use of developmentally appropriate pictures and examples for older ages.

– Coping Cat Program for Anxious Youth (ages 8 -13) Philip C. Kendall, Ph. D. , ABPP, Temple University, & Kristina A. Hedtke, M. A. , Temple University Child and Adolescent Anxiety Disorders Clinic – http: //www. promisingpractices. net/program. asp? programid=153#progra minfo – The Coping Cat program is a cognitive-behavioral therapy intervention that helps children recognize and analyze anxious feelings and develop strategies to cope with anxiety-provoking situations. The program focuses on four related components: 1) recognizing anxious feelings and physical reactions to anxiety; 2) clarifying feelings in anxiety-provoking situations; 3) developing a coping plan (e. g. , modifying anxious self-talk into coping self-talk, or determining what coping actions might be effective); and 4) evaluating performance and administering selfreinforcement. By incorporating adaptive skills to prevent or reduce feelings of anxiety, therapist uses a workbook to guide the child through consideration of previous behavior in situations in which the child felt anxious, as well as the development of expectations for future behavior in anxious situations. The workbook is used for children aged 8 to 13 years and the CAT Project workbook is used for children aged 14 to 17 years. The CAT Project differs from Coping Cat only in the use of developmentally appropriate pictures and examples for older ages.

• Programs for Depression and Anxiety – Think Good - Feel Good: Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Workbook for Children and Young People Stallard, P. (2002). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons Think Good – Feel Good is an exciting and pioneering new practical resource in print and on the Internet for undertaking cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) with children and young people. The materials have been developed by the author and field-tested in clinical work with children and young people presenting with a range of psychological problems. Paul Stallard introduces his resource by covering the basic theory and rationale behind CBT and how the workbook should be used. An attractive and lively workbook follows which covers the core elements used in CBT programs but conveys these ideas to children and young people in an understandable way and uses real life examples familiar to them. The concepts introduced to the children can be applied to their own unique set of problems through the series of practical exercises and worksheets.

• Programs for Depression and Anxiety – Think Good - Feel Good: Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Workbook for Children and Young People Stallard, P. (2002). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons Think Good – Feel Good is an exciting and pioneering new practical resource in print and on the Internet for undertaking cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) with children and young people. The materials have been developed by the author and field-tested in clinical work with children and young people presenting with a range of psychological problems. Paul Stallard introduces his resource by covering the basic theory and rationale behind CBT and how the workbook should be used. An attractive and lively workbook follows which covers the core elements used in CBT programs but conveys these ideas to children and young people in an understandable way and uses real life examples familiar to them. The concepts introduced to the children can be applied to their own unique set of problems through the series of practical exercises and worksheets.

– Taking Action Program for Depressed Youth Kevin Stark, Ph. D. , University of Texas at Austin, Philip C. Kendall, Ph. D. , ABPP, Temple University, with Mary Mc. Carthy, Mary Stafford, Rachel Barron, and Marcus Thomeer, University of Texas at Austin. https: //www. msu. edu/course/cep/888/Depression/taking. htm Taking Action is a manual-based treatment program for children ages 9 to 13 who have unipolar depressive disorder, dysthymia, or depressed mood. Although the treatment model and procedures are appropriate for all ages of youth, the presentation method used in this program is developmentally appropriate for 9 to 13 -year-olds and would have to be altered to address the developmental needs of younger or older children.

– Taking Action Program for Depressed Youth Kevin Stark, Ph. D. , University of Texas at Austin, Philip C. Kendall, Ph. D. , ABPP, Temple University, with Mary Mc. Carthy, Mary Stafford, Rachel Barron, and Marcus Thomeer, University of Texas at Austin. https: //www. msu. edu/course/cep/888/Depression/taking. htm Taking Action is a manual-based treatment program for children ages 9 to 13 who have unipolar depressive disorder, dysthymia, or depressed mood. Although the treatment model and procedures are appropriate for all ages of youth, the presentation method used in this program is developmentally appropriate for 9 to 13 -year-olds and would have to be altered to address the developmental needs of younger or older children.

Strategies: What Works for Primary Care …is a set of principles, strategies and tools that are theory - based, evidence - driven, and systems - oriented, that can be used to improve the health and well-being of all children Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM, eds. 2008. Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents, Third Edition. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics

Strategies: What Works for Primary Care …is a set of principles, strategies and tools that are theory - based, evidence - driven, and systems - oriented, that can be used to improve the health and well-being of all children Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM, eds. 2008. Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents, Third Edition. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics

Strategies: What Works for Primary Care Strategies for System Change in Children’s Mental Health: A Chapter Action Kit Strategies to: • Partner with Families • Assess the Service Environment • Collaborate with MH Professionals • Educate Chapter Members • Partner with Child-Serving Agencies • Improve Children’s MH Financing Available at www. aap. org/mentalhealth

Strategies: What Works for Primary Care Strategies for System Change in Children’s Mental Health: A Chapter Action Kit Strategies to: • Partner with Families • Assess the Service Environment • Collaborate with MH Professionals • Educate Chapter Members • Partner with Child-Serving Agencies • Improve Children’s MH Financing Available at www. aap. org/mentalhealth